Summary

The purpose of this study was to improve clinical assessment of carotid-blowout syndrome (CBS) in patients with head-and-neck cancers and with covered stents by evaluating immediate and delayed complications of reconstructive management. Eleven such patients were treated with self-expandable covered stents. We evaluated immediate and delayed complications by assessing clinical and imaging findings. Technical success and immediate hemostasis were achieved in all patients. Immediate complications were noted in four patients (36.4%), including thromboembolism in three patients and, in one patient, dissection of the carotid artery and type III endoleak by the overlapped self-expandable stent causing rebleeding. Delayed complications were noted in eight patients (72.7%), including six episodes of rebleeding in five patients, distal marginal stenosis in five patients, and delayed carotid thrombosis in three patients (one with brain abscess formation). We suggest close follow-up of the patients and aggressive re-intervention of their complications to improve outcomes.

Key words: complications, carotid blowout syndrome, head and neck cancer, covered stents

Introduction

Carotid blowout syndrome (CBS) refers to the clinical signs and symptoms related to rupture of the carotid artery and its branches1-4. It is the most feared complication associated with therapy for head-and-neck cancers. Published mortality rates of 9-100% and major neurological complication rates of 16-100% have been reported3. Traditional management has consisted of surgical ligation of the involved vessels and is often technically difficult because of previous surgery or irradiation of the head and neck region. Deconstructive endovascular therapy such as permanent balloon occlusion has shown considerable promise in the management of CBS1-5. However, 15-20% of patients with carotid-blowout syndrome who are treated with such deconstructive endovascular management have immediate or delayed cerebral ischemia1,6. For patients at risk of carotid occlusion, reconstructive management with covered stents was reported to be a viable alternative. However, recent studies on reconstructive endovascular treatment in patients of head-and-neck cancers with CBS have described unfavorable long-term outcomes due to various complications 5,7. The purpose of this study was to improve clinical assessment of CBS in patients with head and neck cancer by evaluating the range of immediate and delayed complications that occur after endovascular reconstruction using covered stents.

Materials and Method

Patient Population

Over four years, eleven patients with head and neck cancers with CBS were enrolled in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of reconstructive management of 11 CBS patients.

| CBS & Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No./ Age (y)/Sex |

Cancer and Treatment History | Group | Location | Initial Management: covered stent (mm)* |

| 1/35/M | Malignant mixed tumor, submandibular gland; wide excision, RT, CT |

A | CBF | 8 x 50 |

| 2/42/M | Tonsillar CA, wide excision, RT | A | CCA | 8 x 30 |

| 3/49/M | NPC, RT; 2nd primary hypopharyngeal CA, CCRT 1 yr ago |

I | ICA | 8 x 50‡ |

| 4/52/M | Hypopharyngeal CA, RT | I | CBF | 8 x 50‡ |

| 5/54/M | Hypopharyngeal CA & esophageal CA, laryngectomy & esophagectomy, CCRT |

I | CCA | 9 x 70 |

| 6/52/M | Laryngeal CA, laryngectomy, RT | A | ICA | 7 x 30 |

| 7/65/M | Laryngeal CA, RT | A | CCA | 8 x 50 |

| 8/44/M | Hypopharyngeal CA, total pharyngolaryngectomy, RT |

T | CCA | 9 x 70 |

| 9/53/M | Esophageal CA, esophagectomy; 2nd primary hypopharyngeal CA, CCRT |

A | CBF | 8 x 50‡ |

| 10/44/M | LT tongue CA, radical neck dissection & RT; 2nd primary hypopharyngeal CA, RT 1 y ago |

T | CBF, CCA | 8 x 50 & 9 x 70‡ |

| 11/51/M | Hypopharyngeal CA, pharyngectomy, RT | T | CBF, CCA | 8 x 50 & 9 x 70‡ |

|

Group of clinical severity: A = acute CBS, I = impending CBS, T = threatened CBS; CA = cancer; CCRT = concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CT = chemotherapy; RT = radiotherapy; CBF = carotid bifurcation; CCA = common carotid artery; ICA = internal carotid artery Initial technical success and immediate hemostasis were achieved in all patients. *Wallgraft; Boston Scientific Corporation. | ||||

All had received radiation therapy or chemoradiotherapy. CBS was classified into 3 types: threatened, impending, and acute1,3. Locations of pathologic vascular lesions, such as pseudoaneurysms, were recorded as the cervical ICA, carotid bifurcation (CBF), or common carotid artery (CCA). Indications for patients treated with self-expandable stent-grafts were: 1) the circle of Willis was incomplete on angiogram (n=2), 2) they were in unstable clinical condition (eg, acute or impending carotid-blowout syndrome) that precluded balloon occlusion testing (n=6), or 3) they could not tolerate a balloon occlusion test (n=3)6,7.

Medications

Patients with threatened CBS were premedicated with a dual antiplatelet regimen consisting of orally administered aspirin (324 mg) and clopidogrel (300 mg) 1 day before treatment. Patients with acute or impending CBS were prophylactically given intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor (Aggrastat; Merck & Co, Inc, West Point, PA, USA) during the interventional procedure7. Approximately 50-70 U/ kg of heparin was also given except for the 3 patients (cases 1,2, & 9) with very profuse bleeding. After deployment of the self-expandable stent-graft, a dual antiplatelet regimen was begun. After one month, this regimen was changed to aspirin (100 mg) for life-long use. Because the patient in case 4 suffered from brain abscesses after the stent-graft deployment, we gave four-week prophylactic antibiotic therapy to cases 7-11.

Interventional procedures

During the procedure, we used a transfemoral arterial approach to obtain a complete neuroangiogram of the supra-aortic arteries and their branches. If we decided to deploy a self-expandable stent-graft, we placed a 10-11F sheath through the right femoral artery. A 300 cm exchange guide wire (Amplatz; Cook, Bloomington, IN) was placed into the cervical ICA. A self-expandable stent-graft (Wallgraft; Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA) was selected and then advanced along this exchange guide wire to the diseased carotid artery. The interventional management was finished when clinical hemostasis and adequate coverage of the pathological lesion by stentgraft were gained.

Patient Evaluation and Follow-Up

We evaluated outcomes by clinical and image studies, including technical success, immediate and delayed complications, and patency of the stent-grafts. The complications presented during the therapeutic procedures were defined as "immediate" and those presented after the procedures were defined as "delayed". Patients underwent follow-up contrast-enhanced CT, CT angiography, sonography, or conventional angiography within the first month and then every 2-4 months thereafter so that patency of the stent-grafts could be assessed. We recorded the immediate and delayed complications and their causes. Follow-up lasted from 0.1 to 37 months.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of all 11 patients. In all patients, CBS was successfully managed by an initial therapeutic procedure that deployed one or two self-expandable stent-grafts, with immediate hemostasis.

* Immediate Complications

Four causes of immediate complications were noted in four patients (36.4%), including associated carotid stenosis with acute carotid occlusion in one patient (case 1), inadequate antithrombotic medications with acute thromboembolism in two patients (cases 3,4), and iatrogenic dissection and type 3 endoleak after overlapping with a self-expandable stent (Wallstent, Boston Scientific Co) in one patient (case 9).

* Delayed Complications

Delayed complications of our patients are summarized in Table 2. Delayed complications were noted in eight patients (72.7%).

Table 2.

Delayed complications in 11 CBS patients treated with self-expandable stent-grafts.

| Complication | Case No. | Time* ( mos) | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rebleeding | 2 | 0.1 | Inadequate coverage of the pathological lesion by poor cooperation of the patient |

| 3,6 | 0.5,2 | Disease progression extending beyond the margin of covered stent |

|

| 1,6 | 0.6,3 | Disease progression involving the branches of ECA |

|

| Distal marginal stenosis | 3, 6, 9-11 | 3,3.7, 4,4,4 | Strong radial and straightening force of the covered stents |

| Occlusion of stent-graft | 3, 6 | 6,6 | Distal marginal stenosis and/or contiguous infection |

| Septic thrombosis with brain abscess formation |

5 | 4 | Contaminated wound with persistent infection |

|

Time* = time interval between initial management and presence of delayed complications ECA = external carotid artery | |||

Discussion

The covered stent (Wallgraft; Boston Scientific Corporation) that we used is an expandable metal mesh covered by polyethylene terephthalate. This self-expandable stent-graft requires favorable anatomic conditions and appropriate pathophysiologic conditions. Associated carotid stenosis can hinder full expansion of the covered stent, which may impede blood flow and cause acute thrombus formation. Covered stents in general are more thrombogenic than bare stents, and therefore require more aggressive and prolonged antiplatelet therapy during and after management7,8. The use of a stent-graft in a field with contaminated necrosis may result in persistent infection as infective organisms colonize the foreign material.

The causes of poor long-term stent-graft patency were as follows.

1) Appropriate antithrombotic medications are usually not effective in cases of acute or advanced clinical status. We suggest early diagnosis and early management for patients in stable condition to provide adequate antithrombotic regimens.

2) When stent-grafts are deployed in a contaminated field in patients with head-and-neck cancers, it may result in persistent infection and ultimately cause septic thrombosis of the carotid artery7. We suggest prophylactic antibiotics for the intervention.

3) Distal marginal stenosis is a common cause of recurrent vascular narrowing or occlusion after stent-graft deployment9. It may be caused by vascular remodeling to the high radial force of the self-expandable stent-grafts 10,11.

As it shows rapid temporal change, close follow-up and early management are needed to improve outcomes.

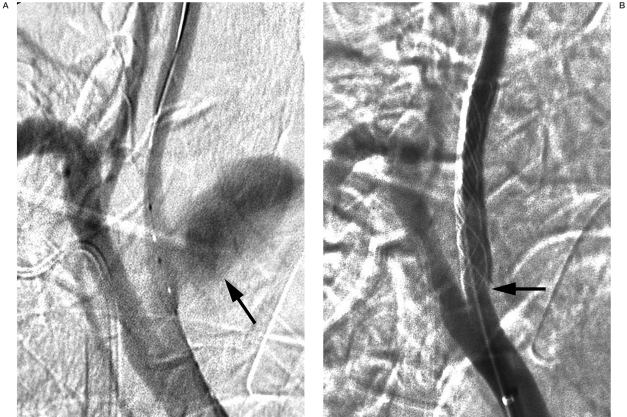

Figure 1.

Patient 2. A) Innominate artery angiogram shows a pseudoaneurysm in the right proximal common carotid artery (CCA;arrow). B) An 8 ? 30 mm stent (Wallgraft;Boston Scientific Corporation) was deployed in the right proximal CCA. Note the proximal end of the deployed stent merely covered the margin of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow) because the patient was in an uncooperative mood. He suffered from massive rebleeding and died on the second post-operative day.

The pathologic field of the head and neck cancer can show temporal and dynamic changes as a result of complex factors, such as tumor recurrence, infection, and radiation-induced necrosis. This ongoing pathologic process may progress over the area initially treated and cause rebleeding. A long, self-expandable stent-graft can fully cover the pathologic field and reduce the risk of rebleeding from disease progression. Associated embolization of the branches of the external carotid artery close to the pathological field can also prevent rebleeding from disease progression7.

Conclusions

Deployment Of Covered Stents In Patients With Head-And-Neck Cancer And Cbs Is Associated With Various Initial And Delayed Complications. The Immediate Complications are acute thromboembolism and carotid dissection. The delayed complications include rebleeding, distal marginal stenosis, occlusion of the covered stents and septic thrombosis with brain abscess formation. Close follow-up the patients after the procedures and aggressive management of these complications are needed to improve outcomes.

Note Added in Proof

* Supported partly by Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V97B1-007)

References

- 1.Chaloupka JC, Putman CM, et al. Endovascular therapy for the carotid blowout syndrome in head and neck surgical patients: Diagnosis and managerial considerations. Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:843–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macdonald S, Gan J, et al. Endovascular treatment of acute carotid blowout syndrome. JVIR. 2000;11:1184–1188. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Citardi MJ, Chaloupak JC, et al. Management of carotid artery rupture by monitored endovascular therapeutic occlusion (1988-1994) Laryngoscope. 1995;105:1086–1092. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199510000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaloupka JC, Roth TC, et al. Recurrent carotid blowout syndrome: Diagnosis and therapeutic challenges in a newly recongnized subgroup of patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1069–1077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren FM, Cohen JI, et al. Management of carotid "blowout" with endovascular stent grafts. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:428–433. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesley WS, Chaloupka JC, et al. Preliminary experience with endovascular reconstruction for the management of carotid blowout syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:975–981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang FC, Lirng JF, et al. Carotid blowout syndrome in patients with head-and-neck cancers: reconstructive management by self-expandable stent-grafts. Am J Nueroradiol. 2007;28:181–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sovik E, Klow NE, et al. Elective placement of covered stents in native coronary arteries. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:294–301. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0455.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gercken U, Lansky AJ, et al. Results of the Jostent coronary stent graft implantation in various clinical settings: procedural and follow-up results. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2002;56:353–360. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka N, Martin J-B, et al. Conformity of carotid stents with vascular anatomy: evaluation in carotid models. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:604–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkefeld J, Turowski B, et al. Recanalization results after carotid stent placement. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:113–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]