ABSTRACT

Improving health literacy is one key to buoying our nation’s troubled health care system. As system-level health literacy improvement strategies take the stage among national priorities for health care, the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model of care emerges as a compelling avenue for their widespread implementation. With a shared focus on effective communication and team-based care organized around patient needs, health literacy principles and the PCMH are well aligned. However, their synergy has received little attention, even as PCMH demonstration projects and health literacy interventions spring up nationwide. While many health literacy interventions are limited by their focus on a single point along the continuum of care, creating a “room” for health literacy within the PCMH may finally provide a multi-dimensional, system-level approach to tackling the full range of health literacy challenges. Increasing uptake coupled with federal support and financial incentives further boosts the model’s potential for advancing health literacy. On the journey toward a revitalized health care system, integrating health literacy into the PCMH presents a promising opportunity that deserves consideration.

KEY WORDS: communication, health literacy, patient-centered care, medical home

INTRODUCTION

Rehabilitating an ailing health care system is essential to our nation’s public, social, and economic health. In what some have called “the perfect storm,”1 the country’s shifting demographics, declining health literacy, and evolving economy threaten to exacerbate already dire problems related to health disparities, quality, and costs. Two issues receiving increasing attention as both challenges and opportunities are the invigorated efforts to improve health literacy2–7 and advance the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model of care.8–15 While the two have been loosely linked,16,17 the striking common threads between them have been largely ignored.

As recently noted by Rudd,6 the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy5 shifts attention from the literacy skills of individuals to the health care providers and systems that serve them and calls for system-level changes that support effective communication. DeWalt18 further emphasizes how health systems unwittingly sabotage the effectiveness of the care they provide through suboptimal communication when care is handed over to the patient. The US Surgeon General summarizes the challenge poignantly: “As clinicians, what we say does not matter unless patients are able to understand the information we give them well enough to use it to make good health-care decisions. Otherwise we didn’t reach them, and that is the same as if we didn’t treat them.”7

Enhancing clear, patient-centered communication is a widely endorsed strategy for improving health literacy,4,5,19–22 with organizations such as the Joint Commission urging health systems to “make effective communications an organizational priority” and to “address patients’ communication needs across the continuum of care.”4 We propose that the PCMH model merits consideration as a foundation for achieving both goals. Not only does the model include many features that intrinsically support patient-centered communication along the care continuum, its increasing uptake12–15 and related incentives23–25 may help address challenges that can impede efforts to prioritize effective communication.

With momentum propelling the PCMH model forward, we see a novel opportunity to integrate health literacy into a system-based model of care—and for health literacy researchers to study the impact.

PROBLEMS AND PROMISE: A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF HEALTH LITERACY AND THE PCMH

Briefly summarizing relevant aspects of health literacy and the PCMH will help illustrate the synergies between them. Among many closely related definitions of health literacy evolving from Ratzan’s and Parker’s,26 we endorse the one recently proposed by Berkman et al.27: “the degree to which individuals can obtain, process, understand, and communicate about health-related information needed to make informed health decisions.” Regardless of definition, the key point is that at least half of American adults may not understand the overly complex information inherent in medical care, causing wide-ranging negative consequences affecting care quality, disparities, and costs.2,3,28

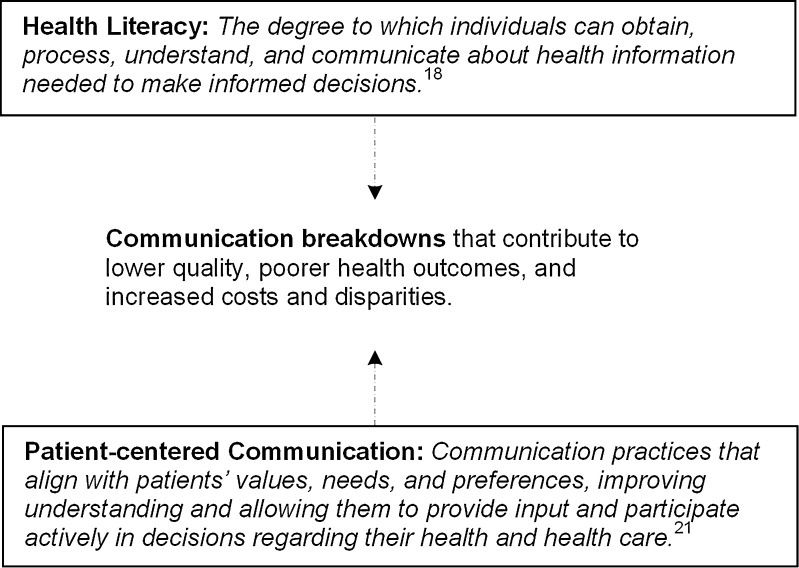

Evidence from Wynia et al.20 suggests that using patient-centered communication can help mitigate the effects of limited health literacy. As defined by Epstein et al.,29 patient-centered communication “aligns with patients’ values, needs, and preferences, improving understanding and allowing them to provide input and participate actively in decisions regarding their health and health care.” However, a large gap exists between patients’ health literacy and the degree to which most health systems and practices use patient-centered communication20—creating communication breakdowns that contribute to the negative consequence mentioned above (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Gap between patient’s health literacy and health systems’ use of patient-centered communication.

Like health literacy, the PCMH has many closely related definitions—but few are succinct. At its most basic, the PCMH is simply good primary care enhanced by health information technology (IT) capabilities and innovative payment models.11,30 Joint principles of the model31 emerged separately from policy work at the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians, and were soon endorsed by other primary care professional organizations and the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative.32 The principles include improved access, ongoing patient-provider relationships, whole-person orientation, team-based approaches to care, coordination and integration supported by health IT, enhanced quality and safety, and payment for added value.

A PCMH checklist33 further distills the model’s features into four categories: quality, health IT, practice organization, and patient experience. Later in our discussion, we focus on the checklist’s patient experience elements: clear communication, improved access, shared decision making, and self-management support.

A SYNERGISTIC APPROACH TO COST, QUALITY, AND DISPARITIES

Evidence from successful PCMH demonstration projects12,14 and effective health literacy interventions34,35 suggests a collective potential to curb costs, boost quality, and provide more equitable care—essential priorities if we are to weather the coming storm. Interestingly, the PCMH demonstrations and health literacy interventions found to be most effective often share core features and produce similar outcomes.

For example, experiences in several peer-reviewed PCMH demonstrations36–40 strongly suggest a potential to curb costs—with the savings stemming primarily from decreases in emergency department (ED) utilization and hospitalization, especially for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Similarly, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)’s recently updated review35 of health literacy interventions and outcomes concluded that multi-dimensional interventions focusing on self-management and treatment adherence—two PCMH focal points—led to significant reductions in hospital and ED use.

Many other peer-reviewed PCMH demontrations36,37,41–44 have also shown significant health-outcome-related improvements, such as better managed diabetes, asthma, and blood pressure. Among the health literacy interventions AHRQ reviewed, those that demonstrated the potential to effectively improve health outcomes were again focused on self-management and treatment adherence.35 A closer look at the few “effective” health literacy interventions highlighted in the report reveals three randomized controlled trials45–47 that tested strategies particularly well-suited for implementation within a PCMH: individualized communication, scheduled phone follow-up, and team-based care, among others (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effective Health Literacy Interventions Well-suited for Implementation in a PCMH

| Authors | Intervention description | Key findings and insights |

|---|---|---|

| Rothman RL, DeWalt DA, Malone RM, et al. 45 | Primary-care based diabetes disease management program featuring individualized communication delivered to improve understanding among low-literacy patients | Among low-literacy patients, those in the intervention were more likely than controls to achieve target blood sugar levels. This suggests that programs addressing literacy can help improve outcomes for low-literacy patients and that increasing access to such programs could help reduce health disparities |

| DeWalt DA, Malone RM, Brant ME, et al. 46 | Primary-care-based heart failure self-management program emphasizing daily monitoring, dose self-adjustment, and symptom recognition. Other features include picture-based education materials and scheduled phone follow-up | Patients who received the intervention had a lower rate of hospitalization or death than controls. The difference was larger for low-literacy patients than for high-literacy patients. Patients with low literacy and other vulnerable populations are likely to benefit most from such programs |

| Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. 47 | A pharmacist-led intervention for outpatients with heart failure featuring patient-centered verbal instructions and clear written instructions that made use of icons and an easy-to-follow timeline. The pharmacist worked with a multi-disciplinary team | Compared with controls, patients in the intervention group had fewer emergency department visits and hospitalizations, as well as lower annual direct health care costs. Medication adherence was higher in the intervention group, but this difference dissipated somewhat during follow-up, suggesting a need for continued intervention |

Authors of the AHRQ report also observed emerging evidence that low health literacy mediates racial disparities in care,48 which suggests that improving health literacy may be a worthwhile strategy for helping overcome disparities. Other findings also support the notion that health systems can promote health equity by addressing health literacy17,45,49–51 and providing patient-centered care.17,52

THERE’S A “ROOM” FOR HEALTH LITERACY IN THE MEDICAL HOME

While health literacy interventions have become increasingly widespread, relatively few high-quality studies have produced significantly positive results.34,35 One key challenge is that health literacy spans multiple domains along the continuum of care: Patients must understand health information (verbal, print, and web-based), navigate health services, make treatment decisions, and participate in self care. However, half the interventions in AHRQ’s updated review addressed just a single domain, for example improving understanding by making information more readable or supplementing it with alternative media.35

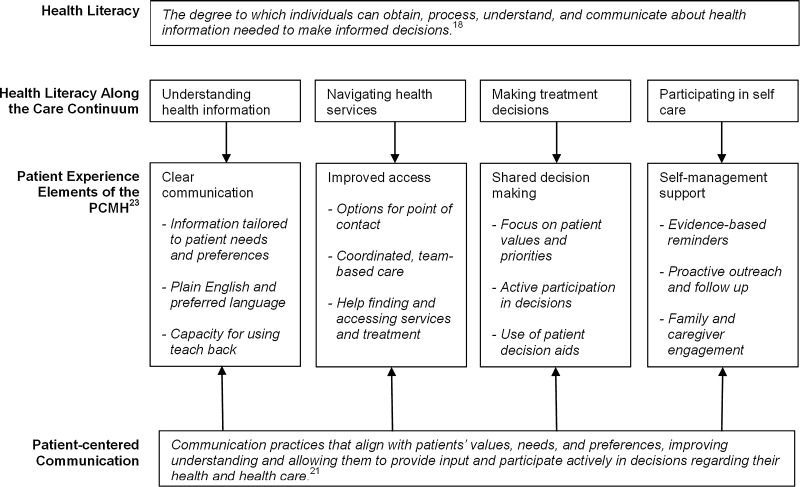

We propose that a comprehensive model of care like the PCMH can potentially address the multi-dimensional nature of the health literacy problem. In fact, the patient experience elements from the PCMH checklist (clear communication, improved access, shared decision making, and self-management) align remarkably well with health literacy challenges along the care continuum (understanding, navigation, decision making, and self-care)—an alignment that could potentially bridge the gap between patients’ health literacy and health systems’ communication practices (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The PCMH as a bridge between patients’ health literacy and health systems’ use of patient-centered communication.

A composite of PCMH attributes derived from the joint principles31 and checklist,33 and exemplified in successful demonstration projects across the country12,14,15 helps further illustrate how the model is well suited to comprehensively address health literacy challenges.

Understanding health information. A central feature of the PCMH is clear communication stemming from a robust and ongoing patient-provider relationship.31,33 Patients are viewed through a whole-person approach,31 enabling their care team to understand their needs and preferences around verbal, print, and electronic information.53 In addition, providing health information in plain English or in the patient’s preferred language is expected.33 The model’s team-based approach to care12,31,36,37,41 also facilitates using teach-back to confirm patient comprehension—as do longer appointment times (30 min instead of the typical 12-15) sometimes offered.36,41,53

Navigating health services. The PCMH improves access by providing patients with same-day appointments15,33 and options for point of contact: phone, online, or in person.14,33 Supplemental e-mail- and phone-based communication means questions and bi-directional information exchanges can occur easily outside typical in-person visits,53,54 which may encourage clarification of post-visit gaps in understanding. Ongoing care is coordinated by a cohesive team that helps patients find and access needed health services.14,37

Making treatment decisions. Shared-decision making is a core feature of the PCMH’s patient experience and quality ideals.31,33 Providers solicit and consider patient values and priorities, involving them as active participants in treatment decisions. Patient decision aids can be used to provide clear, evidence-based information—which has been shown to help adults with limited health literacy boost their knowledge and understanding of treatment options and outcomes.55–58 Patient decision aids are becoming more widely available, and federal agencies such as the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are building decision aid clearinghouses.59

Participating in self care. The PCMH uses features of the Chronic Care Model,60 such as evidence-based reminders and proactive outreach and follow-up, to address self-management support.12,14,33 This can help mitigate health literacy challenges or other communication breakdowns that might otherwise hinder successful self care or treatment adherence. Importantly, mobile phone-based care management and health applications may present a promising method for reaching disadvantaged or otherwise marginalized populations,61–63 especially considering rapid increases in cell phone use across racial, ethnic, educational, and economic lines.64 PCMHs also emphasize family and caregiver engagement,31,33 enhancing social supports that many patients rely on to boost their self efficacy—especially those with limited health literacy.

HOW THE PCMH ADDRESSES CHALLENGES TO SYSTEMATIC COMMUNICATION IMPROVEMENT

Addressing health literacy through system-based communication-improvement strategies is not a new idea, 4,5,19–22 and tools for assessing and improving communication practices are available (Table 2). However, implementing these tools can be challenging because of time and financial constraints that hinder stand-alone efforts to address health literacy. Because of these constraints and the vast range of competing priorities most organizations face, implementing a communication improvement initiative simply may not make the cut. This is especially true when so few payment models support communication improvement activities.

Table 2.

Tools for Assessing and Improving Communication Practices

| Tool | Description | Available at |

|---|---|---|

| The Communication Climate Assessment Toolkit (C-CAT) | The C-CAT was designed to help organizations improve communication with all patient populations by addressing culture, language, and health literacy gaps | http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/the-ethical-force-program/patient-centered-communication/organizational-assessment-resources.page? |

| Accessed November 29, 2011 | ||

| Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities | An assessment tool examining organizational efforts to enhance health literacy and providing insight into areas that need attention. It is accompanied by a resource list and suggestions for areas of improvement | Downloadable pdf files at http://ahip.org/HealthLiteracy/ |

| Accessed November 29, 2011 | ||

| Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit19 | A toolkit that assesses primary care practices for health literacy considerations, raising staff awareness and indicating specific areas to work on. It is designed to help practices ensure that systems are in place to promote better understanding by all patients | http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/literacy/ |

| Accessed November 29, 2011 | ||

| Health Literacy: A Toolkit for Communicators | A toolkit outlining five fundamental steps to take when starting up a health literacy program, plain language initiative, or member-experience program. Links to dozens of resources and tools for making the business case are provided | http://www.ahip.org/healthliteracy/toolkit |

| Accessed November 29, 2011 | ||

| Toolkit for Starting Plain Language in Your Organization | A 10-step approach to help plain language project managers navigate managerial obstacles | http://centerforplainlanguage.org/toolkit/ |

| Accessed November 29, 2011 | ||

| Unified Health Communication: Addressing Health Literacy, Cultural Competency, and Limited English Proficiency | A free, go-at-your-own-pace training to help health care professionals and students improve patient-provider communication. CME credit is available | http://www.hrsa.gov/publichealth/healthliteracy/index.html |

| Accessed November 29, 2011 |

Explicitly embedding health literacy into the PCMH would create a unique opportunity to incentivize and streamline communication improvement efforts. First, the cost savings experienced in various PCMH demonstrations12,14,36,37 are likely to appeal to the nation’s many cash-strapped practices and health systems. Boosted by federal funds supporting PCMH expansion allocated in health reform legislation,25 Medicare and Medicaid are also implementing a variety of financial incentives for practices that implement the model.23,24 As part of the PCMH, addressing health literacy appears not as an added cost, but as an integral part of a model proven to conserve precious resources.

Second, growing enthusiasm for the PCMH means health literacy can be made part of a comprehensive model of care that diverse systems and practices are voluntarily moving toward53—or being required to adopt. Notably, federal agencies have been charged with helping all 1,300 federally qualified health centers become PCMHs, and collaborations such as the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative65 are spreading the model to communities in need nationwide. With health literacy embedded in the PCMH, addressing it becomes an integral part of work that may already be planned or undertaken, rather than another stand-alone priority that may not make the cut.

Finally, as diverse stakeholders refine the PCMH, “natural experiments” will provide essential evidence about which features work best to improve outcomes.66 Additionally, guidance and coaching programs are rapidly being developed to support PCMH transformations—signaling a critical time for solidifying health literacy as an explicit component of the model.

INTEGRATING HEALTH LITERACY INTO THE PCMH: SHORING UP OUR FOUNDATION

With the perfect storm approaching, now is the time to consider how integrating health literacy into the PCMH can shore up the foundation of a renovated health care system. Single solutions, such as using teach-back or providing information at a 6th-grade reading level, will not be sufficient. In addition to societal and educational innovations, communication improvements across America’s health systems are crucial.

Integrating health literacy principles into the PCMH is a promising strategy for systematically implementing these improvements. The model’s promise stems from features that address health literacy challenges across the continuum of care, increasing uptake that includes safety net clinics and community settings, incentives that help organizations prioritize communication improvement, and team-based solutions that better connect practitioners with each other and the patients they serve.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Katie Coleman for sharing expertise and insights related to the patient-centered medical home. Support for the development of this manuscript comes from Group Health Research Institute.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parker RM, Wolf MS, Kirsch I. Preparing for an epidemic of limited health literacy: Weathering the perfect storm. J Gen Int Med. 2008;23(8):1273–1276. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0621-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.“What Did the Doctor Say?:” Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy-Knoll L. Low Health Literacy Puts Patients at Risk: The Joint Commission Proposes Solutions to National Problem. J Nurs Care Qual. 2007;22(3):205–209. doi: 10.1097/01.NCQ.0000277775.89652.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 2010. http://www.health.gov/communication/HLActionPlan. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 6.Rudd R. Improving Americans’ health literacy. N Engl J Med. 2010;36:2283–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1008755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin RM. Surgeon General’s perspectives for improving health by improving health literacy. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(6):784–788. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Physicians. The Advanced Medical Home: A Patient-Centered, Physician-Guided Model of Health Care. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2006: Policy Monograph. http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/policy/adv_med.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 9.Berenson RA, Hammons T, Gans David N, et al. A house is not a home: Keeping patients at the center of practice redesign. Health Aff. 2008;27(5):1219–1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). AAFP News Now Special Report: PCMH Offers Faster, Easier Access to Improved Clinical Care. http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/publications/news/news-now/pcmh/20090217pcmh-clinical.html. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 11.Larson EB, Reid R. The patient-centered medical home movement: why now? JAMA. 2010;303(16):1644–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grumback K, Grundy P. Outcomes of Implementing Patient Centered Medical Home Interventions: A Review of the Evidence from Prospective Evaluation Studies in the United States. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. http://www.pcpcc.net/files/evidence_outcomes_in_pcmh.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 13.Bitton A, Martin C, Landon BE. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. J Gen Int Med. 2010;25(6):584–592. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fields D, Leshen E, Patel K. Driving quality gains and cost savings through adoption of medical homes. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):819–826. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart EE, Jaen CR. Transforming physician practices to patient-centered medical homes: Lessons from the National Demonstration Project. Health Aff. 2011;30(3):439–445. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bechtel C, Ness DL. If you build it, will they come? Designing truly patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):914–920. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toward Health Equity and Patient-Centeredness: Integrating Health Literacy, Health Disparities, Disparities Reduction, and Quality Improvement: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeWalt DA. Ensuring safe and effective use of medication and health care. JAMA. 2010;304(23):2641–2642. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeWalt DA, Callahan LF, Hawk VH, et al. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. (Prepared by North Carolina Network Consortium, The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, under Contract No. HHSA290200710014.) AHRQ Publication No. 10-0046-EF. Rockville, MD. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2010.

- 20.Wynia MK, Osborn CY. Health literacy and communication quality in health care organizations. J Health Comm. 2010;15:102–115. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stableford S, Mettger W. Plain language: a strategic response to the health literacy challenge. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28(1):71–93. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paasche-Orlow MK, Schillinger D, Greene SM, Wagner EH. How health care systems can begin to address the challenge of limited literacy. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(8):884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Fact Sheet. http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=3872&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=0&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=6&intPage=&showAll=1&pYear=1&year=2010&desc=&cboOrder=date. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 24.Multi-payer Advanced Primary Care Practice (MAPCP) Demonstration Fact Sheet.http://www.cms.gov/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/mapcpdemo_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 25.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Section 3502: Establishing community health teams to support the patient-centered medical home. 2010. http://docs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 26.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, eds. National Library of Medicine current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive//20061214/pubs/cbm/hliteracy.html. Accessed November 29, 2011. Vol. NLM Pub. No. CMB 2000-1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- 27.Berkman ND, Davis TC, McCormack L. Health literacy: What is it? J Health Comm. 2010;15:9–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vernon JA, Trujillo A, Rosenbaum S, DeBuono B. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stange KC, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, Jaen CR. Context for Understanding the National Demonstration Project and the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. February 2007. http://www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/policy/fed/jointprinciplespcmh0207.Par.0001.File.tmp/022107medicalhome.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 32.Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. http://www.pcpcc.net/content/patient-centered-medical-home. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 33.American Academy of Family Physicians. Patient-Centered Medical Home Checklist. http://www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/membership/pcmh/checklist.Par.0001.File.tmp/PCMHChecklist.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 34.Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Sheridan S, Berkman N, Lohr KN. Interventions to improve health outcomes for patients with low literacy. A systematic review. J Gen Int Med. 2005;20(2):185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 199. (Prepared by RTI International—University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10056-I.) AHRQ Publication No.11-E006. Rockville, MD. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2011.

- 36.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The Group Health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):835–843. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilfillan RJ, Tomcavage J, Rosenthal MD, et al. Value and the medical home: effects of transformed primary care. Am J Managed Care. 2010;16(8):607–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dorr DA, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, et al. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2195–2202. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leff B, Reider L, Frick K, et al. Guided care and the cost of complex health care: a preliminary report. Am J Managed Care. 2009;15(8):555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal TC, Horwitz ME, Snyder G, O’Conner J. Medicaid primary care services in New York State: Partial capitation vs. full capitation. J Fam Prac. 1996;42(4):362–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid RJ, Fishman PA, Yu O, et al. A patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Managed Care. 2009;15(9):e71–e87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE, et al. Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Resp Critical Care Med. 2010;182(7):890–896. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1579OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Counsel SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;12;298(22):2623-2633 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Steiner BD, Denham AC, Ashkin E, Newton WP, Wroth T, Dobson LA. Community care of North Carolina: Improving care through community health networks. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):361–367. doi: 10.1370/afm.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothman RL, DeWalt DA, Malone R. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary care-based diabetes disease management program. JAMA. 2204;292(14):1711-1715. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.DeWalt DA, Malone RM, Bryant ME, et al. A heart failure self-management program for patients of all literacy levels: A randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN11535170] BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):714–725. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):754–762. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parker RM, Ratzan SC, Lurie N. Health literacy: A policy challenge for advancing high-quality health care. Health Aff. 2003;22(4):147–153. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.4.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patient Centered Medical Home Debuts. New England Journal of Medicine CareerCenter. Available at: http://www.nejmcareercenter.org/article/3191/patient-centered-medical-home-debuts/. Accessed December 6, 2011.

- 54.Ralston JD, Coleman K, Reid RJ, Handley MR, Larson EB. Patient experience should be part of meaningful-use criteria. Health Aff. 2010;29(4):607–613. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson J, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery K. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jibaia-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Granchi TS, et al. Entertainment education for breast cancer surgery decisions: A randomized trial among patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(1):41-8. Epub 2010 Jul 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Volk RJ, Jibaia-Weiss ML, Hawley ST, et al. Entertainment education for prostate cancer screening: a randomised trial among patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):482-9. Epub 2008 Aug 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Volandes AE, Barry MJ, Chang Y, Paasche-Orlow MK. Improving decision making at the end of life with video images. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(1):29-34. Epub 2009 Aug 12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, et al. Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff. 2007;26(3):716–725. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. doi: 10.2307/3350391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.JC, Schatz BR. Feasibility of Mobile Phone-Based Management of Chronic Illness. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:757–761. Published online 2010 November 13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3041419/?tool=pubmed. Accessed November 29, 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Blake H. Mobile phone technology in chronic disease management. Nursing Stand. 2008;23(12):43–46. doi: 10.7748/ns2008.11.23.12.43.c6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harris LT, Tufano J, Le T, et al. Designing mobile support for glycemic control in patients with diabetes. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(5 Suppl):S37–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DRA Staff. Cell Phones and Reducing Health Disparities. Alexandria, VA: Institute for Alternative Futures, Disparity Reducing Advances Project; 2006 Sept. Report No.: 06-02. Contract No.: NO1-CO-12400 and GS-10 F-0322R. Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- 65.The Safety Net Medical Home Initiative. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Resources/2010/The-Safety-Net-Medical-Home-Initiative.aspx. Accessed November 29, 2011.

- 66.Jackson JL. The patient-centered medical home and our future health-care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):483. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1305-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]