Abstract

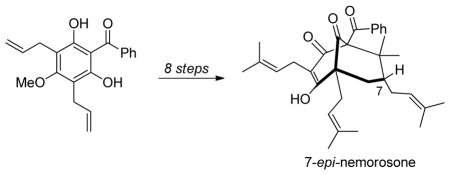

A concise total synthesis of (±)-7-epi-nemorosone is reported. Our synthetic approach establishes a viable route to polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol natural products (PPAP’s) bearing a C-7 endo prenyl sidechain. Key steps include retro-aldol-vinyl cerium addition to a hydroxy adamantane core scaffold and palladium-mediated deoxygenation.

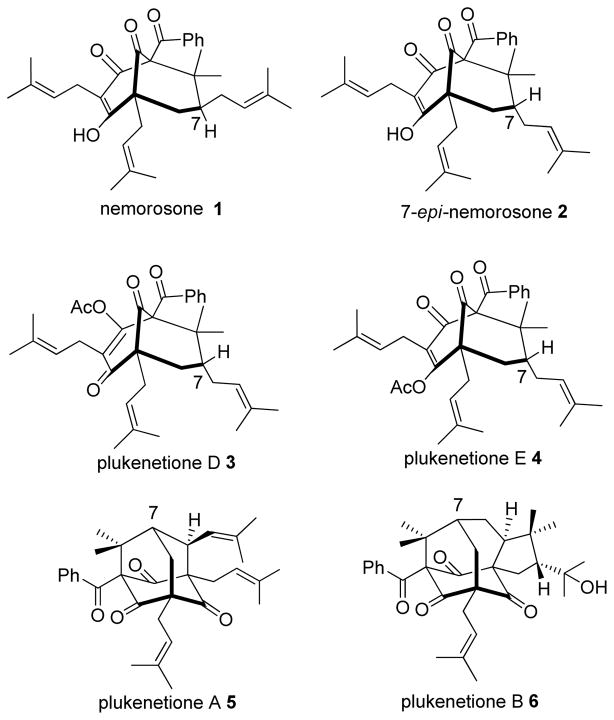

Polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol natural products (PPAP’s) are a class of compounds that have attracted significant attention in the synthetic chemistry community, largely due to their challenging structures and biological activities.1 PPAP’s generally possess a bicyclo [3.3.1] nonane-1, 3, 5-trione core structure which is comprised of a highly oxygenated framework and vicinal quaternary carbon centers (Figure 1). Recent biological studies have showed promising results for PPAP’s. For example, nemorosone (1) and its C-7 epimer 7-epi-nemorosone (2) both show antibacterial activity2 and potent activity against the malaria parasite P. falciparum. 3 In addition, (1) and (2) exhibit cytotoxicity against a number of human cancer cell lines4 including breast, colon, brain, ovary, liver, and lung carcinomas.5 Recently, nemorosone (1) was found to be a potent protonophoric mitochondrial uncoupler which may form the basis of its cytotoxicity to cancer cells.6

Figure 1.

Representative Type A Polycyclic Polyprenylated Acylphloroglucinols (PPAP’s)

The type A7 PPAP nemorosone (1) has a C-7 exo prenyl moiety whereas 7-epi-nemorosone (2) bears a C-7 endo-prenyl substituent. The O-methyl ether of 2 was first isolated by Marsaioli and coworkers in 19998 but was assigned as an isomeric structure. In 1999, Jacobs and coworkers reported the isolation of the enol ester isomers plukenetiones D and E (3 and 4). These compounds were found to have the same framework as nemorosone but the C-7 stereocenter was unassigned.9 In 2000, Jacobs and Grossman10 analyzed NMR data for 3 and 4 and proposed that these compounds were enol acetates of 7-epi-nemorosone (2). Subsequently, Marsaioli and coworkers reisolated the compound and corrected its structure to 2. 11 Despite numerous synthetic efforts concerning type A PPAPs,12 few have targeted construction of the C-7 endo prenyl moiety as found in 2 with the exception of a recent successful example reported by Plietker and coworkers.12 l Herein, we report the first total synthesis of (±)-7-epi-nemorosone (2) via elaboration of a hydroxy adamantane core scaffold. 13

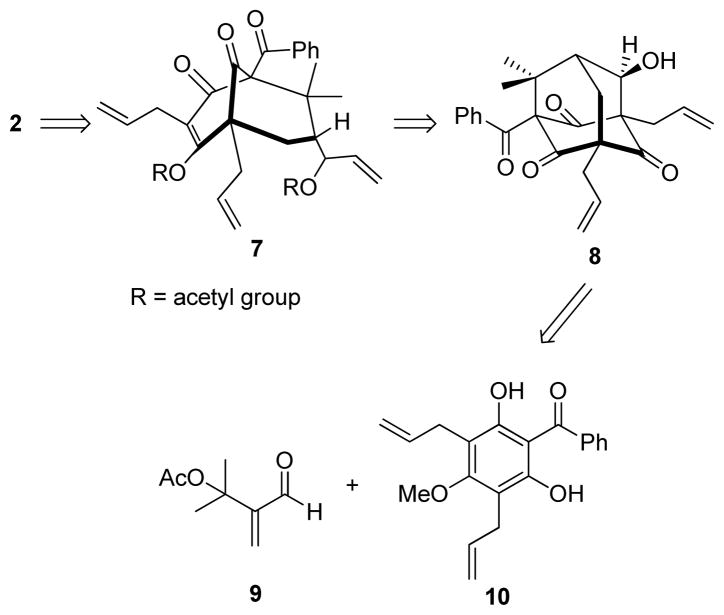

Retrosynthetically, we envisioned that 7-epi-nemorosone (2) may be derived from the bis-O-acylated bicyclo [3.3.1] nonane 7 after palladium(0)-mediated reduction (Figure 2). Bicyclic intermediate 7 may be derived from organocerium-mediated retro-aldol/vinyl metal addition to adamantane alcohol 8.13 Finally, adamantane 8 may be obtained from the readily available α-acetoxy enal 9 and acylphloroglucinol 10 using an alkylative dearomatization-annulation sequence.13

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis for (±)-7-epi-nemorosone 2

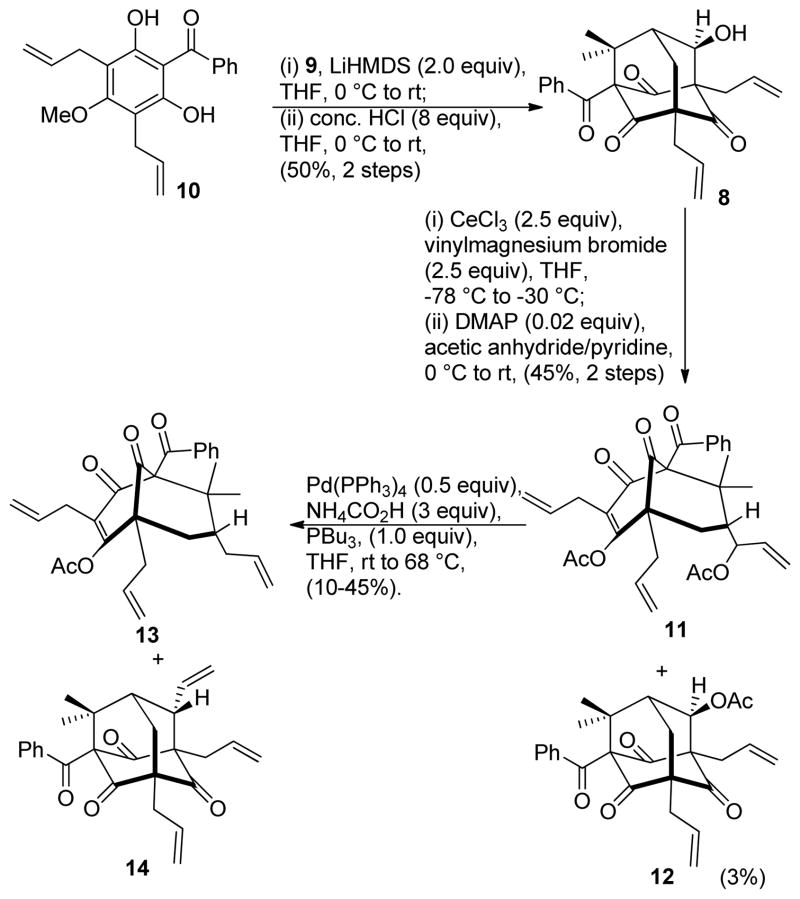

The synthesis commenced with treatment of acylphloroglucinol 10 with aldehyde 9 under basic conditions to afford the dearomatized adduct in high yield.13 (Scheme 1) The crude product was directly subjected to acidic conditions (conc. HCl, THF, rt) to yield adamantane alcohol 8 (50% yield, two steps).13 Exposure of adamantane 8 to a pre-activated CeCl3/vinylmagnesium bromide mixture led to tandem retro-aldol condensation / Grignard addition.14 The crude product mixture was subjected to standard esterification conditions (Ac2O/pyridine/DMAP) which afforded bis-acylated compound 11 as the major product (45% yield, two steps). A small amount of adamantane acetate 12 was also isolated in 3% yield via acylation of unreacted adamantane alcohol 8.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the 7-epi-nemorosone core

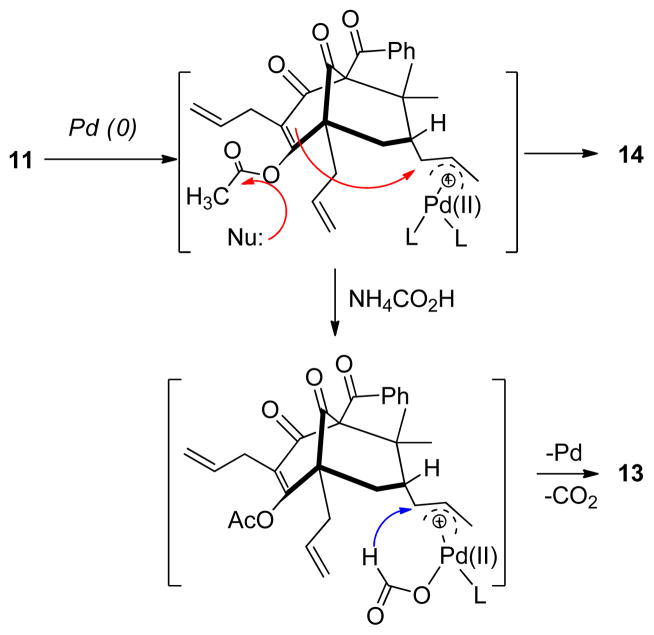

Efforts to convert the bis-acetate 11 to its reduced form 13 were problematic as a competing pathway leading to the formation of the undesired adamantane 14 was generally observed. This can presumably be attributed to a facile intramolecular cyclization which occurred prior to reduction (Scheme 2). After evaluation of reaction conditions including palladium (0) and hydride sources,15 an optimized yield (45%) for 13 was obtained using Pd(Ph3P)4 with added PBu315c using NH4CO2H at 68 °C and a reaction concentration of 0.2 M. A relatively high Pd(0) catalyst loading (50%) was found to be necessary to reduce the reaction time and avoid decomposition of product 13 under the reaction conditions. In addition, under these conditions adamantane product 14 was also produced (~10%). Finally, alkene cross metathesis of 13 with isobutylene catalyzed by the Grubbs II catalyst16 afforded plukenetione E acetate (4) albeit in inconsistent yield, likely due to cleavage of the labile enol acetate protecting group under thermal conditions.17 Analytical data for synthetic 4 were in agreement with the data reported by Jacobs and coworkers.9,17

Scheme 2.

Cyclization vs. Reduction Processes

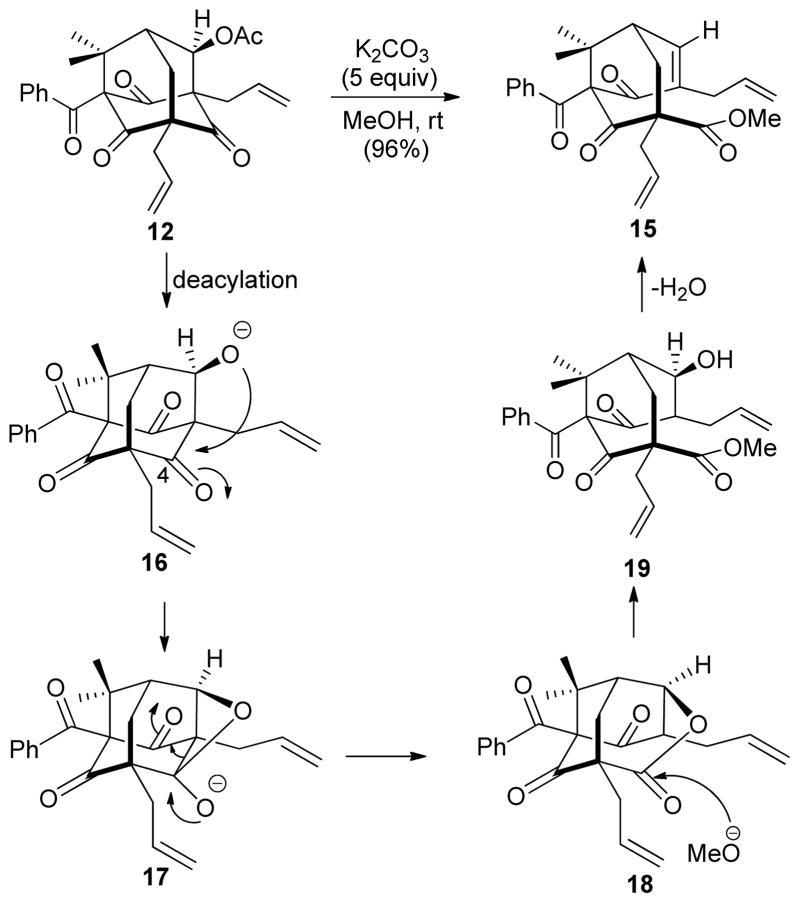

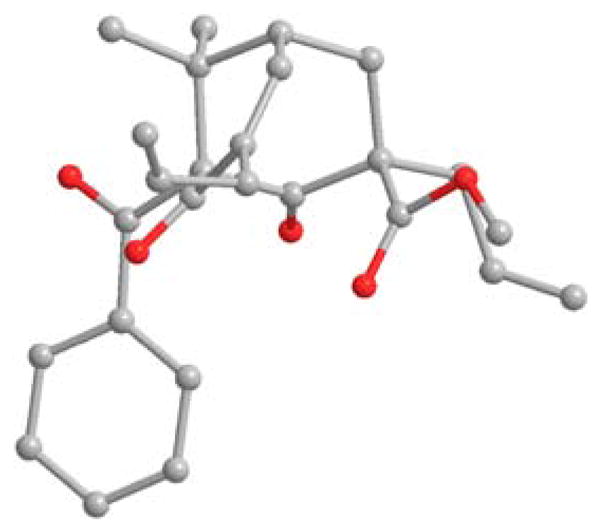

Interestingly, treatment of acylated adamantane 12 with K2CO3/MeOH led to unexpected formation of the fragmentation product 15 in nearly quantitative yield. The structure of 15 was confirmed by X-ray analysis (Figure 3).17 A proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 3. Adamantane acetate 12 may be initially deacylated by methoxide to generate alkoxide 16. The proximity between the emerged alkoxide and C-4 ketone (~2.9 Ǻ) should facilitate formation of the oxetane intermediate 17. Fragmentation of 17 followed by protonation may then lead to formation of lactone 18 which may subsequently undergo ring-opening by methoxide to afford 19. Finally, dehydration of alcohol 19 via β-elimination may afford bicyclic product 15. A similar fragmentation process was reported by Nicolaou and coworkers enroute to the PPAP natural product hyperforin.18

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure of fragmentation product 15

Scheme 3.

An Unexpected Fragmentation Process

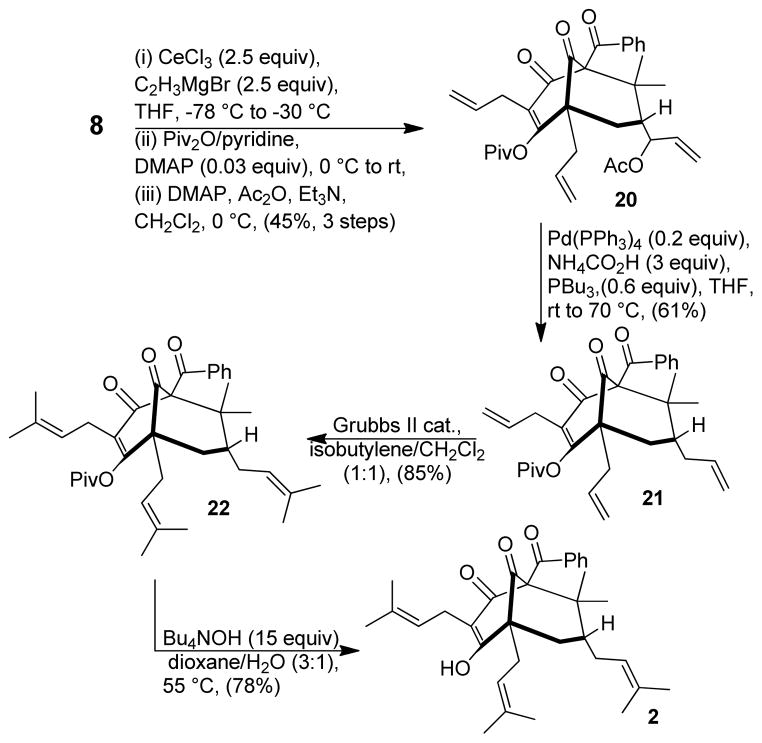

Due to inconsistent yields observed for reduction of 11 and in the cross metathesis of derived product 13, we considered altering the protecting group for the vinylogous acid moiety in order to increase its stability. After considerable experimentation, we found the pivalate group to be an excellent candidate for the sequence. Starting from adamantane 8, tandem retro-aldol/vinyl Grignard addition followed by sequential acylations led to the formation of 20 (45% yield, 3 steps) as a single enol pivalate17,19 isomer with only a single purification required (Scheme 4). Palladium-mediated deoxygenation of 20 occurred smoothly to generate 21 in consistent overall yield (61%). Moreover, due to the increased stability of the pivalate protecting group, adamantane byproduct 14 (cf. Scheme 1) was not observed.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of (±)-7-epi-nemorosone

In the final stages of the synthesis, global cross metathesis of 21 afforded the triprenylated 7-epi-nemorosone core structure 22 in high yield (Scheme 4). Tetrabutylammonium hydroxide-mediated deprotection of 22 effected removal of the pivalate protecting group affording the natural product 2. Attempted purification of the crude product mixture via conventional silica gel chromatography led to unexpected decomposition of 2.12d,h Fortunately, purification of synthetic 2 using preparative HPLC was successful employing 99:1 CH3CN: H2O = with 0.01% TFA20 in the eluant buffer leading to the production of (±)-7-epi-nemorosone (2) (78%). Analytical data including 1H and 13C NMR analyses for 2 were in agreement with those obtained from a sample provided by the Jacobs group.

In conclusion, we have achieved the first total synthesis of (±)-7-epi-nemorosone, a type A PPAP natural product bearing a C-7 endo prenyl sidechain. Key steps include retro-aldol-vinyl cerium addition to a hydroxy adamantane core structure and palladium-mediated deoxygenation. The use of an enol pivalate protecting group for a vinylogous acid moiety was found to be helpful in order to prevent undesirable cyclizations. Further studies on the synthesis of PPAP’s and their chemical reactivity are ongoing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (GM-073855) and the National Science Foundation (0848082) for research support. We thank Professors John Snyder and Aaron Beeler, and Dr. Ji Qi, Dr. Paul Ralifo, Dr. Dana Winter, Dr. Melissa Dominguez, and Jonathan Boyce (Boston University) for helpful discussions. We also thank Prof. Helen Jacobs (University of West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica) for providing a natural sample of 7-epi-nemorosone.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.For a recent review of synthetic efforts toward PPAP’s, see: Njardarson JT. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:7631. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.079.

- 2.de Castro Ishida VF, Negri G, Salatino A, Bandeira MFCL. Food Chem. 2011;125:966. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monzote L, Cuesta-Rubio O, Matheeussen A, Van Assche T, Maes L, Cos P. Phytother Res. 2011;25:458. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuesta-Rubio O, Frontana-Uribe BA, Ramírez-Apan T, Cárdenas J. Z Naturforsch. 2002;57c:372. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-3-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Díaz-Carballo D, Malak S, Bardenheuer W, Freistuehler M, Reusch HP. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:9635. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Popolo A, Piccinelli AL, Morello S, Sorrentino R, Osmany CR, Rastrelli L, Aldo P. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89:50. doi: 10.1139/y10-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Pardo-Andreu GL, Nuñez-Figueredo Y, Tudella VG, Cuesta-Rubio O, Rodrigues FP, Pestana CR, Uyemura SA, Leopoldino AM, Alberici LC, Curti C. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:255. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holtrup F, Bauer A, Fellenberg K, Hilger RA, Wink M, Hoheisel JD. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1045. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciochina R, Grossman RB. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3963. doi: 10.1021/cr0500582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Oliveira CMA, Porto ALM, Bittrich V, Marsaioli AJ. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:1073. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds WF, McLean S, Carrington CMS, Jacobs H, Henry GE. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:1581. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman RB, Jacobs H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;27:5165. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bittrichb V, Amaralb MCE, Machado SMF, Anita J, Marsaioli AJ. Z Naturforsch. 2003;58:643. doi: 10.1515/znc-2003-9-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For select, recent syntheses of PPAP’s, see: Kuramochi A, Usuda H, Yamatsugu K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14200. doi: 10.1021/ja055301t.Siegel DR, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1048. doi: 10.1021/ja057418n.Rodeschini V, Ahmad NM, Simpkins NS. Org Lett. 2006;8:5283. doi: 10.1021/ol0620592.Tsukano C, Siegel DR, Danishefsky SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703886.Nuhant P, David M, Pouplin T, Delpech B, Marazano C. Org Lett. 2007;9:287. doi: 10.1021/ol062736s.Qi J, Porco JA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12682. doi: 10.1021/ja0762339.Shimizu Y, Shi S, Usuda H, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:1103. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906678.Simpkins N, Taylor J, Weller M, Hayes C. Synlett. 2010;4:639.Qi J, Beeler AB, Zhang Q, Porco JA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13642. doi: 10.1021/ja1057828.Garnsey MR, Lim D, Yost JM, Coltart DM. Org Lett. 2010;12:5234. doi: 10.1021/ol1022728.McGrath NA, Binner JR, Markopoulos G, Brichacek M, Njardarson JT. Chem Commun. 2011;47:209. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01419b.Biber N, Möws K, Plietker B. Nat Chem. 2011;9:938. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1170.Garnsey MR, Matous JA, Kwiek JJ, Coltart DM. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2406. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.02.074.

- 13.Zhang Q, Mitasev B, Qi J, Porco JA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14212. doi: 10.1021/ja105784s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imamoto T, Takiyama N, Nakamura K, Hatajima T, Kamiya Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:4392. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Tsuji J, Mandai T. Synthesis. 1996:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Forsyth DA, Estes MR, Lucas P. J Org Chem. 1982;47:4380. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hughes G, Lautens M, Wen C. Org Lett. 2000;2:107. doi: 10.1021/ol991170n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee AK, Sanders DP, Grubbs RH. Org Lett. 2002;4:1939. doi: 10.1021/ol0259793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Please see the Supporting Information for complete experimental details.

- 18.Nicolaou KC, Carenzi GEA, Jeso V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3895. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For enol pivalates of 1,3-cyclohexanediones, see: Boeckman RK, Jr, Sum FW. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4604.Kusama H, Hara R, Kawahara S, Nishimori T, Kashima H, Nakamura N, Morihira K, Kuwajima I. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3811.

- 20.Trace amounts of TFA were required for preparative HPLC purification of synthetic (2) in order to match spectral data for natural (2) provided by the Jacobs group.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.