Abstract

Previous research has revealed a negative impact of orphanhood and HIV-related stigma on the psychological well-being of children affected by HIV/AIDS. Little is known about psychological protective factors that can mitigate the effect of orphanhood and HIV-related stigma on psychological well-being. This research examines the relationships among several risk and protective factors for depression symptoms using structural equation modeling. Cross-sectional data were collected from 755 AIDS orphans and 466 children of HIV-positive parents aged 6–18 years in 2006–2007 in rural central China. Participants reported their experiences of traumatic events, perceived HIV-related stigma, perceived social support, future orientation, trusting relationships with current caregivers, and depression symptoms. We found that the experience of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma had a direct contributory effect on depression among children affected by HIV/AIDS. Trusting relationships together with future orientation and perceived social support mediated the effects of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma on depression. The final model demonstrated a dynamic interplay among future orientation, perceived social support and trusting relationships. Trusting relationships was the most proximate protective factor for depression. Perceived social support and future orientation were positively related to trusting relationships. We conclude that perceived social support, trusting relationships, and future orientation offer multiple levels of protection that can mitigate the effect of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma on depression. Trusting relationships with caregivers provides the most immediate source of psychological support. Future prevention interventions seeking to improve psychological well-being among children affected by HIV/AIDS should attend to these factors.

Keywords: China, AIDS orphans, experience of traumatic events, perceived HIV-related stigma, perceived social support, future orientation, trusting relationships, depression

Introduction

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has contributed to a dramatic increase in orphans worldwide. In 2005, more than 15 million children under the age of 18 years had lost one or both parents to AIDS worldwide (UNICEF, 2007). Sub-Saharan Africa is the most severely affected region, accounting for more than 80% of children orphaned by AIDS (UNAIDS, 2010). The number of children orphaned by AIDS worldwide could reach 40 million by 2020 (UNICEF, 2009). A substantial body of research has explored the impact of orphanhood on the well-being of children in the past few years. These studies found that children whose parents were infected with or died of HIV/AIDS suffered from psychological problems including depression, anxiety, anger, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (Atwine et al., 2005; Cluver et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009). Despite the abundance of descriptive literature, little is known about psychological protective factors that can mitigate the effect of traumatic life events and HIV-related stigma on mental health.

Traumatic life events and HIV-related stigma-a double burden for AIDS orphan

Previous research has found that traumatic life events are associated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression (Cluver et al., 2011; Krupnick et al., 2004; Suliman et al., 2009). Losing one or both parents during childhood is one of the most traumatic events for a child (Haine et al., 2008). Attachment theory posits that children have a need for a secure relationship with an adult caregiver for normal social and emotional development (Bowlby, 1982). The loss of one or both parents generally exposes the child to increased stress and results in increased psychological symptoms that can be detrimental to the child’s well-being (Thompson et al., 1998). A cross-sectional study in China found that children affected by HIV/AIDS compared to those who have not been directly impacted by HIV/AIDS reported higher exposure of traumatic life events and more psychosocial adjustment problems, including depression and impaired self-esteem (Li et al., 2009).

In addition to anxiety experienced during the years of parental illness and grief and trauma following the death of a parent, children affected by HIV/AIDS are subject to stigma associated with the disease (Pivnik &Villegas, 2000). HIV-related stigma represents a double burden for these children (Messer et al., 2010). High levels of HIV-related stigma and discrimination has been reported among affected communities in South Africa, ranging from rejection to physical assault (Skinner & Mfecane, 2004). Research conducted in African countries has found that HIV/AIDS affected children suffer from stigma and discrimination at home, school and in their leisure environments (Ostrom et al., 2006). In a study of stigma towards AIDS-orphaned adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa, AIDS-orphaned adolescents reported higher levels of stigma than adolescents orphaned by non-AIDS causes and non-orphaned adolescents; Stigma was associated with poorer psychological outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress) (Cluver et al., 2008). In a study among patients in care for HIV in the US, all of the families interviewed recounted experiences with stigma and 79% of families experienced actual discrimination (Bogart et al., 2008). Preliminary data from rural China indicates the existence of stigma towards children in HIV/AIDS affected families, including isolation, ignorance and rejection (Xu et al., 2009). Furthermore, previous research found that the experience of stigma can reduce levels of social support and increase a sense of isolation for already vulnerable groups (Cluver et al., 2008).

Psychological protective factors for depression of children affected by HIV/AIDS: future orientation, trusting relationship, and perceived social support

“Future orientation refers to an individual’s thoughts, plans, motivations, and feelings about his or her future” (McCabe & Barrnett, 2000; p. 491). Future orientation is a multidimensional concept that includes such dimensions as future expectation, hope and perceived control. Previous research has found that future orientation has a protective effect on children’s mental health (McCabe & Barrnett, 2000; Snyder et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2009). Snyder and Lopez (2005) found that positive expectations yield higher confidence and people who have positive expectations about the future more easily confront adversity or difficulty. Snyder (2001) found that hope seems to mediate the relationship between unforeseen stressors and successful coping and is positively related with an individual’s psychological health. Another cognitive factor related to future expectation and hope is perceived control over the future, which has also been found to be positively associated with an individual’s mental health (Haine et al. 2003).

The broader mental health literature provides evidence for a positive effect of social support on children’s psychological wellbeing. Lack of social support and lower perceived adequacy of social support have been linked to poor mental health (Allgöwer et al., 2001; Decker 2007). Social support functions as a “buffer” to reduce distress and enhance coping for people in stressful life events (Callaghan & Morrissey, 1993; Hong et al., 2010). A higher perceived availability of social support was found to be directly associated with fewer symptoms related to trauma among a group of adolescents who suffered a stressful event (Bal et al., 2003). However, limited data are available regarding social support and psychological health among children affected by AIDS. In a two-year intervention study among adolescents whose parents were infected with HIV/AIDS, it was found that reductions in depression, conduct problems, and problem behaviors were significantly associated with better social support (Lee et al., 2007). A qualitative study conducted in Southwest China reported that children living in HIV/AIDS affected families were suffering from a number of psychological problems including fear, anxiety, grief, and loss of self-esteem and confidence and the children relied heavily on caregivers and peers to gain psychological support (Xu et al., 2009).

The quality of a child’s attachment relationships with current caregivers after the loss or risk of loss of one or both of their parents has been identified as important for a child’s socio-emotional functioning and general well-being (Fraley & Shaver, 1999; Waters et al., 2000). A study of psychosocial adjustment among AIDS-orphaned adolescents found that greater caregiver-child connection was associated with less anxiety and depression (Wild et al., 2006). Lower caregiver-child connectedness was found to be associated with a higher level of depression, especially among male orphans (Kaggwa & Hindin, 2010). These studies have identified the relationship between orphans and their primary caregiver as an important protective factor for orphans’ psychological well-being. However, previous research has investigated these protective and risk factors for mental health individually or in pairs, as opposed to examining several variables together.

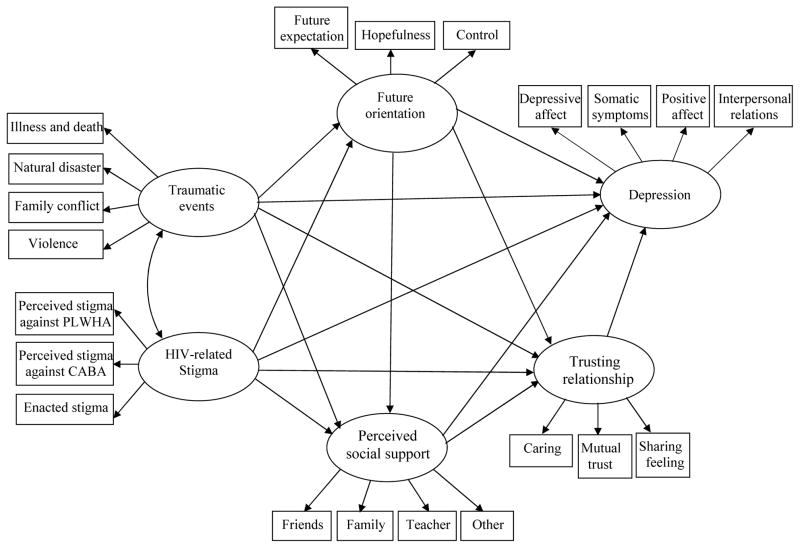

Based on the results of prior research, we constructed a hypothesized conceptual model (Figure 1). In this model, we hypothesize that future orientation, trusting relationships, and perceived social support mediate the effect of traumatic life events and HIV-related stigma on depression. The three mediating variables represent individual, family and community level factors that may positively affect children’s mental health. In addition, traumatic life events and HIV-related stigma were hypothesized to have a direct effect on depression.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of traumatic events, HIV-related stigma, trusting relationship, future orientation, perceived social support, and mental health relationships.

AIDS orphans in China

Although most children orphaned by AIDS reside in Africa, the China Ministry of Health has estimated that there are at least 100,000 AIDS orphans in China, the majority of whom reside in rural, central China (Hong et al., 2011). The HIV/AIDS epidemic in central China was caused by the practice of unhygienic blood/plasma collection (China Ministry of Health, 2003), which is different from the corresponding epidemic in the African context, where the predominant mode of transmission is heterosexual intercourse. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, some governmental and commercial blood centers collected blood from poor farmers in central China. Without testing the farmer’s blood for HIV and other blood-borne infections, the blood collection centers pooled the blood of several donors of the same blood type to separate the plasma, and infused the remaining red blood cells back into individual donors to prevent anemia. This practice, along with the reusing of needles and contaminated equipment, enabled a rapid spread of HIV virus among the local population. Consequently, a large number of these farmers succumbed to AIDS, leaving behind thousands of orphans.

The existing research has underscored the importance of intervention efforts to improve mental health among children affected by HIV/AIDS. With an ultimate goal to inform the development of effective psychosocial intervention among these children, the current study was designed to achieve the following specific aims: (1) to examine associations of traumatic life events and HIV-related stigma with psychological protective factors (i.e., future orientation, trusting relationship, and perceived social support), (2) to examine associations between psychological protective factors and depression, and (3) to examine the extent to which psychological protective factors mediate associations between traumatic life events, HIV-related stigma and depression.

METHODS

Study site and participants

The data in this study were collected in 2006–2007 in two rural counties in central China where many residents (mostly farmers) had been infected with HIV through unhygienic blood collection practices. These counties are believed to have the highest prevalence of HIV infection in the area. Although official prevalence data were not available for these counties, local epidemiological surveys reported HIV infection rates were as high as 9.1% to 15.3% in some of the villages in these counties (Cheng et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2006), compared to a national rate of 0.1% among adults (UNAIDS, 2010). The two counties had similar demographic and economic profiles. We obtained village-level HIV surveillance data from the anti-epidemic station of each county to identify the villages with the highest number of deaths due to HIV/AIDS or individuals with confirmed HIV infection.

The participants in the current study were recruited from five administrative villages within a county that had jurisdiction over 111 villages. The participants in the current study include 755 AIDS orphans (defined as children who lost one or both of their parents to HIV/AIDS) (Nyambedha et al., 2003) and 466 children of HIV-positive parents. Children 6–18 years of age were eligible to participate in the study. Age eligibility was verified through the local community leaders, school records, or caregivers. Children with HIV infection were eligible to participate, although the number of such children was estimated to be very small and no HIV testing was conducted in the current study.

Sampling Procedure

The recruitment process for the current study has been described in detail elsewhere (Li et al., 2009). Briefly, the orphan sample (n=755) was recruited from four government-funded orphanages (n=176), eight community-based small group homes (n=30), and family and kinship care settings (n=549). Approximately 72% of AIDS orphans in the four AIDS orphanages and 70% of AIDS orphans living in eight group homes participated in the survey. The children of HIV-positive parents (n=466) were recruited from the family or kinship care settings. We worked with village leaders to generate lists of families caring for orphans and of families with a confirmed diagnosis of parental HIV/AIDS. Because of the implementation of the Chinese government’s AIDS relief programs in our study areas (e.g., free schooling for AIDS orphans and children affected by HIV/AIDS), most of the school-age children (93%) were attending school (Li et al., 2009). Therefore, most data collection took place at local schools. We approached children and their caregivers in 40 schools in our sampling areas until the target sample size of 1,200 AIDS orphans and children of HIV-positive parents was achieved. The research protocol, including the consent process, was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both Wayne State University in the US and Beijing Normal University in China.

Survey Procedure

The interviewers were trained faculty and graduate students from education and psychology departments at local Chinese universities. The interviewers administered the assessment survey in Mandarin to children individually or in small groups. The survey included detailed measures of demographic information and several scales of psychosocial adjustment. For children with limited literacy, interviewers read each question to them, and the children gave oral responses to the interviewers who recorded the responses on the survey form. During the survey, necessary clarification or instruction was provided promptly when requested. The entire assessment procedure took about 75 to 90 minutes, depending on the age of the child. Children less than 8 years of age were offered a 10–15 minute break after every 30 minutes of assessment. Parents or caregivers were not allowed to stay with the participant during the assessment. Each child received a gift at completion of the assessment as a token of appreciation.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Children were asked to report on individual and family characteristics including age, sex, ethnicity, perceived health status (i.e., very good, good, fair, and poor), and number of siblings in the family.

Life incidence of traumatic events

A modified version of the Life Incidence of Traumatic Events-Student Form (LITE-S: Greenwald & Rubin, 1999) was employed to assess the children’s experiences of traumatic events. Four items were added to the original 17-item LITE-S to cover the potential traumatic events of HIV-related illness or death among parents or relatives. The modified checklist asked children to indicate whether each of the events ever happened to them (yes/no). The 21 items were assigned to four domains: traumatic events related to victim or witness of accident, injury, illness, or death (illness and death, 10 items), the traumatic events related to natural disaster, such as flood, and fire (natural disaster, 3 items); the traumatic events related to family conflict, such as parental divorce (family conflict, 3 items), and traumatic events related to violence (violence, 5 items). The Cronbach alphas for these four subscales were 0.60, 0.49, 0.54, and 0.71, respectively.

Future orientation

Three scales were employed to measure children’s future orientation: the Children’s Future Expectation Scale, the Hopefulness about the Future Scale, and the Perceived Control over the Future Scale.

Children were asked to complete a modified version of the Children’s Future Expectation Scale (Bryan et al., 2005). This modified version consists of six items assessing expectations about specific future outcomes in life (e.g., handling problems in life, handling school work, having friends, staying out of trouble, having a happy life, and having interesting things to do). Children were asked to indicate along a 5-point scale (1=not at all to 5=very much) how sure they were that these positive outcomes would actually occur in the future. The Cronbach alpha for the scale was 0.84.

The 4-item Hopefulness about the Future Scale (Whitaker et al., 2000) was employed to assess child’s hopefulness with regard to specific outcomes in the future (e.g., How likely you will graduate from high school some day?). The items in the scale (labeled “hopefulness”) have a 4-point response option (ranging from 1=will not happen to 4=will definitely happen). The Cronbach alpha for the scale was 0.74.

The seven-item Perceived Control over the Future Scale (Whitaker et al., 2000) was employed to assess child’s perceived control over the future (e.g., What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me). The children indicated degree of agreement with each of the statements with a four-point response option (ranging from 1=disagree a lot to 4=agree a lot). The Cronbach alpha for the scale (labeled “control”) was 0.64.

Trusting relationships

The child version of the Trusting Relationship Questionnaire (TRQ; Mustillo et al., 2005) was modified in the current study to assess the quality of relationship between the child and his or her current caregiver(s). Following the recommendations from the developers of the original TRQ (Mustillo et al., 2005), 14 of the original 16 items were retained in the current study. One new item was added to the scale to assess whether children took the initiative in seeking help from caregivers during the time of crisis (i.e., Do you initiate contact with [name of adult] when you in difficulties?). All items were presented on a 5-point scale (1= never to 5= always).

Responses to the 15 items were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis. The principal component method with oblique rotation was used to extract the factors. The scree test suggested three meaningful factors which were grouped together as the “caring” (four items), “mutual trust” (seven items), and “sharing feeling” (four items) subscales. The “caring” subscale measures the extent to which the caregiver cares for the child and communicates with him/her. The “mutual trust” subscale measures the extent to which the caregiver and the child consider each other’s point of view and spend time together. The “sharing feeling” subscale measures the extent to which the caregiver and the child share information/feeling with each other. The Cronbach alphas for these three subscales were 0.73, 0.84, and 0.69, respectively.

Perceived social support

Children’s perceived social support was measured using an existing social support scale that has been used and validated among children affected by HIV in rural China (Hong et al., 2010). The scale included 16 items assessing the perceived or actual support from various sources (i.e., family, friends, teachers, or significant others) using a 5-point response option (ranging from 1= Very strongly disagree to 5= Very strongly agree). The sample questions include: I can talk about my problems with my family, I have friends who can share my joys and sorrow, I can count on my teachers when things go wrong, and There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings. The Cronbach alphas for these four subscales (i.e., family, friends, teacher, or other) were 0.73, 0.71, 0.74, and 0.71, respectively.

HIV-related stigma

Three scales were employed to measure HIV-related stigma in the current study: the perceived stigma against PLWHA scale, the perceived stigma against children affected by AIDS (CABA) scale, and enacted stigma scale.

Perceived stigma against PLWHA

A 10-item scale was used to assess children’s perceptions of public stigma against PLWHA (Berger et al., 2001; Kalichman et al., 2005). Children were asked to indicate, in their opinion, how many people (most, some, few, and none) in the community/society would have certain stigmatizing attitudes or actions toward PLWHA and their family (e.g., People will think someone with HIV is unclean; People will look down at someone who has HIV, People will look down on a family if someone in the family has HIV). The Cronbach alpha for the scale was 0.86.

Perceived stigma against CABA

Children’s perceived public stigma against children affected by AIDS was measured using the SACAA scale (Zhao et al., 2010). The SACAA (Stigma Against Children Affected by AIDS) scale includes a total of 10 items with three items measuring social sanction or exclusion against children affected by HIV (e.g., People think children of PLWHA should leave their villages, People think children of PLWHA should quit school or never go to school), four items measuring purposeful avoidance (e.g., People are unwilling to take care of children of PLWHA, People do not want their children to play with children of PLWHA), and three items measuring perceptions that children affected by HIV are inferior to children of uninfected parents (e.g., People think children of PLWHA are unclean, People do not think children of PLWHA can be as good as other children). The Cronbach alpha for the SACAA scale was 0.88.

Enacted stigma

Children affected by HIV were asked to indicate, on a 14-item list, whether they had experienced some stigmatization acts or their consequences. The sample stigmatizing experience included: being beaten by other kids, being called bad names, being teased or picked on by other kids, kids did not play with me anymore, relatives stopped visiting when parents got sick or died, and my family lost land or other property. The response options ranged from “never happened” to “always happened”. The Cronbach alpha of the scale was 0.88.

Depression

Children’s depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC), which has been validated for use in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years (Fendrich et al., 1990; Li et al., 2010). The scale is a 20-item self-report depression measure with a four-point response option (0= not at all, 1= a little, 2= some, 3= a lot). Sample items include: I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me. The 20 items are divided into four domains including depressive affect (7 items), somatic symptom (7 items), positive affect (4 items), and interpersonal relations (2 items). The Cronbach alphas for these four subscales were 0.81, 0.67, 0.55, and 0.61, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive statistics were calculated for socio-demographic variables. The differences of socio-demographic variables between AIDS orphans and children of HIV-positive parents were tested using chi-square and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Statistics (for categorical variables) or analysis of variance (for continuous variables). Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations) were calculated for all indicator variables of six latent constructs. In addition, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the strength of associations between all indicator variables. Distributions of the variables in the measurement model were examined and found to be normally distributed. Second, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesized mediation model that specifies the relationship among traumatic events, HIV-related stigma, future orientation, trusting relationship, perceived social support, and depression. This analysis involved a two-step process. First, a measurement model was tested using confirmatory factor analysis to examine the relationships between the latent constructs and their indicator variables. Standardized factor loadings were calculated for each indicator variable.

Second, a structural model was constructed to test the hypothesized relationships between all latent constructs. These analyses were performed using the SAS System’s CALIS procedure with the maximum likelihood method of parameter estimation, and were performed on the covariance matrix. Standardized regression coefficients for all paths were estimated. Goodness of model fit was evaluated using the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), chi-square to degrees-of-freedom (df) ratio, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI) and non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) (Hatcher, 2005). Acceptable model fit is determined by an RMSEA less than 0.08, and values of GFI, CFI and NNFI greater than 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Hatcher, 2005). To explore whether the effect of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma on depression is significantly reduced upon the inclusion of the mediators (future orientation, trusting relationship, and perceived social support) into the model, we tested the mediation effect using the Sobel test, a commonly used method for testing the significance of the mediation effect (Sobel, 1982). Missing data accounted for no more than 2% of any variables in this study and were imputed using mean replacement method. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of study sample

As shown in Table 1, our study sample consisted of 622 boys and 599 girls. The mean age was 12.86 years and did not significantly differ between boys and girls. AIDS orphans were older than children of HIV-positive parents (13.16 vs. 12.36 years; p<.0001). Over 98% of the children were of Han ethnicity, the predominant ethnic group in China. There was no significant difference in the number of siblings between orphans and children of HIV-positive parents (1.58 vs. 1.67, p>0.05). The proportion of children who perceived their health status to be “very good” or “good” was similar between AIDS orphans (63%) and children of HIV-positive parents (65%). Gender differences were found in some of the indicator variables.

Table 1.

Individual Characteristics of Study Sample

| Characteristics | Overall | AIDS Orphans | Children of HIV-positive parents | t or χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%)a | 1221 | 755 | 466 | |

| Boys | 50.9% | 53.4% | 47.0% | 4.69* |

| Girls | 49.1% | 46.6% | 53.0% | |

| Han ethnicity (%) | 98.4% | 98.8% | 97.7% | 1.99 |

| Age (yrs) Mean (SD)† | 12.86(2.25) | 13.16 (2.20) | 12.36(2.24) | 6.12*** |

| <10 | 8.8% | 6.4% | 12.7% | 42.91*** |

| 10- | 34.7% | 30.1% | 42.3% | |

| 13- | 43.2% | 48.6% | 34.5% | |

| 16–18 | 13.3% | 15.0% | 10.5% | |

| Health status | ||||

| Very Good | 28.7% | 26.8% | 31.8% | 3.29 |

| Good | 34.9% | 35.9% | 33.4% | |

| Fair | 31.7% | 32.6% | 30.2% | |

| Poor | 4.7% | 4.7% | 4.6% | |

| Siblings Mean (SD)† | 1.61(1.42) | 1.58(1.46) | 1.67(1.36) | −1.01 |

Note:

student t test. SD=standard deviation.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Bivariate Correlations among Manifest Indicator Variables

The bivariate correlations for the manifest indicator variables are shown in Table 2. Most of the correlation coefficients are statistically significant at the p<0.01 level. The indicator variables of same latent construct are strongly correlated with each other (p<0.001) except indicator variables of depression (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients of observed indicator variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traumatic events | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Illness and death | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Natural disaster | 0.28c | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Family conflict | 0.31c | 0.33c | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Violence | 0.28c | 0.47c | 0.47c | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| HIV-related stigma | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Stigma against-PLWHA | 0.09b | 0.11c | 0.11c | 0.15c | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Stigma-CABA | −0.06a | 0.11c | 0.10c | 0.17c | 0.40c | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Enacted stigma | 0.05 | 0.12c | 0.12c | 0.14c | 0.66c | 0.43c | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Future orientation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Future expectation | 0.05 | −0.06a | −0.06a | −0.10b | −0.20c | −0.33c | −0.19c | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 9. Hopefulness | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.06a | −0.12c | −0.15c | −0.30c | −0.16c | 0.48c | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 10. Control | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.09b | −0.20c | −0.09b | 0.41c | 0.49c | 1 | |||||||||||

| Perceived social support | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Family | 0.03 | −0.07a | −0.05 | −0.08b | −0.18c | −0.25c | −0.15c | 0.29c | 0.23c | 0.20c | 1 | ||||||||||

| 12. Friends | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.07a | −0.13c | −0.21c | −0.10c | 0.25c | 0.21c | 0.16c | 0.58c | 1 | |||||||||

| 13. Teacher | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.13c | −0.10c | −0.10c | 0.21c | 0.18c | 0.13c | 0.51c | 0.51c | 1 | ||||||||

| 14. Other | 0.07a | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.07a | −0.18c | −0.29c | −0.16c | 0.25c | 0.20c | 0.15c | 0.63c | 0.59c | 0.44c | 1 | |||||||

| Trusting relationship | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Caring | −0.12c | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.06a | −0.18c | −0.08b | 0.20c | 0.20c | 0.14c | 0.30c | 0.29c | 0.19c | 0.30c | 1 | ||||||

| 16. Mutual trust | −0.13c | −0.06a | 0.01 | −0.09b | −0.15c | −0.35c | −0.16c | 0.30c | 0.26c | 0.22c | 0.39c | 0.37c | 0.24c | 0.39c | 0.56c | 1 | |||||

| 17. Sharing feeling | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10c | −0.05 | 0.14c | 0.13c | 0.11c | 0.27c | 0.27c | 0.25c | 0.22c | 0.54c | 0.50c | 1 | ||||

| Depression | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Depressive affect | 0.25c | 0.13c | 0.22c | 0.19c | 0.22c | 0.03 | 0.21c | −0.08b | −0.05 | 0.07a | −0.07a | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.07a | −0.01 | −0.08b | 1 | |||

| 19. Somatic symptoms | 0.26c | 0.18c | 0.24c | 0.19c | 0.19c | −0.01 | 0.17c | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.14c | −0.01 | 0.06a | 0.03 | 0.07a | −0.09b | −0.07a | −0.13c | 0.73c | 1 | ||

| 20. Positive affect | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.10c | 0.11c | 0.04 | −0.14c | −0.13c | −0.06a | −0.20c | −0.17c | −0.17c | −0.17c | 0.13c | 0.18c | 0.12c | 0.01 | −0.14c | 1 | |

| 21. Interpersonal relations | 0.18c | 0.15c | 0.22c | 0.20c | 0.24c | 0.14c | 0.23c | −0.09b | −0.09b | −0.01 | −0.10c | −0.07a | −0.01 | −0.07a | 0.02 | −0.07a | −0.10c | 0.58c | 0.53c | −0.03 | 1 |

| Mean | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 27.2 | 36.3 | 28.3 | 19.9 | 11.2 | 16.8 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 11.6 | 11.5 | 13.0 | 20.3 | 11.5 | 5.29 | 5.76 | 7.04 | 1.26 |

| Standard deviation | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 4.3 | 4.33 | 3.56 | 2.67 | 1.50 |

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01;

p≤0.001.

Structural Equation Modeling: Initial Hypothesized Model and Measurement Model

The initial hypothesized conceptual model in Figure 1 includes the indicator variables for each latent construct and the predicted paths among latent variables. Traumatic events and HIV-related stigma were hypothesized to have a direct contributory effect on depression. Future orientation, perceived social support, and trusting relationships have a significant mediating effect on the relationships between traumatic events and/or HIV-related stigma and depression.

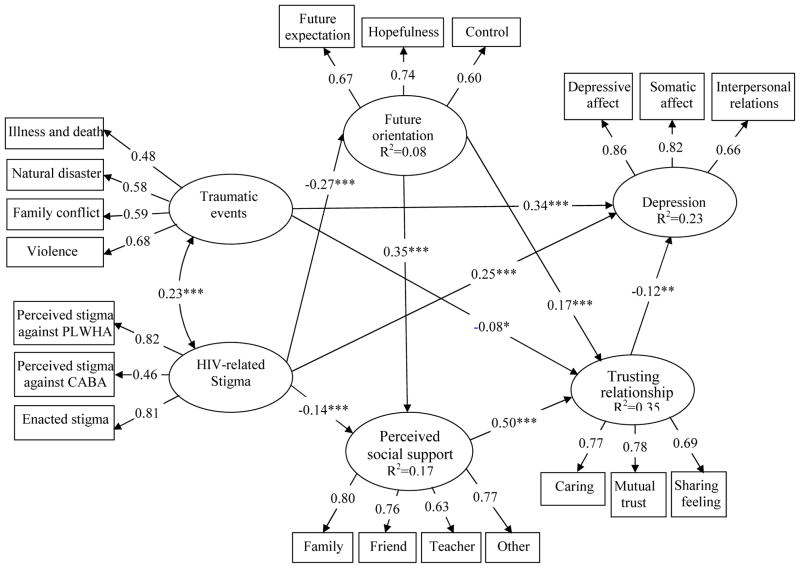

The measurement model consisted of 6 latent constructs and 20 indicator variables. Each of the 6 latent variables was measured by 3 or 4 manifest indicator variables. Based on the results from the measurement model, a few modifications were made to improve the model’s fit (e.g., one indicator variable-positive affect of depression was removed because its standardized factor loading was less than 0.20). The revised measurement model displayed in Figure 2 indicated a good fit with a chi-square/df of 3.93, a goodness-of-fit index (GFI) of 0.94, a root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.05, comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.93, and a non-normed fit index (NNFI) of 0.92. All factor loadings were substantial and significant (p<0.001), indicating that latent constructs were adequately explained by the manifest indicator variables.

Figure 2.

Measurement and structural model: Standardized factor loadings appear on the single-headed arrows connecting the latent and observed variables; Standardized path coefficients appear on the single-headed arrows connecting the latent variables; Correlation appears on curved double-headed arrow. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Structural Equation Modeling: Structural Model

The initial hypothesized model tested is shown in Figure 1, which includes 13 paths among latent constructs. Estimation of this model revealed a significant chi-square statistic and acceptable GFI and CFI values (greater than 0.90). In modifying the initial model, we eliminated five nonsignificant paths including the paths from traumatic events to future orientation and perceived social support, the path from HIV-related stigma to trusting relationships, and the paths from future orientation and perceived social support to depression. Wald tests suggested that the removal of these non-significant paths did not increase the model chi-square. The revised model was retained as the final structural model. The overall fit of the final model was good. The chi-square/df ratio was 3.71, the RMSEA was 0.05, the GFI was 0.94, the CFI was 0.93, and the NNFI was 0.92.

The final structural model with standardized path coefficients is presented in Figure 2. The effects of demographic variables (e.g., age, gender) that are associated with depression have been adjusted in the final model. Significant pathways depict associations between latent constructs. Traumatic events and HIV-related stigma had significant direct contributory positive effects on depression, with higher level of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma resulting in increased depression. Traumatic events were negatively associated with trusting relationship, which in turn was negatively associated with depression. HIV-related stigma was negatively related with future orientation and perceived social support, which in turn were positively related to trusting relationship. Thus, traumatic events had significant indirect effects on depression through trusting relationships; HIV-related stigma also had significant indirect effects on depression through future orientation, perceived social support and trusting relationships. In addition, HIV-related stigma was strongly correlated with traumatic events.

The Sobel test of mediation effects indicated that trusting relationships partially mediated the relationship between traumatic events and depression (z=1.97, p<0.05). In addition, the Sobel tests suggested that trusting relationships together with future orientation or perceived social support partially mediated the relationship between HIV-related stigma and depression (z=3.21 and z=2.59, p<0.01).

Discussion

This study tested a mediation model to evaluate both direct and indirect effects of the experience of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma on psychological well-being among children affected by HIV/AIDS. The study also identified several protective factors for psychological well-being. Consistent with findings from previous studies (Cluver et al., 2008; Suliman et al., 2009), our findings demonstrated that exposure to traumatic events and experience of HIV-related stigma were associated with higher levels of depression. The association appeared to be mediated by a trusting relationship with caregivers. Our final structural model also detected a dynamic interplay between future orientation, perceived social support and trusting relationships. This is consistent with the concept of the social ecological model which posits that complex problem behaviors are multiply determined and reflect difficulties with many systems in which the child and caregivers are embedded (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In this study, future orientation and perceived social support interact with trusting relationships with caregivers, which in turn affects psychological well-being. Trusting relationships appeared to be the most proximate protective factor for psychological well-being.

Given that trusting relationships with caregivers provides the most immediate source of psychological support for children affected by HIV/AIDS and has important long-term consequences for children’s wellbeing (Messer et al., 2010), future mental health promotion programs should focus on enhancing the relationship between the child and caregiver. As perceived social support and future orientation had direct positive effects on trusting relationships, future prevention programs should also seek to increase social support and to enhance the future expectations of children as they approach their early adolescence. Caregivers and teachers should instill hope and positive expectations for the future in children affected by HIV/AIDS. However, in order to design effective interventions to enhance future orientation and trusting relationships with caregivers, the identification of the factors that influence the development of future orientation and trusting relationships is necessary. Further, as guardianship planning can buffer the negative impact of parental death on the children (Cowgill et al., 2007; Lightfoot & Rotheram-Borus, 2004), clinicians and social service organizations may wish to discuss this issue and/or refer HIV-infected parents to resources, if available, that facilitate the guardianship planning process.

HIV-related stigma was found to have direct and indirect negative effects on children’s psychological well-being, which indicates a need for interventions to reduce HIV stigma in the general public and to help children to cope with stigma. Reviews of stigma reduction strategies suggest positive results of legal protection, provision of antiretrovirals, introduction of quality HIV care in reducing public fear of HIV (Castro & Farmer, 2005; Klein et al., 2002) and community interventions including provision of information about HIV, counseling , and contact with HIV+ people (Brown et al., 2003). In addition, our study provides clear evidence that an experience of traumatic events has an adverse impact on children’s mental health. Future interventions should seek to decrease children’s exposure to stressful events and to strengthen child and family resources for dealing with those stressors.

The current study has several potential limitations. First, despite the efforts to recruit participants from different settings (i.e., AIDS orphanages, small group homes, and families), the study sample may not be representative of children affected by AIDS in other areas of China because HIV infections in our research sites were mainly caused by unhygienic blood collection. The psychosocial issues and experiences of the children in our study may be different from those children whose parents were infected through other modes of transmission (e.g., drug use and sex). We anticipate that children whose parents were infected by HIV through drug use and sex might have experienced higher levels of social stigma and lower levels of social support compared to children whose parents were infected through unhygienic blood-selling. Second, the cross-sectional data precludes causal interpretations of our findings. Longitudinal research is needed to examine the causal relationship between the experience of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma and psychological well-being. Finally, internal consistency estimates (Cronbach alpha) were relatively low (e.g., less than 0.50) for some of the indicator variables (i.e., “illness and death” and “perceived stigma against CABA”) measuring latent constructs of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma. However, the application of structural equation modeling (SEM) may minimize the potential negative effects of low internal consistency of some indicator variables on the results, as SEM can reduce measurement errors by having multiple indicators per latent construct (Hatcher, 2005).

Despite these potential limitations, our findings can inform the development of interventions that promote care and psychological support of children affected by HIV/AIDS. First, our study demonstrated that multiple levels of protective factors interact with each other and mitigate the effect of traumatic events and HIV-related stigma on psychological well-being. This finding implies a need for mental health promotion programs for HIV-affected adolescents to adopt an ecological approach, strengthening protective influences at the individual, interpersonal, community levels. Second, as a trusting relationship is the most proximate protective factor for psychological well-being, it should be a focus and important goal for future prevention interventions seeking to improve the psychological well-being among children affected by HIV/AIDS. Finally, it is essential that interventions are developed to reduce stigma toward children affected by HIV/AIDS to alleviate their psychological problems.

Research highlights.

examines the relationships among several risk and protective factors regarding depression among AIDS orphans.

provides important information to guide the development of mental health interventions for AIDS orphans.

demonstrates that perceived social support, trusting relationships and future orientation offer multi-level protection for the mental health of orphans; and,

suggests that trusting relationships with caregivers provide the most immediate sources of psychological support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allgöwer A, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Depressive symptoms, social support, and personal health behaviors in young men and women. Health Psychology. 2001;20:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwine B, Cantor-Graae E, Bajunirwe F. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal S, Crombez G, Van Oost P, Debourdeaudhuij I. The role of social support in well-being and coping with self-reported stressful events in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1377–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Kennedy D, Ryan G, Murphy DA, Elijah J, et al. HIV-related stigma among people with HIV and their families: a qualitative analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:244–254. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 2. Vol. 2. New York: Basic Books, Inc; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Rocheleau CA, Robbins RN, Hutchinson KE. Condom use among high-risk adolescents: testing the influence of alcohol use on the relationship of cognitive correlates of behavior. Health Psychology. 2005;24:133–142. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan P, Morrissey J. Social support and health: a review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18:203–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18020203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Farmer P. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:53–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.028563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Qian X, Cao GH, Chen CK, Gao YN, Jiang QW. Study on the seropositive prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus in a village residents living in rural region of central China. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;25:317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Ministry of Health (MOH) and UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China. A joint assessment of HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in China. 2003 Retrieved May 8, 2010, from http://data.unaids.org/UNA-docs/china_joint_assessment_2003_en.pdf.

- Cluver LD, Gardner F, Operario D. Effects of stigma on the mental health of adolescents orphaned by AIDS. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D. Psychological distress amongst AIDS-orphaned children in urban South Africa. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver LD, Orkin M, Gardner F, Boyes ME. Persisting mental health problems among AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowgill BO, Beckett MK, Corona R, Elliott MN, Parra MT, Zhou AJ, et al. Guardianship planning among HIV-infected parents in the United States: results from a nationally representative sample. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e391–398. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker CL. Social support and adolescent cancer survivors: A review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2007;16:1–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Weissman MM, Warner V. Screening for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: validating the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;131:538–551. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Handbook of Attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. Loss and bereavement: Attachment theory and recent controversies concerning “grief work” and the nature of detachment. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald R, Rubin A. Brief assessment of children's post-traumatic symptoms: Development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Research on Social Work Practice. 1999;9:61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Haine RA, Ayers TS, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA. Evidence-based practices for parentally bereaved children and their families. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice. 2008;39:113–121. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine RA, Ayers TS, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Weyer JL. Locus of control and self-esteem as stress-moderators or stress-mediators in parentally bereaved children. Death studies. 2003;27:619–640. doi: 10.1080/07481180302894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L, editor. A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2005. pp. 141–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Li X, Fang X, Zhao G, Zhao J, Zhao Q, et al. Care arrangements of AIDS orphans and their relationship with children's psychosocial well-being in rural China. Health Policy and Planning. 2011;26:115–123. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Li X, Fang X, Zhao G, Lin X, Zhang J, et al. Perceived social support and psychosocial distress among children affected by AIDS in China. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9201-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaggwa EB, Hindin MJ. The psychological effect of orphanhood in a matured HIV epidemic: an analysis of young people in Mukono, Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Toefy Y, Cain D, Cherry C, et al. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SJ, Karchner WD, O'Connell DA. Interventions to prevent HIV-related stigma and discrimination: findings and recommendations for public health practice. Journal Public Health Management and Practice. 2002;8:44–53. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupnick JL, Green BL, Stockton P, Goodman L, Corcoran C, Petty R. Mental health effects of adolescent trauma exposure in a female college sample: exploring differential outcomes based on experiences of unique trauma types and dimensions. Psychiatry. 2004;67:264–279. doi: 10.1521/psyc.67.3.264.48986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Detels R, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Duan N. The effect of social support on mental and behavioral outcomes among adolescents with parents with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1820–1826. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Barnett D, Fang X, Lin X, Zhao G, Zhao J, et al. Lifetime incidences of traumatic events and mental health among children affected by HIV/AIDS in rural China. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:731–744. doi: 10.1080/15374410903103601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children: psychometric testing of the Chinese version. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66:2582–2591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Predictors of child custody plans for children whose parents are living with AIDS in New York City. Social work. 2004;49:461–468. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Barnett D. The relation between familial factors and the future orientation of urban, African American sixth graders. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2000;9:491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Pence BW, Whetten K, Whetten R, Thielman N, O'Donnell K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of HIV-related stigma among institutional- and community-based caregivers of orphans and vulnerable children living in five less-wealthy countries. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:504. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustillo SA, Dorsey S, Farmer EMZ. Quality of relationships between youth and community service providers: reliability and validity of the trusting relationship questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha EO, Wandibba S, Aagaard-Hansen J. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom RA, Serovich JM, Lim JY, Mason TL. The role of stigma in reasons for HIV disclosure and non-disclosure to children. AIDS Care. 2006;18:60–65. doi: 10.1080/09540120500161769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivnick A, Villegas N. Resilience and Risk: Childhood and Uncertainty in the AIDS Epidemic. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2000;24:99–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1005574212572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner D, Mfecane S. Stigma, discrimination and the implications for people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Journal SAHARA. 2004;1:157–164. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. Coping with stress: effective people and processes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Feldman DB, Taylor JD, Schroeder LL, Adams VH., III The roles of hopeful thinking in preventing problems and enhancing strengths. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2000;9:249–269. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman S, Mkabile SG, Fincham DS, Ahmed R, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Cumulative effect of multiple trauma on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ, Price AW, Williams K, Kingree JB. Role of secondary stressors in the parental death-child distress relation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:357–366. doi: 10.1023/a:1021951806281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Enhanced protection for children affected by AIDS. [Accessed December 12, 2010];2007 Available online: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Enhanced_Protection_for_Children_Affected_by_AIDS_Summary.pdf.

- UNICEF. Children and AIDS: Second stocktaking report. Geneva: UNAIDS, UNICEF, WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Weinfield NS, Hamilton CE. The stability of attachment security from infancy to adolescence and early adulthood: general discussion. Child Development. 2000;71:703–706. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, Clark LF. Reconceptualizing adolescent sexual behavior: beyond did they or didn't they? Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild L, Flisher A, Laas S, Robertson B. The psychosocial adjustment of adolescents orphaned in the context of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2006;17(2):87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Yan Z, Duan S, Wang C, Rou K, Wu Z. Psychosocial well-being of children in HIV/AIDS-affected families in southwest China: A qualitative study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhao G, Li X, Hong Y, Fang X, Barnett D, et al. Positive future orientation as a mediator between traumatic events and mental health among children affected by HIV/AIDS in rural China. AIDS care. 2009;21:1508–1516. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Hu D, Xi Y, Zhang M, Duan G. Spread of HIV in one village in central China with a high prevalence rate of blood-borne AIDS. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;10:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Li X, Fang X, Hong Y, Zhao G, Lin D, et al. Stigma against children affected by AIDS (SACAA): reliability and validity of a brief measurement scale. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1302–1312. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9629-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]