Abstract

Introduction

The sagittal profile of conventionally and surgically treated scoliotic spines is usually analyzed via lateral views of whole-spine X-rays in an upright position. Due to a more hypokyphotic configuration of scoliotic spines, the view onto the upper thoracic vertebrae is often difficult. We investigated whether additional supine MRI measurement supports valid kyphosis angle measurement.

Patients and methods

Twenty patients with either short (n = 10, Halm-Zielke, VDS) or long spondylodesis (n = 10, dorsoventral) were assessed 5 years after surgery with standing radiographs and supine whole-spine MRI.

Results

Up to 90% of the upper thoracic vertebrae were invisible on radiographs, whereas MRI allowed visibility of almost many vertebrae. No significant difference in thoracal kyphosis angles could be observed in the comparison of X-ray and MRI data.

Conclusion

Thoracal kyphosis measurement of postoperative spines in MRI is a valid diagnostic tool with reliability comparable to that of X-ray. These results cannot be transferred to lumbar lordosis measurement and transferred only partly to coronal COBB angle measurement.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00586-011-2115-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Sagittal profile, Scoliosis, Spondylodesis, MRI, X-ray

Introduction

The reconstruction of sagittal balance is a major issue for successful long-term outcome in spinal surgery. Especially in posterior scoliosis surgery, pedicle-screw-based systems offer the possibility of achieving 3D correction (kyphosis, coronal alignment and derotation). However, the lateral-view radiologic assessment of the upper thoracic spine is flawed by major difficulties. Vertebrae are obscured by the overlying lung and scapula. Thoracic hypokyphosis or even lordosis—as it can be found in many scoliosis cases—intensifies the problem. Modulation of X-ray parameters and positioning of the patient give only insufficient solutions as active spine surgeons might have experienced intraoperatively, using the image intensifier.

The question arises, if sagittal MRI sequences could be used to obtain this information. The major drawback of the MRI method for the assessment of spinal alignment is the supine position of the patient (currently, upright MRI is not available for most patients) which potentially leads to lower angle measurements compared to standing X-ray. This problem was addressed by several authors and proven to be true for the coronal COBB angle measurements [1, 2]. For the sagittal alignment, there already is a study showing the usability of MRI information for the assessment of thoracic kyphosis angles [3]. However, there is no study comparing the standard standing X-ray procedure with MRI, neither in lying nor in upright position.

Given the fact, that the thoracic spine together with the rib cage and sternum is an anatomic unit, we hypothesize that thoracic kyphosis is not as sensitive to patient position as the cervical and lumbar region. Eventually, measurement of kyphosis angle could therefore be made from MRI more easily and more precisely compared to the conventional standing X-ray technique. The scope of our study was an intermodality comparison of standing X-ray and supine MRI in terms of coronal and sagittal COBB angle validity and the visibility of bony measurement landmarks.

For MRI we focused on the usage of the isotrope SPACE sequence, which is qualified for the evaluation of smaller structures, e.g. neuroforamina and enables a multiplanar reconstruction. Thus, multiple acquisitions in different levels become redundant, contributing to shorter scanning times.

We focused on the postoperative situation in adults, at least 5 years after scoliosis surgery as those patients offer more aspects to study (partial stiffness and many facets of vision impairment by the implanted metal) compared to native scoliotic spines.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study was approved by the institutional review board (# EK 144062008). Each participating patient gave a written consent. Inclusion criteria were: at least 5 years after ventral derotating spondylodesis (VDS) or dorsoventral spondylodesis. Each group consisted of 10 randomly selected patients (“VDS”: 8 females, 2 males; mean age at follow-up 24.8 years; mean 7.7 years after the procedure; “dorsoventral”: 7 females, 3 males; mean age at follow-up 23.4 years; mean 8 years after the procedure).

Imaging

MRI was performed with a 1.5 T scanner (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Medicals Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Spine images were acquired using a 24-element spine matrix coil. As the field-of-view (FOV) of the scanner has a maximum length of 50 cm, a three-step protocol was used to cover the whole spine, with the table moving between acquisitions in order to place either the cervical, the thoracic or the lumbar spine at the isocenter of the magnet. The examination included T1 and T2 weighted turbo spin-echo (TSE) images in sagittal orientation, and T2 weighted isotropic SPACE datasets in sagittal orientation. SPACE (sampling perfection with application optimized contrast using different flip angle evolution) is a fast spin-echo technique which allows the acquisition of high-resolution isotropic datasets in relatively short time. Parallel imaging (iPAT) with an acceleration factor of 3 was used to shorten acquisition time for the SPACE sequence.

Total imaging time was 43 min. Sequence parameters are summarized in the supplemental Table 3.

Using the postprocessing package of the Siemens Syngo 15 software, the multistation data were also displayed and stored as whole-spine images. For conventional T2 TSE and T1 TSE images this was only possible in the sagittal plane, while for the SPACE datasets, additional coronal reformats with the original slice thickness (1 mm) were also created.

Three (SZ, SW, SH) independent spine surgery fellowship-trained observers took part in the study. Each was given tables with the patient names for each imaging modality at different time points. Examiners were not allowed to make additional notes, in order to achieve a certain amount of blinding. The tables included a definition of the coronal COBB end vertebrae for each case for the thoracic and the lumbar curves. The investigators had to measure kyphosis/lordosis angles between Th2,3,4,5, 10,11,12, L1 and S1 and had to grade the visibility of vertebral landmarks (0 = not visible, measurement not possible or high degree of uncertainty; 1 = poor visibility, but measurable with some uncertainty; 2 = good visibility).

To familiarize the examiners with the computer software, each underwent an initial training period. This training period consisted of measuring each of the parameters for two other cases not included in the actual study cohort. These data were not used for statistical analysis. Measurements were made on the digitally stored radiographs/MR sequences on a 19-inch thin film transistor (TFT) liquid crystal display (LCD) monitor using the measurement tools of the IMPAX software (IMPAX EE R20 VII P1, Agfa Inc.). The final measures were directly inserted in the appropriate fields in the provided tables. The software allowed the examiner to provisionally mark the appropriate anatomical landmarks (e.g., corners of vertebral bodies) and end plates of the superior and inferior vertebrae. In case of MR sequences, the midsagittal position for each vertebra was addressed. After these lines were drawn, the software automatically generated and displayed the angles formed by these lines.

Statistical analysis

As there are no comparative studies for postoperative scoliosis patients, case number considerations were done according to the literature (MRI, CT and X-ray comparison of thoracolumbar fractures [3]).

SPSS (Version 17.0, SPSS Inc.) statistical program was used. Values are given as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons employ ANOVA test for paired data and linear regression. p values below 0.05 were considered to be significant.

To obtain interobserver reliability measures, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was determined by Cronbach’s alpha, using an ANOVA-type two-way random effects model. Results are given as the average ICC. Intraobserver reliability (observer duplicates) was not obtained, because its impact on the overall clinical reliability was expected to be inferior to the effect measured by the ICC. As a convention for sagittal interpretation, negative angles were judged as lordosis, positive angles were described as kyphosis.

Results

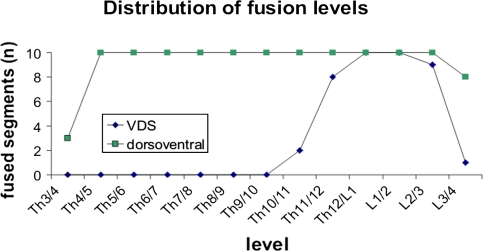

Whereas in the VDS group, the segments from Th3 through Th10 remained unfused, all dorsoventrally operated spines had a solid fusion from Th4 through L3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of fusion levels in the analyzed patient groups “VDS” and “dorsoventral”. n = number of patients with fusion at the indicated level

Good radiographic visibility of vertebral structures for the purpose of exact angle measurement was only possible in up to 15% in the upper thoracic region from Th2 to Th4. About 50–90% percent of measurements were rated “poor” in this region. In the region from Th5 to L1 good to average visibility ranged from about 50 to 85%.

MRI yielded good visibility in about 70–100% in all segments, the upper thoracic segments being the best with 98–100% (Table 1; Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Investigator-rated visibility of vertebra in X-ray and MRI

| Vertebra | Vertebra visibility (percent) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | MRI | |||||

| Good | Average | Poor | Good | Average | Poor | |

| Th2 | 3 | 8 | 89 | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Th3 | 2 | 15 | 83 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Th4 | 15 | 32 | 53 | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Th5 | 27 | 38 | 35 | 97 | 3 | 0 |

| Th11 | 38 | 48 | 14 | 80 | 17 | 3 |

| Th12 | 28 | 43 | 29 | 78 | 18 | 4 |

| L1 | 23 | 52 | 25 | 72 | 25 | 3 |

| S1 | 12 | 37 | 51 | 88 | 3 | 9 |

Each vertebra was rated in 20 patients by 3 investigators

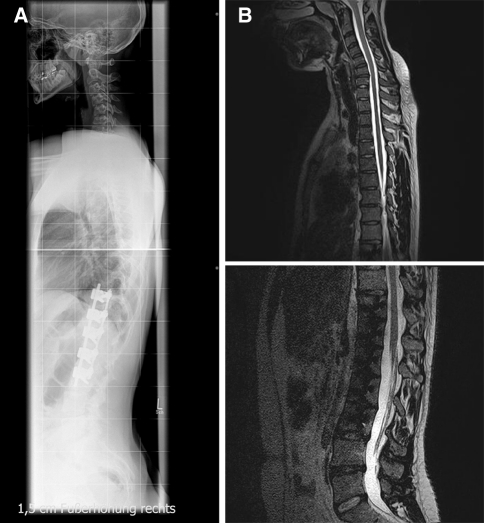

Fig. 4.

Example of a hypokyphotic scoliotic spine. a X-ray with obscured vertebrae. b Vertebrae clearly visible in MRI. Visibility of the instrumented lumbar vertebrae is possible, despite of metal artefacts

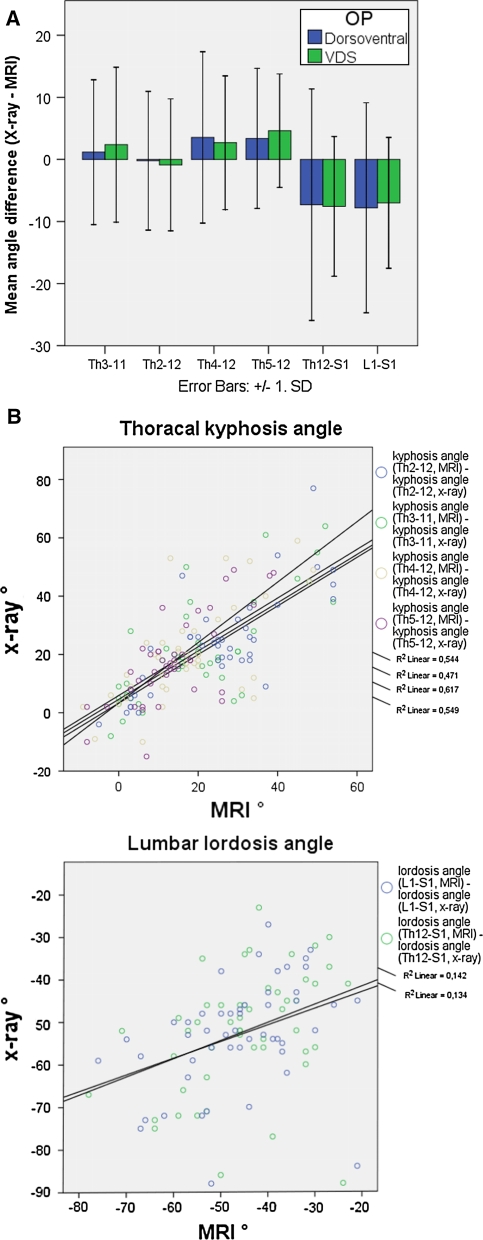

Due to the impaired visibility of the upper thoracic region, 15–25% of the kyphosis angles could not be measured in X-ray images, whereas no such problems occurred in MRI. S1 could not be seen in one case in MRI, because the image ended with L5. Kyphosis angles did not show intermodality difference between X-ray and MRI, neither in the VDS nor in the dorsoventral group. However, in standing position (X-ray) lordosis angles were significantly lower (more negative = more lordosis) than in supine position (MRI) in the lumbar region (p < 0.02), an effect that could not be seen when analyzing the dorsoventral group alone (p > 0.17, Fig. 2a; Table 2). A trend towards 3° higher kyphosis angles in X-rays in the lower thoracic region could be seen, but was not proven to be significant (Fig. 2a, p > 0.27). Regression analysis revealed a higher correlation coefficient r² for thoracal kyphosis (ranging from 0.47 through 0.61) than for lumbar lordosis (values around 0.14, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Differences in X-ray and MRI measurements for the kyphosis angle from Th2 through Th12 and the lordosis angles from Th12 through S1 (n = 60). Significant differences only exist in lumbar lordosis in the VDS group. b Regression analysis for thoracal kyphosis and lumbar lordosis

Table 2.

Number of measurements in the predefined regions, missing values and mean angles with single standard deviation (sag sagittal, cor coronal)

| COBB angle | Measure range | Total | Missing values (n) | Means | Standard deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | MRI | X-ray | MRI | X-ray | MRI | |||

| Thoracal kyphosis | sag Th3-11 | 60 | 15 | 0 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 14 |

| sag Th2-12 | 60 | 14 | 0 | 24 | 26 | 16 | 14 | |

| sag Th4-12 | 60 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 13 | |

| sag Th5-12 | 60 | 9 | 0 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 11 | |

| Lumbar lordosis | sag Th12-S1 | 60 | 8 | 3 | −52 | −46 | 14 | 13 |

| sag L1-S1 | 60 | 8 | 3 | −53 | −47 | 13 | 13 | |

| Thoracal a.p. curve | cor Th4-11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 46 | 6 | 10 |

| cor Th5-9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 31 | 3 | 1 | |

| cor Th5-11 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 18 | 5 | 4 | |

| cor Th5-12 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 32 | 29 | 10 | 11 | |

| cor Th6-11 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 23 | 11 | 9 | |

| cor Th6-12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 13 | 4 | 4 | |

| cor Th7-11 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 5 | |

| cor Th8-11 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 3 | 3 | |

| cor Th8-L1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 45 | 3 | 16 | |

| Total | 24 | 24 | 12 | 13 | ||||

| Lumbar a.p. curve | cor Th9-L3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 27 | 1 | 3 |

| cor Th11-L4 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 12 | 12 | |

| cor Th12-L4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | |

| cor L1-L4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 11 | 4 | 6 | |

| Total | 16 | 16 | 12 | 11 | ||||

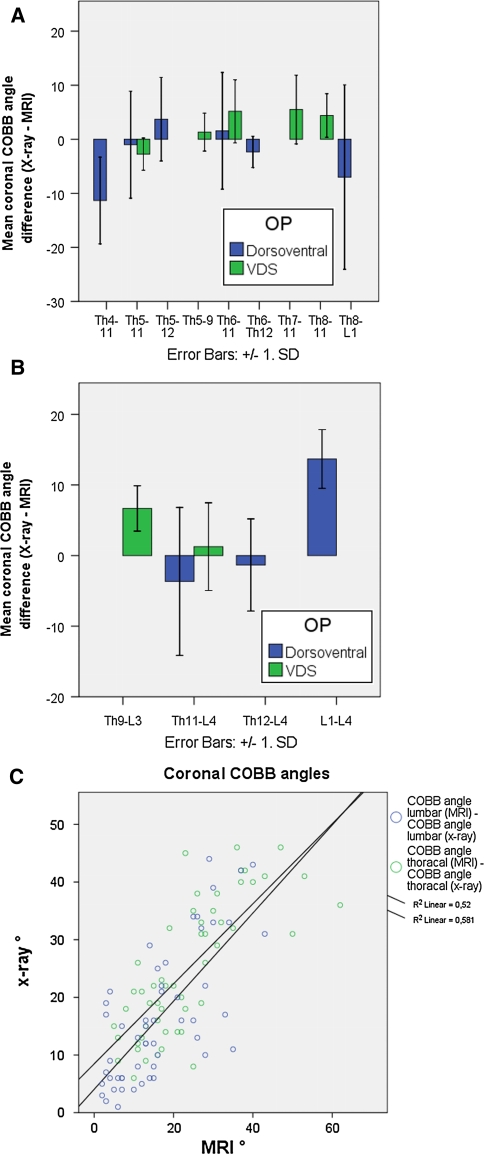

For coronal COBB angle measurements the comparison of standing X-ray and supine MRI did not show significant differences in any patient/any region (p > 0.84, Fig. 3a, b). This calculation is underlined by a high correlation of r² ranging from 0.52 through 0.58 (Fig. 3c). Moreover, when observing the groups alone, VDS (p > 0.27) and dorsoventral (p > 0.65) patients yielded comparable angle measurements in X-rays and in MRI. However, systematic deviation of the X-ray value from the MRI value could be observed in single cases (e.g. L1–L4, Fig. 3b; Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Differences in X-ray and MRI measurements for thoracal (a) and lumbar (b) coronal COBB angles in predefined regions (n = 60, for the case number distribution see Table 2). No significant differences could be observed. c Regression analysis for thoracal and lumbar COBB angles

Mean interobserver reliability for thoracal kyphosis angles was 94% in X-rays and 95% in MRI, for lumbar lordosis 29 versus 82% and for coronal COBB measurements 95 versus 87%.

Discussion

The 3D assessment of spinal deformity, e.g. scoliosis, is a topic of growing interest as the power of current correction techniques is enabling surgeons to control the coronal, sagittal and rotational aspects of the deformity. A crucial step in deformity analysis is still not taken: to exactly depict deformational aspects by radiographic technique. Whole-spine standing radiographs in standard frontal and sagittal projections are still the gold standard to evaluate global parameters, like CSVL and spinopelvic balance. However, this technique fails in the description of 3D orientation of the planes of regional curves [4]. Many techniques were developed to overcome this problem by the help of appropriate image analysis algorithms [5, 6]. In these studies, however, mean thoracic kyphosis angles of the subjects under investigation were rather normal (>30°) and no metal hardware was implanted.

Physical constraints of this biplanar radiographic technique, as there are the concealment of vertebrae by metal implants or the lungs cannot be solved by such algorithms [5]. In our study, regional analysis of thoracic kyphosis angles had to be done under realistic scoliosis circumstances (the mean thoracic kyphosis angle was around 20°). Additionally, X-ray and MRI image analysis was complicated by metal hardware. In our study we have shown, that in up to 90% of the cases X-ray sagittal measurement remained mere guesswork, due to invisibility of vertebral structures. In the contrary, more than 95% of the required sagittal regions were measurable in MRI (Fig. 4).

Astonishingly, interobserver reliability for both methods measuring thoracic kyphosis was still around 95%. Neither in the fused (dorsoventral group) nor in the thoracical mobile (VDS group) a significant difference between upright (X-ray) and supine (MRI) technique could be observed, suggesting validity of MRI for the measurement of thoracic kyphosis.

An explanation for the observed unsusceptibility of thoracic kyphosis angles might be the constrained motion in flexion/extension of the thoracic spine. Since now, however, this matter has not been investigated radiographically [7, 8].

The results from thoracic sagittal measurements must not be applied to lumbar lordosis. All patients under investigations had at least two mobile lumbar segments (L4/5 and L5/S1). These segments have been described as being the ones with the highest mobility, which make them susceptible to load and posture changes [9, 10]. This might be the explanation for significantly more negative lordosis angles in upright X-ray technique and thus a more pronounced lumbar lordosis, compared to supine MRI. Even when being put under axial load, supine MRIs produce less lordotic angles than standing radiographs [2].

Still, visibility remains a problem, as >50% of S1-vertebrae could not be detected properly in X-ray. There might be technique-related issues responsible for this low visibility. However, if one would develop the idea of sagittal profiling by MRI further, standing (not sitting—due to pelvic inclination) upright MRI might be the solution for the future, but would have its own difficulties like acquisition time and relative postural instability.

According to the already known numbers from the literature, our results suggest, that supine MRI measurement of coronal COBB angles is possible but one has to be aware of a possible systematic error.

Concluding, in our study we observed difficulties to visualize thoracic vertebrae in standing X-ray. The information about thoracic kyphosis can be safely obtained from supine MRI. For the future, applicability of this information has to be proven in the preoperative adolescent patient. To evaluate long-term results, to address sagittal balancing in a manner that equals the high standard of our therapeutic possibilities and, eventually, for an accurate way of surgical planning, we should aim at such a high level of diagnostic precision.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplemental Table 3

: Summary of sequence parameters.

Acknowledgments

The work of this study was kindly supported by Depuy Spine (Depuy GmbH, Kirkel, Germany).

Conflict of interest

The authors hereby disclose any support that would have biased parts or the whole content of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Torell G, Nachemson A, Haderspeck-Grib K, Schultz A. Standing and supine Cobb measures in girls with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10(5):425–427. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198506000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wessberg P, Danielson BI, Willen J. Comparison of Cobb angles in idiopathic scoliosis on standing radiographs and supine axially loaded MRI. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(26):3039–3044. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000249513.91050.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Street J, Lenehan B, Albietz J, Bishop P, Dvorak M, Fisher C. Intraobserver and interobserver reliabilty of measures of kyphosis in thoracolumbar fractures. Spine J. 2009;9(6):464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perdriolle R, Borgne P, Dansereau J, Guise J, Labelle H. Idiopathic scoliosis in three dimensions: a succession of two-dimensional deformities? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(24):2719–2726. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumas R, Blanchard B, Carlier R, Loubresse CG, Huec JC, Marty C, Moinard M, Vital JM. A semi-automated method using interpolation and optimisation for the 3D reconstruction of the spine from bi-planar radiography: a precision and accuracy study. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46(1):85–92. doi: 10.1007/s11517-007-0253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humbert L, Guise JA, Aubert B, Godbout B, Skalli W. 3D reconstruction of the spine from biplanar X-rays using parametric models based on transversal and longitudinal inferences. Med Eng Phys. 2009;31(6):681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brismee JM, Gipson D, Ivie D, Lopez A, Moore M, Matthijs O, Phelps V, Sawyer S, Sizer P. Interrater reliability of a passive physiological intervertebral motion test in the mid-thoracic spine. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2006;29(5):368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DG. Rotational instability of the mid-thoracic spine: assessment and management. Man Ther. 1996;1(5):234–241. doi: 10.1054/math.1996.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilton RC, Ball J, Benn RT. In vitro mobility of the lumbar spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979;38(4):378–383. doi: 10.1136/ard.38.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyasaka K, Ohmori K, Suzuki K, Inoue H. Radiographic analysis of lumbar motion in relation to lumbosacral stability. Investigation of moderate and maximum motion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(6):732–737. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.