Abstract

Our objective was to determine the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability and lymph node uptake of the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, labeled with the near-infrared (IR) dye 800CW, after intravenous (IV) and subcutaneous (SC) administration in mice. Fluorescence imaging and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays were developed and validated to measure the concentration of bevacizumab in plasma. The bevacizumab–IRDye conjugate remained predominantly intact in plasma and in lymph node homogenate samples over a 24-h period, as determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and size exclusion chromatography. The plasma concentration vs. time plots obtained by fluorescence and ELISA measurements were similar; however, unlike ELISA, fluorescent imaging was only able to quantitate concentrations for 24 h after administration. At a low dose of 0.45 mg/kg, the plasma clearance of bevacizumab was 6.96 mL/h/kg after IV administration; this clearance is higher than that reported after higher doses. Half-lives of bevacizumab after SC and IV administration were 4.6 and 3.9 days, respectively. After SC administration, bevacizumab–IRDye800CW was present in the axillary lymph nodes that drain the SC site; lymph node uptake of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW was negligible after IV administration. Bevacizumab exhibited complete bioavailability after SC administration. Using a compartmental pharmacokinetic model, the fraction absorbed through the lymphatics after SC administration was estimated to be about 1%. This is the first report evaluating the use of fluorescent imaging to determine the pharmacokinetics, lymphatic uptake, and bioavailability of a near-infrared dye-labeled antibody conjugate.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1208/s12248-012-9342-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key words: bevacizumab, bioavailability, fluorescence imaging, lymphatic absorption, pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Bevacizumab (rhuMAb VEGF) is a humanized variant of the anti-VEGF-A monoclonal antibody A.4.6.1 that binds to human VEGF-A (1). Bevacizumab was approved in 2004 for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in combination with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy (2). In 2006, bevacizumab was also approved for the initial systemic treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel (3). In 2009, FDA granted accelerated approval to bevacizumab for patients with glioblastoma multiforme with progressive disease following prior therapy (4). For all of the above indications, the recommended route of administration is by intravenous infusion.

There is interest in the delivery of monoclonal antibodies via subcutaneous (SC) or other non-IV routes; however, bioavailability can be variable following SC administration in humans, with estimates varying from 50% to 100% (5). Here, we use bevacizumab (molecular weight (MW) of 149 kDa) as a model antibody to investigate its lymphatic uptake and bioavailability after SC administration in a mouse model. Based on studies performed in a sheep model, it was reported that the lymphatics represent the primary absorptive pathway for molecules with MWs greater than ∼16 kDa after SC administration (6), but estimates of lymphatic uptake in rats suggest that the lymphatics may not play a prominent role (7,8). Little is known about lymphatic uptake in the mouse after SC administration. If the protein drugs are not removed or degraded in the lymphatic system, proteins will enter the bloodstream through the thoracic or other lymph ducts, contributing to the bioavailability of the proteins.

In this study, we characterize, for the first time, the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and lymph node exposure of near-infrared dye-labeled antibody conjugate after SC and IV administration. A fluorescence imaging assay was developed and validated to detect bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW in the plasma of mice. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method for measuring the plasma concentration of bevacizumab was also developed for confirming the fluorescence imaging results. Both assays were successfully applied to study the pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW after IV and SC administration in SKH-1 mice. Also, the accumulation of bevacizumab labeled with an infrared dye, IRDye 800CW, in the lymph nodes draining the SC site was quantitatively determined using ELISA. A mechanistic compartmental pharmacokinetic model was developed to simultaneously fit the plasma and lymph node bevacizumab concentrations after IV and SC administration of bevacizumab and estimate the fraction absorbed through the lymphatics after SC administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

IRDye 800CW protein labeling-High MW kit was purchased from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE, USA). Avastin® (bevacizumab, 25 mg/mL; Genentech, CA, USA) was purchased. Laemmli sample buffer, Tris/glycine/ sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) running buffer, 2-mercaptoethanol, Bio-safe Coomassie, and ready-gel TBE gel (10% precast polyacrylamide gel) were purchased from Bio-Rad life science (Hercules, CA, USA). Human IgG ELISA kit was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories, Inc (Montgomery, TX, USA). Isoflurane was obtained from Hospira Inc. (Lake Forest, IL, USA). Pierce Zeba™ desalting spin columns were obtained from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, USA).

Methods

Conjugation of Antibody with Fluorescent Dye

Using an IRDye 800CW protein labeling kit, 1 mg bevacizumab was conjugated with IRDye 800CW according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the pH of 1 mL of 1 mg/mL bevacizumab in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution was adjusted to 8.5 by adding 0.1 mL of 1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 9). Then, 23 μL of 3.4 mM IRDye 800–N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester in water was added drop by drop into the above bevacizumab solution, and the solution was kept at room temperature for 2 h in the dark. The reaction molar ratio of IRDye 800CW to bevacizumab was 12:1. After the conjugation, the reaction solution was then loaded on a Pierce Zeba™ desalting spin column (5 mL, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) and centrifuged at 1,000×g for 2 min to remove the free dye. The bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW was stored at −20°C until use.

Characterization of the Bevacizumab-IRDye 800CW Conjugates

To calculate the dye and bevacizumab labeling ratio (dye over protein ratio, D/P) for the bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugates, the conjugates were diluted with PBS/methanol (9:1). A UV-visible spectrophotometer PharmaSpec UV-1700 (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA) was used to determine the absorbance of the bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugates at 280 (A280) and 780 nm (A780). The molar extinction coefficient at 780 nm of IRDye 800CW (ε Dye) was measured as 260,000 M−1 cm−1 in a 9:1 mixture of PBS/methanol. The molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm of bevacizumab (ε bevacizumab) was calculated based on Beer’s law and the absorbance of a 1 mg/mL solution of unlabeled bevacizumab in PBS/methanol (9:1) solution at 280 nm. The D/P ratio and the final bevacizumab concentration were calculated according to the manufacturer’s information (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA).

Reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed to confirm the conjugation of bevacizumab with IRDye 800CW using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) electrophoresis system. Briefly, 8 μL of 500 μg/mL of bevacizumab IRDye 800CW conjugate or 500 μg/mL of bevacizumab in PBS solution was mixed with 12 μL of sample buffer (Bio-Rad, 2% SDS w/v, 25% glycerol v/v, 0.001% bromophenol blue w/v, 62.5 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8) with 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 10 μL of each mixture was loaded and separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoresis was carried out at a constant current (200 V) for 30 min. After taking fluorescent images using the customized filter set (excitation, 710 to 760 nm; emission, 800 nm long-pass) with the Maestro in vivo imaging system (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Inc. (CRI), Woburn, MA, USA), the gel was stained with BIO-RAD Bio-safe Coomassie and then imaged using the Maestro imaging system under white light.

In Vitro Stability of Bevacizumab IRDye 800CW Conjugate in Plasma and Lymph Node Homogenate

Stability of IRDye-800CW-labeled bevacizumab was determined in plasma and lymph node homogenates by using SDS-PAGE, as described above. Blank lymph nodes were homogenized in tissue protein extraction reagent (T-PER) (20:1, v/w (milliliters/grams)). Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugates were incubated in blank plasma or lymph node homogenate at 37°C for up to 7 days. Plasma or lymph node samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE at 200 V for 30 min as previously described. Then, the SDS-PAGE gel was subjected to fluorescence imaging using the customized filter set (excitation, 710 to 760 nm; emission, 800 nm long-pass) with the Maestro in vivo imaging system.

Animal Studies

Male SKH-1 mice weighing 25–30 g were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc., (Wilmington, MA). All mice were maintained and used in accordance with the animal protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University at Buffalo. A dose of 0.45 mg/kg of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW was administered to mice via penile vein injection or subcutaneous injection into the front footpad. Blood (1 mL samples) was obtained by cardiac puncture post-dose at 5 (only for IV administration), 15, 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 72 (3 days), 168 (7 days), and 288 h (12 days) and stored in heparin-containing tubes. Three animals were killed at each time point for collection of blood and lymph nodes including axillary, cervical, and inguinal lymph nodes. Plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation of blood samples at 4°C at 7,000 rpm for 5 min and stored at −20°C until being analyzed for drug concentration.

Plasma Concentrations Determined by Fluorescence Imaging

Plasma calibration standards were prepared by diluting bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate to concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 μg/mL using phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) and blank mouse plasma 50% v/v (Bioreclamation Inc, Hicksville, NY, USA). Quality control samples were also prepared in bulk, aliquoted, and then stored at −20°C until assayed. The standards or samples were loaded into 96-well plates, and wavelength-resolved fluorescence hyperspectral images were acquired with the Maestro imaging system (CRI). A near-infrared filter set with a 710 to 760 nm excitation filter and an 800 nm long-pass emission filter were used. A region of interest (ROI) was set on the whole well on the image. Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate fluorescence at ROI was quantified using the manufacturer’s software after spectrally unmixing the fluorescence spectrum with the autofluorescence spectrum of the blank plasma solution using linear least-square optimization. The standard curve was generated to convert average fluorescence intensity from the acquired images into bevacizumab concentrations (9).

Plasma and Lymph Node Concentrations Determined by ELISA

Plasma concentrations of bevacizumab were determined by a validated ELISA method using a human IgG ELISA kit (Bethyl laboratories, Inc, Montgomery, TX, USA). Plasma samples were diluted 10–100-fold with dilution buffer. ELISA plates, pre-coated with anti-human IgG antibody, were incubated with diluted plasma sample (100 μL/well) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with wash buffer, 100 μL of biotinylated anti-hIgG detection antibody was added and the samples incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After washing, strepavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase conjugate was added (100 μL/well) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. At the end of the incubation period, plates were washed again, followed by the addition of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution (100 μL/well). The color reaction was stopped by adding dilute sulfuric acid. The absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm using a SpectraMax 190 plate reader (molecular devices corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Axillary lymph nodes collected in the biodistribution study were homogenized in T-PER tissue protein extraction reagent (40:1, v/w (milliliter/gram tissue)) with 1 mM peptidase inhibitor, benzamidine hydrochloride hydrate, and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5 min to pellet cell/tissue debris. The supernatants were collected and diluted 0- to 40-fold with dilution buffer and analyzed by ELISA.

Noncompartmental Analysis

PK parameters of bevacizumab were estimated by noncompartmental analysis (NCA) using Phoenix WinNonlin 6.1 software (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA) with the Bailer method (for sacrificial sampling). Maximum concentration (Cmax) and time to Cmax (Tmax) were the observed values. AUC0 to infinity, the area under the mean concentration curve from the time of administration of the dose extrapolated to infinity, based on the last observed concentration, was calculated by the trapezoidal rule. The systemic clearance (CL), terminal slope λz, and mean residence time (MRT) were estimated using NCA, based on the PK profiles obtained with the ELISA assay. T1/2 was calculated as 0.693/λz. Bioavailability (BIO) was calculated as

Compartmental Analysis and Modeling

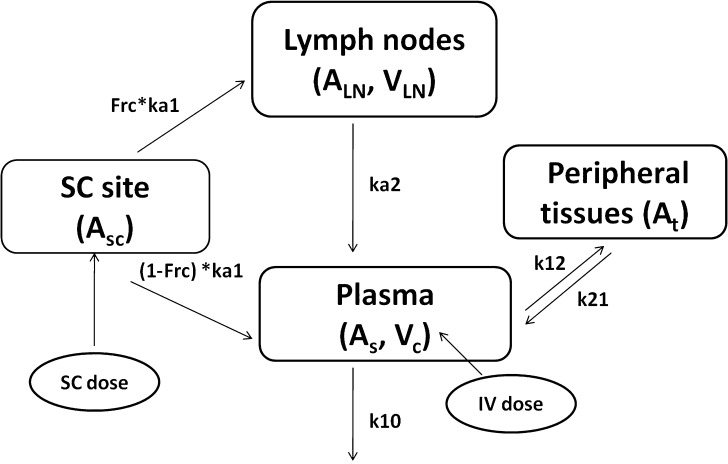

Plasma concentration-time data for the IV and SC doses were simultaneously fit to a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model with first-order absorption and elimination (Eqs. 1 and 2 for IV data and Eqs. 3 and 4 for SC data) (Fig. 1). Lymph node uptake data and loss from the subcutaneous compartment, after IV and SC administration, were described by Eqs. 5 and 6, respectively, and fit simultaneously with the plasma data. All concentrations used were determined by ELISA. After SC administration, proteins can enter the blood directly through the blood capillaries present in the SC tissue, or via the lymphatic vessels that drain into the bloodstream via the thoracic and other lymph ducts (10). Previously published models have been used to describe this absorption process after SC administration of the protein drugs leptin (10) and IL-10 (11). In our model, the fractions delivered by the lymphatic and systemic absorption processes were modeled as parameters Frc and (1-Frc), respectively. Parameters obtained directly by simultaneous fitting were Vc, k10, k12, k21, ka1, ka2, and Frc, where Vc is the volume of distribution for the central compartment. VLN is the volume of distribution for the lymph node compartment. k12 and k21 are the first-order rate constants for distribution to and from the peripheral compartment. k10 is the first-order elimination rate constant for bevacizumab from the central compartment. ka1 is the first-order absorption rate constant which includes two absorption processes, systemic absorption and lymphatic absorption. ka2 is the first-order rate constant describing transfer from the lymphatic system to plasma. BIO was fixed as 1 based on the NCA results, and volume of distribution for the lymph node compartment, VLN, was fixed as 0.33 mL/kg based on the actual weight of axillary lymph nodes (assuming 1 g/ml specific density) and the average weight of SKH-1 mice.

Fig. 1.

Proposed pharmacokinetic model for bevacizumab labeled with IR800CW to characterize its disposition after IV and SC administration. A is the amount of bevacizumab in various compartments in the model. Vc is the volume of distribution for the central compartment. V LN is the volume of distribution for the lymph node compartment. k 12 and k 21 are the first-order rate constants for distribution to and from the peripheral compartment. k 10 is the first-order elimination rate constant for bevacizumab from the central compartment. k a1 is the first-order absorption rate constant which includes two absorption processes, systemic absorption and lymphatic absorption. The fraction absorbed by the lymphatic compartment is given by Frc, and the fraction taken up by the blood capillaries is 1-Frc. ka2 is the first-order rate constant describing transfer from the lymphatic system to plasma

The differential equations used for the model were:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

where As,iv = Cs,iv × Vc, As,sc = Cs,sc × Vc, ALN,sc = CLN,sc × VLN

All terms are defined in the legend to Fig. 1.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Characterization of Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW Conjugates

In our study, we employed IRDye 800CW which bears an NHS ester reactive group that could be coupled to the primary amines of bevacizumab, forming a stable bioconjugate. The D/P ratios of IRDye 800CW to bevacizumab were estimated to be 3.5:1 when the reaction molar ratios of IRDye 800CW to bevacizumab were 12:1. The final concentration of bevacizumab was measured as 0.94 mg/mL, which is close to the original concentration of protein (1 mg/mL) used in the synthesis reaction, indicating that the conjugate purification process did not result in significant removal of protein.

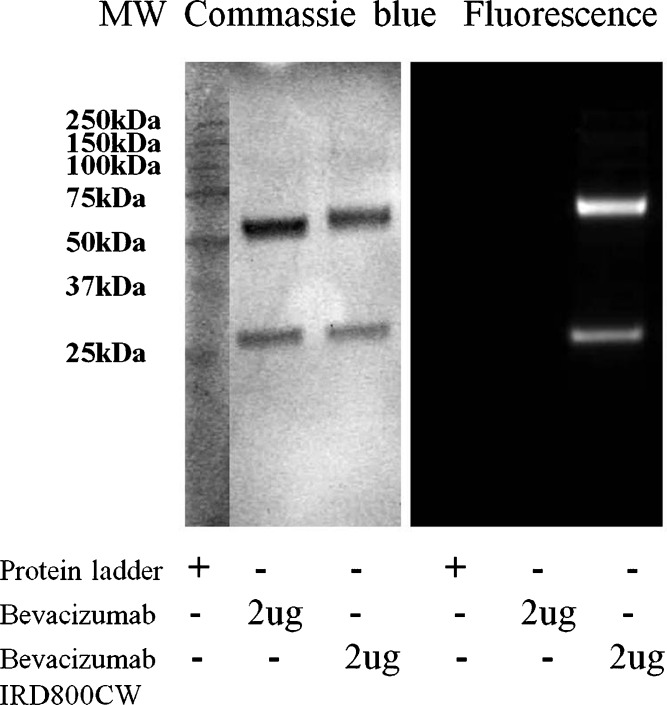

Following purification, the IRDye800CW-conjugated bevacizumab was subjected to SDS-PAGE to confirm the conjugation of dye with bevacizumab. Prior to Coomassie blue staining, the gel was illuminated using a near-infrared filter set to detect any fluorescence arising from IRDye 800CW conjugated bevacizumab bands. As shown in Fig. 2, two clear single bands of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate were detected by both fluorescence imaging (Fig. 2, right panel) and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2, left panel), while the two bands of bevacizumab standard were only visible by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2, left panel). Antibodies under reduced SDS-PAGE conditions produce heavy chains and light chains since the disulphide bonds are cleaved following treatment with reducing reagents (12). Therefore, the two bands shown in each column on the left panel of Fig. 2 correspond to the heavy chains (∼50 kDa) and light chains (∼25 kDa) of bevacizumab. The SDS-PAGE results indicated that bevacizumab was successfully conjugated with IRDye 800CW without any degradation.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of bevacizumab and bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), with detection by both Coomassie blue staining (left panel) and fluorescence imaging (right panel)

In Vitro Stability of Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW Conjugate in Plasma and Lymph Node Homogenates

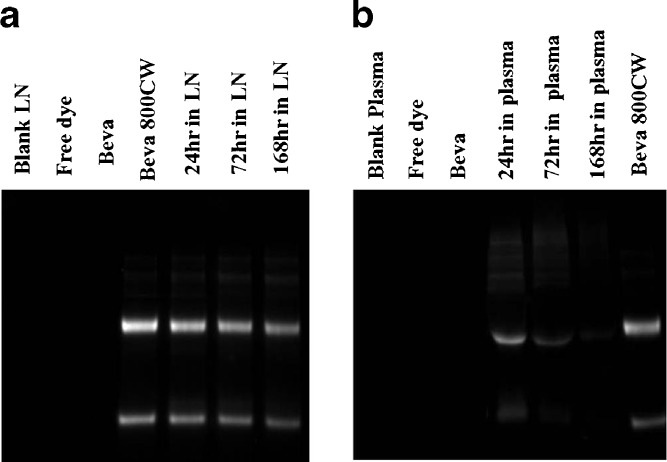

Electrophoretic analysis of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate in lymph node homogenate (Fig. 3a) revealed that bevacizumab was mainly present as two bands (heavy and light chains) as long as 7 days. Degradation products of lower molecular weight were minimal. Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) was used to quantitatively measure the mean fluorescence intensity of the dominant bands of 2 μg of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW shown on the fluorescence image of the gel. The mean fluorescence intensity of the heavy-chain band of bevacizumab–IRDye conjugate in lymph node homogenate after incubation for 24 h was 81.8% of the bevacizumab original standard sample. Studies using SE-HPLC indicated no presence of a free dye peak or lower molecular weight conjugates. This suggested that the bevacizumab remained largely intact. Similar results were observed following the incubation of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW in mouse plasma (Fig. 3b), with 79.2% of the fluorescent signal in the original sample present at 24 h.

Fig. 3.

a SDS-PAGE of blank LN homogenate, free dye, bevacizumab in PBS (2 μg), bevacizumab–800CW conjugate (2 μg) in PBS and bevacizumab–800CW conjugate (2 μg) spiked in blank mouse lymph node homogenate after incubation at 37°C for 24 h, 3, and 7 days, detected by fluorescence imaging. b SDS-PAGE of blank plasma, free dye, bevacizumab in PBS (2 μg), and bevacizumab–IRDye800CW conjugate (2 μg) spiked in blank mouse plasma after incubation at 37°C for 24 h, 3, and 7 days as well as standard bevacizumab–800CW conjugate (2 μg) in PBS, detected by fluorescence imaging

Fluorescence Imaging of Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW Conjugate

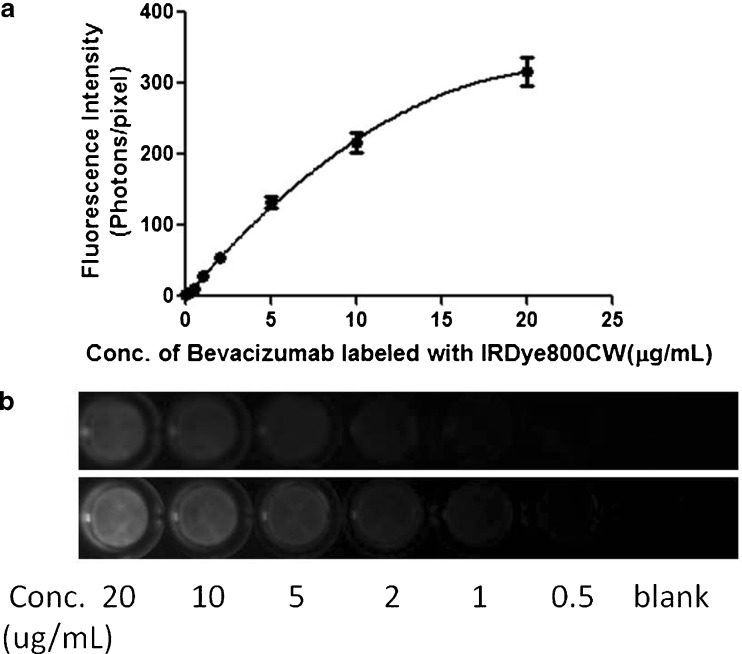

The best-fit line for the calibration curve of bevacizumab–IRDye conjugate to convert fluorescence intensity to bevacizumab concentration was obtained by fitting the data to a quadratic equation;  (Fig. 4a). Correlation coefficients (R2) of at least 0.99 were obtained for the intra-day and inter-day validation. Using our experimental conditions, the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was 0.5 μg/mL in plasma. The intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy values of QC samples, evaluated in plasma, are presented in the Electronic supplementary materials. Based on the results for the low (1 μg/mL), medium (5 μg/mL), and high (10 μg/mL) concentration QC samples, the intra-day precision and accuracy of the assay ranged from 3.68% to 6.16% and 99.9–109%, respectively. The inter-day precision and accuracy were within 5.67–15% and 102–107%. The working range of the assay was 0.5–20 μg/mL. Figure 4b presents the fluorescence images (top image) and spectrally unmixed images (bottom image) of a 96-well plate loaded with plasma spiked with bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW standards. It shows that the fluorescence intensity increased with increasing concentrations of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW.

(Fig. 4a). Correlation coefficients (R2) of at least 0.99 were obtained for the intra-day and inter-day validation. Using our experimental conditions, the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was 0.5 μg/mL in plasma. The intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy values of QC samples, evaluated in plasma, are presented in the Electronic supplementary materials. Based on the results for the low (1 μg/mL), medium (5 μg/mL), and high (10 μg/mL) concentration QC samples, the intra-day precision and accuracy of the assay ranged from 3.68% to 6.16% and 99.9–109%, respectively. The inter-day precision and accuracy were within 5.67–15% and 102–107%. The working range of the assay was 0.5–20 μg/mL. Figure 4b presents the fluorescence images (top image) and spectrally unmixed images (bottom image) of a 96-well plate loaded with plasma spiked with bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW standards. It shows that the fluorescence intensity increased with increasing concentrations of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW.

Fig. 4.

a Representative standard curve to convert fluorescence intensity of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate to bevacizumab concentration derived from the fluorescence image of the plasma spiked with bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW standards. Solid circles show bevacizumab concentration in plasma against the average calibrated and spectrally unmixed fluorescence determined from the fluorescence image. The standard curve is over the range of 0.5–20 μg/mL. The curve is fitted with a quadratic equation, and R 2 = 0.9992. Error bars represent the standard deviation across the mean of three replicates. b Color fluorescence (top image) and spectrally unmixed fluorescence (bottom image) images of a 96-well plate loaded with plasma spiked with bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW standards

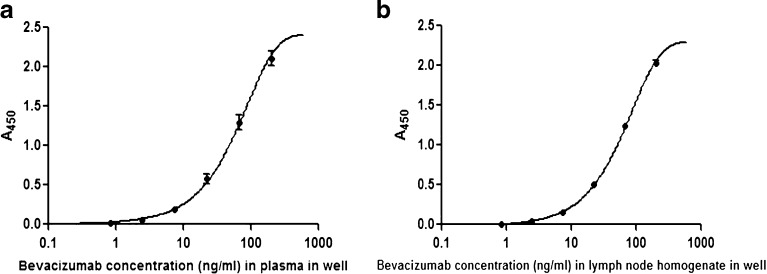

ELISA of Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW Conjugates

To validate the plasma concentrations measured by fluorescence imaging, plasma bevacizumab concentrations were also quantified using ELISA. The typical calibration curves of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate in plasma as well as in lymph node homogenate are shown in Fig. 5a, b. These two calibration curves were best fit with a four-parameter logistic equation. The assay range was 0.82 to 200 ng/mL for bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate in plasma and lymph node homogenate.

Fig. 5.

Representative ELISA calibration curve of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye800CW in mouse plasma (a) and in mouse lymph node homogenate (b)

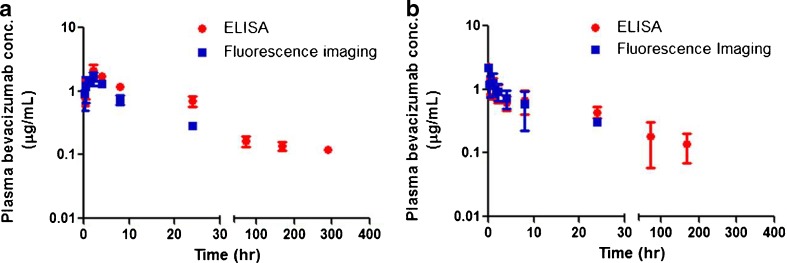

Pharmacokinetics of Bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW Conjugates in SKH-1 Mice

Bevacizumab concentration-time profiles in plasma after SC or IV administration of 0.45 mg/kg (the equivalent amount of injected dye is 10.5 nmol/kg) of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugates are presented in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. Note that the dose of antibody used in this study was restricted by the protein–dye conjugation process and the volume of SC injection. With SC injection into the front footpad in the mouse, the maximal volume of injection was 15 μL, resulting in an injected dose of 0.45 mg/kg. The fluorescence imaging measurements and ELISA measurements correlated well, showing that the fluorescence intensity of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate corresponds to bevacizumab concentrations in mouse plasma samples. Due to the high sensitivity of the ELISA method, the concentration of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW could be measured until the end of sampling at 12 days (288 h) after SC administration. Table I lists the Tmax, Cmax, λz, CL, and MRT parameter values obtained by NCA. After SC administration, the Tmax was 2 h and the peak concentration of bevacizumab–800CW conjugate was less than that after IV administration of a similar dose. After an IV dose of approximately 0.45 mg/kg in mice, the clearance was 6.96 mL/h/kg. The half life of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW was 4.6 days after SC administration and 3.9 days after IV administration. In our mouse model, complete bioavailability was estimated after SC administration.

Fig. 6.

Plasma concentrations of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW after SC (a) and IV (b) administration of 0.45 mg/kg doses in SKH-1 mice. Concentrations were determined by fluorescence and ELISA measurements. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3

Table I.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Bevacizumab 800CW After IV and SC Administration of 0.45 mg/kg of Bevacizumab 800CW (Three Animals per Group)

| Parameters | T max (h) | C max (μg/mL) | AUC0 to infinity (h μg/mL) | λz (1/h) | CL (mL/h/kg) | T 1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 2.00 | 2.10 ± 0.291 | 91.4 | 0.00625 | – | 111 h (4.6 day) |

| IV | 2.31 ± 0.145 | 64.7 | 0.00739 | 6.96 | 93.8 h (3.9 day) |

Cmax maximum observed concentration, Tmax time to Cmax, AUC 0 to infinity the area under the mean concentration-time curve, λz terminal slope, CL plasma clearance, T 1/2 half life, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous

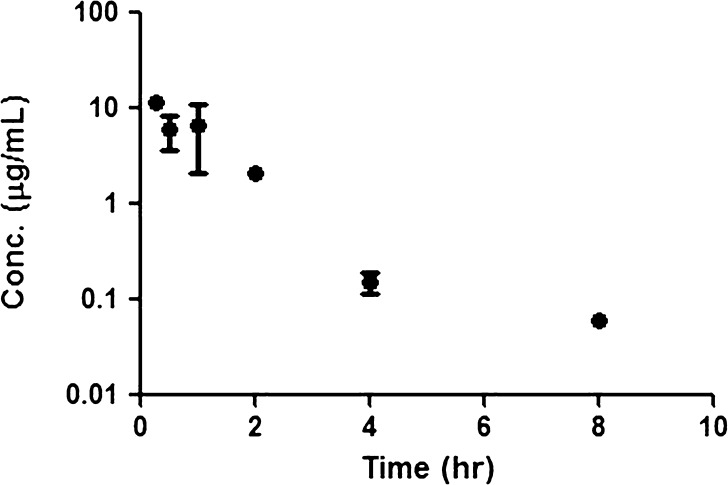

In our fluorescence imaging study, we found that only axillary lymph nodes on the injection side showed fluorescence signals after SC administration of bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate. The concentration of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW in the axillary lymph nodes after SC administration was determined by ELISA, and Fig. 7 shows the concentration versus time plot. Due to the small weight of axillary lymph nodes and the required volume of samples for ELISA measurements, the dilution ratios for axillary lymph node homogenates are high (40:1). This might be one of the reasons that we could not measure the concentration of bevacizumab in lymph node samples after 8 h. Also, for our 8-h time points, only one out of three samples had detectable concentrations. NCA using the Bailer method (for sacrificial sampling) was performed to determine the area under the amount of dye conjugate in the axillary lymph node versus time plot, obtained after SC administration. On the other hand, after IV administration, the accumulation of bevacizumab–IRDye800CW in the lymph node pool including axillary, cervical, and inguinal lymph nodes was negligible, as determined by ELISA.

Fig. 7.

Concentrations of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW in axillary lymph nodes after SC administration of 0.45 mg/kg doses in SKH-1 mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3, except for the 8-h time points, where concentrations could only be quantitated in one out of three samples

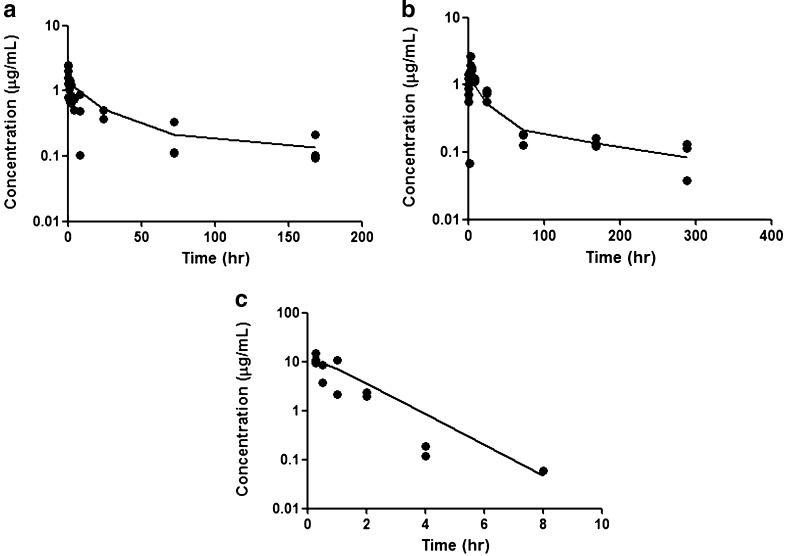

For the compartmental analysis, a two-compartment model was the most appropriate model to describe the disposition of bevacizumab after IV administration (Fig. 8a). After IV and SC dosing, the plasma concentrations were simultaneously fitted to a two-compartment model with first-order input and elimination (Fig. 8b). Volume of distribution (Vc) and rate constants (k12, k21, and k10) were estimated after simultaneous fitting for plasma profiles after IV and SC administration and are shown in Table II. Plasma and axillary lymph node profiles after SC administration were simultaneously modeled using first-order differential equations to describe the absorption into the blood and draining lymph nodes (Fig. 8c). The absorption rate constant (ka) after SC administration was 4.82 h−1 (Table II). The fraction of the absorbed dose taken up via lymph was estimated at about 1%, which is consistent with the non-compartmental calculation based on the ELISA measurements for bevacizumab in the axillary lymph nodes homogenate after collecting axillary lymph node following SC administration (0.85%). For that estimate, amount was determined by the area under the amount–time curve × k in the lymph nodes, assuming rapid absorption from the SC site into the lymph nodes.

Fig. 8.

a Plasma concentration-time data after IV administration of 0.45 mg/kg bevacizumab–IRDye 800. b Plasma concentration-time data after SC administration of 0.45 mg/kg bevacizumab–IRDye 800. c LN concentration-time data after SC administration of 0.45 mg/kg bevacizumab–IRDye 800. The solid lines represent the model-fitted lines, based on the PK model

Table II.

PK Parameter Estimates for Bevacizumab 800CW After IV and SC Administration (0.45 mg/kg) to Mice

| Parameter | Mean | CV% |

|---|---|---|

| Vc (mL/kg) | 319 | 9.59 |

| k12 (h−1) | 0.0314 | 40.1 |

| k21 (h−1) | 0.0131 | 57.0 |

| k10 (h−1) | 0.0162 | 24.5 |

| VLN (mL/kg) | 0.33 (Fixed) | |

| BIO | 1(Fixed) | |

| ka1 (h−1) | 4.82 | 40.9 |

| ka2 (h−1) | 0.723 | 9.64 |

| Frc | 0.00964 | 19.6 |

PK pharmacokinetics, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous

DISCUSSION

Fluorescence probes such as dyes or quantum dots have been used to label the protein or drugs and track their uptake via microscopy or in vivo imaging (13–16). Non-invasive fluorescence imaging has been used for kinetic analysis for the determination of receptor densities (17,18), or detection of tumors (19–22) or lymphatic uptake (20,23). For example, Chernomordik et al. (17) used HER2-specific affibody molecules labeled with Alexa Fluor 750 to characterize HER2 expression from non-invasive optical imaging data. The compartmental ligand–receptor model was used to calculate HER2 expression and revealed a good correlation between the estimated parameter and HER2 amplification/over-expression in tumor cells (17). Similarly, Alexa Fluor 680–bevacizumab (Alexa680–bevacizumab) was prepared for imaging VEGF expression in tumors (9). Although the tumor uptake or lymphatic uptake of fluorescent antibodies has been evaluated by non-invasive fluorescence imaging, there are few reports examining the PK properties for fluorescent antibodies.

In this study, we used IRDye 800CW, a near-IR fluorescent dye with absorbance maximum at 774 nm and emission maximum at 789 nm. Bevacizumab was conjugated with IRDye 800CW and used to determine the plasma concentrations and lymphatic uptake in SKH-1 mice after SC and IV administration. To confirm our results, we used ELISA to measure the concentrations of bevacizumab in mouse plasma and lymph node homogenates. As shown in Fig. 6, the PK profiles of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW, measured by both fluorescence imaging and ELISA, correlated well within 24 h after IV or SC administration of the conjugate; fluorescence could not be quantitated after 24 h. SDS-PAGE results demonstrated that the fluorescent tag remained attached to bevacizumab in plasma and lymph node homogenates. There were minimal degradation products of lower molecular weights after incubation of bevacizumab in lymph node homogenate for 24 h, indicating bevacizumab was transported through lymphatics in intact form. Similarly, using SDS-PAGE, Lin et al. (24) also found that no metabolites were present in lymph node homogenate after administration of 125I-rhuMAb VEGF. Therefore, there appears to be minimal catabolism of bevacizumab in the draining lymph nodes. Additionally, the successful application of ELISA for the fluorescent antibody conjugate also revealed that the activity of bevacizumab was retained after dye conjugation. The lack of detection of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW by fluorescence imaging at later times is likely due to the relatively high LLOQ of the method (0.5 μg/mL).

Following a dose of 0.45 mg/kg bevacizumab IV to SKH-1 mice, we determined a clearance of 6.96 ml/h/kg (166 ml/day/kg) and a half life of 3.9 days. Shah et al. (25) administered an IV dose of 5 mg/kg in athymic nude mice and reported an elimination clearance of 6.27 ml/day/kg with a half life of about 5.5 days. Another report on the IV administration of a dose of 9.3 mg/kg of 125I-rhuMab VEGF in female nude mice reported a clearance of 15.7 ml/day/kg or 0.65 ml/h/kg and a half life of 6.8 days (24). Therefore, while bevacizumab does not bind to murine VEGF-A and so would not be expected to undergo target-mediated elimination, it appears that its clearance may be dose-dependent. Complete bioavailability (100%) of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW was observed in our study after SC administration. Our findings of complete bioavailability in mice are consistent with the report of complete bioavailability after SC administration of rhuMab VEGF (9.3 mg/kg) in mice (24). However, due to the potential dose-dependent clearance of bevacizumab, this is only an estimate since there may be differences in clearance between IV and SC, and this might be responsible for the higher AUC seen after SC administration of bevacizumab, compared with that after IV administration. The excellent bioavailability of bevacizumab after SC administration suggests that SC administration may represent an alternative route of administration for bevacizumab. However, due to species differences in the lymphatic uptake and bioavailability of monoclonal antibodies, confirmation is needed in clinical studies.

Compared with IV administration, a significantly higher uptake by the lymphatics was observed after SC administration, which is consistent with our previous report examining another protein, VEGF-C 156S (26). Lymph node uptake data and blood sampling after IV and SC administration allowed the estimation of the absorption rate constant (ka1) and the fraction of the absorption through lymph (Frc) and blood (1-Frc), based on fitting to a PK model. From the model fitting, the fraction of bevacizumab absorbed through lymph compartment after SC administration of bevacizumab, based on the draining lymph node uptake, is low (around 1%). To our knowledge, this represents the only data for the lymphatic uptake of bevacizumab in any animal species. However, the estimated absorption fraction through lymph after SC administration of bevacizumab using the mouse model is lower than that estimated for a variety of proteins using a sheep model, where 50% of a subcutaneous dose was taken up by the peripheral lymphatics for macromolecules with MWs over 16 kDa (6,27). Our estimate may represent an underestimate of the extent of lymphatic absorption, if any of the lymph vessels draining the SC site of injection bypass the lymph nodes. Although this remains a possibility, generally for lymph nodes present in the periphery, such as the axillary lymph nodes that drain the front forearm in the mouse, afferent lymph vessels will empty lymph into the marginal sinus of the lymph nodes and efferent lymph vessels will carry lymph away from the nodes (28,29). Additionally, our finding of limited uptake of proteins by the lymphatic system in the mouse is consistent with reported data for bovine serum albumin in our mouse model (30) and for lymphatic uptake in the rat (7,8). Very little lymphatic uptake of proteins (less than 3%) was reported in a rat model following SC administration of proteins, when thoracic lymph sampling was used to determine lymphatic uptake (7,8). The reasons underlying these potential differences between rodents and sheep are unknown, but may be attributed to differences in species, injection site, sampling method, or the model proteins used, among others.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this is the first report characterizing the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and lymphatic absorption of near-infrared dye-labeled antibody conjugate after SC and IV administration. A rapid fluorescence imaging method with high precision and accuracy for the determination of bevacizumab labeled with IRDye 800CW in mouse plasma has been developed. The assay was successfully applied to study the bevacizumab–IRDye 800CW conjugate pharmacokinetics after IV and SC administration in mice. A sensitive ELISA method was also developed to validate the PK results obtained by fluorescence imaging. After SC administration, bevacizumab–IRDye800CW was present in the axillary lymph nodes that drain the SC site, mainly in an intact form for at least 24 h, and the antibody exhibited complete bioavailability. Lymph node concentrations were higher after SC administration compared with IV administration: Higher lymphatic exposure after SC administration allows targeting of biotherapeutics to the lymphatic system for the treatment of lymphatic diseases such as lymphedema, as well as for the treatment of metastatic cancer in the lymphatic system. A mechanistic PK model was used for simultaneously fitting plasma and lymphatic concentration-time data and for estimating the extent of lymphatic absorption after SC administration of bevacizumab; this model will be useful in evaluations of the subcutaneous tissue absorption and bioavailability of antibodies and other macromolecules.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 12 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the University at Buffalo Center for Protein Therapeutics to MEM. The authors thank Dr. E.J. Bergey and Dr. P.N. Prasad of the Institute for Lasers, Photonics and Biophotonics, University at Buffalo, for use of the Maestro imaging system and their expertise with fluorescence imaging.

References

- 1.Presta LG, Chen H, O’Connor SJ, Chisholm V, Meng YG, Krummen L, Winkler M, Ferrara N. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 1997;57(20):4593–4599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(5):391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MH, Gootenberg J, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: bevacizumab (Avastin(R)) plus carboplatin and paclitaxel as first-line treatment of advanced/metastatic recurrent nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12(6):713–718. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-6-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MH, Shen YL, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: bevacizumab (Avastin) as treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Oncologist. 2009;14(11):1131–1138. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(5):548–558. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Supersaxo A, Hein WR, Steffen H. Effect of molecular weight on the lymphatic absorption of water-soluble compounds following subcutaneous administration. Pharm Res. 1990;7(2):167–169. doi: 10.1023/A:1015880819328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagan L, Gershkovich P, Mendelman A, Amsili S, Ezov N, Hoffman A. The role of the lymphatic system in subcutaneous absorption of macromolecules in the rat model. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;67(3):759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kojima K, Takahashi T, Nakanishi Y. Lymphatic transport of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor in rats. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1988;11(10):700–706. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.11.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang SK, Rizvi I, Solban N, Hasan T. In vivo optical molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor for monitoring cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4146–4153. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLennan DN, Porter CJ, Edwards GA, Brumm M, Martin SW, Charman SA. Pharmacokinetic model to describe the lymphatic absorption of r-metHu-leptin after subcutaneous injection to sheep. Pharm Res. 2003;20(8):1156–1162. doi: 10.1023/A:1025036611949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radwanski E, Chakraborty A, Van Wart S, Huhn RD, Cutler DL, Affrime MB, et al. Pharmacokinetics and leukocyte responses of recombinant human interleukin-10. Pharm Res. 1998;15(12):1895–1901. doi: 10.1023/A:1011918425629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gearing AJH, Thorpe SJ, Miller K, Mangan M, Varley PG, Dudgeon T, et al. Selective cleavage of human IgG by the matrix metalloproteinases, matrilysin and stromelysin. Immunol Lett. 2002;81(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(01)00333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phelps MA, Foraker AB, Gao W, Dalton JT, Swaan PW. A novel rhodamine-riboflavin conjugate probe exhibits distinct fluorescence resonance energy transfer that enables riboflavin trafficking and subcellular localization studies. Mol Pharm. 2004;1(4):257–266. doi: 10.1021/mp0499510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu F, Wuensch SA, Azadniv M, Ebrahimkhani MR, Crispe IN. Galactosylated LDL nanoparticles: a novel targeting delivery system to deliver antigen to macrophages and enhance antigen specific T cell responses. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(5):1506–1517. doi: 10.1021/mp900081y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu G, Yong KT, Roy I, Mahajan SD, Ding H, Schwartz SA, et al. Bioconjugated quantum rods as targeted probes for efficient transmigration across an in vitro blood–brain barrier. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19(6):1179–1185. doi: 10.1021/bc700477u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yong KT, Ding H, Roy I, Law WC, Bergey EJ, Maitra A, et al. Imaging pancreatic cancer using bioconjugated InP quantum dots. ACS Nano. 2009;3(3):502–510. doi: 10.1021/nn8008933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chernomordik V, Hassan M, Lee SB, Zielinski R, Gandjbakhche A, Capala J. Quantitative analysis of Her2 receptor expression in vivo by near-infrared optical imaging. Mol Imaging. 2010;9(4):192–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SB, Hassan M, Fisher R, Chertov O, Chernomordik V, Kramer-Marek G, et al. Affibody molecules for in vivo characterization of HER2-positive tumors by near-infrared imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(12):3840–3849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biffi S, Garrovo C, Macor P, Tripodo C, Zorzet S, Secco E, et al. In vivo biodistribution and lifetime analysis of cy5.5-conjugated rituximab in mice bearing lymphoid tumor xenograft using time-domain near-infrared optical imaging. Mol Imaging. 2008;7(6):272–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding H, Yong KT, Law WC, Roy I, Hu R, Wu F, et al. Non-invasive tumor detection in small animals using novel functional Pluronic nanomicelles conjugated with anti-mesothelin antibody. Nanoscale. 2011;3(4):1813–1822. doi: 10.1039/c1nr00001b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J, Yong KT, Roy I, Hu R, Ding H, Zhao L, et al. Additive controlled synthesis of gold nanorods (GNRs) for two-photon luminescence imaging of cancer cells. Nanotechnology. 2010;21(28):285106. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/28/285106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopwitthaya A, Yong KT, Hu R, Roy I, Ding H, Vathy LA, et al. Biocompatible PEGylated gold nanorods as colored contrast agents for targeted in vivo cancer applications. Nanotechnology. 2010;21(31):315101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/31/315101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Licha K, Debus N, Emig-Vollmer S, Hofmann B, Hasbach M, Stibenz D, et al. Optical molecular imaging of lymph nodes using a targeted vascular contrast agent. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10(4):41205. doi: 10.1117/1.2007967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YS, Nguyen C, Mendoza JL, Escandon E, Fei D, Meng YG, et al. Preclinical pharmacokinetics, interspecies scaling, and tissue distribution of a humanized monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288(1):371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah DK, Veith J, Bernacki RJ, Balthasar JP. Evaluation of combined bevacizumab and intraperitoneal carboplatin or paclitaxel therapy in a mouse model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68(4):951–958. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhansali SG, Balu-Iyer SV, Morris ME. Influence of route of administration and liposomal encapsulation on blood and lymph node exposure to the protein VEGF-C156S. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(2):852–859. doi: 10.1002/jps.22795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter CJ, Charman SA. Lymphatic transport of proteins after subcutaneous administration. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89(3):297–310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6017(200003)89:3<297::AID-JPS2>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engeset A. The route of peripheral lymph to the blood stream; an X-ray study of the barrier theory. J Anat. 1959;93(1):96–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kubik S. Anatomy of the lymphatic system. In: Foldi M, Foldi E, Kubik S, editors. Textbook of lymphology. San Francisco: Elsevier GmbH; 2003. pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu F, Bhansali SG, Tamhane M, Kumar R, Vathy LA, Ding H, et al. Noninvasive real-time fluorescence imaging of the lymphatic uptake of BSA–IRDye 680 conjugate administered subcutaneously in mice. J Pharm Sci. 2012. doi:10.1002/jps.23058. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 12 kb)