Abstract

Background:

The objective of this study was to assess the results of the pulmonary artery (PA) banding in patients with congenital heart defects (CHD) and pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the current era.

Methods:

We analyzed data from 305 patients who underwent PA banding between April 2005 and April 2010 at our centre. All patients were approached through a left thoracotomy. Twenty percent of patients underwent PA banding based on Trusler's rule (Group 1), 55% of them underwent PA banding based on PA pressure measurement (Group 2), and the rest of them (25%) based on surgeon experience (Group 3). The follow-up period was 39 ± 20 month and 75% of patients (230 cases) had definitive repair at mean interval 23 ± 10 months.

Results:

The rate of anatomically and functionally effectiveness of PA banding in all groups was high (97% and 92%, respectively). There were no significant differences in anatomically and functionally efficacy rate between all groups (P=0.77, P=0.728, respectively). There was PA bifurcation stenosis in six cases (2%), and pulmonary valve injury in one case (0.3%). The mortality rate in PA banding was 2% and in definitive repair was 3%.

Conclusions:

We believe that PA banding still plays a role in management of patients with CHD, particularly for infants with medical problems such as sepsis, low body weight, intracranial hemorrhage and associated non cardiac anomalies. PA banding can be done safely with low morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, pulmonary artery banding, pulmonary hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Muller and Dammann[1] introduced pulmonary artery banding (PA banding) in clinical practice in 1951. They advocated this operation for patients with single ventricle or large ventricular septal defect (VSD). Since then, this operation has been used as a palliative procedure for small infants with complex congenital heart defects.[2,3] Currently, early primary repair is the treatment of first choice for congenital cardiac defects.[4,5]

The objective of this study was to assess the result of PA banding in patients with congenital heart defects and to analyze if PA banding still plays an important role in the treatment of congenital heart disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this retrospective study, all patients who underwent PA banding between April 2005 and April 2010 in Rajaee Heart Center were evaluated.

Data including age, diagnosis, weight, sex, primary type of procedure for PA banding, early and late complications, rate of anatomically and functionally effectiveness of PA banding, peak systolic and mean systolic gradient after PA banding during operation and echo in intensive care unit (ICU) in the post operative period. Echo was done 4–6 h post op (intubated patient) and first day post op eration in ICU (extubated patient) and 4–6 days after op eration or before discharge and after one month in clinic and every 3 monthly in follow-up period until second surgery.

Early and late mortality rate, cause of death, complications after PA banding in final corrections and follow-up period were extracted and analyzed.

Anatomically effectiveness was defined as a 50% reduction in the diameter of pulmonary artery (PA) and functionally effectiveness was defined as PA systolic pressure less than 50% of systemic systolic pressure.

Surgical procedure

All patients were approached through a left lateral thoracotomy and a 4 mm wide polyester tape was used for all patients.

Some surgeons used Trusler's rule for achieving optimal PA banding (Trusler's rule group or group 1).[6] According to Trusler's rule, band was marked to a length of 20 mm, plus the number of millimeters corresponding to the child's weight in Kilograms, to indicate the ultimate tightness of the band. If the banding was done for a complex cardiac anomaly with bidirectional shunting, the length was 24 mm plus the child's weight.

For achieving optimal PA banding, some surgeons judged by the pressure difference across the band during the operation.

They did it based on measurements of the pulmonary artery pressure distal to the band.

In this group (PA pressure measurement or Group 2), the PA pressure was reduced to less than 50% of systolic pressure.[5]

The rest of patients underwent PA banding based on surgeon experience.

They did not use Trusler's rule, or PA pressure measurement (experience group or Group 3).

In all of the patients arterial oxygen saturation was considered and most of them had the arterial oxygen saturation more than 80% to 85% with FIO2 of 50%. When the ideal diameter is obtained, the band was fixed to pulmonary artery trunk adventitia to prevent migration of the band.

Data were analyzed with t-test and Chi-square test and the P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In this retrospective study, the data of 305 patients who underwent PA banding in Rajaee Heart Center from April 2005 to April 2010 were collected.

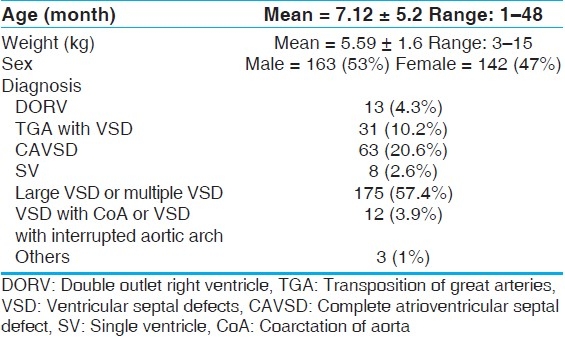

The mean age was 7.12 ± 5.2 month and the mean weight was 5.59 ± 1.6 kg. One hundred sixty three patients were male (53%) and 142 patients were female (47%). The preoperative demographic data of patients are depicted in Table 1, and Table 1 also shows the primary diagnosis of patients.

Table 1.

The preoperative demographic and diagnosis data of patients

One hundred seventy five patients had large ventricular septal defect (VSD) or multiple VSD (57.4%) and 63 patients had complete atrioventricular septal defect (CAVcD) (20.6%).

Other cardiac anomalies were the transposition of great arteries (TGA) with VSD (10.2%), double outlet right ventricle (DORV) (4.3%), VSD with coarctation of aorta or interrupted aortic arch (3.9%), single ventricular (SV) (2.6%).

Sixty-two patients (20%) underwent PA banding with Trusler's rule (Group 1) and 169 patients (55%) underwent PA banding based on measurement of the PA pressure distal the band during the operation (Group 2) and the rest of patients (72 cases, 25%) underwent PA banding based on surgeon experience (Group 3).

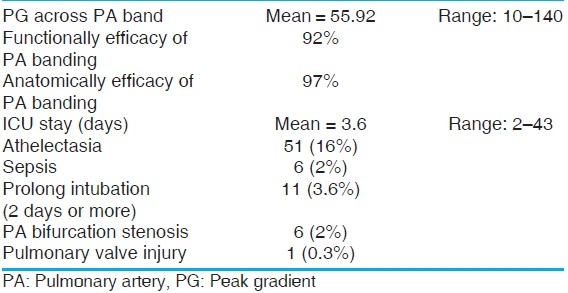

In the postop echocardiography 97% of the PA banding were anatomically and 92% of them were functionally effective. The mean peak gradient (PG) across PA banding was 56 ± 18 mmHg. There were no significant differences in anatomically effectiveness rate between different type of PA banding (Group 1, 2, and 3) (P=0.77%) and functionally effectiveness rate between all groups (P=0.728).

There were 51 cases of postoperative atelectasia (16%) and six cases of the sepsis and 11 cases of the prolong intubation (intubation period 2 days and/or more) (3.6%). No case of bleeding and PA injury during operation were found. The postoperation data and character of patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The postoperative data and characters of patients

The follow-up period was 39 ± 20 months. The in-hospital mortality was 2% (six cases) and three case of them died due to sepsis and another died due to heart failure. No patient died during follow up period.

Two hundred and three patients (75.4%) had definitive repair of a mean interval 23 ± 10 months. The mean age at definitive repair was 30.48 ± 11 months and the mean weight was 11 ± 2.6 kg.

Two percent of patients had PA bifurcation stenosis (six cases) and one patient (0.3%) had pulmonary valve injured. In hospital mortality rate in definitive repair was 3% (seven cases).

In definitive repair, only 20% of patients underwent pulmonary artery repairing with pericardial patch after PA de-banding and the rest of patients (80%) underwent just PA de-banding without any repair of pulmonary artery.

There were residual pulmonary stenosis (PS) in 2% of patients after definitive repairing with mean gradient of 30 mmHg. There were no significant differences in residual PS after PA de-banding and repairing, with pericardial patch and without pericardial patch.

DISCUSSION

We know that primary repair is expected to replace staged operation.[2–5] We resorted to PA band in the interest of safety, and our results are relevant to developing centers with suboptimal infrastructure for the care of infants. The interval mortality was not there and the results of definitive surgery was acceptable. If the definitive surgery had been undertaken at a younger age, the mortality could have been higher. With improvement in infrastructure, we are also moving towards primary correction. However, the two-stage strategy has proven well for our patients. Further, in patients unlikely to tolerate cardiopulmonary bypass, sepsis, very poor weight, or complex heart disease PA band is less controversial. Such patients contributed 45% of our patients. Twenty percent of our patients weighed less than 4 kg and 20% of patients had complex heart disease and sepsis before operation.

In our study the mortality rate of PA banding was 2% (six cases), but mortality rate in other studies reported between 10% to 38%.[2–5] The reported mortality rate decreased from approximately 30% before 1980 to approximately 10%.[7–9]

In the series reported by Takayama et al., mortality rate was 13.8%.[2] In our study, multivariate analysis demonstrated that no isolated variable including sex, weight and diagnosis were significant risk factors. But in some reports, child's weight was detected as a significant risk factor for early death.[3]

The complications of banding include distal migration of band and erosion of band into the PA lumen.[2,3] We had bifurcation stenosis in 2% of our patients and we didn’t have any erosion of band into the PA lumen and we also did not have bleeding and rupture of PA in our series.

Despite differences in the way the PA banding was done; the results were similar in three groups, although PA pressure might have been higher in group 2 theoretically. The management of PA band in the definitive repair stage was mostly only debanding.

The financial, psychological stress of two operations, we believe was counter balanced by safety gained.

PA banding still plays an important role in the treatment of functionally single ventricle.[3,4,10,11] In these patients, PA banding is as an initial step followed by bidirectional cava pulmonary shunts. About de-banding of PA in definitive repair, we believe that in most of patients the removal of band without repairing PA could be enough and the rate of residual PS in our series was low (2%).

CONCLUSIONS

We believe that PA banding still plays a role in management of patient with congenital heart disease, particularly for infants with a single ventricle and infants with medical problems such as intracranial hemorrhage, low body weight, sepsis and associated noncardiac anomalies. We believe that PA banding can be done safely with low complications and mortality.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muller WH, Jr, Dammann JE. Treatment of certain congenital malformations of the heart by the certain of pulmonic stenosis to reduce pulmonary hypertension and excessive pulmonary blood flow: A preliminary report. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;95:213–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshimura N, Yamaguchi M, Oka S, Yoshida M, Murakami H. Pulmonary artery banding still has an important role in the treatment of the congenital heart disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1463. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takayama H, Sekiguchi A, Chikada M, Noma M, Ishizawa A, Takamato S. Mortality of pulmonary artery banding in the current era: Recent mortality of PA banding. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1219–24. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Günter T, Mazzitelli D, Haehnel CJ, Holper K, Sebening F, Meisner H. Long Term results after repair of complete atrioventricular defect: Analysis of risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:754–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouchouks NT, Blackstone EH, Doty DB, Hanley FL, Karp RB. Tricuspid atresia and management of single ventricle physiology. In: Kirklin, Barratt-Boyes, editors. Cardiac Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. pp. 1114–66. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trusler's GA, Mustard WT. A method of banding the pulmonary artery for large isolated ventricular septal defect with and without transposition of great arteries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1972;13:351–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64866-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kron IL, Nolan SP, Flanagan TL, Gutgessell HP, Muller WH., Jr Pulmonary artery banding revisited. Ann Surg. 1989;209:642–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198905000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horowitz MD, Culpepper WS, 3rd, Williams LC, 3rd, Sundgaard-Riise K, Ochsner JL. Pulmonary artery banding: Analysis of a 25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48:444–50. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Blanc JG, Ashmor PG, Pineda E, Sander GC, Patterson MW, Tipple M. Pulmonary artery banding: Results and current indications in pediatric cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44:628–32. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metton O, Gaudin R, Ou P, Gerelli S, Mussa S, Sidi D, et al. Early prophylactic pulmonary artery banding in isolated congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:728–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kajihara N, Asou T, Takeda Y, Kosaka Y, Onakatomi Y, Nagafuchi H, et al. Pulmonary artery banding for functionally single ventricles: Impact of tighter banding in staged Fontan era. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:174–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]