Abstract

The escalating costs associated with antimicrobial chemotherapy have become of increasing concern to physicians, pharmacists and patients alike. A number of strategies have been developed to address this problem. This article focuses specifically on sequential antibiotic therapy (sat), which is the strategy of converting patients from intravenous to oral medication regardless of whether the same or a different class of drug is used. Advantages of sat include economic benefits, patient benefits and benefits to the health care provider. Potential disadvantages are cost to the consumer and the risk of therapeutic failure. A critical review of the published literature shows that evidence from randomized controlled trials supports the role of sat. However, it is also clear that further studies are necessary to determine the optimal time for intravenous to oral changeover and to identify the variables that may interfere with the use of oral drugs. Procedures necessary for the implementation of a sat program in the hospital setting are also discussed.

Keywords: Cost effectiveness, Intravenous antibiotic therapy, Oral antibiotic therapy, Quality of life, Sequential antibiotic therapy

RÉSUMÉ :

Les coûts sans cesse croissants associés à l’antibiothérapie inquiètent de plus en plus les médecins, les pharmaciens et les patients. Certaines stratégies ont été mises au point pour répondre à ce problème. Le présent article s’attarde plus précisément au traitement antibiotique séquentiel, une stratégie par laquelle les patients passent de la forme intraveineuse à la forme orale d’un médicament, qu’il s’agisse ou non de produits d’une même classe. Parmi les avantages de l’antibiothérapie séquentielle, notons l’aspect économique et la commodité pour le patient et pour le personnel soignant. Les désavantages potentiels sont les coûts assumés par le consommateur et le risque d’échec thérapeutique. Une analyse critique de la littérature publiée révèle que les données tirées d’essais contrôlés randomisés appuient l’antibiothérapie séquentielle. Toutefois, il faut de toute évidence poursuivre les études afin de déterminer le moment idéal du passage de la forme intraveineuse à la forme orale et d’identifier les variables qui peuvent interférer avec l’emploi des médicaments par voie orale. Les étapes nécessaires à l’application d’un programme d’antibiothérapie séquentielle dans le contexte hospitalier sont également décrites.

Over the past two decades, our therapeutic armamentarium has been greatly expanded with agents that provide excellent antimicrobial activity combined with improved pharmacokinetic features and improved adverse effect profiles. At the same time, however, economic constraints and hospital bed closures have forced us to consider approaches other than traditional in-hospital intravenous antibiotic use. We now have a number of options that facilitate and simplify patient care and reduce costs. These include home intravenous therapy and oral therapy using agents that do not compromise therapeutic efficacy.

This paper reviews some of the economic issues associated with antimicrobial therapy and examines the treatment of infections with intravenous antimicrobials and the subsequent use of oral agents. This practice is referred to as sequential antibiotic therapy (sat); simply stated, it is the practice of changing from intravenous to oral dosage forms as early during a course of antibiotic treatment of infection as is clinically possible.

COST CONTAINMENT ISSUES

Antibiotics are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in Canada. According to the Fifth Annual Report of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (1), total Canadian patented prescription drug revenue was over $2 billion in 1992. Anti-infective agents, costing $354 million, accounted for the largest number of patented drug products sold in Canada. The cost of injectable antibiotics alone was $110 million (2). In any Canadian hospital, antibiotics often represent the single largest component of the hospital pharmacy budget, accounting for 20 to 40% of total drug costs.

In an attempt to cope with increasing costs, several strategies have been developed and implemented and may be classified as ‘educative and persuasive’, ‘facilitative’ and ‘restrictive’ strategies (3). The following list includes most of these:

prescriber education

formulary restriction and reserved antimicrobial program

selective reporting of susceptibility testing

automatic stop policies

therapeutic interchange programs

antimicrobial order forms

required consultation and physician or service restriction

sat (3).

It is beyond the scope of this article to deal with all these cost containment strategies; our purpose is to focus specifically on sat.

SEQUENTIAL ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

sat refers to the practice of limiting the use of intravenous antibiotics to the early stages of infection and then converting to oral agents for the duration of treatment.

sat is not as new an approach to cost effective antibiotic prescribing as one might think. Studies published in the 1970s involving children with osteomyelitis and septic arthritis demonstrated the efficacy and safety of initial treatment with parenteral antibiotics followed by conversion to oral agents as soon as the acute signs and symptoms of infection were controlled (4–8).

In a 1991 survey of antibiotic decision making at a 1000-bed tertiary care hospital, Quintiliani et al (9) reported that antibiotic therapy could be ‘streamlined’ in approximately 75% of patients in one of three ways: first, by changing from combination therapy to monotherapy; second, by changing to another agent with a narrower antimicrobial spectrum of activity and/or to one with preferable pharmacokinetics; and third, by changing the route of administration from intravenous to intramuscular or oral.

This concept of streamlining from a more complex, often more expensive, regimen to a less complex one has also been referred to in the literature as ‘stepdown therapy’, ‘switching’ or ‘sequential therapy’. However, these terms have not always been used synonymously.

For example, stepdown therapy and switching have been used to denote not only a change from intravenous to the oral form of the same drug, but also a change to a different drug once the conversion to oral therapy has been made (10,11). Likewise, sequential therapy has been used to denote a change from intravenous to oral forms of the same drug or different drugs (12,13). Streamlining has also been used to denote the change from combination therapy to monotherapy (14). It might, therefore, avoid confusion by establishing a common terminology for describing conversion from intravenous to oral medications. Not only would this make discussion of such treatment strategies easier, it would aid in cataloguing the medical literature dealing with this subject. We propose that the term ‘sequencing’ or ‘sequential antibiotic therapy’ be used to define the strategy of converting patients from intravenous to oral medications, regardless of whether the same or a different class of drug is used.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF SAT

There are sound clinical and financial reasons to pursue a therapeutic strategy that incorporates appropriate early conversion from intravenous to oral antimicrobials. Some physicians remain reluctant to do this, perhaps because of a lack of knowledge and appreciation of the efficacy and advantages of such a strategy, as well as the sense of security provided by the serum and tissue drug levels obtained using intravenous drugs. This reluctance has, unfortunately, fostered the unnecessarily prolonged use of intravenous medications in the hospital setting for treatment of infections that could benefit from a shortened course of intravenous treatment followed by oral therapy.

Advantages of SAT:

Three main benefits are associated with the use of sat: economic benefits, patient benefits and benefits to the health care provider.

Economic benefits:

With any drug, there are two costs to consider: the more obvious or apparent cost of the agent, referred to as the acquisition cost, and the secondary costs related to delivery or administration of the drug. The latter include a variety of factors, such as a pharmacist’s preparation and delivery time; a nurse’s administration time; ancillary supplies, such as intravenous bags and tubing; loss due to wastage; and the need for laboratory monitoring of drug serum levels, as is required with aminoglycosides and vancomycin. All these factors contribute to the cost of drug therapy and should be considered when the cost of a particular drug is evaluated.

Preparation and administration costs vary among hospitals. Rush (15) reported that the cost of preparation and administration added us$7.00 to the cost of each dose of intravenous antibiotic. In Australia, such costs add between aus$4.55 and $10.58 to the cost of each intravenous dose (16). Others have reported that, by simply replacing one intravenous antibiotic with another that is given less frequently, substantial cost savings are realized, even when the acquisition cost of the replacement drug is higher (17,18). For example, at one American hospital, the total daily administration cost of penicillin G 3×106 U given intravenously every 4 h is us$29.26 (17), yet the cost of cefazolin 1 g intravenously every 8 h is only us$14.60.

Generally, acquisition costs for the intravenous form of a drug are greater than those of the oral form. Some examples of these comparative costs are given in Table 1. The use of oral agents obviates the need for most, if not all, ancillary costs.

TABLE 1.

Acquisition cost of one dose of commonly prescribed antibiotics*

| Drug | Dose (route) | Acquisition cost ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 1–2 g (IV) | 0.70–1.40 |

| Amoxicillin | 500 mg (PO) | 0.08 |

| Cefuroxime | 750 mg–1.5 g (IV) | 6.93–12.29 |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 500 mg (PO) | 2.60 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 400 mg (IV) | 33.00 |

| 250–750 mg (PO) | 2.22–4.73 | |

| Clindamycin | 600 mg (IV) | 12.86 |

| 300–450 mg (PO) | 1.58–2.38 | |

| Metronidazole | 500 mg (IV) | 1.49 |

| 500 mg (PO) | 0.04 | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 160 mg/800 mg (IV) | 3.20 |

| 160 mg/800 mg (PO) | 0.04 |

Prices supplied by purchasing department, Henderson General Division, Hamilton Civic Hospitals, Hamilton, Ontario, December 1993. IV Intravenous; PO Oral

At the Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre, an intravenous to oral antibiotic conversion program has been in place since 1987. Changing from intravenous to oral therapy using drugs such as metronidazole, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, fluconazole, cefuroxime and cefixime has resulted in savings of at least $30,000 yearly (10,11). Hartford Hospital in Connecticut projected an annual saving of us$107,637 based on an antibiotic streamlining program (14).

Another major financial saving is realized by the earlier discharge of the patient from the hospital. This eliminates the expenses associated with housing a patient in an acute care facility solely for the purpose of administering intravenous antibiotics (19).

The magnitude of cost savings that can accrue by sequencing from intravenous to oral treatment is apparent from a multicentre study in the United States involving 766 hospitalized patients. After successful conversion to oral ciprofloxacin from a variety of parenteral antimicrobial agents, 418 patients were discharged from the hospital earlier than would have otherwise occurred. An estimated total of 2266 hospital days were saved, resulting in savings of us$793,100. Projected savings for total drug plus hospitalization costs were us$980,246 (20).

Patient benefits:

Although less quantifiable than the more tangible financial gains, patient-related benefits are nevertheless real and important. In hospital, the use of oral instead of intravenous drugs increases patient comfort and mobility, the latter being a particularly important consideration in the elderly. By not using intravenous lines, there is less risk of phlebitis and line-related infections. The earlier discharge from hospital also decreases the risk of development of other no-socomial infections. An earlier return to family and, possibly, to work provides benefits in terms of enhanced quality of life as well as possible economic benefits.

Health care provider benefits:

Considerable time is spent by pharmacists and nurses in preparing and administering intravenous antibiotics. Use of sat decreases the amount of personnel time associated with drug delivery and, although the actual benefits of ‘saved time’ are difficult to assess, it may serve to free the individual for other tasks that may improve patient care and enhance job satisfaction for the health care provider.

Disadvantages of SAT:

There are two perceived disadvantages with sat: economic and risk of therapeutic failure.

Economic disadvantages:

While receiving medication in the hospital, the patient is not responsible for any of the drug-related costs. However, once discharged, the consumer must bear the cost of therapy. It is therefore important to discuss the cost of therapy with the patient before discharge.

Risk of therapeutic failure:

Patient compliance with treatment while in the hospital is taken for granted. However, once outside the hospital this becomes much more difficult to ensure. Poor compliance with the planned oral treatment regimen could result in treatment failure or relapse of infection. Readmission of the patient to the hospital would quickly offset any cost savings realized by a change to oral therapy.

Another potential problem is that incomplete or inadequate treatment of infection may contribute to the development of microbial resistance, making it necessary to use more expensive or possibly more toxic agents to treat infection.

In a study that specifically examined patient compliance with an oral regimen, Paladino et al (21) documented an 81% compliance rate in out-patients taking ciprofloxacin twice daily following initial treatment with intravenous antibiotics in hospital. Therapeutic outcomes in this group were excellent despite compliance rates of less than 100%. Compliance rates were also examined by Cramer et al (22), who showed results identical to those described by Paladino et al for twice-daily dosing, while slightly higher compliance rates were seen when medication was given once daily (87%). When dosage frequency was increased to four times a day, compliance rates dropped dramatically, ie, from 87% to 39%.

Even if the patient is compliant, therapeutic failures may still occur because of drug interactions that decrease the bioavailability of oral antibiotics. It is important that all prescription medications be reviewed with the patient at the time of discharge from hospital to ensure that no untoward drug interactions occur while the antibiotics are being taken at home. It is also important to review the use of any nonprescription agents. For example, antacids have been shown to reduce the absorption of oral quinolones, tetracycline, metronidazole and cefpodoxime proxetil; thus, patients should be advised to separate antacid use from ingestion of these antibiotics by at least 2 h (23). The use of oral iron preparations should also be avoided in patients being treated with quinolones and tetracyclines because iron decreases the absorption of these drugs (24). Ingestion of milk and other dairy products can also interfere with the absorption of oral tetracycline and, to a lesser extent, of quinolones (25).

CRITERIA FOR SELECTION OF PATIENTS AND DRUGS FOR SAT

Physicians have always been more comfortable using parenteral rather than oral drugs when treating serious infection, owing to concerns about drug absorption, bioavailability, and serum and tissue levels when oral agents are used. In the selection of patients for conversion to oral therapy, several criteria should be fulfilled: the patient should be hemodynamically stable, able to ingest and swallow oral drugs and should have a functioning gastrointestinal tract. Yet, although oral antimicrobial activity can often be considered as early as three days after initiation of intravenous therapy in stable patients, some individuals are not given oral therapy until they are discharged, ie, usually after at least seven days of intravenous treatment.

There are numerous reports in the literature of the successful use of intravenous followed by oral antibiotics for treatment of serious infections. Many involve intravenous to oral sequencing within the same class of drugs, while some involve a change in drug class. Among the conditions treated with sat are pneumonia (both community and hospital acquired), pyelonephritis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and skin and skin structure infections.

If the above criteria are fulfilled, the next step is to select the antimicrobial that is most appropriate. The main therapeutic objective in changing from intravenous to oral therapy is to obtain serum and tissue antimicrobial activity that is comparable with that obtained with the intravenous formulation (26,27). Many oral agents have bioavailabilities that are similar to those of their parenteral forms. These include such drugs as metronidazole, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, fluconazole and ciprofloxacin (10,28–32). Several of these drugs have virtually equivalent bioavailability whether given intravenously or orally.

Use of these drugs as part of a sequential therapy regimen can help to alleviate the physician’s concerns about suboptimal drug concentrations when the switch to oral therapy is made, because it is generally accepted that these oral agents provide adequate therapeutic efficacy (10,11,27). Some antibiotics with oral bioavailabilities lower than those of their intravenous formulations have nevertheless been useful in sequential therapy. Such is the case for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin and cefuroxime axetil (9,10, 33).

Much has been written about the pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral ciprofloxacin supporting the use of the oral form in intravenous to oral sequencing (30,31,34,35). For example, with an average unimpeded bioavailability of 75% (in the absence of substances that interfere with absorption), an oral dose of 500 mg ciprofloxacin provides an amount of drug equivalent (ie, statistically similar to the area under the curve) to that obtained with a 400 mg intravenous dose (36).

Other quinolones, such as ofloxacin (not available parenterally in Canada), also have nearly identical pharmacokinetic characteristics when given intravenously and orally, and all quinolones appear to have high volumes of distribution and relatively low protein binding (31). Most quinolones attain tissue concentrations that exceed the minimal inhibitory concentration values of the common aerobic pathogens (37).

When selecting an oral agent, the physician should take into account a number of factors including bioavailability, clinical efficacy, tolerability and cost.

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING SAT

Rules of scientific evidence that can be used to assess published data have been developed and published as part of a series of clinical epidemiology rounds (38). Six criteria are used to assess articles and to determine the validity and applicability of the results. These are:

Was the assignment of patients to treatment truly randomized?

Were all clinically relevant outcomes reported?

Were the study patients recognizably similar to your own?

Were both statistical and clinical significance considered?

Is the therapeutic manoeuvre feasible in your practice?

Were all patients who entered the study accounted for at its conclusion?

A literature search revealed 32 published studies of infections treated using sat. Of these, 13 were randomized controlled trials and 19 were nonrandomized. These studies are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Randomized controlled trials of sequential antibiotic therapy for treatment of infection

|

Author (reference), Number of participants Type of infection |

Mean age (years) | Regimen and dosages | Duration of therapy (days) | Overall efficacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical* (%) | Bacterial eradication (%) | ||||||||

| Kalager et al (39), n=281 septicemia, LRTI, UTI, GI | 61 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg bid |

5.8 IV | → | 6.4 oral | 84 | 61 |

| 65 | vs Ceftazidime/tobramycin IV 1.5 g q 8h based on levels | 9.5 IV | 84 | 66 | |||||

| Dominguez et al (40), n=39 skin, soft tissue | 49.9 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500 mg q 12h |

4 IV | → | 12 oral | 95 | |

| 53.3 | vs Ceftazidime IV 1 g q8h | 9 IV | 80 | ||||||

| Gaut et al (43), n=32 bone & joint, intra-abdominal, RTI, UTI, SST, wound, bacteremia | 66 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500 mg q 12h |

Minimum 2 days IV | 82 | 53.8 | ||

| vs Ceftazidime IV 1–1.5 g q8–12h | 16 IV | 72 | 55.5 | ||||||

| Fass et al (44), n=52 LRTI, UTI, SST, endocarditis, sepsis, mastoiditis | 46 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q l2 h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500–750 mg q 12h |

3–6 IV | → | 13–16 oral | 81 | |

| vs Ceftazidime IV 1–2 g q8–12h | 13.5 IV | 71 | |||||||

| Cox (41), n=77 complicated UTI | 61 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500 mg q 12h |

4 IV | → | 6 oral | 100 | 100 |

| 68 | vs Ceftazidime IV 500 mg q 8h | 9 IV | 97 | 87 | |||||

| Hirata-Dulas et al (47), n=50 nursing home acquired LRTI | 79.3 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

3.4 IV | → | 10.6 oral | 50 | |

| 79.4 | vs Ceftriaxone IV 2 g | → | Ceftriaxone IM 1 g | 3.9 IV | → | 10.1 IM | 54 | ||

| Khan and Basir (48), n=122 lower RTI | 58 overall (not differentiated by treatment arm) | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500 mg q 12h |

6 IV | → | 5 oral | 91 | |

| vs Ceftazidime IV 1–2 g tid | → | Various oral antibiotics | 7 IV | → | ? | 89 | |||

| Menon et al (49), n=37 pneumonia | 32 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

Minimum 2 days IV | 100 | |||

| 38 | vs Ceftazidime IV 1–2 g q8h | → | Appropriate oral antibiotics | Minimum 2 days IV | 95 | ||||

| Peacock et al (50), n=39 UTI, LRTI, bone, joint, skin, soft tissue, gall bladder, bacteremia | 58 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500 mg q 12h |

7.4 IV | → | 17†oral | 76 | |

| 55 | vs Ceftazidime IV 1–2 g q 8h | → | Appropriate oral antibiotics | 9.9 IV | → | 12‡ oral | 82 | ||

| Gangji et al (42), n=65 | 66 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h | 3 IV | 97.2 | 94 | ||||

| Gram-negative septicemia | 62 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

7–11 IV | 7–11 oral | 93.1 | 96 | ||

| Feist (51), n=92 LRTI | 63 | Ofloxacin IV 200 mg bid |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 200 mg bid, tid or qid |

Minimum 3 days IV | → | 4–7 oral | 100 overall | 95 |

| vs Amoxicillin/clavulin IV 2.2 g bid-tid |

→ | Amoxicillin/clavulin oral 625 mg bid-tid or qid |

Minimum 3 days IV | → | 4–7 oral | 94 | 82 | ||

| Khajotia et al (52), n=92 LRTI | 63 | Ofloxacin IV 200 mg bid |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 200 mg bid, tid or qid |

Minimum 3 days IV | → | 4–7 oral | 100 overall | 95 |

| vs Amoxicillin/clavulin IV 2.2 g bid-tid |

→ | Amoxicillin/clavulin oral 625 mg bid-tid or qid |

Minimum 3 days IV | → | 4–7 oral | 94 | 82 | ||

| Johnson et al (53), n=85 pyelonephritis | 25 | Ampicillin + gentamicin IV 1 g q 6h/IV q 8h |

→ | Ampicillin oral 500 mg qid |

Minimum 3 days IV | → | 11 days oral | 98 | 89 |

| vs TMP/SMX IV | → | TMP-SMX oral | Minimum 3 days IV | → | 11 days oral | 100 | 91 | ||

| 160 mg/800 mg q 12h +gentamicin IV q 8h | → | 160 mg/800 mg bid | |||||||

Includes cured and improved:

63% of ciprofloxacin patients given additional 17 days oral ciprofloxacin;

55% of ceftazidime patients given additional 12 days oral antibiotics. GI Gastrointestinal; IM Intramuscular; IV Intravenous: LRTI Lower respiratory tract infection; RTI Respiratory tract infection; SST Skin and soft tissue; TMP-SMX Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; UTI Urinary tract infection

TABLE 3.

Nonrandomized studies of sequential antibiotic therapy for treatment of infection

|

Author (reference), Number of participants Type of infection |

Mean age (years) | Regimen and dosages | Duration of therapy (days) | Overall efficacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical* (%) | Bacterial eradication (%) | ||||||||

| Daly et al (12), n=32 SST, osteomyelitis, pneumonia, UTI, peritonitis, bacteremia |

61 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–400 mg q8–12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500–1000 mg q 12h |

5 IV | → | 17.5 oral | 94 | 77 |

| Chrysanthopoulos et al (52), n=169 pneumonia, biliary sepsis, complicated UTI | 62 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q8–12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500–750 mg q 12h |

3.7 IV | → | 5.5 oral | 96 | |

| Bouza et al (55), n=68 UTI, RTI, intra-abdominal, SST, bone or joint, bacteremia |

53.5 | Ciprofloxacin IV 100–200 mg q 12h or Ciprofloxacin oral 500–750 mg q 12h or |

13.3 IV 11.8 oral |

94 overall | 93 | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin IV 100–200 mg q 12h → Oral 500–700 mg q 12h | 11.9 IV | → | 10.4 oral | ||||||

| Chayakul et al (56), n=19 1° bacteremia, meningitis, intra-abdominal abscess, peritonitis, pneumonia, UTI |

32 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 500 mg q 12h |

6 IV | → | 7.5 oral | 85 | 90 |

| Dworkin et al (57), n=10 right-sided Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in IV drug users | – | Ciprofloxacin 300 mg q 2h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

7 IV | → | 21 oral | 100 | 100 |

| Neu et al (58), n=60 endocarditis, osteomyelitis, RTI, UTI, SST | – | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q 12h | 10 IV | 85 overall | 70 overall | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q 12h |

Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

18 IV | 80 oral | ||||||

| Scully et al (59), n=28 osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, SST, pneumonia, UTI | 55 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q 12h | 10 IV | 87 overall | 70 overall | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin IV 200–300 mg q 12h |

Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

19 IV | 37 oral | ||||||

| Giamarellou et al (60), n=54 pneumonia, intra-abdominal abscess, liver abscess, SST, UTI, osteomyelitis, malignant otitis externa | 53.2 | Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h | IV only: 14.9 oral: 10.6 |

91 overall | 61.1 | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin IV 200 mg q 12h |

→ | Ciprofloxacin oral 750 mg q 12h |

|||||||

| Gentry et al (61), n=100 pneumonia | 57 | Ofloxacin IV 400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 400 mg q 12h |

5.7 IV | → | 6.9 oral | 95 | |

| Auten et al (62), n=32 skin, soft tissue | 59 | Ofloxacin IV 400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 400 mg q 12h |

3.9 IV | → | 8.1 oral | 94 | |

| Soper et al (63), n=36 salpingitis | 25 | Ofloxacin IV 400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 400 mg q 12h |

Minimum 3 days IV | → | 7–11 days oral | 100 | |

| Heppt et al (64), n=61 otitis externa and otitis media | 43 | Ofloxacin IV 400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 400 mg q 12h |

1 IV | → | 7 oral | 82 | 80 |

| Lentino et al (65), n=21 skin, soft tissue | 65 | Ofloxacin IV 400 mg q 12h |

→ | Ofloxacin oral 400 mg q 12h |

Minimum 3 IV | → | 5–14 oral | 86 | |

| Gelfand et al (66), n=32 complicated UTI | 68 | Fleroxacin IV 400 mg q 24h |

→ | Fleroxacin oral 400 mg q 24h |

3.2 IV | → | 5.3 oral | 91 | 81 |

| Tetzlaff et al (6), n=30 osteomyelitis, septic arthritis | Pediatric age group | IV: methicillin 200 mg/kg q6h, cefazolin 60 mg/kg q6h, chloramphenicol 100 mg/kg q6h, ampicillin 100 mg/kg q6h | Osteomyelitis: | 93 | |||||

| 7.3 IV | → | 19.8 oral | |||||||

| Oral: cephalexin 100 mg/kg, penicillin V 100 mg/kg. ampicillin 100 mg/kg, cloxacillin 50 mg/kg | Septic arthritis: | ||||||||

| 1.9 IV | → | 17,9 oral | |||||||

| Nelson etal (13), n=75 suppurative skeletal infections | ? pediatric age group | Cefamandole 25 mg/kg q6h IV or Cefuroxime 25 mg/kg q8h IV |

5.8 | → | 14 oral | ? | ? | ||

| ↓ | |||||||||

| Cefaclor 150 mg/kg/day oral or Cephalexin 100 mg/kg/day oral |

|||||||||

| Aronoff et al (67), n=9 osteomyelitis, septic arthritis | 7.7 | Ampiciliin IV/sulbactam IV 50 mg/kg q6h/12.5 mg/kg q6h |

7.1 IV | → | 25.9 oral | 100 | |||

| ↓ | |||||||||

| Ampicillin/sulbactam 25 mg/kg q6h oral | |||||||||

| Schaad et al (68), n=71 peritonsillar abscess, RTI, mastoiditis, SST, UTI | Pediatric age group | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 110–220 mg/kg/day divided into 4 doses IV | 4.6 IV | → | 7.2 oral | 100 | |||

| ↓ | |||||||||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 50–100 mg/kg/day divided into 3 doses oral | |||||||||

| Buchi et al (69), n=24 RTI, SST, UTI, PID, bacteremia |

– | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1.2–2.2 g IV tid-qid | ? IV | 97 | 94 | ||||

| ↓ | |||||||||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 375–625 mg oral tid-qid | 7.9 IV | 7.8 oral | |||||||

IV Intravenous; PID Pelvic infalmmatory disease; RTI Respiratory tract infection; SST Skin and soft tissue; UTI Urinary tract infection

The rules of evidence “constitute applied common sense and are designed to maximize the efficiency as well as the accuracy” of one’s journal reading (38). With this in mind, the articles were first stratified into those that would be subjected to the rules of evidence and those that would not. Since the critical issue is whether sat would perform as well as standard therapy, the standard, or control arm of a comparative study, ideally should consist of intravenous therapy. If both the experimental and control arms use sat, the issue is confounded. Also, since the random assignment of patients minimizes much of the bias associated with nonrandomized clinical trials, use of a randomized control design is essential. Of the 32 papers, only six meet these criteria (Table 4). The rest are either randomized controlled trials, but with inappropriate control arms, or are nonrandomized trials.

TABLE 4.

Clinical trials complying with rules of scientific evidence

| Author (reference) | Randomized controlled trial | Study patients similar to your own | Consideration of issues | Manoeuvre feasible in your practice | All patients accounted for | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | Clinical | |||||

| Kalager et al (37) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dominguez et al (38) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gaut et al (41) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fass et al (42) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cox (39) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gangji et al (40) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

For the purposes of this paper, clinically relevant outcomes were success versus failure of clinical response. Success included both cure and improvement. Bacteriological response per se was not considered as important and was viewed as a surrogate marker. Statistical significance has no bearing on whether the result is important, but simply refers to the likelihood that a particular result was obtained by chance. Consideration of statistical issues took into account whether statistical tests were done and, if so, whether a difference was found that was associated with P<0.05 or, if not statistically significant, whether the sample size was large enough to rule out a type II error.

Clinical significance, on the other hand, does relate to the importance of a particular finding. A difference in outcomes between treated and control patients “becomes clinically significant when it leads to changes in clinical behavior” (38). In the case of sat versus conventional therapy, either a difference in favour of sat or no difference between them is relevant since, in the latter instance, the implication is that by using intravenous to oral switchover money is saved, there is improvement in the quality of life for the patient, or both.

Among these six papers, the main flaws are in the statistical considerations. From the point of view of experimental design, the best study was that of Kalager et al (39). The control arm consisted of two drugs – both effective against most aerobic Gram-negative bacillary pathogens. The sample size was the largest, and the statistical analysis was the most rigorous. Only three of the six studies (40–42) examined patients with only one type of infection, while the other three (39,42,43) studied patients with a variety of infections, eg, lower respiratory tract, urinary tract, and skin and soft tissue infections.

In one trial (not included in any of the tables) both comparative and noncomparative study arms were used (45). The comparative arm randomized patients to either ofloxacin or a third-generation cephalosporin (ceftazidime or ceftriaxone) for treatment of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or skin and soft tissue infection. However, of the 22 patients randomized to receive ofloxacin, only eight were given sequential intravenous to oral treatment. It is not clear from the paper whether a direct comparison was made between this small group of eight patients and those receiving intravenous therapy alone with a third-generation cephalosporin. The authors do, however, state that “none of the eight subjects who were randomized to ofloxacin and who received initial parenteral therapy deteriorated when switched to oral ofloxacin therapy.” In the noncomparative study arm, patients were treated with oral ofloxacin only.

IMPLEMENTATION OF SAT

In hospitals where sat programs are particularly successful, they are usually developed jointly by the infectious disease and pharmacy departments working in conjunction with the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. To facilitate the introduction of sat into a particular hospital, the appropriate infrastructure must first be created. To do this, the collaborative efforts of members of the pharmacy, microbiology, infectious disease, nursing and administration departments are required. The multidisciplinary perspective provided by these groups allows the successful implementation of recommendations made by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee.

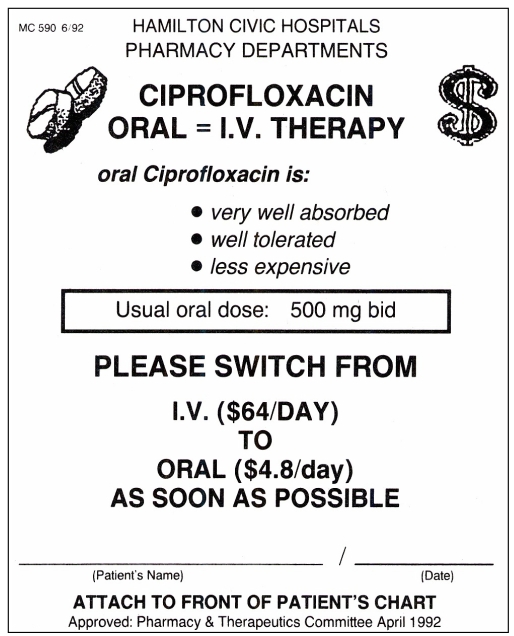

Integral to this program is the use of ‘sequential therapy reminders’. These educational tools, developed at the Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre, are highly visible printed forms with the necessary information on them (46). At the Henderson General Division of the Hamilton Civic Hospitals, for example, when a patient is started on a drug intravenously for which an oral preparation is also available, the pharmacist sends the sequential therapy reminder, printed on bright yellow paper, to the ward together with the intravenous drug. The ward nurse then attaches this yellow sheet to the front of the patient’s chart, where it remains until the intravenous drug is either discontinued or changed to an oral form. An example of such a form is provided in Figure 1. Information relevant to sat is printed on the form, thereby providing an educational service as well as a reminder to the physician that oral therapy should be considered.

Figure 1).

An example of sequential therapy reminders (reference 46)

Some of the challenges in the implementation of sat are resistance to change on the part of medical colleagues; a perceived increase in workload by those involved in managing the sat program; and physician reluctance because of medical and/or legal concerns. Experience with sat programs has shown that they are, in fact, relatively easy to implement and are readily accepted by physicians and other health care personnel provided that the appropriate leg-work is done and the necessary infrastructure is first created. To help implement sat, it is imperative that colleagues be educated concerning antimicrobial costs, support of chiefs of services as well as colleagues be enlisted, and continuous surveillance and feedback to colleagues regarding the success of the program be assured.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the 1970s, medical literature has documented the clinical efficacy of converting patients from intravenous antibiotic therapy to oral antibiotic therapy as early as three days after initiation of intravenous therapy in stable patients. Yet, such patients traditionally have not been given oral therapy until hospital discharge, ie, usually after at least seven days of intravenous treatment. The use of drugs that have virtually equivalent bioavailability in intravenous and oral forms, such as metronidazole, clindamycin, fluconazole and ciprofloxacin, can help alleviate physician concerns about suboptimal drug concentrations when converting to oral therapy, and can perhaps increase the acceptance of sat. A critical review of the medical literature supports the role of sat. What is also clear, however, is that further studies are necessary to determine the ideal time for intravenous to oral conversion and factors that may limit or impede the use of oral therapy.

We conclude that sat is not only an important tool for realizing substantial cost savings in the treatment of patients with serious infections, but can greatly add to patient comfort and productivity. Hospitals must play a proactive educational role in implementing sat programs if this important therapeutic strategy is to become the future standard of care.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by Bayer Inc Healthcare Division.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, Canada . Fifth Annual Report, for the year ended December 31, 1992. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada; 1993. pp. 16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.IMS Data: Drugstore and Hospital Purchases. 1992. Plymouth Meeting: IMS America.

- 3.Health Services Directorate, Health Services and Promotion Branch; and Bureau of Communicable Disease Epidemiology, Health Protection Branch, Health and Welfare Canada Guidelines for antimicrobial utilization in health care facilities. Can J Infect Dis. 1990;1:64–70. doi: 10.1155/1990/216712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigin RD, Pickering LK, Anderson D, Keeney RE, Shackleford PG. Clindamycin treatment of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. Pediatrics. 1975;55:213–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker SH. Staphylococcal osteomyelitis in children. Success with cephalordine-cephalexin therapy. Clin Pediatr. 1973;12:98–100. doi: 10.1177/000992287301200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tetzlaff TR, McCracken GH, Nelson JD. Oral antibiotic therapy for skeletal infections of children. II. Therapy of osteomyelitis and suppurative arthritis. J Pediatr. 1978;92:485–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryson YJ, Connor JD, LeClerc M, Giammona ST. High-dose dicloxacillin treatment of acute staphylococcal osteomyelitis in children. J Pediatr. 1979;94:673–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prober CG, Yeager AS. Use of the serum bactericidal titer to assess the adequacy of oral antibiotic therapy in the treatment of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. J Pediatr. 1979;95:131–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintiliani R, Nightingale CH, Crowe HM, Cooper BW, Bartlett RC, Gousse G. Strategic antibiotic decision-making at the formulary level. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 9):S770–S777. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_9.s770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frighetto L, Nickoloff D, Martinusen SM, Mamdani FS, Jewesson PJ. Intravenous-to-oral stepdown program: four years of experience in a large teaching hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:1447–51. doi: 10.1177/106002809202601119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jewesson P. Cost-effectiveness and value of an IV switch. PharmacoEconomics. 1994;5(Suppl 2):20–6. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199400052-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly JS, Worthington MG, Razvi SA, Robillard R. Brief report: intravenous and sequential intravenous and oral ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):232S–4S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson JD, Bucholz RW, Kusmiesz H, Shelton S. Benefits and risks of sequential parenteral-oral cephalosporin therapy for suppurative bone and joint infections. J Pediatr Orthop. 1982;2:255–62. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briceland LL, Nightingale CH, Quintiliani R, Cooper BW, Smith KS. Antibiotic streamlining from combination therapy to monotherapy utilizing an interdisciplinary approach. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2019–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rush DR. Antimicrobial formulary management: meeting the challenge in the community hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11(1 pt 2):19S–26S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plumridge RJ. Cost comparison of intravenous antibiotic administration. Med J Aust. 1990;153:516–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quintiliani R, Cooper BW, Briceland LL, Nightingale CH. Economic impact of streamlining antibiotic administration. Am J Med. 1987;82(Suppl 4A):391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright DB. Antimicrobial formulary management: a case study in a teaching hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11(1 pt 2):27S–31S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chrysanthopoulos CJ, Skoutelis AT, Bassaris HP. Shortened hospital stay with sequential intravenous oral ciprofloxacin. Drugs. 1993;45(Suppl 3):464. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grasela TH, Jr, Paladino JA, Schentag JJ, et al. Clinical and economic impact of oral ciprofloxacin as follow-up to parenteral antibiotics. DICP. Ann Pharmacother. 1991;25:857–62. doi: 10.1177/106002809102500724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paladino JA, Sperry HE, Backes JM, et al. Clinical and economic evaluation of oral ciprofloxacin after an abbreviated course of intravenous antibiotics. Am J Med. 1991;91:462–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90181-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA. 1985;261:3273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antibiotic drug interactions. Drug Interact Updates. 1993;13:199–284. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Intravenous ciprofloxacin. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1991;33:75–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson JD. A critical review of the role of oral antibiotics in the management of hematogenous osteomyelitis. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 1983;4:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCracken GH., Jr New era for orally administered antibiotics: use of sequential parenteral-oral antibiotic therapy for serious infectious diseases of infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:951–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Earl P, Sisson PR, Ingham HR. Twelve-hourly dosage schedule for oral and intravenous metronidazole. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;23:619–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/23.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yogev R, Kolling WM, Williams T. Pharmacokinetic comparison of intravenous and oral chloramphenicol in patients with Haemophilus influenzae meningitis. Pediatrics. 1981;67:656–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant SM, Clissold SP. Fluconazole. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs. 1990;39:877–916. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199039060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nightingale CH. Pharmacokinetic considerations in quinolone therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:34S–8S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffken G, Lode H, Prinzing C, Borner K, Koeppe P. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin after oral and parenteral administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:375–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monk JP, Campoli-Richards DM. Ofloxacin: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1987;33:346–91. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198733040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCracken GH., Jr Comparative evaluation of the aminopenicillins for oral use. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1983;2:317–20. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergan T, Thorsteinsson SB, Solberg R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin: intravenous and increasing oral doses. Am J Med. 1987;82(Suppl 4A):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise R, Griggs D, Andrews JM. Pharmacokinetics of the quinolones in volunteers: a proposed dosing schedule. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(Suppl 1):S83–S89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cipro Product Monograph. Etobicoke: Bayer Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gentry LO. Prescribing considerations in fluoroquinolone therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13(2 pt 2):39S–44S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University Health Sciences Centre How to read clinical journals: V: To distinguish useful from useless or even harmful therapy. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;124:1156–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalager T, Andersen BM, Bergan T, et al. Ciprofloxacin versus a tobramycin/cefuroxime combination in the treatment of serious systemic infections: a prospective, randomized and controlled study of efficacy and safety. Scand J Infect Dis. 1992;24:637–46. doi: 10.3109/00365549209054651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dominguez J, Palma F, Vega ME, et al. Brief report: prospective, controlled, randomized non-blind comparison of intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin with intravenous ceftazidime in the treatment of skin or soft-tissue infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):136S–7S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox CE. Brief report: sequential intravenous and oral ciprofloxacin versus intravenous ceftazidime in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):157S–9S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gangji D, Jacobs F, de Jonckheer J, et al. Brief report: randomized study of intravenous versus sequential intravenous/oral regimen of ciprofloxacin in the treatment of Gram-negative septicemia. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):206S–8S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaut PL, Carron WC, Ching WTW, Meyer RD. Intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin therapy versus intravenous ceftazidime therapy for selected bacterial infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):169S–75S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fass RJ, Plouffe JF, Russell JA. Intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin versus ceftazidime in the treatment of serious infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):164S–8S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicolle LE, Guay D, Degelau J, et al. Efficacy of ofloxacin for the treatment of penumonia, skin and skin structure infection, and urinary tract infection in an elderly population. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1993;2:414–22. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bunz DM, Frighetto L, Gupta S, Jewesson PJ. Simple ways to promote cost containment. DICP. Ann Pharmacother. 1990;24:546. doi: 10.1177/106002809002400519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirata-Dulas CAI, Stein DJ, Guay DRP, Gruninger RP, Peterson PK. A randomized study of ciprofloxacin versus ceftriaxone in the treatment of nursing home-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:979–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan FA, Basir R. Sequential intravenous-oral administration of ciprofloxacin vs ceftazidime in serious bacterial respiratory tract infections. Chest. 1989;96:528–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menon L, Ernst JA, Sy ER, Flores D, Pacia A, Lorian V. Brief report: sequential intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin compared with intravenous ceftazidime in the treatment of serious lower respiratory tract infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):119S–20S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peacock JE, Pegram PS, Weber SF, Leone PA. Prospective, randomized comparison of sequential intravenous followed by oral ciprofloxacin with intravenous ceftazidime in the treatment of serious infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):185S–90S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feist H. Sequential therapy with I.V. and oral ofloxacin in lower respiratory tract infections: A comparative study. Infection. 1991;19(Suppl 7):380–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01715832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khajotia R, Drlicek M, Vetter N. A comparative study of ofloxacin and amoxycillin/clavulanate in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26(Suppl D):83–91. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.suppl_d.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson JR, Lyons MF, Pearce W, et al. Therapy for women hospitalized with acute pyelonephritis: A randomized trial of ampicillin versus trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole for 14 days. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:325–30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chrysanthopoulos CJ, Starakis JC, Skoutelis AT, Bassaris HP. Brief report: sequential intravenous/oral therapy with ciprofloxacin in severe infection. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):225S–7S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouza E, Diaz-Lopez MD, Bernaldo de Quiros JCL, Rodriguez-Creixems M. Ciprofloxacin in patients with bacteremic infections. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):228S–37S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chayakul P, Krisanapan S, Kalnauwakul S. Sequential intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe multiresistant Gram-negative infections. J Med Assoc Thai. 1993;76:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dworkin RJ, Sande MA, Lee BL, Chambers HF. Treatment of right-sided Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in intravenous drug users with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin. Lancet. 1989;ii:1071–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neu HC, Davidson S, Briones F. Intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin therapy of infections caused by multiresistant bacteria. Am J Med. 1989;87(Suppl 5A):209S–12S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scully BE, Neu HC. Treatment of serious infections with intravenous ciprofloxacin. Am J Med. 1987;82(Suppl 4A):369–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giamarellou H, Galanakis N. Use of intravenous ciprofloxacin in difficult-to-treat infections. Am J Med. 1987;82(Suppl 4A):346–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gentry LO, Rodriguez-Gomez G, Kohler RB, Khan FA, Rytel MW. Parenteral followed by oral floxacin for nosocomial penumonia and community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:31–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Auten GM, Preheim LC, Sookpranee M, Bittner MJ, Sookpranee T, Vibhagool A. High-pressure liquid chromatography and microbiological assay of serum ofloxacin levels in adults receiving intravenous and oral therapy for skin infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2558–61. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.12.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soper DE, Brockwell NJ, Dalton HP. Microbial etiology of urban emergency department acute salpingitis: treatment with ofloxacin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:653–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heppt W, Lutz H. Clinical experiences with ofloxacin sequential therapy in chronic ear infections. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;250:S19–S21. doi: 10.1007/BF02540112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lentino JR, Augustinsky JB, Weber TM, Pachucki CT. Therapy of serious skin and soft tissue infections with ofloxacin administered by intravenous and oral route. Chemotherapy. 1991;37:70–6. doi: 10.1159/000238836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gelfand MS, Simmons BP, Craft RB, Grogan J, Amarshi N. A sequential study of intravenous and oral fleroxacin in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infection. Am J Med. 1993;94(Suppl 3A):126S–30S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aronoff SC, Scoles PV, Makley JT, Jacobs MR, Blumer JL, Kalamchi A. Efficacy and safety of sequential treatment with parenteral sulbactam/ampicillin and oral sultamicillin for skeletal infections in children. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(Suppl 5):S639–43. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_5.s639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schaad UB, Pfenninger J, Wedgewood-Krucko J. Sequential intravenous-oral amoxycillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) therapy in paediatric hospital practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;19:385–91. doi: 10.1093/jac/19.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buchi W, Casey PA. Experience with parenteral and sequential parenteral-oral amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) in hospitalized patients. Infection. 1988;16:306–12. doi: 10.1007/BF01645083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]