Abstract

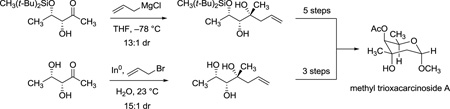

Two routes to the 2,6-dideoxysugar methyl trioxacarcinoside A are described. Each was enabled by an apparent α-chelation-controlled addition of an allylmetal reagent to a ketone substrate containing a free α-hydroxyl group and a β-hydroxyl substituent, either free or protected as the corresponding di-tert-butylmethyl silyl ether. Both routes provide practical access to gram-quantities of trioxacarcinose A in a form suitable for glycosidic coupling reactions.

Trioxacarcinose A (1) is a rare deoxysugar found within many trioxacarcins, densely oxygenated bacterial metabolites with antiproliferative effects in cultured human cancer cells.1 Trioxacarcin A (2), the most potent member of the trioxacarcin natural product class (Figure 1), contains both trioxacarcinose A and B residues, each with an α-linkage. The desacetyl form of trioxacarcinose A, axenose (3), is also naturally occurring and was earlier known, appearing within the natural products axenomycin, polyketomycin, and dutomycin.2 Two prior synthetic routes to axenose have been published.3,4 The first proceeded in 13 steps (1.6% yield) from l-fucose as starting material3a and the second proceeded in 12 steps (~4% yield) from 2-deoxy-d-ribose as starting material.3b Here we describe two different synthetic routes to the axenose–trioxacarcinose A carbohydrate class. Both routes rely upon diastereoselective addition reactions of allylmetal reagents to α,β-dioxygenated ketones and employ the crystalline substance 4-phenylbenzyl (2R,3S)-dihydroxybutyrate as starting material.5 The routes we present have allowed us to prepare gram-quantities of optically pure trioxacarcinose A in a form suitable for glycosidic coupling reactions.

Figure 1.

Structures of α-trioxacarcinose A (1), trioxacarcin A (2), and α-axenose (3).

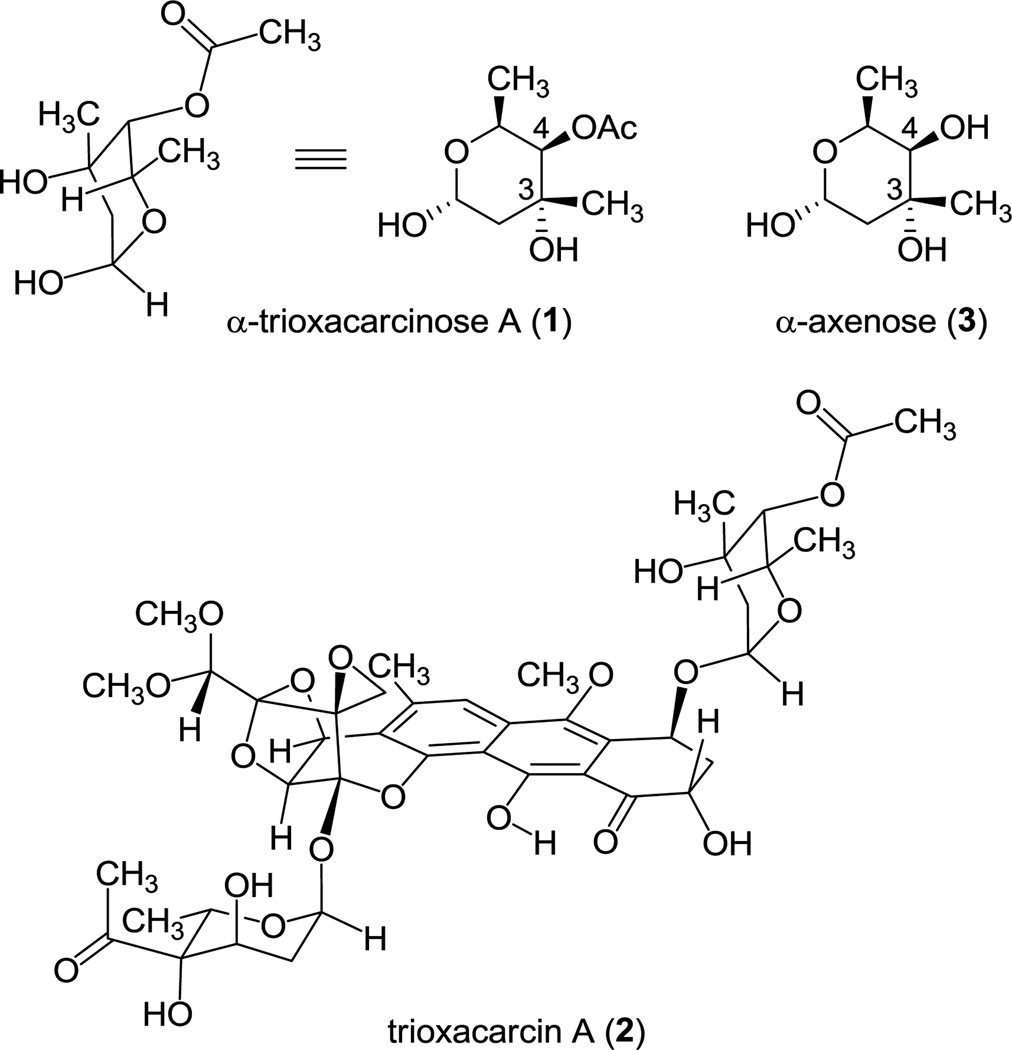

Considering the open-chain or aldehydic form of trioxacarcinose A (Scheme 1), we focused on retrosynthetic operations that would disconnect carbons 2 and 3. This led us to envision, in the synthetic direction, stereocontrolled addition of an allyl Grignard reagent to (3R,4S)-dihydroxy-2-pentanone with the expectation that our selection of diol protective group(s) might influence the addition; however, the literature did not offer clear guidance on what diol-protecting scheme might ensure the desired stereochemical outcome. While α-chelation-controlled6 additions of Grignard reagents to 2-tetrahydrofuranyl and α-benzyloxy ketones have been featured in landmark syntheses of stereochemically complex natural products,7 additions of Grignard reagents to ketones with acyclic side-chains bearing both α- and β-oxygenated substituents are of less certain stereochemical outcome.8

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis of Trioxacarcinose A (1)

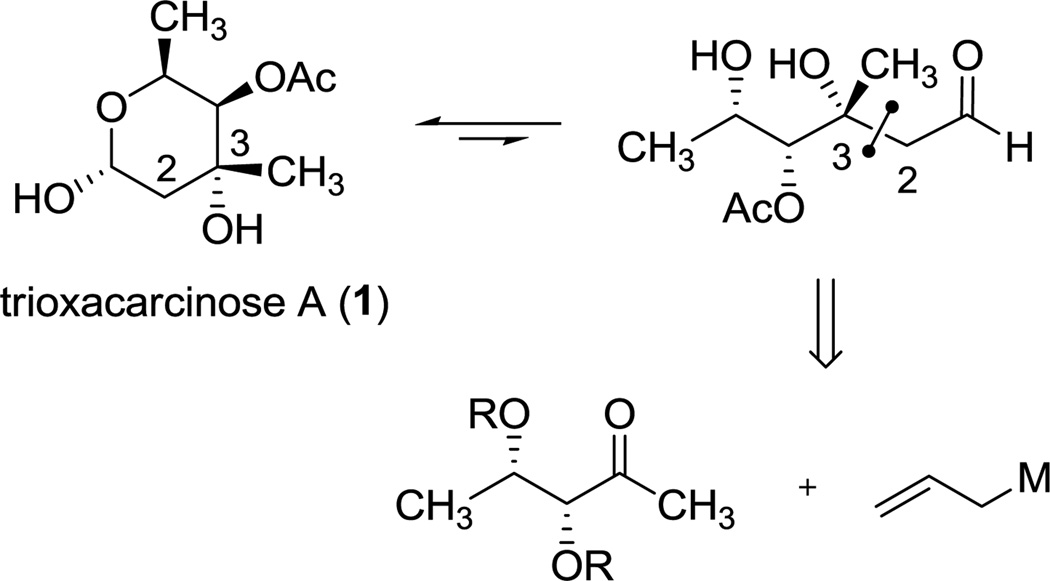

We briefly explored additions of Grignard reagents to acetonide-protected syn-2,3-dihydroxyketones 5 (methyl ketone) and 6 (allyl ketone)9 as summarized in Scheme 2; however, in neither case was the stereochemical outcome favorable for the purpose of synthesizing 1. Thus, addition of allylmagnesium chloride to methyl ketone 5 afforded predominantly the stereoisomer 7, which is not congruent with trioxacarcinose A at position C3, established by conversion of the adduct 7 to methyl 3-epi-axenoside (9) in a 3-step sequence (Scheme 2).4,10 The observed stereochemical course is consistent with either “polar Felkin–Anh”11 or β-chelation-controlled transition structures, but not an α-chelation-controlled addition. Interestingly, addition of methylmagnesium chloride to the allyl ketone 6 also afforded the tertiary alcohol 7 as the major product, which in this case corresponds to an α-chelation-controlled process. This is not the first instance where the stereochemical outcomes of addition reactions of allyl and methyl Grignard reagents to a common ketone substrate have been different.12

Scheme 2.

Additions to Acetonide-Protected syn-2,3-Dihydroxyketones

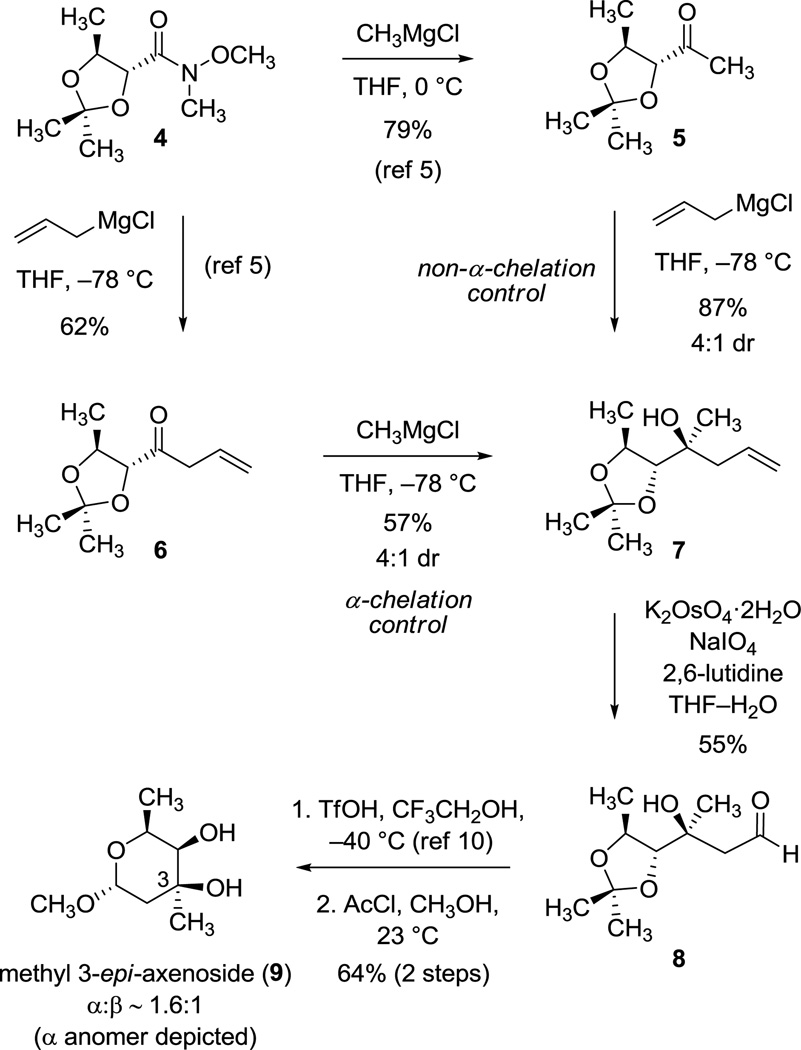

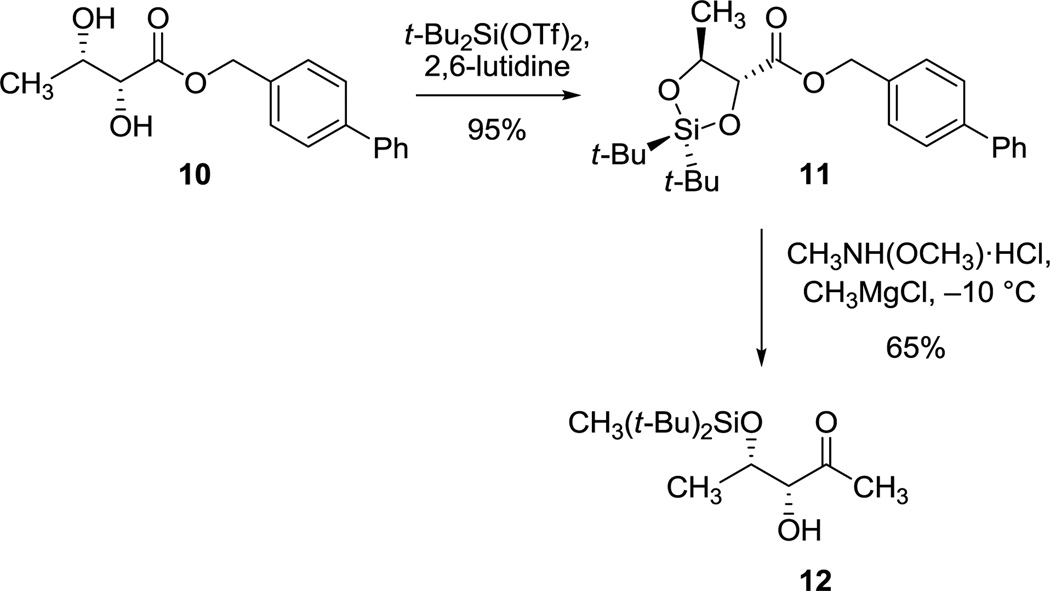

In light of the unfavorable stereochemical outcomes of addition reactions to the acetonide-protected ketone substrates 5 and 6, we were led to prepare the di-tert-butylsiloxane ester derivative 11 as substrate (95% yield, 12.7 g, Scheme 3),13 which was easily achieved using the readily available, optically pure diol ester 10 as starting material.5 Fortuitously, we observed that upon attempted transformation of the di-tert-butylsiloxane ester 11 into the corresponding methyl ketone using the Merck single-step process (via the Weinreb amide derivative)14,15 concomitant, regioselective cleavage of the cyclic siloxane group occurred, giving rise to the di-tert-butylmethyl silyl ether 12 (5.3 g, 65% yield). Although regioselective openings of di-tert-butylsiloxane derivatives with n-butyllithium have been described,16 we are unaware of corresponding transformations with Grignard reagents.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Methyl Ketone 12

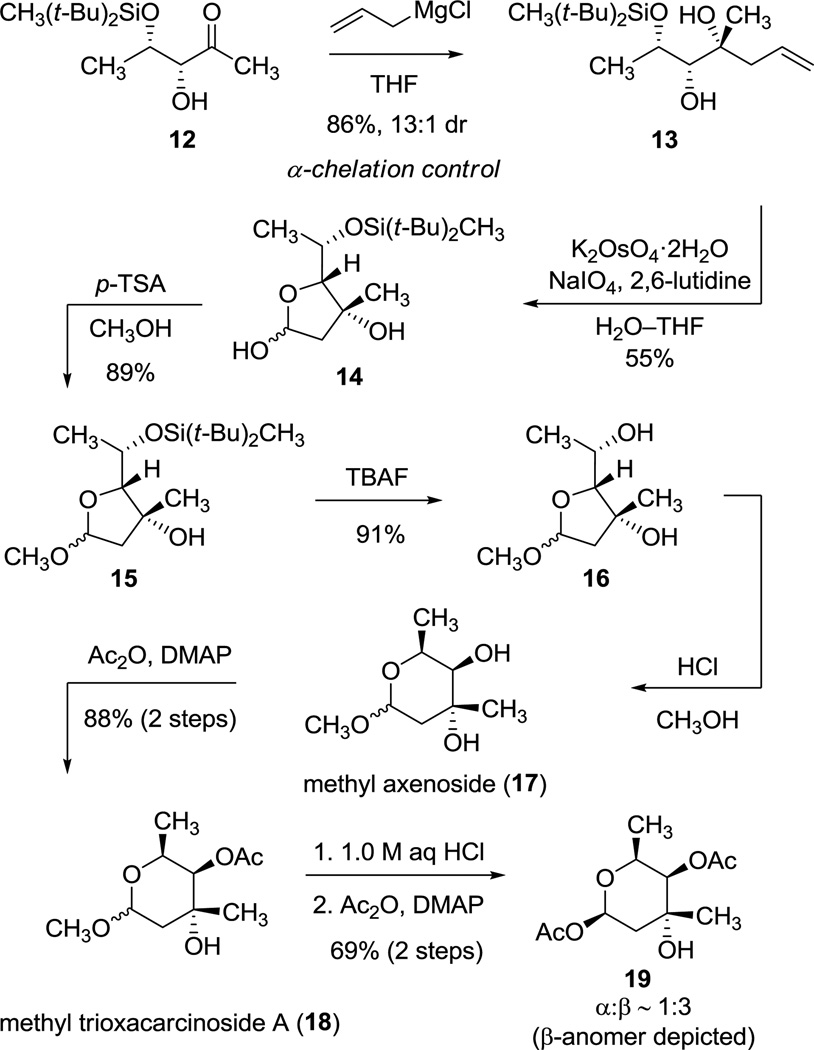

The selective transformation of the cyclic siloxane 11 to the monosilyl ether 12 proved to be quite useful, as it enabled our first synthetic route to trioxacarcinose A (Scheme 4). Addition of excess allylmagnesium chloride to α-hydroxyketone 12 in THF at −78 °C proceeded with 13:1 diastereoselectivity favoring the tertiary alcohol product 13, consistent with an α-chelation-controlled addition mechanism (3.59 g, 86% yield).17 The product (13) is stereochemically congruent with trioxacarcinose A (1), as established by its conversion to methyl axenoside (17), en route to 1, as detailed below.

Scheme 4.

Syntheses of Methyl Axenoside (17) and Methyl Trioxacarcinoside A (18)

Oxidative cleavage of the alkenyl side chain of 13 occurred in the presence of potassium osmate and sodium metaperiodate,18 providing the furanose derivative 14 as a mixture of anomers (1.97 g, 55% yield, α:β ≈ 1:5). Deprotection of the di-tert-butylmethylsilyl ether, a sterically hindered and robust protective group,19 was accomplished in two steps. The cyclic hemiacetal 14 was first transformed into the more stable methyl glycoside derivative 15 with p-toluenesulfonic acid in methanol (89% yield). The methyl glycoside then underwent smooth desilylation with TBAF at 23 °C to provide methyl furanosides 16 in 91% yield (890 mg). The latter product was isomerized to the more stable methyl pyranosides 17 (methyl α- and β-axenoside) with methanolic HCl at 23 °C, a known transformation.3b,20 Analytical data were in accord with those previously reported for methyl axenoside.3 Selective O-acetylation of 17 provided methyl trioxacarcinoside A 18 (970 mg, 88% over two steps). Analytical data were in agreement with values reported for the same substance derived from natural sources.21 Hydrolysis of 18 in 1.0 M aqueous hydrochloric acid provided trioxacarcinose A itself (1), which was acetylated at the anomeric position to give 1-O-acetyl glycoside 19 in 69% yield over two steps (α:β ≈ 1:3). 1-O-Acetyl glycosides are known to be effective glycosyl donors, do not require activation for coupling,22 and can also be transformed into a number of other different types of glycosyl donors.23

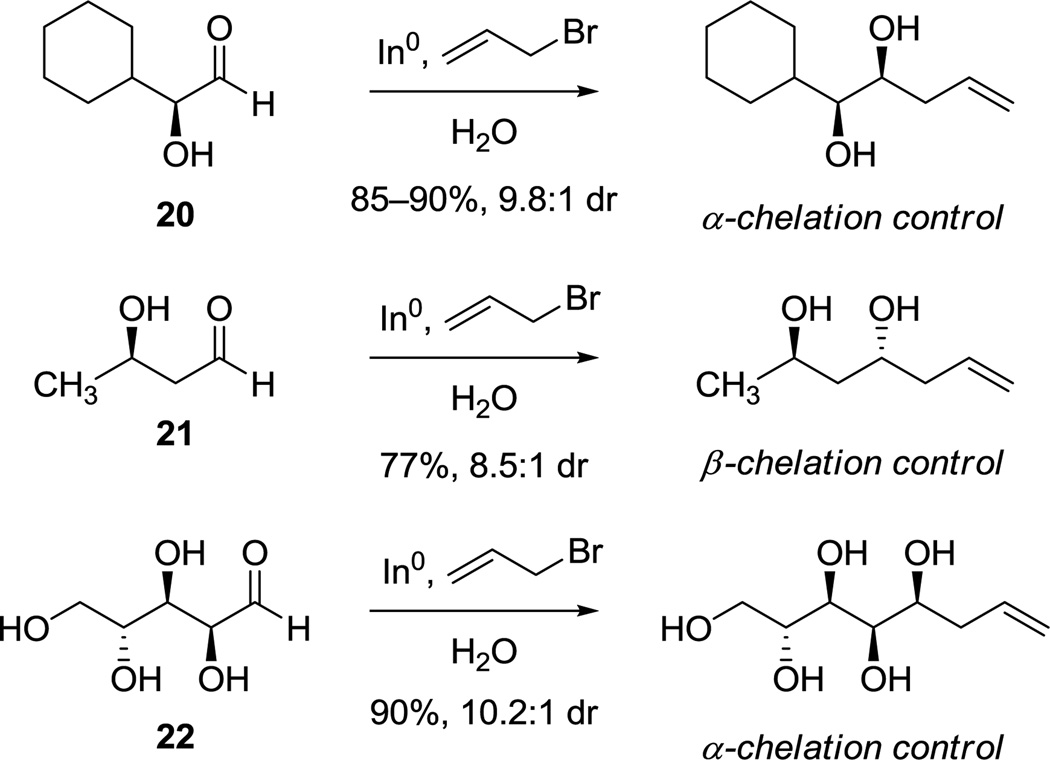

While the route outlined in Scheme 4 provided an effective and scalable means of synthesizing trioxacarcinose A and derivatives, an even shorter sequence was considered for investigation based upon a remarkable series of publications from Paquette and coworkers describing diastereoselective, indium-mediated allylation reactions of aldehyde and ketone substrates containing free hydroxyl groups, in water as solvent.24 For example (summarized in Scheme 5), Paquette and Mitzel showed that indium-mediated allylation of the α-hydroxyaldehyde 20 proceeded with high diastereoselectively to afford mainly the syn-product, consistent with an α-chelation-controlled addition mechanism, while allylation of the β-hydroxyaldehyde 21 provided primarily the anti-product, consistent with a β-chelation-controlled mechanism. They also reported the very interesting case of indium-mediated allylation of the polyol d-arabinose 22, where in principle the directing effects of the α- and β-hydroxyl groups were non-reinforcing (and the effects of γ- and δ-hydroxyl groups were unknown); the product of apparent α-chelation control was formed with high diastereoselectivity.24a The latter result was particularly germane, for it suggested that allylation of the specific dihydroxy ketone substrate (3R,4S)-dihydroxy-2-pentanone (23), with non-reinforcing α- and β-directing effects, might proceed in the desired sense (with α-chelation-control) to provide a practicable and extraordinarily short sequence to trioxacarcinose A.

Scheme 5.

Indium-Mediated Allylations of Hydroxyaldehydes as Described by Paquette and Mitzel.24a

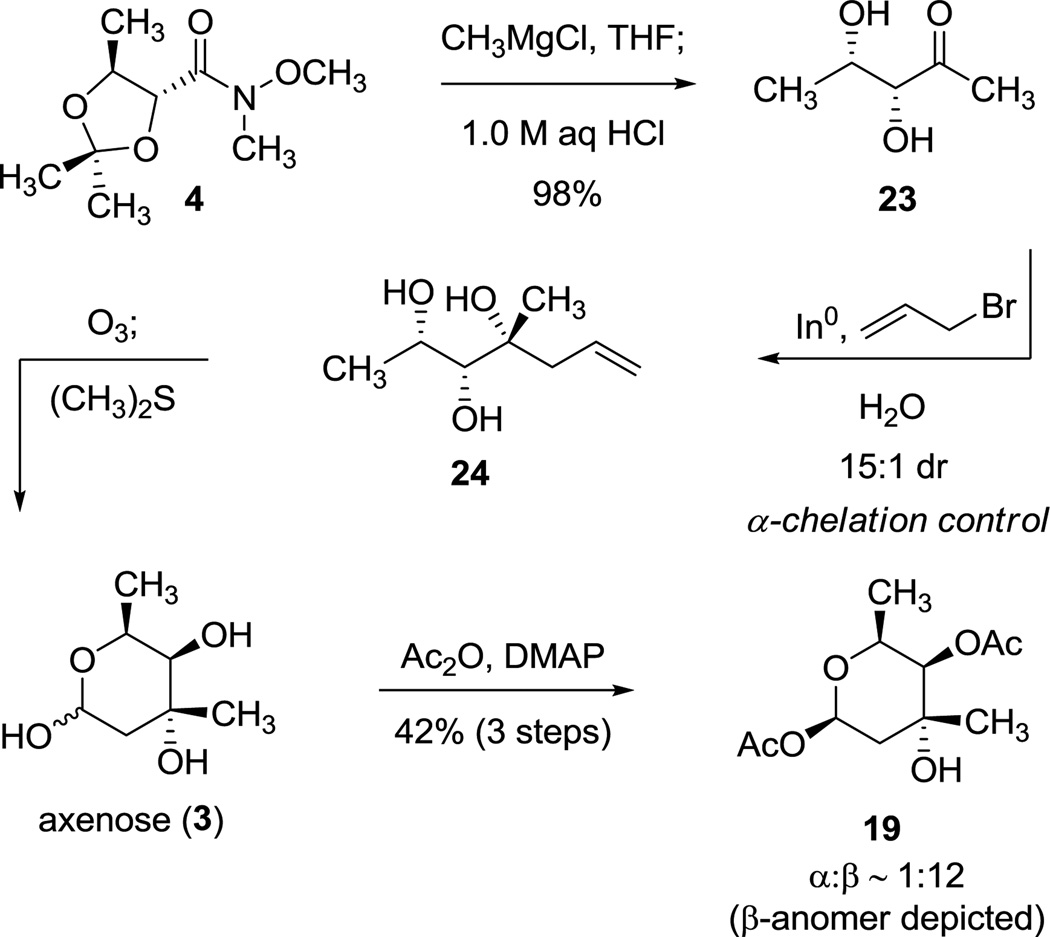

To investigate the feasibility of the shorter sequence we envisioned, we first transformed the Weinreb amide substrate 45,9 into ketone 23 (9.89 g, 98% yield), in a single operation (Scheme 6). Allylation of the latter product (23, 3.43 g) under conditions typical of those employed by Paquette and Mitzel,24b using indium powder (1.6 equiv) and allyl bromide (1.6 equiv) in water at 23 °C, did indeed proceed with predominant α-chelation control to provide the water-soluble triol 24 as a 15:1 mixture of diastereomers. Direct ozonolysis followed by reductive quenching with dimethylsulfide led to cleavage of the terminal alkene(s) to afford axenose (3), predominantly in its pyranose form. The crude product was then acetylated to afford 1-O-acetyl trioxacarcinose A (19, 42% yield over three steps from 23, 2.97 g, α:β ≈ 1:12) in >95% purity after chromatographic purification.25

Scheme 6.

Second-Generation Synthesis of 1-O-Acetyl Trioxacarcinose A (19)

Methanolysis of 1-O-acetyl trioxacarcinose A (19) synthesized by this second route (using acetyl chloride in methanol) produced methyl trioxacarcinoside A (18, 74% yield, see Supporting Information), which provided analytical data indistinguishable from those of 18 from our first route, described above. By virtue of its greater brevity and convenience, the second synthetic route provides an especially useful means of access to trioxacarcinose A in anomerically activated form.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (Grant CA047148) and the Department of Defense (National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship to D.J.S.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and characterization data (1H and 13C NMR, FT-IR, and HRMS) for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Tomita F, Tamaoki T, Morimoto M, Fujimoto K. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:1519–1524. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tamaoki T, Shirahata K, Iida T, Tomita F. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:1525–1530. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axenomycin: Arcamone F, Barbieri W, Franceschi G, Penco S, Vigevani A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2008–2009. doi: 10.1021/ja00787a048. Polyketomycin: Momosa I, Chen W, Kinoshita N, Iinuma H, Hamada M, Takeuchi T. J. Antibiot. 1998;51:21–25. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.21. Momosa I, Chen W, Nakamura H, Naganawa H, Iinuma H, Takeuchi T. J. Antibiot. 1998;51:26–32. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.26. Dutomycin: Xuan L-J, Xu S-H, Zhang H-L. J. Antibiot. 1992;45:1974–1976. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1974.

- 3.(a) Garegg PJ, Norberg T. Acta Chem. Scand. 1975;29:506–513. [Google Scholar]; (b) Giuliano RM, Villani FJ., Jr J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:202–211. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For a synthetic route to 3-epi-axenose, see: Roush W, Hagadorn S. Carbohydr. Res. 1985;136:187–193. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(85)85195-8.

- 5. Smaltz DJ, Myers AG. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:8554–8559. doi: 10.1021/jo2016746. The Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation reaction was central to this preparation of 4-phenylbenzyl (2R,3S)-dihydroxybutyrate; for a review, see: Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547.

- 6. Cram DJ, Kopecky KR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:2748–2755. Still WC, McDonald JH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;11:1031–1034. Reviews: Reetz MT. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:462–468. Mengel A, Reiser O. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:1191–1223. doi: 10.1021/cr980379w. Reetz MT. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;23:556–569.

- 7.(a) Nakata T, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:2745–2748. [Google Scholar]; (b) Collum DB, McDonald JH, III, Still WC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;102:2117–2120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Mulzer J, Angermann A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:2843–2846. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mead K, Macdonald TL. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:422–424. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Both substrates 5 and 6 were derived from 4-phenylbenzyl (2R,3S)-dihydroxybutyrate via the Weinreb amide acetonide 4, as summarized in Scheme 2.5

- 10.Cleavage of the acetonide protective group required the use of triflic acid in trifluoroethanol, conditions first described by the Hirama group in the context of their synthesis of N1999A2, see: Kobayashi S, Reddy RS, Sugiura Y, Sasaki D, Miyagawa N, Hirama M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2887–2888. doi: 10.1021/ja003982g.

- 11.Anh NT. Top. Curr. Chem. 1980;88:145–162. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carda M, González F, Rodríguez S, Marco JA. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:1799–1802. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Trost BM, Caldwell CG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4999–5002. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Hopkins PB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:4871–4874. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams J, Jobson RB, Yasuda N, Marchesini G, Dolling U-H, Grabowski EJJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5461–5464. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahm S, Weinreb SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:3815–3818. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Mukaiyama T, Shiina I, Kimura K, Akiyama Y, Iwadare H. Chem. Lett. 1995;24:229–230. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanino K, Shimizu T, Kuwahara M, Kuwajima I. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2422–2423. doi: 10.1021/jo9722358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chelation-controlled Grignard additions of α-hydroxyketones, while relatively uncommon, are known. For an example, see: Matsunaga N, Kaku T, Ojida A, Tasaka A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:2021–2028.

- 18.Yu W, Mei Y, Kang Y, Hua Z, Jin Z. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3217–3219. doi: 10.1021/ol0400342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolaou KC, Yue EW, la Greca S, Nadin A, Yang Z, Leresche JE, Tsuri T, Naniwa Y, de Riccardis F. Chem. Eur. J. 1995;1:467–494. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The product is a (presumably, thermodynamic) mixture of methyl pyranoside and furanoside isomers: β-pyranoside: 62%, α-pyranoside: 34%, β-furanoside: 4%, α-furanoside: <1%.

- 21.Shirahata K, Iida T, Hirayama N. Symposium on the Chemistry of Natural Products. 1981;24:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toshima K, Tatsuta K. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1503–1531. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Ogawa T, Kitajima T, Nukada T. Carbohydr. Res. 1983;123:C8–C11. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(83)88398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hayashi M, Hashimoto S, Noyori R. Chem. Lett. 1984;13:1747–1750. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kihlberg JO, Leigh DA, Bundle DR. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:2860–2863. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sarkar S, Lombardo SA, Herner DN, Talan RS, Wall KA, Sucheck SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17236–17246. doi: 10.1021/ja107029z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Paquette LA, Mitzel TM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:6863–6866. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paquette LA, Mitzel TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:1931–1937. [Google Scholar]; (c) Paquette LA, Lobben PC. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:5604–5616. doi: 10.1021/jo980825f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The highly polar intermediates 24 and 3 were difficult to purify chromatographically, and so were carried through subsequent transformations without purification. We believe that this contributed to the moderate yield of 19 over the three-step sequence.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.