Abstract

Parvoviruses are small single-stranded DNA viruses that are ubiquitous in nature. Infections with both autonomous and helper-virus dependent parvoviruses are common in both human and animal populations, and many animals are host to a number of different parvoviral species. Despite the epidemiological importance of parvoviruses, the presence and role of genome recombination within or among parvoviral species has not been well characterized. Here we show that natural recombination may be widespread in these viruses. Different genome regions of both porcine parvoviruses and Aleutian mink disease viruses have conflicting phylogenetic histories, providing evidence for recombination within each of these two species. Further, the rodent parvoviruses show complex evolutionary histories for separate genomic regions, suggesting recombination at the interspecies level.

Parvoviruses infect a diverse array of hosts. These small DNA viruses can be autonomous or depend upon a larger helper-virus for replication. Among the parvoviruses that infect vertebrate hosts there are currently five recognized genera. Members of the Parvovirus, Bocavirus, Amdovirus and Erythrovirus genera are all autonomous and can be found in humans, dogs, cats, cows, pigs, rodents and a number of other mammals. Indeed, the recent emergence of canine parvovirus (CPV2) from feline parvovirus (FPV) constitutes a valuable model of a successful cross-species transmission event (reviewed by Parrish & Kawaoka, 2005). Analyses of nucleotide substitution rates have also suggested that parvoviruses evolve far more rapidly than other (larger) DNA viruses, although the reasons for this remain unclear (Shackelton et al., 2005; Pereira et al., 2007).

The severity of parvovirus disease varies greatly. Some parvoviruses, such as human B19 virus and the rodent parvoviruses, usually cause mild disease (Young & Brown, 2004; Jacoby et al., 1995). Animals infected with Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (ADV), however, may show a variety of symptoms, ranging from subclinical to chronic disease and death, with more severe disease in susceptible genotypes (Jackson et al., 1996). Porcine parvovirus (PPV) causes little clinical disease in adults, but infection of pregnant females results in infection of the immunologically tolerant fetus, leading to reproductive complications such as fetal death and abortion (Brown et al., 1980; Mengeling & Cutlip, 1975).

Parvoviral genomes are composed of a linear single-stranded segment of DNA approximately 5 kb in length. The two primary ORFs, the 3′ nonstructural ‘NS’ ORF and the 5′ structural ‘VP’ ORF each encode at least two proteins. Hairpin structures, necessary for priming replication, are found in the non-translated regions at both ends of the genome, bordering the ORFs. Genomic replication takes place in the nucleus of actively dividing cells and utilizes cellular machinery, including subunits of the cellular polymerase. As the virus cannot induce mitosis, it replicates primarily in rapidly dividing cells, which may be in a variety of tissues depending on the age of the host and the tropism of the virus. Replication requires a double-stranded template and occurs through a rolling hairpin mechanism where the imperfect palindromes located in the 3′ and 5′ ends of the genome are used to assemble concatameric virus templates. Nicking by the viral NS1 protein and strand exchange are involved in the resolution of dimeric or tetrameric DNA replication intermediates (Cotmore & Tattersall, 2003).

The antibody-mediated immune response against parvoviruses appears to be quite effective in many hosts and in the case of CPV2, FPV, PPV and B19 the virus is generally cleared within a few days of the response developing. However, other parvoviruses, including ADV and probably many rodent parvoviruses, are not cleared despite the strong immune response that they elicit (Alexandersen et al., 1988; Porter, 1986). For example, some rodent parvoviruses persist in the kidneys and are shed in the urine over long periods (Jacoby et al., 1996). In the case of B19, persistent viral DNA can be detected by PCR years after the initial infection, although it is not clear whether the virus is still replicating over that period (Manning et al., 2007; Lefrere et al., 2005). Finally, persistent viral shedding has also been found in PPV infections (Guérin & Pozzi, 2005).

While there is a growing body of work on the mechanisms of replication and the dynamics of evolutionary change in parvoviruses, little is known about the occurrence or characteristics of parvoviral recombination in nature. However, parvovirus replication would appear to provide opportunities for recombination if a cell is co-infected by two different genomes. Indeed, the ubiquitous nature of the parvoviruses means that co-infection may be commonplace, and in many cases DNA from more than one virus strain is seen in an individual animal (Norja et al., 2006), allowing for the possibility of recombination.

Recombination is an important evolutionary mechanism in many virus families, having the potential to combine beneficial mutations within a single genome, and similarly, to decouple advantageous mutations from deleterious genomic baggage (Awadalla, 2003). Recombination has been observed for a number of DNA virus families, including the herpesviruses, the poxviruses, the single-stranded DNA geminiviruses and the anelloviruses (Fleischmann, 1996; Thiry et al., 2005; Bugert & Darai, 2000; Monci et al., 2002; Hino & Miyata, 2007). However, neither the frequency nor determinants of recombination among the parvoviruses are known. During mixed infection in cell culture recombination can be seen among parvovirus genomes. This can generate altered forms that may give rise to replicating genomes, as seen in studies using mixtures of DNAs for the production of gene therapy vectors derived from adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) or some autonomous parvoviruses (Allen et al., 1997; Brandenburger & Velu, 2004). Furthermore, extensive recombination was inferred as the explanation for the presence of mosaic genomes that arose during the passaging of a CPV2 strain in tissue culture (Badgett et al., 2002). There is, however, less evidence for recombination among parvovirus genomes recovered from natural infections, although an analysis of mice, hamster, and LuIII parvovirus genomes that examined the phylogenies of ORFs 1 and 2 separately revealed different evolutionary histories for each ORF, indicative of recombination (Lukashov & Goudsmit, 2001). Similarly, incongruencies were observed in the phylogenetic trees of ORFs 1 and 2 of the AAVs, with respect to AAV2 and AAV4 (Lukashov & Goudsmit, 2001).

Herein, we analyse three groups of autonomous parvoviruses for evidence of recombination either within or among species. We focus on PPV, ADV and the rodent parvoviruses as there is a substantial amount of information available about these viruses, along with relatively long and diverse nucleotide sequences which facilitates the in silico examination of recombination frequency. Viral sequences were compiled from GenBank and aligned by eye or with MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004; sequence alignments are available as supplementary information with the online version of this paper). Isolate names, year, and location of isolation, where available, were provided either on GenBank or by Zimmermann et al. (2006). GenBank accession numbers are as follows. PPV: VRI-1, AY390557; Challenge, AY684866; SR-1, DQ675456; Kresse, U44978; PPV_NADL-2, NC_001718; China-318, AY583318; 15a, AY684865; 27a, AY684871; 21a, AY684868; 225b, AY684864; PPV/Tornau, AY684869; 143a, AY684867; vaccine_IDT, AY684872; 106b, AY684870. ADV: V3, DQ630715; V9, DQ630716; M15, DQ630719; M19, DQ630721; M21, DQ630722; Far East, DQ371395; TH5, AF124791; TR, AMU39013; Pullman, AMU39014; Utah 1 kit, AMU39015; MDPMVT6, M63044; MDPMVT7, M63045; Utah 1, M32981; SL-3, X97629; ADV-G, NC_001662. Rodent parvoviruses (using standardized nomenclature; Besselsen et al., 2006): LuIII virus (LuIII), NC_004713; Minute virus of mice ‘prototype’ (MVMp), NC_001510; MVM immunosuppressive variant (MVMi), X02481; MVMm, DQ196317; MVMc, MVU34256; mouse parvovirus 1a (MPV-1a), NC_001630; MPV-1e, DQ898166; MPV-1c, MOU34254; MPV-1b, MOU34253; MPV-2, NC_008186; MPV-3, NC_008185; hamster parvovirus (HaPV), HOU34255.

To screen for recombination we employed two preliminary detection programs: RDP2 (Martin et al., 2005) and Genetic Algorithms for Recombination Detection (GARD; Kosakovsky Pond et al., 2006). The former includes six separate recombination detection programs—Bootscan, Chimeric, GENECONV, MaxChi, RDP, and SiScan—which were employed with their default parameters (and the following general options: window size of 20, linear sequences, Bonferroni correction, finding consensus daughter sequences, and polishing breakpoints). General parameter settings were used for GARD (GTR model of nucleotide substitution and Beta-Gamma rate variation with 3 rate classes). To exclude the possibility of false-positive recombination detection, putative recombinant regions were considered only if three or more different programs detected recombination within the same general region of the alignment. We then separated the alignments at a point within the region, estimated maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees for the individual sections, and compared their evolutionary histories. MODELTEST (Posada & Crandall, 1998) was used to determine the most appropriate models of nucleotide substitution, which were then used as the basis of phylogenetic inference using the ML method available in PAUP★ (Swofford, 2003). The selected model (TVM+I in the case of the PPV and GTR+I+Γ in the case of ADV and the mouse/hamster/LuIII parvoviruses) was used in the ML analysis of all sections of the alignment. In each case, support for tree nodes was determined with neighbour-joining bootstrap resampling (based on 1000 replicates). Only nodes with ≥70 % bootstrap support were considered.

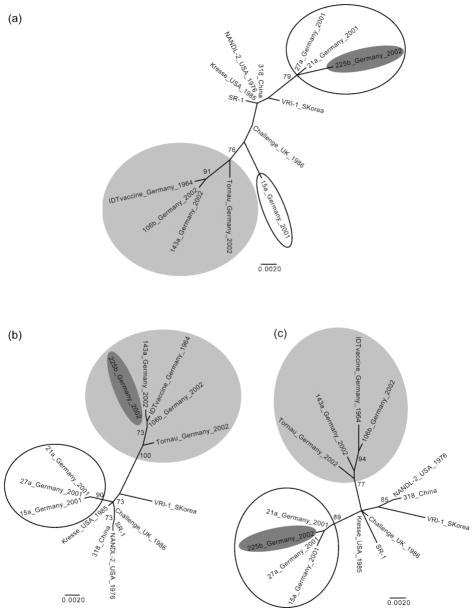

For PPV we constructed a 2620 bp alignment (corresponding to base pairs 1990–4609 of reference genome NC_001718), which includes a C-terminal part of the NS1 gene sequence and the entire VP1 ORF. Putative recombination regions were located around sites 563 and 1730 of our alignment. Phylogenetic trees of the sections bordered by these points did, indeed, show significant phylogenetic incongruence (Fig. 1). In particular, isolate 225b, collected by Zimmermann et al. (2006) in Germany, appears to be a recombinant between two distinct genetic groups circulating in that country. In addition, isolate 15a may have been involved in a recombination event.

Fig. 1.

PPV phylogenies. Separate phylogenetic trees were inferred for nucleotides (a) 1–562, (b) 563–1729 and (c) 1730–2620 of the alignments. Viruses isolated from Germany in 2001, which generally form a tight clade, are outlined in black. Viruses isolated from Germany in 2002, along with a vaccine strain from 1964, which consistently form a clade, are labelled in light grey. Isolate 225b is in dark grey. Nodes with ≥70 % bootstrap support are shown and branch lengths are scaled according to nucleotide substitutions per site.

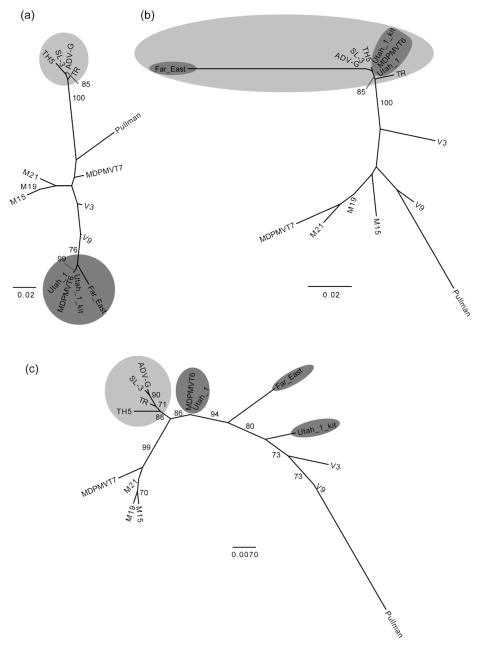

An adequate alignment could only be obtained for a 1533 bp portion of the ADV VP2 gene (reference genome NC_001662 positions 2643–4175). Putative recombination regions were located near nucleotides 543 and 1051 of our alignment. Cutting the alignment at these points and constructing separate phylogenies for each section again resulted in incongruent tree topologies (Fig. 2). Although the bootstrap support for many of the nodes is below 70 %, there is sufficient resolution to show significant incongruencies, especially with regard to clades TH5/SL-3/ADV-G/TR and Utah 1/MDPMVT6/Utah 1 kit/Far East.

Fig. 2.

ADV phylogenies. Separate phylogenetic trees were inferred for nucleotides (a) 1–542, (b) 543–1050, and (c) 1051–1533. The two groups that show significant changes in topology, with respect to each other, are shaded in light and dark grey. Nodes with ≥70 % bootstrap support are shown and branch lengths are scaled according to nucleotide substitutions per site.

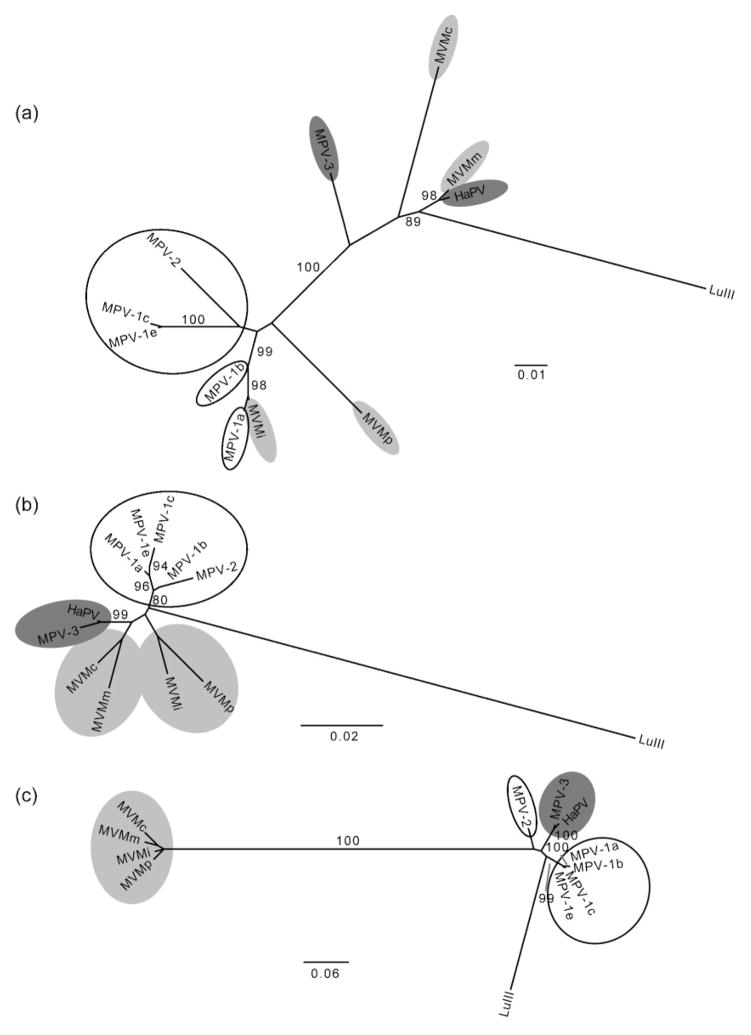

Almost full-length rodent parvovirus genome sequences were analysed for recombination, and preliminary phylogenetic comparisons suggested frequent recombination among the mouse parvoviruses (MPVs), Minute viruses of mice (MVMs), LuIII virus and hamster parvovirus (HaPV). Therefore, we focused on these viruses and not the rat parvoviruses, which did not provide clear evidence of recombination. The former viruses were aligned (reference genome NC_001630 positions 144–4728) and analysed as described above. A number of putative breakpoints were estimated, some of which were located in regions around positions 855 and 2227 of our alignment. Phylogenies of the sections bordered by these positions show several topological inconsistencies (Fig. 3). For example, among other differences, HaPV and MPV-3 are very closely related in all but the first part of their genomes; most MPVs show relatively close relationships with some MVMs in the first part of their genomes but the two groups are clearly distinct in the second half of their genomes, and LuIII shows unique relationships to each of these groups in different genome regions.

Fig. 3.

Rodent parvovirus phylogenies. Phylogenetic trees were inferred for nucleotides (a) 1–854, (b) 855–2226 and (c) 2227–4654. Groups of viruses are shaded or outlined for ease of visualization: MVMs are light grey; HaPV and MPV-3 are dark grey; all MPVs except MPV-3 are circled in black; and LuIII virus is unmarked. Nodes with ≥70 % bootstrap support are shown and branch lengths are scaled according to nucleotide substitutions per site.

While the complexity of recombination in these viruses means that we are unlikely to have identified exact breakpoints of recombination, we have demonstrated that different sections of the genomes have conflicting phylogenetic histories, indicating that recombination may be a relatively common event within and/or among these parvoviral species. Given the differences in epidemiology, cell tropism, pathogenicity and host species, many of which are not fully understood, the specifics of recombination and the evolutionary forces acting on any recombinants are likely to differ among these and other parvoviruses.

The initial requirements for recombination include co-infection of the same animal and host cell. High seroprevalences of MVMs and MPVs are reported for wild mice populations, and in many cases mice go on to develop persistent infections with chronic shedding of the virus from the kidneys (Becker et al., 2007; Jacoby et al., 2000). This suggests the potential for frequent co-infection, although the exact frequencies or likelihood of mixed infections are not known. High population densities and contact frequencies of rodents may explain, in part, why evidence of recombination has been readily observed both here and previously (Lukashov & Goudsmit, 2001) among different viral species infecting these populations. In humans, the frequent detection of persistent erythroviral DNA and multiple genotypes also suggests co-infection and opportunities for recombination (Hokynar et al., 2002; Parsyan et al., 2007). Likewise, multiple strains of AAV infect humans and more than one genotype can be found in an individual (Gao et al., 2004). In experimental studies, the viral sequences recovered from ADV-infected mink contained multiple genotypes, suggesting that mixed infections may be common (Gottschalck et al., 1994, 1991), although the degree of sequence variation and population structures of the viruses in natural infections have not been examined in detail. Little is known about the epidemiology of PPV, the likelihood of multiple infections, or the possible selection pressures acting on recombinant viruses. However, high densities and contact rates as well as crowding effects in intensively reared pig populations, along with partial herd immunity, might provide ready opportunities for recombination. The recombination of the PPV genome seen in this study involves viruses that differ antigenically, suggesting that immune pressure may have played a role in the emergence of the recombinant strain (Zimmermann et al., 2006; Zeeuw et al., 2007). It seems that all of the viruses examined here may, under certain circumstances, persist in the host. As this may increase the likelihood of recombination, it will be informative to examine the occurrence and relative frequency of recombination in those acute parvoviruses which are cleared by the host within a few days.

Parvoviruses have shown an ability to emerge in new hosts (Parrish & Kawaoka, 2005). Recombination or segmental reassortment has been reported for a number of other viruses during the processes of shifting host ranges; whether recombination would increase the likelihood of the emergence of parvoviruses in new hosts must be addressed in more depth. This uncertainty notwithstanding, our analysis suggests that, along with relatively rapid rates of sequence variation, co-infection and subsequent recombination may be important forces in the natural evolution of parvoviruses. As population densities and contact frequencies between and among humans and wild or agricultural animals continue to increase, it seems inevitable that recombination will be an important factor, among others, in the emergence of new viral genotypes and species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant number GM080533-01.

Footnotes

Sequence alignments are available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Alexandersen S, Bloom ME, Wolfinbarger J. Evidence of restricted viral replication in adult mink infected with Aleutian disease of mink parvovirus. J Virol. 1988;62:1495–1507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1495-1507.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JM, Debelak DJ, Reynolds TC, Miller AD. Identification and elimination of replication-competent adeno-associated virus (AAV) that can arise by nonhomologous recombination during AAV vector production. J Virol. 1997;71:6816–6822. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6816-6822.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla P. The evolutionary genomics of pathogen recombination. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:50–60. doi: 10.1038/nrg964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MR, Auer A, Carmichael LE, Parrish CR, Bull JJ. Evolutionary dynamics of viral attenuation. J Virol. 2002;76:10524–10529. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10524-10529.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SD, Bennett M, Stewart JP, Hurst JL. Serological survey of virus infection among wild house mice (Mus domesticus) in the UK. Lab Anim. 2007;41:229–238. doi: 10.1258/002367707780378203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besselsen DG, Romero MJ, Wagner AM, Henderson KS, Livingston RS. Identification of novel murine parvovirus strains by epidemiological analysis of naturally infected mice. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1543–1556. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger A, Velu T. Autonomous parvovirus vectors: preventing the generation of wild-type or replication-competent virus. J Gene Med. 2004;6:S203–S211. doi: 10.1002/jgm.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TT, Jr, Paul PS, Mengeling WL. Response of conventionally raised weanling pigs to experimental infection with a virulent strain of porcine parvovirus. Am J Vet Res. 1980;41:1221–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugert JJ, Darai G. Poxvirus homologues of cellular genes. Virus Genes. 2000;21:111–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Resolution of parvovirus dimer junctions proceeds through a novel heterocruciform intermediate. J Virol. 2003;77:6245–6254. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6245-6254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann WJ. In: Medical Microbiology. 4. Baron S, editor. Galveston, TX: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, Wilson JM. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalck E, Alexandersen S, Cohn A, Poulsen LA, Bloom ME, Aasted B. Nucleotide sequence analysis of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus shows that multiple virus types are present in infected mink. J Virol. 1991;65:4378–4386. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4378-4386.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalck E, Alexandersen S, Storgaard T, Bloom ME, Aasted B. Sequence comparison of the non-structural genes of four different types of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus indicates an unusual degree of variability. Arch Virol. 1994;138:213–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01379127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin B, Pozzi N. Viruses in boar semen: detection and clinical as well as epidemiological consequences regarding disease transmission by artificial insemination. Theriogenology. 2005;63:556–572. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino S, Miyata H. Torque teno virus (TTV): current status. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:45–57. doi: 10.1002/rmv.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokynar K, Soderlund-Venermo M, Pesonen M, Ranki A, Kiviluoto O, Partio EK, Hedman K. A new parvovirus genotype persistent in human skin. Virology. 2002;302:224–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MK, Ellis LC, Morrey JD, Li ZZ, Barnard DL. Progression of Aleutian disease in natural and experimentally induced infections of mink. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:1753–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby RO, Johnson EA, Ball-Goodrich L, Smith AL, McKisic MD. Characterization of mouse parvovirus infection by in situ hybridization. J Virol. 1995;69:3915–3919. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3915-3919.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby RO, Ball-Goodrich LJ, Besselsen DG, McKisic MD, Riley LK, Smith AL. Rodent parvovirus infections. Lab Anim Sci. 1996;46:370–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby RO, Johnson EA, Paturzo FX, Ball-Goodrich L. Persistent rat virus infection in smooth muscle of euthymic and athymic rats. J Virol. 2000;74:11841–11848. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11841-11848.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosakovsky Pond SL, Posada D, Gravenor MB, Woelk CH, Frost SD. Automated phylogenetic detection of recombination using a genetic algorithm. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1891–1901. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrere JJ, Servant-Delmas A, Candotti D, Mariotti M, Thomas I, Brossard Y, Lefrere F, Girot R, Allain JP, Laperche S. Persistent B19 infection in immunocompetent individuals: implications for transfusion safety. Blood. 2005;106:2890–2895. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashov VV, Goudsmit J. Evolutionary relationships among parvoviruses: virus-host coevolution among autonomous primate parvoviruses and links between adeno-associated and avian parvoviruses. J Virol. 2001;75:2729–2740. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2729-2740.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A, Willey SJ, Bell JE, Simmonds P. Comparison of tissue distribution, persistence, and molecular epidemiology of parvovirus B19 and novel human parvoviruses PARV4 and human bocavirus. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1345–1352. doi: 10.1086/513280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Williamson C, Posada D. RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:260–262. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengeling WL, Cutlip RC. Pathogenesis of in utero infection: experimental infection of five-week-old porcine fetuses with porcine parvovirus. Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:1173–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monci F, Sanchez-Campos S, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. A natural recombinant between the geminiviruses Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus exhibits a novel pathogenic phenotype and is becoming prevalent in Spanish populations. Virology. 2002;303:317–326. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norja P, Hokynar K, Aaltonen LM, Chen R, Ranki A, Partio EK, Kiviluoto O, Davidkin I, Leivo T, et al. Bioport-folio: lifelong persistence of variant and prototypic erythrovirus DNA genomes in human tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7450–7453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602259103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish CR, Kawaoka Y. The origins of new pandemic viruses: the acquisition of new host ranges by canine parvovirus and influenza A viruses. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:553–586. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsyan A, Szmaragd C, Allain JP, Candotti D. Identification and genetic diversity of two human parvovirus B19 genotype 3 subtypes. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:428–431. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira CA, Leal ES, Durigon EL. Selective regimen shift and demographic growth increase associated with the emergence of high-fitness variants of canine parvovirus. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter DD. Aleutian disease: a persistent parvovirus infection of mink with a maximal but ineffective host humoral immune response. Prog Med Virol. 1986;33:42–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelton LA, Parrish CR, Truyen U, Holmes EC. High rate of viral evolution associated with the emergence of carnivore parvovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:379–384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406765102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. PAUP★: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (★and other methods) Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thiry E, Meurens F, Muylkens B, McVoy M, Gogev S, Thiry J, Vanderplasschen A, Epstein A, Keil G, Schynts F. Recombination in alphaherpesviruses. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:89–103. doi: 10.1002/rmv.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NS, Brown KE. Parvovirus B19. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:586–597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeuw EJ, Leinecker N, Herwig V, Selbitz HJ, Truyen U. Study of the virulence and cross-neutralization capability of recent porcine parvovirus field isolates and vaccine viruses in experimentally infected pregnant gilts. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:420–427. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Ritzmann M, Selbitz HJ, Heinritzi K, Truyen U. VP1 sequences of German porcine parvovirus isolates define two genetic lineages. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:295–301. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.