Abstract

Small peptides have powerful biological activities ranging from antibiotic to immune suppression. These peptides are synthesised by Non Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS). The structural understanding of NRPS took a huge leap forward in 2002, this information has lead to a number of detailed biochemical studies and further structural studies. NRPS are complex molecular machines that are composed of multiple modules. Each module contains several autonomously-folded catalytic domains. Structural studies have largely focussed on individual domains, isolated from the context of the multienzyme, and the results from these studies are discussed. Biochemical studies have looked at individual domains, isolated whole modules and intact NRPS, and combined, the data begin to allow us to visualise the process of peptide assembly by NRPS.

Introduction

Amino acids are structurally diverse and reactive molecules. The proteinogenic α-amino acids are limited to only 22 different structures. To increase the diversity and utility of these molecules, Nature has polymerised them via a peptide bond. The number of possible molecules for a peptide of length n amino acids is 22n. Large polypeptides are made using the ribosome and the post translation machinery that is familiar to anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of biology. Whilst the vast majority of peptide bond formation is catalysed by ribosomes, until recently the catalysis of peptide bond formation by NRPS has been largely overlooked. A list of molecules made by NRPS is beyond the scope of this review and the reader is referred to recent reviews for a comprehensive account of these molecules [1]. However, it is instructive to highlight some of the most well known examples to illustrate the importance of NRPS systems. The last resort antibiotic vancomycin and its analogues (Fig 1), have exquisitely complex structures made by NRPS and associated enzymes [2]. Indeed, almost all peptide based antibiotics are made by NRPS. Chelation of iron by bacteria is vital for their survival and is often a virulence determinant in pathogens. NRPS synthesise macrocycles such as enterobactin (Fig 1), which have an extraordinary high iron affinity [3]. Cyclosporin (Fig 1), an immune suppressor which made organ transplants possible and the potent anti tumour compound bleomycin (Fig 1) are both made by NRPS [4,5].

Figure 1.

Structure of NRPS molecules

A cursory examination of the structures in Figure 1 highlights the contrast between familiar ribosomal peptides and the non-ribsomal peptides. The molecules made by NRPS are often cyclic, have a high density of non-proteinogenic amino acids, and often contain amino acids connected by bonds other than peptide or disulfide bonds. Given the complexity of the molecules, one might assume that each was made by a specific pathway and very little in the way of general rules could be established. NRPS are now known to be very large proteins and, despite the obvious complexity of the products, consist of a series of repeating enzymes fused together. Such fusion of repeating enzymes in a single polypeptide closely parallels the protein machines responsible for polyketide biosynthesis [6]. For NRPS, one amino acid building block is normally incorporated into the peptide product by one module, thus products with ten amino acids would be expected to be constructed by an NRPS with ten modules stitched together. This is often termed the colinearity rule. Each module is normally specific for a particular amino acid substrate. It is important to note that there are several exceptions to the colinearity rule, particularly in NRPS that assemble siderophores [3,7,8]. The normally colinear sequence of modules in NRPS and the peptide product offers the potential for great versatility in the bioengineering of these systems.

Domains of NRPS [9]

A minimal chain elongation module contains three core domains, the condensation (C) domain, the adenylation (A) domain, and the peptidyl carrier (PCP) domain (also known as thiolation (T) domain). The A and PCP domains contain the machinery necessary to sequester an activated, covalently linked amino acid ready for peptide bond formation. Amino (and sometimes other carboxylic) acids are first activated by adenylation (by the A domain). This process consumes ATP and generates a highly reactive amino acyl adenylate (Figure 2). The adenylate reacts with a thiol at the terminus of a phosphopantetheinyl arm, which is post-translationally attached to a conserved serine residue in the PCP domain, to form an activated thioester derivative. The C domain catalyses peptide bond formation between the amino acyl thioester attached to the PCP in the same module and that of the preceding module (Fig 2). The initiation (first) module usually lacks a C domain and the last module usually contains an extra thioesterase (TE) domain (or an alternative domain such as a reductase) to cleave off the fully assembled peptide from the PCP in the final module. In addition to these essential domains, extra enzyme activities can be found within some modules. The epimerisation (E) domain, which is found after the PCP domain at the C-terminus of the module, catalyses racemisation (equilibration between L and D) of the Cα of the amino acid (either before or after peptide bond formation). The C domain can be substituted by a Cy domain, this catalyses both condensation and the intramolecular hetercyclisation of Ser, Cys or Thr (Figure 2). Methylation of the nitrogen of the amine is achieved by a methytransferase (MT) domain, which is inserted into the A domain. The TE domain cleaves the covalently tethered peptide from the NRPS by catalysing the nucleophilic attack of water (resulting in a linear peptide) or an internal nucleophile (resulting in a cyclic peptide). Initially NRPS were thought to be monomers but convincing data suggests that in some case the modules make functional dimers and that this may regulate activity [10]. This is important because dimers allow synthesis to proceed in trans (moving from one protein to chain to another) as well as in cis (moving along a single protein chain).

Figure 2.

a The modules involved in NRPS biosynthesis

b A schematic representation of the process

Figure 3.

(a) The structure of the A domain DhbE [22]. A domains bind substrate in a common pocket which is located at the interface of protein domains. The product of this reaction AMP-2,3-dihydroxybenzoate is shown in space fill.

(b) Close up of the active site highlighting the residues that contribute to the recognition of the 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. Protein engineering will have to target these residues to alter specificity. Residue numbering is from the PDB file [22].

Protein engineering prospects

A domains are usually highly selective and tolerate very little structural variation from their natural substrate (which is not necessarily a proteinogenic amino acid). For this reason, the A domain has been the subject of intense study to attempt to understand the structural basis of its selectivity [9,11-14]. The C domain has two substrate binding sites, one for the peptide attached to the PCP of the preceeding module and one for the amino acid attached to the PCP in the same module. Initially it was thought that the substrate specificity of C domains might be quite broad. This led to the hope that, as long as an amino acid can be covalently attached to a PCP domain, it would be incorporated into a fully assembled peptide product. If true, engineering need only modify or substitute the A domain to access a diverse array of peptides. Unfortunately, this may turn out not to be the case. Recent experiments suggest that the aminoacyl thioester binding site in some C domains exhibit selectivity toward the aminoacyl thioester susbtrate originating from the same module [15-17]. Although this selectivity appears to be less strict than that imposed by the A domain, it indicates that simple A domain swapping strategies are unlikely to generate truly diverse arrays of peptides. Concomittant C domain engineering may, therefore, be required making this a significant challenge. Detailed structural studies of C domains will be essential to facilitate this. Alternatively, specific modules could be linked together (each containing their cognate A, C, and PCP domains) to produce new polypeptides. This would limit their diversity by using only known A,C and PCP combinations. A final problem may arise in the last step – release of the fully assembled peptide from the NRPS - because the TE domains that typically catalyse this reaction may also exhibit substrate specificity. Accurate definition of the boundaries between modules and domains will be required for any rational engineering. Progress in “cutting out” active domains from modules has now been reported, with a C domain and TE domains being expressed in fully active form [18-21].

Adenylation domain

The A domain belongs to the adenylate forming enzyme superfamily. There are several structures of members of this superfamily, including the A domain for phenylalanine activation from the NRPS responsible for gramicidin S biosynthesis [12]. More recently a comprehensive study of DhbE has been reported [22]. DhbE is a stand alone adenylating enzyme which activates 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate (DHB) by adenylation of the carboxyl group and then catalyses formation of a thioester linkage with a PCP domain within the separately encoded DhbB protein [23]. The structure of DhbE alone, complexed with product, and complexed with both AMP and DHB, were reported [22]. The protein, in common with other members of the superfamily, has two structural domains. The large N-terminal domain is around 420 residues long and the smaller C-terminal domain accounts for the remaining 110 residues. The adenosine moiety of AMP is bound in a large cleft in the large N–terminal domain adjacent to the C-terminal domain. AMP caps the DHB binding site, suggesting DHB binding must precede productive ATP binding. DHB is bound in a similar specificity pocket to that found in PheA, located in a channel in the N –terminal domain. Sequence alignment and modelling allowed the structural basis for discrimination between the aryl acids DHB and salicylic acid by A domains to be established. These complement the existing rules established for amino acids and allow predictions of A domain substrate specificity to be made from an examination of a particular NRPS sequence [11,13]. In all three structures the orientation of the structural domains remains the same. This study seemed to rule out motion of these domains relative to each other during catalysis. Previously, the orientation of the two structural domains was thought to vary between the apo and substrate bound form during the first half reaction (adenylation). This debate has been reopened by the recently reported structures of acetyl-CoA synthetase and 4-chlororbenzoyl CoA synthetase [24,25]. Although theses are not NRPS A domains they are closely related. They have the same fold and catalyses similar chemistry. The first step is the familiar adenylation of acetate or 4-chlorobenzoate, but the second step involves transfer to the thiol of coenzyme A rather than transfer to the thiol of a PCP-bound pantethienyl arm. These structures reveal yet another orientation of the C-terminal domain with respect to the N –terminal domain. The authors of this study show evidence which suggests that this new conformation is relevant to the second catalytic reaction - transfer to thiol. Final resolution of the question will await a structure of further A domains with multiple substrates including a mimic of the pantethienyl arm.

Condensation, cyclisation and epimerisation

To date the only atomic model of a C domain derives from the structure of VibH [26]. VibH is an isolated enzyme which catalyses peptide bond formation between one of the primary amino groups of norspermidine (NS) and a PCP-bound 2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl (DHB) thioester in vibriobactin biosynthesis. The PCP domain is within the didomain protein VibB [23]. The degree of sequence conservation between VibH and conventional C domains argues that all C domains will have essentially the same structure. The C domain has two sub-domains, these sub-domains are structurally very similar leading the authors to describe this monomeric protein as “pseudodimeric”. This is, of course, consistent with the model in Figure 2, which shows that C domains bind two structurally similar substrates. As inferred from the sequence, the structure of VibH confirms that each of the sub-domains is related to enzymes within the acetyl coenzyme A-dependent acetyl transferase superfamily e.g. chlormaphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT). There is clear similarity in the chemistry catalysed by these enzymes. In essence it is the transfer of an acetyl group from a thiol to a nucleophile. In CAT, a general base His195 is required to deprotonate the primary hydroxyl group in chloramphenicol, to activate it as a nucleophile, concomitant with attack on the thioester [27]. The equivalent His in VibH can be substituted without any adverse effect on the catalytic rate [26]. The authors speculate that VibH is a special case because one of the primary amino groups of norspermidine may be deprotonated, rendering a base superfluous. Comparison of the pKa for the triprotonated form of NS (7.7) with the pH at which the assays were conducted (7.9) indicates that >50% of the norspermidine will contain one unprotonated primary amino group under the reaction conditions [28], consistent with this hypothesis. In contrast, mutation of the corresponding His within the other condensation domain required for vibriobactin biosynthesis (located within the VibF multienzyme) causes a 9-fold reduction in acylation rate for the remaining primary amino group, and a >1000-fold reduction in acylation rate for the secondary amino group, of DHB-norspermidine (the product of VibH), respectively [29]. The small reduction in the rate of acylation of the primary amino group in DHB-norsperimidine is somewhat surprising given that it would be expected to exist predominantly in the protonated form under the assay conditions. On the other hand, the fact that no vibriobactin production is observed with this mutant is unsurprising given that the secondary amino group would be essentially completely protonated. The effect of mutating the equivalent His residue in condensation domains within other, more conventional NRPS systems has also been examined [20,30]. Thus, for the C-domains within both the enterobactin synthetase EntF, which catalyses acylation of the primary amino group of a serinyl thioester with a DHB thioester, and module 2 of the tyrocidine synthetase TycB, which catalyses acylation of the secondary amino group in a prolinyl thioester with a phenylalaninyl thioester, condensation activity is significantly reduced in the mutants. To clarify the role of the conserved His residue in the catalytic mechanism of C-domains, further studies e.g. pH-rate profiles will need to be carried out.

Nucleophilic attack at the thioester forms a negatively charged tetrahedral intermediate, in the VibH structure Asn355 seemed to play a role in stabilising this, but mutagenesis suggested it was unimportant [26]. However, the equivalent residue in the enterobactin C domain does appear crucial [20]. An Asp – Arg salt bridge is crucial for the correct structure of the active site in VibH. Modelling based on the CAT structure has been used to convincingly identify the binding sites for the substrates of VibH [26]. However, these models lack the resolution to pinpoint the residues required for substrate selectivity, in particular the strong D/L selectivity exhibited by these domains [15-17].

The Cy domain substitutes for the C domain in several NRPS [1,9]. Thus the Cy domain has a gain of function in that after condensation it can cyclise either a Cys, Ser, or Thr residue to make the corresponding thiazoline or oxazaline ring. It is no surprise that the Cy domain is very similar in sequence to the C domain, since both catalyse condensation of two covalently linked amino acids. No structure of a Cy domain is currently available, but a recent biochemical study has demonstrated that the uncyclised peptide is an intermediate in the heterocyclisation reaction, implying the same initial reactions are catalysed by the C and Cy domains [31].

Although E domains are very likely to have a similar fold to VibH, they cannot substitute for C domains. Quite why E domains should consist of two sub-domains is unclear when they act on a single substrate. The structure of VibH suggests that one sub domain may be closed off by a loop, indicating that evolution has perhaps derived the activity from a C domain. There is some interesting questions regarding the catalytic mechanism of E domains. They can catalyse epimerisation either before or after condensation. The timing depends on whether the domain is located in a chain initiation or a chain elongation module [32,33]. The highly conserved His that acts as a catalytic base in C domains is also highly conserved in E domains and would seem an obvious choice of general base for Cα deprotonation. This suggestion is highly plausible given that the pKa of the primary hydroxyl group in chloramphenicol (~16) that is acetylated with acetyl CoA by CAT is likely to be very similar to that of the α-proton in an aminoacyl thioester. Recent mutagenesis experiments on the tyrocidine synthetase system confirm that this conserved His residue is required for the epimerisation reaction [34]. Additional catalytic residues, in particular a general acid, may be required in addition to those present in C domains depending on whether epimerisation occurs via a one base or a two base mechanism and whether a planar enolate intermediate is involved. Biochemical data are consistent with a two base mechanism involving a planar intermediate [34]. Structural studies will play a key role in identifying additional catalytic residues, defining the catalytic mechanism and understanding the mechanisms of substrate selectivity in E domains.

Recently, biochemical studies have established that racemisation of aminoacyl thioester intermediates in at least one NRPS is achieved without a canonical E domain. Instead, pyochelin synthetase uses a modified methytransferase domain to accomplish racemisation [35]. There is a satisfying chemical link between the racemisation and methyl transfer reactions, both require the generation of a carbanion α to the keto function. For methyl transfer, the carbanion is the nucleophile which decomposes S-adenosyl methionine, but for the novel racemisation domain, a proton simply adds to the carbanion in an uncatalysed step, giving a racemic mixture. However, since protonation / deprotonation is reversible and only the desired isomer is utilised by the downstream condensation domain, only a single optical isomer results in the product. This strategy of optical isomer selection has also been seen for conventional E domains [32,33].

Thioesterase (TE)

There are two types of TE associated with NRPS. The first is usually found as the last domain in the type I NRPS multienzymes and catalyses cleavage of the assembled peptide product from the PCP domain in the last module. The structure of a TE domain from the NRPS responsible for surfactin A biosynthesis has been determined by two groups [19] [21]. Unsurprisingly, the fold of the TE domain belongs to the α,β-hydrolase family, with the conventional catalytic triad Ser, His and Asp. The first step of the reaction is the same as that catalysed by most hydrolases, the formation of a tetrahedral enzyme linked intermediate (Fig4) in which the negative charge is stabilised by an oxyanion hole. In surfactin A biosynthesis, the intermediate is decomposed by loss of the phosphopantetheinyl thiol to give an acyl enzyme intermediate which subsequently undergoes nucleophilic attack by an internal nucleophile (hydroxyl group). This step is always in competition with hydrolysis. Based on the structure of the isolated TE domain complexed with a boronic acid adduct and the NMR structure of surfactin A, a model of the peptidyl thioester bound to the active site was proposed [19]. The structure suggests only the last two residues (Leu 7 and Leu 6, adjacent to the thioester) are recognised by the protein. Their requirement for efficient macrocyclisation has been confirmed by biochemical studies. The remaining residues in surfactin, with the exception of the first residue (Glu), when varied can still be macrocyclised by the isolated TE domain [19]. The structure does not reveal why Glu1 is required. As would be expected the positioning of the nucleophile, which depends significantly on the conformation of the peptide, is crucial for achieving efficient macrocyclisation. This was confirmed by testing peptidyl thioesters analogues with different conformational properties as substrates for the isolated TE domain. These underwent hydrolysis in preference to cyclisation. Interestingly the Glu1 residue in the substrate seems to be required for cyclisation but not hydrolysis and has been suggested to activate the incoming intramolecular nucleophile, although in the structure it seems too far away from Leu7 to accomplish this. Studies on TE domains that catalyse hydrolysis are relatively rare.

Figure 4.

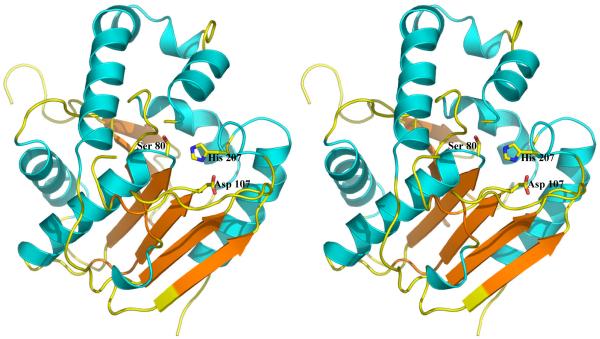

The structure of VibH, a condensation domain [26]. The residues identified by mutagenesis to be important for catalysis are shown. His 126 is not required for VibH catalysis although this may be a feature of its nucleophilic substrate, the residues is required in other C domains.

Stand alone Type II thioesterases are often found encoded within NRPS gene clusters but apparently do not play an essential role in peptide synthesis, because their removal decreases product titres but does not completely abolish product synthesis [36]. These thioesterases are likely to belong to the α,β-hydrolase fold family, but it appears they work on very different substrates than the type I TEs. Initially they were thought to cleave off incorrectly loaded amino acids from PCP domains, but more recent work suggests their role is to hydrolytically remove inactivating acetyl groups from the 4′-phosphopantetheine thiols of PCP domains (originating from the utilisation of acetyl CoA instead of coenzyme A in the posttranslational modification of PCP domains) to regenerate active free thiol groups [37].

Future prospects

In the past three years structural work has begun to map out NRPS. An atomic model for each of the component core modules now exists. In particular our understanding of A domains is now detailed enough for theoretical predictions to be made about their susbstrate specificities. Similar understanding is still somewhat lacking for the related C, Cy and E domains. Although a model exists for the fold, there are no co-complexes and thus no detailed information regarding substrate recognition. Biochemical studies on the mechanism of condensation, suggest that, although there is a conserved set of residues involved in catalysis, their importance for catalysis depends on the precise nature of the substrate. Examples of fully functional domains being expressed outside the context of the module have been reported, and in the short term, it would appear likely that structural studies will focus on these to answer questions of recognition and catalysis. Whether or not intact modules, much less mutli modular NRPS, which inherently need to be flexible, can ever be crystallised is an open question. At present, a key challenge is to express such large proteins in sufficient amounts for EM studies, which perhaps hold the best hope of visualising the entire machinery. Fourier transform mass spectrometry has been shown to be useful for characterising the covalent intermediates on hybrid PKS-NRPS multienzymes [38,39]. In the short term, it seems likely that this powerful technique will facilitate characterisation of the various intermediates as they are assembled on these multienzymes. Combining the data from these different techniques should eventually produce an atomic model for these large scale protein machines.

Figure 5.

Thioesterase domain of surfactin synthetase [21]. The catalytic residues are shown. The helical structure provides recognition for residues adjacent to the cleavage site. The protein does not recognise residues far from the cleavage site. The coordinates for the co-complex are not yet available [19].

References

- 1.Konz D, Marahiel MA. How do peptide synthetases generate structural diversity? Chemistry & Biology. 1999;6:R39–R48. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Wageningen AMA, Kirkpatrick PN, Williams DH, Harris BR, Kershaw JK, Lennard NJ, Jones M, Jones SJM, Solenberg PJ. Sequencing and analysis of genes involved in the biosynthesis of a vancomycin group antibiotic. Chemistry & Biology. 1998;5:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gehring AM, Mori I, Walsh CT. Reconstitution and characterization of the Escherichia coli enterobactin synthetase from EntB, EntE, and EntF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2648–2659. doi: 10.1021/bi9726584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber G, Schorgendorfer K, Schneiderscherzer E, Leitner E. The Peptide Synthetase Catalyzing Cyclosporine Production in Tolypocladium-Niveum Is Encoded by a Giant 45.8-Kilobase Open Reading Frame. Current Genetics. 1994;26:120–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00313798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du LC, Sanchez C, Chen M, Edwards DJ, Shen B. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor drug bleomycin from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003 supporting functional interactions between nonribosomal peptide synthetases and a polyketide synthase. Chemistry & Biology. 2000;7:623–642. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cane DE, Walsh CT. The parallel and convergent universes of polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chemistry & Biology. 1999;6:R319–R325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller DA, Luo LS, Hillson N, Keating TA, Walsh CT. Yersiniabactin synthetase: A four-protein assembly line producing the nonribosomal peptide/polyketide hybrid siderophore of Yersinia pestis. Chemistry & Biology. 2002;9:333–344. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu SW, Fiss E, Jacobs WR. Analysis of the exochelin locus in Mycobacterium smegmatis: Biosynthesis genes have homology with genes of the peptide synthetase family. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180:4676–4685. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4676-4685.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lautru S, Challis GL. Substrate recognition by nonribosomal peptide synthetase multi-enzymes. Microbiology-Sgm. 2004;150:1629–1636. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillson NJ, Walsh CT. Dimeric structure of the six-domain VibF subunit of vibriobactin synthetase: Mutant domain activity regain and ultracentrifugation studies. Biochemistry. 2003;42:766–775. doi: 10.1021/bi026903h. [•• First experimental evidence of a dimeric arrangement of NRPS modules. This opens up the possibility of cis and trans action in NRPS.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challis GL, Ravel J, Townsend CA. Predictive, structure-based model of amino acid recognition by nonribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domains. Chemistry & Biology. 2000;7:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti E, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel MA, Brick P. Structural basis for the activation of phenylalanine in the non-ribosomal biosynthesis of gramicidin S. Embo Journal. 1997;16:4174–4183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. The specificity-conferring code of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chemistry & Biology. 1999;6:493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eppelmann K, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel MA. Exploitation of the selectivity-conferring code of nonribosomal peptide synthetases for the rational design of novel peptide antibiotics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9718–9726. doi: 10.1021/bi0259406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clugston SL, Sieber SA, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Chirality of peptide bond-forming condensation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases: The C-5 domain of tyrocidine synthetase is a C-D(L) catalyst. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12095–12104. doi: 10.1021/bi035090+. [•Evidence that the C domains are not passive acceptors of whatever is loaded on an A domain.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belshaw PJ, Walsh CT, Stachelhaus T. Aminoacyl-CoAs as probes of condensation domain selectivity in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Science. 1999;284:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehmann DE, Trauger JW, Stachelhaus T, Walsh CT. Aminoacyl-SNACs as small-molecule substrates for the condensation domains of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chemistry & Biology. 2000;7:765–772. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trauger JW, Kohli RM, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Peptide cyclization catalysed by the thioesterase domain of tyrocidine synthetase. Nature. 2000;407:215–218. doi: 10.1038/35025116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tseng CC, Bruner SD, Kohli RM, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT, Sieber SA. Characterization of the surfactin synthetase C-terminal thioesterase domain as a cyclic depsipeptide synthase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13350–13359. doi: 10.1021/bi026592a. [•• Structure of thioesterase domain with bornate mimic of substrate. This reveals the selectivity code for the thioesterase domain is both sequence and structure of the NRPS.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche ED, Walsh CT. Dissection of the EntF condensation domain boundary and active site residues in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1334–1344. doi: 10.1021/bi026867m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruner SD, Weber T, Kohli RM, Schwarzer D, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT, Stubbs MT. Structural basis for the cyclization of the lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin by the thioesterase domain SrfTE. Structure. 2002;10:301–310. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00716-5. [• The first structure of thioesterase domain] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May JJ, Kessler N, Marahiel MA, Stubbs MT. Crystal structure of DhbE, an archetype for aryl acid activating domains of modular nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:12120–12125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182156699. [• The most recent A domain structure, in this case an aryl acid rather than an amino acid is recognised. The paper details the molecular recognition involved by producing a series of structures.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating TA, Marshall CG, Walsh CT. Reconstitution and characterization of the Vibrio cholerae vibriobactin synthetase from VibB, VibE, VibF, and VibH. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15522–15530. doi: 10.1021/bi0016523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulick AM, Starai VJ, Horswill AR, Homick KM, Escalante-Semerena JC. The 1.75 A crystal structure of acetyl-CoA synthetase bound to adenosine-5 ′-propylphosphate and coenzyme A. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2866–2873. doi: 10.1021/bi0271603. [•• See 25] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gulick AM, Lu XF, Dunaway-Mariano D. Crystal structure of 4-chlorobenzoate : CoA ligase/synthetase in the unliganded and aryl substrate-bound states. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8670–8679. doi: 10.1021/bi049384m. [•• These studies detail work on a protein related to the A domain. The work suggests a complex series of conformation changes in the sub domains of the A domain occur during catalysis. This provides an insight into how the A domain might function as part of intact NRPS molecule.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keating TA, Marshall CG, Walsh CT, Keating AE. The structure of VibH represents nonribosomal peptide synthetase condensation, cyclization and epimerization domains. Nature Structural Biology. 2002;9:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nsb810. [•• The first structure of a condensation domain. In the paper modelling is used to predict how the substrates are bound by the enzyme.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewendon A, Murray IA, Shaw WV, Gibbs MR, Leslie AGW. Replacement of Catalytic Histidine-195 of Chloramphenicol Acetyltransferase - Evidence for a General Base Role for Glutamate. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1944–1950. doi: 10.1021/bi00173a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergeron RJ, Seligsohn HW. Hexahydropyrimidines as Masked Spermidine Vectors in Drug Delivery. Bioorganic Chemistry. 1986;14:345–355. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall CG, Hillson NJ, Walsh CT. Catalytic mapping of the vibriobactin biosynthetic enzyme VibF. Biochemistry. 2002;41:244–250. doi: 10.1021/bi011852u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergendahl V, Linne U, Marahiel MA. Mutational analysis of the C-domain in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2002;269:620–629. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duerfahrt T, Eppelmann K, Muller R, Marahiel MA. Rational design of a bimodular model system for the investigation of heterocyclization in nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Chemistry & Biology. 2004;11:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo LS, Burkart MD, Stachelhaus T, Walsh CT. Substrate recognition and selection by the initiation module PheATE of gramicidin S synthetase. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:11208–11218. doi: 10.1021/ja0166646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo LS, Kohli RM, Onishi M, Linne U, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Timing of epimerization and condensation reactions in nonribosomal peptide assembly lines: Kinetic analysis of phenylalanine activating elongation modules of tyrocidine synthetase B. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9184–9196. doi: 10.1021/bi026047+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stachelhaus T, Walsh CT. Mutational analysis of the epimerization domain in the initiation module PheATE of gramicidin S synthetase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5775–5787. doi: 10.1021/bi9929002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel HM, Tao JH, Walsh CT. Epimerization of an L-cysteinyl to a D-cysteinyl residue during thiazoline ring formation in siderophore chain elongation by pyochelin synthetase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10514–10527. doi: 10.1021/bi034840c. [•• Demonstrates that methyltransferase-like domains as well as epimerisation domains can be involved in epimeristion at the α-carbon] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider A, Marahiel MA. Genetic evidence for a role of thioesterase domains, integrated in or associated with peptide synthetases, in non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Archives of Microbiology. 1998;169:404–410. doi: 10.1007/s002030050590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarzer D, Mootz HD, Linne U, Marahiel MA. Regeneration of misprimed nonribosomal peptide synthetases by type II thioesterases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:14083–14088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212382199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hicks LM, O’Connor SE, Mazur MT, Walsh CT, Kelleher NL. Mass spectrometric interrogation of thioester-bound intermediates in the initial stages of epothilone biosynthesis. Chemistry & Biology. 2004;11:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazur MT, Walsh CT, Kelleher NL. Site-specific observation of acyl intermediate processing in thiotemplate biosynthesis by Fourier transform mass spectrometry: The polyketide module of yersiniabactin synthetase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13393–13400. doi: 10.1021/bi035585z. [• Illustrates the application of the very high mass resolution obtainable with FTICR mass spectrometry to direct observation of intermediates in the assembly process covalently attached to NRPS PCP domains.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]