Abstract

Background:

Paravertebral block (PVB) is useful for post-operative analgesia after breast surgery. Bupivacaine is used for PVB at higher concentrations (0.5%), which may lead to systemic toxicity after absorption. Therefore, we proposed to evaluate the efficacy of lower concentrations of bupivacaine with and without fentanyl for thoracic PVB in patients undergoing surgery for carcinoma breast.

Methods:

Forty-eight patients scheduled for surgery for breast cancer were enrolled in this prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial and were allocated to one of four groups: 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/ ml, 0.25% bupivacaine + epinephrine 5 mcg/ ml with 2 mcg/ml fentanyl, 0.5% bupivacaine + epinephrine 5 mcg/ml or isotonic saline. PVB was performed and 0.3 ml/kg of the test drug was administered before induction of general anaesthesia. The primary outcome assessed was post-operative analgesic requirement for a period of 24 h. Secondary outcome measures were post-operative pain scores at rest and on movement of the arm, latency to first opioid, post-operative nausea and vomiting, quality of sleep, ability to move arm and patient satisfaction.

Results:

The patient characteristics and anaesthetic technique were comparable among the groups. The rescue analgesic consumption as well as cumulative pain scores at rest and on movement were significantly less in 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine with fentanyl and 0.5% bupivacaine+epinephrine groups (P<0.05). The average duration of analgesia was found to be 18 h after either 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine+fentanyl or 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Conclusions:

Lower concentrations of bupivacaine can be combined with fentanyl to achieve analgesic efficacy similar to bupivacaine at higher concentrations, decreasing the risk of toxicity in PVB.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, fentanyl, mastectomy, paravertebral block, post-op analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic paravertebral block (PVB) is used for pain relief after thoracotomy[1,2] and mastectomy.[3–6] Breast surgery for malignancy is usually performed under general anaesthesia, and is associated with considerable post-operative pain, nausea and vomiting (PONV).[7] Of the various local and regional anaesthetic techniques evaluated in the past to reduce post-operative pain after breast surgery,[8–10] thoracic PVB appears promising due to reduction in post-operative pain, decreased opioid consumption with reduction in PONV, drowsiness, risk of respiratory depression and cost saving.[11,12] Additional advantages reported include decrease in the incidence of chronic post-surgical pain and improvement in subcutaneous oxygenation in the wound site thus possibly reducing infection risk and improving wound healing.[13]

The most commonly used agent for PVB has been 0.5% bupivacaine, and has the risk of systemic toxicity when administered in large doses.[14] Adjuvants like fentanyl or clonidine improved the quality of blockade; however, they are associated with hypotension and nausea.[15] Continuous infusion of lower concentrations of local anaesthetics decreases the risk of systemic toxicity.[16] Therefore, we undertook a prospective trial to study the efficacy of a single bolus injection of lower concentration of bupivacaine with and without fentanyl and compare it with 0.5% bupivacaine for thoracic PVB.

METHODS

After obtaining approval from the Hospital Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent, 48 ASA 1 and 2 patients scheduled for total mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection were enrolled from June 2008 to July 2009. The exclusion criteria were local infection, anatomic deformities of the spine, coagulation disorders, morbid obesity (body mass index >35 kg/m 2), allergy to local anaesthetics, patient refusal, severe respiratory or cardiac disorders, pre-existing neurological deficits, liver or renal insufficiency, pregnancy or breast feeding and breast reconstruction surgery.

During the pre-anaesthetic assessment, informed consent was obtained and patients were educated about reporting pain on the 11-point verbal rating scale (VRS),[17] where 0=no pain and 10=worst imaginable pain. Oral diazepam 0.1 mg/kg was administered the night before and on the morning of surgery. Before induction of anaesthesia, all patients received PVB and were assigned to one of the four groups of 12 each using a computer-generated random number assignment in sealed opaque envelopes – 0.25% bupivacaine+ epinephrine 5 μg/ml (Group B.25), 0.25% bupivacaine+ epinephrine 5 μg/ml+fentanyl 2 μg/ml (Group FB.25), 0.5% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml (Group B.5) and normal saline (Group NS).

On arrival to the operating room, monitoring lines were established for non-invasive blood pressure measurements, continuous electrocardiography and pulse oximetry. The patients were sedated with midazolam 1 mg i.v. They were placed in the lateral position with the side to be blocked and operated uppermost. A 26-gauge needle was inserted 2.5 cm lateral to the T3 spine and skin, subcutaneous tissue and periosteum of the transverse process were anaesthetized with 2–5 ml of lignocaine 10 mg/ml. The PVB was performed with an 18-gauge Tuohy needle using the loss-of-resistance technique, seeking contact with the lateral process of T3 as a landmark before advancing the needle into the paravertebral space. 0.3 ml/kg of the drug/normal saline was injected into the paravertebral space according to assignment. A staff anaesthesiologist not involved in the management of the patient or study prepared the injectate according to randomization. The patients and all staff involved in patient management and data collection were unaware of the group assignment.

The patients were turned supine to induce general anaesthesia with fentanyl 1 μg/kg i.v. and propofol 2–3 mg/kg followed by vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Anaesthesia was maintained with propofol infusion 100–200 μg/kg/min. Additional boluses of fentanyl 0.5 μg/kg i.v. were given if heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) increased more than 20% from the pre-operative baseline. At the end of surgery, neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg and the trachea was extubated on return of consciousness. Intraoperative monitoring included continuous electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry and non-invasive blood pressure measurement every 5 min.

After emergence from anaesthesia, the patients were transferred to the post-op recovery room where pain was assessed by a blinded observer both at rest and on movement of the shoulder using VRS. Assessments were carried out every 5 min till 30 min and subsequently at 60 min, 90 min, 120 min, 4 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h and 24 h. Analgesia in the recovery room was provided by i.v. morphine 0.05 mg/kg boluses to maintain VRS<3. PONV was assessed on a 3-point scale (ref), where 0=no nausea, no vomiting; 1=nausea present, no vomiting; 2=vomiting present with or without nausea. Injection of ondansetron 0.15 mg/kg was administered if the PONV score was ≥1. At the end of 24 h, patient satisfaction was assessed with the Numerical Rating scale (NRS) (0=dissatisfied and 10=most satisfied) and quality of overnight sleep on a 3-point scale (0=no sleep, 1=intermittently disturbed sleep, 2=good sleep).

Sample size was calculated based on a pilot study, which indicated that the mean±SD 24-h consumption of morphine following mastectomy under general anaesthesia was 15±8 mg. Administration of PVB is associated with 75% reduction in the 24-h consumption of morphine.[18] Twelve patients were required in each group to demonstrate this difference, with type 1 error of 0.05 and type 2 error of 0.1.

The parametric data are expressed as mean (SD) and analysed using one-way analysis of variance. The non-parametric data are expressed as median (IQR) and analysed using the Kruskal Wallis test. Further comparisons between the groups were done by the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kaplan Meir survival graph was used to analyse the post-operative pain-free interval. All analyses were performed using SPSS v13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and a P value <0.05 was taken to be significant.

RESULTS

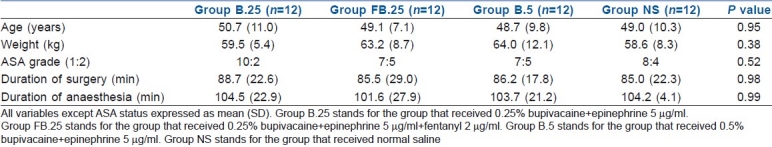

All the 48 enrolled patients completed the study protocol. The patient characteristics and intraoperative haemodynamic parameters were similar in the four groups [Table 1]. The requirement of additional fentanyl intraoperatively was significantly less in the 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine+fentanyl and the 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine groups (P=0.001) when compared with placebo [Table 2]. The heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressures were comparable between the four groups intraoperatively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Table 2.

Intra- and post-operative analgesia and side-effects

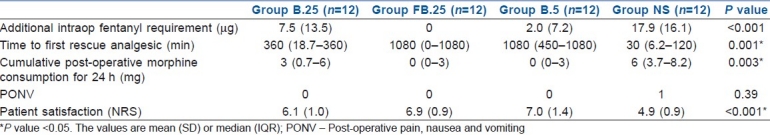

The number of patients who received morphine in groups FB.25 and B.5 were significantly less during the initial 12 h post-op [Figure 1]. This corroborates the finding of median interval to first analgesic of 18 h in these two groups, indicating significantly longer duration of post-operative analgesia (P=0.001) [Table 2]. In group B.25, more patients required rescue morphine between 4 and 12 h post-operatively, and this corresponds to median interval to first analgesic of 6 h. Rescue analgesic was required as early as 30 min in the control group.

Figure 1.

Requirement of morphine post operatively * indicates P value <0.05. Group B.25 stands for the group that received 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml. Group FB.25 stands for the group that received 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml+fentanyl 2 μg/ml. Group B.5 stands for the group that received 0.5% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml. Group NS stands for the group that received normal saline

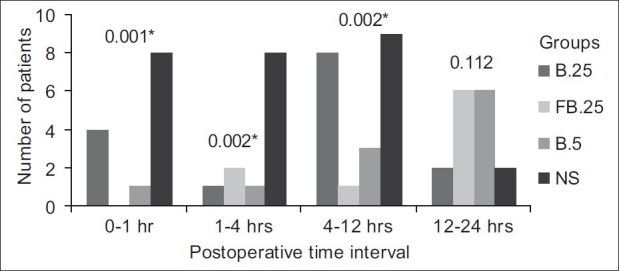

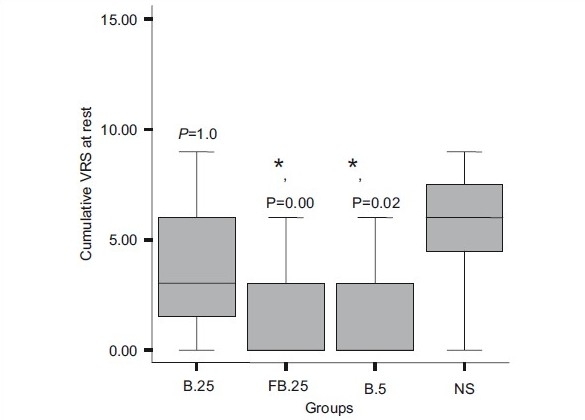

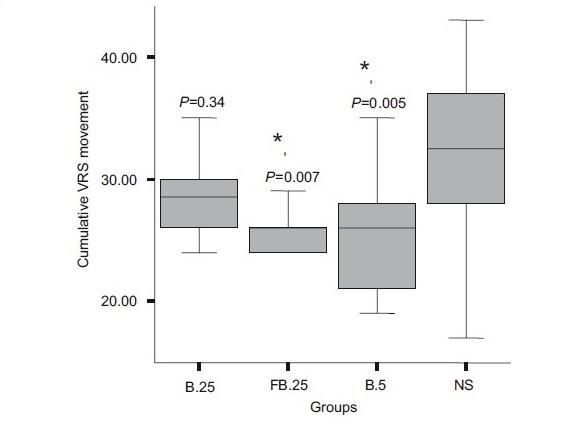

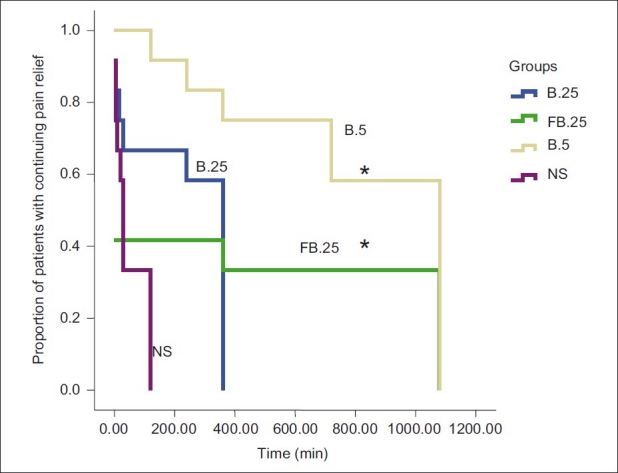

The cumulative rescue analgesic consumption in the first 24 h was significantly less in groups FB.25 and B.5 compared with groups B.25 and NS (P=0.003) [Table 2]. On comparing the groups, the requirements of additional intraop fentanyl and post-op morphine were similar in groups FB.25 and B.5. Similarly, the cumulative VRS scores (sum of all VRS scores) at rest and movement for 24 h post-operative were significantly lower in groups FB.25 and B.5 than in groups B.25 and NS (P<0.001 and P=0.003, respectively) [Figure 2a and b]. The number of patients with longer pain relief was higher in groups FB.25 and B.5 compared with groups B.25 and NS on the log-rank test (P<0.001) [Figure 3].

Figure 2a.

Cumulative pain scores for 24 h at rest. The line within each box indicates the median. The lower and upper limits of the box are the 25th and 75th centiles. The lines extending above and below the box are the 10th and 90th centiles. *P<0.05

Figure 2b.

Cumulative pain scores (24 h) with movement. The line within each box indicates the median. The lower and upper limits of the box are the 25th and 75th centiles. The lines extending above and below the box are the 10th and 90th centiles. *P<0.05. Group B.25 stands for the group that received 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml. Group FB.25 stands for the group that received 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml+fentanyl 2 μg/ml. Group B.5 stands for the group that received 0.5% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml. Group NS stands for the group that received normal saline

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meir analysis showing the proportion of patients in each group with continuing pain relief until the administration of first rescue analgesic. * P value <0.001. Group B.25 stands for the group that received 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml. Group FB.25 stands for the group that received 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml+fentanyl 2 μg/ml. Group B.5 stands for the group that received 0.5% bupivacaine+epinephrine 5 μg/ml. Group NS stands for the group that received normal saline

There was no incidence of nausea or vomiting in the post-operative period in groups B.25, FB.25 and B.5. One patient experienced nausea in group NS. No complication possibly associated with PVB, such as pain or soreness at injection site, hypotension, interpleural injection, pneumothorax or dural puncture, was encountered. The quality of overnight sleep and overall patient satisfaction were significantly better in groups FB.25 and B.5 (P=0.036 and P<0.001, respectively), correlating to the duration of analgesia in these two groups.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study, we have demonstrated that patients who receive PVB with 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine+fentanyl or 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine in addition to general anaesthesia experience significantly better post-operative analgesia as compared with PVB with 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine and general anaesthesia or general anaesthesia alone. Cumulative rescue analgesic consumption in the first 24 h was significantly lower in the 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine+fentanyl and 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine groups compared with the 0.25% bupivacaine+epinephrine and control groups (P=0.003). Earlier investigators[12,15,18] have also observed a similar efficacy of PVB for breast carcinoma surgery.

We have been able to highlight the utility of fentanyl 2 μg/ml as an adjuvant in PVB. The addition of fentanyl to a lower concentration (0.25%) of bupivacaine provided similar post-operative analgesia as 0.5% bupivacaine. Fentanyl administered through the paravertebral route may contribute to analgesia by acting on opioid receptors found in the dorsal root ganglia structures.[19] Barlacu et al.[15] used levobupivacaine with fentanyl 4 μg/ml infusion for post-operative analgesia paravertebrally, and reported that patients experienced side-effects like nausea and pruritus. They had suggested that further work is required to determine the lowest effective dose of fentanyl. When plasma concentrations of levobupivacaine, fentanyl 2 μg/ml and clonidine were analysed following PVB during breast surgery, it was found that plasma levels of levobupivacaine were within the safe range, and plasma levels of fentanyl and clonidine were less than the effective levels after IV administration, suggesting that their analgesic effect may be partly attributed to a peripheral mechanism of action.[20] In view of the increased incidence of side-effects with 4 μg/ml, we used fentanyl in a concentration of 2 μg/ml, and observed that the incidence of nausea and vomiting were similar to patients where fentanyl was not used.

As effective analgesia/anaesthesia with PVB using single-level injection requires a large volume, decreasing the concentration of the local anaesthetic agent would confer increased safety as the risk of systemic toxicity is reduced by decreasing the total dose used. There are reports of adverse sequelae such as convulsions when bupivacaine was used in higher concentration in larger volume.[12] Kairaluoma et al.,[12] who used 0.5% bupivacaine in PVB, had measured plasma concentrations of bupivacaine and reported that there was great interindividual variation in the total plasma concentrations of bupivacaine. The highest mean plasma bupivacaine concentration of 750 ng/ml occurred 20 min after injection. In this series, one patient developed seizures when a total dose of 120 mg of 0.5% bupivacaine was injected.

We had hypothesized that use of lower concentration of bupivacaine (0.25%) may result in lower plasma levels and, thus, offer better margin of safety. However, lower concentrations and thus lower doses may have a shorter duration of analgesia compared with 0.5% bupivacaine, which is confirmed by our findings in Group B.25. We had proposed to overcome this limitation by the addition of fentanyl 2 μg/ml to 0.25% bupivacaine. The results demonstrate that analgesic consumption, pain scores and duration of analgesia were comparable between patients who received PVB with 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.25% bupivacaine+fentanyl.

Whether a multilevel injection of PVB (at C7-T6 or C7-T7) is superior to a single-injection technique for breast resection has not been evaluated. Published results on pain and recovery are quite similar. Although the incidences of pneumothorax and intravascular injection in PVBs are small, we find it logical to perceive that the risk of complications per patient increases when multiple injections are performed. Therefore, single-level thoracic PVB was used in our study design. However, it can be argued that single-level injection may lead to variable spread of the drug and also has a higher potential for inadvertent intravascular injection and systemic toxicity.

PONV in our study population was infrequent. The anti-emetic property of propofol used for induction of anaesthesia and administration of prophylactic ondansetron in our study may have contributed to this low incidence. One of the limitations of our study is that objective documentation of failure or adequacy of block using loss of perception to thermal stimuli or pin prick was not attempted. Also, the difference in serum concentrations of bupivacaine between PVB administered using 0.25% bupivacaine and 0.5% bupivacaine was not measured.

CONCLUSION

Bupivacaine 0.25%+epinephrine combined with fentanyl 2 μg/ml provides excellent post-operative analgesia comparable to bupivacaine 0.5%+epinephrine, with the advantage of a lesser toxicity profile when used for single-level thoracic PVB for breast surgery.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Richardson J, Sabanathan S, Mearns AJ, Shah RD, Goulden C. A prospective, randomized comparison of interpleural and paravertebral analgesia in thoracic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:405–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson J, Sabanathan S, Jones J, Shah RD, Cheema S, Mearns AJ. A prospective, randomized comparison of preoperative and continuous balanced epidural or paravertebral bupivacaine on post-thoracotomy pain, pulmonary function and stress responses. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83:387–92. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coveney E, Weltz CR, Greengrass R, Iglehart JD, Leight GS, Steele SM, et al. Use of paravertebral block anesthesia in the surgical management of breast cancer: Experience in 156 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:496–501. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weltz CR, Greengrass RA, Lyerly HK. Ambulatory surgical management of breast carcinoma using paravertebral block. Ann Surg. 1995;222:19–26. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moller JF, Lone N, Rodt SA, Ronning H, Carlsson PS. Thoracic paravertebral block for breast cancer surgery: A randomized double blinded study. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1848–51. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000286135.21333.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mcelwain J, Freir NM, Barlacu CL, Moriarty DC, Sessler DI, Buggy DJ. Feasibility of patient controlled paravertebral analgesia for major breast cancer surgery: A prospective randomized double blind comparison of two regimens. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:665–8. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b7f01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaffe SM, Campbell P, Bellman M, Baildam A. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in women following breast surgery: An audit. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000;17:261–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.2000.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang T, Parks DH, Lewis SR. Outpatient breast surgery under intercostal block anaesthesia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:299–303. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fassoulaki A. Brachial plexus block for pain relief after modified radical mastectomy. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:986–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch E, Welch K, Carabuena J, Eberlein T. Thoracic epidural anaesthesia improves the outcome after breast surgery. Ann Surg. 1995;222:663–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199511000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert J, Hultman J. Thoracic paravertebral block: A method of pain control. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1989;33:142–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1989.tb02877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kairaluoma PM, Bachmann MS, Korpinen AK, Rosenberg PH, Pere PJ. Single-injection paravertebral block before general anesthesia enhances analgesia after breast cancer surgery with and without associated lymph node biopsy. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1837–43. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136775.15566.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buggy DJ, Kerin MJ. Paravertebral analgesia with levobupivacaine increases postoperative flap tissue oxygen tension after immediate latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction compared with intravenous opioid analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:375–80. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200402000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson DS, Panian S, Kendall V, Maher DP, Peters G. Pain control after thoracotomy: Bupivacaine versus lidocaine in continuous extrapleural intercostal nerve blockade. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:825–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlacu CL, Frizelle HP, Moriaty DC, Buggy DJ. Fentanyl and clonidine as adjunctive analgesics with levobupivacaine in paravertebral analgesia for breast surgery. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:932–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iohom G, Abdalla H, Brein J, Szarvas S, Larney V, Buckley E. The associations between severity of early postoperative pain, chronic post-surgical pain and plasma concentrations of stable nitric oxide products after breast surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:995–1000. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000240415.49180.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SN, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Breivik HE, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein SM, Bergh A, Steele SM, Georgiade GS, Greengrass RA. Thoracic paravertebral block for breast surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1402–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200006000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickenson AH. Spinal cord pharmacology of pain. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:193–200. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burlacu CL, Frizelle HP, Moriarty DC, Buggy DJ. Pharmacokinetics of levobupivacaine, fentanyl, and clonidine after administration in thoracic paravertebral analgesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]