Abstract

The concept of a critical period for visual development early in life during which sensory experience is essential to normal neural development is now well established. However recent evidence suggests that a limited degree of plasticity remains after this period and well into adulthood. Here, we ask the question, "what limits the degree of plasticity in adulthood?" Although this limit has been assumed to be due to neural factors, we show that the optical quality of the retinal image ultimately limits the brain potential for change. We correct the high-order aberrations (HOAs) normally present in the eye's optics using adaptive optics, and reveal a greater degree of neuronal plasticity than previously appreciated.

The pioneering work of Hubel and Wiesel1 established the concept of a critical period for visual development early in life during which sensory experience is essential to normal neural development. Although this is a fundamental concept in neurobiology it is also now recognized that some limited plasticity remains after this period well into adulthood2,3,4,5. During recent decades, numerous studies have shown that a range of visual functions in normal adult subjects can be improved as a result of intensive training (termed perceptual learning). These functions include contrast sensitivity6,7,8,9,10, motion perception11,12,13 and object recognition14,15. However, there is abundant evidence to indicate that this kind of learning-induced plasticity in adults while being possible is also very limited in extent8,9,16,17,18. We wished to know what limits visual improvements that can occur as a consequence of perceptual learning in the normal adult. This refers directly to the mechanisms of brain plasticity that operate beyond the critical period.

In the adult visual system, uncorrectable optical aberrations limit the quality of the retinal image19,20, even when defocus is corrected by sphero-cylindrical lenses21,22,23. These aberrations, termed higher order aberrations (HOAs)19, exist throughout the life span24,25,26,27. We wondered if HOAs set a fundamental limit to the benefits obtained from perceptual learning for the adult visual system.

The aim of the current study is to assess whether perceptual learning in normal adults is limited by the eye's optical quality. To address this we measure the effects of perceptual learning on visual sensitivity with and without HOAs-correction, using a real-time closed-loop adaptive optics visual stimulator system28 (for details, see Supplementary online). We found larger and more robust contrast sensitivity improvements when the HOAs were corrected than when they were left uncorrected. We show that this is not due to the better optical quality per se or by the brain's ability to utilize this information but a consequence of improved perceptual learning using images of higher optical quality. This also transferred to a significant improvement of visual acuity in the HOAs-corrected perceptual learning group, compared with that of the HOAs-uncorrected group. We confirm previous reports of brain plasticity well beyond the critical period and show that its benefits are even larger if the eye's higher-order optical aberrations are corrected.

Results

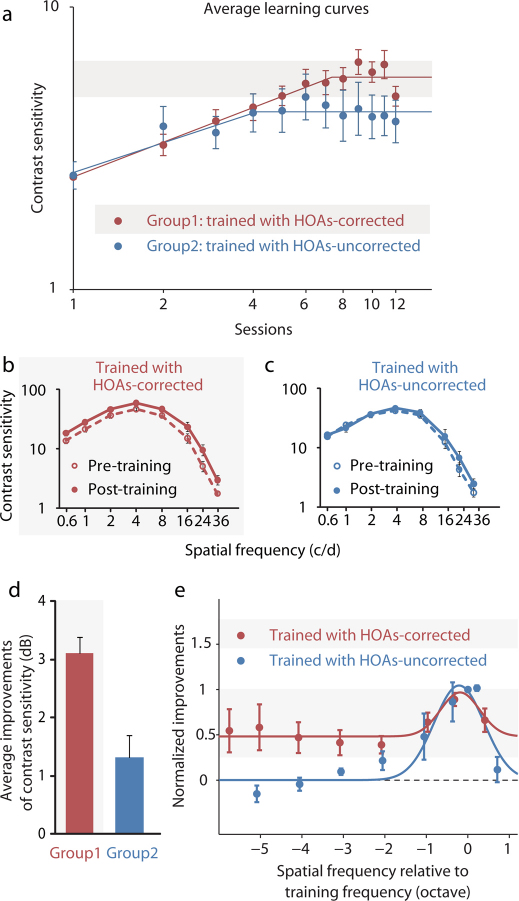

Visually normal adults were separated into two training groups, in one (Group1 – 13 subjects) training was undertaken under the HOAs-corrected condition whereas in the other (Group2 – 8 subjects) training was undertaken under normal viewing condition (i.e. HOAs-uncorrected). Learning effects were then analyzed in accordance with individuals' pre-training baseline conditions. In both cases, 10 training sessions of 1hour were undertaken with a high spatial frequency stimulus. For each subject, a high spatial frequency was selected for training that corresponded to a pre-training contrast threshold of 0.4. In particular, subjects in Group1 were trained using spatial frequency when contrast threshold at HOAs-corrected condition is 0.4; subjects in Group2 were trained using spatial frequency when contrast threshold at HOAs-uncorrected condition is 0.4. Correction of HOAs has been shown to improve contrast sensitivity at all spatial frequencies but more so at higher spatial frequencies29,30. The contrast sensitivity benefits that we found when the HOAs were corrected were similar to that previously reported by Yoon and Williams30 for a 3mm pupil (see Supplementary Table S1 online). After training, Group1, the HOAs-corrected group, showed a 5.39 dB (86.1%) significant (Paired Samples Test, t(12) = –7.66, P = 0.0000059, 2-tailed) improvement of contrast sensitivity. The slope of the average learning curve was 0.41 log units, and reached a plateau after 7.35 training sessions (Fig. 1a). Group2, the HOAs-uncorrected group, showed a smaller (3.42 dB or 48.2%) but also significant (Paired Samples Test, t(7) = –2.62, P = 0.03, 2-tailed) improvement. The slope of the average learning curve was 0.35 log unit, and reached a plateau after 4.12 training sessions (Fig. 1a- individual leaning curves data are given in Supplementary Table S2 online).

Figure 1. Different training effects between Group1 and Group2.

(a) Average learning curves of Group1 (red) and Group2 (blue). The first and last points in each condition were derived from pre- and post-training contrast sensitivity function (CSF) measurements, respectively. Error bars, SEM. Subjects in Group1 were trained under the HOAs-corrected condition. Red solid line represents a piecewise linear model fit to the average learning curve of Group1; Subjects in Group2 were trained under the HOAs-uncorrected condition. Blue solid line represents a piecewise linear model fit to the average learning curve of Group2. (b) Average post- and pre-training CSFs of Group1. (c) Average post- and pre-training CSFs of Group2. (d) Average magnitude of contrast sensitivity improvements across observers and spatial frequencies in Group1 (3.11 dB) and Group2 (1.31 dB); (e) Average normalized improvement curves of Group1 (red) and Group2 (blue). Dashed line represents no improvement. Solid lines represent Gaussian fit to the average normalized improvement curves.

Contrast sensitivity functions (CSFs), which measure sensitivity to stimuli of different spatial frequencies, were measured at pre- and post-training stages for both groups. There were significant improvements after training in both Group1 (Fig. 1b, post- vs. pre-training: F (1, 12) = 75.43, P<0.00001) and Group2 (Fig. 1c, post- vs. pre-training: F (1, 7) = 5.46, P = 0.05). The average magnitude of the contrast sensitivity improvements across observers and spatial frequencies were 3.11 dB and 1.31 dB in Group1 and Group2, respectively (Fig. 1d). For the subjects in Group1 and Group2 who showed significant contrast sensitivity improvement (all 13 subjects in Group1 and only 4 subjects in Group2. For method, see Supplementary online), while the magnitude of improvements at the training spatial frequency were not significantly different (Independent Samples Test, t(15) = –0.58, P = 0.57, 2-tailed), a different spatial frequency dependency was evident (Fig. 1e). A Gaussian function was fitted to the average normalized improvement curve6 (for detail, see Supplementary online): there was a specific learning effect (full width at half height bandwidth of 1.11 octaves) together with a more general increase in sensitivity at all spatial frequencies tested in Group1. The magnitude of this general increase was half the magnitude of the peak increase; while only a specific learning effect (bandwidth 1.42octaves) in Group2.

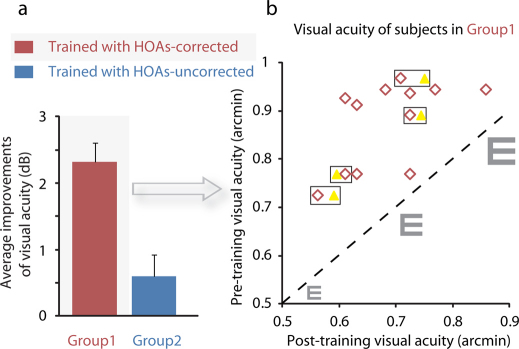

Another important finding was that training also significantly improved visual acuity in Group1 (Paired Samples Test, t(12) = 9.16, P = 0.00000091, 2-tailed), but not in Group2 (Paired Samples Test, t(7) = 1.42, P = 0.20, 2-tailed). The average improvement of visual acuity in Group1 was 2.32 dB (or 31%), and this was larger than what was found in Group2 (Independent Samples Test, t(19) = 3.97, P = 0.00082, 2-tailed) (Fig. 2a). All subjects in Group1 had visual acuity improvements after training (Fig. 2b) that could sustain for at least 5 months (4 subjects in Group1 had visual acuity retested 5 months after training).

Figure 2. Improvements of visual acuity after training in Group1 (red) and Group2 (blue).

Visual acuity associated with 75% correct identification was measured with the Chinese Tumbling E Chart at HOAs-uncorrected condition, and converted to MAR acuity. (a) There were significant improvements of visual acuity in Group1 (Paired Samples Test, t(12) = 9.16, P = 0.00000091, 2-tailed), but not in Group2 (Paired Samples Test, t(7) = 1.42, P = 0.20, 2-tailed). (b) Visual acuity of all subjects before and after training in Group1. Abscissa represents visual acuity after training; ordinate represents visual acuity before training. Each red '◊' point represents one subject. The dashed line indicates a prediction of no improvement. The 4 yellow ' ' points represent visual acuity retested 5 months after training for 4 subjects (the corresponding pre-/post-training results of these 4 subjects are shown by red '◊' points that are marked by black '□').

' points represent visual acuity retested 5 months after training for 4 subjects (the corresponding pre-/post-training results of these 4 subjects are shown by red '◊' points that are marked by black '□').

It is important to stress that correction of HOAs results in improved optical quality and therefore improved contrast sensitivity and visual acuity, however these purely optical improvements are incorporated in the pre-training baseline measurements from which any training improvements are assessed. To confirm that the CSF improvements we found after training were neural in origin, we also assessed pre- and post-training optical modulation transfer functions (MTF), to quantify the quality of the optics20, for subjects in Group1 and Group2. We found significant improvements in the MTFs as a result of the correction of HOAs but no significant change in the MTFs after training for both groups. On the other hand, the neural transfer function (NTF), calculated from subtracting MTF from the CSF31, showed significant improvements after training in both groups (for details, see Supplementary online). These results demonstrate that optical quality did not alter significantly as a result of training; the training-based improvement to the CSF reflected neural changes.

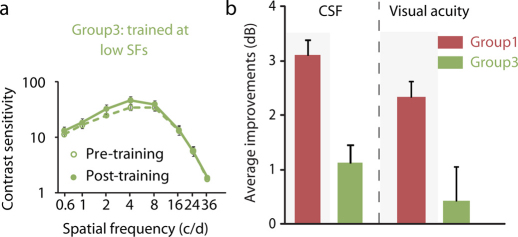

To confirm that the neural benefits were contingent on perceptual learning and not just a passive consequence of having a sharper retinal image, we undertook another training experiment under the HOAs-corrected condition (Group3, 6 adults) using a spatial frequency which, while being optimal in terms of HOAs-corrected sensitivity, was sub-optimal in terms of perceptual training9. Group3 was same as Group1, except subjects were trained at a spatial frequency that corresponded to the peak of the CSF, a frequency lower than previously used (Figs 1 & 2) and one known to be non-optimal in terms of perceptual learning9. If the previous improvements were simply a passive adaptation32 to the new HOAs-corrected image, (and not specifically a result of perceptual learning) we would expect to find similar results for Group3 as we did previously for Group1. Interestingly, we found much less improvement in Group3 (Fig. 3): the average magnitude of improvements across observers and spatial frequencies was 1.12 dB, which was much less than previously found in Group1 (F(1,17) = 9.86, P = 0.006); improvements were not generalized across spatial frequency and did not transfer to letter acuity (Paired Samples Test, t(5) = 0.32, P = 0.76, 2-tailed). In these respects they were different to that previously found in Group1 for the high spatial frequency training target, suggesting that a HOAs-corrected environment in itself is necessary but not sufficient to explain the results previously described for Group1 of this study; training at a near-cutoff spatial frequency is also required, which suggests the neural improvement is specific to perceptual training.

Figure 3. Training effect in Group3.

Subjects in Group3 were trained at a low spatial frequency (spatial frequency that has peak contrast sensitivity under the HOAs-corrected condition), when HOAs were corrected. Error bars, SEM. (a) Average post- and pre-training CSFs of Group3; (b) Average magnitude of improvements across observers and spatial frequencies in Group3 was 1.12 dB, less than in Group1 (F(1,17) = 9.86, P = 0.006); improvements of visual acuity in Group3 were not significant (Paired Samples Test, t(5) = 0.32, P = 0.76, 2-tailed), and less than in Group1 (Independent Samples Test, t(17) = 3.27, P = 0.004, 2-tailed).

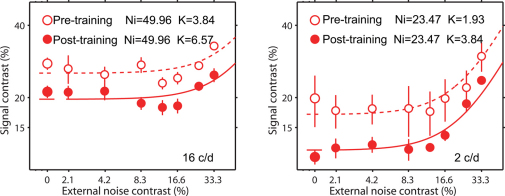

The neural improvements in contrast sensitivity after training under the HOAs-corrected condition could in principle be due to increased signal efficiency or reduced internal noise. Either effect would result in improved signal-to-noise and thus, lower thresholds33,34,35,36. To separate between these two potential explanations, we assessed the training improvement in contrast thresholds for stimuli with and without added spatial noise. Training improvements were measured at a spatial frequency of 16c/d and 2c/d for 4 subjects in Group1 within the HOAs-corrected environment. These results are shown in Fig. 4 where contrast thresholds are plotted against the amplitude of the added white spatial noise, before and after training in the HOAs-corrected environment. The solid lines are best fits to an equivalent noise model of the form:

Where K is related to sampling efficiency, E is the squared contrast energy, N is the squared rms noise contrast, and Ni is related to the internal noise required to account for the measured thresholds. This is referred to as the equivalent noise model33,34,37. The values of the two derived parameters (K and Ni) are shown in Fig. 4. We found that contrast sensitivity improvements under the HOAs-corrected condition for noise-free stimuli were similar to those found with noisy stimuli (Fig. 4), indicating an improved neural efficiency (K) as a consequence of training in the HOAs-corrected condition training38, not a reduction in the internal neural noise (Ni).

Figure 4. Averaged sensitivity (squared contrast) of four subjects in Group1 (trained with HOAs-corrected) as functions of external noise levels (squared rms) for spatial frequencies of 16c/d and 2c/d.

Contrast thresholds corresponded to 79.3% correct ' ', pre-training; '

', pre-training; ' ', post-training; Error bars, SEM. Solid lines are curve fits to the equivalent noise (see text) and demonstrate that perceptual training improvements are the result of improved neural efficiency rather than diminished neural internal noise.

', post-training; Error bars, SEM. Solid lines are curve fits to the equivalent noise (see text) and demonstrate that perceptual training improvements are the result of improved neural efficiency rather than diminished neural internal noise.

Discussion

We demonstrate that the optical quality of the eye limits visual improvements from perceptual learning in adults well beyond the critical period. This in turn means that a greater degree of adult plasticity exists than previously thought. When the HOAs are corrected, we show larger visual improvements that are a consequence of perceptual learning, not the better viewing condition per se. Using the conventional method where training occurred in a HOAs-uncorrected environment (Group2), we found only half of the subjects exhibited improvement in contrast sensitivity, and the average bandwidth of the improvement from perceptual learning was 1.42 octaves. These results are consistent with previous results in the literature. For example, Huang et al.9 found only 7 out of 14 normal adults had performance improvement, and the average bandwidth was 1.40 octaves.

Interestingly, we found that identical training within the HOAs-corrected environment (Group1) produced very different results: all subjects exhibited visual performance improvement; training not only produced the expected specific improvement9 but also produced a general benefit for all spatial frequencies tested. General benefits after training have been reported previously. Sowden et al.6 reported that training subjects at a parafovea site resulted in an improvement with a bandwidth of 1.30 octaves and a general learning effect of 0.05 log units. They claimed that the general learning effect was due to using naive subjects who were not pre-trained. However, in our study, the general learning effect is not amenable to this explanation. First of all, all the subjects in our study received 1.5h of practice to make sure that they were familiar with the task requirements before the experiment commenced. Second, because Group1 and Group2 were measured using an identical procedure, the explanation for the general improvement displayed by Group1 cannot be in terms of any general procedural learning effect. It must be the consequence of learning within a HOAs-corrected environment, as this is the only difference in the experimental manipulations between Group1 and Group2.

The general improvement we report at all spatial frequencies was only found in the HOAs-corrected group (Group1). It is not caused by the improved quality of the retinal image per se because this improvement, which is shown in Supplementary Table S3 online, is instantaneous39, easily verified by the improved MTFs and factored out since it is incorporated in our pre-training baseline. Furthermore it cannot be the results of slow term optical changes over the duration of training because it was not reflected in the optical transfer functions we obtained (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online). Therefore the improvement that occurred over the training period must be neural in origin. This neural effect is not a passive consequence of extended viewing under the HOAs-corrected condition32 but rather a consequence of perceptual learning per se under the HOAs-corrected condition. The hallmarks of perceptual learning9,10 are its magnitude39, its generalization to lower spatial frequencies and its transfer to letter acuity. These three conditions are met only when perceptual training is undertaken at a high spatial frequency (Group1) not at a peak spatial frequency (Group3). Passive neural adaptation cannot provide an explanation because 1. No similar effects were seen for Group3 who had similar HOAs-corrected experience, 2. For each subject, exposure to the HOAs-corrected condition was lasting only 1hr a day with at least 15hrs of normal viewing and 3. The improvements were sustained in that visual acuity improvements under normal viewing condition were still present 5 months later. Therefore, we are left to conclude that the visual improvement (i.e. contrast sensitivity and letter acuity) exhibited by Group1 are a consequence of perceptual training when undertaken under the HOAs-corrected viewing condition.

We also show that the neural improvements reported here are due to improved transduction efficiencies rather than reductions in internal neural noise. Using an equivalent noise model36 to separate these different components of perceptual learning, we show, by evaluating the effects of additive spatial noise, that the benefits are multiplicative rather than additive in nature, consistent with the notion of improved signaling efficiency. This is in agreement with a number of studies that have investigated this distinction for other perceptual learning tasks, such as position discrimination40,41, letter identification42, faces and textures38 and contrast detection8. The general finding is that training improves efficiency (position discrimination, letter identification, faces & textures) but that there are also, in some cases, reductions in internal noise (contrast detection). Thus the mechanisms underlying the effects we report may not be different in principle to those reposted by others; simply our effects are larger due to the improved optical quality of our participants. Parenthetically, the fact that the improvements are due to efficiency (or sampling efficiency), rules out a purely optical explanation, as this would have been manifested as a reduction in the equivalent noise measure36,43.

It has been argued that the typical perceptual learning that exhibits a selectivity for spatial frequency, contrast and field position is more to do with changes in the higher-level decision stage than it is to do with improved efficiency of neural responses at lower level of visual processing44. The improvements we report using adaptive optics and trained at a high spatial frequency involve two components, one is the typical leaning effect that is spatial frequency specific and does not transfer to other functions such as letter acuity8,9 whereas the other extends to lower spatial frequencies and represents not only a more generalized improvement at all spatial frequencies but a more generalized improvement in visual function in general, extending to letter acuity (Fig. 2). This latter component is due to perceptual learning because it is not present when training is undertaken at a low spatial frequency even when the HOAs have been corrected ( i.e. Group3). It is possible that the sites of these two components are different and that the more generalized benefit occurs at an earlier site of processing.

Visual function rapidly improves after birth reaching asymptotic values for acuity and contrast sensitivity by 9 months of age. While it is true that infants do suffer from refractive errors in early life45,46,47, there is good evidence48,49 that their depth of field, due to their relatively large pupils, is sufficiently large to make them resistant to the HOAs that limit adult vision. We surmise that initial neural development reaches asymptotic levels that are eventually matched to and limited by the optical quality of the adult eye. Improvements in the eye's optical quality during adulthood by adaptive optics can facilitate concurrent gains in the efficiency of neural learning in visual areas of the brain. We reveal two components to this plasticity, one tuned for spatial frequency and limited to high spatial frequencies and another one that is untuned for spatial frequency. This latter component is only revealed when the optical quality is improved and a high spatial frequency stimulus is used to engage perceptual learning. Importantly, this second component allows benefits to extend to the detection of stimuli that are more spatially broadband such as letters. In turn this implies the visual benefit will transfer to the detection of real world objects. Our finding in normals with improved optics may help explain one of the mysteries of perceptual learning in amblypes where, unlike normals, the visual benefits do transfer from the trained spatial frequency to letters50. In amblyopes, the optics do not limit function due to the presence of neural loss and to this extent amblyopes are like normal subjects whose HOAs have been corrected and for which more generalized spatial frequency improvements are obtainable. Our finding of enhanced visual plasticity in the adult, in both magnitude at the trained spatial frequency and extent of transfer to other spatial frequencies, is directly relevant to the development of new therapies applied in later life to redress brain dysfunction resulting from anomalous visual development earlier in life9,10,51,52.

Methods

Observers

Twenty seven adults (Age: 19–26) with normal or corrected to normal vision (slightly myopic,  ) were randomly assigned into three groups. There was no substantial difference between these groups in terms of mean age or mean refractive error. There were 13 observers, 8 observers and 6 observers in Group1, Group2 and Group3 respectively. Group1 was trained at the HOAs-corrected cut-off spatial frequency (spatial frequency when contrast threshold at HOAs-corrected condition is 0.4 which was 29.53 ± 1.68c/d (s.e.m.)), with HOAs corrected. Group2 was trained at the HOAs-uncorrected cut-off spatial frequency (spatial frequency when contrast threshold at HOAs-uncorrected condition is 0.4 which was 28.75 ± 1.88c/d (s.e.m.)), with HOAs uncorrected. Group3 was the same as Group1, except subjects were trained at a lower spatial frequency (spatial frequency corresponding to peak contrast sensitivity at HOAs-corrected condition which was 6.00 ± 0.89c/d (s.e.m.)).

) were randomly assigned into three groups. There was no substantial difference between these groups in terms of mean age or mean refractive error. There were 13 observers, 8 observers and 6 observers in Group1, Group2 and Group3 respectively. Group1 was trained at the HOAs-corrected cut-off spatial frequency (spatial frequency when contrast threshold at HOAs-corrected condition is 0.4 which was 29.53 ± 1.68c/d (s.e.m.)), with HOAs corrected. Group2 was trained at the HOAs-uncorrected cut-off spatial frequency (spatial frequency when contrast threshold at HOAs-uncorrected condition is 0.4 which was 28.75 ± 1.88c/d (s.e.m.)), with HOAs uncorrected. Group3 was the same as Group1, except subjects were trained at a lower spatial frequency (spatial frequency corresponding to peak contrast sensitivity at HOAs-corrected condition which was 6.00 ± 0.89c/d (s.e.m.)).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Science and Technology of China. All subjects were naive to the purpose of the experiment and informed consent was obtained from each of them.

Apparatus

All experiments were conducted on a real-time closed-loop adaptive optics visual stimulator system (AOVS)28 in a dark room. It consists of a Hartmann-Shack wavefront sensor (WFS) with 97 lenslets, operating at 25Hz, and a 37-actuator PZT deformable mirror with a stroke of about 2 microns. The control bandwidth of the system is about 1Hz. See Supplementary online for diagram (Fig. S1) and more detail. The aberrations are measured for a 4mm artificial pupil up to 35 Zernike polynomials (7th order) according to OSA wavefront standards19.

Design

The experiment in each group consisted of four consecutive stages: a pre-training practice stage, a pre-training test stage, a training stage and a post-training test stage. For each subject, only one eye was used in the experiment, the other eye was covered by an opaque fabric. The tested eye having normal or corrected to normal vision was selected randomly for each observer. At the pre- and post-training test stages, visual acuity was measured under conditions where the higher order aberrations (HOAs) were uncorrected. Contrast sensitivity functions (CSFs) were measured under both the HOAs- corrected and uncorrected conditions. Visual acuity corresponding to 75% correct identification was measured with the Chinese Tumbling E Chart, and converted to MAR acuity. Contrast sensitivity, defined as the reciprocal of contrast threshold for detecting a sine-wave grating with 79.3% accuracy, was measured at spatial frequencies 0.6, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 36c/deg on the AOVS. See Supplementary online for more detail.

Procedure

A two-interval forced-choice procedure was used for both training and threshold measurements. In training and CSF measurements, the presentation sequence in each trial was as follows: a 267-ms fixation cross signalled by a brief tone in the beginning, a 117-ms interval, a 500-ms inter-stimulus interval blank, a 267-ms fixation signalled by a brief tone in the beginning, a 117-ms second interval, and blank until response. See Supplementary online for more detail.

Author Contributions

J.-W.Z., Y.-D.Z., R.-F.H. and Y.-F.Z. conceived the experiments. J.-W.Z., Y.D., H.-X.Z, R.L., F.H. and B.L. performed the experiments. J.-W.Z., Y.D., H.-X.Z. and R.-F.H. analyzed the data. J.-W.Z., Y.-D.Z., R.-F.H. and Y.-F.Z. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. J.-W.Z. and Y.-D.Z. are co-first authors of this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Programs, 2011CBA00405 and 2009CB941303), National Science Foundation of China (NSFC 30630027 to YZ and 60808031 to YD), Frontier Research Foundation of Institute of Optics and Electronics: C09K006 (YD), and the CIHR (# MT108-18) to RFH.

Footnotes

There is NO Competing Interest. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Hubel D. H. & Wiesel T. N. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J Physiol 206, 419–436 (1970). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone R. L. Perceptual learning. Annu Rev Psychol 49, 585–612 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C. D., Sigman M. & Crist R. E. The neural basis of perceptual learning. Neuron 31, 681–697 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y., Nanez J. E. & Watanabe T. Advances in visual perceptual learning and plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 11, 53–60 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. L., Hua T., Huang C. B., Zhou Y. & Dosher B. A. Visual perceptual learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowden P. T., Rose D. & Davies I. R. L. Perceptual learning of luminance contrast detection: specific for spatial frequency and retinal location but not orientation. Vision Research 42, 1249–1258 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua T. et al.. Perceptual learning improves contrast sensitivity of V1 neurons in cats. Curr Biol 20, 887–894 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. B., Lu Z. L. & Zhou Y. Mechanisms underlying perceptual learning of contrast detection in adults with anisometropic amblyopia. J Vis 9, 24 21–14 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. B., Zhou Y. & Lu Z. L. Broad bandwidth of perceptual learning in the visual system of adults with anisometropic amblyopia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 4068–4073 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al.. Perceptual learning improves contrast sensitivity and visual acuity in adults with anisometropic amblyopia. Vision Research 46, 739–750 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. L. Perceptual learning in motion discrimination that generalizes across motion directions. P Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 14085–14087 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K. & Sekuler R. A specific and enduring improvement in visual motion discrimination. Science 218, 697–698 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart L., Battelli L., Walsh V. & Cowey A. Motion perception and perceptual learning studied by magnetic stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl 51, 334–350 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmanski C. S. & Engel S. A. Perceptual learning in object recognition: object specificity and size invariance. Vision Res 40, 473–484 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golcu D. & Gilbert C. D. Perceptual learning of object shape. J Neurosci 29, 13621–13629 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini A. & Berardi N. Perceptual-Learning Specific for Orientation and Spatial-Frequency. Nature 287, 43–44 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar M. & Hochstein S. Task difficulty and the specificity of perceptual learning. Nature 387, 401–406 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahle M. Perceptual learning: specificity versus generalization. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15, 154–160 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibos L. N., Applegate R. A., Schwiegerling J. T., Webb R. & Taskforce V. S. in Vision Science and its Applications (VSIA) (Santa Fe, New Mexico., 2000).

- Williams D. R. et al.. (eds Krueger R., Applegate A.& Macrae S. M.) 19–38 (Slack, 2004).

- Smirnov M. S. Measurement of the wave aberration of the human eye. Biofizika 6, 776–795 (1961). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland B. & Howland H. C. Subjective measurement of high-order aberrations of the eye. Science 193, 580–582 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. Z., Grimm B., Goelz S. & Bille J. F. Objective Measurement of Wave Aberrations of the Human Eye with the Use of a Hartmann-Shack Wave-Front Sensor. Journal of the Optical Society of America a-Optics Image Science and Vision 11, 1949–1957 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette I., Bueno J. M., Parent M., Hamam H. & Simonet P. Monochromatic aberrations as a function of age, from childhood to advanced age. Invest Ophth Vis Sci 44, 5438–5446 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J., Guirao A., Cox I. G. & Williams D. R. Monochromatic aberrations of the human eye in a large population. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 18, 1793–1803 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan J. S., Marcos S. & Burns S. A. Age-related changes in monochromatic wave aberrations of the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42, 1390–1395 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan C., O'Keefe M. & Soeldner H. Higher-order aberrations in children. American Journal of Ophthalmology 141, 67–70 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. et al.. Effects of Monochromatic Aberration on Visual Acuity Using Adaptive Optics. Optometry and Vision Science 86, 1–7 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. et al.. Visual benefit of correcting higher order aberrations of the eye. J Refract Surg 16, S554–559 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon G. Y. & Williams D. R. Visual performance after correcting the monochromatic and chromatic aberrations of the eye. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 19, 266–275 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F. W. Probing the Human Visual-System - a Citation-Classic Commentary on Optical and Retinal Factors Affecting Visual Resolution by Campbell, F.W., and Green, D.G. Cc/Life Sci 16–16 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Yehezkel O., Sagi D., Sterkin A., Belkin M. & Polat U. Learning to adapt: Dynamics of readaptation to geometrical distortions. Vision Res 50, 1550–1558 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A. E., Wagner R. F., Jennings R. J. & Barlow H. B. Efficiency of human visual signal discrimination. Science 214, 93–94 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli D. Effects of visual noise. (University of Cambridge, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Barlow H. Retinal and central factors in human vision limited by noise. Vertebrate photoreception, 337¨C358 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Kersten D., Hess R. & Plant G. Assessing contrast sensitivity behind cloudy media. Clinical Vision Science 2, 143¨C158 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Legge G. & Rubin G. Contrast sensitivity function as a screening test: a critique. American journal of optometry and physiological optics 63, 265 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold J., Bennett P. J. & Sekuler A. B. Signal but not noise changes with perceptual learning. Nature 402, 176–178 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi E. A. & Roorda A. Is visual resolution after adaptive optics correction susceptible to perceptual learning? J Vis 10, 11 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. W. & Levi D. M. Characterizing the mechanisms of improvement for position discrimination in adult amblyopia. J Vis 4, 476–487 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. W., Klein S. A. & Levi D. M. Prolonged perceptual learning of positional acuity in adult amblyopia: perceptual template retuning dynamics. J Neurosci 28, 14223–14229 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. T., Levi D. M. & Tjan B. S. Learning letter identification in peripheral vision. Vision Res 45, 1399–1412 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legge G. E., Kersten D. & Burgess A. E. Contrast discrimination in noise. J Opt Soc Am A 4, 391–404 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Klein S. A. & Levi D. M. Perceptual learning in contrast discrimination and the (minimal) role of context. Journal of Vision 4 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson J. & French J. Astigmatism and orientation preference in human infants. Vision Res 19, 1315–1317 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda J., Scheiman M., Mohindra I. & Held R. Astigmatism in children: changes in axis and amount from birth to six years. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 25, 88–92 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda J., Thorn F., Bauer J. & Held R. Emmetropization and the Progression of Manifest Refraction in Children Followed from Infancy to Puberty. Clin Vision Sci 8, 337–344 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Green D. G., Powers M. K. & Banks M. S. Depth of focus, eye size and visual acuity. Vision Res 20, 827–835 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M. K. & Dobson V. Effect of focus on visual acuity of human infants. Vision Res 22, 521–528 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astle A. T., Webb B. S. & McGraw P. V. The pattern of learned visual improvements in adult amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 7195–7204 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B., Mansouri B., Koski L. & Hess R. F. Brain plasticity in the adult: modulation of function in amblyopia with rTMS. Curr Biol 18, 1067–1071 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polat U., Ma-Naim T., Belkin M. & Sagi D. Improving vision in adult amblyopia by perceptual learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 6692–6697 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary