Abstract

Rationale: Gene expression profiling of airway epithelial and inflammatory cells can be used to identify genes involved in environmental asthma.

Methods: Airway epithelia and inflammatory cells were obtained via bronchial brush and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from 39 subjects comprising three phenotypic groups (nonatopic nonasthmatic, atopic nonasthmatic, and atopic asthmatic) 4 hours after instillation of LPS, house dust mite antigen, and saline in three distinct subsegmental bronchi. RNA transcript levels were assessed using whole genome microarrays.

Measurements and Main Results: Baseline (saline exposure) differences in gene expression were related to airflow obstruction in epithelial cells (C3, ALOX5AP, CCL18, and others), and to serum IgE (innate immune genes and focal adhesion pathway) and allergic–asthmatic phenotype (complement genes, histone deacetylases, and GATA1 transcription factor) in inflammatory cells. LPS stimulation resulted in pronounced transcriptional response across all subjects in both airway epithelia and BAL cells, with strong association to nuclear factor-κB and IFN-inducible genes as well as signatures of other transcription factors (NRF2, C/EBP, and E2F1) and histone proteins. No distinct transcriptional profile to LPS was observed in the asthma and atopy phenotype. Finally, although no consistent expression changes were observed across all subjects in response to house dust mite antigen stimulation, we observed subtle differences in gene expression (e.g., GATA1 and GATA2) in BAL cells related to the asthma and atopy phenotype.

Conclusions: Our results indicate that among individuals with allergic asthma, transcriptional changes in airway epithelia and inflammatory cells are influenced by phenotype as well as environmental exposures.

Keywords: environmental asthma; microarray; house dust mite; lipopolysaccharide; atopy

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

To identify genes involved in regulating environmental asthma, we performed gene expression profiling on airway epithelial and inflammatory cells obtained by bronchoscopy from 39 patients with asthma after exposure to LPS or house dust mite antigen.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We found that among subjects with allergic asthma, transcriptional changes in airway epithelia and inflammatory cells are influenced by phenotype but are also substantially affected by environmental exposures, such as LPS and to a much smaller extent house dust mite allergen.

Asthma is a chronic airway disorder that is characterized by variable reversible airflow obstruction and airway hyperresponsiveness. Although host factors that make one susceptible to asthma are complex and poorly understood, it is clear that a genetic component to asthma susceptibility exists (1–3). Although genes and genetic loci that have been implicated in asthma are numerous, validation in independent cohorts and populations has been largely unsuccessful (1). This is likely due to complex gene–gene interactions, environmental exposures, varying phenotypic definitions, and genetic admixture of study populations.

The environment plays an important role in the development and progression of asthma. Environmental agents with direct and indirect effects on asthma include aeroallergens, tobacco exposure, agents in the workplace, indoor and outdoor air pollution, viruses, and domestic and occupational exposure to endotoxin (4). Given the unique aspects of these agents, it is likely that distinct biological pathways are stimulated when the airway is challenged with each of these agents. This leads us to speculate that genes with altered expression in the airways of individuals with asthma after specific subsegmental airway challenges may provide a way of identifying asthma susceptibility genes.

Whole-genome transcriptional analysis is well suited for identifying genes involved in the pathogenesis of asthma, as well as other complex diseases. Lilly and colleagues described a number of genes differentially expressed in the airway epithelia of individuals with allergic asthma after environmental challenge with allergens, indicating that multiple genes and gene pathways are involved in such a response (5). Woodruff and colleagues used gene expression profiles of airway epithelia from subjects with mild-to-moderate asthma and healthy control subjects to classify subjects with asthma on the basis of high or low expression of IL-13–inducible genes (6). Finally, gene expression signatures of mild and severe asthma in induced sputum (7) and peripheral blood have been also described (8, 9).

In this investigation, we have analyzed the transcriptional response in airway epithelia and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells obtained from human subjects with or without allergies and/or asthma after airway instillation of saline, LPS, or house dust mite antigen (HDM). Our findings identify genes associated with airflow obstruction and indicate that classes of immune genes differentiate normal subjects from individuals with allergic asthma. Moreover, LPS induces a clear biological response in airway epithelia and inflammatory cells irrespective of allergic or asthmatic phenotype, whereas HDM induces a subtle transcriptional response in subjects with asthma or atopy in airway inflammatory cells but not epithelia.

Methods

Subject Recruitment and Sample Acquisition

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC). Volunteers between 18 and 40 years of age underwent a comprehensive screening protocol to define asthma and atopy phenotypes. Subjects with asthma were identified on the basis of a physician diagnosis of asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness, defined as a 20% decrease in FEV1 after inhalation of methacholine at less than 8 mg/ml. Atopy was defined as having seasonal symptoms requiring medications and a positive skin-prick reaction to house dust mite and at least three other aeroallergens (wheal : 3 mm). Normal subjects must have had no diagnosis of asthma or allergic rhinitis, negative methacholine challenge, and negative allergen skin tests.

Airway Challenge Protocol

Each subject had two bronchoscopies performed, separated by 4 hours. During the first bronchoscopy, 39 subjects had all three subsegmental airways instilled with saline, LPS, and HDM. Four hours later, BAL was performed on three subsegmental airways in all subjects. Thirty-seven subjects had subsegmental bronchi that were successfully sampled for airway epithelia (via endobronchial brushing) 4 hours after instillation of saline, LPS and HDM. The following numbers of RNA samples and arrays passed quality control and were included in the analyses: (1) epithelial cells: 37 saline, 37 LPS, and 34 HDM; and (2) inflammatory cells: 29 saline, 33 LPS, and 31 HDM.

Microarray Data Analysis

A total of 21,316 and 30,696 probes passed the signal-intensity filter, respectively, in airway epithelial and inflammatory data sets. Details related to quality-control screening, data normalization, and statistical analysis of the microarray data are provided in the online supplement. The microarray hybridizations were performed in two batches separated by approximately 1 year. To control for differences between batches, we included a batch term in all statistical models, following the approach described in Reference 10. Principal components analysis figures in Table E1 (see the online supplement) demonstrate successful removal of batch effects. We also included sex as a covariate in all statistical models. Models including age and race showed that these factors did not contribute significantly to variance in gene expression and were therefore not included in the final analyses. Expression associations were identified by analysis of variance/covariance models with repeated measures in some cases. These analyses were performed in Partek (St. Louis, MO). Overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) categories, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways, and TRANSFAC transcription factor–binding sites (TFBSs) were identified using the GATHER utility (11). The microarray data have been deposited in the publicly accessible Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession numbers GSE8190 (airway epithelia) and GSE5272 (inflammatory cells).

Results

Study Subject Demographics

Demographics for subjects enrolled in the study are presented in Table 1. As expected, subjects with atopy (with or without asthma) had more positive skin-prick test reactions (P < 0.0001) and higher serum IgE levels (P < 0.001). Distributions of age, sex, and race were similar among the study groups.

TABLE 1.

SUBJECT DEMOGRAPHICS AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

| Atopy/Asthma Status |

|||

| −/− (Control) | +/− (Atopy Only) | +/+ (Atopy/Asthma) | |

| Number | 13 | 12 | 14 |

| Sex: male/female | 8/5 | 7/5 | 6/8 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 24 ± 6 | 26 ± 10 | 26 ± 8 |

| Race: Caucasian/African American | 10/3 | 8/4 | 9/5 |

| Height, in | 69 ± 4 | 68 ± 3 | 68 ± 4 |

| Weight, kg | 78 ± 25 | 75 ± 14 | 77 ± 18 |

| log IgE, IU/ml | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 83 ± 8 | 84 ± 5 | 78 ± 5 |

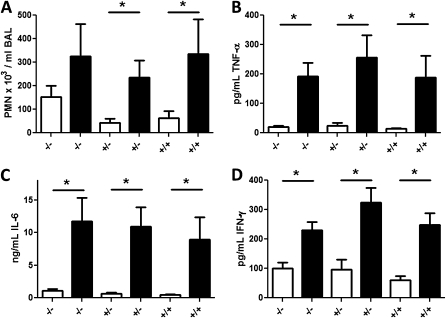

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Inflammatory Cell and Cytokine Analysis

The BAL neutrophil count was increased in LPS-instilled segments compared with saline control in all three phenotypes (Figure 1A). The concentrations of helper T-cell type 1 (Th1) cytokines IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IFN-γ in the BAL fluid were significantly increased in LPS-instilled segments versus saline-instilled segments (Figures 1B–1D). No significant differences in neutrophil infiltration or cytokine concentrations were observed between phenotypes in the LPS-challenged airways. No significant changes in BAL neutrophil count or Th1 cytokines were observed for the HDM-instilled airways (data not shown). We also examined eosinophil infiltration and Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 after HDM challenge and, surprisingly, observed no consistent differences compared with saline-challenged airways. Collectively, these data demonstrate that instillation of LPS, but not HDM, induces a robust airway inflammatory response that is not modulated by the asthma or atopy phenotype.

Figure 1.

Inflammatory response in the lung is increased in response to LPS instillation. (A) LPS instillation induced significant increases in neutrophils (PMNs) in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of all study subjects. Concentrations of (B) tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, (C) IL-6, and (D) IFN-γ were increased in response to LPS in the three study groups: −/− (nonatopic nonasthmatic), –/+ (nonatopic asthmatic), and +/+ (atopic asthmatic). Open columns represent saline and solid columns represent LPS treatment. *P < 0.05 by two-tailed Student t test.

Gene Expression Profiles

We focus on several aspects of the gene expression data: (1) genes associated with asthma and atopy, including clinically diagnosed or measured phenotypes identified in samples exposed to the saline control; (2) exposure associations regardless of phenotype; and (3) exposure–phenotype interaction associations. All analyses are summarized in Table 2. Table 2 includes information on the model that was used in the analysis and numbers of significant genes along with thresholds used to define significance. Analyses that yielded no significant findings (HDM exposure for both epithelial cells and BAL cells, and exposure–phenotype interaction in epithelial cells) are not discussed further in this article.

TABLE 2.

SUMMARY OF GENE EXPRESSION ANALYSES

| Model | Factor of Interest* | Data Used (Exposure; Phenotype) | Cell Type | P Value Cutoff | FDR Cutoff (%) | Significant Genes | Supplementary Table No. |

| RM-ANOVA | Asthma/atopy vs. nonasthma/nonatopy | All exposures; +/+ and −/− groups | Epithelial | 0.05 | 5 | 259 | E1 |

| ANCOVA | FEV1/FVC | Saline; all three groups | Epithelial | 0.001 | 20 | 114 | E2 |

| ANCOVA | FEV1/FVC | Saline; +/+ group | Epithelial | 0.05 | 20 | 0 | NA |

| ANCOVA | IgE | Saline; all three groups | Epithelial | 0.05 | 5 | 42 | E3 |

| RM-ANOVA | Asthma/atopy vs. nonasthma/nonatopy | All exposures; +/+ and −/− phenotypic groups | BAL | 0.01 | 5 | 1,767 | E4 |

| ANCOVA | FEV1/FVC | Saline; all three groups | BAL | 0.001 | 20 | 58 | E5 |

| ANCOVA | FEV1/FVC | Saline; +/+ group | BAL | 0.05 | 20 | 0 | NA |

| ANCOVA | IgE | Saline; all three groups | BAL | 0.05 | 5 | 432 | E6 |

| ANOVA | LPS exposure | LPS and saline; all three groups | Epithelial | 0.001 | 5 | 388 | E7 |

| ANOVA | HDM exposure | HDM and saline; all three groups | Epithelial | 0.05 | 20 | 0 | NA |

| ANOVA | LPS exposure | LPS and saline; all three groups | BAL | 0.001 | 5 | 5,518 | E8 (only >2-fold) |

| ANOVA | HDM exposure | HDM and saline; all three groups | BAL | 0.05 | 20 | 0 | NA |

| RM-ANOVA | LPS × asthma and HDM × asthma interactions | All exposures; all three groups | Epithelial | 0.05 | 20 | 0 | NA |

| RM-ANOVA | LPS × atopy and HDM × atopy interactions | All exposures; all three groups | Epithelial | 0.05 | 20 | 0 | NA |

| RM-ANOVA | LPS × asthma and HDM × asthma (compared with saline × nonatopy) | All exposures; all three groups | BAL | 0.05 | 5 | 1,529 (LPS); 251 (HDM) | E9 (LPS); E10 (HDM) |

| RM-ANOVA | LPS × atopy and HDM × atopy (compared with saline × nonatopy) | All exposures; all three groups | BAL | 0.05 | 5 | 1,868 (LPS); 52 (HDM) | E11 (LPS); E12 (HDM) |

Definition of abbreviations: ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; ANOVA = analysis of variance; BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage; FDR = false discovery rate; HDM = house dust mite allergen; NA = not applicable; RM-ANOVA, repeated measures-analysis of variance.

All models included batch and sex as cofactors.

Gene Expression Changes Associated with Asthma and Atopy

Gene expression changes associated with asthma and atopy in epithelial cells.

Transcriptional changes in subjects with atopic asthma compared with those without atopic asthma are generally small in magnitude (17 of 259 genes with >1.5-fold change) but include genes previously associated with asthma (ADAMTSL1), innate immunity (GSK3, DEFB114, MAPK13), complement components (CFB, C4B), and transcription factors (GATA2, SP2). The top up-regulated gene is fibromodulin, a proteoglycan involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition.

Gene expression changes after saline instillation associated with airflow obstruction and serum IgE in epithelial cells.

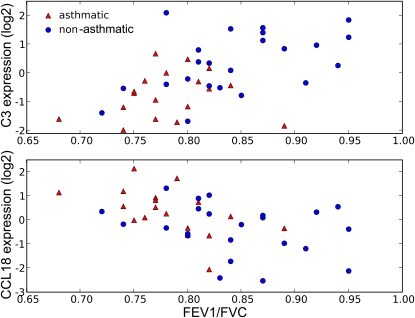

Among all study subjects, we considered whether gene expression changes were associated with measures of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC ratio) and serum IgE concentrations. Among 114 genes associated with FEV1/FVC are C3 and CCL18. Figure 2 shows increased baseline expression of CCL18 and decreased expression of C3 in subjects with higher degrees of airflow obstruction. To identify genes expressed by airway epithelia more specific to asthma, we ranked the airflow obstruction genes by the strength of association and found that the top genes are as follows: C3 (P = 0.00004, twofold decreased expression in subjects with asthma vs. those without asthma), lactotransferrin (LTF) (P = 0.003, 70% decreased), and CCL18 (P = 0.003, 60% increased). When we performed these analyses in subjects with asthma alone, we did not identify any significant gene expression changes. This is likely due to the small sample size and we therefore were not able to identify relative contributions of disease status and lung function in these individuals. Alternatively, these gene expression changes may differentiate asthma from nonasthma rather than affect lung function specifically. Interestingly, one of the most negatively correlated genes (partial correlation coefficient, –0.34) with serum IgE levels is IRAK4, a kinase that activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB in both the Toll-like receptor (TLR) and T cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathways.

Figure 2.

Illustration of association between airflow obstruction and baseline expression of two genes selected from Table E1: (top) C3 and (bottom) CCL18. The expression values are as observed in airway epithelia after exposure to the saline control (relative to the mean overall subjects).

Gene expression changes associated with asthma and atopy in inflammatory cells.

Expression changes in subjects with atopic asthma compared with individuals without atopic asthma were found for several genes relevant to the immune response (CXCL9, CIITA, HMGB1, IL17RB, NALP1, HLA-DQA2), complement (C2, CR1), and histone deacetylases (HDAC4, HDAC10). Other differentially expressed genes associated with allergic asthma were involved in housekeeping processes such as protein synthesis (data not shown). The top overrepresented TFBSs in the gene list include NF-Y and GATA1.

Gene expression changes after saline instillation associated with airflow obstruction and serum IgE in inflammatory cells.

Fewer genes were associated with airway obstruction in the inflammatory cells compared with the epithelial cells. The MHC class II gene HLA-DQB2 was the only identified biologically relevant gene found to be associated with baseline FEV1/FVC in inflammatory cells. As for the epithelial cells, our sample size was too small to identify significant changes only in subjects with asthma. Finally, many more genes were associated with serum IgE concentrations in airway inflammatory cells compared with epithelial cells. Two genes whose expression was positively associated with serum IgE in inflammatory cells, chitinase domain containing 1 (CHID1) and IFN, α-inducible protein 27 (IFI27) have potential relevance to asthma (12). Pathway analysis of the transcript data set found the focal adhesion KEGG pathway also to be associated with serum IgE (P = 0.008) in inflammatory cells.

Transcriptional Response to LPS

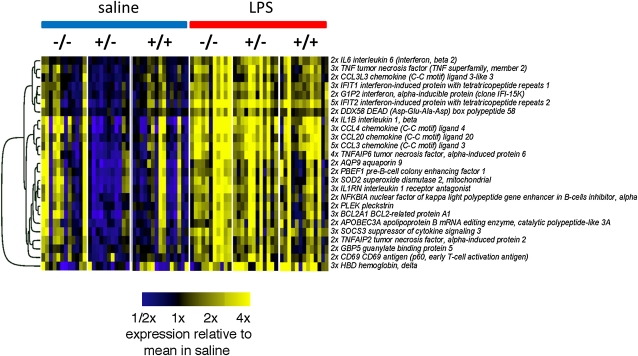

Gene expression response to LPS in airway epithelia.

The gene expression data reveal a clear response to LPS for subjects in all phenotypic groups in samples of airway epithelia. Almost all 388 significant transcripts had heightened expression after LPS exposure, with only 20 showing attenuated expression as a result of LPS treatment (Figure 3 for transcripts with a greater than twofold change). According to an analysis of GO terms, airway epithelial gene transcription after LPS exposure is characteristic of an inflammatory immune response, including elevated expression of various cytokines and chemokines. TFBS analysis identified several transcription factors known to regulate the innate immune response, including IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE), NF-κB, NRF2, Ikaros, IRF7, and E2F1.

Figure 3.

A heatmap of the LPS-responsive genes in airway epithelia with a greater than twofold change in expression versus saline. The genes are clustered by similarity in expression as quantified by the Pearson correlation using average linkage hierarchical clustering. The three study groups are as follows: −/− (nonatopic nonasthmatic), +/− (atopic nonasthmatic), and +/+ (atopic asthmatic).

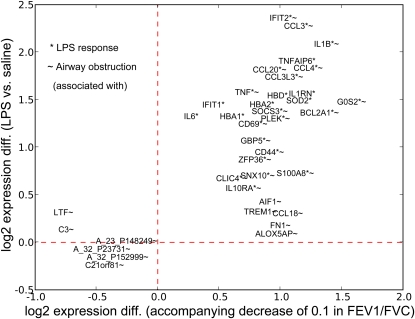

Although no clear relationship exists between LPS-induced changes in airway epithelia gene expression and asthma, our analysis identified several LPS-induced genes that were associated with the FEV1/FVC ratio. The top 20 LPS response and the top 20 airflow obstruction genes were plotted to indicate both the strength of association with FEV1/FVC and fold change induced by LPS (Figure 4). The figure identifies genes more specific to airflow obstruction (e.g., C3, CCL18, LTF, TREM1, ALOX5AP, and FN1), to the LPS response (IL6, IFIT1, HBD, and TNFAIP6), and those showing a strong relation to both factors (IFIT2, IL1B, and CCL3) in airway epithelia.

Figure 4.

The top 20 LPS-responsive genes and the top 20 genes associated with airflow obstruction in airway epithelia. The plot indicates the approximate degree of association of the various genes with each factor. For example, C3, LTF, ALOX5AP, and FN1 appear specific to airflow obstruction; IL6 and IFIT1 are more specific to the LPS response; and many (IFIT2, CCL3, IL1B) show a relation to both.

Gene expression response to LPS in inflammatory cells.

As expected, the most dramatic response in the airway inflammatory cell expression data was that associated with the exposure to LPS. We identified 5,518 differentially expressed transcripts between LPS- and saline-exposed samples, with 268 transcripts having a greater than 2-fold difference in expression. According to GO annotations, LPS-induced genes with increased expression relative to saline are involved in inflammation, the immune response, chemotaxis, apoptosis, and chromosome organization. Genes with decreased expression are largely involved in ATP synthesis; these include mitochondrial genes (GO) and genes in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (KEGG). Similar to the epithelial cell gene expression data, TFBS analysis identified transcription factors known to regulate innate immunity, specifically IFN consensus sequence–binding protein (ICSBP), ISRE, IRF, NF-κB, NRF2, C/EBP, and E2F1.

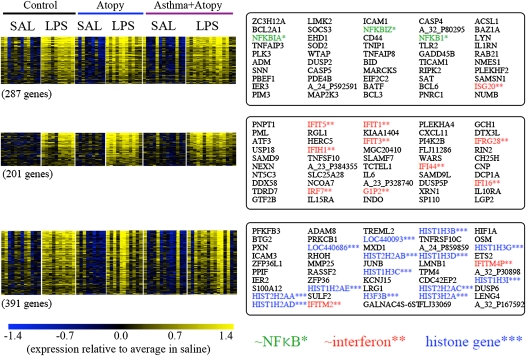

To identify groups of possible concordantly expressed genes that may be associated with more specific processes initiated after instillation of LPS, we performed k-means clustering (k = 30) on the expression data for the 5,518 LPS-response genes we identified. The three clusters of genes with highest average change in expression induced by LPS are shown in Figure 5; the first is enriched with genes associated with activation of NF-κB, the second with IFN-inducible genes, and the third with histone genes.

Figure 5.

Clusters of LPS-responsive genes in inflammatory cells. The top three clusters—those with genes having highest average fold change in response to LPS—were identified by k-means clustering of LPS-responsive genes. This analysis identifies what appear to be three key components of the LPS response. The top 50 genes within each cluster are shown (note that the genes here are ranked by the similarity of expression, i.e., correlation, with the average for all genes in the cluster). SAL = saline.

Interaction Analysis of Phenotype and Exposure in Inflammatory Cells

Our final set of analyses contrasted exposure-specific (LPS or HDM; compared with saline) transcriptional profiles in two phenotypes (asthma compared with nonasthma, or atopy compared with nonatopy). This analysis revealed significant changes in subjects with asthma versus subjects without asthma in response to LPS as well as moderate changes in response to HDM in inflammatory cells. Genes with significant differential expression in response to LPS in subjects with asthma compared with subjects without asthma include those associated with immune defense and stress response GO categories; apoptosis, cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, and TLR signaling KEGG pathways; as well as binding sites for NF-κB, ELK-1, ICSBP, ISRE, E2F1, and IRF7 transcription factors. The majority of the genes are induced or repressed by less than twofold in response to LPS compared with saline in subjects with asthma compared with subjects without asthma. The exception to this are many cytokines and chemokines, IFN-inducible genes, and NF-κB subunits, all of which are induced between 2- and 11-fold. Adrenomedullin was one of the top differentially expressed genes in response to LPS in subjects with asthma as compared with subjects without asthma (3.1-fold up-regulation). On the other hand, protein biosynthesis and metabolism GO categories, purine and amino acid KEGG pathways, as well as binding sites for GATA1 and GATA2 transcription factors are differentially expressed in response to HDM in subjects with asthma compared with subjects without asthma. Almost all genes are differentially expressed by 20–40% (1.2- to 1.4-fold up- or down-regulation), suggesting that transcriptional response to HDM in subjects with asthma compared with subjects without asthma is minimal, not only in the number of genes but also in the magnitude of changes.

In comparing subjects with atopy with subjects without atopy, there were significant transcriptional changes in response to LPS as opposed to minimal changes in response to HDM. Genes that are differentially expressed in response to LPS in subjects with atopy compared with subjects without atopy overlap significantly with genes that are induced by LPS in subjects with asthma compared with subjects without asthma (∼1,000 genes in common to the two analyses), suggesting that the transcriptional response to LPS is robust and not strongly influenced by phenotype. As expected, on the basis of the overlap of the two gene lists, the same GO categories, KEGG pathways, TFBSs, and top up-regulated genes are present in response to LPS in subjects with atopy compared with subjects without atopy and in individuals with asthma compared with individuals without asthma. Finally, genes that are significantly differentially expressed in response to HDM in individuals with atopy compared with individuals without atopy are associated with similar GO categories and KEGG pathways as those in individuals with asthma compared with individuals without asthma but included different TFBS (E2F1:DP1, HIF1α, and c-ETS1).

Discussion

Our results indicate that among individuals with allergic asthma, transcriptional changes in airway epithelia and inflammatory cells are influenced by phenotype as well as environmental exposures. For instance, we demonstrated that HDM induces a subtle but perceptible transcriptional response in subjects with asthma or atopy in inflammatory cells (adrenomedullin, GATA1, and GATA2) but not in airway epithelia. Our results demonstrate a strong and clear biological response to LPS in airway epithelia and inflammatory cells irrespective of phenotype, with some variation in gene expression noted with asthma and atopy. Furthermore, phenotype and exposure are interactive, and demonstrate expression changes in the inflammatory cells of subjects with asthma versus those without asthma in response to LPS, as well as HDM.

Transcriptional differences in allergic–asthmatic versus nonallergic–nonasthmatic groups are enriched for NF-Y, a transcription factor that regulates MHCII gene expression (13) and GATA1, a member of the family of transcription factors involved in Th2 cell differentiation (14). Overexpression of fibromodulin and other ECM genes is consistent with enhanced ECM deposition in asthmatic airways (15).

Among genes associated with airflow obstruction, the elevated expression of 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (ALOX5AP) observed in subjects with more extensive obstruction is consistent with the bronchoconstrictive properties of leukotrienes. Genetic association studies of polymorphisms in ALOX5AP and ALOX5 (16, 17) also suggest an influence more specifically on lung function rather than asthma. The association of complement component 3 (C3) expression with airflow obstruction and asthma is consistent with results from several mouse and human studies. C3-deficient mice show diminished airway hyperresponsiveness after allergen challenge (18), and C3 single-nucleotide polymorphism genotype associations with asthma have been identified in Japanese and African-Caribbean populations (19, 20). The observed decreased expression of C3 in individuals with asthma (vs. individuals without asthma) might seem to contradict what would be expected for a condition associated with heightened inflammation. However, there is no reason to expect a simple relationship between gene expression in one specific cell type and the levels and activities of the associated proteins and of the states of neighboring cells. The data of Spira and colleagues (21) also show decreased expression of C3 in airway epithelia in response to an exposure, cigarette smoking, also associated with increased inflammation.

In addition to genes previously associated with airway obstruction in individuals with asthma, our study also identified novel candidates. For example, CCL18, which shows the strongest association with airflow obstruction in epithelial cells, has been previously associated with various inflammatory diseases (22), but its involvement in asthma has been explored only more recently (23). Similarly, HLA-DQB2, an MHC class II gene, has previously been associated with asthma but not specifically with airflow obstruction. In addition to immune-related genes associated with serum IgE, we also observed enrichment in the focal adhesion pathway, a finding that has not been previously reported.

Although gene expression changes are observed in association with clinical phenotypes of asthma, both airway epithelial and inflammatory cell gene transcription appears to be much more strongly influenced by exposure to LPS. Epithelial cells show a greater than twofold up-regulation of key inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and broadly reveal a pattern of expression consistent with NF-κB activation and IFN regulation. These data also identify a number of less well-characterized genes such as IFIT2, which had the greatest fold induction (∼fivefold) by LPS. TFBS analysis revealed an association with transcription factors with established roles in cellular response to LPS, namely NF-κB and IFN signaling. IRF7, found both by expression and TFBS analysis, has been described as the “master” regulator of the type I IFN–dependent immune response (24). The ISRE motif was also identified by analysis of genes associated with neutrophil recruitment to the lung in mice after LPS inhalation (25).

The transcriptional response of inflammatory cells to instilled LPS was robust and consistent across study groups. After LPS, there was significant (>fourfold) differential expression of genes involved in cell–cell signaling and innate and adaptive immune mechanisms, and also a number of chemokines thought to be involved in T-cell chemoattraction (CXCL11, CCL20, CD69), endothelial cell activity (EDN1), oxygen metabolism (SOD2), and cell cycle initiation (G0S2). In addition to genes involved in inflammation and innate immunity and various mechanisms of cell injury and repair, there are a host of other genes that have only more recently been recognized as being involved in asthma pathogenesis, such as genes involved in histone activity (26) and with metalloproteinase activity (27). One particularly interesting candidate gene in asthma pathogenesis is adrenomedullin, which was up-regulated after exposure to LPS. One study found that plasma adrenomedullin levels correlate with the severity of human asthma (28) whereas another found that plasma levels of adrenomedullin were increased during acute attacks of asthma (29). Overall, it is thought that adrenomedullin may have important bronchodilating effects in human airways.

Our analysis of interactions between phenotype (asthma or atopy) and exposure (LPS or HDM) has identified specific genes that are modulated by asthma or atopy. The LPS response consisted of largely the same genes, albeit with variable expression, underscoring the robustness of the response of both airway epithelia and inflammatory cells to LPS. Although analysis of the response to HDM in all subjects did not reveal any consistent changes across all phenotypic groups, the interaction analysis identified genes that are differentially expressed specifically in subjects with asthma compared with subjects without asthma or in individuals with atopy compared with those without atopy. Both GATA1 and GATA2 transcription factors (14) were involved in the transcriptional response to HDM.

There are several potential reasons that the response to HDM was subtle. First, inconsistent response to HDM may be a result of different degrees of sensitization to HDM, which may have limited transcriptional response to this allergen. Second, the HDM response may have been more pronounced at a time point distinct from when the second bronchoscopy was performed. Third, it is possible that our instilled dose of HDM may have been insufficient to stimulate an allergic response in the airway. Modest doses of HDM were employed to ensure patient safety and we did not observe an eosinophilic or Th2 response to instilled HDM. Finally, some of our analyses may suffer from small sample sizes.

In conclusion, we have identified specific gene expression signatures in response to LPS and to a lesser extent HDM in human airway epithelial and inflammatory cells. There is variable expression of these genes dependent on the asthmatic and atopic phenotype. These findings suggest that gene expression profiling can help identify those cell signaling pathways that are specific to environmental exposures and objective signs of allergic airway disease. These gene expression profiles may be useful in the future in tailoring therapy based on specific environmental exposures and susceptibility genes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES18181, ES011185, ES012496, and intramural funds); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL082055 and intramural funds); and the National Center for Research Resources, Clinical Research Centers Program (M01-RR-30).

Author Contributions: I.V.Y., J.T., and J.S. analyzed the data; I.V.Y., D.A.S., J.T., and J.S. wrote the manuscript; J.S.S. and D.A.S. designed the study; J.S., C.M.S., H.E.M., L.G.Q., J.S.S., and D.A.S. collected the samples; S.F. and E.M.-T. performed laboratory work.

This article has an online supplement, which is available from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1503OC on January 12, 2012

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Vercelli D. Discovering susceptibility genes for asthma and allergy. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:169–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wills-Karp M, Ewart SL. Time to draw breath: asthma-susceptibility genes are identified. Nat Rev Genet 2004;5:376–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cookson WO, Moffatt MF. Genetics of complex airway disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2011;8:149–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz DA. Does inhalation of endotoxin cause asthma? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:305–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lilly CM, Tateno H, Oguma T, Israel E, Sonna LA. Effects of allergen challenge on airway epithelial cell gene expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:579–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2–driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:388–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hastie AT, Moore WC, Meyers DA, Vestal PL, Li H, Peters SP, Bleecker ER. Analyses of asthma severity phenotypes and inflammatory proteins in subjects stratified by sputum granulocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:1028–1036e1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahmoun M, Foussat A, Groux H, Pene J, Yssel H, Chanez P. Enhanced frequency of CD18- and CD49b-expressing T cells in peripheral blood of asthmatic patients correlates with disease severity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2006;140:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansel NN, Hilmer SC, Georas SN, Cope LM, Guo J, Irizarry RA, Diette GB. Oligonucleotide-microarray analysis of peripheral-blood lymphocytes in severe asthma. J Lab Clin Med 2005;145:263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Achiron A, Gurevich M, Friedman N, Kaminski N, Mandel M. Blood transcriptional signatures of multiple sclerosis: unique gene expression of disease activity. Ann Neurol 2004;55:410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JT, Nevins JR. GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomic signatures. Bioinformatics 2006;22:2926–2933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CG, Da Silva CA, Dela Cruz CS, Ahangari F, Ma B, Kang MJ, He CH, Takyar S, Elias JA. Role of chitin and chitinase/chitinase-like proteins in inflammation, tissue remodeling, and injury. Annu Rev Physiol 2011;73:479–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boss JM. Regulation of transcription of MHC class II genes. Curr Opin Immunol 1997;9:107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finotto S. T-cell regulation in asthmatic diseases. Chem Immunol Allergy 2008;94:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, Olivenstein R, Taha R, Hamid Q, Ludwig M. Enhanced proteoglycan deposition in the airway wall of atopic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:725–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kedda MA, Worsley P, Shi J, Phelps S, Duffy D, Thompson PJ. Polymorphisms in the 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (ALOX5AP) gene are not associated with asthma in an Australian population. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35:332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SH, Bae JS, Suh CH, Nahm DH, Holloway JW, Park HS. Polymorphism of tandem repeat in promoter of 5-lipoxygenase in ASA-intolerant asthma: a positive association with airway hyperresponsiveness. Allergy 2005;60:760–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drouin SM, Corry DB, Kildsgaard J, Wetsel RA. Cutting edge: the absence of C3 demonstrates a role for complement in Th2 effector functions in a murine model of pulmonary allergy. J Immunol 2001;167:4141–4145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes KC, Grant AV, Baltadzhieva D, Zhang S, Berg T, Shao L, Zambelli-Weiner A, Anderson W, Nelsen A, Pillai S, et al. Variants in the gene encoding C3 are associated with asthma and related phenotypes among African Caribbean families. Genes Immun 2006;7:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa K, Tamari M, Shao C, Shimizu M, Takahashi N, Mao XQ, Yamasaki A, Kamada F, Doi S, Fujiwara H, et al. Variations in the C3, C3a receptor, and C5 genes affect susceptibility to bronchial asthma. Hum Genet 2004;115:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spira A, Beane J, Shah V, Liu G, Schembri F, Yang X, Palma J, Brody JS. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:10143–10148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schutyser E, Richmond A, Van Damme J. Involvement of CC chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18) in normal and pathological processes. J Leukoc Biol 2005;78:14–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Nadai P, Charbonnier AS, Chenivesse C, Senechal S, Fournier C, Gilet J, Vorng H, Chang Y, Gosset P, Wallaert B, et al. Involvement of CCL18 in allergic asthma. J Immunol 2006;176:6286–6293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N, et al. Irf-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon–dependent immune responses. Nature 2005;434:772–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burch LH, Yang IV, Whitehead GS, Chao FG, Berman KG, Schwartz DA. The transcriptional response to lipopolysaccharide reveals a role for interferon-γ in lung neutrophil recruitment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L677–L682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes PJ. Targeting the epigenome in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009;6:693–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Eerdewegh P, Little RD, Dupuis J, Del Mastro RG, Falls K, Simon J, Torrey D, Pandit S, McKenny J, Braunschweiger K, et al. Association of the ADAM33 gene with asthma and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Nature 2002;418:426–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ceyhan BB, Karakurt S, Hekim N. Plasma adrenomedullin levels in asthmatic patients. J Asthma 2001;38:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohno M, Hanehira T, Hirata K, Kawaguchi T, Okishio K, Kano H, Kanazawa H, Yoshikawa J. An accelerated increase of plasma adrenomedullin in acute asthma. Metabolism 1996;45:1323–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.