Abstract

Objective:

To determine the drug utilization pattern of antihyperglycemic agents (AHA) in a tertiary care teaching hospital.

Materials and Methods:

This was a prospective observational study. All the relevant data were collected and drug utilization pattern of AHA was determined. Direct cost associated with the use of antihyperglycemic medicines was calculated and consumption of the antihyperglycemic medicines was measured as defined daily dose (DDD)/100 bed-days. The adverse drug reactions (ADRs) related to anti-diabetic medicines were monitored.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Chi square test (χ2), mean±standard deviation.

Results:

During the study period, 350 patients diagnosed as diabetes mellitus (DM) were admitted. Insulin was prescribed as monotherapy to 81% and to 52% patients during hospital stay and discharge, respectively. Increase in utilization of insulin was recorded in majority of the patients due to presence of co-morbid conditions or resistance to oral hypoglycemic drugs. Use of insulin at the time of discharge decreased significantly (P<0.05) by 29%. Among the oral AHA, combination of glimepiride with metformin was more prevalent during hospital stay and at the time of discharge monotherapy of metformin followed by glimepiride was more prevalent. During hospital stay, cost of AHA was found to be Rs. 95.27 ± 119.03. The total antihyperglycemic drug consumption in the medicine ward during study period was 13.42 DDD/100 bed-days. Fifty ADRs were reported and descriptions of ADRs were found to be only hypoglycemia.

Conclusion:

The study exhibited a significant increase in the utilization of two drug combination therapies and monotherapy of oral AHA and decrease in the utilization of insulin at the time of discharge.

KEY WORDS: Defined daily dose, diabetes mellitus, drug utilization

Introduction

As per World Health Organization, around 31.7 million individuals in India were affected by diabetes during the year 2000 which may further rise to 79.4 million by the year 2030.[1] Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the chronic disorder emerging as major health problem which increases the rate of morbidity and mortality.[2] Poor management of these two disorders leads to several complications.[3] Management of DM requires both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. Hypoglycemia is the common adverse drug reaction (ADR) of antidiabetic drugs and it is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.[2] In this regard drug utilization study was conducted to determine the drug utilization pattern of antidiabetic medicines during hospital stay and at the time of discharge, cost of antidiabetic drugs and defined daily dose (DDD)/100 bed-days during hospital stay in our setup. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) related to antidiabetic medicines were also monitored during hospital stay.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study conducted for a period of 150 days after approval by Institutional Ethics Committee of JSS College of Pharmacy at JSS Medical College Hospital, Mysore. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before conducting the study.

Inclusion Criteria

Newly diagnosed and known cases of DM with other comorbidities who were receiving antihyperglycemic medicines and admitted as inpatients were included. Inpatients of either sex and age group of 18 years and above were included.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with gestational diabetes were excluded from the study.

Assessment of Cost of Therapy

Total cost per patient for antidiabetic medicine was calculated. The results were expressed as mean±standard deviation.

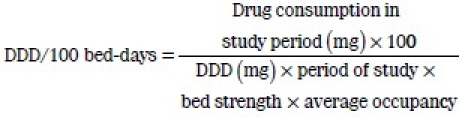

Measurement of Drugs Consumption in Medicine Wards in DDD/100 Bed-days

Drug consumption in medicine wards were measured in DDD/100 bed days. The medicines were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. As per ATC classification system, the medicines are divided into different groups according to the organ or system on which they act and as per their chemical, pharmacological and therapeutic properties.[4] The DDD/100 bed-days were calculated using the following formula:

The average occupancy was calculated by dividing the number of occupied beds by the total number of beds in the medicine wards.

ADR Monitoring

The ADRs related to antidiabetic medicines were monitored and documented in suitably designed ADR documentation form after initial notification of the suspected ADR by physicians. Additional details were collected by review of the patient case records and interview with patients. Severity and causality of the ADRs were assessed by using Modified Hartwig and Seigel[5] scale and Naranjo's Algorithm,[6] respectively. The Modified Hartwig and Siegel scale grades ADRs as Mild (Level 1 and Level 2), Moderate (Level 3, Level 4 (a) and Level 4(b)) and Severe (Level 5, Level 6 and Level 7). Naranjo's Algorithm scale grades causality of ADRs as Definite, Probable, Possible and Unlikely.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the pattern of drugs used in this study, data were subjected to Chi square test (χ2) and percentage value. The level of significance (P value) was set at 0.05. Patient's demographic data were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). The data were analysed using SPSS version 12.0 and Microsoft excel.

Results

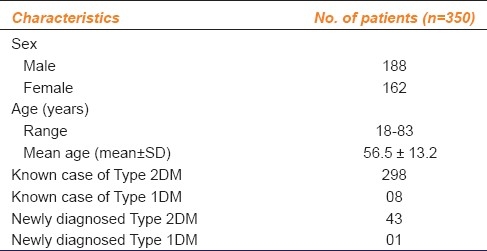

During the study period, 350 patients with DM were admitted in the medicine ward. Of these, 342 subjects were identified as (Type 2 DM) Type 2DM whereas the eight patients were identified as (Type 1 DM) Type 1DM. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Categorization of patients of diabetes mellitus based on demographic characteristics

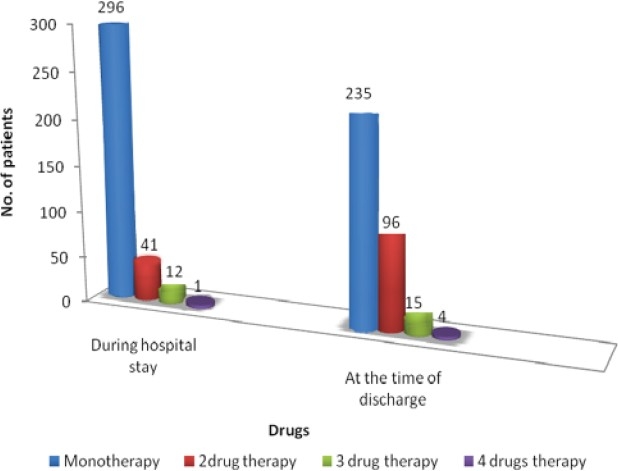

The average number of antidiabetic medicine per prescription was 0.94. Insulin was prescribed as monotherapy to 81% patients during hospital stay and to 52% patients at the time of discharge. The use of insulin at the time of discharge decreased significantly by 29% (from 81 to 52%, P<0.05), while use of metformin increased by 4.5% at the time of discharge (1.7% during hospital stay to 6.2% at the time of discharge, P<0.05). Utilization pattern of glimepiride was similar to metformin (1.7%) during hospital stay but at the time of discharge it was prescribed to 5.7% patients. Its utilization thus increased by 4% (P<0.05).

Dual therapy or combination therapy was prescribed less frequently during hospital stay (11.7%) than at the time of discharge (27.4%). There was a significant (P<0.05) increase in the prescription of two drugs (15.7%) at the time of discharge. The combination of metformin and sulfonylurea were prescribed more often, it was prescribed to 7.4% patients during the hospital stay and at the time of discharge to 22.2% patients. The combination of glimepiride with metformin was most commonly prescribed during hospital stay and at the time of discharge. The combination was significantly (P<0.05) higher by 10.57% (6% during hospital stay and 16.57% at the time of discharge).

Combination of three drugs during hospital stay was found in 12 (3.4%) patients and at the time of discharge in 15 (4.2%) patients. The most prevalent three drug therapy was insulin+metformin+glimepiride. The four drug combination therapy was prescribed to only one patient during hospital stay and to four patients at the time of discharge [Figure 1]. Among glitazones only pioglitazone was prescribed in combination with the 2 drugs, 3 drugs and 4 drugs regimen during hospital stay and at the time of discharge as monotherapy and combination therapy.

Figure 1.

Number of antidiabetic drugs received during hospital stay and at the time of discharge

Comorbid condition was found in 280 patients. Among the 280 patients, majority were suffering from one comorbid condition (158) followed by two conditions (92) and more than two conditions (30). The comorbid conditions found were cardiovascular, respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, nephropathy, cellulites, depression, nephropathy and retinopathy.

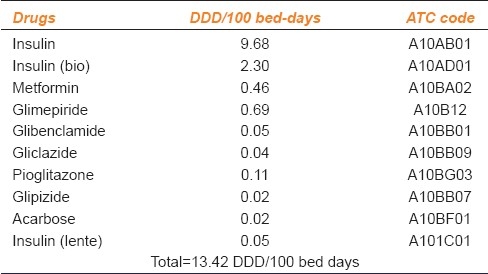

Drug Consumption and Cost Analysis

Drug consumption was calculated in DDD/100 bed days. This unit is applied when in-hospital drug use is considered. The total antidiabetic drug consumption in the medicine wards during study period was 13.42 DDD/100 bed-days [Table 2]. The mean±SD cost of antidiabetic medicines was Rs. 95.27 ± 119.03 for 350 patients during the hospital stay.

Table 2.

DDD/100 bed-days of antidiabetic medicines during hospital stay in medicine wards

Incidence of ADR

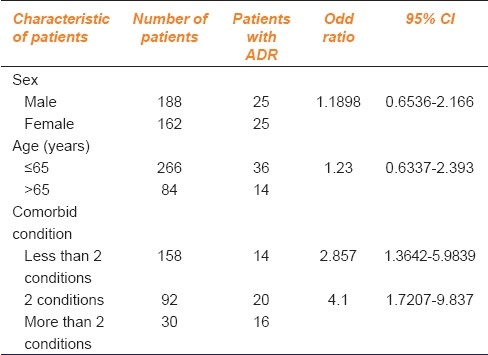

During this study period, a total 50 ADRs (all reported as hypoglycemia) were reported in 50 patients. There was preponderance of ADRs in females compared to males. Of 162 females enrolled, 25 (OR=1.18, CI=0.6536-2.166) experienced hypoglycemia as compared to 25 of 188 males who developed this ADR [Table 3]. Hence females developed hypoglycemia 1.1 times more often than males. Incidence of ADR was 1.23 times higher in patients with who were aged more than 65 years of age [Table 3].

Table 3.

Relation of ADRs with sex, age and comorbid conditions in patients of diabetes mellitus

Incidence of ADR (OR=4.11, CI=1.7207-9.837) was four times higher in patients with more than two co-morbid conditions as compared to patients with two comorbid conditions and 2.8 times higher in patients (OR=2.8, CI=1.364-5.9839) with 2 comorbid condition than those with less than two comorbid conditions. There was a correlation between number of ADRs and the number of comorbid conditions in the patients [Table 3].

It was observed that 27 ADRs were of mild severity (08 ADRs of Mild L1 and 19 ADRs of Mild L2) followed by 23 ADRs were of moderate severity (12 ADRs of Moderate L3 and 11 ADRs of Moderate L4 (a)). None of the ADRs were severe. Among these 27 ADRs were of possible category, followed by 23 ADRs were of probable category on the causality assessment scale.

Discussion

Out of the 350 patients evaluated in our study, 188 (53.72%) were males and 162 (46.28%) were females. Males predominated in the study population which is in agreement with the results of various other studies in India[7] and United States.[8] These results also corroborate with the findings of a cohort study conducted in the U.S. which also reported a male preponderance for DM.[9]

The (mean±SD) age of the patients was 56.5 ± 13.2 years with a range between 18 and 83 years. It was higher than that reported in studies carried out in India (51.5 ± 12.3 years),[10] almost similar to that reported in Hong Kong (56.5 ± 12.6 years).[11] Among 43 newly diagnosed patients with Type 2DM 30% were of the age group of 41-50 years indicating that the risk of Type 2DM increases after the age of 40 years.

A total 280 patients suffered from comorbid condition. Hypertension accounted for 51.95% of the total complications which was lower than in the study reported in Nepal (Hypertension accounted for 70.62% of the total complication).[12] Our study findings are also similar to the study conducted by Arauz-Pacheco et al., in Texas medical center that hypertension is more common complication affecting 20-60% of people with diabetes.[13]

Prescribing Pattern of AHA

The average number of antidiabetic drugs per prescription was 0.94 which is less than 2.27 of that previously recorded in India.[10] In the present study, the most commonly used antidiabetic medicine (monotherapy) was insulin during hospital stay and at the time of discharge. Total 284 (81%) patients were prescribed insulin as monotherapy during hospital stay. Among the 284 patients, 236 patients were with known case of (k/c/o) Type 2DM and eight patients were of k/c/o Type 1DM. Moreover 39 patients were in the category of newly diagnosed Type 2DM and 1 patient in Type 1DM. At the time of discharge total 182 (52%) patients were prescribed insulin as monotherapy. Out of them 156 patients were of k/c/o Type 2DM, seven patients were of k/c/o Type 1DM, 18 patients were of newly diagnosed Type 2DM and one patient was identified as the newly diagnosed Type 1DM. In majority of the patients (80%) the reason for prescribing insulin was stated as presence of various co-morbid conditions (e.g., hypertension, nephropathy, infections, etc.) or resistance to oral hypoglycemic drugs in the patients’ case note. During hospital stay percentage of patients receiving monotherapy as insulin in this study (81%) is higher than that of the previously reported study (11.5%) in New Delhi, India.[10]

In this study, metformin in combination with sulfonylurea was highly prescribed as the two drug oral antidiabetic combination to 7.4% of patients during hospital stay and to 22.2% of patients at the time of discharge. Metformin and sulfonylurea combination was found to be almost similar to that reported in general outpatient clinic (22.4%) and lower than that reported in geriatric specialist clinic (28%) at Hongkong.[14] However, it is higher than that of a study (20%) conducted at Sweden.[15]

Among the second generation sulfonylureas, glimepiride was the most commonly prescribed along with metformin. It was prescribed to 6% of patients during hospital stay and to 16.57% of patients at the time of discharge. Among sulfonylureas, selection of glimepiride and glipizide has been recommended by Texas Diabetes Council because these agents have lower incidence of hypoglycemia than glyburide.[16] In Type 2DM patients who are intensively treated with insulin, the combination of insulin and metformin results in superior glycemic control as compared to insulin therapy alone while insulin requirements and weight gain are less.[17] In this study, insulin and metformin combinations were prescribed to 2.4% of patients during hospital stay and to 3.4% of patients at the time of discharge. Pioglitazone+metformin+insulin+glimepiride combinations were three times more at the time of discharge than during hospital stay. A lower prescribing rate of α-glycosidase inhibitors (0.02%) was noted in this study was slightly lower when compared to the earlier study reported (1.8%) in New Delhi, India, in which lower prescribing rate of α-glycosidase inhibitors was found probably due to high cost or lack of long-term benefits.[10]

During this study, a total 50 patients reported hypoglycemia. Data showed preponderance of ADRs in female subjects compared to males. Advanced age is a risk factor for development of ADRs due to pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic changes which together with impairment of homeostatic mechanisms and coexisting diseases lead to significant increase in the incidence of ADRs.[18] Present study strengthens the fact that age and co-morbidity have significant role in the occurrence of ADRs [Table 3]. It was also observed that patients with nephropathy have a high incidence of hypoglycemia (20 out of 50 patients had nephropathy). This confirms the findings of a study reported by Rutsky et al. This is because of anosmic or vanished renal glucose production.[19]

Cost of the Therapy and Drug Consumption

The mean±SD cost of antidiabetic drugs was Rs 95.27 ± 119.03 during hospital stay for 350 patients. Drug consumptions were calculated with respect of DDD concept to overcome objection against traditional units of measurement of drug consumption.[4] DDD is defined as the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults. It provides a fixed unit of measurement independent of the price and formulations. For hospital inpatients DDD/100 bed-days provide a rough estimate of drug consumptions.[4] The utilization of insulin(R), insulin (Bio) was 9.68 and 2.38 DDD/100 bed-days respectively. Total antidiabetic drug consumption in the medicine wards was 13.42 DDD/100 bed-days.

This study shows that prescribing trend has been monotherapy with insulin followed by two oral AHA in inpatients. Two drug combination therapies and monotherapy with oral AHA was evident in outpatients. There was an increase in number of ADRs in elder patients and those with comorbid conditions.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to the JSS University, Principal, Dr. HG Shivakumar, JSS college of Pharmacy, Dr. G. Parthasarthi, Head of the Department, Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy and the staff of Department of Medicine, JSS Medical College Hospital for their support during the study. The authors are also indebted to Dr. Hege Salvesen Blix, senior advisor WHO Collaborating Centre Drug Statistic Methodology, for his assistance in answering ours queries regarding the use of DDD as a measure of drug consumption and also for providing us the related literatures.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diabetes fact sheet. 2008. [Last Accessed on 2008 Dec 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/

- 2.Trplitt LC, Reasner AC, Isley LW, DiPiro JT, Talbert RL. Diabetes mellitus. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Rosey LM, editors. Pharmacotherapy a pathophysiologic approach. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. pp. 1333–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–7. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC index with DDDs. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Preventability in reporting adverse drug reactions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vengurlekar S, Shukla P, Patidar P, Bafna R, Jain S. Prescribing pattern of antidiabetic drugs in Indore city hospital. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:637–40. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.45404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willey CJ, Andrade SE, Cohen J, Fuller JC, Gurwitz JH. Polypharmacy with oral antidiabetic agents: An indicator of poor glycemic control. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:435–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bocuzzi JS, Wogen J, Fox J, Sung CY, Shah BA, Kim J. Utilization of oral hypoglycemic agents in drug-insured US population. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1411–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sultana G, Kapur P, Aqil M, Alam MS, Pillai KK. Drug utilization of oral hypoglycemic agents in a university teaching hospital in India. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35:267–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu SY, Lung BC, Chang S, Lee SC, Critchley JA, Chan JC. Evaluation of drug usage and expenditure in a hospital diabetes clinic. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1998;23:49–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1998.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upadhyay DK, Palaian S, Ravi Shankar P, Mishra P, Sah AK. Prescribing pattern in diabetic outpatients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2007;4:248–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P. Treatment of hypertension in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:134–47. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau GS, Chan JS, Chu PL, Tse DC, Critchely JA. Use of antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs in hospital and outpatient settings in Hong Kong. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30:232–7. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson J, Lindberg G, Gottstater M. Difference in pharmacotherapy and in glucose control of type 2 diabetes patients in two neighbouring towns: A longitudinal population-based study. Diabetes Obese Metab. 2001;3:249–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2001.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Texas diabetes council [Online] [Last cited on 2010 Aug 22]. Available from: http://www.texasdiabetescouncil.org .

- 17.Wulffele GM, Kooy A, Lehert P, Bets D, Ogterop JC, Burg BB. Combination of insulin and metformin in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2133–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes SG. Prescribing for the elderly patients: Why do we need to exercise caution? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:531–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutsky EA, McDaniel HG, Tharpe DL, Alred G, Pek S. Spontaneous hypoglycemia in renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:1364–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]