Abstract

Background

The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer can result in an array of late cancer-specific side effects and changes in general well-being. Research has focused on Caucasian samples, limiting our understanding of the unique health-related quality of life outcomes of African American breast cancer survivors (BCS). Even when African American BCS have been targeted, research is limited by small samples and failure to include comparisons of peers without a history of breast cancer.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to compare health-related quality of life of African American women BCS to African American women with no history of breast cancer (control group).

Methods

A total of 140 women (62 BCS and 78 control), ages 18 years or older and 2–10 years post-diagnosis, was recruited from a breast cancer clinic and cancer support groups. Participants provided informed consent and completed a one-time survey based on Brenner’s (1995) proximal-distal health-related quality of life model.

Results

After adjusting for age, education, income, and body mass index, African American BCS experienced more fatigue (p=0.001), worse hot flashes (p<0.001) and worse sleep quality (p<0.001), but more social support from their partner (p=0.028) and more positive change (p=0.001) compared to African American women controls.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that African American women BCS may experience unique health-related outcomes that transcend age, education, socio-economic status and body mass index.

Implications for Practice

Findings suggest the importance of understanding the survivorship experience for particular racial and ethnic subgroups to proactively assess difficulties and plan interventions.

Keywords: Health-related Quality of Life, African Americans, Female, Survivors, Breast Neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

African American BCS may experience an array of late cancer-specific side effects, disruption in general physical and mental functioning, fluctuating affective states, and changes in life satisfaction. In a previous comprehensive review of the literature, findings from 26 qualitative and quantitative descriptive studies were synthesized to summarize what is known regarding the health-related quality of life of African American BCS.1 Based on this review, some consistent patterns in quality of life deficits were noted (e.g., treatment-related physical symptom distress), as well as favorable aspects of quality of life that occurred toward the distal end of the health-related quality of life continuum (e.g., heightened spirituality, positive growth, and overall well-being) when comparing African American BCS to survivors of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. This work demonstrated the importance of evaluating health-related quality of life outcomes across a continuum from proximal (disease-specific functioning) to global (overall well-being). A limitation noted in the existing literature was that most studies did not include a race-matched comparison group of women without breast cancer. Some studies did not include any comparison group and others used non-African American women for comparison. Because African American women without cancer represent the strongest comparison group for African American women with breast cancer, it is important to compare health-related quality of life in these two groups.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether health-related quality of life differed between African American women with and without a history of breast cancer. The specific aim was to compare African American breast cancer survivors (BCS) to African American women with no history of breast cancer on disease-specific, generic, and global quality of life measures. Based on previous research,1 the study hypothesis was that African American BCS would have greater psychological and physical functioning concerns, but similar generic and global well-being relative to African American women with no history of breast cancer.

Theoretical framework

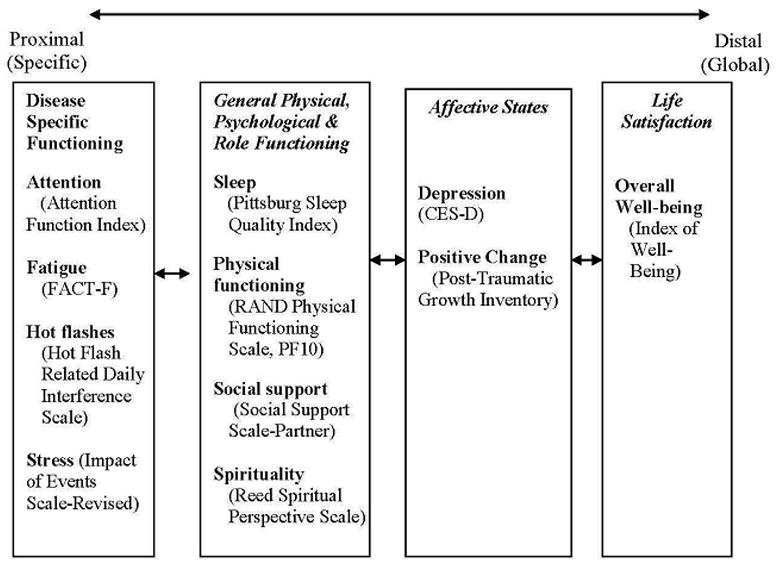

Brenner and colleagues’ proximal-distal approach to conceptualizing multiple health-related quality of life outcomes2 was used to guide the study (Figure). This model proposes that health-related quality of life outcomes exist on a continuum of interrelated domains extending from proximal (i.e., disease-specific functioning) to distal (i.e., global well-being). The domains of disease-specific functioning; general physical, psychological, and role functioning; affective states; and life satisfaction were examined. These domains, although conceptualized separately, are interrelated, and as a result, survivors may have health-related quality of life concerns in more than one domain. The domain “disease-specific functioning” consists of the more direct effects of the disease and its treatment, typically on outcomes directly influenced by physical and mental changes (e.g., attention, fatigue, hot flashes, and event (breast cancer)-related stress. The “general physical, psychological, and role functioning” domain involves more general outcomes that tend to be affected by the more specific proximal changes or their implications. Therefore, this domain includes general physical, psychological, and coping factors requisite to perform activities of daily living. Outcomes at this level might include, for example, sleep and overall physical functioning, as well as resources such as satisfaction with partner social support and spirituality. The most distal domains in the continuum are “affective states” and “life satisfaction.” Affective states include factors associated with emotional and psychological states (e.g., depressive symptoms and positive change), and life satisfaction refers to global well-being (i.e., overall well-being). Only the more distal levels correspond to quality of life as historically conceptualized, but many investigators agree that outcomes should be measured at multiple levels in order to best understand the impact of disease and treatment.3–5

Figure 1.

Study framework and measures: Proximal-distal framework adapted from Brenner et al.1 with corresponding variables and measures under each domain.

A two-step approach was used to identify important proxy variables for each domain of Brenner’s model. First, a comprehensive review of the literature was conducted to examine quality of life issues for African American breast cancer survivors.1 Important factors from this review were identified. Second, focus groups were conducted with African American BCS (description of the procedure in Kooken et al.6) to identify and/or confirm variables of importance and select specific measures.

METHODS

Design

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study using self-reported survey data to compare health-related quality of life between African American BCS and healthy African American women.

Sample

A convenience sample of female BCS was recruited by staff from university cancer center clinics, cancer center medical record review, and self-referral. Inclusion criteria and rationale included: (a) non-Hispanic African American women who were two to ten years post-diagnosis for non-metastatic breast cancer (Stage 0 to IIIB) (to identify late and long-term effects of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment); (b) age 18 years or older (to increase homogeneity of the sample); and (c) able to read and understand English (to ensure ability to complete selected instruments). The healthy African American comparison women were also aged 18 or over and able to read and understand English and had no personal history of breast cancer.

Procedure

Breast cancer survivors who were seen in the clinics, interested in the study, and gave their permission were contacted by the research staff. After determining eligibility, a research assistant obtained consent and distributed the paper survey packet. Participants completed the self-administered questionnaires and returned them in a self-addressed stamped envelope. To assure an adequate sample, eligible participants were also recruited through community events (breast cancer support groups and fundraisers). These women were mailed an introductory letter with information about the objectives of the study, instructions for completing the questionnaires, consent form, survey packet, and a stamped envelope to return study materials. The standardized instructions for completing the questionnaires included the length of time the participant should consider for each of the variables of interest and, therefore, were intended to ensure the accurate completion of the instruments.

Women for the comparison group were recruited through the same community advertisements and events (e.g., community events sponsored by the Black Nurses Association). These women were given or mailed the consent form, survey packet with instructions, and stamped envelope to return completed study materials.

All study participants received a $25 gift certificate upon return of the completed survey. The study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board. All women provided written informed consent and authorization to use their health information.

Study Variables and Measures

Study measures were selected based on Brenner et al.’s 2 conceptual model, a review of literature, and focus groups as described above (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Instruments are listed in Table 1, with number of items, possible score ranges, and alphas in the present study. Standard administration instructions and scoring for all scales was used as described by the original scale developers or prior literature. Since there were only minimal differences in internal consistency reliabilities of the measures between the two groups, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are reported for the combined samples. This information is important as it adds to the literature regarding the reliability of the instruments in a larger sample of African American women.

Table 1.

Scale Descriptions and Health Outcome Variables

| Scale Name and Source | No. of items | Possible Score | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-Specific Functioning | |||

| Attention (Attention Function Index) | 16 | 0–10 | 0.90 |

| Fatigue (FACT-F) | 13 | 0–42 | 0.91 |

| Hot Flashes (Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale) | 9 | 0–88 | 0.95 |

| Stress (Impact of Events Scale-Revised) | 20 | 0–80 | 0.94 |

| General Physical and Mental Functioning & Role Performance | |||

| Sleep (Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) | 7 | 0–21 | 0.75 |

| Physical Functioning (RAND Physical Function, PF 10) | 10 | 0–100 | 0.92 |

| Partner Social Support (Northouse Social Support Scale) | 7 | 7–35 | 0.83 |

| Spirituality (REED Spirituality Scales) | 10 | 1–6 | 0.94 |

| Affective State | |||

| Depression (CES-D) | 20 | 0–60 | 0.88 |

| Positive Change (Posttraumatic Growth Inventory) 21 | 21 | 0–105 | 0.97 |

| Life Satisfaction | |||

| Overall Well-being (Index of Well-being) | 9 | 9–63 | 0.93 |

Demographic, Medical, and Treatment-related Factors

Demographic, medical, and treatment-related factors were collected on an investigator-developed form. Self-reported demographics included age, education, marital status, income, and health insurance provider information. Medical and treatment-related variables included body mass index (BMI), time since diagnosis, stage, type of surgery, and type of adjuvant therapy. These data were self-reported and validated through medical records review by trained study staff.

DISEASE-SPECIFIC FUNCTIONING SCALES

Attention

The attention domain of cognitive functioning was measured with the Attention Function Index.7 Items assess functioning in following through on plans, finishing projects, and planning daily activities. A 10-point response scale (0=not at all to 10=extremely well) was adapted from the original linear visual analogue scale (100mm). Scale items were averaged to compute a mean scale score, with higher scores indicating better attention. This instrument has been used in healthy samples and a variety of cancer patient populations, including breast cancer patients.8, 9 Convergent validity has been demonstrated through statistically significant correlations with the concentration item from the Symptom Distress Scale and with the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (r = −0.58 and −0.60), respectively. Divergent validity was established with the Profile of Mood States-Confusion subscale (r = −0.59).9

Fatigue

Fatigue was measured with the FACT-F,10 which assesses symptoms of fatigue during the past 4 weeks. The scale uses a 5-point response scale of perceived severity (0=not at all, 4=very much), with higher total scores indicating greater fatigue. This instrument was designed and validated for cancer patients and has shown strong test-retest consistency (0.90) and internal consistency (0.95).11 Convergent validity has been demonstrated through high correlations with the Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS) and Profile of Mood States-Fatigue Subscale (r = 0.77 and 0.83, respectively).11

Hot flashes

The Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale (HFRDIS)12 was used to measure the degree that hot flashes interfered with nine daily life activities, including work, social activities, leisure activities, sleep, mood, concentration, relations with others, sexuality, and enjoyment of life, during the previous week. Respondents rate the level of interference based on their experience over the last 4 weeks, and response items for each activity range from 0 (did not interfere) to 10 (interfered a lot), with higher scores indicating more interference. The HFRDIS has demonstrated strong internal consistency (0.96), and it correlates significantly with other hot flash instruments in breast cancer patients.12

Stress

The Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R)13 was used to assess three symptom clusters associated with post-traumatic stress disorder: hyperarousal, intrusion, and avoidance. The IES-R asks respondents to rate their stress level based on the last 4 weeks regarding a traumatic event; survivors rated their stress related to their breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, and healthy control women rated their stress related to a stressful life event (e.g., serious personal illness, illness of a family member, loss of loved one, or loss of a job). A 5-point response scale is used ranging from 0=not at all to 4=extremely. Subscale sores are averaged and summated to create a total score. Higher scores indicate higher stress. High levels of internal consistency have been previously reported (0.96),14 and test-retest reliability across a 6-month interval ranged from .89 to .94.13

GENERAL PHYSICAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL, & ROLE FUNCTIONING

Sleep

Sleep quality over the past 4 weeks was measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).15 The scale yields seven “component” scores, including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Component scores are summed to create a global score. Global scores above 5 indicate poor sleep quality and scores of 8 or higher have been linked to daytime fatigue in BCS. The PSQI has solid psychometric properties including strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83) and overall consistency using test-retest over a 10-week period of time for the seven factors ranging from 0.68–0.79.15

Physical Function

Physical function was measured by the widely used RAND Physical Functioning scale (PF-10).16 The scale assesses the current extent that health limits physical activities, and higher scores reflect fewer limitations. The PF-10 is a commonly used instrument to measure physical functioning that has strong psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha 0.93)16 and has been used in BCS. 17

Social support

Social support was assessed with the Northouse Social Support Scale.18 The scale measures the current level of social support using a 5-point response scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree), with higher total scores reflecting more social support. The internal reliability of this scale has been reported as 0.90 in BCS, and construct validity has been confirmed by significant correlations with subscales on the Family Environment Scale.18

Spirituality. The spiritual perspective in an individual’s life was measured by the Reed Spiritual Perspective Scale.19 This is a 10-item instrument designed to measure the extent to which one currently holds certain spiritual views and engages in spiritually related interactions. Items are scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale, with total scores ranging from of 1=strongly disagree to 6=strongly agree and higher scores indicating greater spiritual perspective. The scale has demonstrated high internal (.93–.95) and satisfactory test-retest (.57–.68) reliability in several samples and has demonstrated associations with change in clinical status as well as spiritual views.19

AFFECTIVE STATES

Depression

Self-reported depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D).20 This scale measures symptoms that have occurred in the past week and uses a 4-point response scale (0=rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day] to 3=most or all of the time [5–7 days]). Higher scores indicate greater risk for depression. A score of 16 or above suggests clinical depression. The CES-D has shown strong correlation with other measures of depression and has good internal consistency.20

Positive change

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) was used to assess current perceived positive change after trauma.21 This scale has 5 subscales, including relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. A 6-point response scale ranges from 1=did not experience this change to 5=experienced this change to a very great degree. Subscale scores are summed to create a total scale score. Higher scores indicate more positive change. Scores from the instrument were shown to differentiate between breast cancer survivors and matched controls in several studies and to exhibit high levels of internal consistency (0.87)22

LIFE SATISFACTION

Life satisfaction

Present life satisfaction, a measure of overall or global well-being, was assessed with the Index of Well-being (IWB) scale.23 This scale measures current well-being, using an item response format with a 9-point semantic differential type scale. For example, to the stem “my present life is,” responses range from 1 = boring to 7 = interesting. Responses are summed for a total score. Higher scores reflect greater life satisfaction. The IWB was reported to have strong internal consistency in a previous study with BCS (n = 134, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92)8 and validity as it has been shown to correlate significantly with life quality and psychological adjustment.24

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics and distribution of all variables. African American survivors and controls were compared on health-related quality of life outcome measures using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusting for age, income, years of education, and body mass index. In these models, each health outcome was examined separately. The covariates were adjusted for based on the following rationale. Age and income have been shown in previous research to be important factors in assessing quality of life and, therefore, were viewed as important and potentially confounding covariates and were included in the model regardless of whether they significantly differed between the two groups.1 Other variables were included if their p value was less than a liberal alpha of .10 (see Table 2), including years of education and body mass index. A liberal alpha was chosen for the adjustment selection to ensure a conservative approach in subsequent ANCOVA models. Controlling for these confounding variables is important because it addresses concerns regarding equivalence between the two groups in this study and also addresses a limitation of previous studies, which have failed to address variables known to significantly impact quality of life.1, 25 The SAS software was used for all analyses.

Table 2.

Group Differences in Demographics

| AA Survivor N=62 |

AA comparison N=78 |

P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | STD | Mean | STD | ||

| Current Age | 57.3 | 8.4 | 52.2 | 15.4 | .015 |

| Number of years of education | 12.5 | 2.3 | 13.3 | 2.8 | .069 |

| Body Mass Index | 32.1 | 7.3 | 29.6 | 6.1 | .030 |

| Time Since Treatment (years) | 5.0 | 2.7 | -- | -- | -- |

| N | Percent | N | Percent | ||

| Marital Status | .550 | ||||

| Married or in a long-term relationship | 13 | 21.3 | 20 | 26.3 | |

| Other | 48 | 78.7 | 56 | 73.7 | |

| Highest Level of Education | .945 | ||||

| Greater than High School | 34 | 55.7 | 45 | 57.7 | |

| High School graduate/GED | 12 | 19.7 | 16 | 20.5 | |

| Less than High School | 15 | 24.6 | 17 | 21.8 | |

| Income | .212 | ||||

| <$15,000 | 31 | 50.8 | 34 | 43.6 | |

| $15,001 – $30,000 | 14 | 23.0 | 12 | 15.4 | |

| $30,001 – $75,000 | 7 | 11.5 | 19 | 24.4 | |

| >$75,000 | 2 | 3.3 | 6 | 7.7 | |

| Don’t know | 7 | 11.5 | 7 | 9.0 | |

P-value from Fisher’s exact test for categorical data, and two-sample t-test for continuous data.

Results

A total of 165 women were screened and determined eligible for study entry, with 140 (86%) consenting to participate. Of these, 62 were African American BCS and 78 were African American comparison women. These sample sizes provide 80% power for detecting a medium effect size of 0.48 standard deviation units between two group means.

The African American BCS were from 2 to 10 years post-diagnosis, with an average of 5 years (SD 2.7) post-treatment. The majority of survivors had Stage I to IIB breast cancer (85.7%), with the remaining diagnosed with Stage III (14.3%) disease. In addition, the majority of survivors had been treated with mastectomy (60.3%) and had both chemotherapy and radiation therapy (54.6%) as part of their treatment.

African American BCS were significantly older (M=57.3; SD=8.4) compared to the healthy comparison group (M=52.2; SD=15.4) and also on average had a higher body mass index (M=32.1 vs. 29.6) (See Table 2). The majority of African American BCS and comparison women were not married or in a long-term relationship. Most had a high school degree or higher, non-private health insurance (Medicare or Medicaid), and incomes of less than $30,000 (See Table 2).

Differences between African American BCS and African American Healthy Comparison Women

Health-related quality of life differences between groups are shown in Table 3. Reported means are “least squares” means, which are adjusted by the model for age, income, years of education, and body mass index. In the domain of disease-specific functioning, African American survivors experienced more fatigue (p=0.004) and worse hot flashes (p <0.001), but similar ratings of attention and event-related stress. In the domain of general physical, psychological, and role functioning, African American BCS reported worse sleep quality (p<0.001) but higher partner support (p=0.021) than comparison women. There were no group differences in physical functioning or spirituality. For affective states and life satisfaction, African American BCS reported more positive change (p=0.001) but similar depressive symptoms and overall well-being relative to comparison women. The 95% confidence interval is reported for the effect size for each comparison in Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences in Measures for African American BCS compared to Healthy Control

| African American Survivor n=62 |

African American Control n=78 |

P-valuea | Effect Size | 95%CI for Effect Size | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| N | LsMean | SD | N | LsMean | SD | ||||

| Disease-Specific Functioning | |||||||||

| Attention | 53 | 6.4 | 1.8 | 70 | 6.6 | 1.7 | .417 | −0.14 | (−0.49, 0.20) |

| Fatigue | 53 | 17.8 | 11.5 | 70 | 12.1 | 10.8 | .004 | 0.52 | (0.17, 0.87) |

| Hot flashes | 53 | 20.9 | 21.0 | 69 | 5.2 | 19.6 | .000 | 0.79 | (0.44, 1.13) |

| Stress | 53 | 13.8 | 16.1 | 69 | 16.1 | 15.1 | .399 | −0.15 | (−0.50, 0.20) |

| General Physical and Mental & Role Functioning | |||||||||

| Sleep | 52 | 9.0 | 4.2 | 70 | 6.1 | 4.0 | .000 | 0.71 | (0.36, 1.06) |

| Physical Functioning | 53 | 61.8 | 28.2 | 70 | 70.8 | 26.5 | .062 | −0.33 | (−0.68, 0.01) |

| Partner Social Support | 16 | 27.8 | 5.7 | 30 | 23.5 | 5.5 | .021 | 0.79 | (0.14, 1.43) |

| Spirituality | 53 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 70 | 5.2 | 0.8 | .294 | 0.19 | (−0.16, 0.53) |

| Affective States | |||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 53 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 70 | 11.6 | 11.0 | .757 | 0.05 | (−0.29, 0.40) |

| Positive change | 53 | 75.3 | 30.6 | 69 | 58.1 | 28.6 | .001 | 0.59 | (0.24, 0.94) |

| Life Satisfaction | |||||||||

| Life satisfaction | 52 | 11.7 | 3.2 | 70 | 11.9 | 3.0 | .709 | −0.07 | (−0.42, 0.28) |

p <.05

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval around effect size; LsMean, Least squares (i.e., adjusted) mean.

Discussion

This comparative study of African American BCS and African American women without a history of cancer comprehensively assessed health-related quality of life using Brenner and colleagues’ proximal-distal continuum. Based on previous research, it was hypothesized that African American BCS would have greater psychological and physical functioning concerns but similar generic and global well-being relative to African American women with no history of breast cancer. Findings suggest that, although there were commonalities on multiple health-related quality of life outcomes after controlling for demographic (age, education, and income) and clinical (body mass index) characteristics, important differences did emerge between these two groups. This study adds to the current literature in that it identifies health-related quality of life outcomes that are unique to African American BCS compared to a healthy comparison group of women, while controlling for potentially confounding variables that previous studies often failed to address.1 In addition, study findings support utilizing a framework that provides for a comprehensive assessment of quality of life.

Disease-Specific Functioning

The greatest number of group differences was noted in the proximal health-related quality of life outcomes. African American BCS reported more fatigue and worse hot flash bother but not more problems with attention and stress than African American healthy controls. Fatigue is the most common symptom reported by cancer survivors26 and has been identified as being a significant problem for African American breast cancer survivors compared to Asian, Latina, and white survivors.27 Fatigue is also one of the strongest predictors of overall quality of life in BCS. 28

African American BCS also reported more hot flash bother than controls, which is consistent with previous studies. In their multiethnic sample of 621 BCS, Giedzinska and colleagues29 found that hot flashes were one of the most troublesome physical symptoms for African Americans. Even after controlling for stage of diagnosis and treatment, Yoon 30 found that African American BCS reported more hot flashes than Caucasian and Hispanic BCS. Similar racial differences in hot flash frequency and bother have been reported in healthy women with no history of breast cancer after controlling for reproductive, medical, and life style variables. 31 Together, these findings indicate that African American women, and especially African American BCS, have relatively more problems with hot flashes. Future research is needed to explore contributing factors and underlying mechanisms of hot flash bother in these women.

We did not find that African American BCS had more problems with attention than the healthy comparison control group. Few studies have been done assessing subjective ratings of attention in BCS using the attention function index.32, 33 In a previous study of African American and Caucasian BCS, deficits in attention were linked to lower overall quality of life.33 More research is needed to understand the impact of cancer and its treatment on cognitive problems in BCS. Similarly, stress was not significantly different between the two groups after controlling for demographic and medical variables. This may have been due to the type or sensitivity of the stress instrument used in this study. However, these results are consistent with our previous comprehensive review, in which we noted few differences in stress between African American BCS and survivors of other ethnicities.1

General Physical, Psychological, and Role Functioning

Significant differences in the domain of general physical, psychological, and role functioning were noted between the two groups. African American BCS reported significantly worse sleep than comparison women. Poor sleep has been linked to poorer global quality of life in African American BCS.34 It is unclear what factors contribute to sleep problems in African American BCS, although menopausal symptoms (hot flashes) have been found to adversely affect sleep quality in BCS, 35 and research in non-cancer samples suggests that socioeconomic factors, coping styles, and menopausal symptoms may be linked to poor sleep and poor quality of life.36, 37

There were significant group differences in partner support, with BCS reporting higher levels of social support than the comparison group. In our previous comprehensive review, social support emerged as an important coping resource for African American BCS.1 Northhouse and colleagues found that receiving social support from family and friends provided African American survivors with meaningful ways to cope and reduced the stress associated with their breast cancer.18 Survivors with inadequate social support, on the other hand, have reported more quality of life concerns, such as decreased family well-being and negative mood states, than survivors with adequate support.34, 38 Contrary to studies comparing African American BCS with survivors of other ethnicities, there were no group differences in spirituality. Multiple studies have noted the importance of spirituality in coping for African American BCS1 and that African American BCS have high levels of spirituality.27 In addition, previous research has shown that spirituality is positively related to hope in African American survivors.39 Thus, it has been suggested that these survivors use this heightened spirituality to cope with the sequelae of breast cancer. These study findings suggest, however, that spirituality may be heightened in all African American women and not just triggered by breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Interestingly, while the BCS group reported more physical symptoms (fatigue, hot flashes, and sleep disturbance), no significant differences were noted in physical functioning between the two groups after controlling for demographic and medical variables. In a prior review, there were few noted differences in physical functioning between African American BCS and survivors of other ethnicities.1

Affective States

As for affective states, no differences in depressive symptoms between the groups were noted. This is consistent with our previous literature review, in which depressive symptoms were not as prominent for African American BCS compared to other survivors.1 This is also supported by a secondary study using data from the Women’s Health Initiative-Observational study, which found that African American BCS and African American women healthy-control women did not significantly differ in depression scores using the CES-D.25 Interestingly, African American BCS reported more positive growth. Past research indicates that African Americans report positive growth as a result of their breast cancer. This construct includes having a new meaning and increased appreciation for life,27 being positive about everyday living, avoiding dwelling on negative circumstances,40 and becoming a role model to provide inspiration and encouragement to others.40 Compared to Caucasian BCS, African American BCS have reported higher levels of positive meaning41 and both increased spirituality and better mental health.42

Although there were group differences in health-related quality of life outcomes along the continuum, there were no group differences in global quality of life or overall well-being. This finding is supported by our comprehensive literature review.1

The overall findings of this study indicate that, although breast cancer may produce negative effects (i.e., worse fatigue, hot flashes, and sleep disturbance), it may also produce positive changes (i.e., increased support and positive growth). These positive and negative changes may balance one another and may explain the non-significant differences in overall well-being between the two groups. In addition, these findings also support the importance of assessing health-related quality of life outcomes along a continuum. Brenner’s model indicates that assessing more distal outcomes using generic measures facilitates comparisons across groups and permits insight into global functioning.43 Disease-specific measures, on the other hand, can be used to identify and assess specific domains being affected by disease or treatment. And, as was noted in this study, specific measures also tend to be more sensitive and may register changes resulting from the disease that are not registered at more global levels.44

Limitations

Findings should be considered in terms of study limitations. First, the conceptual framework is a strength in that it allows for a comprehensive assessment of quality of life, but it needs further testing to identify and confirm appropriate measures for each domain. Second, the convenience sampling used in this study may have resulted in sampling bias and it raises concerns to as whether the sample was representative of the entire population. And finally, BCS who varied in time since treatment were included in this cross-sectional survey. Although our inclusion criteria are advantageous in increasing the generalizability of our findings, the criteria and study design do not provide information about how these outcomes may change over time.

Implications for Nursing Practice and Research

These findings suggest the importance of better understanding the context of the survivorship experience for racial and ethnic subgroups and of providing comprehensive assessments of health outcomes in the practice setting. By investigating Brenner and colleagues’ framework and determining the domains in which group differences occur, this study may provide a framework and suggested measures for clinicians and researchers to use in the future when assessing health-related quality of life in African American BCS. Study findings suggest areas in which breast cancer uniquely impacts African American BCS women relative to healthy African American women, and thus these findings point to potential clinical implications and future research priorities.

Findings from this study clearly demonstrate the need for clinicians to assess factors considered on the proximal end (disease-specific functioning) of the quality of life continuum for African American BCS. Based on these findings, if only global measures of quality of life (overall well-being) are used, clinicians may be limited in identifying factors that disproportionally and adversely affect African American BCS. Specifically, oncology nurses should prioritize the assessment of fatigue and hot flashes for African American BCS and incorporate this assessment as part of their routine clinical survivorship assessment. In addition, evidence-based nursing interventions are needed to manage fatigue, hot flashes, and sleep disturbances for African American BCS. Based on the findings of this study, these intervention programs should also capitalize on using existing resources such as social support and experiences of positive growth to enhance overall quality of life of African American BCS. Overall, by identifying the unique needs and resources of African American BCS, nurses will be better able to focus resources to those most in need.

Further research is needed to focus on the concerns identified in this study. Most importantly, nurse researchers should work to understand why African American BCS experience relatively more symptoms of fatigue, hot flashes, and sleep disturbance. One avenue would be to explore potentially common underlying mechanisms including genetic and environmental factors that may contribute to these symptoms in African American BCS.

Conclusions

This study is important because it adds to the current literature that identifies health-related quality of life outcomes unique to African American BCS versus healthy African American controls. As hypothesized, African American BCS reported favorable global health-related quality of life at the distal end of the continuum compared to the African American healthy control group. These survivors reported relatively more concerns with proximal measures of health-related quality of life, including greater fatigue, worse hot flashes, and worse sleep quality. This work supports previous assertions that a comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life factors is needed to fully understand the care needs of African American BCS. Although global indicators of quality of life are important, measurement of more proximal disease-specific functioning is essential for addressing the care needs of survivors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R03-CA97737 from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, Mary Margaret Walther Program, Walther Cancer Institute and grant #64194 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Nurse Faculty Scholar Award (PI: Von Ah). The authors would also like to thank Phyllis Dexter, PhD, RN for editing the paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Russell KM, Von Ah DM, Giesler RB, Storniolo AM, Haase JE. Quality of life of African American breast cancer survivors: how much do we know? Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(6):E36–45. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000339254.68324.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner MH, Curbow B, Legro MW. The Proximal-Distal Continuum of Multiple Health Outcome Measures: The Case of Cataract Surgery. Med Care. 1995;33(4):AS236–AS244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giesler RB. Assessing the quality of life of patients with cancer. Vol. 24. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(13):835–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware JE., Jr The status of health assessment 1994. Annu Rev Public Health. 1995;16:327–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.16.050195.001551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kooken W, Hasse JE, Russell K. I’ve been through something--a poetic exploration in cultural competence and caring of African American women breast cancer survivors. Western J Nurs Res. 2007;29(7):896–919. doi: 10.1177/0193945907302968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimprich B. Attentional fatigue following breast cancer surgery. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15(3):199–207. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Ah D, Russell KM, Storniolo AM, Carpenter JS. Cognitive dysfunction and its relationship to quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(3):326–336. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.326-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cimprich B, Visovatti M, Ronis DL. The Attentional Function Index--a self-report cognitive measure. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):194–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D. Factors influencing quality of life in cancer patients: Anemia and fatigue. Semin Oncol. 1998;25(Suppl 3):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter JS. The Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale: a tool for assessing the impact of hot flashes on quality of life following breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(6):979–989. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss D. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In: Wilson J, Tang C, editors. Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD. Springer US; 2007. pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale - Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallinson T, Cella D, Cashy J, Holzner B. Giving meaning to measure: Linking self-reported fatigue and function to performance of everyday activities. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(3):229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Northouse LL. Social support in patients’ and husbands’ adjustment to breast cancer. Nurs Res. 1988;37(2):91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed PG. Spirituality and well-being in terminally ill hospitalized adults. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10(5):335–344. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):487–497. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell A, Converse PE, Rodgers WL. The quality of American life: Perceptions, evolutions, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longman AJ, Braden CJ, Mishel MH. Side-effects burden, pychological adjustment and life quality in women with breast cancer: Patterns of associateion over time. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:909–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paskett ED, Alfano CM, Davidson MA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ health-related quality of life : racial differences and comparisons with noncancer controls. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3222–3230. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell SA. Cancer-related fatigue: state of the science. PM R. 2010;2(5):364–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Tejero JS, Kim J. Breast cancer survivorship in a multiethnic sample: challenges in recruitment and measurement. Cancer. 2004;101(3):450–465. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. A population-based study of the impact of specific symptoms on quality of life in women with breast cancer 1 year after diagnosis. Cancer. 2006;107(10):2496–2503. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, Rowland JH. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28(1):39–51. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon J, Malin JL, Tao ML, et al. Symptoms after breast cancer treatment: are they influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108(2):153–165. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cimprich B, So H, Ronis DL, Trask C. Pre-treatment factors related to cognitive functioning in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14(1):70–78. doi: 10.1002/pon.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Ah D, Russell KM, Storniolo AM, Carpenter JS. Cognitive Dysfunction and Its Relationship to Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(3):326–336. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.326-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Northouse LL, Caffey M, Deichelbohrer L, et al. The quality of life of African American women with breast cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22:449–460. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(199912)22:6<449::aid-nur3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter JS, Elam JL, Ridner SH, Carney PH, Cherry GJ, Cucullu HL. Sleep, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors and matched healthy women experiencing hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(3):591–5598. doi: 10.1188/04.onf.591-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kripke DF, Jean-Louis G, Elliott JA, et al. Ethnicity, sleep, mood, and illumination in postmenopausal women. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall M, Bromberger J, Matthews K. Socioeconomic status as a correlate of sleep in African-American and Caucasian women. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:427–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman LC, Kalidas M, Elledge R, et al. Optimism, social support and psychosocial functioning among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):595–603. doi: 10.1002/pon.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson LM, Parker V. Inner resources as predictors of psychological well-being in middle-income african american breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2003;10(5 Suppl):52–59. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez ED, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(1):99–115. doi: 10.1177/1049732304270766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bower JE, Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA, Bernaards CA, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. Perceptions of positive meaning and vulnerability following breast cancer: predictors and outcomes among long-term breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(3):236–245. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2903_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowen DJ, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, et al. Possible socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(1):85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD, Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short- form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guyatt GH, Eagle DJ, Sackett B, et al. Measuring quality of life in the frail elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1433–1444. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90143-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]