Abstract

Undue influence of shape or weight on self-evaluation — referred to as overvaluation — is a core feature across eating disorders, but is not a diagnostic requirement for binge-eating disorder (BED). This study examined overvaluation of shape/weight in ethnically diverse obese patients with BED seeking treatment in primary care. Participants were a consecutive series of 142 (105 female and 37 male) participants with BED; 43% were Caucasian, 37% were African-American, 13% were Hispanic-American, and 7% were of “other” ethnicity. Participants categorized with overvaluation (N=97; 68%) versus without clinical overvaluation (N=45; 32%) did not differ significantly in ethnicity/race, age, gender, body mass index, or binge-eating frequency. The overvaluation group had significantly greater levels of eating-disorder psychopathology, poorer psychological functioning (higher depression, lower self-esteem), and greater anxiety disorder co-morbidity than the group who did not overvalue their shape/weight. The greater eating-disorder and psychological disturbance levels in the overvaluation group relative to the non-overvaluation group persisted after controlling for psychiatric co-morbidity. Our findings, based on an ethnically diverse series of patients seeking treatment in general primary-care settings, are consistent with findings from specialist clinics and suggest that overvaluation does not simply reflect concerns commensurate with being obese or with frequency of binge-eating, but is strongly associated with heightened eating-related psychopathology and psychological distress. Overvaluation of shape/weight warrants consideration as a diagnostic specifier for BED as it provides important information about severity.

Keywords: eating disorders, body image, obesity, ethnicity, race

Binge eating disorder (BED), a research category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; APA, 1994), is characterized by recurrent binge eating without inappropriate compensatory weight-control behaviors. BED is more prevalent than two other eating disorders (ED), bulimia nervosa (BN) and anorexia nervosa (AN) (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Critical reviews have concluded that sufficient evidence exists for BED to warrant its inclusion as a formal diagnosis in the DSM-5 (Striegel-Moore & Franko, 2008) and it is included as such in the current proposal for DSM-5.

As we move toward the DSM-5, a pressing question regarding BED is whether further revisions to its criteria would improve the construct (Masheb & Grilo, 2000). The Eating Disorder Work Group’s current proposal for DSM-5, in addition to making BED a formal diagnosis, revised the binge-eating frequency and duration stipulations to once-weekly on average for past three months; this revision – intended partly to parallel the criteria for bulimia nervosa – follows convergent empirical evidence (Striegel-Moore & Franko, 2008). Interestingly, the BED diagnosis includes a “marked distress” criterion, recently supported in an empirical study (Grilo & White, 2011), but – in contrast to the other eating disorder diagnoses – does not include a cognitive criterion pertaining to body image. DSM-IV (and the current proposal for DSM-5) criteria for BN, but not for BED, require the presence of overvaluation of shape or weight, or the “undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation” (APA, 1994, p. 545).

Overvaluation of shape/weight is a related - but distinct - construct from the more general concepts of body dissatisfaction and shape/weight concerns. Overvaluation, which is central to understanding the nature of eating-disorder psychopathology, is frequently confused with body dissatisfaction (Fairburn et al., 2003). Most simply, although many persons may be dissatisfied with their appearance (shape or weight), many fewer define their self-worth primarily based on their shape/weight (Hrabosky et al., 2007). The distinction between overvaluation of shape/weight versus body dissatisfaction has been demonstrated by factor-analytic (Grilo, Crosby et al., 2010), longitudinal (Masheb & Grilo, 2003), and latent genetic and environmental risk factor analyses in twin studies (Wade, Zhu, & Martin, 2011).

It is established that patients with BED and BN are similar in terms of their shape/weight concerns despite substantial differences in mean weights (Ahrberg, Trojca, Nasrawi, & Vocks, in press; Masheb & Grilo, 2000). Recently, research comparing these two eating disorders has focused more precisely on the specific construct of overvaluation of shape/weight. One study (Mond et al., 2007) supported the addition of overvaluation as a required criterion for BED. More recently, a series of complementary studies has provided convergent empirical evidence suggesting that overvaluation warrants consideration as a diagnostic specifier – as it provides important information about severity within BED – rather than as a required criterion, because that would result in the exclusion of many persons with clinically significant eating-pathology (Goldschmidt et al., 2011; Grilo, Crosby et al., 2009; Grilo, Hrabosky et al., 2008; Grilo, Masheb, & White, 2010; Hrabosky et al; 2007). For example, Grilo and colleagues (2008), in a clinical sample of 210 overweight patients assessed at a specialty research clinic using the Eating Disorder Examination interview (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993), found that participants with BED with overvaluation had significantly greater eating-disorder psychopathology and depression levels than BED participants without overvaluation. Importantly, both BED groups (regardless of degree of overvaluation) had significantly greater levels of eating-disorder psychopathology and depression than the overweight comparison group.

The present study examined overvaluation of shape/weight in an ethnically diverse sample of obese patients with BED seeking treatment in primary care. This is important for several reasons. First, the existing literature is based primarily on clinical samples of treatment-seekers from specialist research clinics (Grilo, Crosby et al., 2009; Grilo, Hrabosky, et 2008; Hrabosky et al., 2007) and findings may not generalize adequately due to potential confounds associated with various clinic biases (Fairburn, Welch et al., 1996; Grilo, Lozano, & Masheb, 2005; Pike, Dohm, Striegel-Moore, Wilfley, & Fairburn, 2001). The remaining literature is based on various community recruitment methods (Goldschmidt et al., 2011; Mond et al., 2007; Grilo et al., 2010) and the generalizability of those samples to the DSM-5 – which is intended for clinicians working with “real world” clinical patients – is also uncertain. Second, the existing literature is based on study groups comprised predominately of Caucasian participants and findings may not generalize to more diverse groups comprising different ethnic composition (Franko et al., in press). Recent epidemiological studies have found that African American and Hispanic groups have comparable-to-higher prevalence rates of binge-eating than Caucasians (Alegria et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2011). In sharp contrast to such prevalence data, African-American and Hispanic persons have been vastly under-represented in studies of BED (Franko et al., in press), including those of overvaluation of shape/weight noted above. Epidemiological studies of binge-eating problems have documented that minority groups have lower mental health utilization rates than whites and receive most of their health care from generalist or primary care settings rather than specialists (Marques et al., 2011). Third, despite being common in primary care settings and associated with increased health service utilization and health problems in such settings (Johnson, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001), persons with BED often are missed by general healthcare providers (Crow, Levine, Thuras, & Mitchell, 2004; Mond, Myers, Crosby, Hay, & Mitchell, 2010) resulting in little available knowledge about the needs of this specific patient group.

Thus, this study of overvaluation of shape/weight performed in primary care is intend to complement and extend the existing literature in several ways including the potential to contribute to the small literature on ethnicity and BED. Given recent findings from epidemiological (Marques et al., 2011) and specialty clinic (Franko et al., in press) studies that there appear to be few differences in binge eating and body image across ethnic/racial groups, we hypothesized that overvaluation of shape/weight would have a similar distribution and clinical significance (i.e., signals greater disturbances) in this ethnically-diverse obese patient group with BED seeking treatment in general primary care settings.

Method

Participants

Participants were a consecutive series of 142 patients who were respondents for a treatment study for obese persons who binge eat being performed in primary care settings in a large university-based medical health-care center in an urban setting. Participants were required to be obese (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30) and meet proposed DSM-5 criteria for BED. Unlike DSM-IV criteria for BED, which requires a minimum frequency of twice-weekly binge-eating with a six-month duration, the DSM-5 stipulates a minimum frequency of once-weekly binge-eating with a three-month duration. Recruitment for the treatment study (designed as an “effectiveness” study) was intended to enhance generalizability and therefore included relatively few exclusionary criteria. Notable exclusion criteria included current antidepressant therapy, severe psychiatric problems (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and current substance use disorder), severe medical problems (cardiac disease, liver disease), and uncontrolled hypertension, thyroid disease, or diabetes. The study had full IRB review and approval and all participants provided written informed consent.

Overall, participants had a mean age of 43.6 years (SD = 11.3) and a mean BMI of 38.5 kg/m2 (SD = 5.5). Seventy-four percent (N=105) were female and 26% (N=37) were male. In terms of ethnicity/race, 43% (N=61) were Caucasian, 37% (N=52) were African-American, 13% (N=19) were Hispanic-American, and 7% (N=10) were of “other” minority/ethnic groups.

Assessments and Measures

Participants were assessed by doctoral-level research-clinicians who were trained in the administration of the study’s measures. BED and axis I psychiatric diagnoses were determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P) (First et al., 1996)) and confirmed with findings from the Eating Disorder Examination (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) which was used to assess eating-disorder psychopathology. Participants completed a battery of self-report measures and measurements of weight and height were obtained using a high-capacity digital scale.

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) interview focuses on the previous 28 days, except for diagnostic items that are rated for relevant duration stipulations. The EDE assesses the frequency of different forms of overeating, including objective bulimic episodes (i.e., OBEs; eating unusually large quantities of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control) which corresponds to the DSM-IV and DSM-5 criterion for binge-eating, and subjective bulimic episodes (i.e., SBEs; eating small quantities of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control). The EDE comprises four subscales: Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, and Weight Concern. The items assessing ED features for the four scales are rated on a 7-point forced-choice format (0 to 6), with higher scores reflecting greater severity or frequency. The EDE, an established method for assessing the specific features of eating disorders (Grilo et al., 2001a, Grilo et al., 2001b) has shown good inter-rater and test-retest reliability with individuals with BED (Grilo, Masheb, Lozano-Blanco, & Barry, 2004) and diverse ethnic groups (Grilo, Lozano, & Elder, 2005). In the present study, inter-rater (N=34 ratings of taped interviews) reliability of the EDE was excellent. Inter-rater reliability intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) for OBE and SBE ranged from .83 (for episodes) to .90 (for days); for EDE scales, ICCs were: 0.92 (restraint), 0.71 (eating concern), 0.90 (weight concern), and 0.91 (shape concern).

Self-evaluation unduly influenced by shape and weight was measured using two specific items from the EDE: “Over the past four weeks, has your shape influenced how you feel about (judge, think, evaluate) yourself as a person?” and “Over the past 4 weeks has your weight influenced how you feel about (judge, think, evaluate) yourself as a person?” Given the complexity of these concepts, a second probe is used as a starting point for ensuring that participants understand these items (“If you imagine the things which influence how you feel about (judge, think, evaluate) yourself – such as your performance at work, being a parent, your marriage, how you get along with other people – and put these things in order of importance, where does your shape (or weight) fit in?”). The two overvaluation items are rated on a 7-point forced-choice scale anchored with 0 (No importance) to 6 (Supreme importance: nothing is more important in the person’s scheme for self-evaluation) in reference to each of the past three months. In this study, inter-rater reliability ICCs, determined using N=32 cases, were .95 and .81 for shape and weight overvaluation, respectively.

A composite shape/weight overvaluation value was created based on mean scores of these two items for the past four weeks consistent with prior studies with BED and BN (Grilo et al., 2008; Grilo, Crosby, et al., 2009). Following Fairburn and Cooper’s (1993) suggested clinical cut-off score of 4 (i.e., moderate importance), participants were categorized as experiencing either clinical or subclinical overvaluation. The clinical overvaluation group included individuals who reported that their shape and/or weight are high on the list of things that influence their self-evaluation (i.e., score ≥ 4 on either overvaluation item). The subclinical overvaluation group included individuals who reported either no influence or, only a mild influence of shape/weight on their self-evaluation (i.e., score < 4 on both overvaluation items).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987) is a widely used 21-item measure of depressive symptoms. The BDI also taps a broad range of negative affect - not just depressive affect (Watson & Clark, 1984) - and therefore is a useful marker for broad psychosocial distress (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001c). Studies with diverse clinical samples have reported good internal consistency (α = .81 to .86), test-retest reliability (r = .48 to .86), and convergent validity with clinician ratings (r = .60 to .72; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988).

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965) is a well-established 10-item measure of global self-esteem, with good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Rosenberg, 1965) and good validity in disordered-eating groups (Griffith et al., 1999).

Results

Dimensional Analyses of Overvaluation of Shape and Weight

Overvaluation dimensional scores were not significantly associated with age (r = −0.07, p = 0.41) or gender (male M = 3.3 (SD = 1.9) versus female M = 3.6 (SD = 2.0); F(1, N=142) = 0.18, p = 0.67). Overvaluation scores did not differ significantly across different ethnic/racial groups (Caucasian group M = 3.8 (SD = 1.65), African-American group M = 3.2 (SD = 1.9), Hispanic-American group M = 3.7 (SD = 2.5), “other” group M = 3.1 (SD = 2.4)) regardless of whether ANOVAs compared the four groups (F(3, N=142) = 1.04, p = 0.38) or three groups (Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic-American plus “other” (F(2, N=142) = 1.21, p = 0.30).

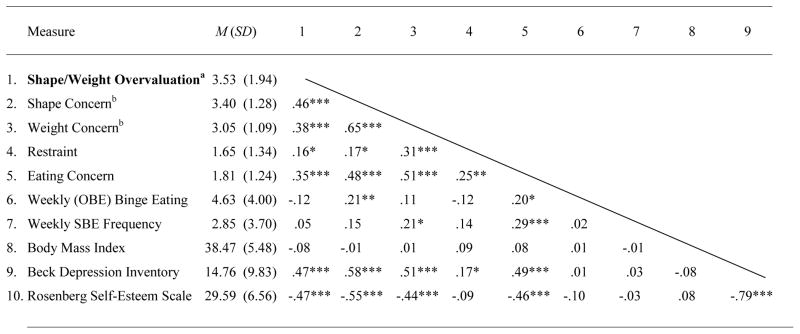

Table 1 provides overall descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for the measures. Overvaluation of shape/weight was significantly correlated with all clinical measures, with two notable exceptions: overvaluation was not correlated with BMI or with binge-eating frequency.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among the Dimensional Clinical Measures (N=142)

|

Overall, participants reported shape overvaluation (3.62 ± 2.03) and weight overvaluation (3.44 ± 2.03) in the moderate range. Consistent with previous studies (Hrabosky et al., 2007; Grilo et al., 2008), analyses performed on the shape and weight overvaluation items separately revealed essentially indistinguishable findings and therefore we report final analyses performed using the composite shape/weight overvaluation item.

The EDE Shape Concern and Weight Concern scale scores were calculated without their respective overvaluation items included in the interview’s standard scoring methods. If the overvaluation items were included, the means and standard deviations of these scales would be 3.43 ± 1.26 (Shape Concern) and 3.12 ± 1.10 (Weight Concern).

Note: OBE = objective bulimic episodes; SBE = subjective bulimic episodes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Categorical Analyses: Demographic and Psychiatric Characteristics of Overvaluation

Of the 142 participants, 68% (N=97) were categorized with overvaluation and 32% (N=45) as without clinical overvaluation. Table 2 summarizes the demographic and psychiatric characteristics of the groups with and without overvaluation and the statistical tests. Consistent with the dimensional analyses above, the two groups did not differ significantly in age, gender, or ethnicity/race. In terms of psychiatric co-morbidity, the two groups did not differ significantly in lifetime (i.e., lifetime/current versus never) rates of mood or substance use disorders but the overvaluation group had significantly higher lifetime rates of anxiety disorders.

Table 2.

Demographic and psychiatric characteristics of Overvaluation (n = 97) and without Clinical Overvaluation (n = 45) Groups

| Clinical Overvaluation (N = 97) | Without Clinical Overvaluation (N = 45) | Test Statistica | p value | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.5 (11.0) | 43.7 (12.1) | F(1, N=142) = 0.01 | 0.92 | .000 |

| Female, N (%) | 72 (74.2%) | 33 (73.3%) | χ2 (1, N=142)=0.01 | 0.91 | .009 |

| Ethnicity, N (%)a | χ2 (1, N=142)=1.47 | 0.23 | .102 | ||

| Caucasian | 45 (46.4%) | 16 (35.6%) | χ2 (2, N=142)=1.51 | 0.47 | .103 |

| African-American | 33 (34.0%) | 19 (42.2%) | χ2 (3, N=142)=1.72 | 0.63 | .110 |

| Hispanic-American | 13 (13.4%) | 6 (13.3%) | |||

| “Other”/non-Caucasian | 6 (6.2%) | 4 (8.9%) | |||

| DSM-IV diagnoses, lifetime, No (%) | |||||

| Mood disorders | 51 (52.6%) | 18 (40.0%) | χ2 (1, N=142)=1.95 | 0.16 | .117 |

| Anxiety disorders | 46 (47.4%) | 12 (26.7%) | χ2 (1, N=142)=5.48 | 0.02 | .196 |

| Substance use disorders | 21 (21.6%) | 10 (22.2%) | χ2 (1, N=142)=0.01 | 0.94 | .010 |

| Age at BED Onset, mean (SD) | 25.8 (12.3) | 24.7 (12.7) | F(1, N=142) = 0.25 | 0.62 | .000 |

Note: Test statistic = chi-square for categorical variables and analyses of variance (F values) for dimensional variables. p values are for two-tailed tests. For ethnicity analyses, chi-square tests are shown for Caucasian versus non-Caucasian groups (df=1), Caucasian versus African-American versus Hispanic/American/Other groups (df=2); and for Caucasian versus African-American versus Hispanic-American versus Other groups (df=3). Effect size measures are phi coefficients for categorical variables and partial eta-squared for dimensional variables.

Categorical Analyses: Clinical Demographic and Psychiatric Characteristics of Overvaluation

Table 3 summarizes descriptive statistics and findings from ANOVAs, including effect size measures (Partial η2), comparing the overvaluation groups on the clinical study measures. The groups did not differ significantly in BMI, binge-eating frequency, or EDE restraint scores. The clinical overvaluation group reported significantly (p < 0.001) greater levels of eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE eating-, shape-, and weight-concern scales) and negative affect, and significantly lower self-esteem. Because the two groups differed significantly in the proportion with anxiety disorder co-morbidity (i.e., the overvaluation group had significantly higher rates of lifetime anxiety disorders), we performed a series of ANCOVAs controlling for anxiety disorder co-morbidity for all of the clinical measures. In no instances did controlling for anxiety disorder co-morbidity alter any of the findings regarding group differences (i.e., all the significant findings remained significant). Table 3 includes Partial η2 values for the ANCOVAs and it is evident that controlling for anxiety disorder co-morbidity did not attenuate the size of the group differences. We also performed two additional series of ANCOVAs controlling for mood disorders and for all psychiatric co-morbidity, respectively, and the pattern of findings and effect sizes remained essentially unchanged (data not shown).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and ANOVAs Comparing the Overvaluation (n = 97) and without Clinical Overvaluation (n = 45) Groups on Clinical Measures

| Measure | Clinical Overvaluation | Without Clinical Overvaluation | F | Partial η2 | Partial η2(ANCOVA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Eating Disorder Examination | |||||||

| Shape Concerna | 3.79 | 1.16 | 2.54 | 1.11 | 37.12*** | .21 | .18 |

| Weight Concerna | 3.29 | 1.11 | 2.54 | 0.84 | 16.15*** | .10 | .08 |

| Restraint | 1.74 | 1.37 | 1.44 | 1.26 | 1.55 | .01 | .00 |

| Eating Concern | 2.05 | 1.25 | 1.30 | 1.09 | 12.03*** | .08 | .06 |

| Weekly (OBE) Binge Eating | 4.41 | 3.20 | 5.09 | 5.32 | 0.89 | .01 | .01 |

| Weekly SBE Frequency | 2.93 | 3.76 | 2.70 | 3.61 | 0.22 | .00 | .00 |

| Body Mass Index | 37.95 | 5.13 | 39.56 | 6.08 | 2.65 | .02 | .02 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 17.39 | 9.83 | 9.39 | 7.41 | 22.79*** | .15 | .12 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 27.99 | 6.45 | 32.83 | 5.54 | 18.18*** | .12 | .10 |

The EDE Shape Concern and Weight Concern scale scores were calculated without their respective overvaluation items included in the interview’s standard scoring methods. If the overvaluation items were included, the means and standard deviations of these scales would be as follows: 3.93 ± 1.05 (Shape Concern) and 3.53 ± 0.99 (Weight Concern) for the clinical overvaluation group and 2.35 ± 0.98 (Shape Concern) and 2.26 ± 0.74 (Weight Concern) for the subclinical overvaluation group. Note: OBE = objective bulimic episodes; SBE = subjective bulimic episodes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Partial η2 is an effect size measure (cutoff conventions are .01–.09 for small effects and .10–.24 for medium effects). ANCOVA was performed to control for group differences in co-morbidity with anxiety disorders.

Discussion

The present study examined the significance of overvaluation of shape/weight for the diagnosis of BED in ethnically diverse (57% non-Caucasian) obese patients with BED seeking treatment for overweight and binge-eating in primary care. Overall, 68% of the participants with BED were categorized with clinical overvaluation, a figure that is comparable to that reported for a primarily (82%) Caucasian patient group with BED assessed at a specialty research clinic (Hrabosky et al., 2007). Participants with overvaluation did not differ significantly in ethnicity/race or other demographic features (age and gender) from participants who do not overvalue their shape/weight. Overvaluation – both categorically and dimensionally - was not associated with either BMI or with binge-eating frequency. However, overvaluation was associated with significantly greater levels of eating-disorder psychopathology and poorer psychological functioning (higher depression and lower self-esteem levels). These findings, which are consistent with those from both specialty research clinics (Grilo, Crosby et al., 2009; Hrabosky et al., 2007) and community samples (Goldschmidt et al., 2001; Grilo et al., 2010) that overvaluation of shape/weight reflects an important distinguishing clinical feature within BED. We also found that overvaluation was associated with greater frequency of co-morbidity with anxiety disorders. Importantly, however, the significant group differences in clinical measures (i.e., across eating-disorder, depression, and self-esteem domains) by overvaluation status persisted even after controlling for group differences in rates of co-morbidity with anxiety disorders (and also after controlling for other forms of psychiatric co-morbidity such as mood disorders). Collectively, these findings suggest that overvaluation does not simply reflect concern commensurate with being obese or with frequency of binge-eating, but is strongly associated with heightened eating-related psychopathology and psychological distress even after controlling for anxiety disorder (and other psychiatric disorder) co-morbidity, and therefore warrants consideration as a diagnostic specifier for BED as it appears to identify a more disturbed variant of BED.

The construct of overvaluation of shape/weight has diagnostic and clinical relevance. For bulimia nervosa, overvaluation is a required criterion, and studies have documented its nearly universal presence in clinical samples (Grilo, Crosby et al., 2009). For BED, our findings suggest that overvaluation may convey more clinically-relevant and nuanced information to clinicians and researchers by simply using a specifier. The advantages of adding specifiers to the DSM system in general have been cogently addressed (Brown & Barlow, 2005) and have traditionally been used for some diagnostic categories such as, for example, with mood disorders to convey severity or presence of important clinical features. Similarly, in the case of eating disorders, the DSM has used “subtypes” to convey important clinical features about anorexia nervosa (i.e., restricting subtype versus binge-purge subtype) and bulimia nervosa (i.e., purging type versus non-purging type). In the case of BED, the presence or degree of overvaluation conveys important information regarding individual differences, not just in the disorder severity - i.e., our findings here indicate that overvaluation does not merely reflect concerns commensurate with extent of excess weight or binge-eating frequency. Indeed, overvaluation in BED conveys information about a clinically significant cognitive feature as suggested by strong associations with heightened eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE scales, even after removing overvaluation from the scoring) and diverse psychological functioning measures (BDI and RSE) even after covarying for the effects of psychiatric co-morbidity. Adding overvaluation as a specific to the BED diagnosis would parallel, in part, the nosological structure of the other eating disorder diagnoses which include and require specific cognitive aspects of body image, not just disordered eating and weight control behaviors. Two recent studies have reported that overvaluation of shape/weight has prognostic significance in studies of primarily Caucasian patients treated in specialty clinics. One study (Masheb & Grilo, 2008) reported that pretreatment levels of overvaluation of shape/weight significantly predicted worse post-treatment outcomes in a trial testing guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss treatments. A second study (Grilo, Masheb, & Crosby, in press) reported that overvaluation of shape/weight predicted and moderated cognitive behavioral therapy and medication outcomes for BED. Thus, the presence of this cognitive feature could also signal to clinicians that a patient may have a more disturbed variant of BED and perhaps consider more intensive clinical interventions and greater focus on body image.

Strengths of this study include the recruitment of an ethnically diverse (57% non-Caucasian) obese patient group with BED from primary care settings assessed reliably by doctoral research clinicians using state-of-the-art measures. Nearly all of the literature pertaining to clinical samples of BED comes from specialty research clinics and the generalizability of those studies to general clinical settings may be limited or confounded by biases (Fairburn et al., 1996). Some studies have found that those “clinic biases” may be even greater for minority groups (Grilo et al., 2005; Pike et al., 2001). Indeed, in sharp contrast to recent epidemiological findings that binge-eating occurs among African-American and Hispanic-American groups at comparable or higher rates than Caucasians (Algeria et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2011), inspection of the ethnic/racial composition of most study groups from specialty clinics reveals substantially lower rates of minority group members than expected (Franko et al., in press). Marques et al (2011) reported that ethnic minority groups with disordered eating had lower rates of mental health service utilization than Caucasian groups. Thus, our recruitment method in primary care resulted in a clinically-relevant and ethnically diverse study group and allowed for meaningful analyses which revealed that that Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic-American groups with BED did not differ significantly in either dimensional levels of overvaluation or proportion categorized with overvaluation.

Several potential limitations are noteworthy. Participants were respondents to recruitment flyers placed in primary care centers advertising a treatment study for overweight persons who binge-eat. Findings may not generalize to obese BED patients in primary care who do not choose to seek treatment for eating/weight issues or who are uninterested or unwilling to participate in research studies, or to persons with BED who are not overweight. Although we adopted relatively few exclusionary criteria (notably current antidepressant therapy, selected severe psychiatric conditions - such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and current substance use dependence, cardiac and liver disease, and uncontrolled hypertension, thyroid disease, or diabetes), our findings may not generalize to obese patient groups with different clinical characteristics. It is possible, for example, that obese persons with more severe medical co-morbidities might differ in the nature of their weight/shape concerns and/or have different priorities regarding health and appearance. Moreover, given our exclusion of participants currently taking antidepressant medications, it is possible that our observed rates of psychiatric co-morbidities might differ from those for such patients. Our cross-sectional analysis here precludes any statements regarding the prognostic significance of this construct in BED and further research should examine its utility as a predictor/moderator of treatment outcomes in diverse patient groups to build upon recent findings regarding short term outcomes (Masheb & Grilo, 2008; Grilo et al., in press)..

Highlights.

Overvaluation of shape/weight is considered a core feature across eating disorders.

Overvaluation is associated with greater eating psychopathology and psychological problems

Overvaluation warrants consideration as a diagnostic specifier for BED in DSM-5.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK073542). Dr. Grilo was also supported by National Institutes of Health grant K24 DK070052.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahrberg M, Trojca D, Nasrawi N, Vocks S. Body image disturbance in binge eating disorder: a review. European Eating Disorders Review. doi: 10.1002/erv.1100. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng XL, Striegel-Moore RH. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(suppl):S15–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for revised Beck Depression Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: 25 years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Dimensional versus categorical classification of mental disorders in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and beyond: comment on special series. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:551–556. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Levine AS, Thuras P, Mitchell JE. A survey of binge eating and obesity treatment practices among primary care providers. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:348–353. doi: 10.1002/eat.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Norman PA, O’Connor ME, Doll H. Bias and bulimia nervosa: how typical or clinic cases? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:386–391. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient-Version (SCID-I/P) New York: NYSPI; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Thompson-Brenner H, Thompson DR, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in adults in randomized clinical trials of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0026700. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Hilbert A, Manwaring JL, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Fairburen CG, Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH. The significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2010;48:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith RA, Beumont EG, Russell J, Schotte D, Thornton C, Touyz SW, Varano P. Measuring self-esteem in dieting disordered patients: the validity of the Rosenberg and Coopersmith contrasted. Eating Disorders. 1999;25:227–231. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199903)25:2<227::aid-eat13>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Masheb RM, White MA, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Crow SJ, Mitchell JE. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and sub-threshold bulimia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Masheb RM, White MA, Crow SJ, Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE. Factor structure of the eating disorder examination interview in patients with binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2010;18:977–981. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Hrabosky JI, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, Masheb RM. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder and overweight controls: refinement of a diagnostic construct. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:414–419. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Lozano C, Elder KA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Spanish-language version of the Eating Disorder Examination interview. Journal Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11:231–240. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Lozano C, Masheb RM. Ethnicity and sampling bias in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:257–262. doi: 10.1002/eat.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Crosby RD. Predictors and moderators of response to cognitive behavioral therapy and medication for the treatment of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0027001. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA. Significance of overvaluation of shape/weight in binge-eating disorder: comparative study with overweight and bulimia nervosa. Obesity. 2010;18:499–504. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001a;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obesity Research. 2001b;9:418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Subtyping binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001c;69:1066–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, White MA. A controlled evaluation of the distress criterion for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:509–514. doi: 10.1037/a0024259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabosky JI, Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo CM. Overvaluation of shape and weight in BED. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:175–180. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the NCS Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1455–66. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen CN, Fang A, Chosak A, Diniz JB. Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:412–420. doi: 10.1002/eat.20787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Binge eating disorder: A need for additional diagnostic criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41:159–162. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. The nature of body image disturbance in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorder. 2003;33:333–341. doi: 10.1002/eat.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Prognostic significance of two sub-categorization methods for binge eating disorder: negative affect and overvaluation predict, but do not moderate, specific outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Recurrent binge eating with and without the “undue influence of weight or shape on self-evaluation”: Implications for the diagnosis of binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:929–938. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Myers TC, Crosby RD, Hay PJ, Mitchell JE. Bulimic eating disorders in primary care: hidden mortality still? Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2010;17:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KM, Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG. A comparison of black and white women with binge eating disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1455–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL. Should binge eating disorder be included in the DSM-V? A critical review of the state of the evidence. Annual Review Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:305–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TD, Zhu G, Martin NG. Undue influence of weight and shape: is it distinct from body dissatisfaction and concern about weight and shape? Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:819–828. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96:465–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH, Fairburn CG. Bias in binge eating disorder: how representative are recruited clinic samples? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:383–388. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]