Abstract

Migraine constitutes 16% of primary headaches affecting 10-20% of general population according to International Headache Society. Till now nonsteroidalanti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), opioids and triptans are the drugs being used for acute attack of migraine. Substances with proven efficacy for prevention include β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, antiepileptic drugs and antidepressants. All the already available drugs have certain limitations. Either they are unable to produce complete relief or 30-40% patients are no responders or drugs produce adverse effects. This necessitates the search for more efficacious and well-tolerated drugs. A new class of drugs like angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) and angiotensin II receptor antagonists have recently been studied for their off label use in prophylaxis of migraine. Studies, done so far, have shown results in favour of their clinical use because of the ability to reduce number of days with headache, number of days with migraine, hours with migraine, headache severity index, level of disability, improved Quality of life and decrease in consumption of specific or nonspecific analgesics. This article reviews the available evidence on the efficacy and safety of these drugs in prophylaxis of migraine and can give physician a direction to use these drugs for chronic migraineurs. Searches of pubmed, Cochrane database, Medscape, Google and clinicaltrial.org were made using terms like ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists and migraine. Relevant journal articles were chosen to provide necessary information.

KEY WORDS: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, migraine

Introduction

Migraine is a primary headache disorder which predominantly affects young adults particularly women.[1] It has been shown to affect 18% of women and 6.5% of men in United States.[2] Worldwide approximately 240 millions of people have an estimated 1.4 billion attacks of migraine each year. Severe migraine has been included in the list of global burden of diseases by World Health Organization (WHO) and it represents a serious health problem both for individuals and society as this disabling disorder has a direct impact on quality of life.[3]

Effective management of migraine depends on accurate diagnosis ruling out other causes for headache. In 1988 the International Headache Society published criteria for the diagnosis of a number of different headache types.[4] Those for migraine headaches with or without aura are reproduced below:

ICH Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine

Migraine without Aura (MO)

This is diagnosed when there are at least five headache attacks lasting 4-72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated), which has at least two of the four following characteristics:

Unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity (inhibits or prohibits daily activities), aggravated by walking stairs or similar routine physical activity During headache at least one of the two following symptoms occur: Phonophobia and photophobia, nausea and/or vomiting

Migraine with aura (MA) is diagnosed when:

At least two attacks occur fulfilling with at least three of the following:

One or more fully reversible aura symptoms indicating focal cerebral cortical and/or brain stem functions, at least one aura symptom develops gradually over more than four minutes, or two or more symptoms occur in succession. No aura symptom lasts more than 60 minutes; if more than one aura symptom is present, accepted duration is proportionally increased. Headache follows aura with free interval of at least 60 minutes (it may also simultaneously begin with the aura. Migraine with typical aura is diagnosed when there is homonymous visual disturbance, unilateral paresthesias and/or numbness, unilateral weakness and aphasia or unclassifiable speech difficulty.

Management includes nonpharmacological, behavioral and physical measures and pharmacotherapy. Pharmacological treatment of migraine has equally important therapeutic and prophylactic components. Besides NSAIDS, opioids, and ergot alkaloids, triptans are the major contributor to the management of acute attack of migraine but producing partial relief or providing consistent response in 50-60% of patients. Even triptans can themselves induce headache in some patients. Prophylactic treatment is indicated if acute treatment alone is inadequate, patient is experiencing more than two to three attacks per month, when acute therapy is contraindicated, use of abortive medicine more than twice a month, presence of migraine with prolonged aura, hemiplegic migraine, migranous infarction.[3,5] A variety of diverse pharmacological classes of drugs are in use for prevention of attack. The goal of preventive therapy is to improve patients’ quality of life by reducing migraine frequency, severity, and duration, and by increasing the responsiveness of acute migraine to treatment.[5] The mechanism of action of most of prophylactic drugs is poorly understood as they have multiple mechanisms. It is postulated that their mode of action converge on twotargets that is inhibition of cortical excitation and resting nociceptive dysmodulation.[6]

Trials have favoured the use of drugs like β-blockers (propranolol, timolol, metoprolol), antidepressant (amitriptyline), anticonvulsants (divalproex, topiramate, tiagabin, levetiracetam, zonisamide) as the first-line drugs for prevention but none is effective in all cases and none abolishes the attacks totally.[6] Few clinical trials done so far have failed to prove any superiority of one prophylactic agent over the other.

Despite the availability of a number of drugs for aborting/preventing the migraine, a significant numbers of migraineurs are unable to achieve satisfactory results. Most of the drugs are associated with adverse drug reactions (ADRs) which are common and severe too.[7] This has necessitated the need for searching altogether newer classes of drugs with different mechanisms which may be more efficacious and better tolerated than the already existing ones. Some clinical trials and case reports have justified the benefits of SSRIs, high-dose riboflavin, monteleukast sodium, magnesium, botulinum toxin and coumarin derivatives in migraine.[2,7–9]

Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzymes Inhibitors in Migraine

A new target which has recently caught the attention of researchers in migraine is ‘Renin Angiotensin System (RAS).’ RAS has neurophysiological, chemical and immunological effects that are relevant to pathophysiology of migraine.[1] This fact directed the scientists to explore the usefulness of angiotensin-converting enzymes inhibitors (ACE inhibitors)/Angiotensin II receptor antagonists in the management of migraine. These drugs are extensively used for treatment of hypertension and congestive heart failure. The use of ACE inhibitors as prophylactic agents in headache was first proposed by Siceturi in 1981. Dramatic improvement was seen in 50% patients experiencing improvement in headache and 31% had partial relief. The rationale for this was inhibition of carboxypeptidase, an enkephalin-inactivating enzyme.[10] This hypothesis was further supported by Baldi et al., in 1986.[11] In 1992, research by Paterna et al., found the utility of captopril in preventing migraine.[12] These initial steps strongly led to further research on the use of these drugs in migraine. There is no clear underlying mechanism of action relating, as the effect produced by them is probably not due to their effects on blood pressure.[1] It has been suggested that the effect of ACE inhibitors can be related to their ability to increase norepinephrine and serotonin action on vascular tone.[7] The postulated pharmacological effects which can be relevant in migraine are inhibition of conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, inhibition of free radicals, alteration of sympathetic activity, increase in prostacyclin synthesis, inhibition of degradation of bradykinin, enkephalin and substance P.[8]

Acting through angiotensin receptors, angiotensin II also modulates cerebrovascular flow and has effect on homeostasis, autonomic pathways and neuroendocrine system. In addition it has action on potassium and calcium channels too in cells.[13,14] Angiotensin II has been found experimentally to influence the tonic modulation of pineal melatonin synthesis.[15] Angiotensin II has been shown to activate Neurokin in Factor Kappa B through AT1 and AT2 (Angiotensin receptors) receptors which is associated with increased expression of NO synthase.[16,17]

Thus angiotensin, by its multifaceted actions, is involved in pathogenesis of migraine providing one additional mechanism by virtue of which ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists possess prophylactic role in migraine. Recently it has been found that genetic basis of migraine contributes a lot to define the role of ACE inhibitors/Angiotensin II receptor antagonist in migraine prophylaxis. In human serum, ACE levels are genetically determined. Individuals who are homozygous for DD allele (deletion allele) have increased ACE activity. Migraine is more common in persons with DD allele correlating higher ACE activity to more migraine attacks.[18,19] In a study, it has been seen that incidence of DD genotype in migraine with aura was significantly higher than controls (25.9% versus 12.5%, P value <0.01).[20]

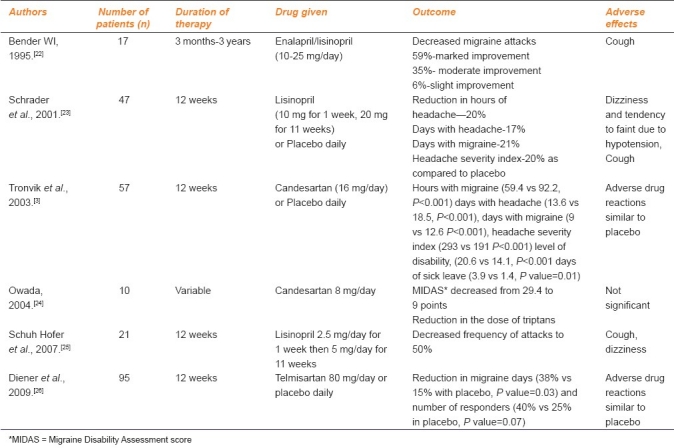

Studies have shown that ACE inhibitors (enalapril, lisinopril) as well as angiotensin II receptor antagonists (candesartan, telmisartan) have proved to be effective in reducing frequency as well as severity of migraine attacks with minimal side effects. Outcome measures studied in most of trials showed decrease in number days of headache, number of days with migraine, hours with migraine, headache severity index, level of disability, improved quality of life and decrease in consumption of specific or nonspecific analgesics.

Case series, open label studies, randomized controlled clinical trials and meta-analysis have been done so far evaluating the role of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists for prevention of migraine. In a meta-analysis done by Etminanet al., data from 27 studies involving 12,110 patients were included. The risk of headache was about one-third lower in patients taking an angiotensin II receptor antagonist than in those taking placebo (RR 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.62 to 0.76; the test of heterogeneity was negative, P value 0.2). The odds ratio for having a headache per unit dose of the reference drug losartan was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.68-0.93).[21]

Relevant studies predicting the clinical efficacy and tolerability of ACE inhibitors/Angiotensin II receptor antagonists are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical studies of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists in prophylaxis of migraine

Results of the above-mentioned studies clearly indicate the effectiveness and safety of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists, providing a new hope for chronic migraineurs. A special indication for the use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists is migraineurs with bronchial asthma, intermittent claudication and conduction defects. Pregnancy is a known contraindication to the use of these drugs because of their ability to produce teratogenic effects in second and third trimester. Regarding tolerability, these drug classes have well established safety profile.

Conclusions

ACE inhibitors and Angiotensin II receptor antagonists show a potential in prophylactic management of migraine. Patients with frequent headaches who do not respond to conventional prophylactic agents or in whom these drugs are contraindicated, trial of ACE inhibitors/Angiotensin II receptor antagonists can be useful. Their use should be considered as a long-term therapeutic approach to migraine prophylaxis. Further assessment by larger studies is warranted in future to evaluate whether the positive effects are shared by all ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Schrader H, Bovim G. Involvement of the renin-angiotensin system in migraine. J Hypertens. 2006;24:139–43. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000220419.86149.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snow V, Wall EM, Mottur-Pilson C. Pharmacological management of acute attacks of migraine and prevention of migraine headache. Ann Intern Med. 2002;37:840–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Sand T, Bovim G. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache classification committee of the IHS. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modi S, Lowder DM. Medications for migraine prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:72–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramadan NM. Current trends in migraine prophylaxis. Headache. 2007;47(Suppl 1):S52–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar R. Recent advances in migraine preventive treatment on the basis of pathophysiological considerations. Trendz. 2007;5:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahimtoola H, Buurrna H, Tijssen CC, Leufkens HG, Egberts AC. Reduction in the therapeutic intensity of abortive migraine drug use during ACE inhibitor therapy-A pilot study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:41–7. doi: 10.1002/pds.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipton RB. Conventional management and novel modalities for improved treatment of chronic migraine. Neurology. 2009;72(Suppl 1):S1–2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344252.29199.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sicuteri F. Enkephalinase inhibition relieves pain syndromes of central dysnociception (migraine and related headache) Cephalalgia. 1981;1:229–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1981.0104229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldi E, Conti P, Conti R, Fanciullacci M, Michelacci S, Salmon S, et al. Hypernociceptive syndromes and pharmacological inhibition of endogenous opioid degradation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1986;6:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, Martino S, Arrostuto A, Ingurgio NC, Parrinello G, et al. Captopril versus Placebo in the prevention of hemicranias without aura-A randomized double blind study. Clin Ter. 1992;141:475–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura Y, Ito T, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 blockade normalizes cerebrovascular auto regulation and reduces cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2000;31:2478–86. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen AM, Moeller I, Jenkins TA, Zhuo J, Aldred GP, Chai SY, et al. Angiotensin receptors in the nervous system. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47:17–28. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltatu O, Afeche SC, Jose dos Santos SH, Campos LA, Barbosa R, Michelini LC, et al. Locally synthesized angiotensin modulates pineal melatonin generation. J Neurochem. 2002;80:328–34. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Konig S, Wittig B, Egido J. Angiotensin II activates nuclear transcription factor κB through AT1 and AT2 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2000;86:1266–72. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.12.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuter U, Chiarugi A, Bolay H, Moskowitz MA. Nuclear factor-kappaB as a molecular target for migraine therapy. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:507–16. doi: 10.1002/ana.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kara I, Ozkok E, Aydin M, Orhan N, Cetinkaya Y, Gencer M. Combined effects of ACE and MMP-3 polymorphisms on migraine development. Cephalgia. 2007;27:235–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, D’Angelo A, Seidita G, Tuttolomondo A, Cardinale A, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene deletion polymorphism determines an increase in frequency of migraine attacks in patients suffering from migraine without aura. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:133–6. doi: 10.1159/000008151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowa H, Fusayasu E, Ijiri T, Ishizaki K, Yasui K, Nakaso K, et al. Association of the insertion/deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene in patients of migraine with aura. Neuroscience. 2005;2:129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etminan M, Levine MA, Tomlinson G, Rochon PA. Efficacy of angiotensin II receptor antagonists in preventing headache systematic overview and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2002;112:642–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender WI. ACE inhibitors for prophylaxis of migraine headaches. Headache. 1995;8:470–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3508470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Sand T, Bovim G. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): Randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7277.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owada K. Efficacy of candesartan in the treatment of migraine in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:441–6. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuh-Hofer S, Flach U, Meisel A, Israel H, Reuter U, Arnold G. Efficacy of lisinopril in migraine prophylaxis – An open label study. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:701–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener HC, Gendolla A, Fruersenger A, Evers S, Straube A, Schumacher H, et al. Telmisartan in migraine prophylaxis: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:921–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]