Abstract

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder associated with reduced bone mineral density and the consequent high risk of bone fractures. Current practice relates osteoporosis largely with absolute mass loss. The assessment of variations in chemical composition in terms of the main elements comprising the bone mineral and its effect on the bone’s quality is usually neglected. In this study, we evaluate the ratio of the main elements of bone mineral, calcium (Ca), and phosphorus (P), as a suitable in vitro biomarker for induced osteoporosis. The Ca/P concentration ratio was measured at different sites of normal and osteoporotic rabbit bones using two spectroscopic techniques: Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). Results showed that there is no significant difference between samples from different genders or among cortical bone sites. On the contrary, we found that the Ca/P ratio of trabecular bone sections is comparable to cortical sections with induced osteoporosis. Ca/P ratio values are positively related to induced bone loss; furthermore, a different degree of correlation between Ca and P in cortical and trabecular bone is evident. This study also discusses the applicability of AES and EDX to the semiquantitative measurements of bone mineral’s main elements along with the critical experimental parameters.

Keywords: Ca/P ratio, Bone mineral, Apatite, Osteoporosis, Auger electron spectroscopy, Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, EDX, Calcium, Phosphorus

Introduction

Bone is an essential, dynamic, and highly complex connective tissue. The human skeletal system consists of 206 bones whose composition and structure vary with bone type and site, age, sex, and the presence of disorders. These disorders are considered as a critical, constant, and worldwide public health alarm since they are strongly related to morbidity, disability, and overall reduced life quality. Osteoporosis is characterized by a systemic impairment of bone mass and microarchitecture that results in a loss of bone strength and increased fracture risk [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined osteoporosis as a disease that can be categorized according to bone mineral density (BMD) measurements conveyed as T-scores [2]. Current clinical methods utilize dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) as the gold standard for in vivo noninvasive measurements for areal BMD. Although this approach has proven extremely valuable for clinical diagnosis and initiation of medical treatment, clinical trials confirm an inconsistent relationship between decreased BMD and fracture incidence in elderly men and women [3]. As demonstrated in the Rotterdam study, the diagnosis of osteoporosis based solely on densitometric measurements (T-score < −2.5), missed almost half of all non-vertebral future fractures in postmenopausal women; the percentage for men is even larger, although BMD is an equally important risk factor in both men and women [4].

The need for the development of more sensitive risk assessment tools led to the concept of bone quality. It is defined as a function of structural and compositional variables such as spatial distribution of the bone mass and the intrinsic properties of the molecular groups and atomic elements that comprise the bone [5, 6]. Thus, biophysical and biochemical bone properties affect strength, which is crucial for fracture risk [7–9]. Bone fracture constitutes the clinical outcome but physicochemical aptitude is the basis from which fragility stems. Therefore, discrepancies in bone composition might be used to elucidate experimental observations of trends in skeletal brittleness under diverse bone loading, among different bone sites, and during osteoporosis. At the molecular level, bone consists of water, an inorganic phase and a soft organic phase (98% w/v, mainly type I collagen), which surrounds the mineral crystals by a remarkably condensed filling [10]. The mineral inorganic phase in calcified tissues plays an important role, mostly because it affects their strength and quality. It is generally considered as a form of carbonated hydroxyapatite (Ca10[PO4]6[OH]2) containing a number of impurities in the form of HPO , CO

, CO , Mg2 + , Na + , F − and citrate, which are adsorbed onto the crystal surface and/or substituted in the lattice for Ca2 + , PO

, Mg2 + , Na + , F − and citrate, which are adsorbed onto the crystal surface and/or substituted in the lattice for Ca2 + , PO , and OH − ions [11] while citrate stabilizes the apatite nanocrystals [12]. The increased solubility due to the presence of these ions supports bone resorption [13].

, and OH − ions [11] while citrate stabilizes the apatite nanocrystals [12]. The increased solubility due to the presence of these ions supports bone resorption [13].

Ca and P are the main high Z elements of the mineral matrix and their concentrations vary independently. Ca is the most abundant cation in the body, with approximately 99% tied up in the mineral phase and partially released into the bloodstream through bone resorption. The remaining 1% is present within the extracellular and intracellular fluids. Likewise, body phosphate (approximately 85%) is present in the mineral phase of bone. Ca and phosphate interact in many fundamental processes in the body due to hormonal and physicochemical factors [14]. The relative content of Ca and P, however, is critical for sustaining mineral homeostasis and bone metabolism and their co-dependence is evident for bone growth and development [15]. It is therefore a suitable biomarker for the assessment of bone health [16], which an X-ray transmission technique, such as DXA, is physically unable to measure from relative mass variations of Ca and P in biological apatite. Furthermore, Ca/P ratio has been associated with rheumatoid arthritis and the generation of reactive oxygen species, which is an important factor for the development and maintenance of rheumatoid arthritis in humans [17]. All the above emphasize the importance of the application of analytical techniques capable of providing Ca and P distribution measurements in bone tissue.

The estimation of Ca/P ratio in bones is currently performed both in vivo and in vitro. The major advantage of the former is its non-invasive character, while in vitro studies frequently provide more accurate results due to the removal of fat, marrow, and collagen, which might obscure experimental measurements [18, 19]. In vitro bone elemental analysis has been performed using synchrotron radiation micro-CT [20, 21], neutron activation [22, 23], X-ray diffraction [24], small-angle X-ray scattering [25, 26], inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) combined with direct current argon arc plasma optical emission spectrometry (DCA ARC) [27], and chemical analysis [28]. Specifically related studies relying solely on spectroscopic methodologies include solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [29–31], X-ray fluorescence [32], TEM–EDX [33, 34], SEM-EDX [35], and relevant surface analysis techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [36, 37] and AES [38].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the Ca/P concentration ratio at different sites of normal and osteoporotic rabbit bones using two spectroscopic techniques, AES and EDX, in an effort to assess their applicability in the area of mineralized tissues. Our research group was the first to utilize AES for the determination of Ca/P at different sites of bone [38] and this study is also implemented as a continuation to our previous one to further examine the mineral phase at different sites and in relation to osteoporosis. AES provides high spatial resolution and surface sensitivity, permitting measurements of elemental concentrations throughout a wide range of the periodic table (with the exception of H and He). The Auger spectrum of a sample consists of peaks relevant to its atomic composition, revealing both qualitative and quantitative information. The characteristic energies of Auger excitations of Ca and P are well resolved and for this reason appropriate for reliable semiquantitative analysis with rapid acquisition times and featuring superior analytical detection limits of 0.3%. Experimental setup, however, remains a critical factor for proper data collection and interpretation due to the possible electron irradiation damage of the insulating biological tissues and the need for ultrahigh vacuum measurement conditions. These reasons, along with the intrinsically complicated nature of the effect, have limited its use, which initially focused mainly on dental tissues [39–43]. On the other hand, electron microscopy X-ray microanalysis is a powerful technique that has been extensively used in calcified tissue research [29, 44–47]. This technique is based on the X-ray energy dispersion generated by the accelerated electron bombardment of the sample surface. Elemental information from the bulk is provided by the Gaussian peaks of the characteristic emitted X-rays in the EDX spectrum. Typical background signal from Bremsstrahlung radiation due to the inelastic collisions of slowing electrons is also present. EDX is a sensitive qualitative and semiquantitative technique for the assessment of the mineral content variations in microscopic regions of bone with a spatial resolution of several cubic micrometers. In general, analytical resolution depends on the incident beam energy, the critical excitation energy for the X-rays of interest, the atomic weight, the atomic number and the density of the sample [48]. Quantitative information is based on the relative elemental abundance.

Both spectroscopic methods, AES and EDX, rely on the fact that when a specimen is irradiated with electrons, core electrons are ejected. Nevertheless, once an atom has been ionized it must return to ground state. Atomic relaxation when the vacant state is an inner state can be achieved through radiative and non-radiative decay process and, as a result, there is a competition between the emission of a characteristic X-ray photon and a characteristic Auger electron. The two processes do not have the same probability to occur and the emission of X-rays (fluorescence yield) is heavily correlated with atomic number, Z. The equation ωA = 1 − ωX , relates Auger yield, ωA, to the fluorescence yield, ωX. For light elements, Auger emission dominates, while X-ray yield increases sharply with high Z elements [49]. In the present study, we explore this de-excitation imbalance by combining both techniques to quantify the Ca/P ratio.

Materials and methods

Bone samples

Twenty New Zealand white rabbits, 8 months of age, were housed in two groups according to sex. Additionally, to a group of five female rabbits, of the same age, was induced inflammation-mediated osteoporosis (IMO) by subcutaneous injections of magnesium silicate (talkum) at sites distant from the skeleton, to stimulate an acute phase response. This IMO model suggests a decrease in osteoblast numbers and bone formation while osteoclast numbers and osteoclastic resorption are generally unaltered [50]. As previously reported, osteoporosis induced by this method strongly affects the skeletal Ca/P ratio [51]. All animals were housed and bred in natural conditions and euthanized under light ether anesthesia. All study protocols were approved by the Ioannina University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Unlike other mammals such as rats and mice, the skeletal maturity of rabbits is achieved at approximately 6 months, exhibiting noteworthy intra-cortical remodeling [52]. Cortical sections from the diaphysis of three different bone sites, femur, rear, and front tibias all from the right side, were dissected out and cleaned free of muscles and tendons. Using the same procedure, the trabecular sections of rib bones were separated while the edges were discarded. No signs of metabolic alterations of the bone tissues were noticed. Water removal was achieved by heating the samples to a maximum of 140°C for 4 days. Approximately 250 mg of ground bone material was converted into 2-mm-thick disk pellet of 8-mm diameter using a Specac hydraulic presser operating at 4-ton pumping pressure.

Data collection

AES

The experiments were carried out in an ultrahigh vacuum chamber with base pressure 10 − 9 mbar equipped with an electron gun and a cylindrical mirror electron analyzer. The excitation electron beam featured 1 keV and 0.5 mA energy and current, respectively. The AES signal was recorded in the first derivative mode, dN(E)/dE, and the intensity was measured from the peak-to-peak height, which is comparable to the Auger electron yield and therefore proportional to elemental concentrations. By using the derivative expression, system gain and sensitivity are improved considerably. Sharp peaks on a relatively small background are revealed instead of the original AES signal that features a large background originated from the secondary electrons’ inelastic scattering. The electron beam was rastered over an ellipsoid area with length of the major axis approximately 1 mm. Spectra were acquired over a 5-min period at 1 eV/step. No conductive coating was used.

EDX

The samples were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in a Jeol JSM 5600 system configured with an EDX detector operating at 20-kV accelerating voltage and 20-mm working distance. The EDX data were compiled for analysis using the Link ISIS system (Oxford Instruments, UK). The Ca/P ratio was calculated using the accompanying ZAF-correction software (SEMQuant, Oxford Instruments). Reference standards and synthetic pure samples with similar Ca/P ratio (tricalcium phosphate, Ca3(PO4)2, and hydroxyapatite) were used for calibration. Prior to each session, the sample with the standard Ca/P ratio was measured and ZAF (Z: atomic number, A: X-ray absorption, F: secondary X-ray fluorescence) evaluated. The smooth surface of all pellets was coated with a conductive carbon layer using a JEOL JEE-4X Vacuum Evaporator.

Electron beam damage

The electron beam can induce significant damage in biological tissues. The sample’s surface is most sensitive to beam interactions and effects such as elemental adsorption, desorption, decomposition, etching, oxidation, diffusion, amorphization, and heating may modify significantly its atomic and molecular composition. Biological samples are inherently insulating and therefore more susceptible to the above factors [53]. Hence, we performed extensive tests on the operating conditions of the spectrometers by acquiring sequential spectra of standard synthetic and bone samples.

In Auger experiments, the critical parameters are the density of the primary beam, the acquisition time, and the raster scan facility of the apparatus. The latter prevents beam-induced diffusion of phosphorus, which is a typical side-effect with steady electron beams upon hydroxyapatite’s surface [54]. The acquisition of sequential spectra verified that no deteriorating phenomena occurred since no significant alterations of the peaks, regarding their energy, shape and intensity, were detected. Likewise, visual examination revealed that the samples’ surface remained unchanged within the acquisition timeframe. Current density value was kept one magnitude of order lower than the literature’s damage threshold value of 5 × 10 − 2 A.cm − 2 [54].

In EDX experiments, the critical parameters are accelerating voltage, scan time, magnification, sample coating, and beam spot size [55, 56]. Irradiating a specimen with an electron beam results in energy transfer to the sample in the form of heat, which can lead to specimen damage. A higher value of kV results in higher temperatures and possible higher surface damage. The Bethe equation describes the energy loss due to inelastic scattering-induced electronic excitations along the particle trajectories [57]. At higher beam energies, the effect of electronic excitations, which produce the X-rays, is extended to larger penetration depths, justifying them as responsible for possible radiolysis effects. Since voltage is directly related to radiation damage rates, scan time must be as short as possible. The criterion must be peak resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. Temperature levels at the surface of bone specimens are also positively related to the degree of magnification [58], which in our experiments was kept to low values. Carbon coating prevents charging effects but also reduces the effects of beam damage [59] without compromising the validity of EDX results for calcified tissues [60] provided that it does not contribute to the signal as in the present case with Ca and P measurements. Finally, a larger beam spot size for a given energy can be achieved by increasing the working distance. Poor refinement of the above factors may lead to observable damage, described as “bleaching” [61], where irradiated bone regions become remarkably brighter in backscattered electron (BSE) imaging due to mass loss (i.e., loss of phosphorus which is complemented by loss in oxygen or carbon). Thus, by taking beam effects into account, we measured twice each spectrum until a total collection time of 60 s was reached. No significant divergence between each measurement of the Ca/P ratio was found. Final estimation was attained from the mean Ca/P value of two different locations of the specimen.

Statistical analysis

PRISM software (GRAPHPAD software, San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized for the statistical analysis of the results. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance of differences of mean values was calculated via one-way ANOVA and unpaired t test. The normality of data was confirmed by the application of a D’Agostino–Pearson test. Statistical significance was considered at p ≤ 0.05.

Results and discussion

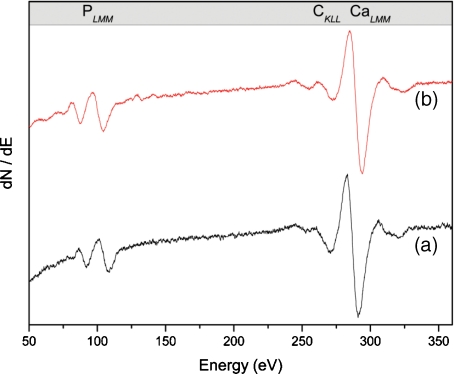

Typical AES spectra from homogenized rear tibia cortical normal and osteoporotic bone are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Auger electron spectra of ground cortical bone (rear tibia); (a) normal bone (b) osteoporotic bone

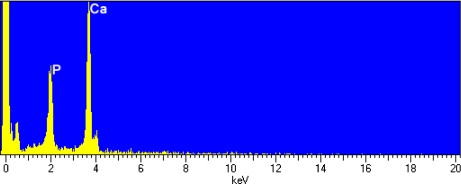

Since the experimental substrate is typical hydroxyapatite, we do not expect noticeable dissimilarities among different samples. CaLMM Auger transition is well defined at 280–290 eV, while peaks recognized at 90–110 eV and near 260 eV correspond to the PLMM and CKLL transitions, respectively. The carbon 1s peak is attributed to the carbonate apatitic environment of bone and not to beam-induced carbon contamination, which is generally not observed in ground homogenized materials [38]. Bone sections, however, usually sustain this effect, probably due to the evolution of a Ca-deficient carbonated apatitic phase at the surface and the grain boundaries of bone hydroxyapatite polycrystalline specimens [62]. Such an impurity adsorption EDX spectrum is also typical of hydroxyapatite-like samples featuring distinct (relative to the X-ray continuum) characteristic peaks at 3.7 KeV for Ca and 2.0 Kev for P, and consistent Kα emission lines (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

EDX spectrum of ground cortical bone (rear tibia)

The complexity of the phenomena involved in the spectroscopic techniques triggered by electron beams, as described, makes accurate quantitative analysis extremely difficult. Thus, we have employed semiquantitative analysis for the determination of the Ca/P ratio. Ratio techniques have the advantage of canceling out systematic errors and instrumental parameters (such as the incident angle of the primary beam). However, since hydroxyapatite is a multi-element molecular material, relative sensitivity factors accounting for matrix effects should be considered. Measured intensities need to be corrected for differences in atomic density and electron backscattering affecting both techniques as well as for inelastic mean free path (IMFP) for AES and X-ray cross section and absorption for EDX.

Regarding AES, IMFP is the most critical issue influencing sensitivity for the matrix effects in a sample’s superficial volume. We determined relevant IMFP values from the predictive Tanuma–Powell–Penn (TPP-2M) equation [63]. TPP-2M can be used for any solid and is derived from experimental optical data by fitting a modified form of the Bethe IMFPs calculated for a broad energy range (0.05–2 keV). We have used the molecular form of pure hydroxyapatite as input to the SESSA software package [64] for computer-simulated AES spectra and for the calculations regarding IMFP and matrix-related parameters. The experimental Ca/P error found with this technique was estimated to approximately 4%.

As stated above, the physical origin of matrix effects in EDX, for multi-element samples, stems from differences in elastic and inelastic scattering and in the propagation of X-rays towards the detector. Although ZAF corrections have limited success in soft biological samples, they have been applied effectively in the case of hydroxyapatite [29, 55]. The experimental Ca/P error with this procedure was evaluated to 1–2%.

Bulk atomic Ca/P ratios as estimated by AES regarding cortical vs. trabecular specimens and male vs. female groups are summarized in Table 1. Female normal vs. osteoporotic Ca/P bone ratios from AES and EDX experiments are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Experimental results (mean±SD) of Ca/P ratio for cortical and trabecular bone

| Normal bone AES | Bone site | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Rear tibia | Femur | Front tibia | Rib | |

| Male | 2.07 ± 0.12 | 2.08 ± 0.13 | 2.06 ± 0.09 | 1.97 ± 0.05 | |

| Female | 2.07 ± 0.09 | 2.08 ± 0.08 | 2.11 ± 0.08 | 1.95 ± 0.05 | |

Table 2.

Ca/P results (mean±SD) comparison for the two spectroscopic techniques for normal and osteoporotic bone

| Female Bone | Condition | Bone site | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rear tibia | Femur | Front tibia | Rib | ||

| AES | Normal | 2.07 ± 0.09 | 2.08 ± 0.08 | 2.11 ± 0.08 | 1.95 ± 0.05 |

| Osteoporotic | 1.86 ± 0.09 | 1.90 ± 0.12 | 1.92 ± 0.07 | 1.83 ± 0.11 | |

| EDX | Normal | 2.10 ± 0.05 | 2.17 ± 0.09 | 2.14 ± 0.04 | 1.88 ± 0.04 |

| Osteoporotic | 1.92 ± 0.03 | 1.94 ± 0.04 | 1.97 ± 0.07 | 1.80 ± 0.05 | |

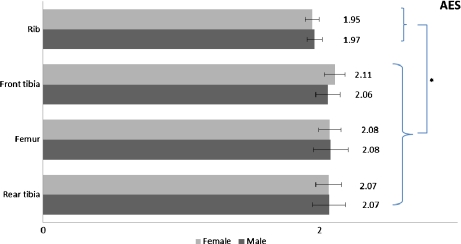

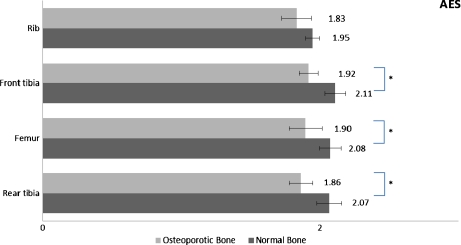

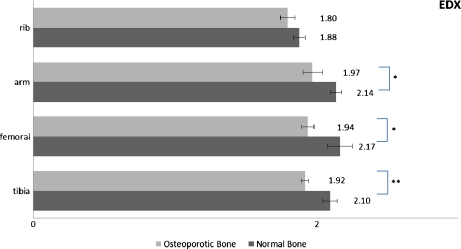

Statistically significant variations are illustrated graphically in Figs. 3, 4, 5. Results concerning normal bone reveal no significant differences (0.3 < p < 0.9) for Ca/P ratio between sex groups for the same bone site, confirming previous studies [35, 61, 65]. Trabecular bone apatite features lower Ca/P ratio in a statistically significant manner (0.01 < p < 0.03). Generally, trabecular bone is less mineralized and rich in carbonate content while it undergoes higher rates of thermal conversion into β-tricalcium phosphate due to the relatively lower Ca/P ratio [66, 67]. Its structural connectivity is different and it is metabolically more active than cortical bone with higher surface area per volume and higher rates of turnover [68]. These parameters (among others such as bone dimensions and microarchitecture) [69] affect bone strength, and trabecular bone exhibits higher susceptibility to fracture. In our case, the significantly lower Ca/P ratio of trabecular sections probably reflects the remodeling-induced formation of the “younger” trabecular bone. The difference of Ca/P ratio between trabecular and cortical bone, albeit not to this statistical power, also stands in the case of osteoporotic female bone sites.

Fig. 3.

Significant differences of Ca/P ratio among bone sites for the two rabbit sex populations (*: p < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

Significant differences of Ca/P ratio among bone sites for the normal vs. osteoporotic female bone as measured by AES ( ∗ : p < 0.05)

Fig. 5.

Significant differences of Ca/P ratio among bone sites for the normal vs. osteoporotic female bone as measured by EDX ( ∗ : p < 0.05, ∗ ∗ : p < 0.01)

There is no significant difference (p = 0.07) of the Ca/P ratio in trabecular bones between IMO (osteoporotic) samples and controls. Thus, changes in the degree of mineralization for trabecular bone under osteoporosis are minimal, or there is a strong correlation between Ca and P concentrations, which decline proportionally. Since trabecular sections constitute most of the bone tissue of the axial skeleton, playing a major role in calcium and phosphate metabolism, we conclude that the increased incidence of spinal and rib fractures under osteoporotic conditions is directly related to bone mass loss and to possibly reduced concentrations of Ca and P under a constant Ca/P ratio scheme. This finding is evident from both AES and EDX.

In contrast, Ca/P ratios of cortical bone are significantly reduced in all osteoporotic cases compared to controls. All bone sites are affected and results are directly comparable between AES and EDX. This corroborates earlier observations that relative content of Ca in femoral sections of osteoporotic groups is significantly lower than in the control group, while a strong positive correlation between Ca and P still exists [70]. Cortical bone has a slow turnover rate and low porosity (5–10%) and its minerals are susceptible to less ionic substitution than the minerals within trabeculae. The proposed mechanism of cortical bone loss refers to trabecularization of the endocortical surface and to increased cortical porosity [3]. This is further supported by our Ca/P measurements, which reveal similar ratios between trabecular and osteoporotic cortical bone samples. The whole procedure is strongly related to bone mineral mass reduction but it is also accompanied by non-proportional concentration changes of Ca and P in this case. Our experimental protocol involves measuring a given volume of ground materials and therefore excluded any errors related to cortical porosity of raw bone sections possibly affecting results originating from BMD measurements.

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that there is a relationship between induced bone loss and lowered Ca/P ratio, which is also associated with a different correlation between these two elements in cortical and trabecular bone, respectively. Our results suggest that bone quality, in addition to bone density, plays an important role in bone strength, and is strongly related to the Ca/P ratio. Therefore, it might be possible to use this biomarker for the effective diagnostic and classification criteria of osteoporosis and related diseases. Ca/P ratio is not distributed homogenously along the osteoporotic bone [71] and high Ca/P regions could form a potential criterion to enhance our perspective on osteoporosis treatment and monitoring. This might be of particular importance regarding the male population since the time needed for evaluation of response to pharmaceutical treatment using BMD only tends to be at least 2 years [72].

A novelty of this study is the introduction of two complementary spectroscopic techniques for the reliable determination of hydroxyapatite’s high Z elements. We found that both AES and EDX are suitable analytical methods for quantifying, in vitro, the main elements comprising bone mineral in the form of Ca/P ratio. As discussed, if the experimental conditions are carefully adjusted, they demonstrate high precision for semiquantitative measurements, permitting improved statistical significance for the Ca/P ratio compared to the error-prone simple composition assessment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Assoc. Prof. P. Patsalas for providing the Auger facility and for helpful suggestions, and the Horizontal Laboratory Network, University of Ioannina, for the SEM-EDX.

References

- 1.Rachner TD, Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis: now and the future. Lancet. 2011;377:1276–1287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62349-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanis JA, Alexeeva L, Bonjour JP, Burkhardt P, Christiansen C, Cooper C, Delmas P, Johnell O, Johnston C, Kanis JA, Khaltaev N, Lips P, Mazzuoli G, Melton LJ, Meunier P, Seeman E, Stepan J, Tosteson A. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis—synopsis of a WHO report. Osteoporos. Int. 1994;4:368–381. doi: 10.1007/BF01622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeLaet CEDH. Bone density and risk of hip fracture in men and women: cross sectional analysis. Br. Med. J. 1997;315:221–225. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7102.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuit SCE, Klift M, Weel AEAM, Laet CEDH, Burger H, Seeman E, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Leeuwen JPTM, Pols HAP. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam study. Bone. 2004;34:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouxsein ML, Seeman E. Quantifying the material and structural determinants of bone strength. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009;23:741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Einhorn TA. Bone strength: the bottom line. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1992;51:333–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00316875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanis JA, Melton LJ, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1994;9:1137–1141. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings SR, Cauley JA, Palermo L, Ross PD, Wasnich RD, Black D, Faulkner KG. Racial differences in hip axis lengths might explain racial differences in rates of hip fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 1994;4:226–229. doi: 10.1007/BF01623243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black DM, Bouxsein ML, Marshall LM, Cummings SR, Lang TF, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Nielson CM, Orwoll ES. Proximal femoral structure and the prediction of hip fracture in men: a large prospective study using QCT. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23:1326–1333. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrey JD. Bones: Structure and Mechanics. NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harst MR, Brama PAJ, Lest CHA, Kiers GH, DeGroot J, Weeren PR. An integral biochemical analysis of the main constituents of articular cartilage, subchondral and trabecular bone. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2004;12:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu YY, Rawal A, Schmidt-Rohr K.Strongly bound citrate stabilizes the apatite nanocrystals in bone Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 201010722425–22429.2010PNAS..10722425H 10.1073/pnas.1009219107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn AJ, Partridge NC. Bone. Vol. 2: The Osteoclast: Bone Resorption In Vivo. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peacock M. Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;5:23–30. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05910809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro R, Heaney RP. Co-dependence of calcium and phosphorus for growth and bone development under conditions of varying deficiency. Bone. 2003;32:532–540. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coats AM, Zioupos P, Aspden RM. Material properties of subchondral bone from patients with osteoporosis or osteoarthritis by microindentation testing and electron probe microanalysis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2003;73:66–71. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-2080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oelzner P, Muller A, Deschner F, Huller M, Abendroth K, Hein G, Stein G. Relationship between disease activity and serum levels of vitamin D metabolites and PTH in rheumatoid arthritis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1998;62:193–198. doi: 10.1007/s002239900416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fountos G, Yasumura S, Glaros D. The skeletal calcium/phosphorus ratio: a new in vivo method of determination. Med. Phys. 1997;24:1303–1310. doi: 10.1118/1.598152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolotin HH, Sievanen H. Inaccuracies inherent in dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in vivo bone mineral density can seriously mislead diagnostic/prognostic interpretations of patient-specific bone fragility. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001;16:799–805. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tzaphlidou M, Speller R, Royle G, Griffiths J. Preliminary estimates of the calcium/phosphorus ratio at different cortical bone sites using synchrotron microCT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006;51:1849–1855. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/7/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neues F, Epple M. X-ray microcomputer tomography for the study of biomineralized endo- and exoskeletons of animals. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:4734–4741. doi: 10.1021/cr078250m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaichick V, Tzaphlidou M. Determination of calcium, phosphorus, and the calcium/phosphorus ratio in cortical bone from the human femoral neck by neutron activation analysis. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2002;56:781–786. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(02)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzaphlidou M, Zaichick V. Neutron activation analysis of calcium/phosphorus ratio in rib bone of healthy humans. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2002;57:779–783. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(02)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa K, Ducheyne P, Radin S. Determination of the Ca/P ratio in calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite using X-ray diffraction analysis. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 1993;4:165–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00120386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley DA, Farquharson MJ, Gundogdu O, Al-Ebraheem A, Ismail EC, Kaabar W, Bunk O, Pfeiffer F, Falkenberge G, Bailey M.Applications of condensed matter understanding to medical tissues and disease progression: Elemental analysis and structural integrity of tissue scaffolds Radiat. Phys. Chem. 201079162–175.2010RaPC...79..162B 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2008.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey MJ, Coe S, Grant DM, Grime GW, Jeynes C. Accurate determination of the Ca: P ratio in rough hydroxyapatite samples by SEM-EDS, PIXE and RBS – a comparative study. X-Ray Spectrom. 2009;38:343–347. doi: 10.1002/xrs.1171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milovanovic P, Potocnik J, Stoiljkovic M, Djonic D, Nikolic S, Neskovic O, Djuric M, Rakocevic Z. Nanostructure and mineral composition of trabecular bone in the lateral femoral neck: Implications for bone fragility in elderly women. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:3446–3451. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akesson K, Grynpas MD, Hancock RGV, Odselius R, Obrant KJ. Energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis of the bone mineral content in human trabecular bone: a comparison with ICPES and neutron activation analysis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1994;55:236–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00425881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu JD, Zhu PZ, Gan ZH, Sahar N, Tecklenburg M, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Ramamoorthy A. Natural-abundance Ca-43 solid-state NMR spectroscopy of bone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11504–11509. doi: 10.1021/ja101961x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Ackerman JL, Strawich ES, Rey C, Kim HM, Glimcher MJ. Phosphate ions in bone: Identification of a calcium-organic phosphate complex by P-31 solid-state NMR spectroscopy at early stages of mineralization. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2003;72:610–626. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu YT, Ackerman JL, Kim HM, Rey C, Barroug A, Glimcher MJ. Nuclear magnetic resonance spin-spin relaxation of the crystals of bone, dental enamel, and synthetic hydroxyapatites. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002;17:472–480. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hübler R, Blando E, Gaião L, Kreisner PE, Post LK, Xavier CB, Oliveira MG. Effects of low-level laser therapy on bone formed after distraction osteogenesis. Laser Med. Sci. 2010;25:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassella JP, Garrington N, Stamp TCB, Ali SY. An electron-probe X-ray microanalytical study of bone mineral in osteogenesis imperfecta. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1995;56:118–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00296342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benhayoune H, Charlier D, Jallot E, Laquerriere P, Balossier G, Bonhomme P.Evaluation of the Ca/P concentration ratio in hydroxyapatite by STEM-EDXS: influence of the electron irradiation dose and temperature processing J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 200134141–147.2001JPhD...34..141B 10.1088/0022-3727/34/1/321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kourkoumelis N, Tzaphlidou M. Spectroscopic assessment of normal cortical bone: differences in relation to bone site and sex. TheScientificWorldJOURNAL. 2010;10:402–412. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe K, Okawa S, Kanatani M, Homma K. Surface analysis of commercially pure titanium implant retrieved from rat bone. Part 1: Initial biological response of sandblasted surface. Dent. Mater. J. 2009;28:178–184. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zoehrer R, Perilli E, Kuliwaba J, Shapter J, Fazzalari N, Voelcker N. Human bone material characterization: Integrated imaging surface investigation of male fragility fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2011;1111:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1688-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balatsoukas I, Kourkoumelis N, Tzaphlidou M. Auger electron spectroscopy for the determination of sex and age related Ca/P ratio at different bone sites. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;108:74701. doi: 10.1063/1.3490118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller RG, Bowles CQ, Eick JD, Gutshall PL. Auger electron spectroscopy of dentin: Elemental quantification and the effects of electron and ion bombardment. Dent. Mater. 1993;9:280–285. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(93)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wieliczka DM, Spencer P, Kruger MB, Eick JD. Spectroscopic characterization of the dentin/adhesive interface. J. Dent. Res. 1996;75:1758–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korn D, Soyez G, Elssner G, Petzow G, Bres EF, d’Hoedt B, Schulte W. Study of interface phenomena between bone and titanium and alumina surfaces in the case of monolithic and composite dental implants. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 1997;8:613–620. doi: 10.1023/A:1018567302700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang BS, Sul YT, Oh SJ, Lee HJ, Albrektsson T. XPS, AES and SEM analysis of recent dental implants. Acta. Biomater. 2009;5:2222–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones FH.Teeth and bones: applications of surface science to dental materials and related biomaterials Surf. Sci. Rep. 20014275–205.2001SurSR..42...75J 10.1016/S0167-5729(00)00011-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obrant KJ, Odselius R. Electron-microprobe investigation of calcium and phosphorus concentration in human-bone trabeculae—both normal and in posttraumatic osteopenia. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1985;37:117–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02554829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rai DV, Darbari R, Aggarwal LM. Age-related changes in the elemental constituents and molecular behaviour of bone. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;42:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kolroser G, Kasimir MT, Eichmair E, Nigisch A, Simon P, Weigel G. Scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis: a valuable tool for studying cell surface antigen expression on tissue-engineered scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Pt. C: Meth. 2009;15:257–263. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roschger P, Fratzl P, Klaushofer K, Rodan G. Mineralization of cancellous bone after alendronate and sodium fluoride treatment: a quantitative backscattered electron imaging study on minipig ribs. Bone. 1997;20:393–397. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanaya K, Okayama S.Penetration and energy-loss theory of electrons in solid targets J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1972543–58.1972JPhD....5...43K 10.1088/0022-3727/5/1/308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krause MO, Oliver JH.Natural widths of atomic K and L levels, Kα X-ray lines and several KLL Auger lines J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 19798329–338.1979JPCRD...8..329K 10.1063/1.555595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armour KJ, Armour KE. Methods in Molecular Medicine, Vol. 80: Bone Research Protocols: Inflammation-Induced Osteoporosis, The IMO Model. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Speller R, Pani S, Tzaphlidou M, Horrocks J.MicroCT analysis of calcium/phosphorus ratio maps at different bone sites Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 2004548269–273.2005NIMPA.548..269S 10.1016/j.nima.2005.03.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner AS. Animal models of osteoporosis—necessity and limitations. Eur. Cells Mater. 2001;1:66–81. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v001a08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pignatel GU, Queirolo G. Electron and ion beam effects in Auger electron spectroscopy on insulating materials. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids. 1983;79:291–303. doi: 10.1080/00337578308207412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanraemdonck W, Ducheyne P, Demeester P. Auger-electron spectroscopic analysis of hydroxylapatite coatings on titanium. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1984;67:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1984.tb19721.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bloebaum RD, Holmes JL, Skedros JG. Mineral content changes in bone associated with damage induced by the electron beam. Scanning. 2005;27:240–248. doi: 10.1002/sca.4950270504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Egerton RF, Li P, Malac M. Radiation damage in the TEM and SEM. Micron. 2004;35:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emfietzoglou D, Kyriakou I, Garcia-Molina R, Abril I, Kostarelos K.Analytic expressions for the inelastic scattering and energy loss of electron and proton beams in carbon nanotubes J. Appl. Phys. 2010108543122010JAP...108E4312E 10.1063/1.3463405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holmes JL, Bachus KN, Bloebaum RD. Thermal effects of the electron beam and implications of surface damage in the analysis of bone tissue. Scanning. 2000;22:243–248. doi: 10.1002/sca.4950220403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walther P, Wehrli E, Hermann R, Müller M. Double-layer coating for high-resolution low-temperature scanning electron microscopy. J. Microsc. 1995;179:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1995.tb03635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vajda EG, Skedros JG, Bloebaum RD. Errors in quantitative backscattered electron analysis of bone standardized by energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry. Scanning. 1998;20:527–535. doi: 10.1002/sca.1998.4950200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boyce TM, Bloebaum RD, Bachus KN, Skedros JG. Reproducible method for calibrating the backscattered electron signal for quantitative assessment of mineral-content in bone. Scanning Microsc. 1990;4:591–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suetsugu Y, Hirota K, Fujii K, Tanaka J.Compositional distribution of hydroxyapatite surface and interface observed by electron spectroscopy J. Mater. Sci. 1996314541–4544.1996JMatS..31.4541S 10.1007/BF00366349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanuma S, Powell CJ, Penn DR. Calculations of electron inelastic mean free paths. VIII. Data for 15 elemental solids over the 50–2000 eV range. Surf. Interface Anal. 2005;37:1–14. doi: 10.1002/sia.1997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smekal W, Werner WSM, Powell CJ. Simulation of electron spectra for surface analysis (SESSA): a novel software tool for quantitative Auger-electron spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Surf. Interface Anal. 2005;37:1059–1067. doi: 10.1002/sia.2097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tzaphlidou M, Zaichick V. Sex and age related Ca/P ratio in cortical bone of iliac crest of healthy humans. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2004;259:347–349. doi: 10.1023/B:JRNC.0000017316.20693.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuhn LT, Grynpas MD, Rey CC, Wu Y, Ackerman JL, Glimcher MJ. A comparison of the physical and chemical differences between cancellous and cortical bovine bone mineral at two ages. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2008;83:146–154. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9164-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bigi A, Cojazzi G, Panzavolta S, Ripamonti A, Roveri N, Romanello M, Suarez KN, Moro L. Chemical and structural characterization of the mineral phase from cortical and trabecular bone. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1997;68:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S0162-0134(97)00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lipschitz S. Advances in understanding bone physiology: influences of treatment. Menopause Update. 2009;12:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ammann P, Rizzoli R. Bone strength and its determinants. Osteoporos. Int. 2003;14:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fei YR, Zhang M, Li M, Huang YY, He W, Ding WJ, Yang JH. Element analysis in femur of diabetic osteoporosis model by SRXRF microprobe. Micron. 2007;38:637–642. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tzaphlidou M, Speller R, Royle G, Griffiths J, Olivo A, Pani S, Longo R. High resolution Ca/P maps of bone architecture in 3D synchrotron radiation microtomographic images. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2005;62:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cummings SR, Palermo L, Browner W, Marcus R, Wallace R, Pearson J, Blackwell T, Eckert S, Black D, Gr FITR. Monitoring osteoporosis therapy with bone densitometry—Misleading changes and regression to the man. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000;283:1318–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.10.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]