Abstract

Many extracellular and intrinsic factors regulate oligodendrocyte development, but their signaling pathways remain poorly understood. Although the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent pathway is implicated in oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) lineage progression, its molecular targets involved in myelinogenesis are mostly unidentified. We have analyzed mechanisms by which p38MAPK regulates oligodendrocyte development and demonstrate that p38MAPK inhibition prevents OPC lineage progression and inhibits MBP (myelin basic protein) promoter activity and Sox10 function. In white-matter tissue, differential levels of MAPK phosphorylation are observed in oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Phosphorylated p38MAPK was found in CC1- and CNP-expressing differentiated oligodendrocytes of the adult brain and was temporally associated with a decline in the levels of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in cells of this lineage. PDGF stimulates the phosphorylation of ERK, p38MAPK, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38MAPK inhibition was associated with increased ERK, JNK, and c-Jun phosphorylation. In the presence of PDGF, simultaneous inhibition of p38MAPK and either MAPK kinase (MEK) or JNK significantly alleviates the repression of myelin gene expression and lineage progression induced by p38MAPK inhibition alone. Dominant-negative c-Jun reverses the inhibition of myelin promoter activity by active MEK1 or dominant-negative p38MAPKα mutants, and phosphorylated c-Jun was detected at the MBP promoter after p38MAPK inhibition, indicating c-Jun as a negative mediator of p38MAPK action. Our findings indicate that p38MAPK activity in the brain supports myelin gene expression through distinct mechanisms via positive and negative regulatory targets. We show that oligodendrocyte differentiation involves p38-mediated Sox10 regulation and cross talk with parallel ERK and JNK pathways to repress c-Jun activity.

Introduction

Oligodendrocyte loss and demyelination are common pathological features of many white-matter and neurodegenerative disorders. The identification of signaling processes that promote or inhibit myelin formation by oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) is thus critical for therapeutic strategies. The effects of external stimuli, such as growth factors (Armstrong et al., 2002; Ness et al., 2004; Murtie et al., 2005), cytokines (Dell'Albani et al., 1998) and neurotransmitters (Gallo et al., 1996; Pende et al., 1997), on OPC proliferation and maturation are well characterized; however, less is known about intracellular kinase cascades that regulate myelin gene expression in developing OPCs.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) comprise families of Ser/Thr-specific kinases activated by extracellular stimuli through protein phosphorylation. Upstream MAPK kinases (MKKs/MEKs) phosphorylate MAPKs, which in turn phosphorylate a wide array of substrates. p38MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are stimulated by environmental stressors, whereas the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) family/p44/42 MAPK is associated with receptor tyrosine kinases and G-protein-coupled receptors. The stress-activated p38MAPK mediates signaling by proinflammatory stimuli (Freshney et al., 1994) and controls diverse processes such as cell growth and survival, depending on cellular context (Zetser et al., 1999; Juretic et al., 2001).

With the discovery of developmental functions for p38MAPK in various systems (Zhang et al., 2006; Hui et al., 2007; Ventura et al., 2007), it is becoming clearer that p38MAPK also regulates normal physiological processes. Recent evidence has indicated that p38MAPK is important for myelination in cultured Schwann cells (Fragoso et al., 2003) and OPCs (Fragoso et al., 2007). p38MAPK has been reported to affect both cell proliferation and lineage progression in the presence of growth factors (Baron et al., 2000) and to stimulate transient cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation (Bhat et al., 2007). However, the molecular mechanisms and signaling targets of p38MAPK, which in turn regulate OPC development and myelin gene expression, remain to be identified.

The role of ERK activation in oligodendrocytes has been linked with proliferation (Stariha and Kim, 2001a), process extension (Stariha et al., 1997), and cytokine-induced oligodendrocyte death (Horiuchi et al., 2006). Although both ERK and p38MAPK are known to regulate differentiation, antagonistic effects between these kinases have also been demonstrated in mitosis and tumorigenesis (Chao and Yang, 2001; Aguirre-Ghiso et al., 2003, 2004). Since the kinetics of ERK activation determines entry into programs of survival and/or differentiation (Colucci-DAmato et al., 2003), its role in neurodegenerative conditions may also involve a complex relationship with kinases such as p38MAPK.

In this study, we demonstrate that p38MAPK regulates OPC differentiation and myelin gene expression by modulating Sox gene function and by regulating parallel MAP kinase cascades, including JNK and ERK. We provide evidence that p38MAPK activity suppresses ERK phosphorylation and prevents the accumulation of phosphorylated c-Jun, an inhibitor of myelin gene expression. The simultaneous blockade of p38MAPK activity and c-Jun accumulation promotes myelin gene expression and lineage progression. Our study not only indicates that p38MAPK contributes to ERK, JNK, and c-Jun regulation but also reveals novel roles for MAPK cross talk in OPC development.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Cell culture medium (DMEM, HBSS), Lipofectamine 2000, Trizol reagent, SuperScript III reverse transcriptase, Platinum SuperTaq, and SYBR Green quantitative PCR (qPCR) detection kit were purchased from Invitrogen. N1 supplements, including insulin, selenium, transferrin, poly-d-ornithine, poly-d-lysine, triiodothyronine (T3), and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor (hPDGF-AB) was from Millipore. 4-[4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl]pyridine (SB203580), 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (SB202190), 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene (U0126), and anthra[1,9-cd]pyrazol-6(2H)-one (SP600125) were purchased from Calbiochem. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated biotinylated UTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay and luciferase assay kits were purchased from Promega, and the 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) kit was from R&D Systems. Control and p38α small interfering RNA (siRNA) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Oligonucleotide primers and probes were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. [γ-32P]ATP was purchased from PerkinElmer. All restriction enzymes, ligases, and T4 polynucleotide kinase were from New England Biolabs. RNAeasy RNA isolation kit and plasmid purification kits were purchased from QIAGEN. Antibody sources were as follows: BrdU from Dako, phospho-p38MAPK, p38MAPKα, p38MAPK, phospho-ATF2, phospho-ERK, ERK, phospho-JNK, JNK, c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun, and phospho-cdc2 (Tyr15) were purchased from Cell Signaling. SP1, phospho-c-Jun (for gel shifts), cdk2, p27 Cip/Kip, cyclin D1, and MKP-3 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. PDGFR-α, 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNP), and Sox10 were from Abcam; CC1, from Calbiochem; NeuN and actin, from Millipore; GFAP, from Sigma-Aldrich; and myelin basic protein (MBP), from Covance.

Tissue sections, immunohistochemistry, and confocal microscopy.

Freshly cut, floating sections of 30 and 40 μm thickness from postnatal day 4 (P4) to P44 mice were prepared on a sliding microtome as previously described (Yuan et al., 2002). Sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with blocking solution (10% goat serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.3% Triton X-100), and then rinsed in 1× PBS before incubation at 4°C for 48 h with primary antibodies diluted in 1% goat serum. Antibody dilutions were as follows: rabbit p38MAPK, phospho-p38MAPK, P-ERK, and ERK polyclonal antibodies (1:500), mouse PDGFR-α monoclonal (1:50), mouse CC1 monoclonal (1:200), mouse CNPase (1:250), mouse GFAP monoclonal clone G-A-5 (1:500), and mouse NeuN (1:400). Sections were washed in 1× PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 three times and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with 1:500 secondary antibody diluted in 1% goat serum. Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 and 546 conjugates for goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse F(ab′)2 fragments (Invitrogen). For triple phosphorylated p38MAPK (P-p38)/P-ERK/CC1 immunostaining, P-p38 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:300; Cell Signaling), P-ERK mouse monoclonal IgG1 antibody (1:300; Cell Signaling), and CC1 mouse monoclonal IgG2b antibody (1:200; Calbiochem) were incubated with brain sections overnight. Secondary antibodies used in the triple immunostain were as follows: anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit F(ab′)2 fragment, Dylight 549-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1, and Dylight 649-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2b monoclonal antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Slices were washed with 1× PBS before mounting in Mowiol. For analysis in tissue sections, a Bio-Rad VMRC 1024 confocal laser-scanning microscope equipped with a crypton–argon laser and an Olympus Optical IX-70 inverted microscope or Zeiss LSM 510 META system were used to image localization of FITC (488 nm laser line excitation; 522/35 emission filter), Texas Red (568 nm excitation; 605/32 emission filter), Cy5 (633 nm excitation; 670/720 emission filter), and 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (405 nm excitation, 417/77 emission). Optical sections (Z = 0.5 μm) of confocal fluorescence images were sequentially acquired using a 40× (numerical aperture, 1.35) oil objective with Bio-Rad LaserSharp, version 3.2, software. ImageJ1.26t and Zeiss LSM Image Examiner software were subsequently used to generate Z-stacks. Merged images were processed in Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems) with minimal manipulation of contrast.

Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell culture.

Primary mixed glial cultures were prepared from embryonic day 20 pregnant Sprague Dawley rats by mechanical dissociation according to the method of McCarthy and de Vellis (1980), as previously described (Gallo and Armstrong, 1995). Ten- to 12-d-old mixed cultures were shaken overnight to detach oligodendrocyte progenitors from the astrocyte monolayer. To minimize contamination by microglial cells, the detached cell suspension was incubated twice in succession for 45 min each in 100 min dishes. OPCs enriched by this method contained >95% GD3+ cells labeled by the LB1 monoclonal antibody (Levi et al., 1986; Curtis et al., 1988), with <5% O4+ cells, <0.05% GFAP+ astrocytes, and <0.05% Ox42+ microglia. The nonadherent cells were seeded on poly-d-ornithine (0.1 mg/ml)-coated 60 mm, and 25 mm coverslips at a density of 3 × 104 cells/cm2 in DME-N1 biotin-containing medium for 1 h before the addition of 10 ng/ml PDGF (human PDGF-AB), 30 ng/ml T3, and 2 μm SB203580, 1 μm U0126, or 100 μm SP600125 prepared in DMSO with an equivalent volume of DMSO added to controls. For time course experiments with PDGF only, OPCs were plated in DMEM for 48 h, and then stimulated with PDGF for up to 4.5 h. For experiments with kinase inhibitors, cells were plated in DME-N1 plus 0.5% FBS for 24 h, and pretreated with DMSO, U0126, SP600125, or SB203580 for 20–30 min before the addition of PDGF in DME-N1.

MTT assay.

Measurements of reduction of MTT were performed according to the manufacturer's directions (TACS MTT assays; R&D Systems); 100 μl of MTT reagent was added to 80,000 cells per well in poly-l-lysine-coated 12-well dishes containing 1 ml of growth media during the final 4 h of incubation. Detergent reagent (300 μl) was then added to each well to solubilize the dark blue crystals overnight. Supernatants (200 μl) were finally transferred to 96-well plates and read on a Molecular Devices ThermoMax 96-well plate reader using a test wavelength of 570 nm.

TUNEL assay.

Fluorescein-dUTP TUNEL assays were performed according to the manufacturer's directions (Promega TUNEL kit). Briefly, OPCs maintained on 25 mm coverslips were fixed in paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and rinsed in PBS. Cells were permeabilized for 5 min in 0.2% Triton X-100, rinsed in PBS, and equilibrated in equilibration buffer for 10 min at room temperature. Each coverslip was incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) incubation mix containing fluorescein-12-dUTP and recombinant TdT enzyme for 1 h at 37°C. Reactions were terminated in 2× SSC for 15 min, washed in PBS, and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI.

Immunostaining in culture.

Live OPCs were stained for cell surface antigens with A2B5, O4, and O1 antibodies as previously described (Yuan et al., 1998). Briefly, cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with primary antibodies diluted 1:10 in DMEM, followed by fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM for 45 min. After washing in PBS, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.3 in PBS, for 10 min at room temperature and mounted in Vectashield (Vector) containing DAPI for total cell estimation. For dual staining with BrdU antibodies, live staining with surface marker antibodies was followed by incubation with secondary antibodies. After washing, paraformaldehyde fixation was followed by treatment of cells with 0.07N NaOH in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were fixed again for 10 min and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. After washing, cells were incubated with 10% goat serum for 15 min followed by monoclonal anti-BrdU antibodies (1:50) for 1–2 h at room temperature, followed by rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for 45 min at room temperature. Coverslips were then mounted in DAPI-containing Vectashield. Using a 40× objective, images of 15–20 microscopic fields per coverslip were collected and at least two coverslips per condition were sampled in each experiment. The total number of cells counted averaged 2000–4500.

Western blotting.

Sample separation on SDS polyacrylamide gels and Western blotting were performed as described previously (Chew et al., 2005). For phosphoproteins, membranes were blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h. Phosphospecific primary antibodies, phospho-p38MAPK, phospho-ERK, phospho-JNK, and phospho-c-Jun, were diluted 1:1000 in 5% BSA and incubated with the membranes at 4°C overnight. For other antibodies, membranes were blocked in 4% nonfat dry milk in TBST. p38MAPK, p44/42 ERK (1:1000; Cell Signaling), MBP (1:2000; SMI99; Covance), MKP3 (1:600; Santa Cruz), and actin (1:2000) were diluted in 4% milk and incubated with the membranes at room temperature for 1 h or 4°C overnight. Protein bands were detected as using SuperSignal West Pico detection kit with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein expression levels in scanned images were quantified using Scion Image.

Reverse transcription–quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) and cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of oligo-dT-primed RNA in a total volume of 20 μl with Thermoscript according to kit instructions (Invitrogen). Two microliters of the first-strand reaction were used for quantitative PCR for myelin-specific markers. A three-step quantitative PCR was performed in Applied Biosystems TaqMan system using the SYBR Green qPCR detection kit (Invitrogen) in a 25 μl reaction with these cycle conditions: 2 min at 50°C (UDG incubation), followed by 35 rounds of cycling at 95°C for 5 min 30 s, 53°C for 45 s, 72°C at 45 s (CT acquisition step), followed by a single final extension step for 4 min at 72°C. A melting curve was obtained for each PCR product after each run with the following conditions: 95°C for 1 min, and then 55 steps of 0.5°C per 20 s decrement beginning at 96°C for 20 s to confirm the presence of a single amplicon. Gene-specific primers were generated with IDT online software and blasted against the mouse genome for specificity. Each qPCR primer pair was validated for unique amplicons by agarose gel electrophoresis after conventional semiquantitative RT-PCR using 1 μl of first-strand reaction. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. GAPDH was used as an internal normalization control because its levels were found not to change as a result of mitogen or kinase inhibitor treatment. After normalization with GAPDH, the fold increase over untreated controls was calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Table 1.

Primers used in real-time PCR assays

| Gene | Orientation | Sequence 5′–3′ | GenBank ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1 | Forward | CTTCAAGTGCGTGCAGAGGGAG | NM_171992.4 |

| Cyclin D1 | Reverse | GTAGTTCATGGCCAGCGGGAAG | |

| CNP | Forward | TACTTCGGCTGGTTCCTGAC | NM_009923 |

| CNP | Reverse | GCCTTCCCGTAGTCACAAAA | |

| MBP | Forward | ATGGCATCACAGAAGAGACCCTCA | M25889 |

| MBP | Reverse | TAAAGAAGCGCCCGATGGAGTCAA | |

| MAG | Forward | TGCCATTGTCTGCTACATCACCCCA | NM_017190 |

| MAG | Reverse | ACTTATCAGGTGCTCCAGAGATTCGG | |

| PLP | Forward | AGCGGGTGTGTCATTGTTTGGGAA | NM_030990 |

| PLP | Reverse | ACCATACATTCTGGCATCAGCGCA | |

| Sox9 | Forward | AGGAAGCTGGCAGACCAGT | NM_011448 |

| Sox9 | Reverse | CGAAGGGTCTCTTCTCGCT | |

| Sox10 | Forward | CGAATTGGGCAAGGTCAAGAAGGA | NM_019193 |

| Sox10 | Reverse | TAAAGGCGTTCATGGGCCGTTTGA | |

| Sox17 | Forward | GATCTGCACAACGCAGAGCTA | NM_011441 |

| Sox17 | Reverse | CCGCTTCTCTGCCAAGGTCAA | |

| GAPDH | Forward | AGACAGCCGCATCTTCTTGT | NM_017008 |

| GAPDH | Reverse | CTTGCCGTGGGTAGAGTCAT |

Sequence and GenBank information of rat-specific primers used in real-time, SYBR Green PCR assays of gene expression.

Plasmids, plasmid construction, transient transfections, and reporter assays.

MBPLuciferase and SoxBSLuc were previously described (Sohn et al., 2006). SoxBSLuc was modified from pH4x4Luc reporter plasmid containing four copies of the H4 site (Kanai et al., 1996). CNP-luciferase reporter plasmid was generated as follows: the luciferase coding region, including SV40 late poly(A) signal, between bases 88 and 1993 (pGl3Basic; Promega), was amplified with HindIII-containing primers using Pfu polymerase and inserted into pCRBlunt (Invitrogen), generating pCRBluntEHLuc. The firefly luciferase-containing HindIII fragment from pCRBluntEHLuc was ligated downstream of the 3.5 kb CNP promoter fragment derived from pBS CNP4.2 (Gravel et al., 1998) by removal of a HindIII fragment containing exon 1. This 3.5 kb CNP promoter fragment was previously verified to target reporter expression specifically to myelin-producing cells in vivo (Yuan et al., 2002).

DNp38α (pCMVp38αAGF-HA) and MEK6 [pcDNA3-Flag-MEK6(Glu)] plasmids were gifts from Dr. Roger Davis (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) (Raingeaud et al., 1996), and pCMV-c-Jun and pCMV-TAM67 expression plasmids were kind gifts from Dr. Michael Birrer (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). pFC-MEK1 encodes a constitutively active mutant of MEK1 (S218/222E, δ32-51), and AP1Luc contains seven direct repeats of the TGACTAA enhancer element upstream of a TATA box. Both plasmids were purchased from Stratagene/Agilent. For transient transfection, OPCs were plated in N1 with 10 ng/ml PDGF at 2.5 × 105 cells per well in six-well poly-l-lysine-coated tissue culture dishes 1–2 d before transfection. Cells in 1.5 ml of N1 plus PDGF received 0.4 μg of luciferase reporter plasmid, 0.8 μg of DNp38α expression vector, and 0.02 μg of SV40-β-galactosidase in 500 μl of N1 with 2.4 μl of Lipofectamine 2000. After overnight incubation, the medium was replaced with N1 plus 10 ng/ml PDGF and harvested 48 h after the start of transfection. For reporter assays with kinase inhibitors, cells were transfected overnight in N1 plus PDGF and allowed to recover after replacing medium with fresh DME-N1 with PDGF and DMSO or kinase inhibitors for an additional 24 h before harvest. Transfected cells were collected in 200 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and 50 μl of lysate assayed for luciferase activity on a Turner 20/20n luminometer (Turner Biosystems). Luciferase activity expressed as relative light units was normalized with total protein content by BCA assay (Pierce) or β-galactosidase activity.

Gene silencing.

siRNA and negative controls were obtained from Ambion. The following two rat p38α siRNA sequences were used (NM_031020): ID53180, sense, GGGCUGAAGUAUAUACACUtt, and antisense, AGUGUAUAUACUUCAGCCCtc; and ID194927, sense, GCUUACCGAUGACCACGUUtt, and antisense, AACGUGGUCAUCGGUAAGCtt. Purified OPCs cultured at 5 × 105 cells per 60 mm poly-l-lysine-coated dishes were treated with 10 ng/ml PDGF for 24 h and then transfected in DME-N1 medium with a 1:1 mixture of p38α siRNAs (final concentration, 80 nm) or siRNA control at equivalent concentration, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 18 h. The medium was replaced with DME-N1 without PDGF, and cells were harvested after an additional 72 h, followed by Western blot analysis. Under these conditions, transfection efficiency with a labeled siRNA control sequence (catalog #1027098; QIAGEN) was estimated at 82 ± 4.3% after 18 h.

Nuclear extract preparation and electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

The nuclear proteins from tissues were extracted by using a rapid method developed by Deryckere and Gannon (1994) with modifications. Approximately 500 mg of tissue was homogenized in 5 ml of solution A [0.6% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.5 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF)] and homogenized with five strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged for 30 s at 2000 rpm. The supernatant was centrifuged for 5 min at 5000 rpm. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in 500 μl of solution B (25% glycerol, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 420 mm NaCl, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm AEBSF, 5 μg/ml pepstatin, leupeptin, and aprotinin) and incubated on ice for 20 min. The lysed nuclei were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and cleared by centrifugation for 1 min. The supernatant was aliquoted into fractions and snap frozen at −80°C. For nuclear extracts from cultured OPCs, 3 × 106 OPCs were dounced with 15 strokes in 1 ml of solution A and nuclei isolated as above. The nuclear pellet resuspended in 100 μl of solution B and processed as above for tissue extracts. Protein concentration of nuclear extracts was determined by BCA assay (Pierce Endogen).

The double-stranded MBP Sox10 probe consisted of nucleotides from −51 to −1 of the mouse MBP promoter (GenBank M24410) as defined previously (Wei et al., 2004): 5′-GAGGGAGGACAACACCTTCAAAGACAGGCCCTCAGAGTCCGACGAGCTTC-3′. The MBP AP1-like sequence was 5′-CTACCCACTGTCGATGACTTATTGATTAGAG-3′ (Miskimins and Miskimins, 2001). The consensus SP1 probe was 5′-ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC-3′, and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-responsive element (TRE) AP1 was 5′-CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3′. All probes were annealed in water and end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP, purified on G50 columns, and used in gel shift assays. The reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μl of binding buffer containing 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 60 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, and 50 μg/ml poly(dI-dC). The binding reactions were incubated on ice for 30 min with 4–12 μg of nuclear proteins from cell and tissue extracts. Ten femtomoles of labeled probe were added to each reaction and incubated for another 30 min on ice. In competition experiments, the unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides were used in 100-fold molar excess. For supershifts, 1–2 μl of SP1, P-c-Jun, or Sox10 antibody was added to the reactions 15–30 min before loading. After adding 1 μl of 0.1% bromphenol blue loading dye, each reaction was directly loaded onto a 4% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel and resolved at 100 V. The gels were then dried and autoradiographed on x-ray film for 16–36 h.

Results

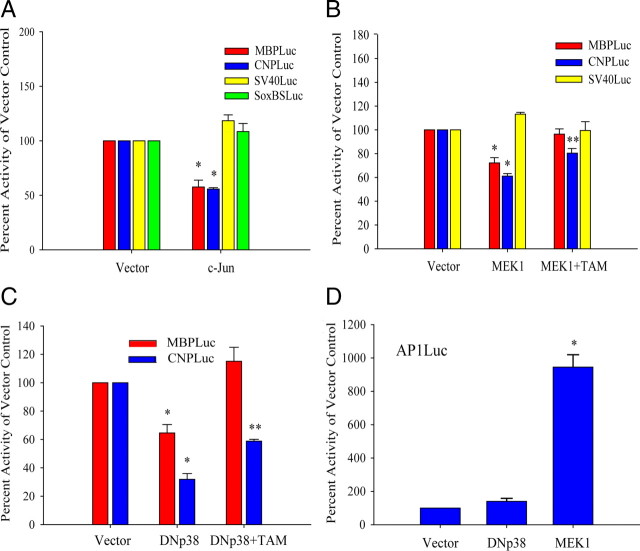

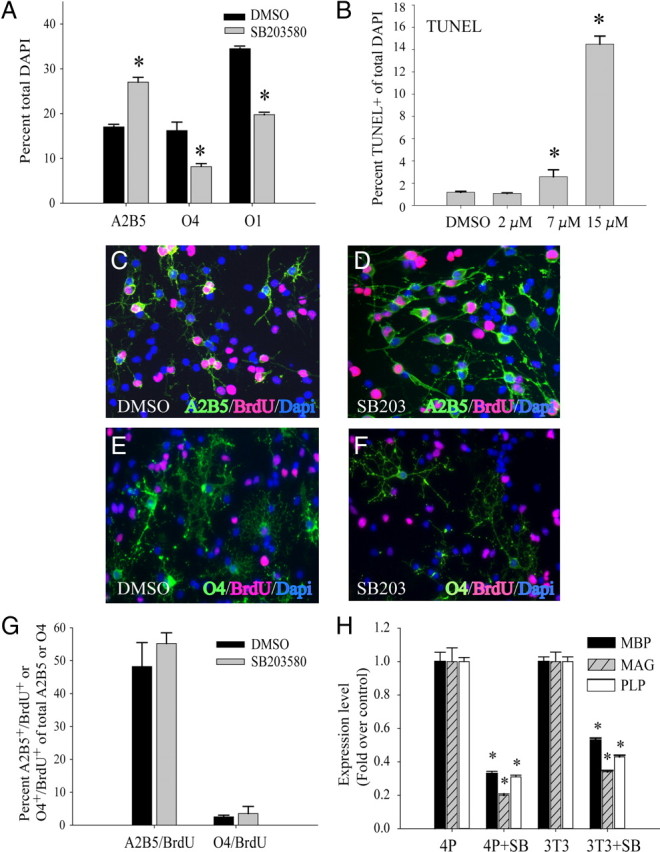

p38MAPK inhibition attenuates OPC differentiation without effect on proliferation or survival

To analyze the effect of p38MAPK inhibition on OPC differentiation, primary OPC cultures were maintained for 3 d in the presence of PDGF to initiate cell proliferation and lineage progression to the O4+ stage, whereas differentiation to the O1+ stage required PDGF withdrawal after an initial 24 h in PDGF. The application of 2 μm SB203580 at the time of plating resulted in significant decreases in O4+ and O1+ cells, as well as increased percentages of A2B5+ cells (Fig. 1A). Similar results were obtained with 1 μm SB202190 (data not shown). The dose of SB203580 applied was chosen based on apoptosis assays (Fig. 1B). Doses >5 μm were toxic to OPCs in PDGF, whereas lower doses were not, as apoptosis measured by TUNEL assay was significant until 7 μm was applied (Fig. 1B). In addition, cell growth was also not significantly affected under these conditions, in the absence and presence of PDGF (supplemental Fig. 1A, MTT assay, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Furthermore, these doses have been reported to be particularly selective for p38MAPK (Bain et al., 2007). Using 2 μm SB203580, proliferation assays with BrdU were performed to determine whether the changes in percentages of A2B5+ cells were associated with changes in S-phase activity. Figure 1, C and D, shows that BrdU incorporation by A2B5+ cells occurs in control and SB203580-treated cells and that significant differences in proliferation of these cells were not observed (Fig. 1G). The reduced percentages of O4+ cells were also not accompanied by changes in proliferation (Fig. 1E–G), as most of these cells in culture were postmitotic. Dose–response studies showed that overall BrdU incorporation in the presence of SB203580 was not significantly different from controls (supplemental Fig. 1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). No changes were observed in the expression levels of cell cycle regulators of the G1, or G2/M checkpoints such as p27, cyclin D1, cdk2, and phosphorylated cdc2 (supplemental Fig. 1C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). All subsequent studies were performed with 2 μm SB203580. The inhibition of OPC maturation was also accompanied by a significant reduction in the RNA levels of MBP, myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), and proteolipid protein (PLP) as measured by quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (Fig. 1H). The effect of SB203580 on differentiation or myelin gene expression was not altered by the differentiation paradigm, as changes in RNA levels of myelin genes after mitogen removal and treatment with thyroid hormone were very similar (Fig. 1H).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of p38MAPK prevents OPC differentiation without affecting proliferation. A, Immunocytochemical characterization of OPC cultures grown in PDGF for 48 h followed by mitogen withdrawal and T3 treatment for an additional 48 h. Chronic treatment with 2 μm SB203580 results in an increase in A2B5+ cells and reduction in O4+ and O1+ populations. Values are expressed as a percentage of total cells identified by DAPI nuclear staining. *p < 0.05 (Student's t test) versus respective DMSO-treated controls. B, TUNEL assay of OPCs cultured for 3 d in PDGF with increasing concentrations of SB203580 added at the time of plating. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *p < 0.05 (Student's t test) compared with DMSO. C–F, Immunocytochemical analysis of proliferation in OPCs. A2B5+ (green; C, D) and O4+ (green; E, F) were double labeled with BrdU (red). Cells were maintained for 3 d in PDGF in the presence of 2 μm SB203580 (SB203) or DMSO vehicle. Nuclei stained by DAPI are shown in blue. G, Quantification of images shown in C–F as a percentage of total A2B5+ or O4+ cells. Two micromolar p38MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (SB) was used. Values shown are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. H, Reverse transcription/real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis of myelin gene RNAs: MBP, MAG, and PLP show reduction under different culture conditions (4P, 4 d with PDGF; 3T3, 1 d in PDGF followed by 3 d with T3) with 2 μm p38MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (SB). *p < 0.05 (Student's t test) compared with DMSO. Values are mean ± SEM of three experiments.

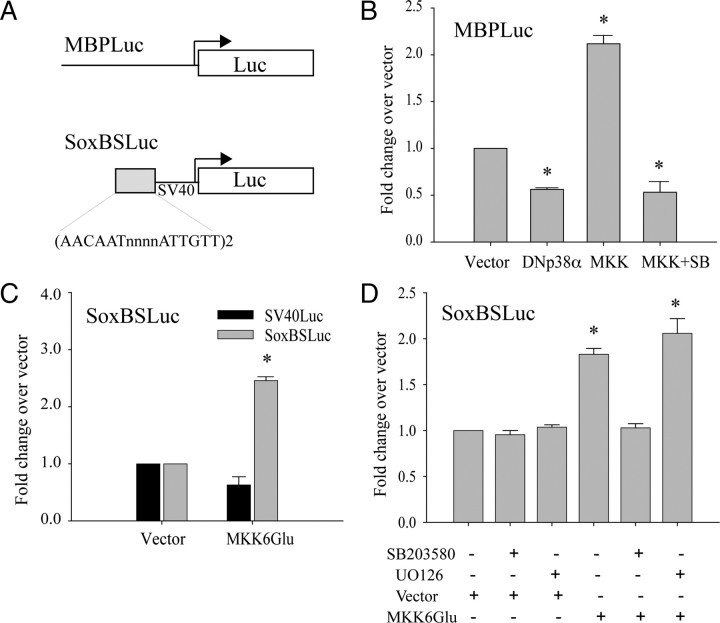

p38MAPK modulation of MBP promoter and Sox-dependent promoter activities

To investigate whether myelin gene expression was modulated by p38MAPK at the transcriptional level, reporter assays were performed in primary OPCs. The reporters used in these experiments are shown in Figure 2A. The MBP promoter consists of a 2 kb 5′ flanking fragment previously reported to respond positively to Sox10 and Sox17 cotransfection (Sohn et al., 2006). MBP promoter activity was downregulated by cotransfection of a dominant-negative p38MAPKα expression plasmid, DNp38α (Fig. 2B). Conversely, cotransfection with a plasmid encoding a constitutively active form of the p38MAPK upstream kinase, MEK6 (MKK6Glu), resulted in upregulation of MBP promoter activity (Fig. 2B, MKK) that was blocked by the addition of SB203580. These results suggest that p38MAPK activity upregulates the activity and/or expression of transcription factors that can bind the 2 kb mouse MBP promoter. The concerted downregulation of multiple myelin gene products by p38MAPK (Fig. 1) suggests a pivotal contribution of p38MAPK in progenitor commitment that can be accomplished through a myelin transcription factor such as Sox10. The SoxBSLuc reporter has been shown to be regulated by both Sox10 and Sox17 (Sohn et al., 2006). Assays using the SoxBSLuc reporter indicate that MEK6 activated the Sox-dependent heterologous promoter (Fig. 2C) and that a control reporter lacking the Sox binding site was not modulated by MEK6 (Fig. 2C, SV40Luc). Specific inhibitors were included to identify the transcriptional effector of MEK6. In Figure 2D, MEK6-regulated SoxBSLuc activity could only be modulated by SB203580, and not by MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126, indicating that Sox protein(s) constitute a downstream target of p38MAPK activity.

Figure 2.

Transcriptional regulation by p38MAP kinase in primary OPCs. A, Luciferase reporter plasmids used in reporter assays. SoxBSLuc contains two inverted AACAAT motifs. B, Cotransfection assays in primary OPC cultures showing induction of MBP promoter activity by the constitutive active MEK6 mutant, MKK6Glu (MKK), and inhibition by a dominant-negative p38αAGF mutant (DNp38α). MKK-induced MBP promoter activity was abolished by SB203580 (MKK+SB). Values were normalized against total protein content. *p < 0.05 versus vector, Student's t test. C, Cotransfection assays showing that the induction of luciferase activity by MKK6Glu is dependent on the presence of Sox transcription factor binding sites (SoxBS). SV40Luc is the parent plasmid lacking Sox binding sites. *p < 0.001 versus vector, Student's t test. D, Reporter assays showing the induction of SoxBSLuc activity by MKK6Glu is blocked selectively by the inclusion of 2 μm SB203580 and not by 1 μm U0126 (MEK1/2 inhibitor) at the medium change. The transfected cells were treated with kinase inhibitors for 24 h before analysis. *p < 0.05 versus vector, Student's t test. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

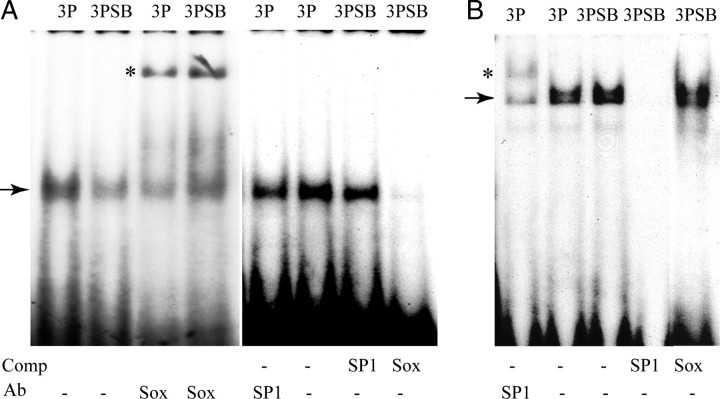

p38MAPK inhibition attenuates Sox10 DNA binding

Since p38MAPK inhibition represses Sox-dependent promoter activity, and because Sox10 is known to coordinately regulate the expression of multiple myelin genes (Britsch et al., 2001), we investigated whether p38MAPK modulates Sox10 function and/or expression. Changes in Sox10 function in nuclear extracts prepared from OPCs were assessed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). OPCs were treated with 2 μm SB203580 for 3 d, and DNA binding assays performed using the MBP Sox10 recognition site as a probe. p38MAPK inhibition reduced protein complex formation on the probe (Fig. 3A). The complex containing Sox10 was specific, because SP1 consensus binding site did not abolish DNA complex formation (Fig. 3A), and was recognized by a Sox10 antibody, but not by an SP1 antibody (Fig. 3A). To demonstrate specificity of these changes, an SP1 probe was used in a similar experiment. As shown in Figure 3B, the application of SB203580 did not affect complex formation at the SP1 consensus sequence. The reduction in Sox10 DNA-binding activity by SB203580 could be attributable to phosphorylation by p38MAPK, as quantitative PCR analysis showed no significant change in Sox10 RNA levels (Table 2). Under these conditions, the levels of Sox9, Sox10, Sox17, and cyclin D1 RNA were also unaffected by p38MAPK inhibition (Table 2), suggesting that, in the presence of PDGF, p38MAPK regulated the functional activity, rather than the transcription of positive regulator(s) of myelin gene expression.

Figure 3.

Regulation of Sox10 DNA-binding activity and expression by p38 MAP kinase activity. A, B, EMSAs with OPC extracts showing decreased Sox10 (A) and unchanged SP1 (B) DNA binding after treatment with 2 μm SB203580 (SB). OPCs were maintained in PDGF for 3 d. The arrows indicate specific DNA–protein complexes, and the asterisks (*) denote supershifted complexes. Lanes where specific antibodies (Ab) or 100-fold molar excess unlabeled oligonucleotide competitor (Comp) are included in the reactions are indicated below the images. The Sox antibody used was specific for Sox10.

Table 2.

p38MAPK inhibition does not affect steady-state levels of Sox and cyclin D1 transcripts

| Gene | Control (mean) | SB203580-treated (mean fold change over control) |

|---|---|---|

| MBP | 1 | 0.632 ± 0.0239** |

| Sox9 | 1 | 0.962 ± 0.0626 |

| Sox10 | 1 | 0.982 ± 0.0801 |

| Sox17 | 1 | 0.843 ± 0.0348 |

| Cyclin D1 | 1 | 1.127 ± 0.0882 |

RNA was extracted from OPCs maintained in PDGF in the presence or absence of 2 μm SB203580 for 4 d. Expression levels were analyzed by reverse transcription followed by real-time PCR analysis. The data were normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold change over controls. Values represent mean ± SEM for three to five independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Statistical comparisons were made to control values by unpaired Student's t test.

**p < 0.001.

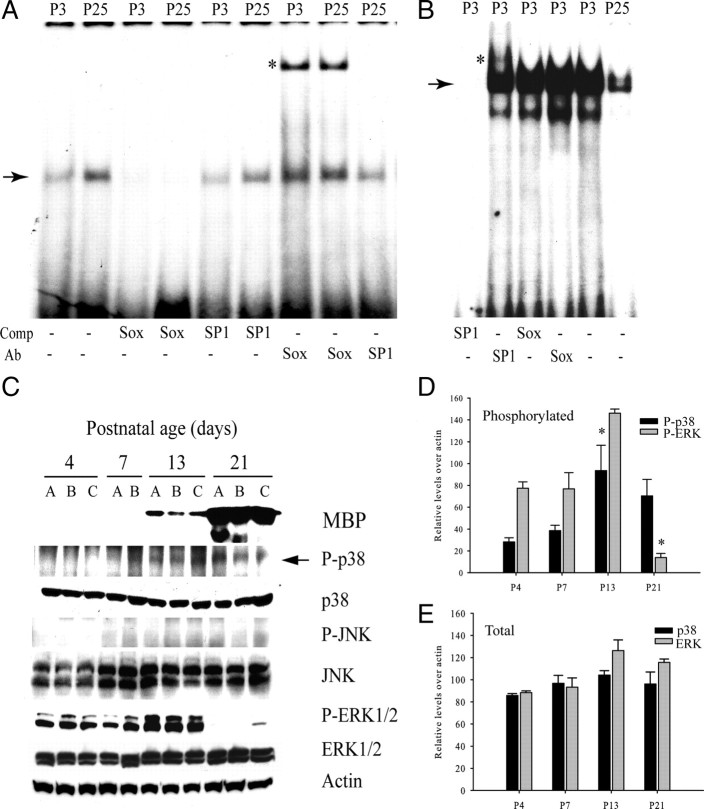

Developmental regulation of Sox10 DNA binding and p38MAPK activation in white-matter tissue

Based on our findings in cultured OPCs, we hypothesized that Sox10 DNA binding activity could be temporally associated with an increase in the levels of p38MAPK phosphorylation during developmental myelination. In gel shift assays with nuclear extracts from corpus callosum tissue, the formation of DNA complexes on a Sox10 binding site of the MBP promoter is observed to be developmentally regulated, showing an increase in complex formation between P3 and P25 (Fig. 4A,B). Sox10 binding was detected at both P3 and P25, and the relative difference in complex intensity was unchanged in the presence of an unrelated DNA competitor (Fig. 4A, Comp SP1). When corpus callosum tissue was analyzed by Western blotting, phosphorylated p38MAPK levels were indeed also found to be upregulated between P4 and P21, with readily detectable levels appearing coincidentally with MBP protein at P13 (Fig. 4C). Quantification of these blots (Fig. 4D,E) revealed that the changes in the levels of phosphorylated kinases were not likely to be attributable to changes in the levels of the kinases themselves, as significant changes in total kinase content were not apparent (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Changes in Sox10 DNA binding, and phosphorylation levels of MAP kinases during postnatal white-matter development. A, B, EMSAs showing increased DNA binding between P3 and P25 in rat brain extracts with the MBP Sox10 probe (A) and a decrease in SP1 binding with a canonical SP1 probe (B). The arrows indicate specific DNA–protein complexes, and the asterisks (*) denote supershifted complexes with the indicated antibodies (Ab). The Sox antibody was specific for Sox10. Comp, 100-fold excess unlabeled competitor included to show probe specificity. C, Analysis of MAPK phosphorylation in relation to total MAPK protein and MBP expression in the developing rat corpus callosum. Western blot of total protein lysates extracted from rat anterior corpus callosum at the indicated time points of P4, P7, P13, and P21 in rats. MBP, as well as both phosphorylated and total forms of p38, JNK, and ERK1/2 are shown. Samples A–C denote two to three individual brains at the indicated postnatal ages. Western blot shows increased P-p38 (arrow) coincident with the appearance of MBP in samples obtained from anterior corpus callosum at postnatal ages days 4 through 21. Phosphorylated JNK (P-JNK) (Thr183/Tyr185) was undetectable. D, Histogram showing developmental regulation of phosphorylated kinase levels in white-matter tissue after densitometric quantification of Western blots similar to and including samples shown in C. Values were normalized against actin. *p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. P-p38 at P13 was significantly higher than at P4 or P7, and P-ERK at P21 was lower than at all other time points. E, Histogram similar to D showing comparison of levels of total p38 and ERK after densitometric scanning and normalization against actin. No significant differences were found. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Although our studies have thus far been consistent with the promotion of Sox10 function by p38MAPK activity, it is also possible that p38MAPK negatively regulates inhibitors of myelin gene expression. Given previous evidence of kinase cross talk (Xia et al., 1995; Lavoie et al., 1996), it is likely that the activities of different MAP kinases may be preferentially regulated during white-matter development. In the same samples, activated JNK was not detected, but interestingly, P-ERK showed a clear decline by P21 when MBP protein is dramatically upregulated (Fig. 4C). The decline in P-ERK is in agreement with the studies of Horiuchi et al. (2006), who had described decreased phosphorylated ERK levels in differentiating OPCs in culture. These observations suggest a functional relationship between p38MAPK, ERK activity, and the onset of myelination.

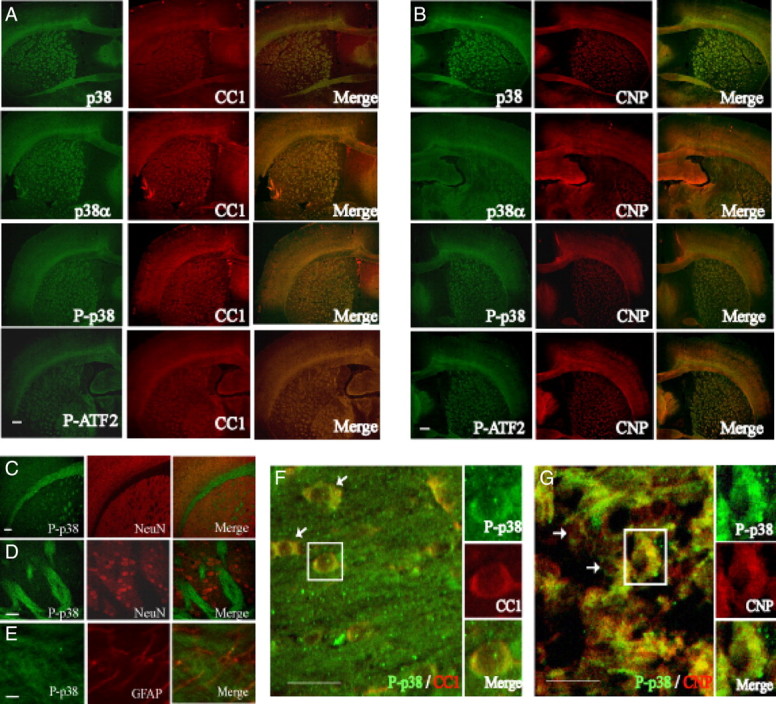

p38MAPK is enriched in oligodendrocyte cells of the white matter

Since p38MAPK inhibition prevents myelin gene expression and OPC differentiation, we hypothesized that p38MAPK phosphorylation in the oligodendrocyte lineage may be associated anatomically with myelinating cells of the white matter. To determine the cellular distribution of p38MAPK expression and activity in vivo, immunohistochemistry was performed in the adult mouse brain. Figure 5 shows that immunological detection in P40 brains showed similar patterns not only with a pan-p38MAPK antibody but also with antibodies specific for p38α, P-p38, and its substrate P-ATF2. The labeling was selectively enriched in myelinated structures of the subcortical white matter, corpus callosum, striatum and anterior commissure, external capsule, and fimbria, colocalizing with CC1 (Fig. 5A) and CNP (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Distribution of p38MAPK and phosphorylated p38 immunoreactivity in the adult mouse brain at P40. A, p38, p38-α, P-p38, and phosphorylated ATF2 (P-ATF2) (all in green) immunoreactivity are colocalized with CC1 (red) in merged images (yellow). B, CNPase (CNP) (red) is also colocalized with p38, p38-α, P-p38, and P-ATF2 (all in green). Scale bars: A, B, 200 μm. C, Regions of high p38MAPK phosphorylation (green) do not colocalize with NeuN immunostaining (red). Scale bar, 100 μm. D, Confocal view at 40× of striatal region shown in C. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, Confocal image showing little phosphorylated p38MAPK (green) in GFAP-expressing astrocytes (red) of the corpus callosum. Scale bar, 50 μm. F, G, Confocal images of CC1- and CNP-expressing cells. F, Localization of phosphorylated p38MAPK (green) in white-matter CC1+ cells (red). Cells in boxes are enlarged alongside main panel. The arrows denote other cells with cytoplasmic P-p38 staining. G, CNP+ cells (red) in white matter coexpress P-p38 (green). Scale bars: F, G, 25 μm.

p38α is the primary isoform expressed in the rodent oligodendroglial cells, along with relatively lower levels of p38γ (Fragoso et al., 2007; Haines et al., 2008), so it is likely that P-p38 detected in this lineage may consist primarily of P-p38α. P-p38MAPK immunoreactivity did not colocalize with NeuN-positive cell bodies (Fig. 5C,D), suggesting that sustained p38MAPK activity was not associated with neuronal development. P-p38MAPK was also not associated with GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 5E), suggesting a selective function in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Figure 5, F and G, indicates that phosphorylated p38MAPK is found primarily in the cytoplasm of CC1+ and CNP+ cells.

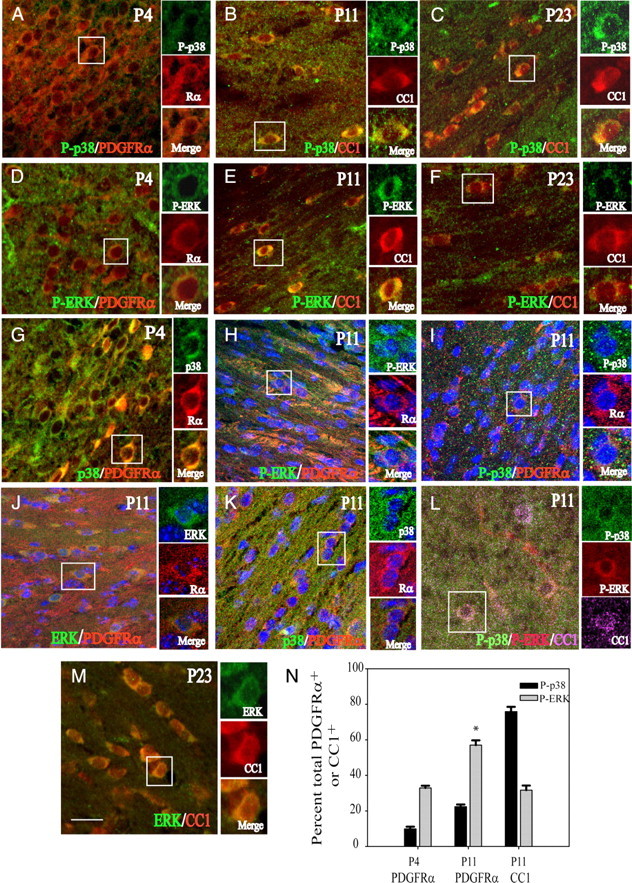

Since the analysis of MAPK activity in white-matter tissue by Western blotting suggested a developmental relationship between the phosphorylation levels of p38MAPK and ERK (Fig. 4C,D), it is possible that these patterns of p38MAPK and ERK activity would also be observed at the cellular level. Immunocytochemical analysis in the subcortical white matter and corpus callosum indicates that p38MAPK phosphorylation is low in PDGFRα-expressing progenitor cells, and increases from P11 through P23 in CC1+ cells (Fig. 6A–C), whereas ERK phosphorylation is detectable between P4 and P11, and declines by P23 (Fig. 6D–F). These changes are primarily attributable to phosphorylation status and not expression levels of the kinases per se, because total (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) p38MAPK and ERK protein levels are not significantly regulated throughout white-matter development (Fig. 4C,E). Although p38MAPK protein was readily detectable in PDGFRα-expressing cells (Fig. 6G,K), its phosphorylated form, P-p38, is only found at low levels in <30% of PDGFRα+ OPCs between P4 and P11 (Fig. 6N, P-p38). In contrast, the large majority (80%) of CC1+ cells at P11 show clear positive immunoreactivity for P-p38 (Fig. 6B,N).

Figure 6.

p38MAPK and ERK phosphorylation in oligodendrocyte lineage cells of the developing white matter. A–I, Confocal images of oligodendrocyte lineage cells in the subcortical white matter between the ages of P4 and P23. A–C, Images of phosphorylated p38 (P-p38) (green) with PDGFRα (Rα) (red) or CC1 (CC1) (red) at P4, P11, and P23. Low levels of P-p38 are present in PDGFRα cells at P4. D–F, Colocalization of P-ERK (green) with PDGFRα (Rα) (red) or CC1 (red) at P4, P11, and P23. At P11, P-ERK is found in CC1+ cells near the cingulum region (E). G, Presence of total p38MAPK (green) in PDGFRα+ cells (red) at P4. H, Phosphorylated ERK (green) in PDGFRα+ cells (Rα) (red) at P11. I, Very low levels of P-p38 (green) in PDGFRα+ cells (Rα) (red) at P11. J, K, Total ERK (J; green) and p38MAPK levels (K; green) are readily detected in PDGFRα+ cells (Rα) (red) at P11. L, Overlapping P-p38 (green) and P-ERK (red) localization in CC1+ (purple) cells. In H–K, nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). M, Total ERK (green) protein in CC1+ (red) cells at P23. Scale bar, 25 μm. N, Histogram illustrating the percentages of PDGFRa and CC1+ cells that were colocalized with P-ERK or P-p38 at P4 and P11. *p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. There are significantly greater numbers of PDGFRα+ cells with P-ERK at P11 than at P4. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

ERK protein was not found at high levels in GFAP+ white-matter astrocytes at P11 (supplemental Fig. 3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Phosphorylated ERK was found in only ∼30% of CC1+ cells at P11 (Fig. 6E,N). Given the high percentage of CC1+ cells that are positive for P-p38 (Fig. 6N), it is therefore not surprising that at P11, some CC1+ cells at P11 were found by triple immunolabeling to be positive for both P-p38 and P-ERK (Fig. 6L), albeit at reduced intensity. Although ERK protein is readily colocalized with PDGFRa (Fig. 6J), phosphorylated ERK was detected in 33–60% PDGFRa+ cells between P4 and P11 (Fig. 6D,H,N). This decline in detection of phosphorylated ERK on OPC maturation is in agreement with the findings of Horiuchi et al. (2006) with cultured OPCs. Together with the abundance of P-p38 in CC1+ cells, these findings indirectly support the notion of a functional relationship between p38MAPK and ERK.

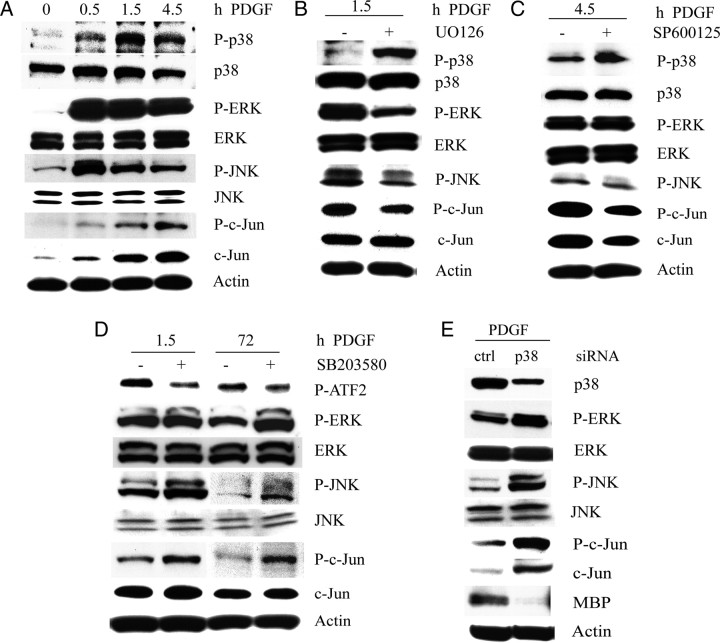

p38MAPK antagonizes ERK, JNK, c-Jun phosphorylation

The observation of an apparent developmental relationship between p38MAPK and ERK phosphorylation levels in white-matter tissue would indicate that p38MAPK may antagonize ERK function during oligodendrocyte development. This would imply that the MEK/ERK pathway negatively regulates myelin gene expression. Our experimental paradigm of lineage progression in vitro uses PDGF (Fig. 1). PDGF is known to stimulate the p38MAPK, ERK, and JNK pathways, so that potential interactions among these MAPK-dependent pathways may be investigated in cultured OPCs using pharmacological MAPK inhibitors in the presence of PDGF.

To begin to understand functional relationships among MAP kinases, a time course experiment of PDGF exposure was performed. Under basal conditions in DMEM, PDGF acutely stimulated the phosphorylation of ERK, p38MAPK, and JNK, but showing slightly different kinetics, with the peak of ERK and JNK phosphorylation preceding that of p38MAPK (Fig. 7A). The slightly delayed induction of p38MAPK phosphorylation compared with P-ERK suggests a role for early events that in turn stimulate p38MAPK activation (Fig. 7A). Since ERK phosphorylation is detected in white matter before p38 phosphorylation (Figs. 4C,D, 6), it remains possible that ERK may be involved in temporally regulating the levels of p38 activation.

Figure 7.

p38MAPK is involved in kinase pathway cross talk. A–E, Western blot analyses showing MAPK phosphorylation by PDGF in cultured OPCs. A, PDGF acutely stimulates the phosphorylation of multiple kinases. OPCs were plated in only DMEM for 48 h before treatment with PDGF for the indicated times. Note that the peak of p38MAPK phosphorylation is delayed compared with JNK and that c-Jun shows gradual accumulation over 4 h. B, Inhibition of ERK phosphorylation promotes p38 phosphorylation. OPCs were plated in DME-N1 plus 0.5% FBS and treated with PDGF in the absence and presence of 1 μm U0126 for 1.5 h. U0126 was applied 20 min before addition of PDGF. U0126 also reduces P-c-Jun levels. C, Inhibition of JNK activity promotes p38 phosphorylation. OPCs were plated in DME-N1 as in B and pretreated with 100 nm SP600125 for 20 min before addition of PDGF for an additional 4.5 h. D, Inhibition of p38MAPK with SB203580 elevates P-ERK, P-JNK, and P-c-Jun levels after 72 h. OPCs were cultured in DME-N1 as in B and treated with 2 μm SB203580 20 min before PDGF addition. E, Knockdown of p38α elevates the levels of phosphorylated ERK, JNK, and c-Jun. OPCs were transfected with 80 nm p38α siRNA 24 h after culture in PDGF and analyzed 48 h after transfection.

To analyze the effect of kinase inhibition on PDGF-induced p38MAPK phosphorylation, OPCs maintained in N1 were preincubated with MEK and JNK inhibitors before stimulation with PDGF. Pretreatment of OPCs with the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 not only reduced PDGF-stimulated ERK phosphorylation but also elevated p38MAPK phosphorylation, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between p38MAPK and ERK (Fig. 7B). p38MAPK phosphorylation was also increased by application of a JNK inhibitor, SP600125 (Fig. 7C). Thus, ERK and JNK activities support c-Jun phosphorylation and may negatively regulate p38MAPK.

Based on a previous report that p38MAPK suppresses JNK activity (Lahti et al., 2006; Hui et al., 2007), we hypothesized that the inhibition of p38MAPK could de-repress the activation of ERK and/or JNK in OPCs. In controls, the PDGF-stimulated increase in P-c-Jun declines with time (Fig. 7A,D), whereas on p38MAPK inhibition with SB203580, P-c-Jun is induced acutely and remains elevated even after 3 d (Fig. 7D). SB203580 is known to specifically inhibit p38α and p38β, and based on the high levels of the former in these cells, it is likely that p38α is mediating these effects on ERK and JNK. To confirm that the effects of SB203580 on MBP and P-c-Jun levels were not attributable to nonspecific pharmacological artifacts and off-target responses, we transfected OPCs in PDGF with siRNA against p38MAPKα and observed that the 70% reduction in p38α protein levels was accompanied by reduced MBP protein expression, along with elevated P-ERK, P-JNK, and P-c-Jun when analyzed at 48 h after transfection (Fig. 7E). These findings show that the inhibitory effects of p38MAPK inactivation on OPC differentiation could be mediated, at least in part, through cross talk with other MAPK pathways, potentially involving their downstream effectors as negative regulators.

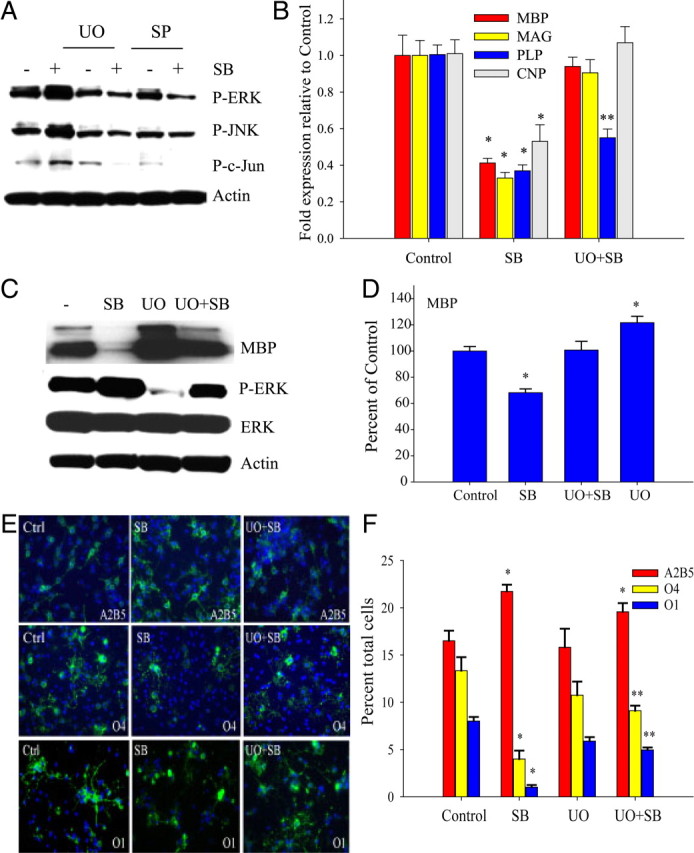

ERK and JNK pathways mediate the inhibitory effects of SB203580 on OPC development

To test whether the ERK- and JNK-dependent pathways could modulate p38MAPK-dependent OPC lineage progression and myelin gene expression, we inhibited ERK/JNK phosphorylation using specific kinase inhibitors. Preincubation of OPC cultures with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (1 μm) and JNK inhibitor SP600125 (100 nm) not only prevented the SB203580-induced upregulation of P-ERK and P-JNK levels, but also that of phosphorylated c-Jun (Fig. 8A). Analysis of myelin gene expression revealed that U0126 prevented the repression of MBP, CNP, and MAG RNA levels by SB203580 (Fig. 8B). U0126 pretreatment also prevented the attenuation of MBP protein levels (Fig. 8C,D). The inhibition of morphological differentiation as assessed by A2B5, O4, and O1 immunostaining was also found to be partially alleviated by U0126 pretreatment (Fig. 8E,F). One micromolar U0126 alone did not show significant effects by immunocytochemistry when compared with untreated controls, nor did it reduce the percentage of A2B5+ cells (Fig. 8F). However, U0126 elicited statistically significant effects on the percentages of O4+ and O1+ cells in the presence of SB203580.

Figure 8.

MEK1 inhibition attenuates the repression of OPC differentiation induced by p38MAPK inhibition. A, Western blot showing that preincubation with 1 μm U0126 (UO) for 30 min before addition of SB203580 inhibits the SB203580-induced elevation of P-ERK, and P-JNK. Preincubation with 100 nm SP600125 inhibits SB203580-induced elevation of P-ERK and P-JNK, and P-c-Jun. OPCs were plated in N1 plus PDGF and treated with 2 μm SB203580 for 3 d. B, Thirty minute pretreatment with 1 μm MEK inhibitor U0126 (UO) partially prevents SB203580-mediated downregulation of myelin genes, but not of Sox10 RNA. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of OPCs shows significant elevation of MBP, MAG, and PLP RNA levels by 1 μm U0126 in the presence of 2 μm SB203580 (UO+SB) after 4 d in PDGF (4P). *p < 0.05 versus control. **p < 0.05 versus control and SB (i.e., PLP RNA in UO+SB was significantly different from SB and control); one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. C, One micromolar U0126 (UO) prevents MBP protein downregulation by 2 μm SB203580 (SB). Western blot analysis was performed after 4 d in PDGF. Culture conditions were similar to B. D, Densitometric analysis of four Western blotting experiments similar to C. MBP levels were normalized against actin and expressed as percentage of control. *p < 0.05 versus control and UO+SB; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. E, OPC lineage progression is partially restored by 1 μm MEK inhibitor U0126. Immunofluorescence shows that U0126 partially prevents the SB203580-mediated increase in A2B5+ and reduction in O4 and O1 antigen (green) immunostaining after 3 d in PDGF (A2B5, O4) and 2 d after PDGF withdrawal (O1). Note increased branching of O4+ and O1+ cells in the presence of U0126. F, Quantification of E shows U0126 at 1 μm (UO+SB) attenuates the inhibitory effect 2 μm SB203580 (SB) on OPC lineage progression from A2B5+ to O4 and O1 (GalC+) stages. Values are expressed as percentage total DAPI+ nuclei. *p < 0.05 versus control; **p < 0.05 versus respective control and SB; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test, with four independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

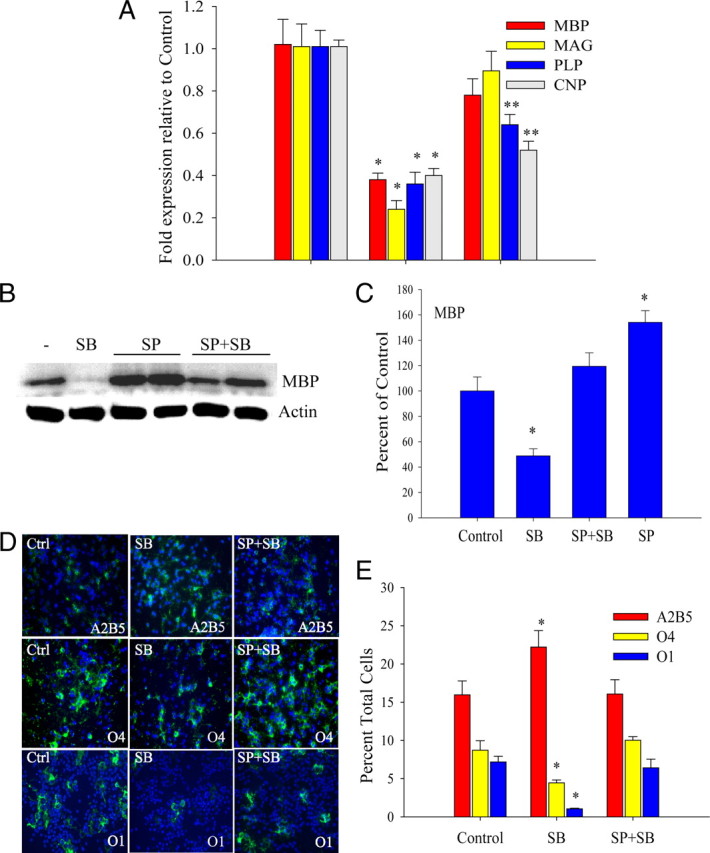

Significant changes in myelin gene mRNA (Fig. 9A) and in MBP protein (Fig. 9B,C) were also observed after pretreatment of OPCs with the JNK inhibitor SP600125. The changes in the percentages of A2B5, O4, and O1 cells induced by SB203580 were effectively abolished by JNK inhibition (Fig. 9D,E). Previous experiments showed that these doses of U0126 and SP600125 used were found not to affect cell survival or growth as indicated by TUNEL assay (supplemental Fig. 2A,B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and total cell counts using DAPI staining (supplemental Fig. 2C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These studies indicate that the antagonism of ERK and JNK activity by p38MAPK plays an important role in the regulation of OPC lineage progression.

Figure 9.

JNK inhibition attenuates repression of OPC differentiation by p38MAPK inhibition. A, Thirty minute pretreatment with 100 nm JNK inhibitor SP600125 (SP) attenuates SB203580-mediated downregulation of myelin gene expression. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of OPCs shows significant elevation of MBP, MAG, PLP, and CNP RNA levels by SP600125 in the presence of 2 μm SB203580 (SP+SB) after 4 d in PDGF (4P). *p < 0.05 versus control; **p < 0.05 versus control and SB; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. B, The 100 nm SP600125 (SP) prevents MBP protein downregulation by 2 μm SB203580 (SB). Western blot analysis was performed after 4 d in PDGF. Culture conditions were similar to B. Two separate samples are shown for each condition of SP and SP+SB. C, Densitometric analysis of four Western blotting experiments similar to B. MBP levels were normalized against actin and expressed as percentage of control. *p < 0.05 versus control and SP+SB; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. D, OPC lineage progression is partially restored by 100 nm JNK inhibitor SP600125. Immunofluorescence shows that SP600125 prevents the SB203580-mediated increase in A2B5+ and reduction in O4+ and O1+ cells after 4 d in PDGF (A2B5, O4) and 2 d after PDGF withdrawal (O1). E, Quantification of D shows SP600125 at 100 nm (SP+SB) attenuates the inhibitory effect of 2 μm SB203580 (SB) on OPC lineage progression from A2B5+ to the O4+ and O1+ (GalC+) stages. Values are expressed as percentage total DAPI+ nuclei. *p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test. All data represent means ± SEM of three to five independent experiments.

c-Jun mediates myelin gene promoter repression by MEK1 and p38MAPK inhibition

As both ERK and JNK pathways regulate c-Jun phosphorylation (Fig. 7B,C), and because c-Jun has been shown in Schwann cells to antagonize the promyelinating effects of Krox20 (Parkinson et al., 2004, 2008), we hypothesized that elevated levels of phosphorylated c-Jun could negatively regulate the transcriptional activity of myelin genes in primary OPCs. We analyzed the effect of Jun activity on the MBP and CNP promoter response by reporter assay in transiently transfected OPCs. c-Jun overexpression, through cotransfection with pCMV-c-Jun, selectively downregulated the activities of both myelin gene promoters but did not affect either the SoxBS binding site or the control SV40 promoter (Fig. 10A). This suggests that the effects of c-Jun are independent of Sox binding activity and that p38MAPK regulation of Sox10 and ERK/JNK activities constitute separate pathways.

Figure 10.

Negative regulation of myelin gene promoter activity by MAPK activity involves c-Jun. OPCs were cultured in PDGF for 2 d before transient transfection. A, Overexpression of c-Jun selectively downregulates the activities of the MBP and CNP promoters. OPCs were cotransfected with reporter plasmids and pCMV-c-Jun or empty vector for 18 h and allowed to recover without PDGF for 48 h before analysis. Luciferase values were normalized with total protein concentration or with cotransfected SV40β-galactosidase plasmid. Fold change in luciferase activity is expressed as a ratio of normalized luciferase activity with pCMV-c-Jun to normalized vector-cotransfected controls. *p < 0.005 versus vector control, Student's t test. B, MEK activity represses myelin gene promoter activity that is reversible with c-Jun inhibition. OPCs were cotransfected with reporter plasmids and pcDNA3.1 (vector) or pFC-MEK1 (MEK1) in the absence and presence of pCMV-TAM67 (TAM). TAM67 partially but significantly attenuates MEK-induced repression of CNPLuc. MBPLuc and SV40Luc in the TAM-transfected groups were not significantly different from controls. *p < 0.05 versus vector; **p < 0.05 versus vector and MEK1; one-way ANOVA, Holm–Sidak test. C, Effects of p38α inhibition on MBPLuc and CNPLuc are attenuated by TAM67. OPCs were cotransfected with reporter plasmids and pcDNA3.1 (vector) or dominant-negative p38αAGF mutant (DNp38) in the absence or presence of pCMV-TAM67 (TAM). *p < 0.05 versus vector; **p < 0.05 versus vector and DNp38; one-way ANOVA, Holm–Sidak test. All data represent means ± SEM of three to five independent experiments. D, p38MAPK inhibition does not stimulate TRE-mediated promoter activity. OPCs were cotransfected with AP1Luc and pcDNA3.1 (vector), dominant-negative p38αAGF mutant (DNp38), or pFC-MEK1 (MEK1). *p < 0.05 versus vector and MEK1; one-way ANOVA, Holm–Sidak test. All data represent mean ± SEM of three experiments.

Since MEK inhibition restored myelin gene expression in the presence of p38MAPK inhibition, we wanted to determine whether MEK overexpression alone could repress myelin gene promoter activity. Constitutively active MEK1 that was cotransfected with MBPLuc and CNPLuc significantly repressed promoter activities (Fig. 10B). The inclusion of TAM67, which expresses dominant-negative c-Jun, attenuates the MEK-induced repression of myelin promoter activity (Fig. 10B), indicating that MEK represses myelin gene expression through c-Jun activity. Based on the observation that the inhibition of p38MAPK activity upregulated ERK activity through MEK, we reasoned that TAM67 might also relieve promoter repression resulting from p38MAPKα inhibition. Figure 10C shows that TAM67 significantly relieves the repression of both MBP and CNP promoters by dominant-negative p38MAPKα (DNp38α). With both MEK1 and dominant-negative DNp38α, TAM67 restored MBPLuc activity to control levels while partially alleviating the repression of CNPLuc (Fig. 10, compare B, C). These observations indicate that the regulation of c-Jun activity could play a direct transcriptional role in the developmental control of myelin gene expression by p38MAPK. MEK1 induces the AP1 components of Fra and Jun (Treinies et al., 1999), which stimulates TRE-dependent transcription (Fig. 10D), but interestingly, the elevated level of phosphorylated c-Jun that results from p38MAPK inhibition does not produce similar effects (Fig. 10D). This shows that, distinct from the effects of MEK1, p38MAPK-mediated target modulation does not involve processes that lead to TRE activation. A similar observation was also previously made in keratinocytes (Rosenberger et al., 1999), in which increased FosB and JunD expression by SB203580 failed to activate AP1Luc despite increased activation of ERK and JNK. Because of its departure from conventional AP1 transactivating activity, we have chosen to refer to the p38MAPK-associated c-Jun as an AP1-like activity.

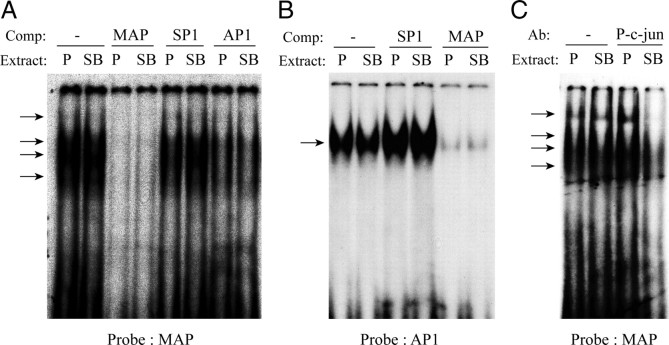

p38MAPK regulates AP1 complex composition and modulates phosphatase levels

To determine whether Jun-mediated AP1-like binding plays a role in mediating the signaling events evoked by the inhibition of p38MAP kinase, EMSAs were performed using a previously identified AP1-like site in the MBP promoter, which we have named MBP AP1 (MAP) (Miskimins and Miskimins, 2001). Deletion of this binding site leads to increased MBP promoter activity, indicating negative regulation by AP1-like proteins in MBP transcription (Miskimins and Miskimins, 2001). This site forms several complexes with nuclear extracts from cultured OPCs treated with PDGF, in the absence and presence of SB203580. Complex formation at this site using control and SB-treated nuclear extracts was completely abolished with excess unlabeled MAP oligonucleotide as competitor, partially competed with a consensus AP1 site (Fig. 11A), and unaffected by an unrelated Sp1 consensus sequence, lending support to its AP1-like nature.

Figure 11.

P-c-Jun is detected on an AP1-like sequence of the MBP promoter after p38MAPK inhibition. Nuclear extracts were prepared from OPCs treated with PDGF(P) or PDGF plus 2 μm SB203580 (SB) for 3 d. A, EMSA showing DNA–protein complex formation on an AP1-like sequence of the MBP promoter (MAP) binds proteins that also recognize the consensus TRE AP1 (AP1). Using the MAP probe, 8 μg of both control and SB203580-treated extracts form complexes (arrows) that are competed by 100-fold excess unlabeled MAP oligonucleotide (MAP), unaffected by excess AP1 oligonucleotide (SP1), or attenuated by TRE AP1 (AP1). B, The MAP sequence effectively abolishes complex formation on the consensus AP1 probe. A single well defined complex (arrow) is formed on the consensus AP1 probe with both OPC nuclear extracts, which is unaffected by 100-fold excess SP1, but is effectively abolished by excess MAP. C, In supershift assays, preincubation of binding reactions with an anti-P-c-Jun antibody reduces complex formation (arrows) on the MAP probe only after p38MAPK inhibition with SB203580 (SB).

Using the consensus AP1 binding sequence as a probe, and with unlabeled MAP as a competitor, however, DNA complex formation is effectively abolished (Fig. 11B), suggesting a difference in the composition between DNA–protein complexes formed on the probes (Fig. 11A,B), possibly with a greater diversity of proteins binding at the MAP site than at the consensus AP1. Supershift assays with the MAP probe in Figure 11C show that preincubation of the binding reactions with an antibody against P-c-Jun abolished DNA-complex formation only in extracts prepared from SB203580-treated OPCs. This indicates that P-c-Jun was recruited to this complex only after the inhibition of p38MAPK activity.

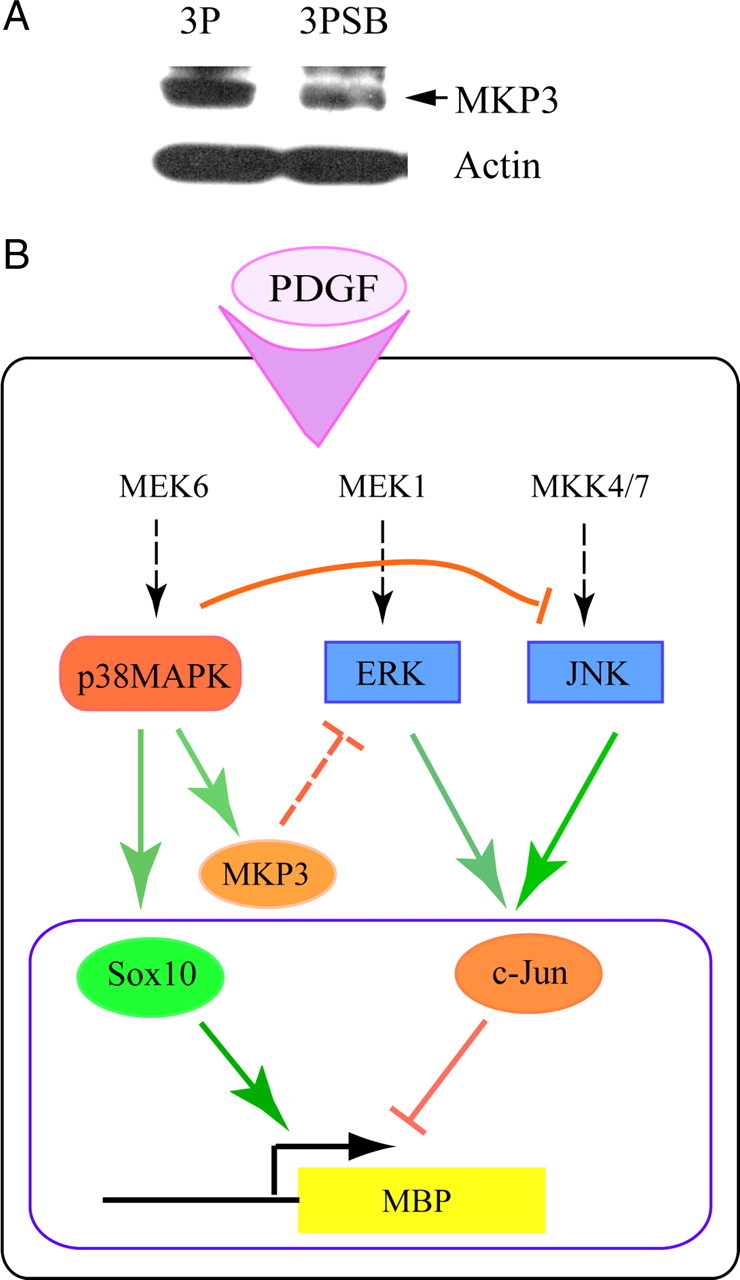

To begin to understand the nature of the p38-ERK/JNK antagonism, we surveyed possible mediators of such kinase cross talk. MAPK activity is regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of Ser and/or Tyr residues located in the kinase domain. The dual specificity phosphatase family (DUSP)/MAPK phosphatases (MKPs) are capable of removing phosphoryl groups from Tyr as well as Ser/Thr residues. MKP3/DUSP6 is highly specific for ERK inactivation (Muda et al., 1996; Arkell et al., 2008), and its genetic ablation results in ERK hyperactivation (Maillet et al., 2008). Furthermore, MKP3 regulation by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Bermudez et al., 2008), whose activity is critical for OPC development (Tyler et al., 2009), makes this phosphatase a candidate mediator in this system. In Figure 12A, p38MAPK inhibition by SB203580 decreased the protein levels of MKP3 in OPCs to 53.1 ± 2.6% of control values, indicating that a specific antagonist of ERK is positively regulated by p38MAPK. Our attempts to detect MKP1 have been unsuccessful, so that other p38MAPK-regulated phosphatases at present cannot be excluded. Nonetheless, these observations support the notion that p38MAPK activity regulates the elevation of c-Jun activity by attenuating ERK and JNK activation during lineage progression. As illustrated in Figure 12B, this event could thus contribute to the de-repression of myelin gene expression through changes in the transcriptional complexes formed on the promoters of myelin genes.

Figure 12.

Possible mechanism of p38MAPK action in OPCs. A, p38MAPK activity supports expression of the dual-specificity phosphatase MKP3/DUSP6. Representative Western blot showing inhibition of p38MAPK activity in cultured OPCs with 2 μm SB203580 for 3 d in the presence of PDGF (3PSB) downregulates the protein levels of MKP3/DUSP6, a phosphatase known to dephosphorylate ERK. B, Hypothetical model of p38MAPK involvement in molecular events that lead to myelin gene regulation. The dashed arrows indicate likely pathways not analyzed in detail in this study. On stimulation with PDGF, p38MAPK, ERK, and JNK are activated. p38MAPK promotes Sox10 DNA binding and transcriptional activity at myelin gene promoters, while at the same time p38MAPK represses ERK and JNK activity. p38MAPK may antagonize ERK activation through its support of MKP3 expression. Modulation of c-Jun activation by ERK and JNK alters the inhibitory effect of c-Jun on myelin gene expression (e.g., MBP). Thus, positive and negative regulators of myelin gene transcription are both modulated by p38MAPK.

Discussion

The study of intracellular signals that regulate myelinogenesis is crucial for our understanding of developmental and pathological processes in white-matter structures. p38MAPK is well established as a mediator of stress responses in neural cells (Kawasaki et al., 1997; Stariha and Kim, 2001b); however, its physiological role(s), including in glial development, have only begun to be characterized (Fragoso et al., 2003, 2007; Bhat et al., 2007; Hamanoue et al., 2007). We have now identified p38MAPK as an important regulator of positive and negative effectors of oligodendrocyte progenitor lineage progression, and revealed an interaction of p38MAP kinase with parallel kinases as contributing pathways in the control of OPC development.

Previous studies have indicated a role for p38MAPK in oligodendrocyte function because an abundance of p38MAPKα was demonstrated in fiber bundles of the corpus callosum and internal capsule. In these structures, selective colocalization of p38MAPKα with the myelin-specific protein CNP, and not axonal neurofilament protein, strongly suggested an association between p38MAPK and myelin function (Maruyama et al., 2000). p38MAPK inhibition reduces myelin gene expression; this is significant only when p38MAPK is inhibited early after mitogen withdrawal (Fragoso et al., 2007), indicating that p38MAPK acts during the transition from progenitor to preoligodendrocyte stage. Our finding that p38MAPK phosphorylation coincides temporally with MBP protein expression in white-matter tissue, and its detection at P11 in CC1+ oligodendrocytes, supports a function in promoting differentiation. However, p38MAPK phosphorylation is still detected in CC1+ cells at later postnatal ages, suggesting additional roles in myelin maintenance in vivo.

Few myelin-specific transcription factors that respond to MAPK activity have been identified. PKA (protein kinase A)-CREB responds to p38MAPK inhibition, suggesting an association between p38MAPK and cAMP-mediated oligodendrocyte differentiation (Bhat et al., 2007). We have demonstrated that MEK6 stimulates Sox enhancer and MBP promoter activity in a p38MAPK-dependent fashion (Fig. 2). To date, several Sox genes, 4, 8, 9, 10, and 17 (Stolt et al., 2004; Sohn et al., 2006; Potzner et al., 2007; Finzsch et al., 2008), are known to regulate oligodendrocyte development. Our observation highlights a role for p38MAPK-mediated Sox10 regulation in terminal differentiation and myelin gene expression. In chondrogenesis, p38MAPK increases Sox9 transcriptional activity without changing its expression, and apparently not by direct phosphorylation of the Sox9 protein (Zhang et al., 2006). Interestingly, we have also observed little effect of p38MAPK activity on Sox10 RNA levels. Although changes in protein levels and/or phosphorylation cannot be excluded, our results are consistent with the current understanding that both p38MAPK and Sox10 coordinately regulate multiple myelin genes, which would ultimately impact differentiation and myelination (Stolt et al., 2002; Fragoso et al., 2007).

In Schwann cells, ERK drives dedifferentiation (Harrisingh et al., 2004) and opposes Akt-mediated myelination (Ogata et al., 2004). Although p38MAPK positively regulates myelination in both Schwann cells (Fragoso et al., 2003) and oligodendrocytes (Fragoso et al., 2007; Haines et al., 2008), a functional relationship between ERK/JNK and p38MAPK in OPC development has not previously been established. A role for ERK in OPC differentiation was implicated by Horiuchi et al., whose studies with IFN-γ (interferon-γ) revealed an inhibitory effect of ERK on OPC survival (Horiuchi et al., 2006). Cytokines are known to activate ERK (Chang et al., 2003; Fei et al., 2008; Sobota et al., 2008), so it is possible that cytokine-induced MAP kinase dysregulation interferes with OPC differentiation (Agresti et al., 1996; Lin et al., 2004; Chew et al., 2005). By establishing ERK as one of the targets of p38MAPK that negatively regulates myelin synthesis, our results offer clues to the developmental importance of controlling ERK activity. p38MAPK is not the only pathway to be antagonized by ERK, as the PI3-kinase/Akt phosphorylation is de-repressed by MEK inhibitors in NIH3T3 cells (Hayashi et al., 2008). Thus MEK inhibition in OPCs may affect other pathways, such as Akt/mTOR (Tyler et al., 2009), which regulate oligodendrocyte development. Functional cross talk between p38MAPK and ERK has been found in other systems (Xia et al., 1995; Lavoie et al., 1996), and the phosphatases mediating such cross talk are of great interest. In human fibroblasts, p38MAPK downregulates Ras signaling (Chen et al., 2000) by a process that may involve Ser/Thr protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A (Westermarck et al., 2001). In OPCs, the dual specificity MAPK phosphatase MKP3/DUSP3, which dephosphorylates ERK, was decreased after p38MAPK inhibition (Fig. 12A), but MKP-1, PP1, and PP2A remain possible mediators of cross talk (Kim et al., 2004, 2008; Cheng et al., 2009), so that cross talk mechanisms involving ERK1/2 in OPCs are not yet fully defined.

p38MAPK may regulate JNK by several pathways. SB202190 and SB203580 can activate JNK by stimulating MLK-3-MEK4/MEK7 (Muniyappa and Das, 2008). Alternatively, JNK1 may be activated directly downstream of ERK2 (Browaeys-Poly et al., 2005). The genetic ablation of p38MAPKα/MAPK14 (Hui et al., 2007) results in increased JNK activity and cell proliferation. In these mutant mice, increases in c-Jun, cyclin D1, and cdc2 were also observed (Hui et al., 2007). In the oligodendrocyte lineage, p38MAPK inhibition prevents the morphological differentiation of OPCs (Bhat et al., 2007), without affecting BrdU incorporation or expression of cell cycle checkpoint regulators (Fig. 1G; supplemental Fig. 1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). This apparent uncoupling of proliferation and differentiation suggests that cell cycle changes in OPCs are unlikely to directly mediate the differentiation functions of p38MAPK.

p38MAPKα inhibits Ras oncogenic activity (Bulavin et al., 2002, 2004; Qi et al., 2004), and both ERK and JNK are known to be essential for Ras mitogenic signaling through fos and jun (Westwick et al., 1994; Clark et al., 1997). Our observations of increased ERK and JNK activity in OPCs on p38MAPK inhibition suggest Ras involvement. The coordinate control of ERK and JNK is also observed in the stimulation of neurite outgrowth after injury (Waetzig and Herdegen, 2005) and during neural differentiation of PC12 (Zentrich et al., 2002). Studies in other systems suggest that, in addition to Ras, protein kinase C (Sriraman et al., 2008) and MEKK1 (Xia et al., 2000; Waetzig and Herdegen, 2005) are also possible upstream activators of c-Jun. Functional relationships between these kinases and p38 have yet to be elucidated in OPCs.

Our experiments show that p38MAPK control of MEK and JNK activity converges on c-Jun phosphorylation. c-Jun overexpression negatively regulates myelin gene promoter activity in OPCs (Fig. 10A). Furthermore, overexpression of MEK1 and DNp38α and coexpression with TAM67 (Fig. 10B,C) indicate that, in OPCs, c-Jun has a negative regulatory role in myelin gene transcription. These findings are in agreement with studies showing JNK and c-Jun-mediated inhibition of Krox20/egr2 expression and subsequent myelination (Parkinson et al., 2004, 2008; Jessen and Mirsky, 2008). Sox10 has been shown to interact with c-Jun and to attenuate AP1 activation (Wissmüller et al., 2006). This property of Sox10 could contribute to the control of myelin gene expression, suggesting that Sox10 function may help sequester P-c-Jun, preventing its recruitment into inhibitory DNA binding complexes. It remains possible that, through both genomic and nongenomic actions of Sox10, the effects of p38MAPK would be reinforced at myelin gene promoters that are responsive to both Sox10 and AP1.

The role of c-Jun/AP1 in the regulation of myelin gene expression in oligodendrocyte lineage cells is poorly understood. OPCs have previously been shown to lack conventional Fos/Jun AP1 complexes, but instead form atypical APprog complexes on a GFAP-derived AP1 site that declined with progenitor differentiation (Barnett et al., 1995). Our studies of DNA–protein complexes and AP1Luc reporter assays reveal the atypical nature of p38MAPK-associated AP1 activity in OPCs. An inhibitory role for the AP1-like site in the MBP promoter was previously demonstrated when its deletion increased the response of the MBP promoter to differentiating stimuli (Miskimins and Miskimins, 2001). The complex formed on this site under normal growth conditions lacked c-Jun (Miskimins and Miskimins, 2001). In our studies, we found that the nuclear proteins that bound this AP1-like site also lacked c-Jun under conditions that favored MBP expression. Although the composition of the MBP complex is presently unknown, there may be overlap between proteins binding the MBP AP1 site and the consensus AP1/TRE site (Fig. 11A,B), because excess AP1/TRE partially reduced complex formation on the MBP AP1. Notably, the MBP AP1-like site only recruited P-c-Jun when p38MAPK was inhibited, suggesting that changes in the composition of DNA-binding factors could regulate myelin gene promoter activity.

In conclusion, our findings, summarized in Figure 12B, support an important role for p38MAPK activity in oligodendrocyte development and reveal molecular targets through which p38MAPK affects oligodendrocyte differentiation. Protein kinases are under investigation as therapeutic targets in a variety of CNS disorders (Chico et al., 2009), and strategies applying MAP kinase modulation may be helpful in demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis. Indeed, inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway has been shown to improve the survival of cultured OPCs exposed to cytotoxic levels of proinflammatory cytokines (Horiuchi et al., 2006), supporting the value of kinase-based approaches. An understanding of MAPK targets and their interactions in developmental regulation of oligodendrocyte lineage progression and myelination is vital to successful therapeutic intervention in disease.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the European Leukodystrophies Association (V.G.), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01 NS056427 (V.G.), and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society Grant RG3954A1/2 (L.-J.C.). We are grateful to Dr. Sergio Schinelli for critical and insightful comments and discussion, to Drs. Roger Davis and Michael Birrer for gifts of expression plasmids, and to Alina Hoehn for technical support.

References

- Agresti C, D'Urso D, Levi G. Reversible inhibitory effects of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha on oligodendroglial lineage cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1106–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Estrada Y, Liu D, Ossowski L. ERK-MAPK activity as a determinant of tumor growth and dormancy; regulation by p38-SAPK. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1684–1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Ossowski L, Rosenbaum SK. Green fluorescent protein tagging of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 pathways reveals novel dynamics of pathway activation during primary and metastatic growth. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7336–7345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkell RS, Dickinson RJ, Squires M, Hayat S, Keyse SM, Cook SJ. DUSP6/MKP3 inactivates ERK1/2 but fails to bind and inactivate ERK5. Cell Signal. 2008;20:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong RC, Le TQ, Frost EE, Borke RC, Vana AC. Absence of fibroblast growth factor 2 promotes oligodendroglial repopulation of demyelinated white matter. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8574–8585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08574.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, Shpiro N, Hastie CJ, McLauchlan H, Klevernic I, Arthur JS, Alessi DR, Cohen P. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SC, Rosario M, Doyle A, Kilbey A, Lovatt A, Gillespie DA. Differential regulation of AP-1 and novel TRE-specific DNA-binding complexes during differentiation of oligodendrocyte-type-2-astrocyte (O-2A) progenitor cells. Development. 1995;121:3969–3977. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron W, Metz B, Bansal R, Hoekstra D, de Vries H. PDGF and FGF-2 signaling in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells: regulation of proliferation and differentiation by multiple intracellular signaling pathways. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:314–329. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez O, Marchetti S, Pagès G, Gimond C. Post-translational regulation of the ERK phosphatase DUSP6/MKP3 by the mTOR pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27:3685–3691. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat NR, Zhang P, Mohanty SB. p38 MAP kinase regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation with CREB as a potential target. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Peirano RI, Rossner M, Nave KA, Birchmeier C, Wegner M. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browaeys-Poly E, Fafeur V, Vilain JP, Cailliau K. ERK2 is required for FGF1-induced JNK1 phosphorylation in Xenopus oocyte expressing FGF receptor 1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1743:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulavin DV, Demidov ON, Saito S, Kauraniemi P, Phillips C, Amundson SA, Ambrosino C, Sauter G, Nebreda AR, Anderson CW, Kallioniemi A, Fornace AJ, Jr, Appella E. Amplification of PPM1D in human tumors abrogates p53 tumor suppressor activity. Nat Genet. 2002;31:210–215. doi: 10.1038/ng894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]