Many biologists and social scientists have noted that with the development of human culture, the biological evolution of Homo sapiens was usurped by socio-cultural evolution. The construction of artificial environments and social structures created new criteria for selection, and biological fitness was replaced by ‘cultural fitness', which is often different for different cultures and is generally not measured by the number of offspring. Moreover, the mechanism of socio-cultural evolution is different from the model of biological evolution that was proposed by Charles Darwin (1809–1882), and refined by many others. In essence, socio-cultural evolution is ‘Lamarckian' in nature—it is an example of acquired inheritance, as described by the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829)—because humans are able to pass on cultural achievements to the next generation.

Yet, the idea that cultural fitness has replaced biological fitness does not fully take into account the thousands of years of human biological evolution that occurred long before socio-cultural evolution, in its strictest sense, took its course. Modern Homo sapiens first appeared about 200,000 years ago; however, socio-cultural evolution only began about 10,000 years ago, when early hunter–gatherer societies began to change their simple forms of segmentary social differentiation during the so-called Neolithic revolution, which was mainly caused by the invention of agriculture and cattle breeding. In mathematical terms, one could say that human biological evolution created an attractor: a stable state impervious to change. Various mathematical models of biological evolution, namely the genetic algorithm (Holland, 1975), show that the generation of such an attractor is the usual result of evolutionary processes (Klüver, 2000). Nevertheless, socio-cultural evolution did not end biological evolution; in fact, for most of the time that Homo sapiens has existed, socio-cultural evolution has been so slow that it could not have affected biological evolution. Here, I attempt to explain why modern humans existed long before socio-cultural evolution really began.

What does socio-cultural evolution mean? There have been many attempts to define this ambiguous concept (Trigger, 1998), which have interpreted the term ‘evolution' in a literal sense and assumed that socio-cultural evolution is determined by the same mechanisms as its biological counterpart. It is true that the evolution of human societies and cultures shares some similarities with biological evolution, but in many respects these two are not the same. Therefore, at the outset, it is necessary to give a precise definition of evolution in the field of human societies (Klüver, 2002).

Socio-cultural evolution, as the name implies, has two dimensions: social and cultural. Some of the great social theorists of the last century defined ‘culture' in terms of the generally accepted knowledge of a certain society or social group (Habermas, 1981; Giddens, 1984). Under this definition, ‘knowledge' is not limited to natural and social phenomena, but includes, for example, religion, worldviews and moral values. Similarly, ‘accepted' does not imply that such knowledge is true according to scientific standards—for example, the Judaeo-Christian belief that God created the world—but only that it is accepted within one culture as ‘true'. The definition of ‘social' naturally refers to social structures. ‘Social' can be defined as the set of rules that govern all social interactions in a certain society. The separation of power into legislative, judicative and executive arms of government in modern democracies is such a rule, as is the rule to drive on the right-hand side of the road in most countries. In mathematical terms, we can then define a society (S) using the equation S = (St, C), where C refers to culture and St refers to social structure.

In essence, socio-cultural evolution is ‘Lamarckian' in nature […] because humans are able to pass on cultural achievements to the next generation

Culture and social structure are, of course, abstracts that cannot be quantified and must instead be translated into empirical categories—namely, observable actions by, and interactions of, social actors. In a meta-theoretical sense, this transforms the concepts of culture and social structure into an action theory because only individual actors can be the units of an empirical social science. The main concepts here are social roles and their occupants.

Consider, for example, the social role of a medical doctor. A doctor is characterized by his or her knowledge of disease diagnosis, how to choose appropriate therapies and how to tell the patient to follow the therapy. However, the role of the doctor is also defined by specific rules—the Hippocratic Oath, for example—and by specific laws about how to treat patients, or how to adhere to health insurance or national regulations. Similarly, the role of a university professor is defined by specific scientific knowledge and specific rules of interaction with respect to, for example, teaching, publishing and dealing with university administration. We can therefore define a social role (r) as r = (k, ru), where k is the role-specific knowledge and ru represents the role-specific rules of social interaction (Berger & Luckmann, 1966).

An individual in a society is a social actor when he or she occupies a specific social role, which is not necessarily a professional role. There are other social roles such as being a parent or being a member of a political party, and it is relatively easy to define the social rules and role-specific knowledge of these positions. Therefore, we can define a society as a web of social roles, the occupants of which interact according to the rules and to the knowledge that define these roles. A society is then produced and reproduced through the role-specific interactions of the role occupants. In many cases, the social structure and culture of a society merely reproduce—that is, they do not change notably. Yet, sometimes roles and interactions change markedly, and the social structure and culture change accordingly. Such times are called periods of reform or—in the extreme—revolutions.

…for most of the time that Homo sapiens has existed, socio-cultural evolution has been so slow that it could not have affected biological evolution

Now that we have defined what we mean by a society—based on culture and social structure—we can define socio-cultural evolution as the creation and change of social roles through new knowledge that changes and creates social rules. Socio-cultural evolution, then, alters and enlarges a society in the two dimensions of social structure and culture. The driving force is new ideas in the cultural dimension and the ensuing changes to the social structure that create new social rules of interaction. Social roles in a societal system therefore “become the equivalent of genes in a genetic system” (Read, 2005); however, this is only a formal equivalence, as the evolutionary mechanisms in these cases operate differently.

When we speak of social roles, we must make an important distinction. On the one hand, some social roles—those of artisans, craftspeople, artists, technicians, scientists or entrepreneurs, for example—are defined by ‘creative tasks', which expand the culture of society. Cultural evolution is therefore only possible if the occupants of creative roles enjoy a certain degree of freedom. On the other hand, there are roles—those of priests, politicians or teachers, for example—that serve to maintain social traditions, culture and social structures. We can call these ‘maintenance roles' in contrast to the ‘creative roles'. These are essential for the integration of a society because traditional norms and values allow a society to maintain its societal identity.

The crucial factor for the evolutionary potential of a society, then, is the relationship between creative roles and maintenance roles. If the maintenance roles have a strong influence on the creative roles, the occupants of creative roles cannot fulfil their creativity and the development of culture stagnates; a society gets caught in a cultural evolutionary attractor. The relationship between these two classes of roles is the decisive parameter for the evolutionary power of a society, which can be called an evolutionary parameter (EP) and determines the evolutionary fate of a society. The ultimately unsuccessful attempts of the Catholic Church to silence proponents of the heliocentric model of the planetary system—most notably Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) and Galileo Galilei (1564–1642)—is an example of an unfavourable EP. A society must have a certain degree of heterogeneity with respect to the existence of different roles and the social ‘distance' between the two kinds of roles. If a society is too homogeneous, socio-cultural evolution will stop sooner or later.

Looking at historical examples can validate this general hypothesis about the logic of socio-cultural evolution. Starting in the fourteenth century, the European nations entered a period characterized by reforms, revolutions and scientific progress—known respectively as the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Enlightenment—and eventually evolved into modern Western societies. The technological and social competitors of Europe during the Middle Ages—notably feudal China and the Islamic societies—did not change in the same way because they did not have the EP values of European societies, despite the fact that they were culturally and scientifically more advanced than feudal Europe. The main reason for this was that the occupants of creative roles in Europe enjoyed a larger degree of freedom than those in rival societies (Klüver, 2002; Needham, 1970). In particular, the large trading cities of the Hanse, the Flemish cities and the cities of Northern Italy were centres of cultural growth with a certain political autonomy. This environment gave the occupants of creative social roles the benefit of greater freedom from the feudal political powers and the Catholic Church. This political and social structure had no parallels in the other great cultures.

On the basis of this hypothesis, our research group constructed mathematical models of socio-cultural evolution, the so-called socio-cultural algorithm (SCA) and the expanded socio-cultural cognitive algorithm (SCCA). These are multi-agent systems that consist of artificial actors. Each actor is represented by a combination of different neural nets, and the social relations between the actors are modelled by a cellular automaton and a Boolean net (Klüver, 2002; Klüver et al, 2003). Each actor is able to occupy a certain social role, can learn from others and can generate new ideas—of course, in an idealized and simplified manner. The sum of all the ideas that these actors generate is the level of the respective culture. According to the general evolutionary hypothesis, the actors, if they occupy a creative role, develop new ideas in proportion to the influence of the occupants of maintenance roles. We ran the models with different EP values and different numbers of actors ranging from 100 to more than 1,000,000. One important result was that the number of actors had no significant impact on the results—the evolutionary logic operated in small or large artificial societies.

Social roles in a societal system therefore “become the equivalent of genes in a genetic system”…

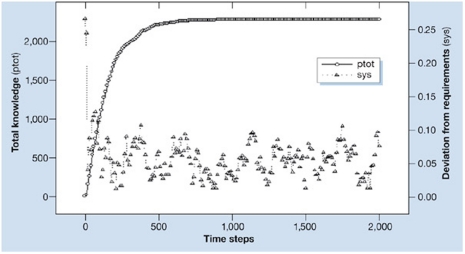

One typical result that we observed was a so-called Toynbee development, named after the British historian Arnold Toynbee (1889–1975) who showed that this is the fate of all known cultures (Toynbee, 1934–39; Fig 1). This artificial culture grows quickly but eventually slows down and stagnates. Most EP values led to this development in our simulations, which shows, at least in part, the significance of EP values and provides an explanation for the historical processes.

Figure 1.

A Toynbee development.

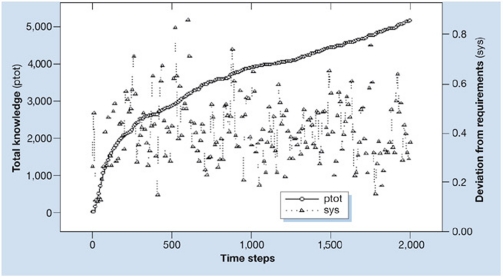

Only a few evolutionarily favourable EP values were able to generate a different image (Fig 2). In these cases, the artificial culture did not stop, but was able to continue to advance its cultural growth for as long as it existed. This might be the fate of Western culture, as its growth, particularly in science and technology, shows no detectable limits at present. Again, the reason for this is the decisive role of the EP and the relatively large degree of freedom that the occupants of creative roles enjoy in the West. In addition, we assume that the EP values themselves changed during European cultural development because the current values are even more favourable than those during the Medieval Ages. In other words, the EP values start a process of socio-cultural evolution and are themselves changed by this process—an evolution of evolution.

Figure 2.

A Western development.

The general hypothesis about socio-cultural evolution, the historical data and our simulations can apparently explain human history as an evolutionary process. In particular, they can explain the special path of European and, subsequently, Western culture. They might also answer the question raised at the beginning of this article: why did it take such a long time before socio-cultural evolution started at the beginning of the Neolithic revolution?

Early hunter–gatherer societies, or segmentary differentiated tribal societies as they are called in sociology, are homogeneous. There is little differentiation of social roles, which are mostly based on gender and age. The creative potential of these early humans could not unfold; small degrees of labour division did not allow for special roles and a common worldview of animistic religions further hindered individual thinking. It took a long time for these societies to become sufficiently heterogeneous to generate the creative achievements of the Neolithic revolution, which, in turn, changed the social structure of societies. The segmentary differentiated societies became stratified into social hierarchies and allowed a significant division of labour. Yet it took a long time to achieve this stage of socio-cultural evolution—and many tribal societies did not reach it at all—because only small processes of differentiation took place and creative individuals could only slowly create new ideas in their respective society. The long period of time between the biological emergence of Homo sapiens and the Neolithic revolution was necessary to allow these slow processes to generate a sufficiently heterogeneous society that could move to the next step in the evolutionary process. In other words, the Neolithic revolution could only take place when some societies were sufficiently differentiated to allow for individual creative processes. Moreover, it can be assumed that the initial EP values of the tribal societies did not significantly change with the slow growth of human culture.

The decisive question is, of course, whether this model of socio-cultural evolution can help us to make some educated guesses about the possible future of mankind. Will the process of globalization lead to a world culture that is characterized by the Western way? In theoretical sociology, we call this the hypothesis of universal modernization, which implies that only Western societies are truly modern ones and that the process of modernization will change all societies until they become modern in the Western sense, albeit with local variants. This classical hypothesis dates back to the Enlightenment, and was formulated in its most influential form by the social theorists Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Max Weber (1864–1920). Of course, the universal modernization hypothesis was, and still is, much discussed and criticized, in particular for being Eurocentric. One of the most famous critiques was made by the American political scientist Samuel Huntington in his bestseller The Clash of Civilizations (Huntington, 1996). Although I cannot discuss this and other criticisms of the modernization hypothesis for reasons of space, I can provide empirical data to validate the hypothesis, and make a methodical proposal based on the model of socio-cultural evolution and the SCCA program.

…the social future of mankind is probably a global society based on the traditions of Western societies with local adaptations

The European, and eventually Western, process of modernization is characterized by certain economic, political, educational and gender-based criteria that are indicators of modern development. If we apply these criteria to the developmental processes in different countries, we can detect astonishing parallels to Western history (Oesterdiekhoff, 2003). The economical relevance of the agrarian sector is decreasing in developing countries, even in Africa, whereas industry is gaining in importance. The same trend is valid for urbanization processes: in all developing countries, the rural population is decreasing as large cities emerge, just as happened in Europe in the eighteenth century. In most places, birth rates are also steadily declining—a trend that has been observed in Western countries since the nineteenth century. The mean marriage age of women is rising, which is certainly one cause of the decline in the birth rate and an important indicator of an increasing degree of female autonomy. The average number of democratic or semi-democratic societies is increasing—in which ‘democratic' means adopting the Western model of a parliamentary democracy. The levels of literacy and the number of participants in higher education are increasing in most countries, and many rapidly developing countries are investing massively in science and technology—not only large nations such as China and India, but also various South American countries. All of the trends that are now visible in developing countries were seen previously in Europe and North America as they progressed towards modern Western culture.

Although there are certainly other factors at work, this selection shows that many countries that are on their way to modernization follow the path of Western societies. Even politically regressive processes, for example the rise of Islamic theocracies, are expected—indeed, European countries experienced regressive fascist movements or periods of stagnation. Modernization as a form of socio-cultural evolution is not a linear process. As a preliminary summary, it seems that Marx, Weber and the other adherents of the universal modernization theory are right. At least, the data are more compatible with the universalistic theory of modernization than with its rivals.

Furthermore, our SCCA model provides support for this theory. The theoretical foundation of the model is the assumption that socio-cultural evolution depends on an increasing degree of role autonomy in important social domains. In particular, this assumption can explain the fact that the process of modernization emerged in Europe before it became the core of Western culture. If these theoretical and mathematical assumptions are correct, the validity of the universalistic theory of modernization—the question of the final socio-cultural character that will result from globalization processes—can be analysed in a twofold manner.

Empirical data from developing countries indicate that there is a growing trend in favour of role autonomy—again referring to gender roles and the rise of higher education. Overall, women are becoming more autonomous, and education is emancipating itself from religious and political influences in developing countries. Again, women's rights and the introduction of universal education marked important points in the history and development of Western countries. Such data can then be inserted into simulations, such as our SCA or SCCA, to predict roughly the probable development of these countries. Clearly, even such micro-sociologically based simulation programs can only give predictions about probable developments, but this is still better than a ‘best guess' or wishful thinking.

In any case, the future of our species depends on more factors than can be covered in this article. Yet, the social future of mankind is probably a global society based on the traditions of Western societies with local adaptations. Neither China nor India will become a mirror of the USA, but similarly neither Germany nor France is such a mirror. In the end, I believe, Marx and Weber will be proved right.

Jürgen Klüver

References

- Berger P, Luckmann T (1966) The Social Construction of Reality. New York, NY, USA: Doubleday [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A (1984) The Constitution of Society. Outlines of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press [Google Scholar]

- Habermas J (1981) Theorie des Kommunikativen Handelns, Vol. 2. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp [Google Scholar]

- Holland JR (1975) Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: University of Michigan Press [Google Scholar]

- Huntington SP (1996) The Clash of Civilizations. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster [Google Scholar]

- Klüver J (2000) The Dynamics and Evolution of Social Systems. New Foundations of a Mathematical Sociology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer [Google Scholar]

- Klüver J (2002) An Essay Concerning Sociocultural Evolution. Theoretical Principles and Mathematical Models. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer [Google Scholar]

- Klüver J, Malecki R, Schmidt J, Stoica C (2003) Sociocultural evolution and cognitive ontogenesis. A sociocultural cognitive algorithm. Comput Math Organ Theor 9: 255–273 [Google Scholar]

- Needham J (1970) Clerks and Craftsmen in China and the West. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Oesterdiekhoff GW (2003) Entwicklung der Weltgesellschaft. Hamburg, Germany: Lit [Google Scholar]

- Read D (2005) Change in the form of evolution. Transitions from primate to hominid forms of social organization. J Math Sociol 29: 91–114 [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee A (1934) A Study of History (12 Vols). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Trigger BG (1998) Sociocultural Evolution. New Perspectives on the Past. Oxford, UK: Blackwell [Google Scholar]