Abstract

We generated a mouse model for hemophilia A that combines a homozygous knockout for murine factor VIII (FVIII) and a homozygous addition of a mutant human FVIII (hFVIII). The resulting mouse, having no detectable FVIII protein or activity and tolerant to hFVIII, is useful for evaluating FVIII gene-therapy protocols. This model was used to develop an effective gene-therapy strategy using the φC31 integrase to mediate permanent genomic integration of an hFVIII cDNA deleted for the B-domain. Various plasmids encoding φC31 integrase and hFVIII were delivered to the livers of these mice by using hydrodynamic tail-vein injection. Long-term expression of therapeutic levels of hFVIII was observed over a 6-month time course when an intron was included in the hFVIII expression cassette and wild-type φC31 integrase was used. A second dose of the hFVIII and integrase plasmids resulted in higher long-term hFVIII levels, indicating that incremental doses were beneficial and that a second dose of φC31 integrase was tolerated. We observed a significant decrease in the bleeding time after a tail-clip challenge in mice treated with plasmids expressing hFVIII and φC31 integrase. Genomic integration of the hFVIII expression plasmid was demonstrated by junction PCR at a known hotspot for integration in mouse liver. The φC31 integrase system provided a nonviral method to achieve long-term FVIII gene therapy in a relevant mouse model of hemophilia A.

Chavez and colleagues report on a gene therapy strategy wherein the uC31 integrase is used to mediate permanent genomic integration of human coagulation factor VIII (hFVIII) cDNA. Plasmids encoding uC31 and hFVIII were administered intravenously to mice defective in murine factor VIII and tolerant to hFVIII. Long-term expression of therapeutic hFVIII levels was observed over 6 months, and bleeding time after tail-clip challenge was significantly decreased.

Introduction

Hemophilia A is an X-linked recessive disease caused by a deficiency of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) activity within the blood. It is the most common form of hemophilia, as it affects an estimated one in 5,000 males and accounts for 80–85% of the cases of hemophilia (Cooper and Tuddenham, 1994). Of 1,221 unique mutations identified in the human FVIII (hFVIII) gene, 47.7% were missense, the largest category. Of the remaining mutations, 16.1% were small deletions, 11.1% were large deletions, 10.7% were nonsense, 7.8% were splicing mutants, and 6.6% were insertions (Kemball-Cook et al., 1998). The levels of hFVIII in circulation determine the severity of the disease, with plasma levels 5–25% of normal being mild, 1–5% being moderate, and <1% being severe (Brettler, 1995). Therefore, only modest levels of circulating hFVIII are needed to be therapeutic and to provide protection from spontaneous bleeding episodes. Current treatments for hemophilia A include infusion of plasma-derived hFVIII, which carries with it the risk of infection, and administration of recombinant hFVIII, which is expensive (∼$100,000/year) and unavailable in most of the world.

These limitations of current treatments have stimulated research into alternative therapies for hemophilia A. Several animal studies using gene therapy have been encouraging. However, clinical trials have been unable to achieve long-term, therapeutic levels of hFVIII (Mátrai et al., 2010; Petrus et al., 2010). These failures have been due to factors such as immune responses to viral vectors (Chuah and VandenDriessche, 2004) and low and/or transient hFVIII gene expression (Roth et al., 2001; Powell et al., 2003). Additionally, current FVIII knockout mouse models have unfortunately been shown reproducibly to generate FVIII inhibitory antibodies after multiple injections of hFVIII (Qian et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2001). Inhibitory antibodies occur in only 25–30% of human hemophilia A patients who receive hFVIII infusions (Hoyer and Scandella, 1994). These patients may need special procedures, such as tolerization to hFVIII, before gene therapy can be used or, alternatively, introduction of activated factor VIIa (Gabrovsky and Calos, 2008).

The φC31 integrase is a site-specific recombinase native to bacteriophge φC31 of Streptomyces soil bacteria. In nature, φC31 integrase catalyzes the recombination of the viral genome with that of the bacterial host through two ∼30-bp recognition sequences termed attB and attP (Kuhstoss and Rao, 1991; Rausch and Lehmann, 1991; Groth et al., 2000). The integration reaction takes place without a requirement for any host cofactors (Thorpe and Smith, 1998). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that φC31 integrase autonomously catalyzes its recombination reaction in mammalian cells (Groth et al., 2000). Database searches have revealed that the mouse and human genomes do not contain perfect attP sites. They do, however, contain sites with similar sequences, termed pseudo attP sites (Thyagarajan et al., 2001). Integration of a plasmid bearing a therapeutic gene can be carried out by placing an attB site on the plasmid, cotransfecting with a plasmid encoding the φC31 integrase, and using integration into these native pseudo attP sites. Because φC31 integrase requires a relatively long and specific recognition sequence, the number of potential integration sites may be lower than in systems that integrate with less sequence specificity (Chalberg et al., 2006).

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructs

The φC31 integrase plasmids pVI, pVhP2, and pVmI were described previously (Keravala et al., 2009). The human B-domain–deleted FVIII cDNA was amplified from the vector pCAGEN/HSQ (kind gift of P. Lollar, Emory University) with the primers HSQ Forward (5′-ATGCAAATAGAGCTCTCCACCTGC-3’) and HSQ Reverse (5′-TCAGTAGAGGTCCTGTGCCTCGC-3’). PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min; then 94°C for 20 sec, 55°C for 20 sec, and 72°C for 3 min, repeated for 30 cycles; and a final hold at 4°C. The resulting 4.3-kb band was cloned into the Topo TA cloning vector from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The human factor IX expression plasmid pVB9 (Keravala et al., 2009) was cut with NruI/EcoRV, removing the factor IX gene. The hFVIII gene was then cloned in using the same restriction enzymes, creating pVB8. To create pVB8ii, the factor IX intron A from pVB9 was introduced into the native FVIII intron-1 location using an enzyme-free cloning method (Tillett and Neilan, 1999).

Mice

Mice were housed in the Research Animal Facility at Stanford University. huFVIII-R593C mice have been described previously (Bril et al., 2006). In brief, an huFVIII-R593C expression cassette was injected into fertilized oocytes of FVB mice. Founder mice were then crossed to C57BL/6 mice for five generations. These mice were then crossed to FVIII knockout mice (B6;129S4-F8tm1Kaz/J) that carry a targeted disruption of exon 16 of the mouse FVIII gene (Bi et al., 1995), purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were fed water and chow ad libitum. Eight- to 10-week-old mice were used for the studies. Experimental protocols were approved by the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care at Stanford University. Hydrodynamic tail-vein injection in mice was carried out as described (Keravala et al., 2009).

Genomic DNA isolation

To obtain mouse-tail DNA, after clipping of 1 cm of a mouse tail, the intact end of the mouse tail was cauterized with Kwik Stop Styptic Powder (Gimborn Pet Specialties, Atlanta, GA). DNA was isolated as described previously (Laird et al., 1991). To obtain mouse liver DNA, mouse livers were dissected, and different lobes of the liver were minced. Approximately 25 mg of liver tissue was used for genomic DNA isolation using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA).

Genotyping PCR

Mice were screened for the mutant hFVIII transgene by PCR. DNA (100 ng) obtained from mouse tails was used as template to generate a 505-bp fragment. The primers used were HF8F (5′-GAATTCAGGCCTCATTGGAG) and HF8R (5′-TCGTAGTTGGGGTTCCTCTG). PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min; then 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, repeated for 30 cycles; and a final hold at 4°C.

hFVIII activity, expression, and Bethesda assays

Blood was collected by retro-orbital puncture using capillary tubes and transferred to microfuge tubes containing sodium citrate to a final concentration of 0.38% (vol/vol). The blood was then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 20 min, and the plasma was removed and stored at −80°C until use. hFVIII activity in mouse plasma was determined using the Biophen FVIII:C kit from Hyphen BioMed (Neuville-sur-Oise, France), following the manufacturer's protocol. hFVIII concentration was determined using the Matched-Pair Antibody Set for ELISA of hFVIII antigen, following the manufacturer's protocol (Affinity Biologicals, Ancaster, ON, Canada). FVIII inhibitor antibodies were determined as described previously (Jin et al., 2004), with the following modification: Residual FVIII activity was determined using the Biophen FVIII:C kit from Hyphen BioMed. Pooled human plasma from Instrumentation Laboratory (Lexington, MA) was used to generate standard curves.

Mouse-tail bleeding

We used a method of tail bleeding described previously (Gui et al., 2009), with a few modifications. In brief, mice were anesthetized with ketamine xylazine. The tail was transected at 1 cm from the tip and immersed in 14 ml of HBSS at 37°C. The time to cessation of bleeding was recorded. After 10 min, bleeding was stopped by applying pressure to the tip of the tail.

Pseudo site PCR

φC31 integrase–mediated integration was confirmed by PCR at the mpsL1 pseudo attP site (Olivares et al., 2002). The first round of amplification was performed with primers attB-F3 (5′-CGAAGCCGCGGTGCG) and mpsL1-R1 (5′-GTAAATGTTATTGCGGCTCT). The second round was performed with primers attB-F4 (5′-CGGTGCGGGTGCCA) and mpsL1-R2 (5′-GGTCATGGAGCCCCTTCACAA). Both rounds used the following PCR conditions: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min; then 94°C for 30 sec, 66°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 20 sec, repeated for 30 cycles; a final extension at 72°C for 3 min; and a final hold at 4°C.

Southern-blot analysis

Southern blots were used to determine whether mice were singly or doubly transgenic for the mutant hFVIII gene. A probe was generated to the mutant hFVIII gene by PCR of a known transgenic mouse. The following primers were used: HF8F (5′-GAATTCAGGCCTCATTGGAG) and HF8R (5′-TCGTAGTTGGGGTTCCTCTG). The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min; then 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, repeated for 40 cycles; and a final hold at 4°C. A 505-bp fragment of the mutant hFVIII gene was amplified. Eight micrograms of total liver DNA were digested with BamHI-HF. The samples were then electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The mutant hFVIII transgene was detected after hybridization with a digoxigenin-labeled hFVIII probe and chemiluminescence (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). A 1.9-kb band was detected in transgenic mice. The band was twice as dark in double-transgenic mice as in single-transgenic mice.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Microsoft Excel program. The one-tailed Student's t test assuming unequal variances was used to analyze significant differences between groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Generation of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice

We used a mouse that was a transgenic knockin for the hFVIII R593C missense mutation (Bril et al., 2006). This mutation was identified in 48% of patients with mild hemophilia A in a past study (Bril et al., 2004). We chose this mouse model because it had been demonstrated to be tolerant to hFVIII under normal conditions and, importantly for gene-therapy studies, was also shown to have no detectable FVIII activity or circulating protein by ELISA in mice (Bril et al., 2006). We crossed this mouse to an FVIII E-16 knockout mouse (Bi et al., 1995), creating a strain that was murine FVIII-null and tolerant to hFVIII (huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO). This mouse was then bred to homozygosity, as confirmed by PCR and Southern blot (Fig. 1). This strain was used in all of the following studies.

FIG. 1.

Generation of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice. (A) Breeding diagram shows how homozygous huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice were generated for use in the study. (B) PCR was conducted on tail DNA using primers that specifically amplify the hFVIII gene present in transgenic mice. Lanes 1–5, samples from experimental mice showing that mice 1 and 3–5 are positive for the hFVIII gene. MW, molecular weight ladder; +, positive control; −, negative control mouse DNA. (C) Southern blot of tail DNA digested with BamHI and hybridized to a 505-bp hFVIII probe. Lane 1, negative control (−/−); lanes 2–8, samples from experimental mice, showing that mice 2 and 6–8 were homozygous (+/+) and mice 3–5 were heterozygous (+/−).

Hydrodynamic injection of an hFVIII expression plasmid leads to long-term circulating hFVIII activity

The hFVIII expression plasmid pVB8 carries the B-domain–deleted hFVIII cDNA under the control of the liver-specific human α1-antitrypsin promoter and apolipoprotein E enhancer (Miao et al., 2000) (Fig. 2). Additionally, pVB8 carries the φC31 integrase attB site for genomic integration. pVB8 was injected along with a φC31 integrase expression plasmid (20 mg each) into the livers of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice by hydrodynamic injection. Three different φC31 integrase expression plasmids were used in this study. pVI expresses the wild-type φC31 integrase that has been used in most gene-therapy studies. pVhP2 expresses a mutant φC31 integrase shown to have increased integration activity in vitro and in vivo in C57BL/6 mice (Keravala et al., 2009), and was tested to determine whether it conferred an advantage. pVmI expresses a catalytically inactive form of the integrase enzyme (Keravala et al., 2009) and represented a negative control.

FIG. 2.

φC31 integrase and hFVIII plasmids. pVI, the pVax backbone carrying the coding sequence for wild-type φC31 integrase under control of the cytomegalovirus promoter; pVhP2, a higher-efficiency φC31 integrase mutant; pVmI, pVax carrying an inactive mutant integrase; pVB8, liver-specific hFVIII plasmid; pVB8ii, liver-specific hFVIII plasmid containing an intron. The hFVIII plasmids contain the pVax backbone, φC31 integrase attB site, human α1-antitrypsin (hAAT) promoter, B-domain–deleted hFVIII cDNA, with or without an intron, and the bovine growth hormone polyA sequence.

Following coinjection of pVB8 with pVI, pVhP2, or pVmI, plasma was collected from treated mice over a time course, and hFVIII activity was determined (Fig. 3). In mice that received pVB8 with pVI, pVmI, or no integrase, the hFVIII activity levels declined gradually over the first 2 months of the experiment, then stabilized at relatively low values. However, animals injected with the pVhP2 mutant form of φC31 integrase (pVhP2) displayed a rapid drop in hFVIII activity, with most animals having no detectable hFVIII activity by 4 weeks post injection. At the last time point (day 168), there was no significant difference overall between groups that received pVI and groups that received either pVmI or no integrase plasmid. The percentages of mice expressing hFVIII, as well as the hFVIII activity levels, are presented in Table 1.

FIG. 3.

hFVIII activity in plasma of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice injected with various plasmids. Mice were hydrodynamically injected with pVB8 alone, pVB8+pVmI, pVB8+pVI, pVB8+pVhP2, or a saline solution only. Plasma samples were assayed for hFVIII activity at the time point indicated. Expression of hFVIII was measured by activity assay. Values are means±SEM.

Table 1.

Frequency of Mice Having hFVIII Activity After Injection of pVB8 and Various Integrase Plasmids at the Final Time Point (Day 168)

| Treatment | Frequency | hFVIII activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| pVB8 | 2/6 (33%) | 2.8–9.7 |

| pVB8+pVmI | 1/6 (17%) | 0–7.0 |

| pVB8+pVI | 4/7 (57%) | 5.3–18.6 |

| pVB8+pVI x2 | 10/10 (100%) | 7.5–49.8 |

In an attempt to increase hFVIII expression, an additional dose of pVB8+pVI was administered to a separate group of mice 30 days subsequent to the first injection. Plasma was collected over a time course and hFVIII activity measured. Mice that received a second dose of pVB8+pVI displayed significantly higher hFVIII activities at all time points following the second injection, when compared with mice receiving a single injection (Fig. 4). All mice receiving two injections of pVB8+pVI exhibited hFVIII activity at the last time point (day 168) and had a range of expression of 7.5–49.8% (Table 1). By contrast, only 57% of mice receiving a single injection of pVB8+pVI expressed hFVIII at the end of the study and had a range of expression of 5.3–18.6%. Mice that received an injection of saline displayed no hFVIII activity at any time point tested.

FIG. 4.

hFVIII activity in plasma of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice injected with a single injection of pVB8+pVI, versus two injections of pVB8+pVI. Plasma samples were assayed for hFVIII activity at the time point indicated. Arrow indicates when the second injection was administered (day 30). Expression of hFVIII was measured by activity assay through the length of the study. Values are means±SEM. Asterisks denote values that differ statistically from a single dose of pVB8+pVI: **p<0.05 (Student's t test).

It has been shown that the addition of an intron to a cDNA can lead to enhanced protein expression (Choi et al., 1991). To test whether hFVIII expression could be increased in this fashion, an intron was added to the hFVIII cDNA, creating the plasmid pVB8ii (ii=internal intron; Fig. 2). This plasmid, along with pVI, was injected into huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice. Plasma samples were collected over a time course, and the hFVIII activity was determined (Fig. 5A). Mice receiving pVB8ii+pVI displayed higher hFVIII activities at all time points tested, compared with the pVB8ii-only treated cohort. At day 140, all mice in the pVB8ii+pVI group had hFVIII activities of 72.7–301.2%. Within the pVB8ii-only group, 83.3% of the mice maintained hFVIII expression of 17.0–119.4%, whereas 71.4% of the animals in the pVB8ii+pVmI group expressed hFVIII in the range of 11.7–186.1%. As pVB8ii resulted in much higher levels of hFVIII expression as compared with pVB8, pVB8ii was used throughout the remainder of the study.

FIG. 5.

hFVIII activity, concentration, and bleeding times of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice injected with various plasmids. Mice were hydrodynamically injected with pVB8ii alone, pVB8ii+pVmI, pVB8ii+pVI, pVB8+pVI, or a saline solution only. Plasma samples were assayed for hFVIII activity by activity assay and for expression by ELISA at the time points indicated. (A) Percentages are plotted of hFVIII activity from all groups throughout the experiment. Arrow denotes time point when a single carbon tetrachloride injection was given. Values are means±SEM. Asterisk denotes values that differ statistically from the pVB8ii only group: *p<0.05 (Student's t test). (B) hFVIII expression was assayed by ELISA at various time points. Arrow denotes time when a single carbon tetrachloride injection was given. Negative control animals were injected with a saline solution. Values are means±SEM. Asterisk denotes values that differ statistically from the pVB8ii only group: *p<0.05 (Student's t test). (C) Bleeding times following tail clip of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice injected with various plasmids. Bleeding time was monitored over a 10-min time period. Asterisks denote values that differ statistically from pVB8ii+pVI: *p<0.05 or **p<0.005 (Student's t test).

To eliminate unintegrated pVB8ii and reveal the hFVIII activity due to integrated pVB8ii only, a single injection of carbon tetrachloride was administered to all mice on day 154. Carbon tetrachloride is known to induce cycling of hepatocytes and to cause unintegrated plasmid DNA to be lost (Liesner et al., 2010). In animals that received pVB8ii alone or pVB8ii+pVmI, hFVIII activity levels fell below detection limits by 2 weeks post carbon tetrachloride treatment. In three of the four animals that received φC31 integrase, hFVIII expression was maintained after exposure to carbon tetrachloride, albeit at reduced levels. Two additional plasma samples were collected from the mice post carbon tetrachloride treatment, and the hFVIII activity was measured. Three of the four mice in the pVB8ii+pVI group continued to express hFVIII over the next 28 days at levels significantly higher (p<0.05) than mice that received no functional φC31 integrase (Table 2). None of the mice without integrase expressed any hFVIII post carbon tetrachloride treatment.

Table 2.

Frequency of Mice Having hFVIII Activity After Injection of pVB8ii and Various Integrase Plasmids at Time Points Before (Day 140) and After (Day 196) Carbon Tetrachloride Injection

| Treatment | Frequency (day 140) | hFVIII activity (%) | Frequency (day 196) | hFVIII activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pVB8ii | 5/6 (83%) | 6.9–119 | 0/0 | 0.0 |

| pVB8ii+pVmI | 6/7 (86%) | 11.7–186 | 0/0 | 0.0 |

| pVB8ii+pVI | 4/4 (100%) | 26.1–301 | 3/4 (75%) | 52.7–129 |

φC31 integrase–mediated integration provides sustained therapeutic levels of hFVIII expression in huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice

To determine the levels of circulating hFVIII, the previously collected blood samples were also subjected to hFVIII ELISA (Fig. 5B). On day 2 post injection, all animals displayed high levels of circulating hFVIII, ranging from 10.0 to 96.2 ng/ml. The initially high hFVIII levels dropped for all groups, with the groups without active φC31 integrase falling most rapidly. The hFVIII levels in mice that received pVB8ii+pVI plateaued after 28 days and remained constant through day 140; the hFVIII levels were significantly higher than the levels of other groups during most of the time course (days 14, 28, 84, 140, 168, 182, and 169; p<0.05). Animals that received either pVB8ii alone (5.7±3.2 ng/ml) or pVB8ii+pVmI (7.9±2.8 ng/ml) exhibited four- and threefold lower expression of hFVIII, respectively, compared with those receiving pVB8ii+pVI (22.4±7.1 ng/ml) at day 140 post injection.

To determine the proportion of hFVIII in circulation due to expression from integrated pVB8ii only, a single injection of carbon tetrachloride was administered to all mice at day 154, using the same mice as in Fig. 5A. Mice that received pVI maintained hFVIII expression, whereas those that did not receive pVI had no detectable hFVIII 14 days after carbon tetrachloride injection (day 168; Fig. 5B). Mice receiving pVI showed a small decrease in hFVIII levels after treatment. However, these levels stabilized and were within the therapeutic range for the remainder of the experiment (196 days).

huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice treated with φC31 integrase and an hFVIII plasmid displayed hemostatic protection in a bleeding assay

To determine if treated mice were hemostatically protected from a bleeding challenge, a tail-clip assay was performed at 196 days post injection. Protection was determined by measuring bleeding during a 10-min time period after having 1 cm of the tail clipped. Mice treated with pVB8ii+pVI bled for a significantly shorter time than mice treated with pVB8ii alone or pVB8ii+pVmI, or huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO control mice (p<0.005) (Fig. 5C). Although hemoglobin was not measured, we observed that total blood loss correlated well with bleeding time across all groups tested. C57BL/6 mice were used as a general positive control for normal bleeding time and had a significantly shorter bleeding time than huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice treated with pVB8ii+pVI (p<0.05). These data indicate that treatment with pVB8ii+pVI reduced the bleeding time of huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice, although not to fully wild-type (C57BL/6) levels.

Because they possess a transgenic copy of a mutated hFVIII gene, the mice used in this study were not expected to develop inhibitory antibodies when exposed to hFVIII, as previously reported (Bril et al., 2006). To confirm these results, we conducted a Bethesda inhibitor assay over the time course of day 28 through day 168 post treatment (Fig. 6). Results of this assay revealed no detectable anti-hFVIII inhibitor antibodies, because none of the treated samples displayed any significant difference in antibody titers from naive mouse plasma. By contrast, control plasma known to contain hFVIII inhibitors displayed a significant level of hFVIII inhibition when compared with naive mouse plasma in the assay (p<0.005; Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Immune response to hFVIII. Immune response to hFVIII was measured by Bethesda assay on four huFVIII-R593C/E-16KO mice injected with 20 mg each of pVI+pVB8ii and an uninjected naive control. Mice were injected with plasmid DNA via hydrodynamic tail-vein injection, and plasma samples were collected at the times indicated. Asterisks denote values that differ from the naive group: **p<0.005 (Student's t test).

Detection of genomic integration within the livers of treated mice

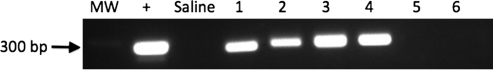

To determine whether φC31 integrase mediated genomic integration within hepatocytes, we carried out PCR analysis at a specific, known integration site commonly used by integrase in mouse liver. Although φC31 integrase mediates plasmid integration at many different genomic loci, several studies have demonstrated that φC31 integrase has a preferred integration site within the mouse genome that is preferentially used in liver (Olivares et al., 2002; Held et al., 2005; Keravala et al., 2009). Therefore, this site represents a convenient assay for the existence of site-specific integration, even though it represents only one of many possible integration sites. This locus is on chromosome 2 and is termed the mouse pseudo site L1 (mpsL1). Plasmid integration can be demonstrated at this locus by detection of a specific PCR band that represents the junction between the chromosomal mpsL1 site and a portion of the plasmid attB site. At the termination of the experiment, genomic DNA was isolated from the livers of mice from different groups, and 100 ng was used to amplify the integration junction. A PCR band indicating integration of pVB8ii was detected in all mice that received an injection of pVBii+pVI, whereas mice receiving either pVB8ii alone or pVB8ii with pVmI did not show the presence of this band (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Genomic integration of pVB8ii into a genomic pseudo attP site in mouse liver. PCR demonstrates genomic integration of pVB8ii at a preferred pseudo attP site (mpsL1). Lanes 1–4, livers that were injected with pVB8ii+pVI; lane 5, liver that was injected with pVB8ii only; lane 6, liver that was injected with pVB8ii+pVmI. PCR band of 300 bp indicates plasmid integration at the mpsL1 pseudo att site. MW, DNA molecular weight marker;+, positive control from an animal known to have integration at mpsL1; Saline, liver injected with saline only.

Discussion

A gene-therapy approach for hemophilia A holds considerable promise, because only modest levels of hFVIII are needed to provide a therapeutic benefit to patients. In the present study, we generated an FVIII knockout mouse tolerant to hFVIII and tested the efficacy of φC31 integrase to mediate sustained and therapeutically relevant levels of hFVIII expression. This mouse model allowed us to evaluate, for the first time, long-term hFVIII expression in a mouse model of hemophilia A without the need for immunosuppression or complex tolerance regimes.

In our initial experiments, we injected mice with the hFVIII expression plasmid pVB8 and one of three different integrase plasmids. pVI expressed wild-type φC31 integrase, whereas pVmI encoded an inactive, negative control integrase. pVhP2 expressed a mutant integrase with higher activity, but possessing a 33-amino acid amino-terminal extension, as well as several amino acid substitutions (Keravala et al., 2009). When pVB8 was injected along with pVhP2, a rapid decline in hFVIII activity was observed (Fig. 3). The kinetics of this decline in hFVIII activity correlated well with that of a host immune response, possibly due to novel features of the P2 integrase sequence or structure that were immunogenic in this strain background. Due to this observation, further use of pVhP2 was discontinued. Injection of pVB8 alone or with pVI or pVmI resulted in similar hFVIII expression kinetics (Fig. 3). These data suggested that pVB8 by itself provided low, sustained levels of hFVIII expression and that a single dose of integrase provided no large benefit during this time frame (Table 1).

In an attempt to increase the amount of circulating hFVIII, as well as to test the consequence of administering an additional dose of φC31 integrase, a second dose of pVB8+pVI was administered by hydrodynamic injection. It was possible that a second injection of pVI would result in lower hFVIII activity as a result of immunological mechanisms, because the animals had previously been exposed to the enzyme. However, the second injection of pVB8+pVI resulted in significantly higher and sustained hFVIII expression, as compared with a single injection (Fig. 4). Circulating hFVIII activity levels stabilized at ∼20% of normal, well within the therapeutic range for hemophilia A. Therefore, readministration of pVI had a beneficial effect on the levels of hFVIII activity.

To achieve higher expression levels, a redesigned hFVIII expression plasmid was constructed. A previous report demonstrated that introduction of an intron into the hFVIII cDNA resulted in increased hFVIII expression in stably transfected cells (Plantier et al., 2001). We constructed an hFVIII expression plasmid, pVB8ii, with a truncated version of the human factor IX intron-1 placed at the native intron-1 location within the hFVIII cDNA (Fig. 2). When injected, pVB8ii gave high day 2 hFVIII activities (250–330% of normal) across all groups tested. hFVIII activities this high would not be desirable clinically, due to the elevated risk of venous thrombosis and development of inhibitory antibodies. However, such levels would not be expected clinically, due the poor efficiency of hydrodynamic liver injection in large animals to date, compared with the levels seen in mice (Fabre et al., 2008). Other nonviral liver delivery methods are similarly inefficient in large animals, so the problem of excessive hFVIII levels is not one that needs to be addressed at this time. The wide therapeutic window for hFVIII levels is also helpful in this regard.

When pVB8ii was injected along with pVI, hFVIII activity stabilized by day 14 at ∼100% of normal and was maintained at this level through day 140 (Fig. 5A). When injected alone or with an inactive integrase, the initially high hFVIII activities fell rapidly and stabilized between 25% and 50% of normal through day 140. These data showed that although injection of pVB8ii plasmid alone provided therapeutic levels of hFVIII in this time frame, genomic integration of pVB8ii resulted in statistically higher levels of hFVIII expression. Extended expression of FVIII from unintegrated plasmid DNA has been reported previously (Ye et al., 2004).

Liver cells are known to be quite stable, turning over at a relatively slow rate. To induce cell cycling and to model long-term liver-cell turnover, a single injection of carbon tetrachloride was administered to the mice. Carbon tetrachloride has been shown to cause liver necrosis (Weber et al., 2003), leading to liver regeneration and loss of episomal DNA. As can be seen in Fig. 5A, hFVIII activity levels dropped after carbon tetrachloride administration in all groups. However, in the pVB8ii+pVI group, hFVIII expression was maintained, whereas in all other groups no hFVIII activity could be detected. A similar expression profile was shown by ELISA (Fig. 5B). These data suggested that for hFVIII expression over the longer term, integration may be required.

To determine if the circulating levels of hFVIII present in treated mice were sufficient to provide protection from a bleeding challenge, a tail-clip assay was performed. Mice treated with pVB8ii+pVI displayed reduced bleeding times when compared with the saline-injected control mice (Fig. 5C). Mice that received no functional integrase, and therefore had only unintegrated pVB8ii, displayed bleeding times similar to those of the saline-injected control mice (Fig. 5C). This result was not unexpected, because none of these mice had detectable hFVIII activity (Fig. 5A). Although the bleeding times of pVB8ii+pVI–treated mice were longer than those of the control C57BL/6 mice, they were significantly shorter than when no active φC31 integrase was present.

The FVIII knockout mouse is known to develop high-titer inhibitory antibodies to hFVIII rapidly and vigorously when plasmid DNA is delivered by hydrodynamic injection (Ye et al., 2004). Bethesda units of over 100 have been reported at day 40 post plasmid injection (Ye et al., 2004). To determine if our mouse model of hemophilia A developed inhibitor antibodies to hFVIII, we conducted a Bethesda assay. As shown in Fig. 6, we were unable to detect inhibitory antibodies to hFVIII. This result was expected, because a previous report had shown this mouse to be tolerant to hFVIII (Bril et al., 2006). This result was also consistent with the long-term presence of active hFVIII that was observed in many of the plasma samples from treated mice.

When PCR was conducted on liver sections from the mice at the conclusion of the study, integration of pVB8ii at the known genomic integration hotspot mpsL1 was detected (Fig. 7). Integration at other sites was not determined, as we wished only to demonstrate that genomic integration had occurred. However, it would be beneficial to the field to examine the integration specificity of φC31 integrase more completely by using contemporary deep-sequencing technologies. These data, taken along with the presence of circulating hFVIII protein and activity, suggested that mice treated with pVB8ii+pVI had genomically integrated pVB8ii and were actively expressing hFVIII. φC31 integrase has been shown to integrate plasmids more than 85% of the time as single or double integrants per cell (Sivalingam et al., 2010). Therefore, expression of hFVIII from one or two integrated plasmids per cell resulted in expression levels that provided a therapeutic effect. Future studies seeking to increase hFVIII expression further could include administration of a second dose of pVB8ii+pVI, and possibly the introduction of a second intron into the pVB8ii plasmid. Translation of these results to the clinic currently awaits the development of efficient delivery methods for plasmid DNA to the liver that are applicable to large mammals.

Acknowledgments

We thank W.E. Jung for help with mouse crosses and genomic DNA analysis and Gabriel L. Ramos for assistance with the preparation of mouse liver DNA. C.L.C. was supported in part by a Dean's Fellowship from the Stanford University School of Medicine. This work was supported by NIH grant HL068112 to M.P.C.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.P.C is an inventor on Stanford-owned patents covering phiC31 integrase. The other coauthors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Bi L. Lawler A.M. Antonarakis S.E., et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse factor VIII gene produces a model of haemophilia A. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:119–121. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brettler D.B. Kraus E.M. Levine P.H. Clinical Aspects of and Therapy for Hemophilia A. Churchill Livingstone; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 1648–1663. [Google Scholar]

- Bril W.S. MacLean P.E. Kaijen P.H., et al. HLA class II genotype and factor VIII inhibitors in mild hemophilia A patients with Arg593 to Cys mutation. Haemophilia. 2004;5:509–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bril W.S. van Helden P.M. Hausl C., et al. Tolerance to factor VIII in a transgenic mouse expressing human factor VIII cDNA carrying an Arg(593) to Cys substitution. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;95:341–347. doi: 10.1160/TH05-08-0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalberg T.C. Portlock J.L. Olivares E.C., et al. Integration specificity of phage phiC31 integrase in the human genome. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:28–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi T. Huang M. Gorman C. Jaenisch R. A generic intron increases gene expression in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:3070–3074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuah M.K. VandenDriessche T. Clinical gene transfer studies for hemophilia A. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2004;30:249–256. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D.N. Tuddenham E.G. Molecular genetics of familial venous thrombosis. Br. Med. Bull. 1994;50:833–850. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre J.W. Grehan A. Whitehorne M., et al. Hydrodynamic gene delivery to the pig liver via an isolated segment of the inferior vena cava. Gene Ther. 2008;15:452–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrovsky V. Calos M.P. Factoring nonviral gene therapy into a cure for hemophilia A. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2008;10:464–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth A.C. Olivares E.C. Thyagarajan B. Calos M.P. A phage integrase directs efficient site-specific integration in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5995–6000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090527097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui T. Reheman A. Ni H., et al. Abnormal hemostasis in a knock-in mouse carrying a variant of factor IX with impaired binding to collagen type IV. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;7:1843–1851. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held P.K. Olivares E.C. Aguilar C.P., et al. In vivo correction of murine hereditary tyrosinemia type I by φC31 integrase-mediated gene delivery. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer L.W. Scandella D. Factor VIII inhibitors: structure and function in autoantibody and hemophilia A patients. Semin. Hematol. 1994;31:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin D. Zhang T. Gui T., et al. Creation of a mouse expressing defective human factor IX. Blood. 2004;104:1733–1739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemball-Cook G. Tuddenham E.G.D. Wacey A.I. The factor VIII structure and mutation resource site: HAMSTeRS version 4. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:216–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keravala A. Lee S. Thyagarajan B., et al. Mutational derivatives of phiC31 integrase with enhanced efficiency and specificity. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:112–120. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhstoss S. Rao R.N. Analysis of the integration function of the Streptomycete bacteriophage FC31. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;222:897–908. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90584-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird P.W. Zijderveld A. Linders K., et al. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesner R. Zhang W. Noske N. Ehrhardt A. Critical amino acid residues within the phiC31 integrase DNA-binding domain affect recombination activities in mammalian cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010;21:1104–1118. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mátrai J. Chuah M.K. VandenDriessche T. Preclinical and clinical progress in hemophilia gene therapy. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2010;17:387–392. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833cd4bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao C.H. Ohashi K. Patijn G.A., et al. Inclusion of the hepatic locus control region, an intron, and untranslated region increases and stabilizes hepatic factor IX gene expression in vivo but not in vitro. Mol. Ther. 2000;1:522–532. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares E.C. Hollis R.P. Chalberg T.W., et al. Site-specific genomic integration produces therapeutic factor IX levels in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nbt753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrus I. Chuah M. VandenDriessche T. Gene therapy strategies for hemophilia: benefits versus risks. J. Gene Med. 2010;12:797–809. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantier J.L. Rodriguez M.H. Enjolras N., et al. A factor VIII minigene comprising the truncated intron I of factor IX highly improves the in vitro production of factor VIII. Thromb. Haemost. 2001;86:596–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J.S. Ragni M.V. White G.C., 2nd, et al. Phase 1 trial of FVIII gene transfer for severe hemophilia A using a retroviral construct administered by peripheral intravenous infusion. Blood. 2003;102:2038–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J. Collins M. Sharp A.H. Hoyer L.W. Prevention and treatment of factor VIII inhibitors in murine hemophilia A. Blood. 2000;95:1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch H. Lehmann M. Structural analysis of the actinophage FC31 attachment site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5187–5189. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth D.A. Tawa N.E., Jr. O'Brien J.M., et al. Nonviral transfer of the gene encoding coagulation factor VIII in patients with severe hemophilia A. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1735–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivalingam J. Krishnan S. Ng W.H., et al. Biosafety assessment of site-directed transgene integration in human umbilical cord-lining cells. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1346–1356. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe H.M. Smith M.C.M. In vitro site-specific integration of bacteriophage DNA catalyzed by a recombinase of the resolvase/invertase family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:5505–5510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan B. Olivares E.C. Hollis R.P., et al. Site-specific genomic integration in mammalian cells mediated by phage φC31 integrase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:3926–3934. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3926-3934.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillett D. Neilan B.A. Enzyme-free cloning: a rapid method to clone PCR products independent of vector restriction enzyme sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e26. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber L.W. Boll M. Stampfl A. Hepatotoxicity and mechanism of action of haloalkanes: carbon tetrachloride as a toxicological model. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2003;33:105–136. doi: 10.1080/713611034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. Reding M. Qian J., et al. Mechanism of the immune response to human factor VIII in murine hemophilia A. Thromb. Haemost. 2001;85:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye P. Thompson A.R. Sarkar R., et al. Naked DNA transfer of factor VIII induced transgene-specific, species-independent immune response in hemophilia A mice. Mol. Ther. 2004;10:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]