Abstract

Auxin/indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plays a major role in growth responses to developmental and genetic signals as well as to environmental stimuli. Knowledge of its regulation, however, remains rudimentary, and few proteins acting as transcriptional modulators of auxin biosynthesis have been identified. We have previously shown that alteration in the expression level of the SHORT INTERNODES/STYLISH (SHI/STY) family member STY1 affects IAA biosynthesis rates and IAA levels and that STY1 acts as a transcriptional activator of genes encoding auxin biosynthesis enzymes. Here, we have analyzed the upstream regulation of SHI/STY family members to gain further insight into transcriptional regulation of auxin biosynthesis. We attempted to modulate the normal expression pattern of STY1 by mutating a putative regulatory element, a GCC box, located in the proximal promoter region and conserved in most SHI/STY genes in Arabidopsis. Mutations in the GCC box abolish expression in aerial organs of the adult plant. We also show that induction of the transcriptional activator DORNRÖSCHEN-LIKE (DRNL) activates the transcription of STY1 and other SHI/STY family members and that this activation is dependent on a functional GCC box. Additionally, STY1 expression in the strong drnl-2 mutant or the drn drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutant, carrying knockdown mutations in both DRNL and its close paralogue DRN as well as one of their closest homologs, PUCHI, was significantly reduced, suggesting that DRNL regulates STY1 during normal plant development and that several other genes might have redundant functions.

The key elements in auxin-mediated development in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) are auxin biosynthesis and active polar transport, which are required to produce and maintain auxin gradients and maxima (for review, see Feraru and Friml, 2008; Chandler, 2009; Zhao, 2010). In a recent model for explaining pattern formation and morphogenesis in roots, Grieneisen et al. (2007) suggested that auxin transport overrides the effects of changes in auxin biosynthesis. However, mutants with deficiencies in auxin biosynthesis show severe defects in vegetative and reproductive development (Cheng et al., 2006, 2007; Stepanova et al., 2008; Tao et al., 2008), indicating that not only auxin redistribution but also local auxin biosynthesis has a major impact on plant growth and development.

Several plant enzymes are rate limiting in auxin biosynthesis, each enzyme regulating one of the first steps in what is thought to be different Trp-dependent pathways, ultimately leading to the formation of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). The cytochrome P450 family members CYP79B2 and CYP79B3 have been shown to convert Trp to indole-3-acetaldoxime (Zhao et al., 2002; Ljung et al., 2005), an important metabolite for glucosinolate as well as IAA biosynthesis, TRP AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS1 (TAA1) and its two homologs TRP AMINOTRANSFERASE RELATED1 (TAR1) and TAR2 convert Trp to indole-3-pyruvic acid (Stepanova et al., 2008; Tao et al., 2008), and the YUCCA (YUC) family of flavin monooxygenases is reported to convert tryptamine to N-hydroxyl tryptamine (Zhao et al., 2001). The finding that other IAA biosynthesis pathways (e.g. YUC) cannot compensate for the loss of TAA1 suggests that these proteins are active at different spatial and temporal sites during the plant life cycle (Tao et al., 2008). Interestingly, recent reports suggest that TAA/TAR and YUC genes function in the same auxin biosynthetic pathway (Strader and Bartel, 2008; Phillips et al., 2011) and also question the biochemical function of YUC in the tryptamine pathway (Tivendale et al., 2010; Nonhebel et al., 2011), highlighting how little we actually know regarding these pathways.

We recently showed that SHORT INTERNODES/STYLISH (SHI/STY) family members are important throughout plant development and directly regulate YUC4-mediated auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Sohlberg et al., 2006; Ståldal et al., 2008; Eklund et al., 2010a), and we could show that transcription of YUC8 was activated by STY1 (Eklund et al., 2010a). This suggests that the temporal and spatial regulation of SHI/STY family members may be crucial for the developmental regulation of auxin production. Only limited information regarding upstream regulators directly controlling the activity of SHI/STY family genes is present, and although genetic data have indicated that the transcriptional corepressor LEUNIG may participate in the transcriptional regulation of SHI/STY family members (Kuusk et al., 2006; Ståldal et al., 2008), the molecular connections still await verification. Also, SWIRM domain PAO protein1/Lysine-Specific Demethylase1-LIKE1 has been suggested to fine-tune root elongation via transcriptional regulation of the SHI/STY family member LATERAL ROOT PRIMORDIUM1 (LRP1; Krichevsky et al., 2009). Other upstream regulators could be genes known to affect auxin homeostasis and/or organ formation. Furthermore, SHI-RELATED SEQUENCE5 (SRS5) has been shown to be activated by pathogen attack (Barcala et al., 2010), suggesting SHI/STY genes to have a function in stress responses.

Here, we have searched for putative upstream regulators by screening for common promoter elements in the highly redundant SHI/STY gene family members in Arabidopsis. We identified a putative GCC box (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1990) located within the promoter region 500 bp upstream of the translational start site in all but one family member in Arabidopsis. The putative GCC box is inverted and part of a 14- or 15-bp conserved region in five of the SHI/STY family promoters, strongly suggesting a conserved function for this element. The APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (AP2/ERF) domain is generally considered to be a GCC box-binding domain and is unique to members of the AP2/ERF superfamily, consisting of 147 putative transcription factors in Arabidopsis (Nakano et al., 2006). It has been shown that the N terminus of the AP2/ERF domain binds in a sequence-specific manner to GCC box elements (Hao et al., 1998). Our data indicate that a functional GCC box is required for the expression of SHI/STY family members in aerial IAA biosynthesis zones (i.e. in YUC gene expression domains). The SHI/STY family expression at other sites, such as the lateral root primordia, stem, and proximal part of cotyledons and mature leaves, is not affected by mutations in the GCC box and therefore is most likely regulated by other, yet unknown, mechanisms. We can also show that ectopic expression of the AP2/ERF family member DORNRÖSCHEN-LIKE (DRNL) activates the transcription of STY1 in a GCC box-dependent manner and that STY1 is down-regulated in the drnl-2 mutant as well as in the drn-1 drnl-1 puchi triple mutant, suggesting that several AP2/ERFs redundantly regulate STY1 during plant development.

RESULTS

The Arabidopsis SHI/STY Family Members Contain a Conserved Element Similar to a GCC Box

In order to identify conserved promoter motifs affecting the transcriptional activity of SHI/STY genes, we analyzed promoters, 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs), and intron sequences of the nine active SHI/STY family members in Arabidopsis (SHI, STY1 and -2, LRP1, and SRS3 to -7). Using the MEME (for Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation) software (Bailey and Elkan, 1994), we identified a short conserved promoter/5′ UTR element located only a few hundred bp upstream of the start codon of each of the STY1, STY2, SHI, SRS5, and SRS7 genes (Table I). The identified element with the core GGCGGC is similar to an inverted ethylene-responsive element (TAAGAGCCGCC; Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1990), usually referred to as a GCC box. The GCC box has been predicted to be a target for ethylene signaling pathways, because mutations in this element eliminated the ethylene responsiveness of a tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) chitinase gene (Shinshi et al., 1995). Later reports define the ERF-binding element of the GCC box as an (A)GCCGCC core in which nucleotides G-1, G-4, and C-6 exhibit the highest binding specificity to the ERFs (Hao et al., 1998; Fujimoto et al., 2000).

Table I. GCC-box-like sequences in SHI/STY family promoters.

| Gene | Sequence | Strand | Positiona |

| SHI | TGGCGGCGTTGCAG | + | −390 |

| STY1 | TGGCGGCGTTGCAG | + | −340 |

| STY2 | TGGCGGCGTTGCAG | + | −361 |

| SRS5 | TGGCGGCGTTTGCAG | + | −150 |

| SRS7 | TGGCGGCGTTTGCAG | + | −244 |

| OsSRS4 | TGGCGGCGTTTGCAG | + | −644 |

| LRP1 | CGGCGGCGACGGAG | + | −14 |

| SRS6 | CGGCGGCGACGGAG | − | −40 |

| OsSRS1 | GGCGGCGTCGG | + | −91 |

| OsSRS2 | CGGCGGCGGCGGA | + | −89 |

| SRS4 | CGGCCGCGTTGC | − | −97 |

| OsSRS3 | CGGCGGCGGCGGC | + | −146 |

| SRS3 | No match | ||

| OsSRS5 | No match |

First nucleotide of the element in relation to the translational start site (ATG). Bold nucleotides represent the conserved GCCGCC component.

The GCC box-like elements found in SHI/STY genes are conserved at positions G-1, G-4, and C-6, suggesting that they are bona fide GCC boxes, possibly recognized by proteins of the AP2/ERF family.

The annotated transcriptional start site (TSS) of STY1 and STY2 is located just downstream of the GCC box, while the annotated TSS in SHI is found upstream, indicating that the element is located in the UTR of SHI. There is no annotated TSS in SRS5 or SRS7. Shorter sequences with striking similarity to the GGCGGC component of the conserved sequence were found in the promoter or 5′ UTR of LRP1, SRS4, and SRS6 but not in SRS3 (Table I).

A phylogenetic analysis of conserved coding regions from all nine SHI/STY family genes in Arabidopsis showed that SHI/STY family members are separated into two major clades, one containing STY1, STY2, SHI, SRS3 to -5, and SRS7, whereas the other includes LRP1 and SRS6 (Kuusk et al., 2006). The three Selaginella moelendorffii and the two Physcomitrella patens SHI/STY homologs cluster with the LRP1/SRS6 genes (Eklund et al., 2010b). Several SHI/STY family members in Arabidopsis form evolutionarily closely related pairs, most likely originating from the last genome duplication event (Kuusk et al., 2006). SHI and STY1 form one such pair and SRS5 and SRS7 form another pair, closely related to the STY1/SHI pair. Thus, it is not surprising to find the conserved GCC box in the regulatory regions of these four genes. However, STY2 and SRS4 also form a pair, and the conserved element in STY2 is identical to that of SHI and STY1, while the element in SRS4 is inverted and rearranged (Table I). LRP1, SRS3, and SRS6 do not form any pairs (Kuusk et al., 2006); therefore, it is interesting that the 14-bp element in LRP1 is identical to that found inverted in SRS6 (Table I).

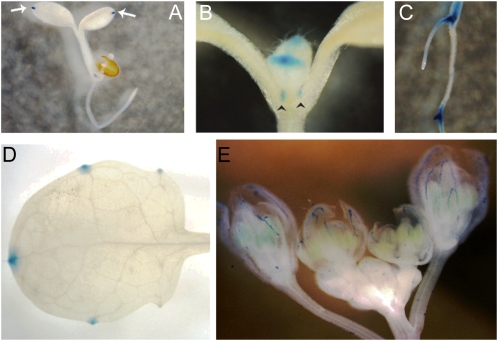

The spatial and temporal activities of STY1, STY2, SHI, and SRS5 during plant development have been studied in detail (Fridborg et al., 2001; Kuusk et al., 2002, 2006) and were found to be largely overlapping, with some minor exceptions. Using an enhancer/promoter trap approach, Smith and Fedoroff (1995) suggested that LRP1 expression is restricted to lateral root primordia, whereas phenotypic characterizations of multiple SHI/STY mutants carrying a mutation also in LRP1, together with real-time (RT)-PCR data, revealed that LRP1 is expressed at similar sites as STY1, STY2, SHI, and SRS5 also in Arabidopsis aerial tissues (Kuusk et al., 2006). Here, we have studied the expression of SRS4 using a two-component GUS-reporter approach (Fig. 1). SRS4pro>>GUS is expressed in cotyledon tips, leaf primordia, hydathodes, stipules, and lateral root primordia and weakly at the edges of petals and sepals, demonstrating that its activity largely overlaps with that of the SHI/STY genes studied previously. Kuusk et al. (2006) showed that mutations in SRS4 enhanced the leaf phenotype of sty1-1 sty2-1 and, to a limited extent, that of gynoecia, confirming that SRS4 is active in leaves and buds. Additionally, transcriptome analysis (Hruz et al., 2008) reveals low levels of SRS4 transcripts in floral organs. Because we have no detailed expression data for the remaining genes, we can only extrapolate their expression patterns from other data. Since mutation of LRP1 enhanced the gynoecium and leaf defects of sty1-1 sty2-1 (Kuusk et al., 2006), LRP1 appears to act redundantly at certain developmental stages with other SHI/STY family members and thus should have at least partially overlapping expression patterns with STY1, STY2, SHI, and SRS5 also in aerial organs. The identified mutations in SRS6 and SRS7 did not cause a complete loss of gene activity (Kuusk et al., 2006), which is why their developmental roles have been hard to elucidate. Coexpression analysis of SHI/STY family genes in different microarray experiments using ATTED-II (http://atted.jp) suggest that SHI, STY2, SRS5, and LRP1 are partly coregulated, whereas SRS4 and SRS6 are less tightly coexpressed with other SHI/STY genes. STY1, SRS3, and SRS7 were not included in the microarray analysis experiments. In summary, the available data from genetic and expression studies indicate that several SHI/STY family members could be partially coregulated, most likely by the same transcription factor or family of transcription factors.

Figure 1.

Expression of SRS4pro>>GUS largely overlaps with the expression of other SHI/STY family members. SRS4pro>>GUS is expressed in cotyledon tips (A; arrows), leaf primordium tips and stipules (B; arrowheads), lateral root primordia (C) as well as in the base of lateral roots and in the root vasculature, but not in the root tips, in hydathodes (D), and at the edges of petals and sepals (E).

GCC Boxes Are Only Found in SHI/STY Family Promoters of Angiosperms

We also used MEME to search for the conserved promoter/UTR elements in the two moss (P. patens), three lycophyte (S. moelendorffii), and five rice (Oryza sativa) SHI/STY homologs. Interestingly, promoters of the two P. patens SHI/STY orthologs PpSHI1 and PpSHI2 (Eklund et al., 2010b) were not found to possess GCC box-like sequences. Likewise, GCC box-like elements could not be found in the lycophyte SHI/STY genes (data not shown). Of the five rice SHI/STY genes OsSRS1 to OsSRS5 (Kuusk et al., 2006), OsSRS1, OsSRS2, and OsSRS4 cluster with STY1/2, SHI, and SRS3-5/7 (Kuusk et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2010) and carry GCC box-like elements (Table I), although only OsSRS4 has the conserved 15-bp element found in SRS5/7 (Table I). Since OsSRS1, OsSRS2, and OsSRS4 form a clade in the phylogram, and thus appear more closely related to each other than to any of the SHI/STY genes from Arabidopsis, it is quite likely that the 15-bp element has been rearranged in OsSRS1 and OsSRS2. OsSRS3 and OsSRS5 form a clade with LRP1 and SRS6 (Kuusk et al., 2006), although none of them has a GCC box similar to LRP1/SRS6. OsSRS3 appears to have a GCC repeat that potentially could function as a GCC box, whereas OsSRS5 does not contain a GCC box (Table I). Interestingly, OsSRS1 has a GCC box-like element similar to that of LRP1/SRS6.

This suggests that the GCC box-like element was present before the split of dicots and monocots and that this type of element may only be present in SHI/STY homologs of angiosperms.

The GCC Box-Containing Elements of STY1, SHI, STY2, SRS5, and SRS7 Are Unique to SHI/STY Genes

To analyze the genome-wide distribution of the GCC box-containing elements found in SHI/STY family promoters, we performed a Patmatch search in all Arabidopsis genes using 3-kb regions located upstream of the predicted TSS as well as coding regions, UTRs, and introns. The entire 14- to 15-bp element present in SHI/STY1/STY2/SRS5/SRS7 could not be detected in any other Arabidopsis gene. However, the 14-bp element of SRS6/LRP1 was found in six additional sites in the genome (Supplemental Table S1). None of the genes possibly regulated by the SRS6/LRP1-like element appear to have functions directly related to those of SHI/STY genes, or hormonal homeostasis in general, although the full range of biological functions controlled by SHI/STY genes has not yet been established.

The Putative GCC Box Is Important for the Regulation of SHI/STY Expression in Aerial Tissues during Plant Development

The conservation, position, and base pair composition of the putative GCC box in the SHI/STY promoters strongly suggest that it could be important for the regulation of SHI/STY gene activity. Therefore, we mutated the core sequence GGCGGC to AAAAAA in the STY1pro:GUS construct (Kuusk et al., 2002), creating a STY1mutpro:GUS fusion that was introduced into the accession Columbia (Col). All four independent transformants investigated showed the same spatial and temporal expression pattern.

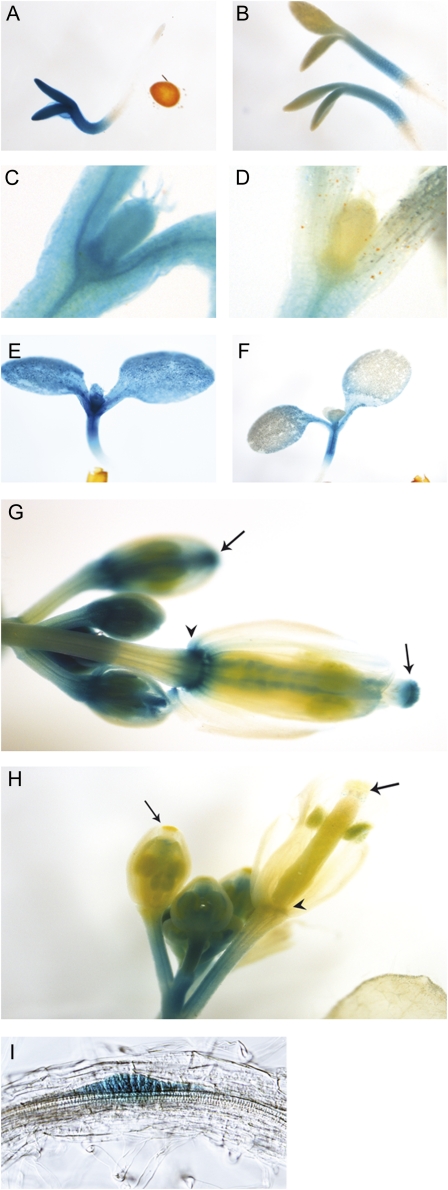

The expression pattern of STY1pro:GUS has previously been described in detail (Kuusk et al., 2002). In summary, STY1 is expressed in hypocotyls and cotyledons of young seedlings (Fig. 2, A and E), leaf primordia (Fig. 2, C and E), stipules, hydathodes, root tips, and lateral root primordia (Kuusk et al., 2002). STY1pro:GUS is also expressed in floral buds, sepals, styles, ovules, and receptacles (Fig. 2G). The expression of other SHI/STY family members coincides with that of STY1 in cotyledon tips, leaf primordia, lateral root primordia, receptacles, styles/stigmas, and hydathodes (Fridborg et al., 2001; Kuusk et al., 2002, 2006).

Figure 2.

STY1mutpro:GUS shows restriction in spatial activity compared with STY1pro:GUS. A and B, In 3-d-old seedlings, STY1pro:GUS (A) is active in hypocotyls and throughout the cotyledons, whereas STY1mutpro:GUS (B) shows residual activity only in hypocotyls and the proximal part of cotyledons. C to F, In 9- and 7-d-old-seedlings, STY1mutpro:GUS (D and F) activity remains in the hypocotyl and cotyledon petioles, whereas no STY1mutpro:GUS activity was found in leaf primordia although STY1pro:GUS is expressed at those sites (C and E). G and H, STY1mutpro:GUS is active in inflorescence stems of 28-d-old plants (H) but not in the apical tips of developing gynoecia (arrows), receptacles (arrowhead), or ovules, sites of very strong STY1pro:GUS activity (G). I, Lateral root primordium of STY1mutpro:GUS.

The GCC box mutation completely eliminated the strong STY1 expression in the distal parts of the cotyledon, including the cotyledon tip (Fig. 2, B and F), leaf primordia (Fig. 2, D and F), apical end of young gynoecia, style, stigma, ovule, and receptacle (Fig. 2H), suggesting that the GCC box is important for the majority of STY1 expression sites. However, signals were found in the hypocotyl, petiole, and proximal part of the cotyledon (Fig. 2, B, D, and F) as well as in lateral root primordia (Fig. 2I); therefore, STY1 expression in these tissues is considered to be GCC box independent.

STY1 Transcription Is Not Regulated by IAA or 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Levels

Because GCC boxes have been shown to be regulated by ERF proteins, we were interested in analyzing if the GCC box in SHI/STY genes responds to ethylene signaling. In microarray experiments in seedlings, only SRS4, but no other SHI/STY gene, was slightly up-regulated by 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) treatment (Genevestigator; Hruz et al., 2008). This indicates that at least SHI, STY2, LRP1, SRS5, and SRS6, which are spotted on the arrays, are not very sensitive to ethylene. In accordance, 4-d-old STY1pro:GUS seedlings treated with 10 μm ACC showed no altered GUS activity compared with nontreated seedlings (data not shown).

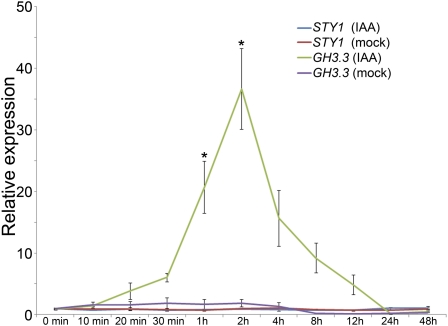

The transcription of some SHI/STY family members appears to be affected by exogenous auxin treatment in certain backgrounds (Genevestigator; Hruz et al., 2008), and in order to establish if the transcription of STY1 is controlled by auxin, we measured STY1 mRNA levels in Col seedlings treated with 5 μm IAA for 10 min to 48 h. This showed that STY1 expression in seedlings was not dramatically altered by exogenous IAA (Fig. 3) compared with the auxin-inducible gene GRETCHEN HAGEN3.3 (GH3.3; Hagen and Guilfoyle, 2002). However, STY1 was modestly but significantly (Student’s t test, P < 0.05) down-regulated at 2 h of IAA treatment (Fig. 3). This indicates that if auxin affects STY1 transcription, it is most likely as a repressor signal.

Figure 3.

STY1 gene activity in seedlings is not affected by exogenous IAA. qRT-PCR analysis of STY1 transcripts in wild-type (Col) seedlings after various incubation times of mock treatment and 5 μm IAA. The graph shows mean values of two biological replicates, and error bars indicate se. The GH3-3 gene served as a control for the IAA treatment. Stars denote significantly increased expression in IAA compared with mock treatments (Student’s t test, P < 0.05).

DRNL Can Activate the Transcription of SHI/STY Genes

Because several members of the AP2/ERF family have been shown to regulate GCC box-containing genes, we searched the literature for array experiments performed with the goal to identify downstream targets of individual AP2/ERF proteins. Interestingly, Ikeda et al. (2006) showed that SHI was significantly up-regulated (3.3 mean fold change) in root explants 1 h after the induction of constitutive expression of the AP2/ERF protein ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION2 (ESR2), previously named DRNL because of its high sequence identity to the Arabidopsis DRN protein (Kirch et al., 2003). As ESR2/DRNL was induced in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein synthesis, SHI was suggested to be a direct target of ESR2/DRNL (Ikeda et al., 2006). Marsch-Martinez et al. (2006) also studied downstream targets of ESR2/DRNL, although they called the protein BOLITA (BOL), and in a comparison of global gene expression in leaves of an ESR2/DRNL/BOL overexpressor line and the wild type, a 1.9- to 3-fold up-regulation of four of the nine SHI/STY family genes (SHI, STY2, SRS4, and LRP1) was revealed. ESR2/DRNL/BOL belongs to group VIII of the ERF/B subfamily in the AP2/ERF superfamily (Nakano et al., 2006). The ESR2/DRNL/BOL paralogue, DRN, has a very similar DNA-binding domain to that of ESR2/DRNL/BOL and has been shown to specifically bind GCC motif sequences in vitro (Banno et al., 2006). Furthermore, DRN was recently shown to target a GCC box in a transient in vivo assay (Matsuo and Banno, 2008), making ESR2/DRNL/BOL an interesting candidate to potentially regulate SHI/STY gene activities via their GCC box. Independent studies on this protein performed by different research groups have resulted in several names; consequently, ESR2/DRNL/BOL is also known as SUPPRESSOR OF PHYB-2 (SOB2; Ward et al., 2006). ESR2/DRNL/BOL/SOB2 will hereafter be referred to only as DRNL.

Previous studies have demonstrated that DRNL has functions in flower organ initiation and outgrowth, particularly as an enhancer of the pistillata mutant with roles in stamen development (Nag et al., 2007). DRNL and its closest homolog, DRN, have been shown to act upstream of auxin transport and responses during embryo development and to have redundant roles during embryonic patterning and cotyledon organogenesis, likely in the same pathway as CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (Chandler et al., 2007, 2011a, 2011b).

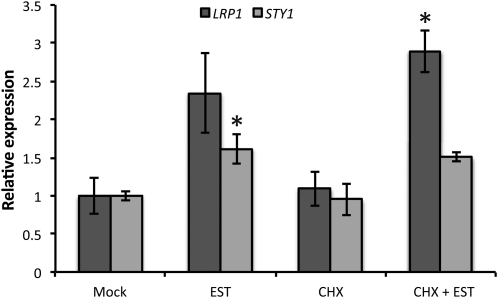

To verify that DRNL can activate SHI/STY genes, we analyzed the ability of DRNL to activate the transcription of STY1 and LRP1 in 35Spro:DRNL-ER seedlings after β-estradiol (EST)-mediated nuclear import of the constitutively expressed DRNL-ER fusion protein (Ikeda et al., 2006). CHX was added to inhibit translation and thus to eliminate secondary effects. DRNL-ER activation resulted in a significant up-regulation of transcript levels of STY1 and LRP1 detected by quantitative (q)RT-PCR (Fig. 4), further suggesting that DRNL can activate several SHI/STY genes. We also analyzed the ability of DRNL-ER to activate the STY1pro:GUS construct. An increased GUS signal intensity in EST-induced 35Spro:DRNL-ER STY1pro:GUS seedlings compared with mock-treated seedlings (Fig. 5, A and C) confirmed the DRNL-ER-dependent activation of the STY1 promoter.

Figure 4.

DRNL can activate SHI/STY genes. Transcript levels of SHI/STY family members STY1 and LRP1 in mock-, EST-, CHX-, and EST + CHX-treated 8- or 10-d-old 35Spro:DRNL-ER seedlings were measured using qRT-PCR. Graphs show mean values of three biological replicates (three technical replicates per biological sample). Error bars represent se of three biological replicates. The asterisks for STY1 and LRP1 denote significant (Student’s t test, P < 0.05) up-regulation compared with mock and CHX treatments, respectively.

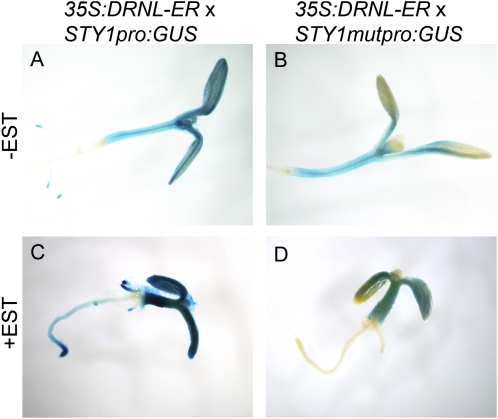

Figure 5.

DRNL requires a functional GCC box to activate STY1 in planta. A and C, Mock-treated (A) and EST-treated (C) STY1pro:GUS 35Spro:DRNL-ER. B and D, Mock-treated (B) and EST-treated (D) STY1mutpro:GUS 35Spro:DRNL-ER. Activation of DRNL by EST treatment results in thickening of the root and hypocotyls as well as a delay in cotyledon opening (C and D).

DRNL-Mediated Activation of STY1 in Aerial Parts Is GCC Box Dependent

To test whether a functional GCC box is required for DRNL-mediated activation of SHI/STY genes in planta, we crossed the 35Spro:DRNL-ER line with the STY1mutpro:GUS line. We compared GUS expression in STY1pro:GUS 35Spro:DRNL-ER and STY1mutpro:GUS 35Spro:DRNL-ER seedlings after growth on mock or EST-supplemented medium (Fig. 5). As mentioned above, we observed an elevated constitutive GUS expression in aerial parts, including newly formed leaves of EST-treated STY1pro:GUS 35Spro:DRNL-ER seedlings (Fig. 5, A and C). EST-treated STY1mutpro:GUS 35Spro:DRNL-ER seedlings, in contrast, did not show elevated or ectopic GUS activity (Fig. 5, B and D), suggesting that the GCC box indeed is required for DRNL-mediated activation of the STY1 promoter.

The Phenotypic Effects of Constitutive DRNL Activity Are Suppressed in the SHI/STY Family Multiple Mutant Background

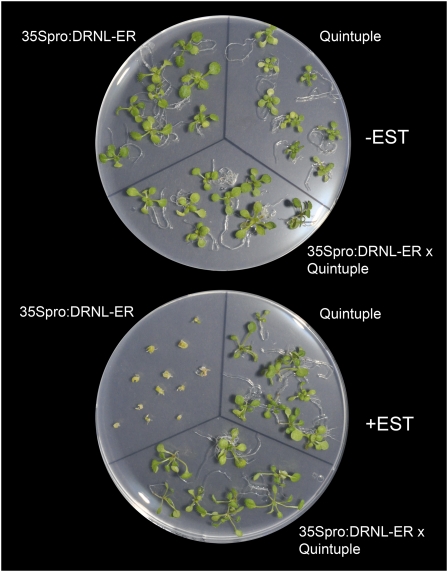

Ectopic expression of DRNL results in phenotypic alterations almost identical to those of 35Spro:SHI/STY1/STY2/LRP1 plants (Fridborg et al., 1999; Kuusk et al., 2002; Kirch et al., 2003; Ikeda et al., 2006; Marsch-Martinez et al., 2006; Nag et al., 2007). The most striking phenotypes are epinastic leaves, stunted misshaped siliques, short internodes and hypocotyls, and small pointed cotyledons, indicating that the cotyledon disc has not expanded properly. This suggests that the phenotypes caused by ectopic 35S promoter-driven DRNL expression might largely be mediated by DRNL-induced ectopic activity of SHI/STY family members. Therefore, we introduced the 35Spro:DRNL-ER construct into a SHI/STY multiple mutant background by crossing the 35Spro:DRNL-ER line with the SHI/STY quintuple mutant (sty1-1 sty2-1 shi-3 lrp1 srs5-1; Kuusk et al., 2006). Progeny of plants homozygous for 35Spro:DRNL-ER and with the severe SHI/STY family multiple mutant phenotype were EST or mock treated. Notably, EST treatment did not induce phenotypic changes in the SHI/STY family mutant seedlings to the same extent as in the wild-type background (Fig. 6), suggesting that the abnormalities induced by ectopic DRNL requires functional SHI/STY family members. These findings were supported by the inability of DRNL-ER to affect the development of seedlings in a 35Spro:STY1-SRDX background (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 6.

The phenotypes of seedlings constitutively expressing DRNL are mediated via SHI/STY genes. Plantlets of 35Spro:DRNL-ER, SHI/STY quintuple mutant (sty1-1 sty2-1 shi-3 lrp1 srs5-1), and 35Spro:DRNL-ER SHI/STY family multiple mutant lines, grown on mock treatment (top plate) or 10 μm EST (top plate) for 17 d, are shown.

Loss of DRN, DRNL, and PUCHI Functions Results in Reduced STY1 Expression

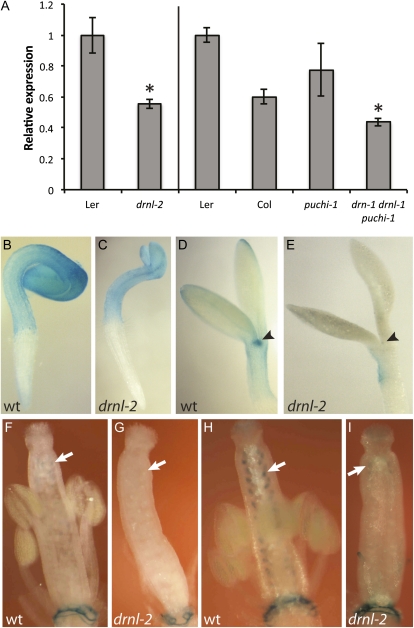

To test whether DRN and DRNL also regulate STY1 activity in their normal expression domains, we analyzed the STY1 transcript level in buds and seedlings of the drn-1 drnl-1 double mutant line but found no statistically significant reduction (data not shown). However, in seedlings carrying the stronger drnl-2 allele (Nag et al., 2007), the STY1 transcript level was significantly reduced compared with the wild-type level (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, STY1pro:GUS activity was reduced in cotyledons, shoot apices, and ovules of drnl-2 plants. In 1-d-old drnl-2 seedlings, GUS staining (2 h) was much reduced compared with wild-type seedlings (Fig. 7, B and C). Furthermore, we could not detect any GUS staining in 3-d-old drnl-2 seedlings after 1 h of incubation with the substrate (Fig. 7, D and E), whereas some staining was detected in the cotyledons after overnight incubation (data not shown). The GUS activity in ovules of stage 12 flowers incubated in GUS substrate for 6 h or overnight was dramatically reduced in drnl-2 plants compared with the wild type (Fig. 7, F–I). These tissues largely correspond to those losing STY1 promoter activity when the GCC box is mutated (Fig. 2), suggesting that DRNL activates STY1 transcription via the GCC box also in wild-type plants. In addition, when drnl-1 was combined with drn-1 as well as a mutation in PUCHI (Hirota et al., 2007), the closest homolog to the DRN/DRNL genes (Nakano et al., 2006), the STY1 mRNA level in seedlings was significantly reduced compared with both Col and Landsberg erecta (Ler; Fig. 7), further suggesting that not only DRNL, but also related proteins, play a role in the activation of STY1 transcription.

Figure 7.

Expression of STY1 is reduced in the drnl-2 and drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 mutant backgrounds. A, qRT-PCR-detected expression of STY1 was reduced at 10 d after germination in seedlings of drnl-2 and drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 mutant lines. Shown are averages of three biological replicates (three technical replicates per biological sample). Error bars represent se. The asterisk for drnl-2 denotes a significant reduction in STY1 expression compared with that of Ler (Student’s t test, P < 0.05); the asterisk for drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 denotes a significantly reduced expression level compared with both Ler and Col (Student’s t test, P < 0.05). Both ecotypes were used for comparison, as drn-1 and puchi-1 are in the Col background, whereas drnl-1 is in the Ler ecotype. B to I, STY1pro:GUS expression is reduced in drnl-2 seedlings and flowers. B and C, GUS staining (2 h of incubation) is reduced in cotyledons of 1-d-old drnl-2 seedlings compared with wild-type (wt) seedlings. D and E, No GUS staining was detected in cotyledons and the shoot apex (arrowheads) of 3-d-old drnl-2 seedlings after 2 h of incubation, whereas STYpro:GUS expression was strong at these sites in wild-type seedlings. F to I, STYpro:GUS activity was strongly reduced in drnl-2 ovules (arrows) compared with the wild type both after 6 h (F and G) and 24 h (H and I) of incubation.

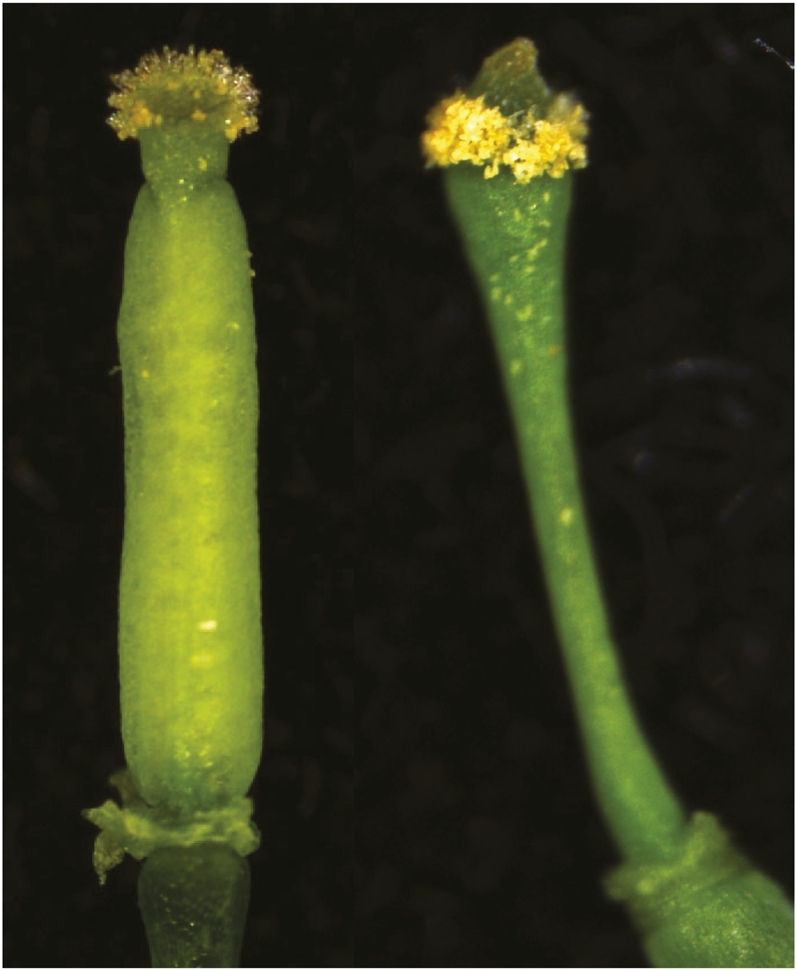

Mutations in DRNL, SHI/STY, and YUC Genes Results in Similar Phenotypic Defects during Gynoecium Development

The carpel valve length is significantly reduced in plants with a reduced level of SHI/STY gene activity, such as the SHI/STY quintuple mutant, and in plants expressing a STY1 protein transformed from a transcriptional activator to a repressor by the addition of a C-terminal SRDX tag (Kuusk et al., 2006; Eklund et al., 2010a). Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that around 25% of the drn-1 drnl-1 flowers have one or two shortened carpel valves and/or are missing one valve (Chandler et al., 2011b; Table II). Here, we can show that this gynoecium defect was more severe in drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutant plants, where 75% of the flowers had gynoecia with valve defects (Table II). In the triple mutant, some of the flowers also had valveless gynoecia with a protrusion of meristem-like tissue surrounded by a ring of stigma (Fig. 8), to our knowledge a new phenotype not seen in the drnl-2 single mutant, the drn-1 drnl-1 double mutant, or the puchi-1 single mutant. This indicates that DRN, DRNL, and PUCHI have redundant functions in gynoecium development. Furthermore, as similar gynoecium defects also are seen in the yuc1 yuc4 double mutant (Cheng et al., 2006), our data suggest a possible link between DRNL and related genes, STY1 and the STY1 downstream target YUC4, in gynoecium development.

Table II. The frequency of gynoecium defects is increased in drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutant flowers.

Values shown are percentages of flowers having different gynoecium defects. A total of 28 to 74 flowers were examined per genotype.

| Genotype | Shortened Valves | Missing One Valve | Missing Both Valves | No Defects |

| puchi-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| drn-1 drnl-1 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 85 |

| drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 | 13 | 35 | 27 | 25 |

Figure 8.

drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutants produce valveless gynoecia. At left is a wild-type (Col) gynoecium. At right is the valveless gynoecium of a drn drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutant, with a protrusion of meristem-like tissue surrounded by a ring of stigma. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

DISCUSSION

Although auxins act in many diverse developmental processes, surprisingly little is known about auxin biosynthetic enzymes, intermediates, and pathways, and even less is known about the transcription factors that regulate genes involved in auxin biosynthesis (for review, see Chandler, 2009). Here, we have focused on the regulation of SHI/STY members to establish further their role in IAA-mediated plant development.

A GCC Box in Upstream Regulatory Regions of SHI/STY Members Is Essential for Expression in Most Aerial Organs

When searching for conserved upstream regulatory elements in SHI/STY family members, we found putative GCC boxes in all genes except for SRS3. However, the protein or proteins recognizing the element in the STY1 promoter could still potentially recognize a rearranged element in SRS3 not found in our analysis. Consequently, it remains to be analyzed whether the apparent lack of a GCC box in SRS3 has resulted in major differences in its expression pattern compared with that of other SHI/STY genes. Although we have RT-PCR data suggesting that there are no major spatial differences in expression pattern among SHI/STY members in Arabidopsis, except that SRS3 is not expressed in leaves, we lack the resolution of a SRS3pro:GUS line or in situ hybridization data.

As shown previously, SHI/STY family members form two clades supported by high bootstrap values (Kuusk et al., 2006; Eklund et al., 2010b). We identified two main types of conserved GCC box-containing elements in SHI/STY members of Arabidopsis. Interestingly, one type was restricted to members of the LRP1/SRS6 clade and the other type to members of the STY1/SHI clade. Apparent similarities between members of the two clades could mean that the GGCGGC part of the conserved element is important for shaping expression patterns of SHI/STY members of both clades. However, the split into two different regulatory elements could have contributed to subfunctionalization within the SHI/STY family, by subjecting SHI/STY family members to new regulatory mechanisms.

The GCC Box Is Essential for STY1-Mediated Auxin Biosynthesis

We have previously shown that STY1 induces the transcription of YUC4 and YUC8, which are directly involved in the biosynthesis of IAA precursors (Sohlberg et al., 2006; Eklund et al., 2010a). Expression of STY1mutpro:GUS resulted in the loss of GUS signal in the cotyledon tip and style/stigma, where the SHI/STY downstream target YUC4 is expressed (Cheng et al., 2006, 2007), while STY1mutpro:GUS expression remained in regions where auxin biosynthesis is not reported to occur: in stems, petiole margins, and the proximal part of the cotyledon. This suggests that the GCC box is essential for the regulation of STY1-mediated auxin biosynthesis in the shoot. STY1, however, does not appear to be strongly regulated by changes in auxin levels (Fig. 3).

STY1mutpro:GUS Transformants Provide an Explanation for the Misleading GUS Signal in the lrp1 Mutant

The lrp1 mutant line, first described by Smith and Fedoroff (1995), was created by insertional mutagenesis with a gene trap transposon carrying a promoterless GUS gene. The insertion of the transposon, a DNA fragment of approximately 4 kb, is immediately in front of the GCC box-like regulatory region close to the TSS of LRP1. Hence, any cis-regulatory element in the 5′ UTR of LRP1 is unlikely to contribute to the regulation of GUS expression. In this line, GUS signal was detected only in lateral root primordia, and the corresponding gene, LRP1, was suggested to be a lateral root primordium-specific gene (Smith and Fedoroff, 1995). However, Kuusk et al. (2006) showed that the putative null mutant lrp1 enhances the gynoecium phenotype of the sty1-1 mutant and also that LRP1 transcripts are found by PCR-based methods in floral buds. Our results, implicating the strong lateral root primordium expression of STY1 to be GCC box-independent, explain the spatially limited GUS expression of the lrp1 mutant by suggesting that the GCC box in the 5′ UTR of LRP1 does not contribute to activating GUS expression in lrp1.

Ectopic Expression of DRNL Requires the GCC Box for the Activation of SHI/STY Genes

Our data clearly suggest that induction of the AP2/ERF protein DRNL activates the STY1 and LRP1 genes and that the expression of SHI/STY family members can explain some of the phenotypic effects of constitutive DRNL activity. First, we could show that the induction of constitutive DRNL expression results in activation of the STY1 and LRP1 promoters and that, at least for STY1, this activation required only a 1.3-kb upstream regulatory sequence present in the STY1pro:GUS construct. These data suggest that DRNL may participate in the transcriptional complex regulating SHI/STY gene activity. Second, we could also show that the growth defects induced by ectopic DRNL expression are dependent on the activity of SHI/STY family members, as organs developed more normally in lines constitutively expressing DRNL in a background carrying multiple knockdowns of SHI/STY genes or the dominant negative repressor construct 35Spro:STY1-SRDX. Our data also reveal that the DRNL-mediated activation of ectopic STY1pro:GUS activity in cotyledons is dependent on the GCC box, as DRNL failed to induce ectopic activity of the STY1mutpro:GUS line. Our conclusion is that ectopic DRNL activates ectopic SHI/STY expression and that the GCC box is required for this activation.

DRNL and DRN Act Redundantly with Other AP2/ERF Proteins in the Regulation of SHI/STY Activity

Because DRN/DRNL and SHI/STY family members have overlapping expression patterns in the globular embryo, in the tips of cotyledon primordia in the embryo, in the leaf primordia and the distal tip of young leaves, in hydathodes, and in the stipules, ovules, and carpels (Fridborg et al., 2001; Kuusk et al., 2002, 2006; Kirch et al., 2003; Ikeda et al., 2006; Nag et al., 2007; Supplemental Fig. S2), and because DRNL clearly can induce SHI/STY gene activity, it appeared possible that DRNL could be involved in regulating the spatial and temporal activity of SHI/STY genes during plant development. However, the lack of DRNL activity in the style and receptacle suggests that other proteins may also activate STY1. DRN and DRNL have been suggested to have a highly redundant function in embryonic patterning and cotyledon formation in the same pathway as MONOPTEROS (Chandler et al., 2007, 2011a; Cole et al., 2009), suggesting that DRN could act as an upstream regulator of SHI/STY promoters as well. Although we were unable to detect alterations in STY1 mRNA levels or STYpro:GUS/SHIpro:GUS expression in the drn-1 drnl-1 double mutant (data not shown), a significant reduction of STY1 mRNA levels was found in seedlings of the stronger drnl-2 mutant allele (Nag et al., 2007) as well as of the drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutant (Fig. 7). Furthermore, STY1pro:GUS activity was reduced in drnl-2 seedlings and gynoecia. Hence, DRNL does activate SHI/STY during plant development, but additional factors such as DRN and PUCHI appear to act redundantly with DRNL. This hypothesis is strongly supported by the enhancement of the drnl-1 cotyledon defect in the drn drnl mutant (Chandler et al., 2011a) and of the drn-1 drnl-1 valve defects in the drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1 triple mutant (this study) as well as the carpel valve phenotype in the single drnl-2 mutant (Chandler et al., 2011b). Because the valve lengths also are affected in SHI/STY multiple mutants, it is likely that DRN, DRNL, and PUCHI mediate their control of valve development via the SHI/STY genes. Interestingly, constitutive expression of LEP, another AP2/ERF gene belonging to subgroup VIII, results in phenotypes resembling those of constitutive DRNL or STY1 activity (Ward et al., 2006), suggesting that there could be additional upstream regulators of SHI/STY1 among the AP2/ERF proteins. In addition, as DRNL is not expressed in the style, STY expression in this tissue is most likely mediated by another protein acting via the GCC box, potentially some of the other subgroup VIII proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioinformatic Analysis

Conserved motifs in upstream regulatory regions were investigated by MEME 4.0.0 (Bailey and Elkan, 1994; http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html). Genome-wide searches for motifs in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) were performed using Patmatch version 1.1 (http://www.arabidopsis.org/cgi-bin/patmatch/nph-patmatch.pl).

Generation of Transgenic Lines

Plasmid pSRSGUS#7 (Kuusk et al., 2002) was mutated (GGCGGC to AAAAAA) with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using primers STY1sdmF and STY1sdmR (Supplemental Table S2). The resulting plasmid, pSTY1mutpro:GUS, was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, containing the helper plasmid pMP90, and introduced into Arabidopsis Col by A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Selected T3 lines were crossed to 35Spro:DRNL-ER (Ikeda et al., 2006).

An SRS4 promoter fragment was PCR amplified using primers SRS4P1SalI and SRS4P11BamHI (Supplemental Table S2). The fragment was cloned using the pCR-blunt II-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen), creating plasmid pSRS4.3. The promoter fragment was released by SalI/BamHI digestion and subsequently inserted into the two-component vector Bin-LhG4 (Craft et al., 2005), to create an SRS4pro:LhG4 transcriptional fusion. Transformation of A. tumefaciens and Arabidopsis was performed as described above. Selected T3 lines were crossed with a transgenic line carrying the pOp:GUS construct, allowing the SRS4 promoter to drive the expression of GUS. F1 SRS4pro>>GUS plants were analyzed for GUS expression.

A SHI/STY quintuple mutant (sty1-1 sty2-1 shi-3 lrp1 srs5-1; Kuusk et al., 2006) and a 35Spro:STY1-SRDX line (Eklund et al., 2010a) were crossed with 35Spro:DRNL-ER (Ikeda et al., 2006). The crosses resulted eventually in an F7 line homozygous for 35Spro:DRNL-ER with a distinct multiple SHI/STY mutant phenotype and an F3 line homozygous for 35Spro:DRNL-ER and 35Spro:STY1-SRDX.

ACC Treatment

Four-day-old etiolated STY1pro:GUS seedlings were mock treated or treated with 10 μm ACC for 24 h.

Gene Expression Analysis

qRT-PCR was performed as described previously (Sohlberg et al., 2006) using primers targeting ACTIN7 (ACT7) for normalization. Eight- to 10-d-old 35Spro:DRNL-ER seedlings, grown on liquid medium, were mock treated or treated with EST (10 μm; Sigma E8875) or CHX (10 μm) at 45 or 75 min or 2 h. Seven-day-old light-grown or etiolated Col seedlings were mock treated or treated with 5 μm IAA for 10, 20, and 30 min or 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h. drnl-2, puchi-1, drn-1 drnl-1 puchi-1, Ler, and Col seedlings were grown for 10 d. Primers targeting ACT7 are described by Sohlberg et al. (2006). Primers targeting STY1, LRP1, and GH3.3 are found in Supplemental Table S2.

Histochemical staining for GUS activity was performed using 5-bromo-4-chloroindolyl β-d-glucuronide as a chromogenic substrate according to Jefferson (1987). Plant tissues were incubated in GUS staining solution for 1, 2, 6, or 24 h and were destained in 70% ethanol. Samples were viewed in 50% ethanol and 50% glycerol and photographed using a stereo dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ1500) with a Nikon DS-Fi1 camera and NIS-Elements D2.30 imaging software.

The DRNpro:GUS line in this study was made by Kirch et al. (2003). The DRNLpro:GUS line was made by Ikeda et al. (2006). Genotyping of the drn-1 and drnl-1 mutant alleles is described by Chandler et al. (2007), and the drnl-2 mutant allele is described by Nag et al. (2007). The PUCHI mutant allele used was puchi-1 (Hirota et al., 2007). puchi-1 was genotyped using primers PUCHI_mark_F and PUCHI_mark_R (Supplemental Table S2).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Suppression of SHI/STY function by SRDX-induced conversion of STY1 from a transcriptional activator to a transcriptional repressor prevents the induction of developmental changes induced by ectopic DRNL expression.

Supplemental Figure S2. Expression of DRN, DRNL, and STY1 overlaps.

Supplemental Table S1. Localization of the additional six LRP1/SRS6-like GCC box elements.

Supplemental Table S2. PCR primers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yoshihisa Ikeda for kindly sharing the 35Spro:DRNL-ER line and Olof Emanuelsson for assistance with bioinformatics.

References

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. (1994) Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. AAAI Press, Menlo Park, CA, pp 28–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno H, Mase Y, Maekawa K. (2006) Analysis of functional domains and binding sequences of Arabidopsis transcription factor ESR1. Plant Biotechnol 23: 303–308 [Google Scholar]

- Barcala M, García A, Cabrera J, Casson S, Lindsey K, Favery B, García-Casado G, Solano R, Fenoll C, Escobar C. (2010) Early transcriptomic events in microdissected Arabidopsis nematode-induced giant cells. Plant J 61: 698–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JW. (2009) Local auxin production: a small contribution to a big field. Bioessays 31: 60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JW, Cole M, Flier A, Grewe B, Werr W. (2007) The AP2 transcription factors DORNROSCHEN and DORNROSCHEN-LIKE redundantly control Arabidopsis embryo patterning via interaction with PHAVOLUTA. Development 134: 1653–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JW, Cole M, Jacobs B, Comelli P, Werr W. (2011a) Genetic integration of DORNRÖSCHEN and DORNRÖSCHEN-LIKE reveals hierarchical interactions in auxin signalling and patterning of the Arabidopsis apical embryo. Plant Mol Biol 75: 223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JW, Jacobs B, Cole M, Comelli P, Werr W. (2011b) DORNRÖSCHEN-LIKE expression marks Arabidopsis floral organ founder cells and precedes auxin response maxima. Plant Mol Biol 76: 171–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. (2006) Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 20: 1790–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. (2007) Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2430–2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M, Chandler J, Weijers D, Jacobs B, Comelli P, Werr W. (2009) DORNROSCHEN is a direct target of the auxin response factor MONOPTEROS in the Arabidopsis embryo. Development 136: 1643–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft J, Samalova M, Baroux C, Townley H, Martinez A, Jepson I, Tsiantis M, Moore I. (2005) New pOp/LhG4 vectors for stringent glucocorticoid-dependent transgene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J 41: 899–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund DM, Ståldal V, Valsecchi I, Cierlik I, Eriksson C, Hiratsu K, Ohme-Takagi M, Sundström JF, Thelander M, Ezcurra I, et al. (2010a) The Arabidopsis thaliana STYLISH1 protein acts as a transcriptional activator regulating auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 22: 349–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund DM, Thelander M, Landberg K, Ståldal V, Nilsson A, Johansson M, Valsecchi I, Pederson ER, Kowalczyk M, Ljung K, et al. (2010b) Homologues of the Arabidopsis thaliana SHI/STY/LRP1 genes control auxin biosynthesis and affect growth and development in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Development 137: 1275–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feraru E, Friml J. (2008) PIN polar targeting. Plant Physiol 147: 1553–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridborg I, Kuusk S, Moritz T, Sundberg E. (1999) The Arabidopsis dwarf mutant shi exhibits reduced gibberellin responses conferred by overexpression of a new putative zinc finger protein. Plant Cell 11: 1019–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridborg I, Kuusk S, Robertson M, Sundberg E. (2001) The Arabidopsis protein SHI represses gibberellin responses in Arabidopsis and barley. Plant Physiol 127: 937–948 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. (2000) Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell 12: 393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieneisen VA, Xu J, Marée AF, Hogeweg P, Scheres B. (2007) Auxin transport is sufficient to generate a maximum and gradient guiding root growth. Nature 449: 1008–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen G, Guilfoyle T. (2002) Auxin-responsive gene expression: genes, promoters and regulatory factors. Plant Mol Biol 49: 373–385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao D, Ohme-Takagi M, Sarai A. (1998) Unique mode of GCC box recognition by the DNA-binding domain of ethylene-responsive element-binding factor (ERF domain) in plant. J Biol Chem 273: 26857–26861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota A, Kato T, Fukaki H, Aida M, Tasaka M. (2007) The auxin-regulated AP2/EREBP gene PUCHI is required for morphogenesis in the early lateral root primordium of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2156–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JK, Kim JS, Kim JA, Lee SI, Lim M-H, Park B-S, Lee Y-H. (2010) Identification and characterization of SHI family genes from Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis. Genes Genomics 32: 309–317 [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P. (2008) Genevestigator v3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinforma 2008: 420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, Banno H, Niu QW, Howell SH, Chua NH. (2006) The ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 gene in Arabidopsis regulates CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 at the transcriptional level and controls cotyledon development. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1443–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA. (1987) Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol Biol Rep 5: 387–405 [Google Scholar]

- Kirch T, Simon R, Grünewald M, Werr W. (2003) The DORNROSCHEN/ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 gene of Arabidopsis acts in the control of meristem cell fate and lateral organ development. Plant Cell 15: 694–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky A, Zaltsman A, Kozlovsky SV, Tian GW, Citovsky V. (2009) Regulation of root elongation by histone acetylation in Arabidopsis. J Mol Biol 385: 45–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusk S, Sohlberg JJ, Long JA, Fridborg I, Sundberg E. (2002) STY1 and STY2 promote the formation of apical tissues during Arabidopsis gynoecium development. Development 129: 4707–4717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusk S, Sohlberg JJ, Magnus Eklund D, Sundberg E. (2006) Functionally redundant SHI family genes regulate Arabidopsis gynoecium development in a dose-dependent manner. Plant J 47: 99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljung K, Hull AK, Celenza J, Yamada M, Estelle M, Normanly J, Sandberg G. (2005) Sites and regulation of auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 17: 1090–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch-Martinez N, Greco R, Becker JD, Dixit S, Bergervoet JH, Karaba A, de Folter S, Pereira A. (2006) BOLITA, an Arabidopsis AP2/ERF-like transcription factor that affects cell expansion and proliferation/differentiation pathways. Plant Mol Biol 62: 825–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo N, Banno H. (2008) The Arabidopsis transcription factor ESR1 induces in vitro shoot regeneration through transcriptional activation. Plant Physiol Biochem 46: 1045–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag A, Yang Y, Jack T. (2007) DORNROSCHEN-LIKE, an AP2 gene, is necessary for stamen emergence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 65: 219–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Suzuki K, Fujimura T, Shinshi H. (2006) Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol 140: 411–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonhebel H, Yuan Y, Al-Amier H, Pieck M, Akor E, Ahamed A, Cohen JD, Celenza JL, Normanly J. (2011) Redirection of tryptophan metabolism in tobacco by ectopic expression of an Arabidopsis indolic glucosinolate biosynthetic gene. Phytochemistry 72: 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. (1990) Structure and expression of a tobacco beta-1,3-glucanase gene. Plant Mol Biol 15: 941–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Skirpan AL, Liu X, Christensen A, Slewinski TL, Hudson C, Barazesh S, Cohen JD, Malcomber S, McSteen P. (2011) vanishing tassel2 encodes a grass-specific tryptophan aminotransferase required for vegetative and reproductive development in maize. Plant Cell 23: 550–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinshi H, Usami S, Ohme-Takagi M. (1995) Identification of an ethylene-responsive region in the promoter of a tobacco class I chitinase gene. Plant Mol Biol 27: 923–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Fedoroff NV. (1995) LRP1, a gene expressed in lateral and adventitious root primordia of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 7: 735–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohlberg JJ, Myrenås M, Kuusk S, Lagercrantz U, Kowalczyk M, Sandberg G, Sundberg E. (2006) STY1 regulates auxin homeostasis and affects apical-basal patterning of the Arabidopsis gynoecium. Plant J 47: 112–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ståldal V, Sohlberg JJ, Eklund DM, Ljung K, Sundberg E. (2008) Auxin can act independently of CRC, LUG, SEU, SPT and STY1 in style development but not apical-basal patterning of the Arabidopsis gynoecium. New Phytol 180: 798–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova AN, Robertson-Hoyt J, Yun J, Benavente LM, Xie DY, Dolezal K, Schlereth A, Jürgens G, Alonso JM. (2008) TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell 133: 177–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader LC, Bartel B. (2008) A new path to auxin. Nat Chem Biol 4: 337–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Ferrer JL, Ljung K, Pojer F, Hong F, Long JA, Li L, Moreno JE, Bowman ME, Ivans LJ, et al. (2008) Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell 133: 164–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivendale ND, Davies NW, Molesworth PP, Davidson SE, Smith JA, Lowe EK, Reid JB, Ross JJ. (2010) Reassessing the role of N-hydroxytryptamine in auxin biosynthesis. 154: 1957–1965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Smith AM, Shah PK, Galanti SE, Yi H, Demianski AJ, van der Graaff E, Keller B, Neff MM. (2006) A new role for the Arabidopsis AP2 transcription factor, LEAFY PETIOLE, in gibberellin-induced germination is revealed by the misexpression of a homologous gene, SOB2/DRN-LIKE. Plant Cell 18: 29–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. (2010) Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 49–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Cashman JR, Cohen JD, Weigel D, Chory J. (2001) A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science 291: 306–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Hull AK, Gupta NR, Goss KA, Alonso J, Ecker JR, Normanly J, Chory J, Celenza JL. (2002) Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev 16: 3100–3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]