Abstract

Aim:

To assess the usefulness of ultrasonography in the differentiation of causes of chronic cervical lymphadenopathy in children.

Materials and Methods:

Children with palpable cervical lymph nodes were included. An ultrasonographic examination was performed to delineate multiple lymph nodes, irregular margins, tendency towards fusion, internal echos, the presence of strong echoes and echogenic thin layer.

Results:

The total number of patients was 120. Echogenic thin layer and strong internal echoes were specific for tuberculosis. Long axis to short axis (L/S) ratio was more than 2 in most of the tubercular nodes (85.71%). Hilus was present in 50 (73.53%) tubercular lymphadenitis, 12 (40%) lymphoma and 10 (62.5%) cases with metastatic lymph nodes. Hypoechoic center was present in 60 (88.24%) tubercular lymphadenitis cases followed by 62.5% metastatic and 60% malignant lymphoma cases.

Conclusions:

Ultrasonography is a non-invasive tool for lymph nodal evaluation in children. It may be used to differentiate cervical lymphadenopathy with different etiologies in children. When correlated clinically, it may avoid biopsy in a patient.

KEY WORDS: Cervical lymphadenopathy, lymphoma, tuberculosis, ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Cervical lymphadenopathy is usually defined as cervical lymph nodal tissue measuring more than 1 cm in diameter.[1,2] In India, the most common cause of cervical lymphadenopathy in children is tuberculosis.[3] Ultrasonography (USG) has been introduced into the evaluation of cervical lymphadenopathy as a non-invasive examination. A lot of work has been done on the role of USG for the evaluation of cervical lymphadenopathy[4–7] in the context of the Western population where tubercular cervical lymphadenopathy is a rare entity. Moreover, there is no exclusive pediatric series comparing various etiologies of chronic cervical lymphadenopathy.

The purpose of the present study was to assess the usefulness of USG in the differentiation of causes of chronic cervical lymphadenopathy, viz. cervical tubercular lymphadenitis, from malignant lymphoma and metastatic lymph nodes in children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective study from February 2009 to February 2011. An informed consent was taken from each child's parents/guardian. The study was approved by the hospital ethical committee. The criterion for selection of the patients was palpable cervical lymph nodes for more than 1 month duration. After a thorough clinical evaluation and USG of the cervical nodes, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC)/biopsy of the clinically palpable lymph node from the same site was performed. The cervical lymph nodes were classified as described by Hajek et al.[8]

USG Evaluation of Cervical Lymphadenopathy

Ultrasonographic examinations were performed using 7.5 MHz linear transducer (Logic 400, Wipro GE, Bangalore, Karnataka, India). The measurements were made in the plane that showed a maximum cross-sectional area of the node. All cervical lymph nodes detected on ultrasonography were included in the study. Author 3, who was blinded about the FNAC/biopsy report to avoid any bias, read the sonograms.

Ultrasonographic characteristics of the nodes included delineation of multiple lymph nodes, irregular margins, tendency towards fusion, internal echoes, the presence of strong echoes, and posterior enhancement. Multiple lymph nodes were defined as involvement of more than two nodes. Partial or complete disappearance of a borderline echo between the lymph nodes was defined as fusion or matting. The internal echo of lymph nodes was assessed for the presence of hypoechoic echogenicity, i.e. hypoechoic central portion of the node as compared with the peripheral portion of the node. The irregular margin was defined as fine alteration of the node margin. The strong echoes were defined as single or multiple coarse, high-echo spots located focally either in the central or the peripheral area in the nodes. When the structures posterior to the lymph node were more echogenic than neighboring structures, it was classified as having acrogenic thin layer or posterior enhancement.

The shape of the cervical nodes was assessed by the L/S (long axis to short axis) ratio. A L/S ratio <2 indicated a round node, whereas a L/S ratio >2 indicated an oval or elongated node. An abnormal lymph node with a L/S ratio <2 was considered a positive result for malignancy.[9,10]

The nodal hilus was identified as an intranodal echogenic structure continuous with the surrounding fat. The lymph nodes with a sharp border were considered to be abnormal. In case of non-cooperation, the patients were sedated. The results were analyzed by the Fisher's exact probability test.

RESULTS

There were 120 patients. All the patients had palpable cervical lymph nodes. The mean age of the patients was 6 years (range 3–11 years). The duration of illness was 1 month to 6 months in 52 (43.33%) patients, 6 months to 1 year in 28 (23.33%) patients, 1–2 years in 24 (20%) patients and more than 2 years in 16 (13.33%) patients.

Clinically, a total of 192 lymph nodes were detected. There were 30 (15.63%) nodes in the submental and submandibular groups, 21(10.94%) in the upper cervical group, 45 (23.44%) in the middle cervical, 41 (21.35%) in the lower cervical and 55 (28.65%) in the posterior triangle groups. The total number of patients having enlarged submental and submandibular lymph nodes was 24 (20%). Sixteen (13.33%) had upper cervical lymphadenopathy, 28 (23.33%) had mid cervical and 25 (20.83%) had lower cervical lymphadenopathy. The remaining 27 (22.5%) had posterior triangle lymphadenopathy.

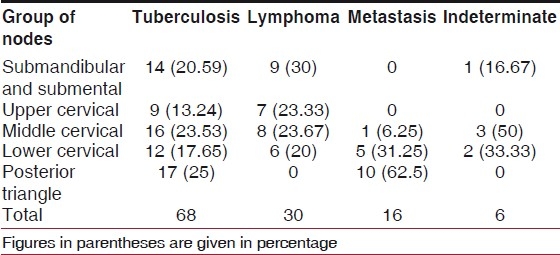

FNAC/biopsy revealed tuberculosis in 68 (56.67%), lymphoma in 30 (25%), metastatic in 16 (13.33%) and indeterminate in six (5%) of the patients. The most common cause of cervical lymphadenopathy was tuberculosis [Table 1].

Table 1.

Pathological involvement of various groups of cervical nodes according to their site (numbers in the brackets are percentages of the respective group)

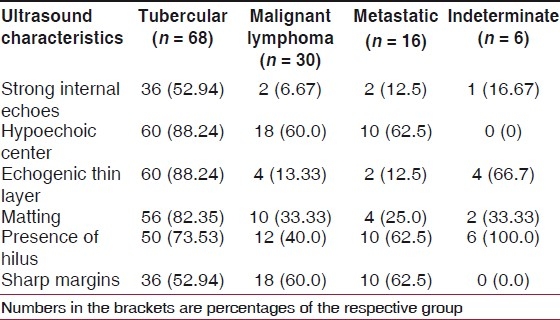

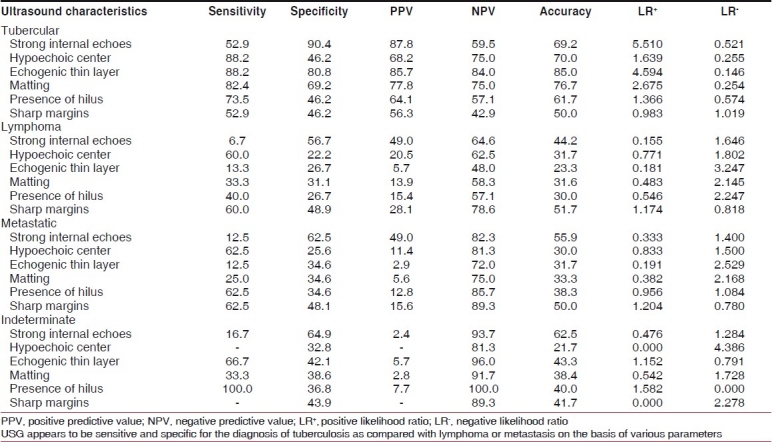

On ultrasonography, besides presence of hilus and sharp margins, all other findings were more commonly seen in the tubercular group [Table 2, Figures 1 and 2]. All nodes in one patient showed the same characteristics.

Table 2.

Ultrasonography findings of the cervical lymph nodes and their correlation with the cytological diagnosis

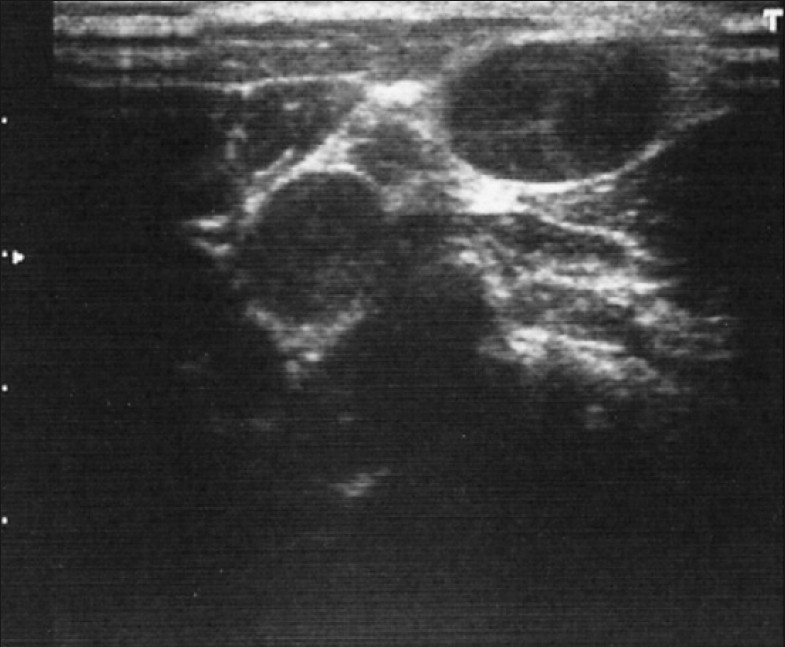

Figure 1.

Well-defined, hypoechoic, oval lesions in cervical nodes. Echogenic thin layer is absent and margins are regular, suggestive of either metastasis or malignant lymphoma

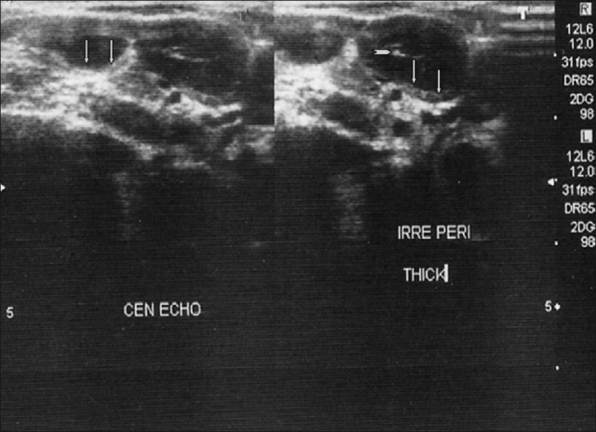

Figure 2.

Multiple, well-defined hypoechoic nodes with echogenic thin layer and strong internal echoes suggestive of tuberculosis. The vertical arrows are pointing toward the echogenic thin layer and the transverse arrowhead is pointing toward the internal echo

For pairwise comparison of the four pathological types (viz. tuberculosis, lymphoma, metastasis and indeterminate), two-tailed Fisher's exact test was performed for each of the six variables, i.e. strong internal echoes, hypoechoic center, echogenic thin layer, matting, presence of hilus and sharp margins. Except sharp margins, all other USG findings were more commonly noticed in tubercular lymphadenitis as compared with lymphoma. Except for presence of hilus and sharp margins, all other USG findings were more commonly noticed in the tubercular lymphadenitis as compared with metastasis. The difference was statistically significant for all these findings (P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between malignant lymphoma and metastatic group for any USG finding. The total number of lymph nodes detected by USG was 484.

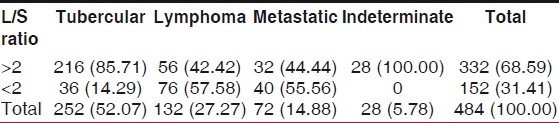

According to the L/S ratio, the distribution of pathological types is presented in Table 3. The maximum lymph nodes, 332 (68.59%), had L/S ratio >2. On pairwise comparison of the different cytological diagnoses in the L/S ratio >2 group, the difference was statistically significant in comparison of tuberculosis with malignant lymphoma and metastasis (P < 0.05). The difference between malignant lymphoma and metastasis was insignificant (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Ultrasonography evaluation of cervical lymph nodes based on L/S ratio (long axis to short axis ratio)

The screening criteria of the various etiologies are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Screening criteria of the diagnosis of various pathological conditions

DISCUSSION

Enlarged cervical lymph nodes are common in children.[11] During the first 6 years of life, neuroblastoma and leukemia are the most common tumors associated with cervical lymphadenopathy, followed by rhabdomyosarcoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. After 6 years, Hodgkin's lymphoma is the most common tumor associated with cervical lymphadenopathy, followed by non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.[11]

The present study was a prospective study in which 120 children were selected as a study group, all having palpable neck node as the selection criterion. We included only chronic cases in our study having symptoms for at least 1 month. Apart from tuberculosis, other causes of infectious chronic cervical lymphadenitis are non-tuberculous mycobacteria,[12] cat scratch disease and fungal, parasitic and opportunistic infections like nocardia, actinomyces, toxoplasma gondii, and histoplasma capsulatum etc.[1]

In our study, tuberculosis involved any group of lymph nodes, but the supraclavicular group was most commonly involved. All causes of metastasis were infraclavicular and, hence, commonly involved the supraclavicular group. The lymphoma involved the submandibular group and the jugular group. These findings have also been noticed by others;[13,14] however, their study subjects were not solely children. Thus, site of the affected lymph node may provide some idea as to which pathology is affecting the nodes.

Chang et al.[9] noticed that benign lymph nodes had a significantly larger L/S ratio than did malignant nodes.[9,15] Na et al.[10] noticed that L/S ratio <2 had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 61% for malignancy, which has not been supported by Moritz et al.[16] We have, however, noticed the ratio to be of benefit in children.

Asai et al.[5] reported that strong internal echoes and echogenic thin layer were characteristic of tubercular cervical lymphadenopathy. We had noticed strong internal echos in about 50% of our study group and echogenic thin layer in about 90% of the patients, suggesting that strong internal echoes are probably more commonly seen in children. The strong echo histologically reflected calcification or hyalinosis in caseous necrosis of the lymph nodes. The echogenic thin layer histopathologically corresponded to a specific granuloma tissue layer surrounding a caseous necrosis. It is to be noticed that hypoechoic mass is the common finding described in the literature as characteristic of tubercular lymphadenopathy,[5,17] which was also noticed by us.

Tuberculous nodes are predominantly hypoechoic, which is probably related to the high incidence of intranodal cystic necrosis.[13] The metastatic nodes are usually hypoechoic when compared with the adjacent muscles. However, metastatic nodes from papillary carcinoma of the thyroid tended to be hyperechoic.[13,18] Lymphomatous nodes were previously reported to have a “pseudocystic” appearance, hypoechoic with posterior enhancement. However, with the use of newer transducers, lymphoma nodes demonstrate intranodal reticulation, and the pseudocystic appearance is less likely to be seen.[12] The same findings have been noticed by us in children.

The matting of the lymph nodes is common in tuberculous lymphadenitis, and is believed to be due to the periadenitis.[13] As matting of lymph nodes is common in tuberculosis, it is a useful feature in distinguishing tuberculosis from other diseases.[4] In tuberculosis, node borders are not sharp probably due to active inflammation of the surrounding soft tissues.[13] Malignant nodes (including metastases and lymphoma) tend to have sharp borders, whereas benign nodes usually do not have such sharp borders.[19]

The requirement of sedation during the scan has not been described specifically in the literature. We had, however, used sedation for proper evaluation of the patients in case of apprehension and non-cooperation. The use of sedation is an option when patient motion prevents smooth and complete scanning of the cervical nodes.

The limitation of our study is that a large proportion of indeterminate biopsies have not been considered in the context of the utility of ultrasound for differentiating malignant and benign nodes, but it is due to the fact that the focus of this article is differentiation of tuberculosis, lymphoma and metastasis.

There are many adult series evaluating the satisfactory role of ultrasonography to help in differentiating different causes of chronic cervical lymphadenitis.[4,5,10,18,20] Our series is probably the first pediatric series evaluating the usefulness of ultrasonography for chronic cervical lymphadenitis.

Thus, it can be concluded that use of ultrasonography is feasible as a non-invasive tool for nodal evaluation in children. It may be used to differentiate cervical lymphadenopathy with different etiologies in children. When correlated clinically, it may avoid biopsy/FNAC in a patient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study has been funded by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gosche JR, Vick L. Acute, subacute, and chronic cervical lymphadenitis in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:99–106. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darville T, Jacobs RF. Lymphadenopathy, lymphadenitis, and lymphangitis. In: Jenson HB, Baltimore RS, editors. Pediatric infectious diseases: Principles and practice. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 2002. pp. 610–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marais BJ, Donald PR. Peripheral tuberculous lymphadenitis. In: Seth V, Kabra SK, editors. Essentials of Tuberculosis in children. 3rd ed. New Delhi: Jaypee; 2006. pp. 134–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahuja A, Ying M. Grey-scale sonography in assessment of cervical lymphadenopathy: Review of sonographic appearances and features that may help a beginner. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38:451–9. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asai S, Miyachi H, Suzuki K, Shimamura K, Ando Y. Ultrasonographic differentiation between tuberculous lymphadenitis and malignant lymph nodes. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:533–8. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ying M, Ahuja AT, Evans R, King W, Metreweli C. Cervical lymphadenopathy: Sonographic differentiation between tuberculous nodes and nodal metastases from non-head and neck carcinomas. J Clin Ultrasound. 1998;26:383–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199810)26:8<383::aid-jcu2>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ying M, Ahuja A, Brook F. Accuracy of sonographic vascular features in differentiating different causes of cervical lymphadenopathy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:441–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajek PC, Salomonowitz E, Turk R, Tscholakoff D, Kumpan W, Czembirek H. Lymph nodes of the neck: Evaluation with US. Radiology. 1986;158:739–42. doi: 10.1148/radiology.158.3.3511503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang DB, Yuan A, Vu CJ, Luh KT, Kuo SH. Differentiation of benign and malignant cervical lymph nodes with Color Doppler Sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:965–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.4.8141027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Na DG, Lim HK, Byun HS, Kim HD, Ko YH, Baek JH. Differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy: Usefulness of color doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1311–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.5.9129432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung AK, Robson WL. Childhood cervical lymphadenopathy. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindeboom JA, Smets AM, Kuijper EJ, van Rijn RR, Prins JM. The sonographic characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:1063–7. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahuja A, Ying M. Sonography of neck lymph nodes. Part II: Abnormal lymph nodes. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:359–66. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(02)00585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ying M, Ahuja AT. Ultrasound of neck lymph nodes: How to do it and how do they look? Radiography. 2006;12:105–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niedzielska G, Kotowski M, Niedzielski A, Dybiec E, Wieczorek P. Cervical lymphadenopathy in children--Incidence and diagnostic management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moritz JD, Ludwig A, Oestmann JW. Contrast-enhanced color doppler sonography for evaluation of enlarged cervical lymph nodes in head and neck tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1279–84. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta KB, Kumar A, Sen R, Sen J, Vermas M. Role of ultrasonography and computed tomography in complicated cases of tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis. Indian J Tuberc. 2007;54:71–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosario PW, de Faria S, Bicalho L, Alves MF, Borges MA, Purisch S, et al. Ultrasonographic differentiation between metastatic and benign lymph nodes in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1385–9. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shozushima M, Suzuki M, Nakasima T, Yanagisawa Y, Sakamaki K, Takeda Y. Ultrasound diagnosis of lymph node metastasis in head and neck cancer. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1990;19:165–70. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.19.4.2097226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumi M, Ohki M, Nakamura T. Comparison of sonography and CT for differentiating benign from malignant cervical lymph nodes in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1019–24. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.4.1761019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]