Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the clinical presentation, manifestations, and response to therapy of portopulmonary hypertension (PPHTN) in pediatric patients.

Study design

This study was a retrospective chart review describing the evaluation and course of 7 patients with PPHTN.

Results

Causes of portal hypertension (HTN) included biliary atresia (3 cases), cavernous transformation of the portal vein (2 cases), and primary sclerosing cholangitis and cryptogenic cirrhosis (1 case each). The median interval from the diagnosis of portal HTN to PPHTN was 12.1 years. Four patients presented with a new heart murmur, 4 presented with syncope, and 3 presented with dyspnea. Although electrocardiograms (ECGs) and chest x-rays were normal in 3 and 2 patients, respectively, echocardiograms diagnosed pulmonary HTN in all 7 patients. Five patients had cardiac catheterizations; the average mean pulmonary artery pressure was 65 ± 20 mm Hg. Response to therapy was variable, and 4 patients died. Postmortem lung tissue examination revealed plexiform lesions and pulmonary arteriopathy.

Conclusions

Because symptoms are subtle and may be overlooked, pediatric patients with portal HTN who develop a new heart murmur, dyspnea, syncope, or who are being evaluated for liver transplantation require evaluation for PPHTN. ECG and chest x-ray are insensitive screens for PPHTN. An echocardiogram and cardiology evaluation is essential for the diagnosis.

Portopulmonary hypertension (PPHTN) is one of the pulmonary vascular disorders complicating chronic liver disease.1 In 1998 the World Health Organization P(WHO) classified PPHTN as pulmonary arterial hypertension (HTN) associated with liver disease or portal HTN.2 PPHTN is defined by elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) (> 25 mm Hg at rest), increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) (>3 Wood units · 3 m2), and normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (<15 mm Hg) in the presence of portal HTN.3 Both hepatic and extrahepatic causes of portal HTN may lead to PPHTN. The prevalence of PPHTN in adult patients with cirrhosis is 0.25% to 0.73% based on autopsy series1,4 and 3.5% to 8.5% in liver transplant candidates.1,5 The diagnosis of PPHTN is usually made 4 to 7 years after the diagnosis of portal HTN in adults.1,6

There are only limited numbers of case reports of children with PPHTN. Pediatric patients with biliary atresia, portal vein thrombosis, focal nodular hyperplasia, and congenital hepatic fibrosis have been reported with pulmonary arterial HTN.7-15 To more fully characterize the clinical presentation, cardiopulmonary abnormalities, and clinical course, we report our experience with 7 children who developed PPHTN.

METHODS

A retrospective review of patient records in the Pediatric Liver Center, Children’s Hospital identified 7 pediatric patients with PPHTN diagnosed between 1995 and 2004 (Table I). All of these children had been previously enrolled in an institutional review board–approved protocol for prospective longitudinal evaluation of childhood pulmonary HTN, for which written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians. Data obtained from the medical record included age at diagnosis of portal HTN and PPHTN, cause of portal HTN, symptoms and/or signs precipitating the evaluation for pulmonary HTN, and additional review of chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), Doppler echocardiogram, right heart catheterization results, lung and liver histology (if available), response to treatment, and overall outcome for each patient. Review of patient records was approved by the institutional review board and was exempted from written consent.

Table 1.

Clinical information on patients with PPHTN

| Patient | Age | Age at portal HTN | Age at PPHTN | Liver disease | Associated diseases | Liver biopsy findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 yrs | 3.5 yrs | 18.2 yrs | CTPV | None | ND |

| 2 | 13.8 yrs* | 10.11 yrs | 13.8 yrs | BA | None | Portal fibrosis |

| 3 | 20.4 yrs* | 2 yrs | 20.4 yrs | CC | CP, scoliosis, prematurity | Portal fibrosis |

| 4 | 13 yrs* | 10 mths | 11.9 yrs | CTPV | Juvenile polyposis | Steatohepatitis |

| 5 | 11 yrs | 8.11 yrs | 3 mths | PSC | ASD | Portal fibrosis |

| 6 | 18 yrs | 8 mths | 17.3 yrs | BA | None | ND |

| 7 | 7 mths* | 4 mths | 7 mths | BA | Complex CHD | Portal fibrosis |

BA, biliary atresia; CC, cryptogenic cirrhosis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; CHD, congential heart disease; CP, cerebral palsy; ASD, atrial septal defect; ND, not done; CTPV, cavernous transformation of the portal vein.

Age at death.

Case Summaries

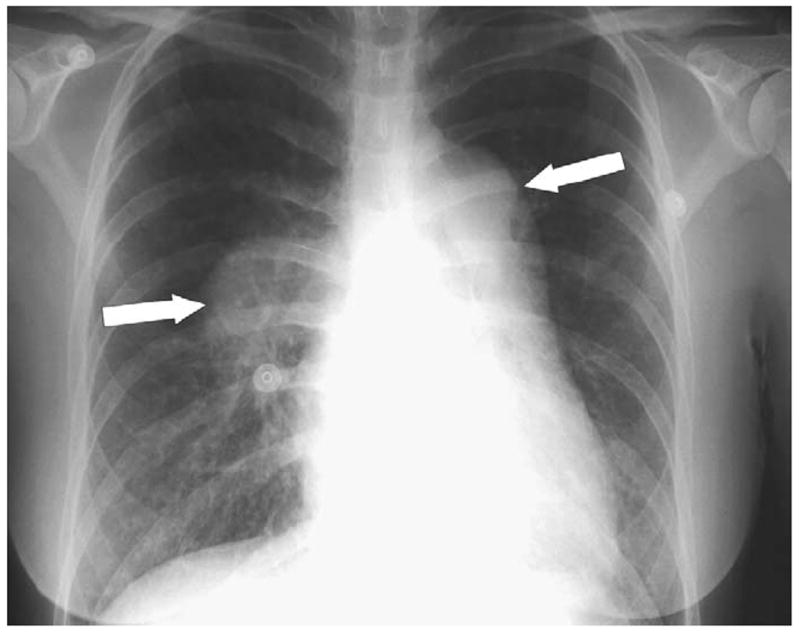

Patient 1, a Caucasian female, presented with splenomegaly and esophageal hemorrhage at age 3.5 years. Portal venogram demonstrated cavernous transformation of the portal vein. The patient underwent partial splenic embolization at age 7 years due to esophageal variceal bleeding refractory to sclerotherapy. At age 16 she developed syncope, which over the next 2 years progressed to shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and orthopnea. Cardiac evaluation included an abnormal chest x-ray (Figure 1), ECG, echocardiogram, and a ventilation-perfusion scan that was negative for a pulmonary embolus (PE) (Table II). Severe pulmonary HTN was documented by cardiac catheterization (Table III). Because the patient initially refused continuous intravenous epoprostenol therapy, nifedipine was initiated. Due to clinical deterioration, epoprostenol treatment was started at age 22 years, and home-inhaled nitric oxide was added at age 24 years.16 At age 26, she developed thyroiditis and was started on tapazol. Progressive pulmonary arterial HTN right-sided heart failure, and syncope were associated with a right ventricular systolic pressure of 156 mm Hg on echocardiography. A graded balloon atrial septostomy was performed without recurrence of syncope. The patient has been found to be an unacceptable candidate for a heart-lung-liver transplant at multiple centers. She is now 27 years old and remains homebound with a WHO functional classification of IV.

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray of patient 1, with arrows indicating dilated pulmonary arteries.

Table II.

Evaluation of patients with PPHTN

| Patient | Chest X-ray | ECG | Echocardiogram | Echocardiogram-RVSP | VQ scan | Hypercoagulability workup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prominent PA | RVH | RVH | 95.8 mm Hg | Normal | Low free/total protein S |

| 2 | Prominent PA | Normal | RVH | 105 mm Hg | Not done | Not done |

| 3 | Normal | Normal | RVH | 45 mm Hg | Not done | Normal |

| 4 | Prominent PA | RVH | RVH | 51.4 mm Hg | Normal | Normal |

| 5 | Normal | RVH | RVH | 85.7 mm Hg | Not done | Normal |

| 6 | Prominent PA | Normal | Normal | 52.8 mm Hg | Normal | Normal |

| 7 | Cardiomegaly | RVH | RVH | 41.5 mm Hg | Normal | Not done |

PA, pulmonary artery; RVH, right ventricular hypertrophy; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure (estimate of tricuspid regurgitation + assumed right atrial pressure); ECG, electrocardiogram; VQ, ventilation perfusion.

Hypercoagulability workup included lupus inhibitor, factor V Leiden, AT III, protein C/S, and cardiolipin IgG/IgM.

Table III.

Cardiac catheterization data

| Patient | Age (years) | Status | PAP (mm Hg) (Normal, <25) | AOP (mm Hg) (Normal, 67-105) | CI (L·min·m2) (Normal, 2.5-3.5) | PVRI (U·m2) (Normal, <2) | PVR/SVR (Normal, <0.1) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.2 | Room air | 85 | 104 | 3.0 | 28.2 | 0.81 | |

| NO+O2 | 62 | 95 | 2.9 | 26.8 | 0.8 | |||

| 18.8 | Room air | 65 | 93 | 3.0 | 18.6 | 0.62 | ||

| NO+O2 | 55 | 93 | 2.6 | 17 | 0.5 | |||

| 23 | O2 | 73 | 75 | 4.9 | 12.65 | 0.91 | EPO | |

| NO+O2 | 64 | 82 | 4.4 | 12.01 | 0.72 | |||

| 26 | O2 | 55 | 55 | 6.6 | 10 | 1 | EPO/atrial septostomy | |

| 4 | 11 | Room air | 72 | 82 | 3.0 | 19.68 | 0.76 | |

| NO+O2 | 62 | 83 | 2.8 | 17.33 | 0.62 | |||

| 13 | Room air | 52 | 65 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 0.7 | EPO | |

| NO+O2 | 54 | 75 | 4.7 | 8.9 | 0.64 | |||

| 5 | 0.3 | Pre-ASD | 50 | 72 | See text | 1.48 | 0.32 | |

| 4 | Post-ASD | 44 | 57 | 3.3 | 10.2 | 0.77 | ||

| 8 | Room air | 64 | 78 | 4.9 | 12.78 | 0.79 | ||

| NO+O2 | 62 | 77 | 4.4 | 10.3 | 0.79 | |||

| 10 | Room air | 57 | 62 | 6.3 | 10.9 | 0.89 | * | |

| NO+O2 | 54 | 60 | 5.5 | 8.4 | 0.87 | |||

| 6 | 17 | Room air | 53 | 100 | 3.8 | 12.29 | 0.47 | |

| NO+O2 | 40 | 101 | 3.5 | 9.56 | 0.34 | |||

| 7 | 0.6 | O2 | 65 | 66 | 8.4 | 4.1 | 0.87 | |

| NO+O2 | 57 | 87 | 7.8 | 1.94 | 0.48 |

AOP, mean arterial pressure; CI, cardiac index; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; U, Wood units; EPO, epoprostenol; ASD, atrial septal defect; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure.

Started on EPO after cardiac catheterization.

Patient 2 underwent a Kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia at age 59 days. At age 10 years, after an exercise-induced syncopal episode, she was found to be anemic with splenomegaly. An upper intestinal endoscopy revealed esophageal varices, which were treated with endoscopic sclerotherapy. Despite attempted variceal ablation and prophylactic propranolol, she continued to have episodic variceal bleeding. At age 13 years she was admitted to the intensive care unit with hematemesis, treated with an octreotide infusion, and found to have portal hypertensive gastropathy without actively bleeding esophageal varices. A soft systolic ejection murmur was noted. Cardiac evaluation included an abnormal chest x-ray and echocardiogram and a normal ECG (Table II). She acutely became hypotensive and suffered a fatal cardio-respiratory arrest. Postmortem examination demonstrated pulmonary arteriopathy with plexiform lesions.

Patient 3, a Caucasian female with cerebral palsy secondary to prematurity, developed jaundice and rectal bleeding at age 2 years. A percutaneous liver biopsy revealed cryptogenic cirrhosis. At age 14 she developed hematemesis and was found to have splenomegaly and a gastric ulcer without esophageal varices. At age 16 a severe gastric variceal hemorrhage prompted placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt complicated by polymicrobial sepsis and ascites. As part of her initial evaluation for liver transplantation, she had a normal chest x-ray and ECG. At age 17 an accentuated pulmonic component of the second heart sound was auscultated. Cardiac evaluation revealed an abnormal echocardiogram suggesting mild pulmonary HTN (Table II). End-stage liver disease developed with hyperammonemia and grade 1-2 encephalopathy, and the patient underwent liver transplantation. During induction for liver transplantation, she suffered a fatal cardiac arrest. Postmortem examination showed plexiform pulmonary arteriopathy with multiple acute pulmonary arterial thrombi.

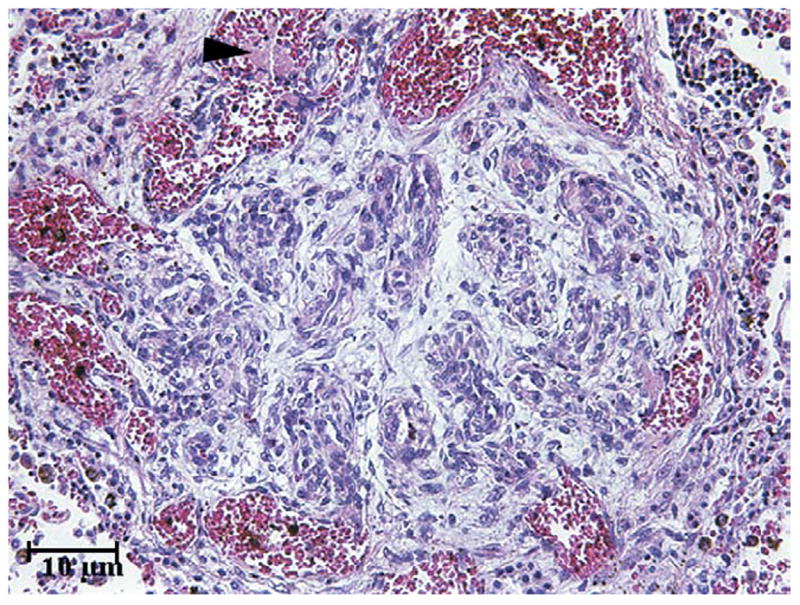

Patient 4, an African-American female, developed abdominal distension, ascites, and anemia at age 10 months. Esophageal varices were found on endoscopy, and angiography identified cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV). Her father had CTPV and juvenile polyposis coli. At age 4 a colonoscopy and upper intestinal endoscopy showed duodenal and colonic juvenile polyps. Evaluation for a hypercoagulable state was negative. At age 11 she was hospitalized for fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and ascites and was found to have nocturnal hypoxia and new heart murmur. Chest x-ray, ECG, and echocardiogram were abnormal. A ventilation-perfusion scan was negative for PE (Table II). Severe pulmonary HTN was demonstrated by cardiac catheterization, with a hepatic vein wedge pressure of 8 mm Hg (Table III). Her family refused epoprostenol therapy. A trial of diltiazem was continued for 4 months, until symptoms progressed and she experienced multiple syncopal episodes. Continuous intravenous epoprostenol therapy was initiated, but she developed fatigue, ascites, and abdominal discomfort associated with a gallop and peripheral edema, prompting albumin and furosemide infusions. Repeat cardiac catheterization showed worsening pulmonary HTN (Table III). At age 13 years she developed lower and then upper extremity paralysis secondary to spinal cord ischemia and hemorrhage. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage ensued, and the patient expired. Postmortem examination showed plexiform pulmonary arteriopathy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lung histology of patient 4, showing an advanced plexiform lesion. The plexiform lesion consists of a glomeruloid plexus of slit-like vessels. This lesion is older and shows organization and multifocal recanalization of the thrombus. A newer, acute, unorganized thrombus is focally present within an adjacent dilated vessel (arrowhead).

Patient 5, a Caucasian male, was born with an atrial septal defect that was surgically closed at age 3 months. His PAP was elevated before surgical repair, with a pulmonary to systemic flow ratio of 2:1 on room air and 3.3:1 on oxygen. The pulmonary to systemic resistance ratio was 0.32:1 on room air and 0.20:1 on oxygen. At age 4, cardiac catheterization demonstrated persistent pulmonary HTN that was nonreactive to hyperventilation and 100% oxygen. He developed exercise intolerance with occasional dyspnea at age 8 years, and a repeat cardiac catheterization demonstrated worsening pulmonary HTN (Table III). He was enrolled in a trial of an endothelin receptor antagonist, bosentan, at age 8.5 years.17 Before initiating bosentan, liver tests were within twice-normal values, increased 2- to 3-fold during the 5 days of therapy, and peaked at 1 month (aspartate aminotransferase, 94; alanine aminotransferase, 325; γ-glutamyltransferase, 656). Liver tests normalized by 2 months after discontinuation of therapy, and an abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal liver with mild splenomegaly. Evaluation for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic liver disease was negative. Liver biopsy revealed severe portal inflammation, early bridging fibrosis, and bile ductular proliferation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed no evidence of large duct strictures or obstruction. Hematochezia developed, and ulcerative colitis was found at colonoscopy. The patient was diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis and was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid, sulfasalazine, and prednisone. Despite aggressive therapy for primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis, pulmonary HTN worsened (Table III). Continuous intravenous epoprostenol therapy was initiated at age 11, and the patient is able to attend school with a WHO classification of III.

Patient 6, a Caucasian female, underwent a gallbladder Kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia at age 96 days with revisions to a Roux-en-Y jejunocystoenterostomy due to poor biliary drainage. At age 16 years she experienced 3 syncopal events and was found to have a prominent pulmonic component of the second heart sound. ECG and echocardiogram were normal. At age 17, due to continued self-limited physical activity, a chest x-ray identified a prominent main pulmonary artery. A ventilation-perfusion scan was negative for PE. A repeat echocardiogram was abnormal (Table II). Cardiac catheterization demonstrated pulmonary arterial HTN with a hepatic vein wedge pressure of 15 mm Hg (Table III). Despite treatment with nifedipine and furosemide, the patient developed a gallop and persistent peripheral edema. Continuous epoprostenol infusion was recommended. She is currently 18 years old and under consideration for liver transplantation with a WHO classification of III.

Patient 7 was diagnosed in utero with complex congenital heart disease. A postpartum echocardiogram showed abnormal systemic venous return with interrupted inferior vena cava and azygous continuation, atrial septal defect, right heart dilatation, a left aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian artery, and bilateral superior vena cava. She was subsequently diagnosed with biliary atresia and underwent a Kasai portoenterostomy at age 71 days. At age 4 months she was hospitalized with respiratory syncitial viral bronchiolitits and had a central venous line placed for nutritional support. At age 7 months she developed sudden respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Cardiac catheterization revealed systemic-level PAPs that were not reactive to oxygen, nitric oxide, or prostacyclin (Table III). Due to refractory persistent pulmonary HTN, severe lung disease, and her cardiac anomalies, she was found to be an unacceptable candidate for liver transplantation. Supportive care was withdrawn, and she expired.

RESULTS

Our patient group comprised 6 females and 1 male with a median age at diagnosis of portal HTN of 24 months (range, 4 to 131 months) and a median age for the diagnosis of pulmonary HTN of 164 months (range, 3 to 244 months). One of the 7 patients was diagnosed with pulmonary HTN before diagnosis of portal HTN. In the remaining 6 patients, the median interval between the diagnosis of portal HTN to PPHTN was 154 months (range, 3 to 220 months) (Table I).

Syncope was present in 4 patients, occurring before the diagnosis of PPHTN in 3 and after the diagnosis of PPHTN in 1. A new heart murmur or prominent pulmonic component of the second heart sound prompted cardiac evaluation in 4 patients. Shortness of breath was found in 2 patients, and dyspnea on exertion was reported in 3 patients.

Chest x-rays were abnormal in 5 of the 7 patients, with either a prominent pulmonary artery or cardiomegaly. Two patients had completely normal chest x-rays. Three patients had normal ECGs, whereas right ventricular hypertrophy was present in 4 patients. Echocardiograms revealed pulmonary HTN in all 7 patients, with a mean baseline right ventricular systolic pressure of 67.4 mm Hg (range, 41.5 to 105 mmHg) (Table II). Five patients underwent cardiac catheterizations which demonstrated a markedly elevated mean PAP of 65 mm Hg (range, 50 to 85 mm Hg), of whom only 1 patient demonstrated vasoreactivity to nitric oxide, suggesting that most of these patients were poor candidates for calcium-channel blocker therapy (Table III).

Three patients were initially treated with calcium channel blockers that did not improve pulmonary hemodynamics, and were subsequently placed on epoprostenol infusions. One patient was initially treated with bosentan, because liver disease was unknown, but then was converted to epoprostenol because of significantly elevated liver function tests.

Of the 3 surviving patients, 1 is homebound and 2 are able to attend school; 1 is married. Four patients died of progressive PPHTN despite aggressive medical management. Two of the 4 patients were considered to have PPHTN that was too severe to allow for safe liver transplantation. Thus, PPHTN showed variable degrees of response to medical management depending on the severity at diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

PPHTN is a serious complication of portal HTN that, when left untreated, is fatal. Once diagnosed, mean survival in adults is 15 months, with a median survival of 6 months.5 Disease progression can be rapid, ranging from 3 weeks to 5 years.18,19 Patients are classified as mild, moderate, or severe depending on the elevation of the mean PAP and PVR, which provides both prognostic and therapeutic considerations.18,19 Clinical symptoms are nonspecific and often subtle. This disorder requires a high index of suspicion for diagnosis. The ultimate treatment is reversal of portal HTN, which may require liver transplantation. However, patients with severe PPHTN have a high mortality with liver transplantation18,19 unless PAP can be lowered into a safe range. Placement of a Swan-Ganz catheter is recommended in patients with PPHTN undergoing liver transplantation.

Our 7 patients are representative of the liver conditions associated with pulmonary arterial HTN in pediatric patients. Unfortunately, when the diagnosis of PPHTN was made based on clinical symptoms, the pulmonary arterial HTN was severe in all cases. We found that our patients’ initial clinical presentation was often subtle. Therefore, our patients had moderate to severe pulmonary HTN at the time of diagnosis of PPHTN resistant to many first-line medications, making them poor candidates for liver transplantation.

In our series, only 3 patients had symptoms of syncope or dyspnea that were recognized before diagnosis of PPHTN. Syncope was the only symptom clearly linked to this condition, occurring in 3 patients prediagnosis and in 1 patient post-diagnosis. A new heart murmur or accentuated P2 by auscultation were physical findings that prompted evaluation. Even despite our high index of suspicion in 2 of the patients, chest x-ray and ECG were normal, which led to deferment of further evaluation for PPHTN. These cases clearly show that an echocardiogram must be performed before excluding the diagnosis of PPHTN. It should be pointed out, however, that even echocardiograms may not detect mild degrees of PPHTN and may underestimate the degree of pulmonary arterial HTN.20,21 Thus, cardiac catheterization is necessary for the diagnosis and further treatment of most patients with PPHTN.

The goal of treatment of PPHTN is to transform a borderline candidate for liver transplantation into an acceptable one, through aggressive treatment of the pulmonary arterial HTN. A thorough evaluation of causes of pulmonary arterial HTN is crucial to the diagnosis and management of this entity. Treatment may include providing supplemental oxygen to maintain saturation above 92%, diuretics to control volume overload, and calcium-channel blockers if the patient has demonstrated good reactivity to vasodilators during cardiac catheterization.3,22-24 Similar to adults, few patients with PPHTN in our series responded to calcium channel blocker therapy. Continuous prostacyclin improves survival in adults and children with idiopathic pulmonary HTN. Unfortunately, prostacylin currently must be given by continuous intravenous infusion, necessitating central venous catheterization with its associated complications.

If the diagnosis of PPHTN is made early before the development of irreversible pulmonary vasculopathy, then liver transplantation can be successfully performed and may reverse the process of PPHTN.25 The mesenterico-left portal bypass has been proposed to restore intrahepatic portal flow and reduce portal HTN in children with CTPV. In children with CTPV and normal liver histology and anatomy, this procedure has been effective in reversing portal HTN and its sequelae,26 although this procedure has not been reported in children with significant PPHTN.

PPHTN, by definition, involves deleterious effects of portal HTN on pulmonary vasculature.27 Portal HTN causes increased cardiac output that may induce sheer stress from increased pulmonary blood flow, resulting in endothelial damage. It has also been postulated that portal HTN causes release of humoral mediators, cytokines, and endotoxins, which may stimulate increased flow and sheer stress in the pulmonary circulation. The net result is an increased vascular resistance caused by vasoconstriction, which can lead to pulmonary vascular remodeling and proliferation of pulmonary arterial endothelial cells, resulting in pulmonary HTN.

A previous study has shown that patients with end-stage liver disease and PPHTN undergoing liver transplantation have high mortality compared with transplant patients without PPHTN.28 The current Mayo Clinic intraoperative guidelines in patients with PPHTN recommend pursuing liver transplantation in patients with a mean PAP < 35 mm Hg or in patients with a mean PAP between 35 and 50 mm Hg with a PVR of < 3 Wood units · 3 m2.28 One study reported a 100% mortality rate in adult patients with a mean PAP of > 50 mm Hg who underwent liver transplantation and a 50% mortality rate in adult patients with mean PAP between 35 and 50 mm Hg with a PVR > 3 Wood units · 3 mm2.28 Unfortunately, up to 60% of patients with PPHTN do not have the condition detected before induction of anesthesia for liver transplantation.3,21

Our geographic referral base represents a population living at moderate elevation (1600 meters above sea level in Denver). This relative hypoxia may complicate an already diseased pulmonary vasculature, accelerating the appearance of symptoms. However, hypoxia is not a required stimulus for the development of PPHTN in children, because PPHTN has been described at sea level,29 and 1 of our 7 patients developed PPHTN while living at sea level.

Currently there is no accepted universal screening protocol for PPHTN in patients with portal HTN or in those undergoing evaluation for liver transplantation. This raises the question of how pediatric patients should be screened. Is it justifiable to screen all pediatric patients with chronic liver disease or wait until they are candidates for liver transplantation? We believe that delayed diagnosis predisposes to more severe disease and potentially may preclude liver transplantation. We agree that echocardiography should be the recommended screening test for PPHTN because of the lack of sensitivity of chest x-ray and ECG.30,31 We also agree with the European Respiratory Task Force’s recommendations to screen all patients before liver transplantation with transthoracic echocardiography to detect PPHTN before induction.3 We propose the development of a national database for PPHTN in pediatric patients that could define the natural history and response to therapy of this entity, facilitate multicenter trials, and ultimately lead to evidence-based recommendations for screening and treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant M01-RR00069 from the General Clinical Research Center branch of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- CTPV

Cavernous transformation of the portal vein

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- HTN

Hypertension

- PAP

Pulmonary arterial pressure

- PPHTN

Portopulmonary hypertension

- PVR

Pulmonary vascular resistance

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2nd World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, July 5, 2004, Paris, France.

D. Dunbar Ivy receives funding for clinical trials from Actelion and Pfizer, manufacturers of medications used to treat pulmonary hypertension.

References

- 1.Budhiraja R, Hassoun PM. Portopulmonary hypertension: a tale of two circulations. Chest. 2003;123:562–76. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich S. Primary pulmonary hypertension: executive summary from the world symposium on primary pulmonary hypertension 1998. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriquez-Roisin R, Krowka MJ, Herve PH, Fallon MB. ERS Task Force: pulmonary-hepatic vascular disorders. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:861–80. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00010904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonnel PJ, Toye PA, Hutchins GM. Primary pulmonary hypertension and cirrhosis: are they related? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:437–41. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsay MA, Simpson BR, Nguyen AT, Ramsay KJ, East C, Klintmalm GB. Severe pulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:494–500. doi: 10.1002/lt.500030503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadengue A, Benhayoun MK, Lebrec D, Benhamou JP. Pulmonary hypertension complicating portal hypertension: prevalence and relation to splanchnic hemodynamics. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:520–8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90225-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soh H, Hasegawa T, Sasaki T, Azuma T, Okada A, Mushiake S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension associated with postoperative biliary atresia: report of two cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1779–81. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boot H, Visser FC, Thijs JC, Meuwissen SGM. Pulmonary hypertension complicating portal hypertension: a case report with suggestions for a different therapeutic approach. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:656–60. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu CM, Chiu CT, Lien JM, Ng KF. Severe portopulmonary hypertension in congenital hepatic fibrosis. Chang Gung Med J. 2003;26:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flemale A, Sabot JP, Popijn M, Procureur M, Urbain G, Dierckx JP, et al. Pulmonary hypertension associated with portal thrombosis. Eur J Respir Dis. 1985;66:224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver MM, Bohn D, Shawn DH, Shukett B, Eich G, Rabinovitch M. Association of pulmonary hypertension with congenital portal hypertension in a child. J Pediatr. 1992;120:321–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MD, Rubin LJ, Taylor WE, Cuthbert JA. Primary pulmonary hypertension: an unusual case associated with extrahepatic portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1983;3:588–92. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portmann B, Stewart S, Higenbottam TW, Clayton PT, Lloyd JK, Williams R. Nodular transformation of the liver associated with portal and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:616–21. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90435-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg LS, Silverman A, Strain JE. Primary pulmonary hypertension presenting as portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;71:427–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chongsrisawat V, Vivatvakin B, Suwangool P, Vajragupta L, Poovorawan Y. Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis associated with pulmonary arteriovenous communication and pulmonary arterial hypertension. SE Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:76–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivy DD, Parker D, Doran A, Kinsella JP, Abman S. Acute hemodynamic effects and home therapy using a novel pulsed nasal nitric oxide delivery system in children and young adults with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:886–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barst RJ, Ivy D, Dingemanse J, Widlitz A, Schmitt K, Doran A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of bosentan in pediatric patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:372–82. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9236(03)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsay MA. Liver transplant considerations and outcomes for the portopulmonary hypertension patient. Adv Pulmon Hypertens. 2004;3:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsay MA. Perioperative mortality in patients with portopulmonary hypertension undergoing liver transplantation [editorial] Liver Transpl. 2000;6:451–2. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.8859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivy DD. Echocardiographic evaluation of pulmonary hypertension. In: Valdes-Cruz LM, Cayre RO, editors. Echocardiographic diagnosis of congenital heart disease: an embryologic and anatomic approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 537–47. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim WR, Krowka MJ, Plevak DJ, Lee J, Rettke SR, Frantz RP, et al. Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the assessment of pulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:453–8. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galie N, Seeger W, Naeije R, Simonneau G, Rubin LJ. Comparative analysis of clinical trials and evidence-based treatment algorithm in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:81S–8S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenzweig EB, Widlitz AC, Barst RJ. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38:2–22. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashid A, Ivy D. Severe paediatric pulmonary hypertension: new management strategies. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:92–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.048744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Losay J, Piot D, Bourgaran J, Ozier Y, Devictor D, Houssin D, et al. Early liver transplantation is crucial in children with liver disease and pulmonary artery hypertension. J Hepatol. 1998;28:337–42. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(88)80022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bambini DA, Superina R, Almond PS, Whitington P, Alonso E. Experience with the Rex shunt (mesenterico-left portal bypass) in children with extrahepatic portal hypertension. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:13–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(00)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoeper MM, Krowka MJ, Strassburg CP. Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome. Lancet. 2004;363:1461–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krowka M, Plevak DJ, Findlay, Rosen CB, Wiesner RH, Krom RA. Pulmonary hemodynamics and perioperative cardiopulmonary-related mortality in patients with portopulmonary hypertension undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:443–50. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.6356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato H, Katori T, Nakamura Y, Kawarasaki H. Moderate-term effect of epoprostenol on severe portopulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:50–3. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotton C, Gandhi S, Vaitkus P, Massad MG, Benedetti E, Mrtek RG, et al. Role of echocardiography in detecting portopulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:1051–4. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.35554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colle I, Moreau R, Godinho E, Belghiti J, Ettori F, Cohen-Solal A, et al. Diagnosis of portopulmonary hypertension in candidates for liver transplantation: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2003;37:401–9. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]