Abstract

Aim:

To compare the efficacy of low- versus medium-pressure shunts in pediatric hydrocephalus in a randomized controlled trial.

Materials and Methods:

Forty patients of pediatric hydrocephalus were randomized into two groups. The Chhabra differential pressure VP shunt (low or medium) was inserted in every patient. Postoperative follow-up was performed for symptomatic improvement and radiological evaluation (by sonography or computed tomography scan) for ventricle hemispheric ratio (VHR). Comparative analysis of pre- and postoperative VHR and need of redo surgery for shunt malformation were carried out to establish outcomes.

Results:

Nineteen patients had a low-pressure and 21 patients had a medium-pressure shunt inserted. The age of the patients ranged from 1 day to 10 years. The average preoperative VHR in group A was 55.37%, which reduced to 40% postoperatively (P = 0.00005); likewise, the pre- and postoperative VHR in group B were 61.57% and 42%, respectively, which was statistically significant (P = 0.0006). The complications of shunts and incidence of redo shunt surgery in both groups were not found to be statistically significant (P = 0.5614).

Conclusions:

The study found no significant difference in the outcome of patients with low- or medium-pressure shunt placement in pediatric hydrocephalus.

KEY WORDS: Hydrocephalus, shunt device pressures, ventriculoperitoneal shunt

INTRODUCTION

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are the mainstay of treatment in hydrocephalus, especially in neonates and infants.[1,2] The standard valves simply work depending on the differential pressure across them, which is termed as the opening pressure. Typically, there are low (0–5 cm of H2O), medium (5–10 cm of H2O) and high pressure (10–15 cm of H2O) shunts for which there are no universal standards. Once open, these valves provide very little resistance to flow. Drake et al. in a large-scale randomized trial compared standard differential valves to externally programmable valves and found that the new design did not significantly affect the shunt failure rates.[3,4]

Selection of working pressure of shunts has been a matter of controversy for the last 30 years. There are no well-defined indications for the selection of shunts and its outcome. Not many studies done on this issue and the few studies that have been done have given equivocal results.[5,6] We believe that this is the first randomized controlled trial comparing the outcome of low- versus medium-pressure shunts in pediatric hydrocephalus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 40 patients of pediatric hydrocephalus were studied prospectively from October 2005 to April 2009. In all children, the Chhabra VP shunt, either low or medium pressure (G. Surgiwear Ltd., Uttar Pradesh, India) was used. VP shunt was placed according to the routinely established procedure through the parietal approach. The patients with hydrocephalus were randomized to receive low- or medium-pressure VP shunts and were categorized into two groups (group A – 19 and group B – 21 patients).

Randomization was done by a third person (randomizer) who was not part of the study and, thus, participant, investigator and analyzer were all unaware of group distribution, establishing a triple-blind study. The patients were then followed-up postoperatively monthly for the first 3 months and then 3–6-monthly thereafter. The assessment was done for symptomatic improvement. Radiological evaluation of the ventricular size was done by measuring ventricle–hemispheric ratio (VHR) pre- and postoperatively (at 3 months). The VHR (normal: 24–33%) was calculated from the computed tomography (CT) scan films or on ultrasonography by calculating the ratio of the maximum ventricular diameter of the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle at the level of the atrium to the diameter of the brain at the same level. The patients were also assessed for complications of the shunt procedure, like malfunctions, infections and seizures. At the end of the study, the randomizer was asked to reveal the groups allotted and the results were compiled.

RESULTS

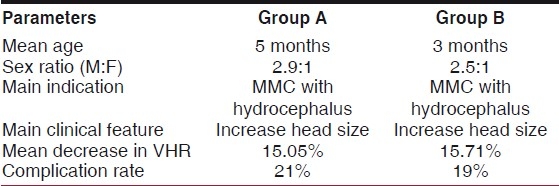

Nineteen cases in group A had low-pressure shunt, and the medium-pressure shunts were inserted in 21 patients of group B. The median age of group A was 5 months (0–36 years) and of group B was 3 months (0–120 years). Infants (82.5%) dominated the study; the eldest patient in our study was of 10 years and the youngest was of 1 day. Indications for shunt surgery were hydrocephalus associated with meningomyelocele (70%), congenital hydrocephalus (20%) and others (10%). The patients with meningomyelocele underwent a meningomyelocele repair at the time of presentation. A VP shunt was placed later when these patients developed increasing head size and VHR (except for one child who presented with frank hydrocephalus with severe hind brain dysfunction and underwent both surgeries simultaneously). Mostly male patients were present in both groups (group A 14/19 versus group B 15/21). The increased head size (67.5%) was the common clinical feature, followed by signs of meningitis, raised intracranial pressure and other neurological signs. The mean follow-up was 23 months (ranging from 12 to 42 months) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparative results of both groups

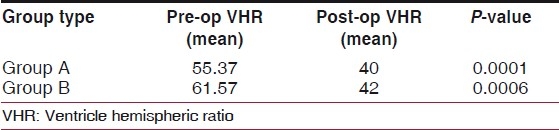

The average preoperative VHR in the low-pressure group was 55.37%, which reduced to 40% postoperatively, considered to be extremely statistically significant (P = 0.0001) [Table 1]. Likewise, pre- and postoperative VHR in group B were 61.57% vs. 42% (P = 0.0006) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pre- and postoperative ventricle hemispheric ratio

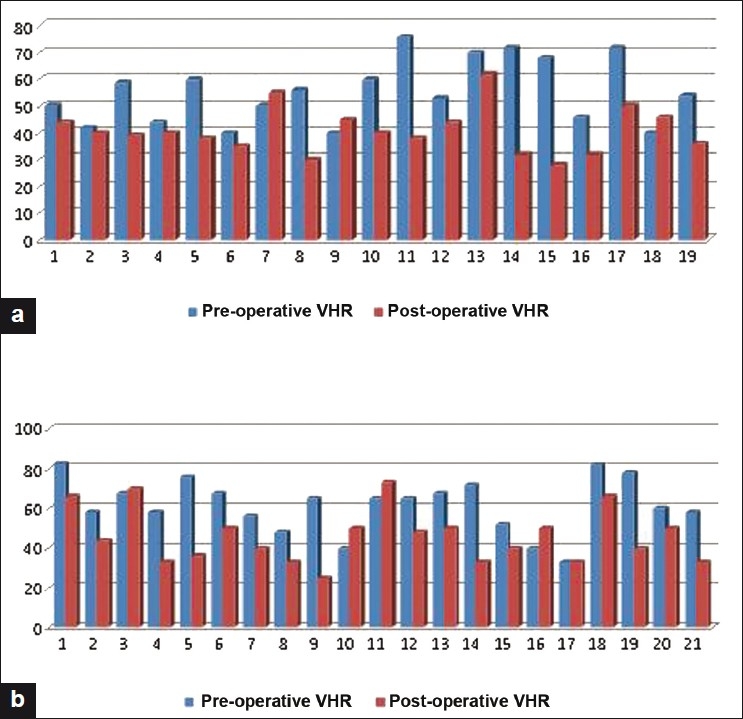

The mean decrease in VHR in Group A was 15.05% while in Group B it was 15.71%; this difference is considered to be not statistically significant (P = 0.8907). The change in VHR is depicted in Figure 1. There was no incidence of slit ventricle syndrome in either group. On follow-up, four patients had shunt blockages (10%), two in each group, with three patients having associated shunt infections (two patients from the low-pressure group and one patient from the medium-pressure group). One patient in the medium-pressure group developed shunt breakage. Five patients required redo shunt procedure due to these complications (three patients in the low-pressure group and two patients in the medium-pressure group) (P = 0.5614).

Figure 1.

Pre- and postoperative ventricle hemispheric ratio in groups a and b

DISCUSSION

Comparison of outcomes of low- and medium-pressure shunts have been done by Boon et al. in adults with normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) and in adult-onset obstructive hydrocephalus by McQuarrie et al., who concluded that low-pressure shunts were followed by better (70%) objective improvement in all the cases than medium-pressure shunts,[5,7,8] while Larsson et al. in their study concluded that clinical effect and reduction in ventricular size are independent of shunt opening pressure.[9] Very few studies have been conducted calculating the VHR of children with hydrocephalus.[1]

Recent literature has emphasized mainly on comparing the standard differential pressure valve shunts with the newer anti siphon valves and flow-regulated valves. The literature has its fair share of both proponents and opponents for these newer valves.[2,10,11] These valves cost many times the standard valves, their efficacy are still questionable and are not freely available in our country. Majority of our patients are not able to afford these shunts. In our study, we used the Chhabra shunt, which is very cheap and freely available in our country. The Chhabra shunt is a unitized shunt system that incorporates a proximal slit-in spring valve. A prospective study by Warf compared the outcome analysis of Chhabra and that of Codman-Hakim in a developing country and found no difference in outcome between these two shunt types.[12] Previous literature does not specify whether to use low- or medium-pressure shunts or the indications for either.

A retrospective analysis by Robinson, Kaufman and Park (2001) in 200 patients less than 1 year old considered medium-pressure valve better than low-pressure valve, and concluded that only significant controllable factor associated with shunt malfunction was the valve opening pressure, and explanation for the difference in the outcome was that a low-pressure valve allows slightly more drainage of cerebrospinal fluid leading to smaller ventricles with increased predisposition to proximal occlusion.[6]

The best method to recognize hydrocephalus and following its course is via the VHR (normal VHR is 24–33%); any value above that is considered abnormal.[13]

Our study was conducted to clarify and elicit if the choice of shunt pressure selection affects the outcome in pediatric hydrocephalus. Both our groups were comparable in relation to the age of the patients. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the brain, an effective tool in diagnosing progressive ventricular dilatation, permitted frequent assessment and was therefore ideally suited for continuous follow-up in cases with open fontanalle.[14] Patients with fused fontanalle and patients with congenital hydrocephalus underwent CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging head for objective assessment of the VHR and a proper evaluation of the intracranial pathology causing hydrocephalus.

Beside symptomatic improvement, both groups show significant decrease in VHR in follow-up, but there is statistically no difference in the change in ratio in comparing both groups (P = 0.8907). It was expected that low-pressure shunts would have better resolution of ventricular dilatation and higher incidence of slit ventricle syndrome as compared with the medium-pressure shunts.[1] However, in our study, the resolution of ventricular system dilatation showed no difference in either group. Shunts’ outcome were also assessed on the basis of complications and need of redo surgery. On an average, each patient of hydrocephalus is likely to have two to three operations throughout their life for shunt revisions; about 40–60% of shunt develops complication at some stage. One-third of these complications occur within the first year of shunt placement.[15,16] The total complication in our study was 20%, which compares favorably with the results in the literature partly due to a lower incidence of postmeningitis hydrocephalus in our study. The group-wise complication rates in groups A and B were 21% and 19%, respectively. The incidence of shut blockage was found in 10% of the total cases, two in each group. However, shunt breakage was found only in one case of group B. Shunt infection was found in two cases of group A and in one case in group B.

This randomized prospective study demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the outcome when either low-pressure or medium-pressure shunts are used in pediatric hydrocephalus. The degree of resolution of dilated ventricles was also found to be independent of shunt opening pressure. There was no difference in complication rates with either shunt types.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grover S, Menon P, Samujh R, Rao KL. Congenital hydrocephalus: A comparative study on the efficacy and complications after low versus medium pressure ventriculoperitoneal shunts. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2004;9:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack IF, Albright AL, Adelson PD. A randomized controlled study of a programmable shunt valve versus a conventional valve for patients with hydrocephalus.Hakim-Medos Investigator group. J Neurosurg. 1999;45:1399–408. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199912000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake JM, Kestle JR, Milner R, John MR, Joseph P, Haines S, et al. Randomized trial of CSF shunt valves design in paediatric hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:294–305. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199808000-00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake JM, Kestle JR, Bilting C, John MR, Haines S, Joseph P. Evolution of CSF shunt valves design in paediatric hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 1989;32:191–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boon AJ, Trans JT, Delwel EJ. Dutch normal pressure hydrocephalus study: Randomized comparison of low and medium pressure shunts. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:490–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson S, Kaufman BA, Park TS. Outcome analysis of initial neonatal shunts: Does the valve makes a difference? J Paediatr Neurosurg. 2002;37:287–94. doi: 10.1159/000066307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michael S, Turner MD. The treatment of hydrocephalus: A brief guide to shunt selection. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:314–23. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(95)80056-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mc Quarrie IG, Schrer PB. Treatment of adult onset obstructive hydrocephalus with low or medium pressure CSF shunts. Neurology. 1982;32:1057–61. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.9.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson A, Jenson C, Bliting M, Ekohlm S, Stephensen H. Does the shunt opening pressure influence the affect of shunt surgery in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1992;117:15–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01400629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matson D, Becker DP, Nulsen FE. Control of Hydrocephalus by valve-regulated venous shunt: Avoidance of complications in prolonged shunt maintenance. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:376–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1968.28.3.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sainte-Rose C, Piatt J, Jr, Renier D, Pierre-Kahn A, Hirsch JF, Hoffman HJ, et al. Mechanical complications in shunts. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1991;17:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000120557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warf BC. Comparision of 1-year outcome for the Chhabra and Codman-Hakim micro precision shunt systems in Uganda: A prospective study in 195 children. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(Suppl 4):S358–62. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.102.4.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appareti KE, Johnson ML. Ultrasound evaluation of neonatal brain. In: Hagen-Ansert SL, editor. Textbook of diagnostic ultrasonography. USA: C.V. Mosby; 1983. pp. 270–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boon AJ, Tans JT, Delwel EJ, Egeler-Peerdeman SM, Hanlo PW, Wurzer HA, et al. Dutch Normal-Pressure Hydrocephalus Study: Randomized comparison of low and medium pressure shunts. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:490–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trost A. Is there a reasonable differential indication for different hydrocephalus shunt systems? Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:189–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00277652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sainte-Rose C, Piatt J, Jr, Renier D, Pierre-Kahn A, Hirsch JF, Hoffman HJ, et al. Mechanical complications in shunts. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1991;17:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000120557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]