Abstract

Individuals consume alcohol for a variety of reasons (motives), and these reasons may be differentially associated with the types of drinking outcomes that result. The present study examined whether specific affect-relevant motivations for alcohol use (i.e., coping, enhancement) are associated with distinct types of consequences, and whether such associations occur directly, or only as a function of increased alcohol use. It was hypothesized that enhancement motives would be associated with distinct problem types only through alcohol use, whereas coping motives would be linked directly to hypothesized problem types. Regularly drinking undergraduates (N= 192, 93 female) completed self-report measures of drinking motives and alcohol involvement. Using structural equation modeling, we tested direct associations between Coping motives and indirect associations between Enhancement motives and eight unique alcohol problem domains: Risky Behaviors, Blackout Drinking, Physiological Dependence, Academic/Occupational problems, Poor Self-care, Diminished Self-perception, Social/Interpersonal problems, and Impaired Control. We observed direct effects of Coping motives on three unique problem domains (Academic/Occupational problems, Risky Behaviors, and Poor Self-care). Both Coping and Enhancement motives were indirectly associated (through Use) with several problem types. Unhypothesized associations between Conformity motives and unique consequence types also were observed. Findings suggest specificity in the consequences experienced by individuals who drink to cope with negative affect versus to enhance positive affect, and may have intervention implications. Findings depict the coping motivated student as one who is struggling across multiple domains, regardless of levels of drinking. Such students may need to be prioritized for interventions.

Keywords: drinking motives, alcohol-related consequences, college students

Many college students drink alcohol heavily (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2005). The types of negative alcohol consequences that they thus may encounter range from relatively mild (e.g., vomiting, Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) to more severe (e.g., physiological dependence) as heavy drinking continues (Chung & Martin, 2002; Jennison, 2004; O'Neill & Sher, 2000; Vik, Carrello, Tate, & Field, 2000). A focus on the antecedents of specific types of alcohol problems could inform targeted preventive interventions.

Social Learning Theory (SLT; Bandura, 1977, 1986; Maisto, Carey, & Bradizza, 1999) offers a comprehensive framework through which to understand alcohol use and consequences. SLT suggests that cognitive factors are important mechanistic predictors of behavioral outcomes (e.g., drinking consequences), and a common pathway through which more distal factors exert influence (Sher, Trull, Bartholow, & Vieth, 1999). One cognitive variable widely observed to be proximally important to drinking is motivation for drinking (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel & Engels, 2005). Among the many factors that may motivate drinking, the regulation of affect is a prominent one (Cox & Klinger, 1990; Lang, Patrick, & Stritzke, 1999; Wills & Shiffman, 1985). As such, motivational models typically have integrated affect. The literature is marked by a diverse range of drinking motives models. Each acknowledges the importance of affect in motivation, and includes three (e.g., Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992), four (Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988), and, more recently, five dimensional models (Grant, Stewart, O'Connor, Blackwell, & Conrod, 2007).

In the present study we used a four dimensional approach, examining Enhancement, Coping, Social Reinforcement and Conformity motives (Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988). In this model, both Social and Enhancement motives involve positive reinforcement, but are distinguished by whether reinforcement is internal (i.e., Enhancement motives; to augment positive emotional states), or external (i.e., Social motives; to obtain social benefits). Similarly, both Coping and Conformity motives involve negative reinforcement, but the reinforcement is internal for Coping (i.e., to reduce negative emotions) and external for Conformity motives (i.e., to avoid social rejection; Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988). Certainly all four of these motivations might constitute pathways to alcohol consequences consistent with SLT (see Maisto et al., 1999). Yet, this theory and others (e.g., Affect Regulation Models; Wills & Shiffman, 1985) as well as data (Carey & Correia, 1997; Cooper et al., 1992; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000; Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007) point to the unique risk for problem alcohol involvement associated with coping and enhancement motives. Accordingly, here we focus primarily on those internally reinforcing (i.e., affectively based) motives.

Clearer delineation of affectively-based motives as antecedents to unique consequence types may offer specificity in targeting individuals for intervention, and may inform personalized feedback given to problem drinkers. Yet few studies have examined the association between drinking motives and specific alcohol outcomes (Bradley, Carman, & Petree, 1992; Karwacki & Bradley, 1996; Martens, Cox, & Beck, 2003). Thus, the present study was designed to extend previous research (e.g., Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; Magid et al., 2007; Martens et al., 2003; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001) by elucidating SLT-based motivational pathways to specific consequence domains.

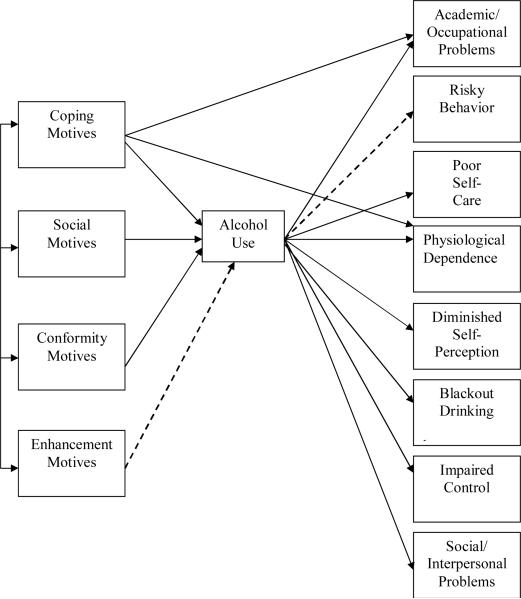

We also aimed to understand whether coping and enhancement motives could be differentiated based on whether their associations with unique alcohol problem were direct, or occurred by way of increased alcohol use. Based on previous research (Carey & Correia, 1997; Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988; Cooper et al., 1995; Magid et al., 2007; Read et al., 2003) we hypothesized that Coping motives would be directly associated with specified problem types (i.e., above and beyond levels of alcohol use), while Enhancement motives would be indirectly associated with problems. Guided by previous empirical findings, we expected to observe direct associations between Coping motives and three problem domains (Figure 1): Risky Behaviors (e.g., Cooper et al., 2000; Martens et al., 2003), Academic/Occupational impairment (Bradley, Carman, & Petree,1991; Cooper et al., 1992; Windle & Windle, 1996), and Physiological Dependence (Carpenter and Hasin, 1998, a, b; Carpenter and Hasin, 1999; Cooper et al., 1992; Kassel et al., 2000). We also posited that Enhancement motives would be (indirectly) associated with Risky Behaviors; as when drinking for enhancement, lowered inhibition may facilitate engaging in risky behaviors (Cooper, 2000).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model. Note: Dotted lines represent the hypothesized indirect path, solid lines represent hypothesized direct paths.

Method

Participants and Procedure

An initial pool of 206 participants was recruited via a mass testing procedure in introductory psychology classes at a mid-sized university in the northeastern United States. Eligible participants (ages 18 to 24) drank alcohol at least once a week (past 3 months). One participant did not meet inclusionary age criteria, two withdrew, and eleven had incomplete or missing data. Thus, the final sample was 192 (93 females). The majority (n = 169, 88%) were Caucasian and just under half (n = 95, 49%) were freshmen. The average age was 19.1 (SD = 1.2).

Study procedures were approved by the university's Institutional Review Board. Data were collected as part of a larger experimental study of mood and expectancy activation which included a random assignment to a positive, negative, or neutral mood induction followed by a reaction time task involving alcohol expectancies. Following the end of this session (approximately ½ hour later), participants completed self-report measures (including those for the present study, outlined below). Complete sessions lasted 1.5 hours, after which participants were debriefed and received their choice of either academic credit or $15. Informed consent was obtained prior to session start.

Measures

Alcohol Use

Daily use was assessed with the calendar-based Time Line Follow Back method (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell, 1992). The term “standard drink” was operationalized before participants were interviewed regarding the number of drinks they consumed and over what number of hours, for the previous 60 days. Data from this interview were used to calculate typical quantity, frequency, and frequency of heavy episodic drinking (i.e., 4+/5+ drinks [males/females]). We also calculated estimated daily Blood Alcohol Concentrations (eBACs; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, Marlatt, (1999). Daily BACs were averaged across drinking days. On average, participants drank just less than twice weekly (SD = 0.92), consumed 6.59 drinks per drinking day (SD = 2.73), reported heavy episodic drinking on 5.54 occasions per month (SD = 3.50), and had an eBAC of .11 (SD=.06). These four alcohol use measures each were standardized (M = 0, SD = 1), and their unweighted average was computed. This composite allowed us to capture the multidimensional nature of alcohol use (Sobell & Sobell, 1992).

Drinking motives

Using Cooper's (1994) 20-item scale, respondents rated frequency of drinking for each reason on a Likert scale from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). Subscale scores were created by summing the five items on each subscale. Cronbach's alphas were .84 (Coping), .84 (Enhancement), .87 (Social), and .85 (Conformity).

Alcohol-related consequences

The 48-item Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read et al., 2006) assesses eight consequence domains, which load on a higher-order factor. Domains include Social/Interpersonal (6 items, α = .82), Academic/Occupational (5 items, α = .79), Risky Behavior (8 items, α = .80), Impaired Control (6 items, α = .81), Poor Self-Care (8 items, α = .84), Diminished Self-Perception (4 items, α = .90), Blackout Drinking (7 items, α = .89), and Physiological Dependence (4 items, α = .70). Response options are dichotomous.

Results

See Table 1 for intercorrelations and descriptives. Prior to substantive analyses, univariate distributions were examined to identify significant skewness or kurtosis. “Far outliers” were set to 1 value greater than the largest non-far-outlying value (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). The hypothesized path model, tested using MPlus Version 5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007), is presented in Figure 1. Covariances were estimated among the alcohol problem domains, and to control for shared variance, among all drinking motives. Model fit was considered good if the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were greater than .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was less than .06 and the χ2 / df ratio was less than 3.0 (Kline, 1998).

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cope | 1 | 9.62 | 3.99 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Enh | .40** | 1 | 15.93 | 4.72 | |||||||||||

| 3. Conf | .21** | .21** | 1 | 7.27 | 3.06 | ||||||||||

| 4. Soc | .44** | .61** | .32** | 1 | 17.04 | 4.37 | |||||||||

| 5. Use | .02 | .39** | .07 | .29** | 1 | 0.00 | 0.76 | ||||||||

| 6. Soc/Int | .26** | .20** | .10 | .23** | .17* | 1 | 2.45 | 1.47 | |||||||

| 7. Cont | .21** | .23** | .31** | .27** | .22** | .42** | 1 | 2.01 | 1.45 | ||||||

| 8. Self-p | .19** | −.07 | .21** | .05 | −.18** | .38** | .37** | 1 | 0.82 | 1.23 | |||||

| 9. Self-c | .34** | .21** | .29** | .22** | .12 | .39** | .48** | .34** | 1 | 1.31 | 1.54 | ||||

| 10. Risk | .24** | .29** | .18** | .28** | .24** | .56** | .38** | .17* | .27** | 1 | 2.54 | 1.80 | |||

| 11. Ac/Oc | .23** | .21** | .15* | .25** | .25** | .44** | .49** | .24** | .39** | .33** | 1 | 1.03 | 1.19 | ||

| 12. Dep | .17* | .20** | .12 | .25** | .37** | .27** | .35** | .10 | .32** | .32** | .39** | 1 | 0.53 | 0.63 | |

| 13. Blk | .24** | .38** | .27** | .36** | .21** | .32** | .40** | .19** | .24** | .38** | .36** | .30** | 1 | 4.29 | 1.91 |

Notes: Cope = Coping motives; Enh = Enhancement motives; Conf = Conformity motives; Soc = Social motives; Use = Alcohol Use; Total Probs = Total Alcohol Problems; Soc/Int = Social/Interpersonal problems; Cont = Impaired Control; Self-p = Diminished Self-perception; Self-c = Poor Self-care; Risk = Risky Behaviors; Ac/Oc = Academic/Occupational problems; Dep = Physiological Dependence; Blk = Blackout drinking; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

p≤.05

p≤.01.

The hypothesized model (75 free parameters) did not fit the data well (χ2 (29) = 85.79, χ2 / df = 2.96; TLI = .73; CFI = .89, RMSEA = .10). Though we had a priori hypotheses, given that no prior research has tested all four motives as predictors of the eight unique problem domains in a single model, we used modification indices (MIs) to guide model re-specification. A cutoff of MI=4.0 was chosen, as a change in the model chi-square of 3.84 should be exceeded at the .05 level for one degree of freedom in order to reject the null hypothesis. Paths that were not plausible or that were not supported by theory or previous research (e.g., from one problem type to another or to a drinking motive) were not added, regardless of MIs. This approach resulted in the addition of paths from Coping motives to Self-care and Social/Interpersonal problems; from Enhancement motives to Blackouts; and from Conformity motives to Impaired Control, Self-care, Self-perception, and Blackouts. Our respecified model (82 free parameters) provided excellent fit (χ2 [22] = 25.85, χ2 / df = 1.18; TLI = .98; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03), and was significantly better than the hypothesized model (Δχ2 = 59.94, Δdf = 7, p < .001). Given the empirically driven nature of the respecifications (i.e., paths were added based on their potential contribution to overall model fit), we determined a priori that, non-hypothesized paths would be evaluated at p<.01 to reduce the likelihood of capitalization on chance; paths originally hypothesized consistent with theory and prior research were evaluated at a p ≤ .05 significance level.

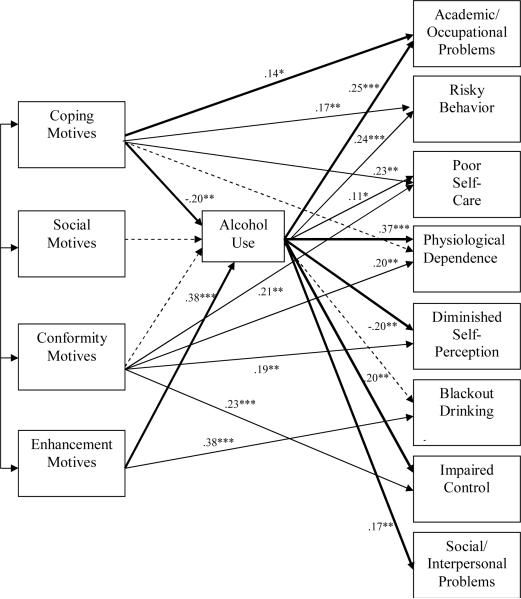

As hypothesized, direct paths were observed from both Coping and Enhancement motives to Alcohol Use, and from Use to several problem domains (Figure 2). Also as hypothesized, Coping motives were directly associated with Academic/Occupational problems and Risky Behaviors. Though not hypothesized, we observed significant direct associations between Coping motives and Poor Self-Care, and Enhancement motives and Blackouts. A few unexpected direct paths from Conformity motives to problem types also emerged (see Figure 2). The respecified model accounted for 19% of the variability in Use, 13% in Self-care, 7% in Self-perception, 10% in Impaired Control, 6% in Social/Interpersonal problems, 9% in Academic/Occupational problems, 16% in Blackout Drinking, 15% in Dependence, and 9% in Risky Behaviors.

Figure 2.

Respecified model. Note: Standardized path coefficients are depicted. * p≤ .05, **p≤.01, ***p≤.001. Bold lines indicate hypothesized paths that were significant, solid lines indicate non-hypothesized paths that were significant, dashed lines indicate hypothesized paths that were non-significant.

To test the significance of the proposed indirect paths, we applied the bias-corrected bootstrap method (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Results are summarized in Table 2. Applying 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to evaluate hypothesized indirect associations and 99% CIs for non-hypothesized associations, there were significant indirect associations (through alcohol use) of Enhancement motives on Social/Interpersonal Problems, Impaired Control, Self-perception, Dependence, Academic/Occupational problems, and as hypothesized, Risky Behaviors. We also observed (negative) indirect associations between Coping motives and Academic/Occupational problems, Impaired Control, Risky Behaviors, and Dependence.

Table 2.

Significant indirect effects of Coping and Enhancement motives on unique alcohol-related problems

| Indirect Effect | 95% CI | 99% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant Hypothesized Path (Evaluated with the 95% CI) | |||

| Enh→Use→Risk | .035 | (.015, .067) | (.009, .077) |

| Significant Non-hypothesized Paths (Evaluated with the 99% CI) | |||

| Enh→Use→Ac/Oc | .024 | (.012, .044) | (.009, .049) |

| Enh→Use→Soc | .020 | (.007, .042) | (.002, .045) |

| Enh→Use→Cont | .023 | (.008, .041) | (.004, .049) |

| Enh→Use→Self-p | −.020 | (−.038, −.005) | (−.045, −.001) |

| Enh→Use→Dep | .019 | (.009, .031) | (.009, .034) |

| Cope→Use→Ac/Oc | −.015 | (−.028, −.005) | (−.035, −.001) |

| Cope→Use→Dep | −.011 | (−.022, −.003) | (−.027, −.001) |

| Cope→Use→Cont | −.014 | (−.032, −.004) | (−.038, −.001) |

| Cope→Use→Risk | −.021 | (−.044, −.005) | (−.052, −.001) |

Note: Indirect effects are presented as unstandardized coefficients. CI = Confidence Interval; Enh = Enhancement motives; Cope = Coping motives; Use = Alcohol Use; Self-P = Diminished Self-perception; Cont = Impaired Control; Soc = Social/Interpersonal problems; Ac/Oc = Academic/Occupational problems; Dep = Physiological Dependence; Risk = Risky Behaviors

Discussion

These data suggest that the two drinking motives related to the regulation of affect are differentially associated with, and account for nontrivial variability in, specific alcohol consequences. This study also sheds light on the manner in which these motivational pathways may lead to alcohol problem types. Below, we comment on specific pathways and what they may mean for understanding associations between drinking motivation and unique alcohol problems.

The Role of Coping Motives

Extending previous research in which direct effects of coping motives on broad alcohol problem indices have been observed (Carey & Correia, 1997; Cooper et al., 1988, 1995; Magid et al., 2007; Read et al., 2003; Stewart et al., 2001), we found evidence for direct relationships between drinking to cope and specific problem domains. As hypothesized, Coping motives were directly related to Academic/Occupational problems and Risky Behaviors. A significant direct association of Coping motives that was not predicted, and thus is interpreted more tentatively, was that with Poor Self-care – an outcome found to fall higher on the continuum of alcohol problem severity identified by Kahler et al. (2005).

Taken together, the observed direct relationships depict the student drinking to cope with negative affect as one who is struggling across multiple domains – performing poorly in classes or at work, engaging in risky behaviors that may cause him or her additional problems, and failing to take proper physical care. Impairment in these domains is of significant concern. Academic performance is among the primary tasks of late adolescence; and, Nelson et al. (1996) found that role impairment predicted later progression to more severe symptoms (e.g., physiological dependence, impaired control over drinking). Moreover, many of the Self-care items fall higher on the continuum of severity empirically determined by Kahler et al. (2005). Together these findings corroborate coping motives as an important intervention target for the prevention of potentially harmful drinking outcomes. Importantly, there was evidence that some of the association between coping motives and these problem types was independent of alcohol use.

Unexpectedly, we observed a negative association between Coping motives and alcohol use. As this is at odds with at least some previous research (Cooper et al., 2000; Labouvie & Bates, 2002), suppression is one likely explanation for this finding (Maassen & Bakker, 2001). Indeed, follow-up analyses revealed that inclusion of the other motives in the model may have obscured associations between coping motives and alcohol use1.

Another possible explanation is a third variable effect of negative affect. Though depression has been linked to risk for alcohol use (c.f. Graham, Massak, Demers & Rehm, 2007), another type of negative affect – anxiety – may instead be a protective factor – especially in college populations (Buckner, Schmidt, & Meade Eggleston, 2006; Cloninger, Sigvardsson, & Bohman, 1988; O'Connor, Farrow, & Colder, 2007; Read & O'Connor, 2006; Tran, Haaga, & Chambless, 1997). The negative association between Coping motives and alcohol use could be a function of higher levels of negative affect (perhaps anxiety in particular) in those reporting drinking to cope. Similarly, this unexpected relationship might also be a function of heterogeneity of motivations within the coping motives subscale of the DMQ, which recent research suggests may benefit from modification to include subscales assessing drinking to cope with anxiety and depression separately (see Grant et al., 2007). Future research could extend our findings by examining the unique effects of depression- and anxiety-coping motives on unique alcohol problem types.

The non-hypothesized negative indirect effects of Coping motives that we observed for several problem domains are suggestive of inconsistent mediation (Davis, 1985; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000), a pattern of findings evidenced by a positive direct effect (coping motives on problem types) and negative indirect effect (via alcohol use). Taken in the context of the positive direct effects that we observed for coping motives, these negative indirect associations should not be interpreted as suggesting that coping motives are a protective factor to alcohol problems.

One hypothesized association that we did not observe was a direct effect of Coping on Dependence. As the average number of past-year dependence symptoms was relatively low with little variability (M = .53, SD = .63), restricted range could have obscured associations. Coping motives' relation with dependence may also be better observed prospectively, and perhaps later in life as alcohol involvement progresses.

The Role of Enhancement Motives

Overall, our findings regarding enhancement motives suggest that these motives are associated with alcohol problems, but that these effects occur largely via higher levels of alcohol use (Cooper et al., 1995; Magid et al., 2007). An exception was that the path suggested by modification indices from Enhancement motives to Blackouts was significant. Alcohol-induced memory loss is thought to be a function of the rate of rise in BAC, and/or “gulping” of drinks, rather than simply the amount of alcohol consumed (Perry, Argo, Barnett, Liesveld, Liskow, et al., 2006; Goodwin, Crane, & Guze, 1969; Goodwin, 1995). Perhaps enhancement drinkers, seeking alcohol's positively reinforcing effects, drink faster or in larger sips, and not simply in larger overall quantities – the result being more frequent blackouts. Though intuitively logical, findings must be replicated to bolster confidence in what now is only a speculative interpretation.

The Role of Conformity and Social Motives

With some exceptions (Cooper, 1994; Magid et al., 2007), drinking to “fit in” typically is unrelated to college alcohol use and problems (e.g., Brown & Finn, 1982; Johnston & O'Malley, 1986, Karwacki & Bradley, 1996). We also did not find conformity motives to be associated with alcohol use. We did however observe direct associations between Conformity motives and Poor self-Care, Diminished Self-Perception, and Impaired Control. These results were not hypothesized a priori based on theory or research, and thus should be interpreted with caution. Still, as two of these problem domains (self-care, impaired control) have been linked to severe and/or long-term problem use (Kahler et al., 2005; Nagoshi, 1999; O'Neill & Sher, 2000), future work should examine further conformity motives.

Though SLT might suggest the importance of social motives in the prediction of college drinking, these motives were associated with neither use nor problems in our sample. In contrast, enhancement motives were directly and indirectly associated with problem types. Of the motives related to positive reinforcement, our data support a focus on those with an internal, affective basis (enhancement). Though some evidence has supported the centrality of social reinforcement motives to alcohol involvement (Neighbors, Nichols-Anderson, Segura, & Gillaspy, 1999; Stewart, Zeitlin, & Samoluk, 1996), the data are mixed. The present study is consistent with other prior work (e.g., Read et al., 2003) showing that social reinforcement motives do not uniformly serve as a central pathway to drinking in college students.

Limitations

First among several limitations to this study is that these data were cross-sectional. Thus, it is not known whether drinking motives predict unique types of consequences over time. Results of cross-sectional analyses also may not accurately reflect longitudinal mediation effects (Maxwell & Cole, 2007); as these tests do not allow observation of the unfolding of the effect of one variable on the next. It is possible that our cross-sectional approach to mediation testing generated biased estimates of longitudinal parameters. Future research will benefit from prospective replications of our findings. Second, our sample size is relatively small. Observed effect sizes (Cohen, 1988) for significant paths ranged from small (f2 = .02 for Extraversion on Social/ Interpersonal problems) to small-medium (f2 = .09 for Enhancement on Use). Our power calculations revealed that we were powered to detect effect sizes of f2 ≥ .10. Thus, inadequate power may explain failure to observe hypothesized paths (e.g., Coping effects on Dependence).

Conclusions

The present study offers several contributions to the literature. Foremost is an examination of theorized motivational pathways to specific and validated consequence domains. The inclusion of all four drinking motives and eight problem domains in a single analysis also advances previous work. In addition, with bias-corrected bootstrap intervals, we were able to examine direct vs. indirect paths from motives to unique problem types.

The dominant pattern of direct links between coping motives and unique types of consequence that we observed has intervention implications. That is, for those who drink to cope, it may not take much alcohol to increase the likelihood of problems, making drinking itself a less important focal point. Instead, consistent with SLT, findings highlight the need for interventions to target the function underlying the drinking. Interventions also may aim to teach more effective ways for coping motivated drinkers to manage stress. Lastly, as we found the strongest support for the direct influence of coping motives on alcohol problem types, coping motivated drinkers may need to be prioritized for intervention. This study builds on previous work demonstrating associations among drinking motives and global alcohol problems, by clarifying the importance of affectively-relevant motives in contributing to some commonly experienced – and potentially meaningful – unique alcohol-related problems in the college population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21014052) to Dr. Jennifer P. Read.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb

According to Maassen & Bakker (2001), either one or a linear composite of independent variables can produce a suppressor effect. To meet the definition for negative suppression, the two (or more) independent variables first must have a positive zero-order correlation with the dependent variable and correlate positively with each other. This is the case in our sample for the four drinking motives and Alcohol Use (see Table 2). Second, negative suppression is shown when one of the independent variables receives a negative regression weight, as is the case for the association between Coping motives and Alcohol Use. This is a reflection of the fact that although the other drinking motives share relevant information with Alcohol Use, they share fewer common elements with Alcohol Use than the common elements of irrelevant information shared among the four drinking motives. To test this assumption, multiple regression analyses were conducted with alcohol use as the criterion variable. In each of three separate regression models, Coping motives were included as a predictor in combination with one of the other 4 motives. When either Social motives or Enhancement motives were included as the second predictor, the positive relationship previously observed between Coping motives and Alcohol Use changed to negative; yet, Conformity motives did not have this influence on the observed effect of Coping motives. The directional switch of the Coping motives effect also was observed when all 4 motives were included as predictors in a multiple regression model. As can be seen in Table 1, Coping motives correlated .40 with Enhancement and .44 with Social motives; the variance shared between Coping motives and these two positive reinforcement motives may account for the false appearance of a negative relationship between Coping motives and Alcohol Use. In the context of the larger model we test, MacKinnon et al. (2000) describe this pattern of findings as “inconsistent mediation,” as apparent in the opposite signs of the (positive) direct and (negative) mediated effects of Coping motives on unique problems.

References

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JR, Carman RS, Petree A. Expectations, alienation, and drinking motives among college men and women. Journal of Drug Education. 1991;21:27–33. doi: 10.2190/XWBW-YDPM-W0HA-CUYG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JR, Carman RS, Petree A. Personal and social drinking motives, family drinking history, and problems associated with drinking in two university samples. Journal of Drug Education. 1992;22:195–202. doi: 10.2190/LLQY-PFE6-484L-91L6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Finn P. Drinking to get drunk: Findings of a survey of junior and senior high school students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1982;27:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Meade Eggleston A. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. A prospective evaluation of the relationship between reasons for drinking and DSM-IV alcohol-use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998a;23:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Reasons for drinking alcohol: Relationships with DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses and alcohol consumption in a Community Sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998b;12:168–184. [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Psychophysiological Study of Emotion and Attention . The International Affective Picture System. Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida; Gainesville, FL: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the DSM-IV symptoms of impaired control over alcohol consumption in adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Childhood personality predicts alcohol abuse in young adults. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12:494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, George WH. Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:218–230. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use: A model. In: Cox WM, editor. Why People Drink. Gardner Press; New York: 1990. pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MD. The logic of causal order. In: Sullivan JL, Niemi RG, editors. Sage university paper series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A Harm Reduction Approach. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall/CRC; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW. Alcohol Amnesia. Addiction. 1995;90:315–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW, Crane JB, Guze SB. Phenomenological aspects of the alcoholic “blackout.”. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1969;115:1033–1038. doi: 10.1192/bjp.115.526.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Massak A, Demers A, Rehm J. Does the association between alcohol consumption and depression depend on how they are measured? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:78–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O'Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod P. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: A 10-year follow-up study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:659–684. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM. Why do the nation's students use drugs and alcohol? Self-reported reasons from nine national surveys. The Journal of Drug Issues. 1986;16:29–66. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2004, College Students and Adults Ages 19–45. Vol. II. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Towards efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;25:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karwacki SB, Bradley JR. Coping, drinking motives, goal attainment expectancies, and family models in relation to alcohol use among college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1996;26:243–255. doi: 10.2190/A1P0-J36H-TLMJ-0L32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E, Bates ME. Reasons for alcohol use in young adulthood: Validation of a three-dimensional measure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:145–155. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AR, Patrick CJ, Stritzke WGK. Alcohol and emotional response: A multidimensional-multilevel analysis. In: Leonard, Kenneth E, Blane, Howard T, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 1999. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maassen GH, Bakker AB. Suppressor variables in path models: Definitions and interpretations. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;30:241–270. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey KB, Bradizza CM. In: Social learning theory, in Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 2nd ed. Blane HT, Blane KE, editors. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 106–163. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Cox RH, Beck NC. Negative consequences of intercollegiate athlete drinking: The role of drinking motives. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:825–828. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole D. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus [Computer Software] Version 5 Muthén &Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT. Perceived control of drinking and other predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Addiction Research and Theory. 1999;7:291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors BD, Nichols-Anderson CL, Segura YL, Gillaspy SR. The role of drinking motivations in college students' alcohol consumption patterns. 33rd annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Nov, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Little RJA, Heath AC, Kessler RC. Patterns of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence symptom progression in a general population survey. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:449–460. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RM, Farrow SM, Colder CR. Clarifying the anxiety sensitivity and alcohol use relation: Considering alcohol expectancies as moderators. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2007;31S:587. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SE, Sher KJ. Physiological alcohol dependence symptoms in early adulthood: A longitudinal perspective. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:493–508. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry PJ, Argo TR, Barnett MJ, Liesveld JL, Liskow B, Hernan JM, Trnka MG, Brabson MA. The association of alcohol-induced blackouts and grayouts to blood alcohol concentrations. Journal of Forensic Science. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DS, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, O'Connor RM. High and low dose expectancies as mediators of personality dimensions and alcohol involvement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:1–12. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow BD, Vieth A. Personality and alcoholism: Issues, methods and etiological processes. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 54–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell M. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Humama Press, Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain-drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zeitlin SB, Samoluk SB. Examination of a three-dimensional drinking motives questionnaire in a young adult university student sample. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00036-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tran GQ, Haaga DAF, Chambless DL. Expecting that alcohol use will reduce social anxiety moderates the relation between social anxiety and alcohol consumption. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21:535–553. [Google Scholar]

- Vik P, Carrello P, Tate S, Field C. Progression of consequences among heavy-drinking college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Shiffman S. Coping and substance use: A conceptual framework. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, editors. Coping and Substance Use. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC. Coping strategies, drinking motives, and stressful life events among middle adolescents: Associations with emotional and behavioral problems and with academic functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:551–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]