Abstract

Histone gene expression is tightly coordinated with DNA replication, as it is activated at the onset of S phase and suppressed at the end of S phase. Replication-dependent histone gene expression is precisely controlled at both transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. U7 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (U7 snRNP) is involved in the 3′-end processing of nonpolyadenylated histone mRNAs, which is required for S phase-specific gene expression. The present study reports a unique function of U7 snRNP in the repression of histone gene transcription under cell cycle-arrested conditions. Elimination of U7 snRNA with an antisense oligonucleotide in HeLa cells as well as in nontransformed human lung fibroblasts resulted in elevated levels of replication-dependent H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 histone mRNAs but not of replication-independent H3F3B histone mRNA. An analogous effect was observed upon depletion of Lsm10, a component of the U7 snRNP-specific Sm ring, with siRNA. Pulse–chase experiments revealed that U7 snRNP acts to repress transcription without remarkably altering mRNA stability. Mass spectrometric analysis of the captured U7 snRNP from HeLa cell extracts identified heterogeneous nuclear (hn)RNP UL1 as a U7 snRNP interaction partner. Further knockdown and overexpression experiments revealed that hnRNP UL1 is responsible for U7 snRNP-dependent transcriptional repression of replication-dependent histone genes. Chromatin immunoprecipitation confirmed that hnRNP UL1 is recruited to the histone gene locus only when U7 snRNP is present. These findings support a unique mechanism of snRNP-mediated transcriptional control that restricts histone synthesis to S phase, thereby preventing the potentially toxic effects of histone synthesis at other times in the cell cycle.

Keywords: RNA regulator, RNA-binding protein, RNP pulldown

In eukaryotic cells, sufficient histones must be synthesized in concert with DNA replication to package the newly replicated DNA into chromatin. The expression of replication-dependent histone genes, which encode five core histone species (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4), is highly stimulated at the beginning of S phase and sharply suppressed at the end of S phase in metazoans (1). The expression of replication-dependent histone genes is coordinately activated at the transcription level at the G1/S-phase transition. The cyclin E-Cdk2 substrate p220/NPAT reportedly plays an essential role in the coordinate transcriptional activation of histone genes at the onset of S phase (2, 3). Through its direct interaction with subtype-specific transcription factors such as HiNF-P, which is required for histone H4 promoter activation (4), p220/NPAT activates histone gene transcription. The active transcription of histone genes requires ongoing DNA replication; therefore, the arrest of DNA replication with hydroxyurea or DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation leads to rapid transcriptional suppression (5, 6).

Replication-dependent histone genes produce nonpolyadenylated mRNAs that possess a conserved stem-loop (SL) structure (1, 7, 8). The noncanonical structure of the 3′ terminus of histone mRNAs significantly contributes to S phase-specific histone gene expression. Nonpolyadenylated histone mRNAs are synthesized as a consequence of the unique 3′ processing mechanism. Endonucleolytic cleavage occurs between two sequence elements, including a conserved SL structure and a purine-rich histone downstream element (HDE) that are separated by ∼15 nt (8–10).

The HDE interacts with the U7 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP), which is composed of U7 snRNA and an Sm ring. The Sm ring of U7 snRNP differs from that in spliceosomal snRNPs, containing Lsm10 and Lsm11 in place of SmD1 and SmD2 (11, 12). U7 snRNP is recruited to histone pre-mRNA primarily through base-pair formation between the 5′ end of U7 snRNA and the HDE (8, 10). The SL structure is associated with the SL-binding protein (SLBP) (13), and it stabilizes the binding of U7 snRNP to histone pre-mRNAs (14).

SLBP binds a 100-kDa zinc finger protein (ZFP100) that interacts with Lsm11 (15). SLBP is the limiting factor for S phase-specific histone mRNA synthesis (16). In mammalian cells, SLBP synthesis is activated just before entry into S phase, and phosphorylation of a specific threonine in SLBP by cyclin A/Cdk1 triggers rapid degradation at the end of S phase (16, 17). SLBP degradation leads to the destabilization of histone mRNAs, which prompts the rapid shutoff of histone gene expression at the end of S phase. Factors involved in the transcription and mRNA processing of histone genes (e.g., NPAT) are commonly localized to distinct nuclear foci, called histone locus bodies (HLBs), near the chromosomal loci of histone gene clusters. The HLBs often overlap with or are located in close proximity to the Cajal body, a classical nuclear body detected during the immunostaining of coilin (8, 18, 19).

We recently reported that the efficient depletion of U7 snRNA in HeLa cells with an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) leads to a defect in the 3′-end processing of histone mRNAs and a concomitant delay in S-phase progression (20). Cell-cycle progression was arrested at the transition step between G1 and S phase (G1/S) using a double-thymidine block for cell synchronization, and the arrested cells were used for U7 snRNA depletion. Unexpectedly, processed histone mRNAs accumulated at elevated levels, even in the absence of U7 snRNA, under cell cycle-arrested conditions. This discovery raised the intriguing possibility that U7 snRNA can suppress histone gene expression under cell cycle-arrested conditions.

In this paper, we report a unique function of U7 snRNA in histone gene expression in which U7 snRNA acts to repress transcription of replication-dependent histone genes during cell-cycle arrest. We identified heterogeneous nuclear (hn)RNP UL1 as the U7 snRNP interactor that is responsible for the repression. These data reveal dual roles of U7 snRNPs that strictly regulate histone gene expression to prevent the production of extra histones, which are harmful to the cell.

Results

Elimination of U7 snRNA Leads to the Up-Regulation of Histone Gene Expression in Cell Cycle-Arrested Cells.

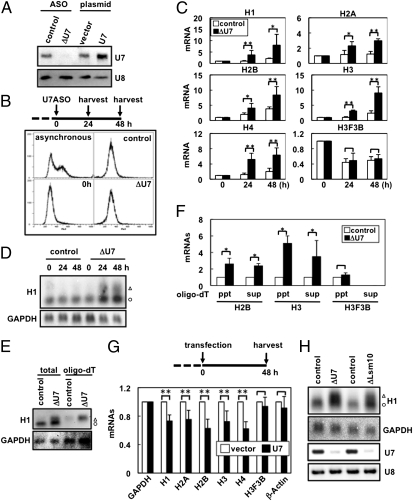

U7 snRNA was eliminated with the ASO in HeLa cells in which the cell cycle was arrested at G1/S phase using a double-thymidine block (ΔU7 cells) (lane ΔU7 in Fig. 1A). When the cell cycle-arrested period was extended for 24 or 48 h by culturing the cells in thymidine-containing media, the accumulation of matured histone H1C mRNA in ΔU7 cells was markedly elevated (eightfold) compared with accumulation in control cells (open circle in Fig. 1D). Similar up-regulation was detected in other subclasses of histone mRNAs (H1–H4) but not in H3F3B, a replication-independent histone gene that produces polyadenylated mRNA (21) (Fig. 1C). Elimination of U7 snRNA caused neither aberrant cell-cycle entry into S phase (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A) nor aberrant amplification of histone gene copy number (Fig. S1B) during extended cell-cycle arrest.

Fig. 1.

U7 snRNA acts to repress histone gene expression during cell-cycle arrest. (A) Manipulation of the intracellular level of U7 snRNA. Obliteration of U7 snRNA with knockdown with ASO (lane ΔU7) and elevation of U7 snRNA level by expression from the transfected plasmid (lane U7) were confirmed by Northern blot analysis. U8 is the control RNA. (B) Experimental time schedule of U7 ASO administration (U7 ASO) and cell harvest (harvest) is shown above. The dashed line indicates the period of cell synchronization by the addition of excess thymidine. After ASO administration, cells were cultured in thymidine-containing medium until harvest (solid line). Cell-cycle profiles of asynchronous cells and synchronized cells before (0 h) or after administration of GFP-ASO (control) or U7 ASO (ΔU7) were monitored by FACS analysis. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR to measure the levels of histone mRNAs (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) upon elimination of U7 snRNA (black bars). Levels in control cells (white bars) at 0 h are adjusted to 1.0. H3F3B is the control mRNA. (D and E) Northern blot analysis to detect histone H1C after elimination of U7 snRNA (ΔU7). Open triangles and circles represent aberrantly polyadenylated and normally processed H1C mRNAs, respectively, which were identified by Northern blot with oligo-dT–selected RNAs (E). GAPDH is the control mRNA. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR to measure the levels of polyadenylated (oligo-dT ppt) and nonpolyadenylated (oligo-dT sup) histone mRNAs upon elimination of U7 snRNA (black bars) (*P < 0.1, Student's t test). (G) The time schedule of the experiment is shown above. Histone mRNA levels in vector-transfected cells (white bars) and U7 snRNA-transfected cells (black bars) were measured by qRT-PCR. Levels in the vector-transfected cells are adjusted to 1.0. Control mRNAs are GAPDH, H3F3B, and β-actin (**P < 0.01, Student's t test). (H) U7 snRNP suppresses the expression of H1C mRNA. Northern blot analysis was performed to detect H1C mRNA and U7 snRNA in Lsm10-eliminated cells with siRNA (ΔLsm10). Aberrantly polyadenylated and normally processed H1C mRNAs are represented as in D. GAPDH and U8 are control RNAs.

The elevation of H1 mRNA detected by quantitative (q)RT-PCR was not caused by the aberrant synthesis of polyadenylated histone mRNAs in ΔU7 cells. This conclusion is evidenced by the fact that most of the increased band in the Northern blot corresponded to processed mRNAs (Fig. 1D), which were not captured by oligo(dT) selection (Fig. 1E). Moreover, qRT-PCR detected the marked increase of histone mRNA levels in the nonpolyadenylated RNA fraction (oligo dT-sups in Fig. 1F). Marked elevation of mRNA levels of the replication-dependent histone genes upon U7 snRNA depletion was observed in quiescent nontransformed fibroblasts (MRC5) (Fig. S2 A–C), indicating that the effect is not restricted to the transformed cell lines. Furthermore, when ΔU7 cells were semisynchronized with nocodazole (which arrested the cell cycle at M phase) and the cell cycle was subsequently reinitiated by the removal of nocodazole, the levels of histone mRNAs were also elevated after 8 h (Fig. S2 D and E). In contrast, a threefold up-regulation of U7 snRNA by expression from the transfected plasmid in the cell cycle-arrested cells (lane U7 in Fig. 1A) led to the down-regulation of five replication-dependent histone genes but not of the replication-independent H3F3B gene (Fig. 1G).

At the onset of S phase triggered by thymidine removal, the stimulation of histone gene expression was observed in both control and ΔU7 cells, although the elevation of mRNA levels was less remarkable in ΔU7 cells (Fig. S3). This observation indicates that the S phase-specific activation of histone gene expression per se is poorly affected by the status of cellular U7 snRNA. The higher accumulation of histone mRNAs in ΔU7 cells at S phase was likely caused by elevation of basal accumulation levels at G1/S phase. These data argue that U7 snRNA acts to repress histone gene expression under cell cycle-arrested conditions.

To exclude the possibility that the ASO for U7 snRNA knockdown artificially increased histone mRNA levels, a protein component of U7 snRNP (Lsm10) was eliminated with siRNA. U7 snRNA was obliterated in ΔLsm10 cells (Fig. 1H). Elevated accumulations of processed histone H1C mRNA and the aberrantly polyadenylated form were detected in ΔLsm10 cells (Fig. 1H). This result supports our observations in ΔU7 cells and also indicates that U7 snRNA acts as a canonical U7 snRNP with the Sm ring for the repression of histone gene expression.

U7 snRNP Represses the Transcription of Histone Genes.

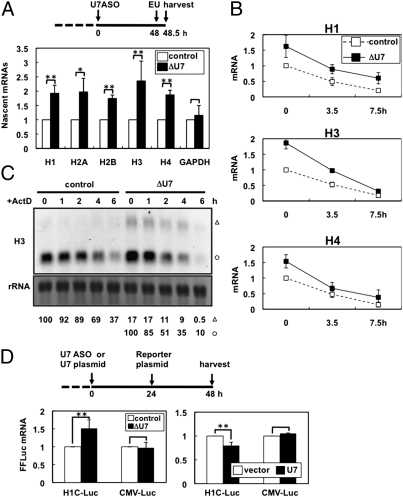

To clarify the step(s) that U7 snRNP suppresses, the levels of newly synthesized nascent histone mRNAs were measured in cell cycle-arrested ΔU7 cells and control cells. The uridine analog 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) was incorporated into cells cultured in thymidine-containing medium for 30 min, after which EU-containing nascent RNAs were captured. Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that the levels of the captured nascent mRNAs for five histone genes, but not the GAPDH gene, were markedly increased in ΔU7 cells (Fig. 2A). This finding indicates that the transcription of histone genes was stimulated by U7 snRNA depletion. We confirmed that the U7 snRNA depletion reduced or did not affect the stability of histone mRNAs by measuring the half-lives of EU pulse-labeled histone mRNAs (Fig. 2B) and unlabeled histone mRNAs after treatment with a transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D (Fig. 2C). Northern blot analysis showed that the processed forms comprised most of the accumulated H3 mRNA in ΔU7 cells (open circle in Fig. 2C), and the stability of the processed H3 mRNAs was even lower in ΔU7 cells (Fig. 2C). The processed H3 mRNA was confirmed to be nonpolyadenylated (Fig. S4A) and accurately processed at the 3′ terminus, which was identical to the position in control cells (Fig. S4B). These results indicate that the elimination of U7 snRNA leads to transcriptional derepression of replication-dependent histone genes, with neither stabilization of histone mRNAs nor alteration of mRNA processing accuracy. We further investigated whether U7 snRNP modulates transcription from histone gene promoters using the firefly luciferase (FFluc) reporter driven by the H1C promoter. Because this construct produces canonically polyadenylated FFluc mRNA, the role of U7 snRNP in transcription could be separated from its role in mRNA processing. As shown in Fig. 2D, the H1C promoter was significantly up-regulated upon depletion of U7 snRNA (Left), whereas it was slightly down-regulated in cells overexpressing U7 (Right), indicating that U7 snRNP can repress transcription from the H1C promoter.

Fig. 2.

U7 snRNP represses transcription of histone mRNAs. (A) Quantification of nascent histone mRNAs in control cells (white bars) and ΔU7 cells (black bars). EU-labeled mRNAs were quantified by qRT-PCR (*P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, Student's t test). The experimental time schedule is shown as in Fig. 1B. (B) Quantification of the stability of histone mRNAs. The degradation of pulse-labeled mRNAs was quantified in chased cells by qRT-PCR. (C) Northern blot analysis was performed to monitor the degradation of histone H3 mRNA. RNA samples were prepared from control or ΔU7 cells at different time points (0–6 h) after the addition of actinomycin D. Aberrantly polyadenylated and normally processed H3 mRNAs are represented as in Fig. 1D. Control RNA is 18S rRNA. (D) Effects of depletion and overexpression of U7 snRNA on H1C promoter activity. H1C promoter-Luc reporter (H1C-Luc) or CMV promoter-Luc reporter (CMV-Luc) was transfected into control cells or ΔU7 cells (Left) or into control cells or cells overexpressing U7 (Right). The normalized FFluc mRNA levels are plotted (**P < 0.01, Student's t test). The time schedule is the same as that shown in Fig. 1B.

hnRNP UL1 Is an Interactor of U7 snRNP.

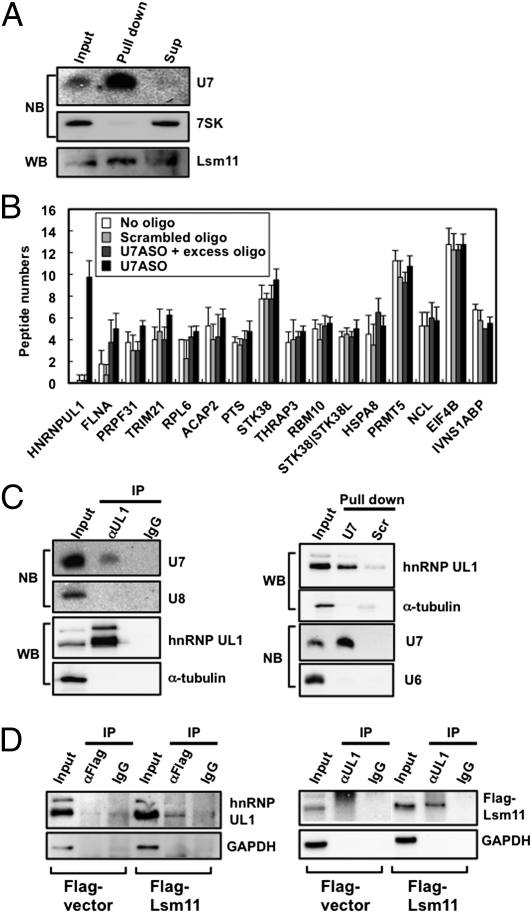

Known U7 snRNP-interacting proteins have been limited to factors involved in the 3′-end processing of histone mRNAs. Therefore, we attempted to capture U7 snRNP with the ASO to identify the responsible factor(s) for the unique function of U7 snRNP in transcriptional repression. The established method for U7 snRNP purification (22) was subjected to an antisense 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide. The identities of the proteins that were contained in the captured U7 snRNP fraction from HeLa cells were determined by highly sensitive direct nanoflow liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (23). To exclude various proteins that are nonspecifically copurified in this procedure, three control experiments were applied: (i) pull down with only beads that are not conjugated with ASOs (“no oligo” in Fig. 3B); (ii) pull down with beads that are conjugated with the ASO whose sequence was scrambled (“scrambled oligo” in Fig. 3B); and (iii) pull down with U7 ASO-conjugated beads in the presence of excess unconjugated U7 ASO (“U7ASO + excess oligo” in Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Identification of hnRNP UL1 as a U7 snRNP component. (A) Purification of U7 snRNP. U7 snRNA and Lsm11 were detected in the purified U7 snRNP fraction (pull down) by Northern blot (NB) and Western blot (WB) analyses, respectively. (B) Detected proteins in the purified U7 snRNP fraction by LC-MS analysis. Black bars indicate the analyzed numbers of peptides from the proteins, whose peptides were read more than five times, in the purified U7 snRNA fraction with ASO (U7ASO). White, light gray, and dark gray bars indicate the analyzed numbers of peptides in the three control experiments (no oligo, scrambled oligo, and U7ASO+excess oligo, respectively). (C) hnRNP UL1 is a component of U7 snRNP. Immunoprecipitation with anti-hnRNP UL1 antibody (αUL1) and IgG as a control was performed. Pull down with U7 ASO (U7) and scrambled oligo (Scr) was performed. U7 snRNA was detected by Northern blot analysis and U6 or U8 snRNA was detected as a control. hnRNP UL1 was detected by Western blot and α-tubulin was detected as a control. (D) hnRNP UL1 interacts with Lsm11, a U7 snRNP protein. (Left) Immunoprecipitation with αFlag antibody in the presence of 10 μg/mL RNase A was carried out with an extract prepared from HeLa cells transfected with either the pcDNA-Flag vector (Flag-vector) or the Flag-Lsm11 expression plasmid (Flag-Lsm11). hnRNP UL1 was detected with the αUL1 antibody. (Right) Immunoprecipitation with the αUL1 antibody was performed as on the Left. Flag-Lsm11 was detected with an anti-Flag antibody. Input samples (2% starting material) were loaded onto “Input” lanes.

Specific pull down of U7 snRNPs was confirmed by detection of U7 snRNA and Lsm11 with Northern and Western blots, respectively (Fig. 3A). The numbers of peptides identified by LC-MS analysis in the purposed experiment (U7ASO) were compared with those in the three control experiments (Fig. 3B). Among the 194 proteins detected by LC-MS analysis, most of the proteins were nonspecifically pulled down with beads, antibody, or ASO, because they appeared in the control experiments as well as in the purposed experiments. However, one protein (hnRNP UL1; also known as E1B-AP5) was specifically enriched in the fraction with U7 ASO (peptide number per analysis: 9.75) but not in the control experiments (peptide number per analysis: 0.17).

The interaction between hnRNP UL1 and U7 snRNP was confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) with an anti-hnRNP UL1 antibody (αUL1) and by pull down with U7 ASO (Fig. 3C). Northern blotting of coimmunoprecipitated RNAs with the αUL1 antibody revealed that U7 snRNA interacted with hnRNP UL1 (lane αUL1 in Fig. 3C, Left). Western blotting confirmed the coprecipitation of hnRNP UL1 during the capture of U7 snRNP with U7 ASO (lane U7 in Fig. 3C, Right). Reciprocal co-IP from HeLa cells transfected with Flag-Lsm11 revealed the interaction between hnRNP UL1 and Flag-Lsm11 in the presence of RNase A (Fig. 3D).

These data strongly suggest that hnRNP UL1 associates with U7 snRNP through protein–protein interactions with the U7-specific Sm ring or its associated factors. The protein hnRNP UL1 originally was identified as an interactor with adenovirus E1B-55K protein (24) and reportedly represses transcription from various promoters (25). These previous findings suggest the involvement of hnRNP UL1 in U7-mediated transcriptional repression.

hnRNP UL1 Is Responsible for the Unique Function of U7 snRNP.

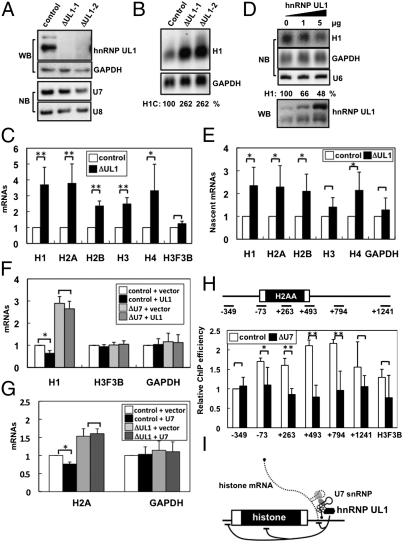

To investigate the role of hnRNP UL1 in U7 snRNP, hnRNP UL1 was eliminated from cell cycle-arrested cells cultured in thymidine-containing medium with each of two siRNAs (ΔUL1-1 and ΔUL1-2 in Fig. 4A). The elimination did not affect cell-cycle arrest at G1/S phase (Fig. S1A), nor did it alter the accumulation level of U7 snRNA (Fig. 4A). This result was distinct from the effect of Lsm10 elimination, which destabilized U7 snRNA (Fig. 1H). The accumulation of replication-dependent histone mRNAs increased upon hnRNP UL1 elimination (Fig. 4 B and C). Importantly, Northern blotting showed that hnRNP UL1 elimination did not affect the 3′-end processing of H1C mRNA (lanes ΔUL1-1 and ΔUL1-2 in Fig. 4B), which was affected in ΔU7 and ΔLsm10 cells (Fig. 1 D and H). The overexpression of hnRNP UL1 from the transfected plasmid led to the down-regulation of histone gene expression (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that hnRNP UL1 is not involved in the 3′-end processing of histone mRNAs but is required for the repression of histone gene expression. Analysis of the captured nascent histone mRNAs revealed that hnRNP UL1 elimination mediated the increase in nascent histone mRNAs (Fig. 4E), which indicates that hnRNP UL1 can repress histone gene expression at the transcriptional level.

Fig. 4.

hnRNP UL1 is the factor responsible for U7 snRNP function in the transcriptional repression of histone genes under cell cycle-arrested conditions. (A) Elimination of hnRNP UL1 does not affect U7 snRNA accumulation. hnRNP UL1 was treated with two siRNAs (ΔUL1-1 and ΔUL1-2) or control siRNA, and the elimination of hnRNP UL1 was confirmed by Western blot. U7 snRNA was detected in ΔUL1 cells by Northern blot. The siRNAs were administered into the cell cycle-arrested cells cultured in thymidine-containing medium. (B) hnRNP UL1 is not involved in the 3′-end processing of histone mRNAs but is involved in the repression of histone gene expression. Histone H1C mRNA in ΔUL1-1 and control cells was detected by Northern blot. H1C mRNA in ΔU7 cells is shown as the reference for the 3′-end processing defect. Aberrantly polyadenylated and normally processed H1C mRNAs are represented as in Fig. 1D. (C) Effects of hnRNP UL1 elimination with siRNA on histone mRNAs. Histone mRNA levels in ΔUL1-1 and control cells were quantified by qRT-PCR. (D) Overexpression of hnRNP UL1 suppresses histone H1C gene expression. The level of hnRNP UL1 in cells transfected with the expression plasmid was detected by Western blot. The plasmid amounts transfected are shown above the panel. The H1C level in hnRNP UL1-overexpressing cells was detected by Northern blotting. The quantified H1C level (normalized by GAPDH mRNA) is shown below the panel. (E) hnRNP UL1 represses the transcription of histone genes. Nascent histone mRNA levels in ΔUL1-1 and control cells were quantified by qRT-PCR. (F) Repression activity of hnRNP UL1 depends on the presence of U7 snRNA. H1 mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR by using RNA samples prepared from control and ΔU7 cells transfected with either the control vector (vector) or the hnRNP UL1 expression plasmid (UL1). (G) Repression activity of U7 snRNA depends on the presence of hnRNP UL1. H2A mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR by using RNA samples prepared from control and ΔhnRNP UL1 cells (ΔUL1) transfected with either the control vector (vector) or the U7 snRNA expression plasmid (U7). (H) ChIP of histone H2AA gene with anti-hnRNP UL1 antibody. Positions of the PCR primers used are shown above the panel. The H2AA mRNA region is boxed. ChIP levels from control or ΔU7 cells are indicated by white or black bars, respectively. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, Student's t test. (I) Model of U7 snRNP functions in histone gene expression. The curved lines below represent the repression of some steps of transcription.

To examine whether hnRNP UL1 acts as part of U7 snRNP, the repression of histone gene expression by hnRNP UL1 was monitored in the presence or absence of U7 snRNA. The repression (P < 0.05) of H1 expression by hnRNP UL1 overexpression observed in control cells was less pronounced in ΔU7 cells (Fig. 4F). Additionally, when the repression of H2A expression by U7 snRNA was monitored in the presence or absence of hnRNP UL1, the repression of H2A expression (P < 0.05) by U7 snRNA overexpression observed in control cells was less pronounced in ΔUL1 cells (Fig. 4G). Although the degree of repression was weak due to experimental limitations, the above results suggest that hnRNP UL1 acts as a part of U7 snRNP to repress histone gene expression.

The recruitment of hnRNP UL1 to the histone gene locus was monitored by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay (Fig. 4H). Replication-dependent histone genes lack introns and, therefore, cover short genomic regions (ca. 700 bp). Accordingly, the chromatin was fragmented into smaller pieces (<500 bp) than those in the usual ChIP assay to discriminate each part of the histone gene. ChIP with the αUL1 antibody and subsequent detection of histone H2AA chromatin fragments revealed the association of hnRNP UL1 with the H2AA gene locus, with peak binding occurring near the terminator of the H2AA gene. Importantly, ChIP signals were markedly weakened in ΔU7 cells (ΔU7 in Fig. 4H), which indicates that hnRNP UL1 is recruited to the histone gene locus by association with U7 snRNP.

Discussion

The tight regulation of histone gene expression during each cell cycle is required to prevent harmful effects, such as genomic instability or hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, due to the accumulation of the highly basic histones when DNA replication slows down or stops (26). Histone gene expression needs to be suppressed when the cell has passed the DNA-replication stage. We found that U7 snRNP represses histone gene expression under cell cycle-arrested conditions; this mechanism may help to prevent extra histone synthesis.

To investigate the impact of this mechanism, the levels of accumulated histones were analyzed in ΔU7 cells. Marked elevation of histone accumulation (approximately threefold) was observed when cells were treated with a proteasome inhibitor (Fig. S5). Without the treatment, histone levels were unchanged even if the levels of histone mRNAs were increased. The synthesis of extra histones from the increased mRNAs appears to be compensated by proteasome degradation in ΔU7 cells. These mechanisms of transcriptional repression and protein degradation may guarantee the prevention of extra histone synthesis. The repressive function of U7 snRNP was observed in quiescent nontransformed fibroblasts as well as in HeLa cells, suggesting that the U7 snRNP-mediated control of histone synthesis is a general regulatory mechanism adopted in various cell types.

Accurately processed histone mRNAs were detected at relatively high levels in ΔU7 cells. Although U7 snRNA depletion (to <5%) is likely to be sufficient to abolish the function of U7 snRNPs in ΔU7 cells, it cannot be ruled out that residual amounts of U7 snRNP are still able to process histone pre-mRNAs. A similar result was obtained under the condition of SLBP depletion, in which substantial levels of processed histone mRNAs accumulate in the cell (27). Another intriguing possibility is that an unidentified mechanism compensates for the 3′-end processing of histone mRNAs once a critical factor is abolished.

hnRNP UL1, the U7 snRNP-interacting protein, was recruited to the chromosomal locus of histone genes in cell cycle-arrested cells (Fig. 4H). The immunostaining results indicated that HLBs marked by NPAT were present in hnRNP UL1-localized nuclear foci in ∼15% of the cell population (Fig. S6). hnRNP UL1 has been shown to aid in transcriptional repression from various promoters, including the histone H2A promoter (25). This is consistent with the reporter assay results, which showed that U7 snRNP repressed transcription from the histone H1C promoter (Fig. 2D). The ChIP assay results revealed that the major association site of hnRNP UL1 was located near the transcription terminator of the histone H2AA gene, and that the association depended on U7 snRNA (Fig. 4H). These results suggest that hnRNP UL1 associates with U7 snRNP that binds to the nascent histone pre-mRNA, which may facilitate transcriptional repression of the cognate histone gene (Fig. 4I). Our data also suggest that the role of U7 snRNP in repression of histone gene transcription is distinct from the possible role of U7 snRNA in transcriptional control of the MDR1 gene, through interaction with the transcription factor NF-Y that binds to the MDR1 promoter (28). However, elucidation of the detailed mechanism by which hnRNP UL1 and U7 snRNP act to repress transcription will require further analysis.

The rapid transcriptional suppression of histone genes upon hydroxyurea treatment in S phase occurred properly in ΔU7 cells (Fig. S3), which indicates that the U7-mediated repression mechanism is distinct from the previously noted mechanism through the p53/p21-dependent pathway (6). Transcriptional activation of histone genes at the onset of S phase occurred normally in ΔU7 cells, which indicates that the U7-mediated repression does not affect the p220/NPAT-mediated transcriptional activation in S phase. However, how the two functions of U7 snRNP are switched depending on the cell-cycle phase remains unclear.

We have confirmed that hnRNP UL1 is associated with U7 snRNP in S phase, which indicates that the binding of hnRNP UL1 to U7 snRNP is unlikely to be the step that establishes the mode of action. Endonucleolytic cleavage to create the 3′ end of histone mRNAs is known to liberate the U7 snRNP that is used for the next round of processing (29). This observation suggests that the active transcription of histone genes in S phase facilitates the rapid turnover of U7 snRNP on the histone locus and thereby prevents hnRNP UL1 from playing a repressive function. Further mechanistic investigations regarding the role of U7 snRNP should provide unique insights into the multilayer regulatory system that maintains histone levels during each cell cycle.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Molecular Biological Protocols.

The chemicals used were purchased from Nacalai Tesque unless otherwise stated. See SI Materials and Methods for additional information.

Plasmid Construction and Transfection.

The expression plasmid of U7 snRNA was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega). The expression plasmid of Flag-Lsm11 was cloned into the pcDNA3-Flag vector (20). The expression plasmid of hnRNP UL1 was a gift from R. J. A. Grand (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK). The plasmid was administered into HeLa cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or by nucleofection with the Nucleofector device (Lonza) in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions.

Oligonucleotide Administration into Cells.

The chemically modified chimeric ASO was synthesized and administered into synchronized HeLa cells with the Nucleofector device, as described previously (20). For RNAi, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs at 200 nM (final concentration) with the Nucleofector device in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Negative control siRNA was purchased from Invitrogen. Knockdown efficiencies were verified by immunoblotting or by qRT-PCR (30). The sequences of siRNAs, ASOs, and primers for the qRT-PCR used in this study are listed in Tables S2, S3, and S4, respectively.

Cell Culture.

HeLa cells were synchronized using a double-thymidine block (31). Thymidine (2.5 mM) was added to the culture medium, incubated for 18 h, and removed. The cells were then incubated without thymidine for 10 h. A second dose of thymidine (2.5 mM) was added, and the cells were incubated for 16 h (dashed line in Figs. 1 B and G and 2 A and D and Figs. S2D and S3). Synchronized cells at G1/S phase were used for administration of nucleic acids (ASO, siRNA, and/or plasmid). The nucleic acid-treated cells were further cultured in DMEM containing 2.5 mM thymidine (bold line in Figs. 1 B and G and 2 A and D and Figs. S2D and S3). MRC5 cells were cultured in αMEM with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. The medium was exchanged with serum-free αMEM 24 h before ASO administration. The ASO-treated MRC5 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h. The cells were processed for FACS analysis of cell-cycle distribution by measuring BrdU incorporation with the FITC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Sciences) and for DNA content with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) or DAPI staining. FACS data were analyzed by Cell Lab Quanta SC software (Beckman Coulter).

Capture of Nascent RNAs.

To capture nascent RNAs, 0.5 mM EU was incorporated into the cells for 30 min. EU-labeled RNAs were biotinylated and captured by using the Click-iT Nascent RNA Capture Kit (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoprecipitation and Pull Down of Ribonucleoprotein Complex.

HeLa cells (1 × 106) were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) for 30 min on ice, and the cell extract (1 μg protein) was used for immunoprecipitation and pull-down experiments. For IP, protein complexes were precipitated with an antibody against hnRNP UL1 conjugated to Dynabeads–protein G (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. The IP products were washed four times with lysis buffer. Detailed information about the antibodies used is shown in Table S1. The pull down of U7 snRNP was carried out by using ASO as described (22). Biotinylated antisense 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide was synthesized by IDT. The ASO (400 pmol) was conjugated to Dynabeads–streptavidin T1 (Invitrogen) for 1 h in binding buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20). The ASO–Dynabeads conjugates were incubated with cell extract for 1 h at 4 °C. The captured ribonucleoprotein complexes were then washed four times with lysis buffer. The identities of the captured proteins were determined by LC-MS (23). Detailed information about the ASO sequences used is shown in Table S3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. J. A. Grand for providing the hnRNP UL1 plasmid and members of the T.H. laboratory for valuable discussions and assistance. This research was supported by the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers (NEXT Program) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization; the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders; and the Takeda Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1200523109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Marzluff WF, Wagner EJ, Duronio RJ. Metabolism and regulation of canonical histone mRNAs: Life without a poly(A) tail. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:843–854. doi: 10.1038/nrg2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma T, et al. Cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation of p220(NPAT) by cyclin E/Cdk2 in Cajal bodies promotes histone gene transcription. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2298–2313. doi: 10.1101/gad.829500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao J, et al. NPAT links cyclin E-Cdk2 to the regulation of replication-dependent histone gene transcription. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2283–2297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miele A, et al. HiNF-P directly links the cyclin E/CDK2/p220NPAT pathway to histone H4 gene regulation at the G1/S phase cell cycle transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6140–6153. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6140-6153.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sittman DB, Graves RA, Marzluff WF. Histone mRNA concentrations are regulated at the level of transcription and mRNA degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1849–1853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.7.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su C, et al. DNA damage induces downregulation of histone gene expression through the G1 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J. 2004;23:1133–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osley MA. The regulation of histone synthesis in the cell cycle. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:827–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.004143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marzluff WF. Metazoan replication-dependent histone mRNAs: A distinct set of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominski Z, Marzluff WF. Formation of the 3′ end of histone mRNA. Gene. 1999;239(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tycowski KT, Kolev NG, Conrad NK, Fok V, Steitz JA. In: The RNA World. 3rd Ed. Gesteland RF, Cech TR, Atkins JF, editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; 2006. pp. 327–368. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillai RS, Will CL, Lührmann R, Schümperli D, Müller B. Purified U7 snRNPs lack the Sm proteins D1 and D2 but contain Lsm10, a new 14 kDa Sm D1-like protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:5470–5479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pillai RS, et al. Unique Sm core structure of U7 snRNPs: Assembly by a specialized SMN complex and the role of a new component, Lsm11, in histone RNA processing. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2321–2333. doi: 10.1101/gad.274403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang ZF, Whitfield ML, Ingledue TC, III, Dominski Z, Marzluff WF. The protein that binds the 3′ end of histone mRNA: A novel RNA-binding protein required for histone pre-mRNA processing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3028–3040. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dominski Z, Zheng LX, Sànchez R, Marzluff WF. Stem-loop binding protein facilitates 3′-end formation by stabilizing U7 snRNP binding to histone pre-mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3561–3570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dominski Z, Erkmann JA, Yang X, Sànchez R, Marzluff WF. A novel zinc finger protein is associated with U7 snRNP and interacts with the stem-loop binding protein in the histone pre-mRNP to stimulate 3′-end processing. Genes Dev. 2002;16(1):58–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.932302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng L, et al. Phosphorylation of stem-loop binding protein (SLBP) on two threonines triggers degradation of SLBP, the sole cell cycle-regulated factor required for regulation of histone mRNA processing, at the end of S phase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1590–1601. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1590-1601.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koseoglu MM, Graves LM, Marzluff WF. Phosphorylation of threonine 61 by cyclin a/Cdk1 triggers degradation of stem-loop binding protein at the end of S phase. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4469–4479. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01416-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey MR, Matera AG. Coiled bodies contain U7 small nuclear RNA and associate with specific DNA sequences in interphase human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5915–5919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shopland LS, et al. Replication-dependent histone gene expression is related to Cajal body (CB) association but does not require sustained CB contact. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:565–576. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ideue T, Hino K, Kitao S, Yokoi T, Hirose T. Efficient oligonucleotide-mediated degradation of nuclear noncoding RNAs in mammalian cultured cells. RNA. 2009;15:1578–1587. doi: 10.1261/rna.1657609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albig W, et al. The human replacement histone H3.3B gene (H3F3B) Genomics. 1995;30:264–272. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith HO, et al. Two-step affinity purification of U7 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles using complementary biotinylated 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9784–9788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natsume T, et al. A direct nanoflow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry system for interaction proteomics. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4725–4733. doi: 10.1021/ac020018n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabler S, et al. E1B 55-kilodalton-associated protein: A cellular protein with RNA-binding activity implicated in nucleocytoplasmic transport of adenovirus and cellular mRNAs. J Virol. 1998;72:7960–7971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7960-7971.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kzhyshkowska J, Rusch A, Wolf H, Dobner T. Regulation of transcription by the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein E1B-AP5 is mediated by complex formation with the novel bromodomain-containing protein BRD7. Biochem J. 2003;371:385–393. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh RK, Kabbaj MHM, Paik J, Gunjan A. Histone levels are regulated by phosphorylation and ubiquitylation-dependent proteolysis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:925–933. doi: 10.1038/ncb1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan KD, Mullen TE, Marzluff WF, Wagner EJ. Knockdown of SLBP results in nuclear retention of histone mRNA. RNA. 2009;15:459–472. doi: 10.1261/rna.1205409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higuchi T, Anzai K, Kobayashi S. U7 snRNA acts as a transcriptional regulator interacting with an inverted CCAAT sequence-binding transcription factor NF-Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walther TN, Wittop Koning TH, Schümperli D, Müller B. A 5′-3′ exonuclease activity involved in forming the 3′ products of histone pre-mRNA processing in vitro. RNA. 1998;4:1034–1046. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasaki YTF, Ideue T, Sano M, Mituyama T, Hirose T. MENε/β noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2525–2530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807899106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitfield ML, et al. Stem-loop binding protein, the protein that binds the 3′ end of histone mRNA, is cell cycle regulated by both translational and posttranslational mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4188–4198. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4188-4198.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.