Abstract

The cohesin complex, named for its key role in sister chromatid cohesion, also plays critical roles in DNA repair and gene regulation. It performs all three functions in single cell eukaryotes such as yeasts, and in higher organisms such as man. Minor disruption of cohesin function has significant consequences for human development, even in the absence of measurable effects on chromatid cohesion or chromosome segregation. Here we survey the roles of cohesin in DNA repair and gene regulation, and how these functions vary from yeast to man.

Introduction

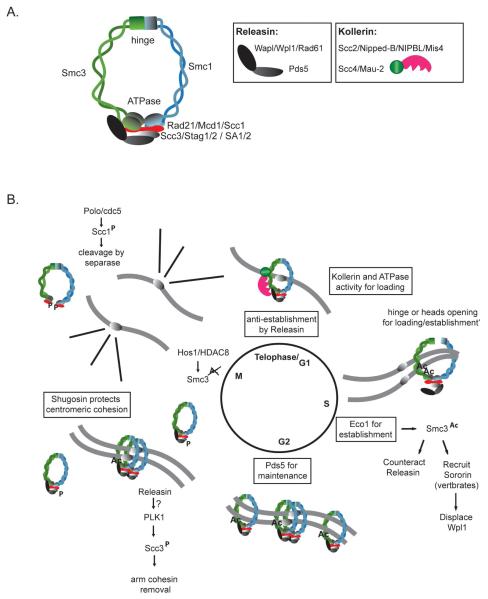

Cohesin is a member of a group of protein complexes that contain Structural Maintenance of Chromosome (SMC) proteins. Prokaryotes usually have one SMC complex that performs multiple roles in chromosome mechanics, while eukaryotes have multiple specialized complexes, including cohesin. Cohesin, which consists of a heterodimer of Smc1 and Smc3, the Rad21 (Mcd1/Scc1) kleisin protein, and Stromalin (SA, Scc3, Stag1/2) (Figure 1) has critical roles in sister chromatid cohesion, DNA repair, and gene regulation [1].

Figure 1. Cohesin structure and cell cycle regulation.

(A) A schematic representation of the cohesin complex and its subunits. (B) An overview of cohesin chromatin loading, and removal from chromosomes, as well as cohesion establishment during an unperturbed cell cycle. Main steps during the cohesion cycle and species differences are highlighted, for further details see the main text, Phosphorylation (P), Acetylation (Ac).

SMC proteins fold back on themselves in the “hinge” region to form antiparallel coiled-coil arms, with the N and C termini coming together in “head” domains that contain ABC-type ATPases (Figure 1). Cohesin forms a ring-like structure, with Rad21 bridging the SMC head domains. The internal cohesin diameter is on the order of 35 by 50 nm, large enough to encircle two DNA molecules. Thus, the leading idea is that cohesin binds to chromosomes topologically, and that it mediates sister chromatid cohesion by one ring encircling both sisters, or by two rings, each encircling one sister, interacting with each other [1]. The experimental evidence that cohesin topologically entraps circular yeast minichromosomes is compelling, but the mechanism of cohesion remains unresolved [2,3].

Cohesin binding and chromosome localization differ between organisms

Figure 1 outlines the cohesin chromosome binding cycle, reviewed in detail elsewhere [4]. Cohesin is loaded onto chromosomes in telophase in higher eukaryotes, but at the G1/S boundary in S. cerevisiae. Cohesin is loaded by a protein complex, recently dubbed kollerin [4], consisting of an adherin protein (Scc2, Mis4, Nipped-B, NIPBL) and the Scc4 (Mau-2) protein. Kollerin binds chromosomes and is required, along with ATP hydrolysis by the SMC proteins, for topological binding of cohesin [4-6]. The mechanism of cohesin loading is unknown, but evidence suggests that the ring may open at the Smc1/3 hinge dimer interface to permit DNA entry [4]. The Smc1/3 hinge dimer binds DNA, which may position it for loading [7].

Sister chromatid cohesion is established during S phase, in coordination with DNA replication, but the mechanisms are unknown [1,4,8]. Cohesion establishment requires specialized DNA replication factors and acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 (Ctf7) in budding yeast. Two Eco1 orthologs in Drosophila (Deco, Sans) and mammals (Esco1, Esco2) also regulate cohesion. Smc3 acetylation counteracts an anti-cohesion establishment function of the releasin complex, formed by the Pds5 and Wapl (Wpl1, Rad61) proteins. Pds5 is also paradoxically required to establish and/or maintain cohesion. In vertebrates and Drosophila, acetylation of Smc3 recruits the Sororin (Dalmatian) protein, which protects cohesin from removal by displacing Wapl from the releasin complex [9]. Hos1 in yeast, and HDAC8 in human cells deacetylates Smc3 in preparation for the next cell cycle [4,10-12].

The process of cohesin removal for cell division differs between yeast and higher eukaryotes [1,4]. In yeast, Polo/cdc5 phosphorylates the Scc1 cohesin subunit, making it sensitive to proteolysis by separase upon its activation at the metaphase to anaphase transition. In higher eukaryotes cohesin removal is a two-step process, where phosphorylation of the SA/Scc3 subunit (Stag1/2) by a Polo-like kinase stimulates cohesin removal from the chromosome arms in prophase, possibly driven by releasin. Shugoshin protein blocks removal of pericentric cohesin until activation of separase at the metaphase to anaphase transition [13].

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) reveals that cohesin chromosome binding dynamics are complex during interphase, when gene regulation and DNA repair occur. There are multiple binding modes with chromosomal residence times ranging from seconds to hours [5,14,15]. Cohesin with a residence time of several seconds likely binds DNA directly without topologically entrapping it [7], while stable cohesin with a residence time of several minutes to hours is likely bound topologically. The residence time of stable cohesin is greater in G2 than in G1, indicating that it is further stabilized when mediating sister cohesion. In Drosophila, the amount of stable topological cohesin during interphase depends on the dosage of Nipped-B, Pds5 and Wapl, indicating that it is determined by a continuous balance between loading by kollerin and removal by releasin [5]. A fraction of both Nipped-B and Pds5 have the same unusually long residence time as topological cohesin, suggesting that kollerin and releasin can interact tightly with cohesin [5].

Cohesin binding is high around centromeres in all organisms, but there are intriguing differences in binding along chromosome arms. In S. cerevisiae, cohesin binding sites only partially overlap those for the Scc2 adherin, and most arm binding sites are located between convergently transcribed genes, giving rise to the ideas that cohesin slides from loading sites to the binding sites, and that it might be pushed there by RNA polymerase [16,17]. In the fission yeast S. pombe, cohesin co-localizes with the Mis4 adherin at highly expressed genes, and localizes between some, but not all convergent genes in G2 [18,19].

Drosophila shows a very different pattern. Cohesin and the Nipped-B adherin co-localize almost completely genome-wide, with the exception of meiotic centromeres, which bind cohesin, but not Nipped-B [20,21]. In addition to DNA replication origins, Nipped-B and cohesin bind preferentially to a subset of active genes, with the highest levels at the transcription start sites, and are excluded from inactive or silenced genes [21-23].

Mammalian cells show a cohesin-binding pattern similar to that in Drosophila, except that cohesin, but not the NIPBL adherin, bind closely adjacent to a large fraction of the sites that bind the CTCF transcription factor [24-30]. CTCF interacts directly with the cohesin SA (Stag2) subunit, and thus may recruit cohesin directly, or trap cohesin that slides along the chromosome from loading sites [28,31]. This is potentially an important distinction, because if cohesin is recruited directly in the absence of adherin it is unlikely to encircle DNA. Drosophila CTCF lacks the domain that interacts with cohesin, and does not co-localize with cohesin.

Different cohesin functions require different amounts of cohesin

In S. cerevisiae, as little as 13% of normal cohesin levels supports sister chromatid cohesion, but there are defects in DNA repair and chromosome condensation [32]. Reduction of cohesin levels by 80% in Drosophila cells has dramatic effects on gene transcript levels, but no significant effect on cohesion or chromosome segregation [33].

Even more strikingly, heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the human NIPBL adherin gene, which reduce expression by 30% or less, cause Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS), with severe effects on physical and mental development [34,35]. Individuals with CdLS grow slowly, and suffer cognitive deficits, autism and abnormalities in organs and limbs. Cells from CdLS patients show changes in gene expression and mild effects on DNA repair, without overt effects on sister cohesion [25,36,37]. Milder forms of CdLS are caused by dominant missense mutations in mitotic Smc1 (SMC1A), also with changes in gene expression, mild defects in DNA repair, but no cohesion defects [25,38-40]. Minor deficits in the expression of Drosophila Nipped-B, Smc1, or pds5, zebrafish rad21, and mouse Nipbl, Pds5A or Pds5B also have significant effects on gene expression and development without effects on cohesion or chromosome segregation [41-47]. Gene expression changes occur upon depletion of cohesin in non-dividing cells, confirming that cohesin affects gene expression independently of its roles in cell division [48-50]. Cohesin can directly modulate transcription, given that the genes that change in expression upon cohesin depletion or mutation are highly enriched for cohesin-binding genes, and that effects on cohesin-binding genes can occur within a few hours of cohesin depletion [23-25,33].

Thus, gene expression and development are most sensitive to cohesin activity, followed by DNA repair, and then sister chromatid cohesion. It may be that cohesion is the most ancient and inflexible role of cohesin, and thus the most stable. As outlined below, current evidence reveals that cohesin regulates transcription by multiple organism- and context-dependent mechanisms, and plays multiple roles in DNA repair and genome stability.

Cohesin, heterochromatin and gene silencing

Cohesin binds heterochromatin in centromeric and telomeric regions, and functionally interacts with proteins that bind these regions in organisms from yeast to man. In S. cerevisiae, cohesin also binds the silent mating type loci, and cohesin mutations allow SIR silencing proteins to spread beyond the normal boundary that flanks the HMR silent mating type locus [51]. The HMR boundary forms at a tRNA gene promoter, which is required together with a nonenzymatic portion of the SIR2 histone deacetylase for sister cohesion at this site, in part because the TFIIIC transcription factor recruits kollerin [52-56]. Even with topologically bound cohesin at HMR, SIR2, but not silencing, is required for cohesion, suggesting that SIR2 directly participates in cohesion [53,56].

Despite this intimate relationship between cohesin and SIR2, cohesin does not contribute to silencing. In contrast to sir2 mutations, inactivation of cohesin in G1, and adherin mutations do not derepress silenced genes [57,58]. An adherin missense mutation, however, affects expression of the GAL2 gene that is positioned closely to the nucleolar rDNA repeats, some of which are silenced, and expression of a HIS3 reporter gene positioned near the tRNA gene clusters that form adjacent to the nucleolus (Figure 2) [57]. In this adherin mutant, GAL2 is easier to induce, and HIS3, which is repressed by tDNA clustering, increases in expression. Altered nucleolar morphology and reduced tDNA clustering accompany these expression changes. Also, many of the genes dysregulated by cohesin inactivation in G1 are situated adjacent to each other [58]. These findings argue that many of the effects of cohesin on gene expression in S. cerevisiae stem from repositioning of genes to new locations in the nucleus.

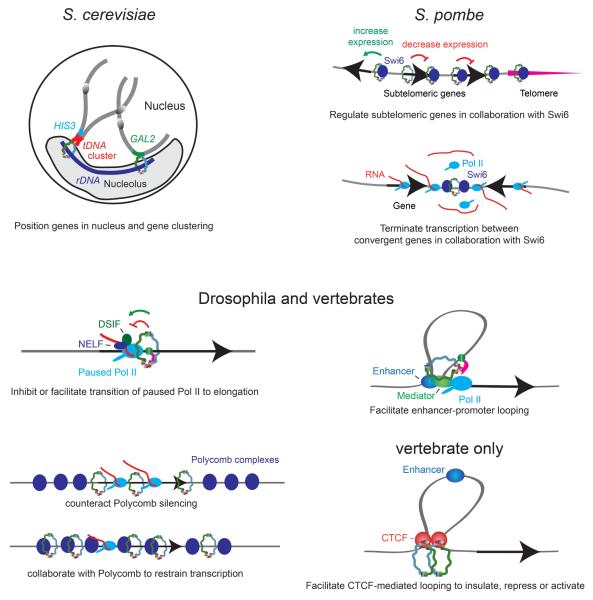

Figure 2. Roles of cohesin in gene expression.

In S. cerevisiae cohesin regulates genes by controlling their positioning within the nucleus, including proximity to the nucleolus and tDNA clusters. In S. pombe cohesin interacts with the Swi6 heterochromatin protein and together they regulate subtelomeric genes and increase transcriptional termination between convergent genes. In Drosophila, and likely vertebrates, cohesin and adherin selectively bind genes with promoter-proximal paused RNA polymerase (Pol II) that also bind the DSIF and NELF pausing complexes. In a context and gene-specific manner, cohesin and adherin modulate transition of Pol II to elongation by unknown mechanisms. Adherin and cohesin facilitate enhancer-promoter looping, and can counteract silencing by Polycomb Group proteins, and more rarely, cooperate with Polycomb proteins to restrain, but not silence genes. In vertebrates, cohesin has likely substituted for other CTCF cofactors seen in Drosophila, and directly interacts with CTCF to facilitate looping between CTCF binding sites, which can contribute to transcription repression, activation and insulation.

In S. pombe, cohesin interacts with the Swi6 heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) homolog, which is required for cohesin to bind to the pericentric domains [59,60]. Adherin and cohesin mutations alter expression of few genes in fission yeast arrested in G1, but remarkably, these are clustered in subtelomeric domains near the Swi6-bound telomeres (Figure 2) [61]. Cohesin is required for Swi6 binding to the telomere and subtelomeric region, and cohesin and swi6 mutations have similar effects on gene expression. The genes closest to the telomere increase in expression, while the more distal genes decrease. It remains to be determined if these effects correlate with changes in telomeric clustering or positioning, akin to the effects of cohesin on gene expression in S. cerevisiae.

Cohesin and Swi6 also affect transcription during G2 in S. pombe. Double-stranded RNA created by transcription through the 3′ ends of convergent genes leads to formation of Swi6 and cohesin binding regions between convergent genes through RNAi-dependent mechanisms, and subsequent transcriptional termination in these regions (Figure 2) [18]. Cohesin mutations reduce termination, indicating that cohesin contributes to termination in an unknown manner.

There is less evidence that cohesin regulates genes through heterochromatin-related mechanisms in higher eukaryotes. In human facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD), a reduction in the number of repeats of a 3.3 kb sequence (D4Z4) in a subtelomeric region of chromosome 4 leads to reduced histone H3K9 methylation, a heterochromatic modification, and reduced HP1γ and cohesin binding to the repeats, but whether or not this cohesin loss alters gene expression is unknown [62]. Mammalian heterochromatin proteins do not appear to be required for cohesin binding to pericentric regions, although it has been reported that mammalian NIPBL interacts with HP1 proteins, and that HP1γ depletion reduces recruitment of NIPBL to DNA breaks [63-65]. Adherin and cohesin do not co-localize with HP1 at any of the prominent HP1-binding regions along chromosome arms in Drosophila, indicating that HP1 does not recruit them [20,21]. Thus, although cohesin concentrates in heterochromatic regions in higher organisms as in fungi, it may have less direct functional interactions with heterochromatin proteins.

Cohesin does show functional interactions with the Polycomb group (PcG) epigenetic silencing proteins in Drosophila. Drosophila cohesin paradoxically interacts with the PRC1 PcG complex in nuclear extracts, but is largely excluded from PcG-silenced regions on chromosomes, as detected by the histone H3 lysine 27 trimethyl (H3K27me3) mark made by the PRC2 complex (Figure 2) [21,66]. This exclusion is consistent with the isolation of verthandi Rad21 cohesin subunit mutations in a screen for genes that counteract PcG silencing [67,68]. Importantly, however, there are rare instances in which extended PcG-targeted domains are also coated with cohesin (Figure 2) [33]. These regions invariably contain genes encoding transcription factors that regulate development, such as engrailed. They are not silenced, but increase dramatically in expression upon depletion of adherin, cohesin, or PcG proteins. Thus, in contrast to regions targeted only by PcG proteins, these domains require both cohesin and PcG complexes to maintain a lower, restrained level of gene expression. Genome-wide analysis reveals that these genes are among the most sensitive to cohesin dosage.

The rare cohesin-PcG co-targeted genes in Drosophila are similar to bivalent genes in mammalian embryonic stem (ES) cells, which have both the PRC2 H3K27me3 modification, and the H3K4me3 mark associated with active promoters. Some 70% of the genes in mouse ES cells that increase the most in expression with cohesin depletion are bivalent [24,69]. Like the cohesin-PcG genes in Drosophila, bivalent genes largely encode transcription factors and other proteins that control development. Because cohesin is required to maintain the multipotent state of ES cells, it remains to be determined how many of the increases in bivalent gene expression upon cohesin depletion reflect direct repression of these genes by cohesin in combination with PcG proteins, as opposed to increases caused by differentiation. Nonetheless, these findings argue that cohesin and PcG silencing proteins play interlinked roles in development and differentiation, opposing each other in many cases, and cooperating in others.

Cohesin selectively binds and regulates genes with paused RNA polymerase

Clues to how cohesin and PcG proteins regulate genes in Drosophila arise from the findings that both preferentially bind genes in which RNA polymerase pauses after transcribing several nucleotides (Figure 2) [70,71]. The DSIF (DRB sensitivity inducing factor) and NELF (negative elongation factor) complexes associate with paused RNA polymerase II (Pol II), and release of Pol II from the paused state controls gene expression during development [72]. It remains to be seen if cohesin also selectively binds genes with paused RNA polymerase in vertebrates, but it binds a pausing site in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) [73].

Many of the genes with paused polymerase decrease in expression and many increase in expression upon cohesin depletion, indicating that the effect of cohesin is context-dependent. Some of the genes that increase the most in expression upon cohesin depletion are the rare cohesin-PcG co-targeted genes, suggesting that repressor proteins may be one factor that determines whether cohesin activates or represses transcription.

Cohesin is not required for pausing, although it binds close to paused polymerase [71]. Its effects on expression also differ from those of the DSIF and NELF pausing factors. At strongly repressed genes, including some co-targeted by PcG proteins, cohesin and pausing factors co-depletion experiments indicate that cohesin interferes with the transition of paused polymerase to elongation at a step different from those controlled by the pausing factors. Cohesin is unlikely to simply obstruct polymerase movement, considering that it increases expression of many genes that it binds, and that cohesin depletion does not increase the rate of transcriptional elongation along the ecdysone receptor (EcR) gene, which binds cohesin over much of the 80 kb transcription unit [71].

Pausing release requires phosphorylation of NELF, DSIF and the Pol II C terminal domain by the Ckd9 subunit of P-TEFb, which is recruited by transcriptional activators [74,75]. With the current evidence, therefore, some likely scenarios are that cohesin represses by interfering with modification of the transcriptional machinery, pausing factor release, or binding of elongation factors. Indeed, a notable feature of cohesin-binding genes is that they lack the H3K36me3 mark made by the Set2 protein that binds elongating polymerase [71,76]. In genes activated by cohesin, such as the myc gene in Drosophila and vertebrates [77], cohesin could facilitate transition to elongation through related mechanisms.

Cohesin facilitates enhancer-promoter looping and transcriptional activation

One mechanism by which cohesin can facilitate transition of paused polymerase to elongation is by increasing enhancer-promoter communication (Figure 2). Drosophila Nipped-B facilitates activation of the cut and Ultrabithorax homeobox genes by enhancers located some 80 and 50 kbp from their promoters [44]. Chromosome conformation capture (3C) experiments show that adherin and cohesin also facilitate enhancer promoter contact and activation of pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic stem cells, β-globin genes in mouse and human erythroleukemia cells and fetal mouse liver, and the Tcra T cell receptor gene in mouse thymocytes [24,49,78]. Adherin and cohesin associate with the enhancers and promoters, and reducing their dosage decreases looping and gene expression. Importantly, cohesin binding and enhancer-promoter looping are specific to cells in which the genes are active. The mechanisms by which cohesin facilitates enhancer-promoter contacts are unknown, although one obvious idea is that cohesin holds them near to each other in the same way it holds sister chromatids together (Figure 2).

In mouse ES cells, cohesin interacts with the Mediator complex and co-localizes with it at enhancers and promoters (Figure 2) [24]. Mediator binds RNA polymerase and regulates many aspects of transcriptional activation and repression, including enhancer-promoter looping, activator function, Pol II phosphorylation and elongation [79,80]. Thus the cohesin-Mediator interaction may be involved in cohesin’s control of the transition of paused polymerase to elongation and enhancer-promoter looping. Indeed, it raises the possibility that cohesin can regulate a gene by multiple mechanisms at the same time, and even have simultaneous positive and negative effects. Coinciding opposing effects might explain why reducing adherin dosage has an effect opposite to reducing cohesin dosage on expression of the cut gene in the developing Drosophila wing margin, or why small reductions in cohesin dosage decrease expression of Enhancer of split genes, and larger reductions increase their expression [33,45].

Consistent with the idea that cohesin regulates transcriptional activation and enhancer-promoter looping is the burgeoning evidence that cohesin associates with diverse cell type-specific transcription factor binding sites. Upon stimulation of breast cancer cells by estrogen, cohesin co-localizes with many estrogen receptor binding sites, and cohesin depletion alters the cellular response to estrogen [81]. Cohesin associates with liver-specific transcription factor binding sites in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells [81]. Not only does cohesin maintain mouse ES cell pluripotency by facilitating enhancer-promoter looping and activation of pluripotency genes such as Nanog and Oct4, it also associates with many Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 protein binding sites [24,26]. Nanog interacts with cohesin and the Wapl releasin subunit, suggesting that direct recruitment by activators is one mechanism by which cohesin selectively binds to specific genes. Upon differentiation of mouse ES cells, cohesin shifts to CTCF sites and sites bound by differentiation-specific transcription factors [26].

Cohesin and CTCF

CTCF is a zinc finger DNA-binding protein that functions in transcriptional repression, activation, and as an insulator that interferes with enhancer-promoter interactions [82]. Cohesin and CTCF interact, co-localize, and function together to regulate transcription [24-27]. Loops form between many sites that bind CTCF, and cohesin depletion reduces looping, with correlating effects on gene expression (Figure 2) [83-89]. For instance, cohesin depletion diminishes insulation by the H19-Igf2, chicken β-globin locus, and MHC II C1 CTCF insulators [27,30,90].

A recent study using mouse embryonic fibroblasts, which strongly express H19 and Igf2, found that cohesin or CTCF depletion did not reduce insulation at the imprinted maternal locus, but increased Igf2 expression from the paternal locus, suggesting that CTCF and cohesin act as repressors [91]. CTCF and cohesin depletion also did not reduce imprinting at other loci, but increased transcript levels in some cases. Because increased expression of Igf2 also occurred in the absence of the CTCF binding sites on the maternal allele, it remains unclear if the repressive effects of CTCF and cohesin are direct.

The unexpected non-allelic effects of CTCF and cohesin on Igf2 expression might reflect a role for CTCF and cohesin in overall chromatin organization, as proposed for the human β-globin locus, where 3C analysis showed reduced cell type-specific looping between several CTCF binding sites, and reduced expression of the fetal γ-globin gene upon cohesin and CTCF depletion [85].

Cohesin’s role in CTCF function is specific to vertebrates. Drosophila CTCF recognizes the same DNA sequence and insulates, but does not require cohesin, relying instead on other factors such as the CP190 zinc finger/BTB co-insulator protein [92-94]. The CTCF accessory factors in Drosophila presumably do not bind DNA topologically, and thus CTCF function in vertebrate cells might not require topologically bound cohesin.

Evolution of cohesin’s roles in gene expression and development

Cohesin has acquired additional roles in gene regulation as organism complexity increased (Figure 2). It is not surprising, therefore, that given the developmentally important genes it controls, and the number of ways it exerts these influences, that even modest disruption of cohesin function alters many aspects of human development. What remains unclear is how much each of these activities are mechanistically related to each other, and reflect cohesin’s ability to hold two DNA molecules together, or if new specific functional interactions with basal transcriptional machinery, activator and insulator proteins have arisen during evolution.

DNA repair is an ancient cohesin function

Two different strategies are used to repair a DNA double strand break (DSB) depending on cell type and phase of the cell cycle. Non Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), used primarily in G1 phase, results in re-ligation of the broken DNA, and frequently leads to loss of genetic information, while homologous recombination (HR) depends on a homologous DNA template, and thus is preferentially performed during the S and G2 phases, using a sister chromatid template [95]. Because sister chromatids are identical, HR leaves genetic information intact [96]. The finding that DNA repair efficiency increases when yeast cells go from G1 to G2, argues that completion of replication, i.e. formation of sister chromatids, is important for repair [97]. In addition, HR requires close proximity between the broken DNA and the repair template, therefore the importance of sister chromatid cohesion for repair was predicted [98].

The DSB repair function of cohesin is ancient, inherited from its bacterial SMC protein ancestors [99]. An early indication of cohesin’s role in DNA repair in eukaryotes, predating the discovery of its role in sister chromatid cohesion, was that a mutated Rad21 cohesin subunit rendered S. pombe cells sensitive to γ-irradiation and defective in DSB repair [100]. In addition a mammalian SMC1/3 containing complex was demonstrated in biochemical experiments to facilitate certain types of DNA repair [101]. Studies in Rad21-depleted chicken DT40 cells, cell lines from breast cancer patients with impaired Rad21 function, and depletion of Rad21 in HeLa cells confirmed that cohesin is also important for repair in higher eukaryotes [102-104].

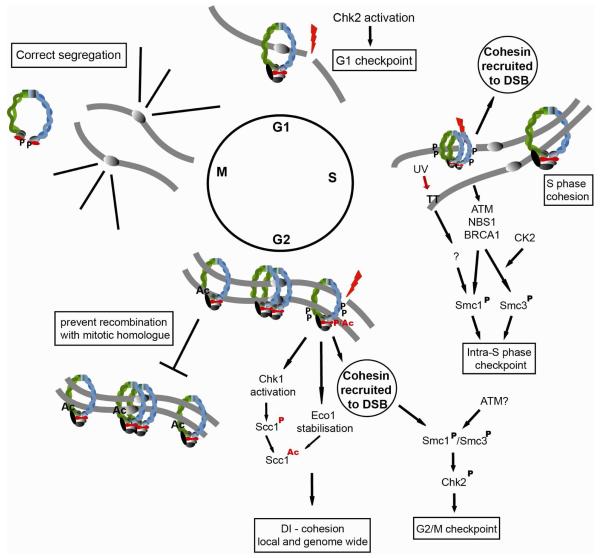

Cohesin and checkpoint activation

Cell cycle checkpoint activation is the initial response to DNA damage, delaying cell cycle progression until genome integrity is restored [105]. Early evidence that cohesin is important for checkpoint activation came from human cell and mouse studies, when it was discovered that ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) and NBS1 (Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome protein 1)-dependent phosphorylation of Smc1 and Smc3 is important for induction of the intra S phase checkpoint in response to irradiation (Figure 3) [106-109]. It was later found that cohesin is also involved in the damage-induced checkpoint in post-replicative human cells. The effector function of Smc1/3 phosphorylation for DNA damage is still unclear, however depletion of Smc3 or Scc1 allows cells to proceed through the cell cycle after DSB induction, leading to a majority of cells with broken chromosomes [110].

Figure 3. Functions for Cohesin in DNA damage responses, DNA repair and genome integrity.

The different DNA damage response and repair actions that cohesin has been shown to be involved in are indicated in relation to the cell cycle. For further details see the main text, Phosphorylation (P), Acetylation (Ac).

One likely reason for the failure to activate the checkpoint properly in cohesin deficient cells is inefficient activation of the Chk2 kinase. That Chk2 is not phosphorylated properly in G1 in the absence of Rad21, when there is no cohesion, suggests that cohesin, and not sister chromatid cohesion per se, is required for checkpoint activation. Supporting this idea, inactivation of Sororin, a metazoan-specific cohesion factor, prevents establishment and maintenance of cohesion, but not activation of the checkpoint [110]. In C. elegans scc-2 adherin mutants, binding of cohesin to chromosomes and DNA repair are both diminished during meiosis [111]. Despite the lack of DSB repair, the DNA damage checkpoint is still not activated, arguing that activation requires chromosome-bound cohesin. So far cohesin has not been reported to be directly involved in checkpoint signaling or maintenance in yeast.

Sister chromatin cohesion and postreplicative DSB repair

Cohesin is not known to be required for checkpoint activation in response to a DNA break in yeast, but is required for repair. Studies by Nasmyth and colleagues in S. cerevisiae showed that DSB repair in G2 is impaired if DNA replication occurs in the absence of functional cohesin, and that reintroduction of cohesin during G2 cannot rescue this deficiency [112]. It was further concluded that sister chromatid cohesion, and not just cohesin binding, was important for repair because inactivation of Eco1, which blocks cohesion, but not cohesin binding, also causes repair deficits. Depletion of Sororin diminishes both cohesion and repair but not cohesin DNA binding, indicating that cohesion is also required for postreplicative DSB repair in mammalian cells [104].

Recruitment of cohesin to DNA breaks

The first indication that cohesin is recruited to damaged DNA came from a study where human cells were exposed to high doses of laser irradiation [113]. However, nuclear structure was severely disrupted and actual break localization may not have been detected. Milder methods for inducing damage detected phosphorylation of SMC1, but not increased SMC1 levels at break sites [114]. Regardless, recruitment of cohesin to single site-specific DNA breaks has been confirmed in yeast and human cells (Figure 3) [115-117].

In S. cerevisiae, γ-radiation induced breaks are not repaired if cohesin loading, and thereby localization to breaks, is inactivated in G2 after establishment of S phase cohesion [116,117]. Thus, despite proper S phase cohesion, cohesin has to bind at breaks for repair to occur. It was further demonstrated, taking advantage of temperature-sensitive S phase cohesin and wild type cohesin expressed in G2, that DNA damage induces cohesion, termed damage induced (DI)-cohesion (Figure 3) [116,118].

Regulation of DI-cohesion

In yeast, cohesin loading at a DSB, and establishment of cohesion on both damaged and undamaged chromosomes requires both the DNA damage response pathway and several factors that regulate chromatid cohesion (Figure 3) [116,117,119,120]. Thus, DI-cohesion is not established in the absence of functional Eco1, which is also essential for cohesion establishment during S phase [119,120]. Cohesion establishment during S phase is coupled to DNA replication. Because DSB repair via HR triggers DNA synthesis, and Eco1 is required for DI-cohesion, it was predicted that DI-cohesion would also require DNA synthesis. However, deletion of Rad52, required for strand invasion during HR and thus DNA synthesis, does not reduce DI-cohesion. Even more striking, DI-cohesion is activated throughout the genome in response to a single DSB, demonstrating that cohesion can be established independently of DNA synthesis during G2 [119,120].

What signal is transmitted by a DSB to allow de novo cohesion establishment? Koshland and co-workers found that the checkpoint kinase Chk1 is required for DI-cohesion and was believed to phosphorylate a conserved serine residue (S83) of Scc1. Although such phosphorylation could not be detected in vivo, a mutant that cannot be phosphorylated at S83 was unable to establish DI-cohesion. S83 phosphorylation was suggested to augment acetylation of K84 and K210 residues in Scc1 by Eco1 [121]. During S phase, Eco1 acetylation of the Smc3 cohesin subunit counteracts the anti-establishment activity of Wpl1 [122-127]. Thus, Chk1 phosphorylation of Scc1 in response to DNA damage was suggested to help counteract Wpl1 (Rad61) to specifically establish postreplication cohesion. In addition, DNA damage during G2/M stabilizes Eco1 by preventing its phosphorylation by Clb2-Cdk1 and subsequent ubiquitin-mediated degradation, which may further increase modification of cohesin to counteract Wpl1 (Figure 3) [128].

Recent reports suggest that DI-cohesion also occurs in multicellular organisms. A single DSB increases the proximity of sister chromatids in the region close to a DNA break in chicken DT40 cells [129]. Furthermore, alignment of sister chromatids is transiently enhanced in response to X-irradiation or mitomycin C in Arabidopsis thaliana [130]. This process may also be regulated by the same checkpoint as in yeast, given that Chk1 is constitutively phosphorylated in human cells with mutant Esco2 [131].

Is local and genome-wide DI-cohesion critical for DSB repair?

A central question is to what extent DI-cohesion contributes to DNA repair. Repair is abolished if Eco1 is inactivated, which prevents DI-cohesion, but does not affect recruitment of cohesin to DNA breaks. This argues that DI-cohesion is required for repair [119,120]. Newer data, however, indicate that this may be an oversimplification. Inactivation of other factors required for full formation of DI-cohesion genome-wide, such as Tel1, Mec1, Chk1, and H2A phosphorylation leaves DSB repair mostly unperturbed [132]. Because inactivation of adherin and Eco1 abrogates both DI-cohesion and DSB repair, these proteins have other functions in repair besides establishing DI-cohesion. These roles remain to be determined, but adherin is likely required for topological binding of cohesin at a DNA break, and it can be speculated that Eco1 modification of cohesin counteracts the propensity of releasin to remove this topologically-bound cohesin.

Removal of cohesin by separase during interphase appears to be required to complete DNA break repair in S. pombe [133]. Possibly, this transient or local removal of cohesion at a break site is why cohesion is reinforced genome-wide. This might also be the case in higher eukaryotes, as a recent study in human cells revealed that cohesin binding is reinforced genome wide after irradiation [134].

Genome-wide DI-cohesion may also prevent precocious sister chromatid separation during a G2/M arrest caused by checkpoint activation. This question has been addressed with different outcomes in budding yeast. The absence of functional Eco1 during G2, using a temperature-sensitive allele of Eco1 (eco1-1) that gives a high background of precocious sister separation, did not increase chromosome missegregation, nor did a missense mutation, eco1(W216G), which mimics a human ESCO2 Roberts syndrome mutation [119,135,136]. In contrast, a 3-fold increase in loss of unbroken chromosomes was seen in the eco1ack- mutant strain after break induction, although the total frequency was very small [120].

As discussed above, cohesin also regulates gene expression, and thus one unexplored possibility is that that DI-cohesion may also be important for the characteristic transcriptional response to DNA damage [137,138].

Additional functions for cohesin in DNA repair

Cohesin’s role in DNA repair has mainly been attributed to its ability to hold sister chromatids together. This is beneficial for HR, where the preferred template for repair, the sister chromatid with identical sequence, is held in close contact with the broken DNA molecule. Indeed, a four-fold reduction of the Scc1 or Smc3 cohesin components decreases survival in response to irradiation and increases recombination between homologues, which augments the risk of loss of heterozygosity [139]. In addition to promoting repair from the sister chromatid, it has also been suggested that cohesin can regulate the choice between the HR and the NHEJ pathways for DSB repair [140]. Cohesin is also required for DSB repair during meiosis [141]. Here it is critical that the programmed DSBs created for initiation of meiotic recombination between homologous chromosomes are repaired via the homologous chromosome and not the sister chromatid [142,143]. In line with this, cohesion is relaxed in the immediate vicinity of meiotic DSBs, indicating that it is regulated differently in meiosis than in somatic cells [144].

Do DNA repair deficits contribute to the molecular etiology of the cohesinopathies?

Human developmental disorders, such as CdLS, caused by dominant mutations in adherin and cohesin subunits, and Roberts-SC phocomelia syndrome (RBS/SC) caused by loss-of-function mutations in both copies of the Esco2 ortholog of Eco1, are known collectively as the cohesinopathies [145]. As mentioned, many of the diverse developmental deficits in CdLS stem largely from gene dysregulation, but the molecular etiology of RBS/SC is poorly understood [146]. However, cells from both CdLS and RBS/SC individuals display increased sensitivity to DNA damage inducing agents [37,40,131,147,148]. Deficiencies in DNA repair would be predicted to cause increases in the frequency of cancer, or even immune deficiencies. Currently, there is insufficient data to know if this is the case, but cancer is responsible for only 2% of deaths in CdLS [149]. An increase in cancer, if it occurs, may be small and masked by the more frequent causes of morbidity associated with the structural birth defects. There is even less information regarding RBS/SC, but an RBS/SC mutation, recreated in budding yeast, shows that Eco1 promotes reciprocal crossing over after treatment with the radiomimetic bleomycin during mitotic growth [136].

Do DNA repair deficits or gene expression changes arising from cohesion factor mutations contribute to cancer progression?

A hallmark of cancer is aneuploidy, and reinforcement of cohesion in response to DNA damage, could be a way to prevent this. However, cohesion and chromosome segregation are the most robust of cohesin’s functions, and require less than 20% of normal cohesin levels [32,33]. On the other hand, the NIPBL adherin is important for survival after ionizing radiation treatment, and Rad21 haploinsufficiency impedes DNA repair and enhances gastrointestinal radiosensitivity in mice [150-152]. In addition, NIPBL mutations are found at high frequency in a panel of colon cancers, Rad21 alterations occur in breast, prostate cancer and leukemia, and Stag2 (SA) mutations are found in a variety of tumor types [103,153-156]. Thus even in the absence of overt cohesion defects, impaired DNA repair could contribute to mutagenic processes. Recent studies in yeast indicate that aneuploidy can cause defects in DNA repair, and thus it can be speculated that aneuploidy enhances the repair deficits associated with cohesion factor mutations [157].

Finally, it is also possible that altered gene expression caused with modest reductions in cohesin function could contribute to cancer progression. It has also been proposed that overexpression of Rad21, associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer, may influence disease progression by changes in gene expression [158].

Concluding remarks

As described above, like its role in chromosome segregation, cohesin’s ancient role in DNA repair, inherited from its bacterial ancestors, has been retained throughout evolution. We cannot, however, be sure that some aspects have not changed until the detailed mechanisms are elucidated, and we also do not yet know to what extent cohesin’s dosage-sensitive role in repair contributes to the etiology of cancer. It has also been revealed that cohesin has acquired more roles in gene regulation with increasing organismal complexity, to the point where even minor changes in cohesin activity can have drastic consequences for development. Elucidation of the mechanisms by which cohesin participates in DNA repair and gene regulation therefore remains of substantial relevance for human health.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marisa Bartolomei and Camilla Sjögren for helpful discussions, and Jennifer Gerton for comments on the manuscript. Research in the Dorsett laboratory is supported by grants from the NIH (GM055683, HD052860) and the Ström laboratory by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish research council and the Wiberg’s and Jeansson’s foundations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nasmyth K, Haering CH. Cohesin: its roles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivanov D, Nasmyth K. A topological interaction between cohesin rings and a circular minichromosome. Cell. 2005;122:849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanov D, Nasmyth K. A physical assay for sister chromatid cohesion in vitro. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasmyth K. Cohesin: a catenase with separate entry and exit gates? Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:1170–1177. doi: 10.1038/ncb2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gause M, Misulovin Z, Bilyeu A, Dorsett D. Dosage-sensitive regulation of cohesin chromosome binding and dynamics by Nipped-B, Pds5, and Wapl. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:4940–4951. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00642-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu B, Itoh T, Mishra A, Katoh Y, Chan KL, Upcher W, Godlee C, Roig MB, Shirahige K, Nasmyth K. ATP hydrolysis is required for relocating cohesin from sites occupied by its Scc2/4 loading complex. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu A, Revenkova E, Jessberger R. DNA interaction and dimerization of eukaryotic SMC hinge domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26233–26242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skibbens RV. Sticking a fork in cohesin--it’s not done yet! Trends Genet. 2011;27:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiyama T, Ladurner R, Schmitz J, Kreidl E, Schleiffer A, Bhaskara V, Bando M, Shirahige K, Hyman AA, Mechtler K, Peters JM. Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing Wapl. Cell. 2010;143:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckouët F, Hu B, Roig MB, Sutani T, Komata M, Uluocak P, Katis VL, Shirahige K, Nasmyth K. An Smc3 acetylation cycle is essential for establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borges V, Lehane C, Lopez-Serra L, Flynn H, Skehel M, Rolef Ben-Shahar T, Uhlmann F. Hos1 deacetylates Smc3 to close the cohesin acetylation cycle. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong B, Lu S, Gerton JL. Hos1 is a lysine deacetylase for the Smc3 subunit of cohesin. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1660–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuinness BE, Hirota T, Kudo NR, Peters JM, Nasmyth K. Shugoshin prevents dissociation of cohesin from centromeres during mitosis in vertebrate cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e86. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNairn AJ, Gerton JL. Intersection of ChIP and FLIP, genomic methods to study the dynamics of the cohesin proteins. Chromosome Res. 2009;17:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-9007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerlich D, Koch B, Dupeux F, Peters JM, Ellenberg J. Live-cell imaging reveals a stable cohesin-chromatin interaction after but not before DNA replication. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1571–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn EF, Megee PC, Yu HG, Mistrot C, Ünal E, Koshland DE, DeRisi JL, Gerton JL. Genome-wide mapping of the cohesin complex in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lengronne A, Katou Y, Mori S, Yokobayashi S, Kelly GP, Itoh T, Watanabe Y, Shirahige K, Uhlmann F. Cohesin relocation from sites of chromosomal loading to places of convergent transcription. Nature. 2004;430:573–578. doi: 10.1038/nature02742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gullerova M, Proudfoot NJ. Cohesin complex promotes transcriptional termination between convergent genes in S. pombe. Cell. 2008;132:983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt CK, Brookes N, Uhlmann F. Conserved features of cohesin binding along fission yeast chromosomes. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R52. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-5-r52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gause M, Webber HA, Misulovin Z, Haller G, Rollins RA, Eissenberg JC, Bickel SE, Dorsett D. Functional links between Drosophila Nipped-B and cohesin in somatic and meiotic cells. Chromosoma. 2008;117:51–66. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0125-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misulovin Z, Schwartz YB, Li XY, Kahn TG, Gause M, MacArthur S, Fay JC, Eisen MB, Pirrotta V, Biggin MD, Dorsett D. Association of cohesin and Nipped-B with transcriptionally active regions of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Chromosoma. 2008;117:89–102. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacAlpine HK, Gordân R, Powell SK, Hartemink AJ, MacAlpine DM. Drosophila ORC localizes to open chromatin and marks sites of cohesin complex loading. Genome Res. 2010;20:201–211. doi: 10.1101/gr.097873.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauli A, van Bemmel JG, Oliveira RA, Itoh T, Shirahige K, van Steensel B, Nasmyth K. A direct role for cohesin in gene regulation and ecdysone response in Drosophila salivary glands. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1787–1798. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, Zhan Y, Orlando DA, van Berkum NL, Ebmeier CC, Goossens J, Rahl PB, Levine SS, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2011;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Zhang Z, Bando M, Itoh T, Deardorff MA, Clark D, Kaur M, Tandy S, Kondoh T, Rappaport E, et al. Transcriptional dysregulation in NIPBL and cohesin mutant human cells. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nitzsche A, Rogacz M, Matarese F, Janssen-Megens EM, Hubner NC, Schulz H, de Vries I, Ding L, Huebner N, Mann M, Stunnenberg HG, Buchholz F. RAD21 cooperates with pluripotency transcription factors in the maintenance of embryonic stem cell identity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, Leleu M, Sauer S, Gregson HC, Jarmuz A, Canzonetta C, Webster Z, Nesterova T, Cobb BS, Yokomori K, Dillon N, Aragon L, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell. 2008;132:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubio ED, Reiss DJ, Welcsh PL, Disteche CM, Filippova GN, Baliga NS, Aebersold R, Ranish JA, Krumm A. CTCF physically links cohesin to chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:8309–8314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801273105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stedman W, Kang H, Lin S, Kissil JL, Bartolomei MS, Lieberman PM. Cohesins localize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and at cellular c-myc and H19/Igf2 insulators. EMBO J. 2008;27:654–666. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, Bando M, Koch B, Schirghuber E, Tsutsumi S, Nagae G, Ishihara K, Mishiro T, Yahata K, Imamoto F, Aburatani H, Nakao M, Imamoto N, Maeshima K, Shirahige K, Peters JM. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature. 2008;451:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature06634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao T, Wallace J, Felsenfeld G. Specific sites in the C terminus of CTCF interact with the SA2 subunit of the cohesin complex and are required for cohesin-dependent insulation activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:2174–2183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05093-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heidinger-Pauli JM, Mert O, Davenport C, Guacci V, Koshland D. Systematic reduction of cohesin differentially affects chromosome segregation, condensation, and DNA repair. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaaf CA, Misulovin Z, Sahota G, Siddiqui AM, Schwartz YB, Kahn TG, Pirrotta V, Gause M, Dorsett D. Regulation of the Drosophila Enhancer of split and invected-engrailed gene complexes by sister chromatid cohesion proteins. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krantz ID, McCallum J, DeScipio C, Kaur M, Gillis LA, Yaeger D, Jukofsky L, Wasserman N, Bottani A, Morris CA, et al. Cornelia de Lange syndrome is caused by mutations in NIPBL, the human homolog of Drosophila melanogaster Nipped-B. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:631–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tonkin ET, Wang TJ, Lisgo S, Bamshad MJ, Strachan T. NIPBL, encoding a homolog of fungal Scc2-type sister chromatid cohesion proteins and fly Nipped-B, is mutated in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:636–641. doi: 10.1038/ng1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaur M, DeScipio C, McCallum J, Yaeger D, Devoto M, Jackson LG, Spinner NB, Krantz ID. Precocious sister chromatid separation (PSCS) in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;138:27–31. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vrouwe MG, Elghalbzouri-Maghrani E, Meijers M, Schouten P, Godthelp BC, Bhuiyan ZA, Redeker EJ, Mannens MM, Mullenders LH, Pastink A, et al. Increased DNA damage sensitivity of Cornelia de Lange syndrome cells: evidence for impaired recombinational repair. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1478–1487. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deardorff MA, Kaur M, Yaeger D, Rampuria A, Korolev S, Pie J, Gil-Rodríguez C, Arnedo M, Loeys B, Kline AD, et al. Mutations in cohesin complex members SMC3 and SMC1A cause a mild variant of Cornelia de Lange syndrome with predominant mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:485–494. doi: 10.1086/511888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musio A, Selicorni A, Focarelli ML, Gervasini C, Milani D, Russo S, Vezzoni P, Larizza L. X-linked Cornelia de Lange syndrome owing to SMC1L1 mutations. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:528–530. doi: 10.1038/ng1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Revenkova E, Focarelli ML, Susani L, Paulis M, Bassi MT, Mannini L, Frattini A, Delia D, Krantz I, Vezzoni P, et al. Cornelia de Lange syndrome mutations in SMC1A or SMC3 affect binding to DNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:418–427. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorsett D, Eissenberg JC, Misulovin Z, Martens A, Redding B, McKim K. Effects of sister chromatid cohesion proteins on cut gene expression during wing development in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:4743–4753. doi: 10.1242/dev.02064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horsfield JA, Anagnostou SH, Hu JK, Cho KH, Geisler R, Lieschke G, Crosier KE, Crosier PS. Cohesin-dependent regulation of Runx genes. Development. 2007;134:2639–2649. doi: 10.1242/dev.002485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawauchi S, Calof AL, Santos R, Lopez-Burks ME, Young CM, Hoang MP, Chua A, Lao T, Lechner MS, Daniel JA, et al. Multiple organ system defects and transcriptional dysregulation in the Nipbl(+/-) mouse, a model of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rollins RA, Morcillo P, Dorsett D. Nipped-B, a Drosophila homologue of chromosomal adherins, participates in activation by remote enhancers in the cut and Ultrabithorax genes. Genetics. 1999;152:577–593. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rollins RA, Korom M, Aulner N, Martens A, Dorsett D. Drosophila Nipped-B protein supports sister chromatid cohesion and opposes the stromalin/Scc3 cohesion factor to facilitate long-range activation of the cut gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:3100–3111. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3100-3111.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang B, Jain S, Song H, Fu M, Heuckeroth RO, Erlich JM, Jay PY, Milbrandt J. Mice lacking sister chromatid cohesion protein PDS5B exhibit developmental abnormalities reminiscent of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Development. 2007;134:3191–3201. doi: 10.1242/dev.005884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang B, Chang J, Fu M, Huang J, Kashyap R, Salavaggione E, Jain S, Kulkarni S, Deardorff MA, Uzielli ML, et al. Dosage effects of cohesin regulatory factor PDS5 on mammalian development: implications for cohesinopathies. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pauli A, Althoff F, Oliveira RA, Heidmann S, Schuldiner O, Lehner CF, Dickson BJ, Nasmyth K. Cell-type-specific TEV protease cleavage reveals cohesin functions in Drosophila neurons. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seitan VC, Hao B, Tachibana-Konwalski K, Lavagnolli T, Mira-Bontenbal H, Brown KE, Teng G, Carroll T, Terry A, Horan K, et al. A role for cohesin in T-cell-receptor rearrangement and thymocyte differentiation. Nature. 2011;476:467–471. doi: 10.1038/nature10312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schuldiner O, Berdnik D, Levy JM, Wu JS, Luginbuhl D, Gontang AC, Luo L. piggyBac-based mosaic screen identifies a postmitotic function for cohesin in regulating developmental axon pruning. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donze D, Adams CR, Rine J, Kamakaka RT. The boundaries of the silenced HMR domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1999;13:698–708. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donze D, Kamakaka RT. RNA polymerase III and RNA polymerase II promoter complexes are heterochromatin barriers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2001;20:520–531. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang CR, Wu CS, Hom Y, Gartenberg MR. Targeting of cohesin by transcriptionally silent chromatin. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3031–3042. doi: 10.1101/gad.1356305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.D’Ambrosio C, Schmidt CK, Katou Y, Kelly G, Itoh T, Shirahige K, Uhlmann F. Identification of cis-acting sites for condensin loading onto budding yeast chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2215–2227. doi: 10.1101/gad.1675708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dubey RN, Gartenberg MR. A tDNA establishes cohesion of a neighboring silent chromatin domain. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2150–2160. doi: 10.1101/gad.1583807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu CS, Chen YF, Gartenberg MR. Targeted sister chromatid cohesion by Sir2. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gard S, Light W, Xiong B, Bose T, McNairn AJ, Harris B, Fleharty B, Seidel C, Brickner JH, Gerton JL. Cohesinopathy mutations disrupt the subnuclear organization of chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 2009;187:455–462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skibbens RV, Marzillier J, Eastman L. Cohesins coordinate gene transcriptions of related function within Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1601–1606. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernard P, Maure JF, Partridge JF, Genier S, Javerzat JP, Allshire RC. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science. 2001;294:2539–2542. doi: 10.1126/science.1064027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nonaka N, Kitajima T, Yokobayashi S, Xiao G, Yamamoto M, Grewal SI, Watanabe Y. Recruitment of cohesin to heterochromatic regions by Swi6/HP1 in fission yeast. Natl. Cell Biol. 2002;4:89–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dheur S, Saupe SJ, Genier S, Vazquez S, Javerzat JP. Role for cohesin in the formation of a heterochromatic domain at fission yeast subtelomeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:1088–1097. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01290-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zeng W, de Greef JC, Chen YY, Chien R, Kong X, Gregson HC, Winokur ST, Pyle A, Robertson KD, Schmiesing JA, et al. Specific loss of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation and HP1gamma/cohesin binding at D4Z4 repeats is associated with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD) PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koch B, Kueng S, Ruckenbauer C, Wendt KS, Peters JM. The Suv39h-HP1 histone methylation pathway is dispensable for enrichment and protection of cohesin at centromeres in mammalian cells. Chromosoma. 2008;117:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lechner MS, Schultz DC, Negorev D, Maul GG, Rauscher FJ., 3rd. The mammalian heterochromatin protein 1 binds diverse nuclear proteins through a common motif that targets the chromoshadow domain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;331:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oka Y, Suzuki K, Yamauchi M, Mitsutake N, Yamashita S. Recruitment of the cohesin loading factor NIPBL to DNA double-strand breaks depends on MDC1, RNF168 and HP1γ in human cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;411:762–767. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strübbe G, Popp C, Schmidt A, Pauli A, Ringrose L, Beisel C, Paro R. Polycomb purification by in vivo biotinylation tagging reveals cohesin and Trithorax group proteins as interaction partners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:5572–5577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007916108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hallson G, Syrzycka M, Beck SA, Kennison JA, Dorsett D, Page SL, Hunter SM, Keall R, Warren WD, Brock HW, et al. The Drosophila cohesin subunit Rad21 is a trithorax group (trxG) protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:12405–12410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801698105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kennison JA, Tamkun JW. Dosage-dependent modifiers of Polycomb and Antennapedia mutations in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:8136–8140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dorsett D. Cohesin: genomic insights into controlling gene transcription and development. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011;21:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Enderle D, Beisel C, Stadler MB, Gerstung M, Athri P, Paro R. Polycomb preferentially targets stalled promoters of coding and noncoding transcripts. Genome Res. 2011;21:216–226. doi: 10.1101/gr.114348.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fay A, Misulovin Z, Li J, Schaaf CA, Gause M, Gilmour DS, Dorsett D. Cohesin selectively binds and regulates genes with paused RNA polymerase. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:1624–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levine M. Paused RNA polymerase II as a developmental checkpoint. Cell. 2011;145:502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang H, Lieberman PM. Mechanism of glycyrrhizic acid inhibition of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: disruption of CTCF-cohesin-mediated RNA polymerase II pausing and sister chromatid cohesion. J. Virol. 2011;85:11159–11169. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00720-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nechaev S, Adelman K. Pol II waiting in the starting gates: Regulating the transition from transcription initiation into productive elongation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1809:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith E, Lin C, Shilatifard A. The super elongation complex (SEC) and MLL in development and disease. Genes Dev. 2011;25:661–672. doi: 10.1101/gad.2015411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kharchenko PV, Alekseyenko AA, Schwartz YB, Minoda A, Riddle NC, Ernst J, Sabo PJ, Larschan E, Gorchakov AA, Gu T, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:480–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rhodes JM, Bentley FK, Print CG, Dorsett D, Misulovin Z, Dickinson EJ, Crosier KE, Crosier PS, Horsfield JA. Positive regulation of c-Myc by cohesin is direct, and evolutionarily conserved. Dev. Biol. 2010;344:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chien R, Zeng W, Kawauchi S, Bender MA, Santos R, Gregson HC, Schmiesing JA, Newkirk DA, Kong X, Ball AR, Jr., et al. Cohesin mediates chromatin interactions that regulate mammalian β-globin expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:17870–17878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.207365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Borggrefe T, Yue X. Interactions between subunits of the Mediator complex with gene-specific transcription factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;22:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Function and regulation of the Mediator complex. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011;21:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schmidt D, Ross-Schwalie PC, Innes CS, Hurtado A, Brown GD, Carroll JS, Flicek P, Odom DT. A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription. Genome Res. 2010;20:578–588. doi: 10.1101/gr.100479.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ohlsson R, Bartkuhn M, Renkawitz R. CTCF shapes chromatin by multiple mechanisms: the impact of 20 years of CTCF research on understanding the workings of chromatin. Chromosoma. 2010;119:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s00412-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Degner SC, Verma-Gaur J, Wong TP, Bossen C, Iverson GM, Torkamani A, Vettermann C, Lin YC, Ju Z, Schulz D, Murre CS, et al. CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the Igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:9566–9571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hadjur S, Williams LM, Ryan NK, Cobb BS, Sexton T, Fraser P, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M. Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus. Nature. 2009;460:410–413. doi: 10.1038/nature08079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hou C, Dale R, Dean A. Cell type specificity of chromatin organization mediated by CTCF and cohesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:3651–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kang H, Wiedmer A, Yuan Y, Robertson E, Lieberman PM. Coordination of KSHV latent and lytic gene control by CTCF-cohesin mediated chromosome conformation. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002140. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim YJ, Cecchini KR, Kim TH. Conserved, developmentally regulated mechanism couples chromosomal looping and heterochromatin barrier activity at the homeobox gene A locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:7391–7396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018279108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mishiro T, Ishihara K, Hino S, Tsutsumi S, Aburatani H, Shirahige K, Kinoshita Y, Nakao M. Architectural roles of multiple chromatin insulators at the human apolipoprotein gene cluster. EMBO J. 2009;28:1234–1245. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nativio R, Wendt KS, Ito Y, Huddleston JE, Uribe-Lewis S, Woodfine K, Krueger C, Reik W, Peters JM, Murrell A. Cohesin is required for higher-order chromatin conformation at the imprinted IGF2-H19 locus. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Majumder P, Boss JM. Cohesin regulates MHC class II genes through interactions with MHC class II insulators. J. Immunol. 2011;187:4236–4244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lin S, Ferguson-Smith AC, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS. Nonallelic transcriptional roles of CTCF and cohesins at imprinted loci. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:3094–3104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01449-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gerasimova TI, Lei EP, Bushey AM, Corces VG. Coordinated control of dCTCF and gypsy chromatin insulators in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mohan M, Bartkuhn M, Herold M, Philippen A, Heinl N, Bardenhagen I, Leers J, White RA, Renkawitz-Pohl R, Saumweber H, Renkawitz R. The Drosophila insulator proteins CTCF and CP190 link enhancer blocking to body patterning. EMBO J. 2007;26:4203–4214. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moon H, Filippova G, Loukinov D, Pugacheva E, Chen Q, Smith ST, Munhall A, Grewe B, Bartkuhn M, Arnold R, et al. CTCF is conserved from Drosophila to humans and confers enhancer blocking of the Fab-8 insulator. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:165–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ohnishi T, Mori E, Takahashi A. DNA double-strand breaks: their production, recognition, and repair in eukaryotes. Mutat. Res. 2009;669:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.San Filippo J, Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brunborg G, Williamson DH. The relevance of the nuclear division cycle to radiosensitivity in yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1978;162:277–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00268853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sjögren C, Nasmyth K. Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:991–995. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Graumann PL, Knust T. Dynamics of the bacterial SMC complex and SMC-like proteins involved in DNA repair. Chromosome Res. 2009;17:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-9014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Birkenbihl RP, Subramani S. Cloning and characterization of rad21 an essential gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in DNA double-strand-break repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6605–6611. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jessberger R, Podust V, Hübscher U, Berg P. A mammalian protein complex that repairs double-strand breaks and deletions by recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:15070–15079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sonoda E, Matsusaka T, Morrison C, Vagnarelli P, Hoshi O, Ushiki T, Nojima K, Fukagawa T, Waizenegger IC, Peters JM, et al. Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 is required for sister chromatid cohesion and kinetochore function in vertebrate cells. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Atienza JM, Roth RB, Rosette C, Smylie KJ, Kammerer S, Rehbock J, Ekblom J, Dennisenko MF. Suppression of RAD21 gene expression decreases cell growth and enhances cytotoxicity of etoposide and bleomycin in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005;4:361–368. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schmitz J, Watrin E, Lenart P, Mechtler K, Peters JM. Sororin is required for stable binding of cohesin to chromatin and for sister chromatid cohesion in interphase. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Callegari AJ, Kelly TJ. Shedding light on the DNA damage checkpoint. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:660–666. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim ST, Xu B, Kastan MB. Involvement of the cohesin protein, Smc1, in Atm-dependent and independent responses to DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2002;16:560–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.970602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kitagawa R, Bakkenist CJ, McKinnon PJ, Kastan MB. Phosphorylation of SMC1 is a critical downstream event in the ATM-NBS1-BRCA1 pathway. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1423–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luo H, Li Y, Mu JJ, Zhang J, Tonaka T, Hamamori Y, Jung SY, Wang Y, Qin J. Regulation of intra-S phase checkpoint by ionizing radiation (IR)-dependent and IR-independent phosphorylation of SMC3. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:19176–19183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802299200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yazdi PT, Wang Y, Zhao S, Patel N, Lee EY, Qin J. SMC1 is a downstream effector in the ATM/NBS1 branch of the human S-phase checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2002;16:571–582. doi: 10.1101/gad.970702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Watrin E, Peters JM. The cohesin complex is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:2625–2635. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lightfoot J, Testori S, Barroso C, Martinez-Perez E. Loading of meiotic cohesin by SCC-2 is required for early processing of DSBs and for the DNA damage checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:1421–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sjögren C, Nasmyth K. Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:991–995. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim JS, Krasieva TB, LaMorte V, Taylor AM, Yokomori K. Specific recruitment of human cohesin to laser-induced DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45149–45153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bekker-Jensen S, Lukas C, Kitagawa R, Melander F, Kastan MB, Bartek J, Lukas J. Spatial organization of the mammalian genome surveillance machinery in response to DNA strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:195–206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Potts PR, Porteus MH, Yu H. Human SMC5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid homologous recombination by recruiting the SMC1/3 cohesin complex to double-strand breaks. EMBO J. 2006;25:3377–3388. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ström L, Lindroos HB, Shirahige K, Sjögren C. Postreplicative recruitment of cohesin to double-strand breaks is required for DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2004;16:1003–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ünal E, Arbel-Eden A, Sattler U, Shroff R, Lichten M, Haber JE, Koshland D. DNA damage response pathway uses histone modification to assemble a double-strand break-specific cohesin domain. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ström L, Sjögren C. DNA Damage-Induced Cohesion. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:536–539. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.4.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ström L, Karlsson C, Lindroos HB, Wedahl S, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Sjögren C. Postreplicative formation of cohesion is required for repair and induced by a single DNA break. Science. 2007;317:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1140649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ünal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Koshland D. DNA double-strand breaks trigger genome-wide sister-chromatid cohesion through Eco1 (Ctf7) Science. 2007;317:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1140637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heidinger-Pauli JM, Ünal E, Guacci V, Koshland D. The kleisin subunit of cohesin dictates damage-induced cohesion. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ben-Shahar TR, Heeger S, Lehane C, East P, Flynn H, Skehel M, Uhlmann F. Eco1-dependent cohesin acetylation during establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.1157774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Heidinger-Pauli JM, Ünal E, Koshland D. Distinct targets of the Eco1 acetyltransferase modulate cohesion in S phase and in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rowland BD, Roig MB, Nishino T, Kurze A, Uluocak P, Mishra A, Beckouët F, Underwood P, Metson J, Imre R, et al. Building sister chromatid cohesion: smc3 acetylation counteracts an antiestablishment activity. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sutani T, Kawaguchi T, Kanno R, Itoh T, Shirahige K. Budding yeast Wpl1(Rad61)-Pds5 complex counteracts sister chromatid cohesion-establishing reaction. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ünal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Kim W, Guacci V, Onn I, Gygi SP, Koshland DE. A molecular determinant for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1157880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang J, Shi X, Li Y, Kim BJ, Jia J, Huang Z, Yang T, Fu X, Jung SY, Wang Y, et al. Acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 is required for S phase sister chromatid cohesion in both human and yeast. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lyons NA, Morgan DO. Cdk1-dependent destruction of Eco1 prevents cohesion establishment after S phase. Mol. Cell. 2011;42:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dodson H, Morrison CG. Increased sister chromatid cohesion and DNA damage response factor localization at an enzyme-induced DNA double-strand break in vertebrate cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6054–6063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Watanabe K, Pacher M, Dukowic S, Schubert V, Puchta H, Schubert I. The structural maintenance of chromosomes 5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid alignment and homologous recombination after DNA damage in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2688–2699. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.van der Lelij P, Godthelp BC, van Zon W, van Gosliga D, Oostra AB, Steltenpool J, de Groot J, Scheper RJ, Wolthuis RM, Waisfisz Q, et al. The cellular phenotype of Roberts syndrome fibroblasts as revealed by ectopic expression of ESCO2. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sjögren C, Ström L. S-phase and DNA damage activated establishment of sister chromatid cohesion--importance for DNA repair. Exp. Cell Res. 2010;316:1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nagao K, Adachi Y, Yanagida M. Separase-mediated cleavage of cohesin at interphase is required for DNA repair. Nature. 2004;430:1044–1048. doi: 10.1038/nature02803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kim BJ, Li Y, Zhang J, Xi Y, Yang T, Jung SY, Pan X, Chen R, Li W, Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide reinforcement of cohesin binding at pre-existing cohesin sites in response to ionizing radiation in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22784–22792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.134577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Toth A, Ciosk R, Uhlmann F, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K. Yeast cohesin complex requires a conserved protein, Eco1p(Ctf7), to establish cohesion between sister chromatids during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1999;13:320–333. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lu S, Goering M, Gard S, Xiong B, McNairn AJ, Jaspersen SL, Gerton JL. Eco1 is important for DNA damage repair in S. cerevisiae. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3315–3327. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]