Abstract

Objective

To identify possible prepregnancy risk factors for antepartum stillbirth and determine if these factors identify women at higher risk for term stillbirth.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study of prepregnancy risk factors compared 712 singleton antepartum stillbirths to 174,097 singleton live births at or after 23 weeks of gestation. The risk of term antepartum stillbirth was then assessed in a subset of 155,629 singleton pregnancies.

Results

In adjusted multivariable analyses, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, maternal age 35 years or older, nulliparity, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) 30 kg/m2 or higher, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, smoking, and alcohol use were independently associated with stillbirth. Prior cesarean delivery and history of preterm birth were associated with increased stillbirth risk in multiparas. The risk of a term stillbirth for women who were white, 25–29 years old, normal weight, multiparous, no chronic hypertension, and no preexisting diabetes was 0.8 per 1,000. Term stillbirth risk increased with these conditions: preexisting diabetes (3.1 per 1,000), chronic hypertension (1.7 per 1,000), black race (1.8 per 1,000), maternal age 35 years or older (1.3 per 1,000), BMI 30 kg/m2 or higher, (1/1000) and nulliparity (0.9 per 1,000).

Conclusion

There are multiple independent risk factors for antepartum stillbirth. However, the value of individual risk factors of race, parity, advanced maternal age (35– 39 years old) and BMI to predict term stillbirth is poor. Our results do not support routine antenatal surveillance for any of these risk factors when present in isolation.

Introduction

Stillbirth, defined as fetal deaths of 20 weeks of gestation or more, is one of the most common adverse pregnancy outcomes in the United States and occurs in 1 out of every 200 pregnancies. The number of stillbirths per year (25,894) is about equivalent to the number of infant deaths (28,384) (2005 data). (1) The Healthy People 2010 target goal for the U.S. stillbirth rate is 4.1 fetal deaths per 1,000 births; the current rate at 6.2 per 1,000 births is 52% higher than this goal. (2005 data) (1)

Factors that have been associated with an increased risk of antepartum stillbirth include previous adverse pregnancy outcomes (2), advanced maternal age (3), black race (4), smoking (5), maternal medical disease such as pregestational diabetes and chronic hypertension (6), fetal growth impairment (7) and assisted reproductive technology. (8) The most prevalent independent risk factors are nulliparity (5), obesity (9) and advanced maternal age. Women who are obese and those of advanced maternal age constitute an increasingly large proportion of the obstetric population and may be contributing to the lack of decrease in the rate of stillbirth in the U.S. over the past decade.

Particularly devastating is the occurrence of a term stillbirth, a proportion of which have no clinical explanation or certain cause despite a complete evaluation. Huang et al. in their hospital-based cohort study of 84,294 births weighing 500 g or more from 1961–1974 and 1978–1996 found that two thirds of all unexplained fetal deaths occurred after 35 weeks of gestation. (10) Experts have postulated that this outcome may be avoided by increased antenatal surveillance and intervening for risk factors such as advanced maternal age, although the evidence for this practice is limited (11).

The purpose of this study was to identify possible risk factors for antepartum stillbirth and estimate their relative contribution stratified by parity in a large cohort of antepartum stillbirths with detailed medical record information controlling for a variety risk factors. In addition, this study attempted to determine if potential demographic and prepregnancy factors can be used to identify women at a significantly higher risk for stillbirth at term compared to the general population.

Materials and Methods

The Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL) was a study conducted by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health and has been described in detail elsewhere. (12) In brief, this was a retrospective cohort study involving 228,668 deliveries between 2002 and 2008 from 12 clinical centers and 19 hospitals representing nine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (the College) districts. All deliveries at 23 weeks of gestation or greater were included in the CSL cohort. Women could have more than one pregnancy in the cohort; so to avoid intra-person correlation we only included the first pregnancy enrolled for a total of 206,969 women. Two institutions that had a large percentage of components of the maternal medical history missing were excluded from these analyses. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained by all participating institutions.

Demographic data, medical history, prenatal, labor and delivery information as well as postpartum and neonatal outcomes were extracted from electronic medical records from each institution. Data from the neonatal intensive care unit was collected and linked to the newborn record. Maternal and newborn discharge ICD-9 codes were also collected for each delivery. Data was transferred in electronic format from each site and was mapped to common categories for each pre-defined variable at the data coordinating center. Data inquiries, cleaning and logic checking were performed. Validation studies were performed for four key variables and the electronic medical records were found to be a reasonably accurate representation of the medical charts. (12)

All singleton deliveries ≥ 23 weeks of gestation from 10 institutions that have comprehensive electronic obstetric and neonatal databases were obtained and comprise the cohort for this analysis. Antepartum stillbirths included in this study were defined as having no signs of life prior to labor with Apgar scores 0/0. Intrapartum stillbirths were defined as fetal death during labor. Live births were defined as having a non – zero Apgar score at birth.

The primary outcome variable studied in the cohort was the occurrence of antepartum stillbirth versus live birth at 23 weeks of gestation and beyond. Information on prepregnancy factors was abstracted from the institutions’ electronic medical records. The following maternal characteristics were included: race (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, Other/multiracial), maternal age (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, ≥40 years), marital status (married, not married/unknown); insurance (private, public, self pay, other/unknown); parity (nulliparas, multiparas); prior cesarean delivery, prior preterm birth, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, smoking prior/during pregnancy, alcohol prior/during pregnancy, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) [Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), Normal weight (18.5– 24.9 kg/m2), Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) and Missing], and HIV status. Because missing information may not occur at random, we treated missing values as a separate category.

Univariable analysis was performed using chi-square test. Multivariable analysis of the gestational age at stillbirth (with gestational age at live birth as a censoring time) used Cox proportional hazard regression to calculate adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals to assess the strength of the relationship between a potential risk factor and the occurrence of antepartum stillbirth. Subsequently, adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated stratified by parity. Our multivariable model was a generalized linear mixed model with site (center) as a random effect using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS.

In order to determine if the prepregnancy risk factors for stillbirth were the same for stillbirths at term, we repeated the analysis in singleton pregnancies that delivered between 37 – 42 weeks of gestation, using only race, maternal age, parity, BMI, preexisting diabetes and chronic hypertension. Due to a small number of women ≥ 40 years old with an antepartum stillbirth in the cohort (n=7), a single category of maternal age ≥ 35 years old was used. To calculate an absolute risk of stillbirth based on various individual and combined risk factors, we first computed a baseline absolute risk in women who served as the reference group in the Cox model (i.e., non-Hispanic white, multiparas, 25–29 years old, normal BMI (18.5– 24.9 kg/m2), non-diabetic and no history of chronic hypertension). Then we used the adjusted hazard ratios from the Cox model to calculate adjusted absolute risks for each individual risk factor. We also used the adjusted beta-coefficients in the Cox model to calculate combined adjusted absolute risks for women who carried multiple risk factors (13). Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) version 9.1.

Results

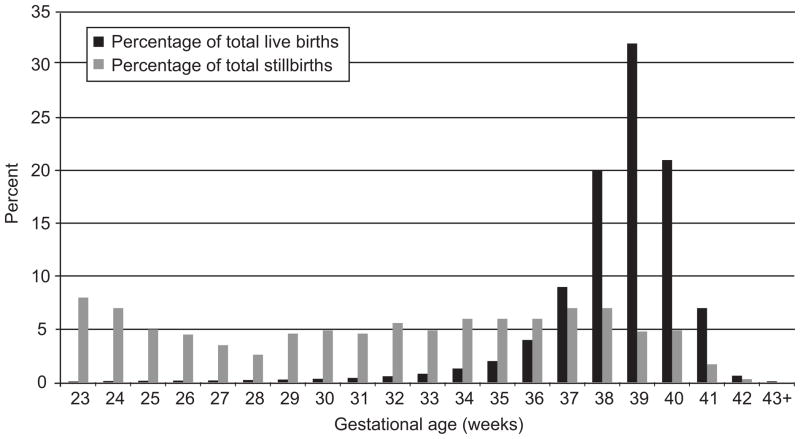

The overall rate of stillbirth was 5.2 per 1000 births at or after 23 weeks of gestation in the CSL cohort. There were a total 183,760 births at 23 weeks of gestation and beyond in this cohort of women delivering in 10 institutions. A total of 8,951 deliveries were excluded which consisted of 8,076 multiple gestations, 109 intrapartum stillbirths, 78 not specified stillbirths, 574 neonatal deaths and 272 women for missing maternal age (there was overlap among multiple gestation births, stillbirths and births with maternal age missing), leaving 174,809 singleton deliveries to be analyzed. A total of 712 singleton antepartum stillbirths were compared to 174,097 singleton live births for prepregnancy risk factors. The average gestational age at delivery for antepartum singleton stillbirths was 31.9 weeks vs. 38.5 weeks for live births. Figure 1 shows the gestational age distribution for singleton antepartum stillbirths and singleton live births in this cohort.

Figure 1.

The distribution of antepartum stillbirths and live births in the cohort by gestational age in weeks.

Race, maternal age, marital status, insurance, parity, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, smoking, alcohol, prepregnancy BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and HIV were all significantly associated with antepartum stillbirth in univariable analyses. (Table 1) When analyses were stratified by parity, race, maternal age, marital status, insurance, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension and prepregnancy BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 were all significantly associated with antepartum stillbirth, regardless of parity. For nulliparas (parity =0), HIV status was significantly associated with antepartum stillbirth. For multiparas (parity ≥ 1), previous preterm birth, smoking and alcohol were significantly associated with antepartum stillbirth. A history of prior cesarean delivery showed a trend with being associated with antepartum stillbirth but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06).

Table 1.

Univariable analyses of pre-pregnancy characteristics comparing antepartum singleton stillbirths to singleton live births stratified by parity.

| Maternal characteristics | Whole population | Nulliparas (parity=0) | Multiparas (parity>=1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singleton live birth N: 174097 |

Antepartum singleton stillbirth N: 712 |

Singleton live birth N: 75939 |

Antepartum singleton stillbirth N: 346 |

Singleton live birth N: 98158 |

Antepartum singleton stillbirth N: 366 |

||||

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | p-value | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | p-value | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | p-value | |

| Race | |||||||||

| White/non-Hispanic | 90778 (52.1) | 239 (33.6) | <0.0001 | 39808 (52.4) | 121 (35.0) | <0.0001 | 50970 (51.9) | 118 (32.2) | <0.0001 |

| Black/non-Hispanic | 33737 (19.4) | 226 (31.7) | 14294 (18.8) | 113 (32.7) | 19443 (19.8) | 113 (30.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 29271 (16.8) | 141 (19.8) | 11789 (15.5) | 62 (17.9) | 17482 (17.8) | 79 (21.6) | |||

| Asian | 7250 (4.2) | 10 (1.4) | 3817 (5.0) | 4 (1.2) | 3433 (3.5) | 6 (1.6) | |||

| Other/Multi-racial/Unknown | 13061 (7.5) | 96 (13.5) | 6231 (8.2) | 46 (13.3) | 6830 (7.0) | 50 (13.7) | |||

| Maternal age (Years old) | |||||||||

| <20 | 15126 (8.7) | 84 (11.8) | <0.0001 | 13040 (17.2) | 75 (21.7) | 0.15 | 2086 (2.1) | 9 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| 20–24 | 42372 (24.3) | 177 (24.9) | 24814 (32.7) | 111 (32.1) | 17558 (17.9) | 66 (18.0) | |||

| 25–29 | 49041 (28.2) | 171 (24.0) | 18544 (24.4) | 83 (24.0) | 30497 (31.1) | 88 (24.0) | |||

| 30–34 | 40136 (23.1) | 135 (19.0) | 12310 (16.2) | 52 (15.0) | 27826 (28.3) | 83 (22.7) | |||

| 35–39 | 21708 (12.5) | 109 (15.3) | 5786 (7.6) | 17 (4.9) | 15922 (16.2) | 92 (25.1) | |||

| >40 | 5714 (3.3) | 36 (5.1) | 1445 (1.9) | 8 (2.3) | 4269 (4.3) | 28 (7.7) | |||

| Marital | |||||||||

| Married | 105553 (60.6) | 332 (46.6) | <0.0001 | 41558 (54.7) | 135 (39.0) | <0.0001 | 63995 (65.2) | 197 (53.8) | <0.0001 |

| Not married/Unknown | 68544 (39.4) | 380 (53.4) | 34381 (45.3) | 211 (61.0) | 34163 (34.8) | 169 (46.2) | |||

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Private | 102225 (58.7) | 321 (45.1) | <0.0001 | 44477 (58.6) | 149 (43.1) | <0.0001 | 57748 (58.8) | 172 (47.0) | <0.0001 |

| Public | 49145 (28.2) | 200 (28.1) | 20378 (26.8) | 104 (30.1) | 28767 (29.3) | 96 (26.2) | |||

| Self pay | 1929 (1.1) | 11 (1.5) | 881 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 1048 (1.1) | 9 (2.5) | |||

| Other/Unknown | 20798 (11.9) | 180 (25.3) | 10203 (13.4) | 91 (26.3) | 10595 (10.8) | 89 (24.3) | |||

| Parity | |||||||||

| Nuliparous | 75939 (43.6) | 346 (48.6) | 0.008 | ||||||

| Multiparous | 98158 (56.4) | 366 (51.4) | |||||||

| Prior CS | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 75960 (77.4) | 268 (73.2) | 0.06 | ||||||

| Yes | 22198 (22.6) | 98 (26.8) | |||||||

| Preterm birth | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 87175 (88.8) | 310 (84.7) | 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 10983 (11.2) | 56 (15.3) | |||||||

| Preexisting diabetes | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 171494 (98.5) | 682 (95.8) | <0.0001 | 74981 (98.7) | 332 (96.0) | <0.0001 | 96513 (98.3) | 350 (95.6) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 2603 (1.5) | 30 (4.2) | 958 (1.3) | 14 (4.0) | 1645 (1.7) | 16 (4.4) | |||

| Chronic hypertension | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 155832 (89.5) | 612 (86.0) | <0.0001 | 68492 (90.2) | 300 (86.7) | <0.0001 | 87340 (89.0) | 312 (85.2) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 4463 (2.6) | 47 (6.6) | 1855 (2.4) | 21 (6.1) | 2608 (2.7) | 26 (7.1) | |||

| Missing | 13802 (7.9) | 53 (7.4) | 5592 (7.4) | 25 (7.2) | 8210 (8.3) | 28 (7.7) | |||

| Smoking prior/during pregnancy | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 163120 (93.7) | 644 (90.4) | 0.0004 | 71922 (94.7) | 320 (92.5) | 0.07 | 91198 (92.9) | 324 (88.5) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 10977 (6.3) | 68 (9.6) | 4017 (5.3) | 26 (7.5) | 6960 (7.1) | 42 (11.5) | |||

| Alcohol prior/during pregnancy | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 170965 (98.2) | 690 (96.9) | 0.01 | 74559 (98.2) | 339 (98.0) | 0.77 | 96406 (98.2) | 351 (95.9) | 0.0009 |

| Yes | 3132 (1.8) | 22 (3.1) | 1380 (1.8) | 7 (2.0) | 1752 (1.8) | 15 (4.1) | |||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| Missing | 55199 (31.7) | 262 (36.8) | 0.0004 | 24107 (31.7) | 137 (39.6) | 0.01 | 31092 (31.7) | 125 (34.2) | 0.01 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 6508 (3.7) | 19 (2.7) | 3494 (4.6) | 12 (3.5) | 3014 (3.1) | 7 (1.9) | |||

| Normal weight (18.5–25) | 64617 (37.1) | 220 (30.9) | 30992 (40.8) | 117 (33.8) | 33625 (34.3) | 103 (28.1) | |||

| Overweight (25–30) | 26489 (15.2) | 103 (14.5) | 10238 (13.5) | 43 (12.4) | 16251 (16.6) | 60 (16.4) | |||

| >=30 | 21284 (12.2) | 108 (15.2) | 7108 (9.4) | 37 (10.7) | 14176 (14.4) | 71 (19.4) | |||

| HIV/AIDS | |||||||||

| No/Unknown | 166315 (95.5) | 676 (94.9) | 0.02 | 72687 (95.7) | 331 (95.7) | 0.02 | 93628 (95.4) | 345 (94.3) | 0.23 |

| Yes | 731 (0.4) | 8 (1.1) | 244 (0.3) | 4 (1.2) | 487 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) | |||

| Missing | 7051 (4.1) | 28 (3.9) | 3008 (4.0) | 11 (3.2) | 4043 (4.1) | 17 (4.6) | |||

Multivariable analyses were performed in the entire cohort (N=174,809) and adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated (Table 2). Black and Hispanic women had a 2.0 (95% CI 1.6, 2.4) and 1.5 fold (95% CI 1.2, 1.9) increased risk of antepartum stillbirth, respectively, when compared to white women. Asian race was associated with half of the antepartum stillbirth risk compared to white women (aHR= 0.5, 95% CI 0.3, 0.9). Maternal ages 35 – 39 years old and 40 and greater were associated with a 1.4 fold (95% CI 1.1, 1.8) and 1.6 fold (95% CI 1.1, 2.3) increased antepartum stillbirth risk compared to women 25–29 years old. Nulliparity was associated with a 1.2 fold (95% CI 1.1, 1.5) increased risk of antepartum stillbirth. Preexisting diabetes (aHR = 2.7, 95% CI 1.8, 3.9), chronic hypertension (aHR= 2.0, 95% CI 1.5, 2.8), smoking (aHR= 1.6, 95% CI 1.2, 2.1) and alcohol use (aHR= 1.7, 95% CI 1.1, 2.6) were all independently associated with antepartum stillbirth when compared to women without these conditions. Pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was associated with a 1.3 fold (95% CI 1.0, 1.7) increased risk of antepartum stillbirth compared to normal weight women (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of pre-pregnancy characteristics comparing antepartum singleton stillbirths to singleton live births stratified by parity.

| Whole population N: 174809 Adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) |

Nulliparas N:76285 Adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) |

Multiparas N: 98524 Adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| White/non-Hispanic | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Black/non-Hispanic | 2.0 (1.6, 2.4) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) | |

| Hispanic | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | |

| Asian | 0.5 (0.3, 0.9) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | |

| Other/Multi-racial/Unknown | 2.4 (1.8, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8) | 2.8 (2.0, 4.0) | |

| Maternal age (Years old) | ||||

| 25–29 | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| <20 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | |

| 20–24 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | |

| 30–34 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | |

| 35–39 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.5) | |

| >40 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.3) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.2) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.0) | |

| Marital | ||||

| Married | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Not married/Unknown | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Public | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | |

| Self pay | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) | 0.5 (0.1, 2.0) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.8) | |

| Other/Unknown | 2.4 (2.0, 3.0) | 2.8 (2.1, 3.7) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.1) | |

| Parity | ||||

| Multiparas | Referent | |||

| Nulliparas | 1.2 (1.1, 1.5) | |||

| Prior CS | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | |||

| Yes | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | |||

| Preterm birth | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | |||

| Yes | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | |||

| Preexisting diabetes | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Yes | 2.7 (1.8, 3.9) | 3.5 (2.0, 6.1) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.5) | |

| Chronic hypertension | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Yes | 2.0 (1.5, 2.8) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.3) | 1.9 (1.3, 3.0) | |

| Missing | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Yes | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | |

| Alcohol during pregnancy | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Yes | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.4) | 2.2 (1.3, 3.8) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal weight (18.5–25) | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Missing | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | |

| Overweight (25–30) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | |

| >=30 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) | |

| HIV/AIDS | ||||

| No/Unknown | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Yes | 1.9 (0.9, 3.8) | 2.5 (0.9, 6.7) | 1.5 (0.6, 4.0) | |

| Missing | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.5) | |

Since multiparas have different risk factors for stillbirth that nulliparas are not at risk for, multivariable analyses were then performed stratified by parity (Table 2). In nulliparas (N=76,285), black race, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension and smoking were associated with antepartum stillbirth when adjusted for the other risk factors. Analyses of the multiparas cohort (N= 98,524) demonstrated 2 additional risk factors associated with an increased antepartum stillbirth risk. The risk of antepartum stillbirth increased 1.3 fold (95% CI 1.0, 1.6) for a history of prior cesarean delivery and 1.6 fold 1.6 (95% CI 1.2, 2.1) for history of preterm birth when adjusted for the other risk factors. There was an increased antepartum stillbirth risk associated with black and Hispanic race, maternal age ≥ 35 years, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, smoking, alcohol and prepregnancy BMI > 30 kg/m2 in multiparas when adjusted for the other risk factors.

In order to determine if the prepregnancy risk factors for stillbirth were the same for stillbirths at term, we repeated the analysis in 155,859 singleton pregnancies that delivered between 37 – 42 weeks of gestation, which was comprised of 155,544 singleton live births and 185 singleton antepartum stillbirths. For women who delivered between 37 – 42 weeks of gestation who were in the referent group for all 6 variables (white non-Hispanic, 25–29 years old, normal weight (BMI 18.5–25 kg/m2), multiparous, no chronic hypertension and no preexisting diabetes) the baseline risk of stillbirth 37–42 weeks of gestation was exceedingly low: 0.8/1,000. The adjusted absolute risk of stillbirth in ongoing pregnancies at 37 weeks of gestation increased as the following factors were individually changed (leaving the other variables in the referent group): Preexisting diabetes (3.1/1000), chronic hypertension (1.7/1000), black race (1.8/1,000), maternal age ≥ 35 years old (1.3/1000), BMI > 30 kg/m2 (1/1000) and nulliparity (0.9/1,000). Women who were black, ≥ 35 years old, nulliparous and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 without diabetes or chronic hypertension had an absolute risk of stillbirth of 4.4/1000 of ongoing pregnancies (a relative risk of 5.5 compared to women with no risk factors (the referent group)).

Discussion

This study represents a large cohort of viable pregnancies (23 weeks of gestation and greater) to study the risk of antepartum stillbirth in the U.S with detailed information from electronic medical records. As in previous studies the following factors were associated with increased risk of antepartum stillbirth: Black race, Hispanic race, nulliparity, advanced maternal age (> 35 years old), prepregnancy BMI > 30 kg/m2, smoking and chronic hypertension, prepregnancy diabetes. (3–6, 9) Because of the large number of women in the cohort, adjusted hazard ratios could be calculated controlling for all these variables which is unique and confirms the individual contribution of each risk factor to antepartum stillbirth.

Smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity were demonstrated to be independent risk factors even when adjusting for other relevant variables such as preexisting diabetes, hypertension, maternal age and race. Because these are modifiable risk factors for stillbirth, preconception care should be directed at smoking and drinking cessation and optimizing pre-pregnancy weight. Women who quit smoking from their first to second pregnancy have been shown to reduce their risk of stillbirth to the same level as nonsmokers in the second pregnancy. (14)

Previous preterm birth was a significant risk factor for stillbirth with a 1.6 fold increase risk of stillbirth. The relationship with previous preterm birth has been reported in other studies.(2) In clinical practice the focus for women with a previous preterm birth has been to prevent recurrent preterm birth. Even controlling for covariates such as pregestational maternal disease and exposures that are associated with preterm birth and stillbirth, a consistent relationship between previous preterm birth and stillbirth is seen in this study. This reinforces the concept that preterm birth in a prior pregnancy is a marker for biological susceptibility to adverse pregnancy outcome beyond recurrent preterm birth.

Previous cesarean delivery was independently associated with a 1.3 fold increased risk of antepartum stillbirth in our study. The relationship between previous cesarean delivery and subsequent antepartum stillbirth has been controversial. A large study of over 100,000 births in Scotland reported a 1.6 fold increased risk of unexplained stillbirth (95% CI 1.2–2.3) in women with a previous cesarean delivery. (15) An analysis of birth certificate data from almost 400,000 births in Missouri demonstrated a 1.4 fold increased risk of stillbirth (95% CI 1.1–1.7) with previous cesarean delivery for black women, but no association among white women. (16) However, an analysis of U.S. birth certificate and fetal death report data between 1995 and 1997 of over 11 million records showed no association between previous caesarean delivery and the risk of stillbirth. (17) Vital statistics data has certain limitations. First, misclassification of history of previous cesarean delivery may occur using birth certificate data with repeat cesarean delivery with labor and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery being known to be significantly underreported. (18) Also, because the U.S. fetal death data is collected on a separate data collection form from live births or infant deaths, the fetal death data has more data quality issues and a higher percent of not stated responses for certain variables such as method of delivery than either live birth or infant death data. (19) Our data confirms a 1.3 fold increase risk of antepartum stillbirth for women with a previous cesarean delivery controlling for important covariates such as maternal disease, race, prior preterm delivery and BMI. As the overall rates of cesarean delivery continue to increase in the U.S., an association between cesarean delivery and subsequent stillbirth risk is concerning.

Despite analyzing a large cohort of pregnancies with detailed electronic medical records there are limitations to the study. A limitation was the inability to analyze the data according to likely cause of death. Unlike live births where congenital anomalies, neonatal morbidities and cause of death are captured in the neonatal charts, the results of perinatal autopsy and the stillbirth workup are not captured in the maternal chart and a separate chart of the stillbirth similar to a neonatal chart was not generated. This fact makes research on stillbirth difficult and requires prospective collection of this information. In addition, despite using medical records conditions such as assisted reproductive technology and previous stillbirth could not be analyzed due to a high percentage of missing data. However, when considering our analyses of term stillbirths, these limitations of the data are less of an issue because the majority are unexplained.(10) They are not associated with PPROM and less likely to be associated with karyotypic abnormalities and congenital anomalies. We were also unable to analyze the use of antepartum testing in the cohort. Presumably women with conditions such as pregestational diabetes and chronic hypertension underwent antepartum testing which may have decreased the stillbirth risk observed with these conditions in this study. Likewise, although there is no ACOG recommendation regarding testing for factors such as advanced maternal age or obesity for example, the performance of antepartum testing may have decreased the stillbirth risk associated with these factors in this cohort. Lastly, although there was wide geographic variation among the participating centers, this cohort may not be representative of the U.S. because some of these hospitals are tertiary care centers; women delivering at these centers may differ in certain characteristics influencing pregnancy outcome.

In a population without preexisting medical disease or other obstetric complications, there is little direct data to assess whether antepartum testing will improve fetal outcomes.

We focused on term stillbirths because the institution of antepartum testing for the presence of risk factors is not without consequence. Antepartum testing is associated with false positive results, which may lead to further unnecessary testing or delivery. In the case of preterm gestations, antepartum testing to prevent stillbirth could lead to iatrogenic preterm delivery which would be undesirable.

Advanced maternal age by itself has been identified as a significant risk factor for stillbirth at term and the benefits and risks of routine antepartum testing on the basis of maternal age alone has been explored.(20) Fretts and colleagues, studied both maternal age and parity as predictors of unexplained fetal death in the McGill Obstetrical Neonatal Database data set. The authors found that nulliparous women aged 35 years and older had a 3.3-fold increase in the risk of unexplained fetal death compared with women younger than 35 years of age. The odds ratio for maternal age 40 years and older was 3.7. Their conclusion was that compared with no testing, a policy of weekly antepartum testing beginning at 37 weeks of gestation in otherwise low-risk women aged 35 years and older, with induction of labor for women with abnormal test results, would result in a reduction in unexplained fetal deaths. (11)

In our study, the absolute risk of stillbirth in women with maternal age > 35 years old (1.3/1000) w as lower than in the Fretts study. The lower rate in our study is likely because we were able to control for a large number of covariates due to the large number of antepartum stillbirths in our cohort. Thus, maternal age > 35 years by itself was associated with a relatively low risk of stillbirth. This low risk may not apply to women > 40 years old because of the small number of women > 40 years old reaching term in our cohort. Only when maternal age was combined with other risk factors such as black race and BMI > 30 mg/m2 did the risk of stillbirth approach a level similar to that of a woman with pre-pregnancy diabetes or chronic hypertension. In addition, there is no evidence that by performing antepartum fetal testing the occurrence of stillbirth will be averted as the mechanism associated with advanced maternal age is unknown and may be unrelated to the detection of placental insufficiency.

The ability of individual risk factors of race, parity, advanced maternal age (35– 39 years old) and BMI to predict term stillbirth is poor, and this holds true even when these factors are combined. Our results do not support routine antenatal surveillance at term for any of these risk factors when present in isolation. Among multiparous women, previous preterm birth and previous cesarean delivery are risk factors for antepartum stillbirth. If a risk scoring system can be developed to identify women at the highest risk for stillbirth, then interventions such as antepartum fetal surveillance with earlier delivery if indicated may be performed to prevent the occurrence of this devastating outcome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data included in this paper were obtained from the Consortium on Safe Labor, which was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, through Contract No. HHSN267200603425C.

Footnotes

For a list of participating institutions, see the Appendix online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

References

- 1.MacDorman M, Kirmeyer S. The challenge of fetal mortality. NCHS data brief, no 16. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surkan PJ, Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Cnattingius S. Previous preterm and small-for-gestational-age births and the subsequent risk of stillbirth. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:777–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy UM, Ko CW, Willinger M. Maternal age and the risk of stillbirth throughout pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:764–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma PP, Salihu HM, Oyelese Y, Ananth CV, Kirby RS. Is race a determinant of stillbirth recurrence? Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:391–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000196501.32272.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raymond EG, Cnattingius S, Kiely JL. Effects of maternal age, parity, and smoking on the risk of stillbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:301–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson LL. Maternal medical disease: risk of antepartum fetal death. Semin Perinatol. 2002;26:42–50. doi: 10.1053/sper.2002.29838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardosi J, Kady SM, McGeown P, Francis A, Tonks A. Classification of stillbirth by relevant condition at death (ReCoDe): population based cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:1113–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38629.587639.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wisborg K, Ingerslev HJ, Henriksen TB. IVF and stillbirth: a prospective follow-up study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1312–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nohr EA, Bech BH, Davies MJ, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Prepregnancy obesity and fetal death: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:250–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172422.81496.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang DY, Usher RH, Kramer MS, Yang H, Morin L, Fretts R. Determinants of unexplained antepartum fetal deaths. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:215–21. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fretts RC, Elkin EB, Myers ER, Heffner LJ. Should older women have antepartum testing to prevent unexplained stillbirth? Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):56–64. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000129237.93777.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Branch DW, Burkman R, et al. Contemporary Cesarean Delivery Practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. Oxford University; 2003. pp. 357–402. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogberg L, Cnattingius S. The influence of maternal smoking habits on the risk of subsequent stillbirth: is there a causal relation? BJOG. 2007;114:699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Caesarean section and risk of unexplained stillbirth in subsequent pregnancy. Lancet. 2003;362:1779–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14896-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salihu HM, Sharma PP, Kristensen S, Blot C, Alio AP, Ananth CV, Kirby RS. Risk of stillbirth following a cesarean delivery: black-white disparity. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:383–90. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195103.46999.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahtiyar MO, Julien S, Robinson JN, Lumey L, Zybert P, Copel JA, et al. Prior cesarean delivery is not associated with an increased risk of stillbirth in a subsequent pregnancy: Analysis of U.S. perinatal mortality data, 1995–1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1373–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lydon-Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Nelson JC, Cárdenas V, Gardella C, Easterling TR, Callaghan WM. Accuracy of reporting maternal in-hospital diagnoses and intrapartum procedures in Washington State linked birth records. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:460–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. National vital statistics reports. 8. Vol. 57. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fretts RC, Duru UA. New indications for antepartum testing: making the case for antepartum surveillance or timed delivery for women of advanced maternal age. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:312–7. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.