Abstract

The intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus (AF) is subjected to high circumferential tensile stresses resulting from nucleus pulposus pressurization under axial compression. In other pressure containing tissues, such as blood vessel walls, residual compressive stresses along the inside surface of the tissues without pressurization reduce peak tensile stresses under pressurization. This study hypothesized that similar patterns of residual stress exist in the annulus fibrosus. Accurate characterization of residual stresses is essential for both the incorporation of nonlinear material descriptions into models of the disc as well as the design of effective annulus repair strategies. By imaging nine bovine caudal discs before and after the release of residual stresses via incision, we measured a mean residual stretch of 0.86±0.13 at the inner AF and 1.02±0.08 at the outer AF. These stretch values were used to calculate a gradient of residual stress ranging from −230±22 kPa of compression at the inner AF to 54±0.2 kPa of tension at the outer AF. Material models of AF have assumed that the AF was in a stress free reference state when there are no external loads. However, this study documents that there are large residual stresses in the AF even without external loads. The release of residual tension in the outer AF by herniation, needle injection or incisions makes closure difficult and may accelerate degeneration of the surrounding tissue. Retention of these residual stresses may be essential to maintaining disc mechanical function and to producing viable AF repair techniques.

Keywords: residual stress, opening angle, image analysis, point tracking

Introduction

The intervertebral disc (IVD) annulus fibrosus (AF) serves the dual roles of providing flexible connectivity between adjacent vertebral bodies and containing both osmotic and load induced pressurization in the nucleus pulposus (NP). Under axial compression of the spinal column, the fluid rich nucleus pulposus generates hydrostatic pressure up to 2.5 times the applied stress (Nachemson and Morris 1964; Wilke et al. 1999). Failure of the AF to contain this pressure effectively may lead to pathologies such as herniation or sciatic nerve impingement. Proper function of the healthy AF, therefore depends on its ability to contain large internal pressures.

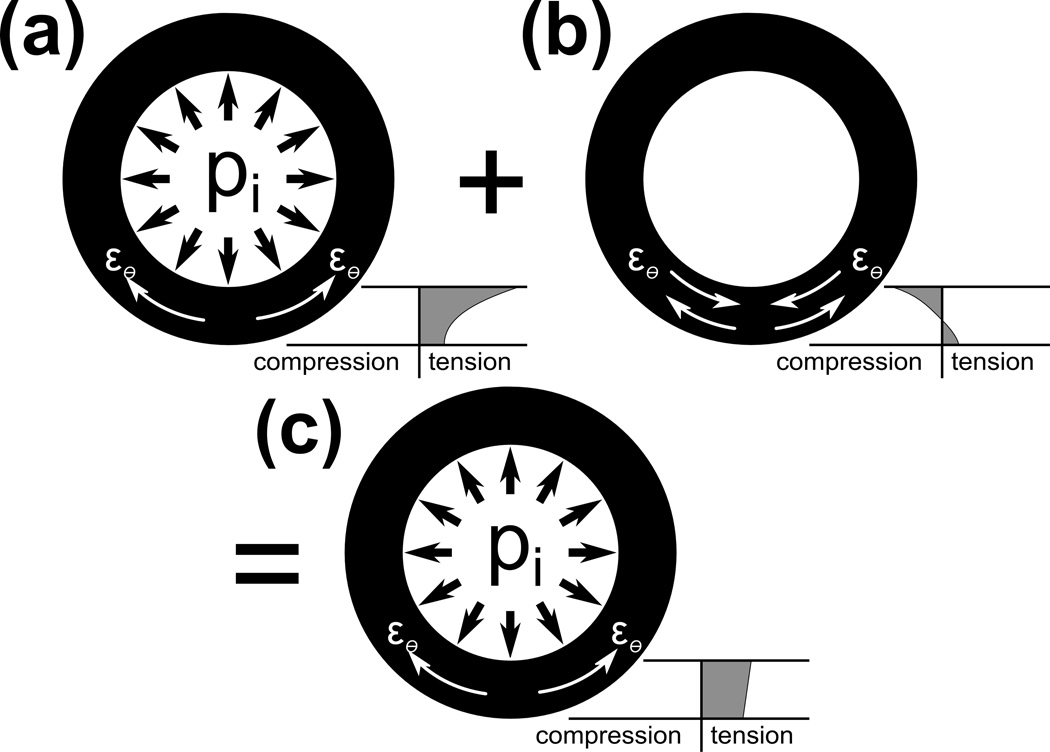

Similar fluid pressure containing behavior has been extensively studied in blood vessels and the heart (Chuong and Fung 1986; Fung and Liu 1995; Rachev and Greenwald 2003). In the unpressurized state, the walls of blood vessels exhibit a distribution of residual circumferential stress throughout their thickness ranging from compression at the inner wall to tension at the outer wall. Under pressurization, these residual stresses act to minimize the peak circumferential tensile stress in the vessel wall (Figure 1) (Delfino et al. 1997). Despite containing higher pressures, the distribution of residual circumferential stress in the AF has not yet been investigated.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a thick walled vessel under internal pressure, pi. (a) Distribution of circumferential strains, εθ, under internal pressure without residual strains present results in tensile circumferential strains throughout the wall with peak tensile strains on the inside surface. (b) Residual circumferential strains with the outer portion of the wall under tension and in equilibrium with the inner portion of the wall under compression can be added to the system. (c) Resultant pressurized vessel with residual strains provides a more uniform tensile circumferential strain radially that effectively decreases peak tensile strain under pressure compared to (a), thereby reducing the potential for tensile failure under loading.

A more complete understanding of the residual stresses in the AF is necessary for several reasons. Investigations into the structure and function of the intervertebral discs are being performed with finite element models using increasingly sophisticated nonlinear hyperelastic (Natarajan et al. 2004; Natarajan et al. 2006; Little et al. 2007; Hollingsworth and Wagner 2011; Massey et al. 2011) and porohyperelastic (Hsieh et al. 2005; Schroeder et al. 2010) material models. In order for these material models to accurately describe the behavior of an intact motion segment, the initial stress state of the disc in the unloaded configuration must be known. Additionally, effective repair of the AF following NP removal or replacement requires returning the tissue to a stress state as close to that of the healthy condition as possible (Wilke et al. 2006). Finally, degenerative changes that alter residual stress in the disc may increase susceptibility to pathology related to excessive radial bulging of the AF under compressive load. For these reasons, measuring the residual stress state of the AF is a priority and notable omission in the literature.

We hypothesized that the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus is under significant residual circumferential strain in the unloaded state, which we have defined as the absence of both external loads and internal swelling loads. This hypothesis was tested by photographing bovine caudal intervertebral discs before and after release of residual strain by an initial full thickness radial scalpel incision and the incision followed by NP removal. These two states are intended to measure strain released by an acute tear or scalpel incision, which is necessary for designing AF suture or repair techniques, and the radial distribution of residual strain, which is necessary for both computational modeling and designing tissue engineered disc structures. Digital image analysis was utilized to estimate residual strains using methods established for homogeneous thick walled vessels and to directly measure stretch and changes in curvature using fiduciary markers.

Methods

Intervertebral discs (n=9) were harvested from caudal levels c2–3 to c5–6 of skeletally mature steer tails obtained from a local abattoir. Following the removal of surrounding tissue, the discs were separated from the vertebrae with a scalpel, with care taken to ensure an even disc thickness. While the radial constraint at the disc-vertebrae boundaries will influence how the disc will respond to applied loads, in the unloaded state the bovine IVD did not display a visible radial bulge, confirming the lack of internal pressure of the disc, and likewise the radial constraint imposed by the endplates, in the absence of axial load was assumed to be negligible. Removal of the discs from the adjacent vertebrae, therefore, allowed calculation of residual strains resulting purely from the formation of extracellular matrix, and not from strains arising from external loads or internal swelling. The discs were then wrapped tightly in aluminum foil and frozen at −20 °C until testing. Prior to testing, the discs were thawed to room temperature and India ink was used to apply a series of marking dots to the AF near the outer periphery (Figure 2). The disc was then placed in a beaker with (10mL) phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS), which was determined to be the minimum volume required for complete immersion. A photograph of the disc was taken using a digital camera (Canon 300D, Canon USA) affixed to a ring stand above the beaker. Following the initial photograph (Figure 2a), the disc was removed from the saline and incised radially with a scalpel, through its full height, from the center of the NP through the outer AF and photographed again (Figure 2b). Caudal discs are nearly axially symmetric (O'Connell et al. 2007) and the anatomical location of the incision (i.e. anterior, posterior, or lateral) was randomly selected for each disc. Finally, the NP was excised from the disc, and it was photographed a third time (Figure 2c). Over the course of the experiment, the disc spent less than five minutes immersed in saline. A pilot study, in which a disc was left in saline for six hours following NP excision and photographed at thirty minute intervals, confirmed that opening resulting from differential swelling of the inner and outer AF occurs at a much longer time scale (τ=251 min.) relative to the time required for this experiment (Figure 3).

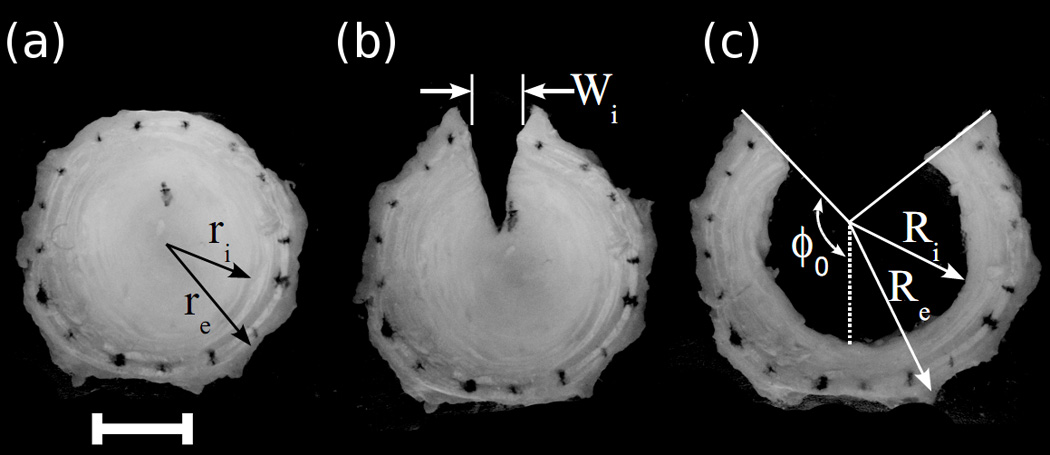

Figure 2.

Representative photographs of a disc in the intact state (a), following radial incision (b), and following radial incision and NP removal (c). Residual strains were calculated from both manual measurement of changes in disc geometry and from relative displacements of ink markings.

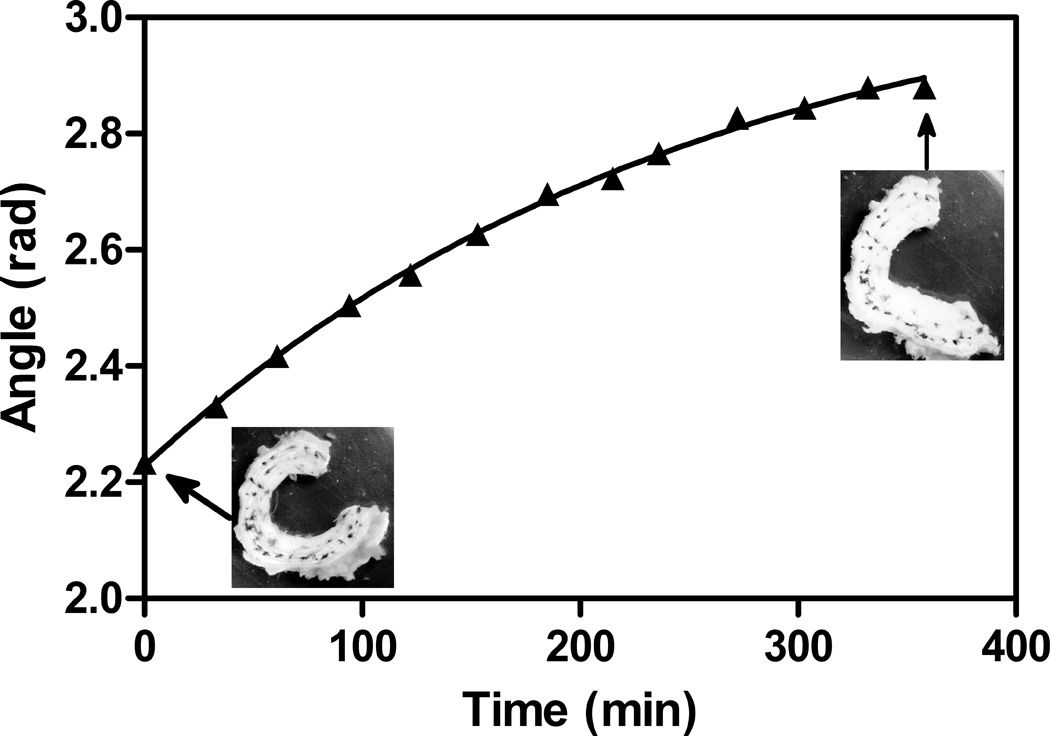

Figure 3.

A pilot study indicated that while immersion in saline causes an increase in opening angle because of differential swelling of the inner AF relative to the outer AF, this phenomenon occurs at a time scale much longer than that required to make residual stress measurements. The solid line indicates a single phase decay fit with a time constant of 251 minutes.

Two different analyses were performed on the disc photographs in order to calculate residual tissue strains. The first analysis consisted of digitizing the three images using ImageJ in order to measure outer AF opening, Wi, resulting from the first incision (Figure 2b). Additionally, the total residual hoop strain relieved by NP removal was calculated using the method presented by Chuong and Fung (Chuong and Fung 1986). Two lines were manually drawn onto the image tangential to the cut surfaces of the AF (Figure 2c). Inner and outer radii were measured from the intersection point of these lines at two different locations and averaged. Opening angle was defined as one half of the reflex angle between the two lines. Circumferential residual stretch throughout the thickness of the AF was then calculated from:

| (1) |

Where r is the radial coordinate (from ri to ro) through the thickness of the annulus in the intact state and R is the radial coordinate (from Ri to Ro) in the strain relieved state. The opening angle, ϕ0, arises from a change in residual strain from inner to outer annulus. In order to account for interspecimen variability, radial coordinates were normalized to the outside radius. This analysis results in an average stretch ratio around the circumference of the disc, which assumes that all residual strain was relieved by the radial incision and NP removal.

The second method utilized point tracking to calculate the local stretch and changes in curvature between states. A custom written Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) code was used to track the relative positions of the ink dots at the outer periphery of the AF. The dots were digitized manually and automatically fine tuned by locating the centroids of the marker points. The distance between adjacent pairs of dots was then compared between incised and intact states and between NP removed and intact states to calculate local circumferential stretch. Additionally, each set of three adjacent points was used to calculate a local radius of curvature. Variations in specimen size and in the precision of ink dot placement resulted in high variability in calculated radius of curvature. Each local value, calculated in both incised and NP removed, was normalized to its intact value for comparison. Average circumferential stretch and relative radius of curvature were compared between states using a paired t-test with p<0.05 indicating significance. Circumferential stretch values for the outer periphery of the AF obtained by the two different methods were compared using an un-paired t-test. Approximate residual stress values were then calculated assuming a compressive modulus of 110 kPa (Umehara et al. 1996) and a tensile modulus of 2.52 MPa (Acaroglu et al. 1995; Elliott and Setton 2001). It is important to note that these effective moduli assume a homogeneous material, and likely lead to underestimated stresses in individual collagen fibers.

Results

Upon initial incision, the outer AF opened by an average of 4.3±1.8 mm. Following removal of the NP, the average opening angle ϕ0 was 135±2.2°, resulting in a circumferential stretch ratio, λθ, of 0.86±0.13 in the inner AF and 1.02±0.08 in the outer AF (Figure 4). Local stretch and curvature, as calculated from ink dot displacement, did not show any consistent trends with angular position relative to the incision site, though in some specimens the radius of curvature increased near the incision site following both incision and NP removal. Average circumferential stretch around the AF was 1.02±0.086 following incision and 1.05±0.11 following NP removal (Figure 5). Only NP removal had a significant effect. The average radius of curvature around the AF increased by a factor of 1.16±0.54 following incision and 1.34±0.65 following NP removal, which was significant in both cases. The circumferential stretch ratio at the outer periphery of the AF was not significantly different between the two methods (p=0.7). The stretch values measured using the opening angle method correspond to mean Green strains of −13% and 2% respectively. These residual stretch values result in approximate values for residual stresses of compressive stress in the inner AF of 230±22 kPa and a tensile stress in the outer AF of 54±0.2 kPa.

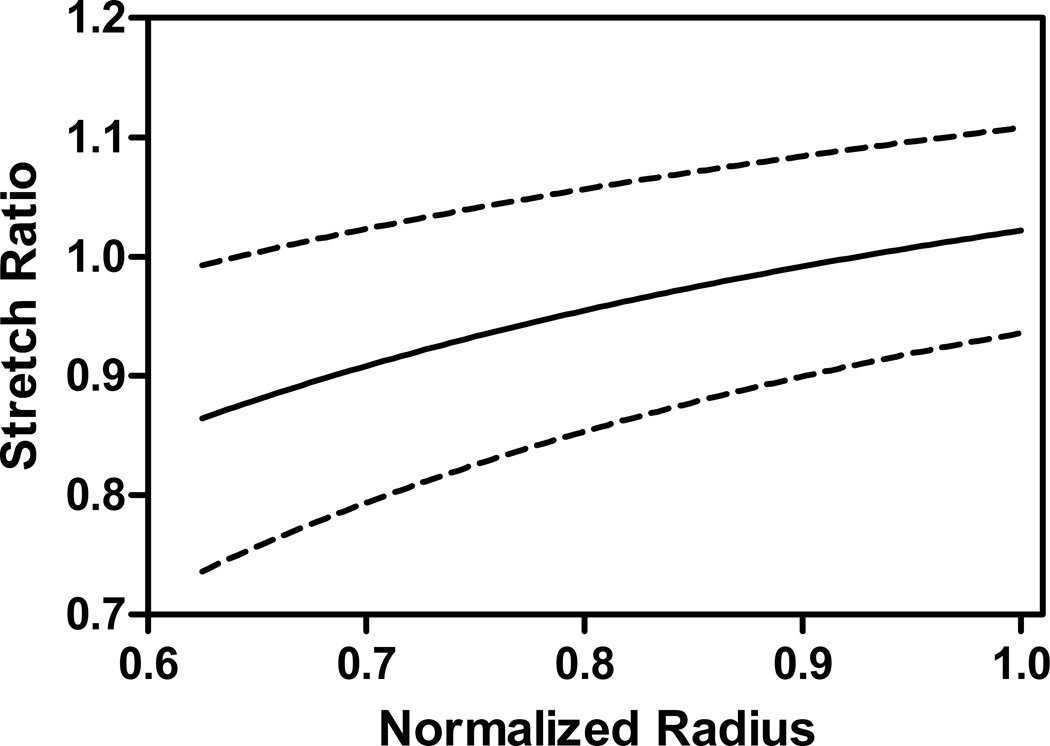

Figure 4.

Mean residual stretch (line) ±SD (dotted line) as measured using the opening angle method. Residual stretch varied from compression at the inner surface of the AF to tension at the outer surface.

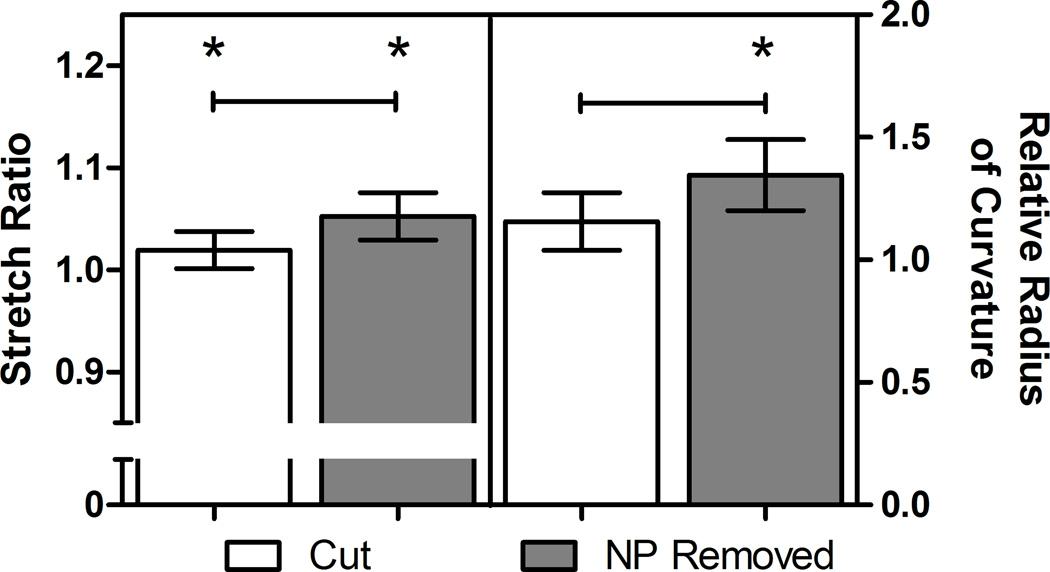

Figure 5.

Average (±95% Confidence Interval) local stretch ratio (left) and local radius of curvature (right) of the discs as measured with point tracking. Values are presented for radial incision and radial incision with NP removal groups relative to intact. Bars indicate significant difference between groups (p=0.0008 for local stretch ratio and p=0.0128 for local radius of curvature), and * indicates significant difference from one (p=0.028 and p< 0.00001 for local stretch ratio and, p = 0.165 and p< 0.00001 for local radius of curvature with initially cut and with NP removal respectively).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative investigation of residual circumferential strain in the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus. These results demonstrate residual tensile strains exist at the outer periphery which becomes large residual compressive strains at the inner periphery of the AF. Our results show that the distribution of residual stretch in the AF is similar to that of other pressure containing organs. The mean compressive circumferential stretch ratio for the inner AF is similar to stretch ratios in the inner walls of arteries (Chuong and Fung 1986). It is therefore likely that theses stresses serve a similar purpose of reducing peak circumferential tensile stresses under axial compression of the disc.

Prior research has assumed that a disc with no external load is in a stress free state, though these measurements demonstrate that even in the absence of both axial load (or other muscle loading) on the disc and internal pressurization, there are large circumferential residual strains in the AF. The residual compressive strain may serve to reduce tensile stress on the inner AF from internal pressurization resulting in more uniform stress through the AF. Thus, the AF is able to make more efficient use of the tension bearing collagen fibers throughout its entire thickness. Additionally, residual stresses may reduce interlamellar shear loads by reducing the gradient of circumferential stress.

While it is not known how these residual stresses arise, developmental studies have shown that the basic lamellar structure of the AF is established quite early in embryogenesis and then remains mostly unchanged (Hayes et al. 1999). The disc then grows radially through thickening of the lamellae as cells deposit more matrix (Peacock 1951; Peacock 1952). As the disc continues to grow, extracellular matrix synthesis is greater in the NP and inner AF than the outer AF (Antoniou et al. 1996). This pattern of growth is consistent with formation of residual compression at the transition between the AF and NP and residual tension at the outer periphery of the AF. Another possible mechanism for residual stresses formation is the distribution of proteoglycans through the AF. The amount of curling in articular cartilage (Setton et al. 1998; Narmoneva et al. 1999) depends on the osmolarity of the bathing solution. The distribution of proteoglycans through the aorta has been proposed as a mechanism for residual stresses in the aorta (Azeloglu et al. 2008). Iatridis et al. have measured a steep decrease in proteoglycans concentration at the outer AF (Iatridis et al. 2007). This gradient might also be a factor in the formation of residual stresses in the AF. Loss of proteoglycans with degeneration, therefore, could cause a loss of such beneficial residual stresses.

Both of the methods used in this study are limited by some technical and theoretical assumptions. The opening angle method assumes that in the stress relieved (ie. NP removed) state retains a constant curvature. While this assumption was generally true for caudal discs and upheld by our results, the observation of some increase in radius of curvature close to the incision site suggests that Equation 1 may not fully describe residual strains in the lamellar structure of the AF. This assumption also limits application of this method to human lumbar discs. The point tracking technique is limited by the inability to place tracking points exactly on the outer edge of the AF. It is also not practical to place marks on the inner edge of the AF prior to NP removal, because it is the removal of the NP that defines that inner edge. Despite these limitations, the estimates of residual stretch at the outer AF made by the two methods were not significantly different, suggesting that the above assumptions have small effects. Our calculations of residual stress are limited by the assumption of a homogeneous continuum. The stresses calculated are average estimates that demonstrate that they are large enough to have a relevant impact on stress calculations in the AF, although future studies using more accurate constitutive models could account for radial variations or the elaborate fiber-reinforced nature of the AF.

This study was conducted using bovine intervertebral discs due to their low interspecimen variability, and approximately axisymmetric geometry. Despite differences in size, shape, and material properties between human and bovine discs, and between lumbar and caudal regions, their resting compressive stresses in vivo are similar (Oshima et al. 1993; Demers et al. 2004; MacLean et al. 2005). We therefore expect that the residual compressive stresses in the two species will be similar. Human discs were also avoided in this first study because spatial mapping of residual stresses in human IVDs will most likely show some variation in residual stress around the periphery of the AF as well as exhibiting changes with age and disease.

Hyperelastic and other nonlinear material models of AF have assumed that the AF has a stress free reference state when there are no external loads. However, there are large residual strains in the AF even without external loads. These residual strains are comparable in magnitude to surface strains imposed by axial compression (Heuer et al. 2008). Residual stresses must be accounted for in simulations of AF and IVD for accurate stress estimates. This study documents the presence of large residual strains in the AF even in the absence of NP pressurization using two measurement techniques. Residual stresses in the AF are important for maintenance of mechanical function to reduce peak tensile stresses under load. The release of AF residual stresses from injury or herniation will alter the stress state and may accelerate damage accumulation in the IVD.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH grants R0 AR0511461, R01 AR057397 and T32 HL007944, and the McClure Musculoskeletal Research Center of the University of Vermont. Dr. Jeffrey Weiss of the University of Utah engaged in helpful discussions about residual stress.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to disclose

References

- Acaroglu ER, Iatridis JC, Setton LA, Foster RJ, Mow VC, Weidenbaum M. Degeneration and aging affect the tensile behavior of human lumbar anulus fibrosus. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:2690–2701. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou J, Steffen T, Nelson F, Winterbottom N, Hollander AP, Poole RA, Aebi M, Alini M. The human lumbar intervertebral disc: evidence for changes in the biosynthesis and denaturation of the extracellular matrix with growth, maturation, ageing, and degeneration. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:996–1003. doi: 10.1172/JCI118884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeloglu EU, Albro MB, Thimmappa VA, Ateshian GA, Costa KD. Heterogeneous transmural proteoglycan distribution provides a mechanism for regulating residual stresses in the aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1197–H1205. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01027.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CJ, Fung YC. On residual stresses in arteries. J Biomech Eng. 1986;108:189–192. doi: 10.1115/1.3138600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino A, Stergiopulos N, Moore JE, Jr, Meister JJ. Residual strain effects on the stress field in a thick wall finite element model of the human carotid bifurcation. J Biomech. 1997;30:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers CN, Antoniou J, Mwale F. Value and limitations of using the bovine tail as a model for the human lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:2793–2799. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000147744.74215.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Setton LA. Anisotropic and inhomogeneous tensile behavior of the human anulus fibrosus: experimental measurement and material model predictions. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:256–263. doi: 10.1115/1.1374202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung YC, Liu SQ. Determination of the mechanical properties of the different layers of blood vessels in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2169–2173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AJ, Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. Role of actin stress fibres in the development of the intervertebral disc: cytoskeletal control of extracellular matrix assembly. Dev Dyn. 1999;215:179–189. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199907)215:3<179::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer F, Schmidt H, Wilke HJ. The relation between intervertebral disc bulging and annular fiber associated strains for simple and complex loading. J Biomech. 2008;41:1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth NT, Wagner DR. Modeling shear behavior of the annulus fibrosus. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:1103–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh AH, Wagner DR, Cheng LY, Lotz JC. Dependence of mechanical behavior of the murine tail disc on regional material properties: a parametric finite element study. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:1158–1167. doi: 10.1115/1.2073467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis JC, MacLean JJ, O'Brien M, Stokes IA. Measurements of proteoglycan and water content distribution in human lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1493–1497. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dd3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JP, Adam CJ, Evans JH, Pettet GJ, Pearcy MJ. Nonlinear finite element analysis of anular lesions in the L4/5 intervertebral disc. J Biomech. 2007;40:2744–2751. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean JJ, Lee CR, Alini M, Iatridis JC. The effects of short-term load duration on anabolic and catabolic gene expression in the rat tail intervertebral disc. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey CJ, van Donkelaar CC, Vresilovic E, Zavaliangos A, Marcolongo M. Effects of aging and degeneration on the human intervertebral disc during the diurnal cycle: A finite element study. J Orthop Res. 2011;30:122–128. doi: 10.1002/jor.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachemson AL, Morris JM. In vivo measurements of intradiscal pressure. Discomoetry, a method for determination of pressure in the lower lumbar discs. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1964;46:1077–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narmoneva DA, Wang JY, Setton LA. Nonuniform swelling-induced residual strains in articular cartilage. J Biomech. 1999;32:401–408. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan RN, Williams JR, Andersson GB. Recent advances in analytical modeling of lumbar disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:2733–2741. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146471.59052.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan RN, Williams JR, Andersson GB. Modeling changes in intervertebral disc mechanics with degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 2):36–40. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell GD, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM. Comparison of animals used in disc research to human lumbar disc geometry. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:328–333. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000253961.40910.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H, Ishihara H, Urban JP, Tsuji H. The use of coccygeal discs to study intervertebral disc metabolism. J Orthop Res. 1993;11:332–338. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock A. Observations on the pre-natal development of the intervertebral disc in man. Journal of Anatomy. 1951;86:260–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock A. Observations on the postnatal structure of the intervertebral disc in man. Journal of Anatomy. 1952;86:162–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachev A, Greenwald SE. Residual strains in conduit arteries. J Biomech. 2003;36:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder Y, Huyghe JM, van Donkelaar CC, Ito K. A biochemical/biophysical 3D FE intervertebral disc model. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2010;9:641–650. doi: 10.1007/s10237-010-0203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setton LA, Tohyama H, Mow VC. Swelling and curling behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120:355–361. doi: 10.1115/1.2798002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umehara S, Tadano S, Abumi K, Katagiri K, Kaneda K, Ukai T. Effects of degeneration on the elastic modulus distribution in the lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976. 1996;21:811–819. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199604010-00007. discussion 820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke HJ, Neef P, Caimi M, Hoogland T, Claes LE. New in vivo measurements of pressures in the intervertebral disc in daily life. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:755–762. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke HJ, Rohlmann F, Neidlinger-Wilke C, Werner K, Claes L, Kettler A. Validity and interobserver agreement of a new radiographic grading system for intervertebral disc degeneration: Part I. Lumbar spine. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:720–730. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]