Abstract

The National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) is a cross-sectional survey designed to gather data representative of the UK population on food consumption, nutrient intakes and nutritional status. The objectives of this paper were to identify and describe food consumption and nutrient intakes in the UK from the first year of the NDNS Rolling Programme (2008-09) and compare these with the 2000-01 NDNS of adults aged 19-64y and the 1997 NDNS of young people aged 4-18y. Differences in median daily food consumption and nutrient intakes between the surveys were compared by sex and age group (4-10y, 11-18y and 19-64y). There were no changes in energy, total fat or carbohydrate intakes between the surveys. Children 4-10y had significantly lower consumption of soft drinks (not low calorie), crisps and savoury snacks and chocolate confectionery in 2008-09 than in 1997 (all P< 0.0001). The percentage contribution of non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) to food energy was also significantly lower than in 1997 in children 4-10y (P< 0.0001), contributing 13.7-14.6% in 2008-09 compared with 16.8% in 1997. These changes were not as marked in older children and there were no changes in these foods and nutrients in adults. There was still a substantial proportion (46%) of girls 11-18y and women 19-64y (21%) with mean daily iron intakes below the Lower Reference Nutrient Intake (LRNI). Since previous surveys there have been some positive changes in intakes especially in younger children. However, further attention is required in other groups, in particular adolescent girls.

Keywords: UK, national survey, diet, food, NDNS

As the burden of chronic non-communicable diseases in the United Kingdom (UK) remains high(1-3), diet and nutrition continue to be important public health issues because of their role in prevention(4-6). Cross-sectional UK surveys assessing dietary intake have shown that in all age groups intakes of saturated fatty acids and non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) are above recommended levels(7,8) and that younger adults are more likely than older adults to have low micronutrient intakes(8), for example iron and calcium. Iron intake is especially important in women of child-bearing age as iron deficiency in pregnancy is associated with low birth weight(9), which is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in later life(10). Calcium intake is a determinant of peak bone mass(11) and for ages 11-18y the recommended intake is higher than that in adults as it is a period when the rate of bone mineral deposition is highest(12). Osteoporosis risk is partly determined by peak bone mass therefore the proportion of individuals not meeting recommended calcium intakes presents a potential public health issue. In order to address any nutrition issue at the population level and implement intervention strategies, it is vital that we have a reliable and up-to-date picture of the nation’s diet. The current National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) is a cross-sectional survey of people aged 1.5y and above, designed to be representative of the UK population, which gathers information on food consumption, nutrient intakes and nutritional status(13). It aims to provide data on UK dietary intakes and nutritional status in order to estimate the proportion of individuals meeting recommendations and the proportion with compromised nutritional status. The data feed into policy and are used by the Government to track progress towards existing dietary targets and identify areas that need to be addressed. The data also form the base from which further research or intervention programmes can develop. The NDNS was first set up in 1992 and comprised a series of surveys over the next decade across different age groups(14,7,15). Following a review of this series of surveys(16), it was decided that a Rolling Programme covering all age groups 1.5y and above should be introduced in order to identify and analyse trends more rapidly.

Current dietary guidelines on food consumption set in England and Wales by the Department of Health, in Northern Ireland by the Public Health Agency, and in Scotland by the Scottish Government include recommendations to consume more starchy foods, wholegrain where possible, more fruit and vegetables and less fatty and sugary foods(17-19). Guidelines also exist at the nutrient level based on the 1991 COMA report(12) and state, for example, that intakes of NMES and saturated fats should each contribute no more than 11% food energy. They also state that the population average for non-starch polysaccharide (NSP) intake in adults should be 18g/d.

Over the past ten years there have been a number of programmes aiming to improve diet quality and impact on nutrient intakes, such as the Food and Health Action Plan(20) and the Food in Schools Programme(21) in England and the Scottish Diet Action Plan(22) and Hungry for Success(23) school meals policy in Scotland. The Department of Health’s 5-a-Day programme began in 2000 with a goal to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in the population to at least five 80g portions per day, and improve public awareness about the need to increase fruit and vegetable consumption(24). Against the backdrop of campaigns and healthy eating messages, how has the nation’s diet changed over time and what further action is needed? The objective of this paper is to identify and describe food consumption and nutrient intakes in the UK and compare data from the first year of the Rolling Programme (2008-09) with that from the 2000-01 NDNS of adults aged 19-64y and the 1997 NDNS of young people aged 4-18y to ascertain what changes have occurred over the past decade and compare these with UK recommendations(12,17-19).

Methods

Subjects and study design

The NDNS Rolling Programme is carried out by a consortium of three organisations: the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen), MRC Human Nutrition Research (HNR), and the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at the University College London Medical School (UCL). Fieldwork for the first year of the NDNS Rolling Programme was carried out between February 2008 and March 2009. Fieldwork in England, Scotland and Wales was carried out by NatCen; in Northern Ireland it was carried out by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) in conjunction with NatCen. The sample included 1131 participants aged 1.5-94y and was designed to be representative of the UK population. The survey design and sampling methods are described in detail elsewhere(13). Briefly, a sample of addresses was taken from the UK Postcode Address File of small users (less than 25 items of mail per day). Addresses were clustered into Primary Sampling Units (PSUs), small geographical areas based on postcode sectors, randomly selected from across the UK. Twenty-seven addresses from each PSU were randomly selected and contacted by an interviewer to arrange a face-to-face interview and place a food diary. For nine of these addresses an adult (defined as those aged 19y and above) and a child (defined as those aged 1.5-18y) were selected if available; for the other 18 addresses only children were selected to ensure a large enough sample of children.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Oxfordshire A Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Dietary records

Data were collected using four-day estimated food diaries, including both weekend days. Participants were asked to describe portions using household measures and the diaries included pictures of life-size spoons and a life-size glass to aid accurate recording. Trained interviewers reviewed the diaries with the participants and probed for extra information when necessary. Children 12y and over were encouraged to complete the diaries themselves, while for children below this age the parent/carer was asked to complete the diary. Participants were asked to record food and drinks consumed both at home and away from home, and were therefore asked to take the diary with them when away from home. For young children, a teacher or friend’s parent might then complete parts of the diary for the child. In these situations, carer packs consisting of extra diary pages and an introductory letter were provided for parents to place with other carers of their child. For specific foods consumed in schools where extra details were required for accurate coding, school caterers were contacted for information about recipe information and portion size of dishes. Fifty-five percent of eligible individuals completed three or four dietary recording days. Participants aged 65y and over were not included in the comparison as the total number of participants in this age group in the 2008-09 data was limited. Participants under 4y were also not included as the 1997 NDNS of young people only covered those aged 4-18y. In total, 896 participants from the Rolling Programme aged 4-64y were included in the analysis. The 2000-01 NDNS of adults aged 19-64y included 1724 participants and the 1997 NDNS of young people aged 4-18y included 1701 participants.

Food and nutrient intakes were calculated using DINO (Diet In Nutrients Out), a dietary assessment system developed at HNR, incorporating the Food Standards Agency’s (FSA) NDNS Nutrient Databank(25), which was also used in previous NDNS. The Databank is based on McCance and Widdowson’s Composition of Foods series(26), Food Standards Agency Food Portion Sizes(27), and manufacturers data where applicable. Since the NDNS Rolling Programme began the Databank has been updated by the FSA each year as part of the DH Rolling Programme of Analytical Surveys. Between the previous surveys and the NDNS Rolling Programme, in order to bring the Databank up to date, thousands of foods were removed as they were no longer available. Amendments to the Nutrient Databank are made regularly as a result of queries raised during coding of NDNS diaries and may involve the creation of new food codes for novel or fortified food products, updates to existing food codes relating to manufacturer reformulation, or deletion of food codes due to certain products becoming unavailable. When participants did not know what type of food they had consumed (for example, when food was consumed outside the home), default foods were used; for example, for milk this was semi-skimmed, for fat spread this was reduced fat spread (not polyunsaturated).

Foods were grouped into hierarchical categories and the components of each category are given in Appendix Table 1. The groupings were checking against those from previous surveys to ensure equivalence and were combined where necessary. Nutrient intakes were compared with dietary reference values(12). As in previous NDNS, within the dataset RNI and LRNI values were added for each participant according to their age and sex(12) and corresponding variables for reporting RNI and per cent below LRNI were created. With regard to micronutrient intakes it should be noted that the data used represented the contribution from food only and did not include intake from supplements. Intake from fortified foods was included, as fortified foods are treated in the same ways as all other foods in the nutrient databank, in that they have specific food codes within the databank so that vitamin and mineral values are captured accurately.

Statistical analyses

Food consumption and nutrient intake were analysed by sex and age group (4-10y, 11-18y and 19-64y). Fatty acids were not included in this analysis in detail as they have been analysed and discussed in more detail elsewhere (Pot GK, Prynne CJ, Roberts C, et al, unpublished results*). The data were weighted to account for non-response bias and bias due to differences in the probability of households and individuals being selected to take part and this method is described in detail elsewhere(28). In brief, the weighting factor corrected for known socio-demographic differences between the composition of the survey sample and that of the total population of the UK, in terms of age by sex and Government Office Region. The percentage of participants consuming each particular food group was also calculated. Records of outliers and potential under-reporters were checked for coding errors but were not excluded.

In order to compare intakes from the Rolling Programme with those from previous surveys, which used seven-day food diaries, the 2000-01 and 1997 dietary data were converted to four days (29), using the bootstrapping with replacement method which was run 100 times to reduce potential error caused by variability among participants. Within the sampling frame, the data were re-sampled at random to keep the distribution of the population intact. Each day of the week was equally represented, and consecutive days were chosen for each respondent. Median daily intakes of foods and nutrients were compared using Mann Whitney U tests. The percentage of participants consuming particular foods were compared using χ2 tests. The proportions below the Lower Reference Nutrient Intake (LRNI)(12) for selected micronutrients were compared using χ2 tests. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows (version 14, SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL) and a significance level of P< 0.001 was used throughout to take into account multiple testing of dependent variables.

Results

Study population

Characteristics of the study population such as BMI, socioeconomic status, education level, housing tenure and smoking status are described in detail elsewhere(13). Eleven of the 896 participants provided three rather than four days of dietary data. However there was no difference in the pattern of intake in these individuals when compared with participants who provided four days.

Cereals and cereal products

Tables 1A and 1B show the median daily consumption of foods (including non-consumers) in males and females for all age groups, by survey year. ‘Non-consumers’ refers to participants whose intake for a particular food was 0g and they are included in the calculation of average daily intake. Of all bread consumed, ‘white bread’ remained the largest component and had the largest proportion of consumers in all surveys. However, ‘white bread’ consumption was significantly lower in 2008-09 in boys 4-10y (P< 0.0001), men (P< 0.0001), girls 11-18y (P< 0.0001) and women (P= 0.0004) than in previous surveys. In adults there were no other changes in consumption of cereals and cereal products. Consumption of ‘pasta, rice and other cereals’ (including pizza) was higher in 2008-09 than in 1997 in boys 4-10y, girls 4-10y and boys 11-18y (all P< 0.0001). Median daily consumption of ‘all other breads’ (which includes brown, granary and wheatgerm breads, and 50:50 mixed white and wholemeal breads) was higher in 2008-09 than in 1997 in boys and girls 4-10y (both P< 0.0001), and girls 11-18y (P= 0.0002) but remained a small proportion of all bread consumed. The percentage of children 4-18y consuming ‘all other breads’ in 2008-09 was significantly higher compared with previous surveys (all P< 0.0001), increasing from 24% to 54% in children 4-10y and from 31% to 42% in children 11-18y (data not shown). The median daily consumption of non-high-fibre breakfast cereals was significantly lower in 2008-09 than in 1997 in boys 4-10y (P< 0.0001) and boys 11-18y (P= 0.0003). The percentage of children 4-10y consuming ‘wholegrain and high-fibre breakfast cereals’ was higher in 2008-09 than in 1997 (P< 0.0001, data not shown), rising from 49% to 62%. Biscuit consumption was significantly lower in 2008-09 than in 1997 in boys 4-10y (P= 0.001).

Table 1A.

Median daily consumption of foods (including non-consumersa), males by age and survey year

| Boys 4-10y | Boys 11-18y | Men 19-64y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foods (g/d) | 2008-09 (n=119) |

1997 (n=440) |

2008-09 (n=114) |

1997 (n=416) |

2008-09 (n=181) |

2000-01 (n=833) |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Pasta, rice and other miscellaneous cereals | 70** | 42-122 | 40 | 13-80 | 107** | 58-174 | 60 | 19-116 | 63 | 0-133 | 58 | 0-123 |

| White bread | 27** | 9-60 | 53 | 29-80 | 57 | 27-96 | 70 | 35-109 | 46** | 18-93 | 71 | 28-119 |

| Wholemeal bread | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-34 | 0 | 0-17 |

| Brown, granary and wheatgerm bread/ Other breads | 10** | 0-44 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-22 | 0 | 0-11 | 0 | 0-27 | 0 | 0-32 |

| Wholegrain and high fibre breakfast cereals | 10 | 0-30 | 2 | 0-24 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-23 | 0 | 0-32 |

| Other breakfast cereals | 8** | 0-15 | 14 | 0-30 | 5* | 0-19 | 11 | 0-35 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-9 |

| Biscuits | 13* | 2-21 | 16 | 6-29 | 9 | 0-25 | 11 | 0-26 | 6 | 0-19 | 5 | 0-19 |

| Buns, cakes, pastries and fruit pies | 16 | 0-30 | 20 | 0-40 | 0 | 0-26 | 16 | 0-41 | 5 | 0-25 | 1 | 0-36 |

| Whole milk (3.8% fat) | 0* | 0-191 | 68 | 0-205 | 0** | 0-0 | 0 | 0-87 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-39 |

| Semi skimmed milk (1.8 % fat) | 75 | 0-193 | 0 | 0-152 | 60 | 0-143 | 73 | 0-219 | 60 | 0-143 | 94 | 0-230 |

| Skimmed milk (0.5% fat) | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Cheese | 8 | 0-15 | 3 | 0-12 | 4 | 0-23 | 4 | 0-17 | 11 | 0-30 | 11 | 0-25 |

| Ice Cream | 10 | 0-26 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-17 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Yoghurt, fromage frais and other dairy desserts | 20 | 0-58 | 20 | 0-49 | 0 | 0-31 | 0 | 0-38 | 0 | 0-31 | 0 | 0-31 |

| Eggs and egg dishes | 0 | 0-14 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-29 | 0 | 0-15 | 3 | 0-31 | 13 | 0-34 |

| Butter | 0 | 0-3 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-2 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-2 | 0 | 0-4 |

| Polyunsaturated margarine and oils | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Margarine and other cooking fats and oils, not PUFA | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0** | 0-0 | 0 | 0-2 | 0** | 0-0 | 0 | 0-2 |

| Reduced fat spread | 4 | 0-10 | 2 | 0-8 | 3 | 0-9 | 1 | 0-9 | 4 | 0-12 | 1 | 0-11 |

| Low fat spread | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Bacon and ham | 6 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-11 | 10 | 0-25 | 6 | 0-18 | 13 | 0-25 | 12 | 0-28 |

| Beef, veal and dishes | 12** | 0-44 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-50 | 0 | 0-38 | 23 | 0-89 | 0 | 0-67 |

| Lamb and dishes | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Pork and dishes | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-23 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Coated chicken and turkey | 0 | 0-18 | 0 | 0-18 | 0 | 0-33 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Chicken and turkey dishes | 15** | 0-41 | 5 | 0-23 | 33** | 0-80 | 15 | 0-50 | 35 | 0-101 | 32 | 0-84 |

| Burgers and kebabs | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-10 | 0 | 0-24 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Sausages | 0 | 0-30 | 8 | 0-22 | 0 | 0-30 | 0 | 0-23 | 0 | 0-30 | 0 | 0-20 |

| Meat pies and pastries | 0 | 0-14 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-30 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-34 |

| White fish coated or fried including fish fingers | 0 | 0-21 | 0 | 0-16 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Other white fish, shellfish or fish dishes | 0** | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0** | 0-29 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Oily fish | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0* | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-16 |

| Salad and other raw vegetables | 2 | 0-21 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-22 | 20 | 0-52 | 20 | 0-54 |

| Vegetables (not raw) | 57 | 21-84 | 40 | 15-74 | 54 | 19-91 | 51 | 23-96 | 79 | 38-134 | 90 | 43-149 |

| Chips, fried and roast potatoes and potato products | 38 | 20-61 | 45 | 22-76 | 65 | 33-107 | 70 | 33-112 | 41 | 0-90 | 41 | 0-91 |

| Other potatoes, potato salads and dishes | 21 | 0-45 | 26 | 0-51 | 10** | 0-45 | 35 | 0-70 | 45 | 0-85 | 45 | 0-93 |

| Savoury snacks | 7** | 3-16 | 14 | 6-24 | 11 | 5-20 | 14 | 5-24 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-13 |

| Nuts and seeds | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Fruit | 57 | 35-100 | 49 | 12-97 | 30** | 0-99 | 22 | 0-67 | 60 | 13-142 | 53 | 0-139 |

| Sugars preserves and sweet spreads | 4 | 0-8 | 5 | 0-11 | 2** | 0-11 | 6 | 0-16 | 8 | 0-17 | 10 | 0-27 |

| Sugar confectionery | 0** | 0-8 | 7 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-11 | 0 | 0-14 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Chocolate confectionery | 7** | 0-14 | 13 | 0-25 | 10** | 0-23 | 15 | 0-33 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-14 |

| Fruit juice | 50** | 0-150 | 0 | 0-63 | 0* | 0-142 | 0 | 0-85 | 0 | 0-100 | 0 | 0-65 |

| Soft drinks, not low calorie | 86** | 13-225 | 189 | 64-349 | 292 | 100-500 | 260 | 103-458 | 63 | 0-248 | 31 | 0-165 |

| Soft drinks, low calorie | 75 | 0-272 | 139 | 0-351 | 80 | 0-267 | 65 | 0-265 | 0 | 0-110 | 0 | 0-49 |

| Tea, coffee and water | 150** | 50-330 | 72 | 0-181 | 360** | 190-634 | 150 | 38-374 | 900 | 600-1296 | 928 | 622-1327 |

IQR, interquartile range

median intakes are for the total population (i.e. including participants whose median intake is 0g)

significantly different from previous survey P<0.001

significantly different from previous survey P<0.0001

Table 1B.

Median daily consumption of foods (including non-consumersa), females by age and survey year

| Girls 4-10y | Girls 11-18y | Women 19-64y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foods (g/d) | 2008-09 (n=119) |

1997 (n=397) |

2008-09 (n=110) |

1997 (n=448) |

2008-09 (n=253) |

2000-01 (n=891) |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Pasta, rice and other miscellaneous cereals | 51** | 25-85 | 35 | 10-72 | 74 | 25-139 | 52 | 18-100 | 50 | 5-118 | 45 | 0-89 |

| White bread | 43 | 19-62 | 45 | 26-68 | 37** | 17-69 | 56 | 29-84 | 27* | 9-61 | 43 | 14-78 |

| Wholemeal bread | 0 | 0-5 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-9 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-22 | 0 | 0-18 |

| Brown, granary and wheatgerm bread/ Other breads | 7** | 0-20 | 0 | 0-3 | 0* | 0-24 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-28 | 0 | 0-25 |

| Wholegrain and high fibre breakfast cereals | 8 | 0-18 | 0 | 0-18 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-11 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-28 |

| Other breakfast cereals | 5 | 0-15 | 9 | 0-22 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-18 | 0 | 0-6 | 0 | 0-8 |

| Biscuits | 13 | 4-20 | 17 | 6-28 | 8 | 0-22 | 8 | 0-19 | 8 | 0-19 | 5 | 0-16 |

| Buns, cakes, pastries and fruit pies | 16 | 0-41 | 15 | 0-33 | 6 | 0-21 | 13 | 0-33 | 0 | 0-21 | 5 | 0-30 |

| Whole milk (3.8% fat) | 0 | 0-100 | 52 | 0-162 | 0 | 0-11 | 0 | 0-40 | 0** | 0-0 | 0 | 0-25 |

| Semi skimmed milk (1.8 % fat) | 56 | 0-155 | 3 | 0-112 | 41 | 0-117 | 31 | 0-132 | 70 | 0-136 | 63 | 0-182 |

| Skimmed milk (0.5% fat) | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Cheese | 9 | 0-20 | 6 | 0-15 | 8 | 0-17 | 6 | 0-19 | 8 | 0-20 | 9 | 0-20 |

| Ice Cream | 11 | 0-21 | 0 | 0-19 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Yoghurt, fromage frais and other dairy desserts | 20 | 0-50 | 23 | 0-53 | 0 | 0-30 | 0 | 0-36 | 0 | 0-44 | 0 | 0-39 |

| Eggs and egg dishes | 0 | 0-17 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-28 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-30 | 0 | 0-26 |

| Butter | 0 | 0-3 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-3 | 0 | 0-3 |

| Polyunsaturated margarine and oils | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Margarine and other cooking fats and oils, not PUFA | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0** | 0-0 | 0 | 0-2 | 0* | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Reduced fat spread | 2 | 0-9 | 1 | 0-7 | 3 | 0-9 | 0 | 0-7 | 3 | 0-9 | 0 | 0-6 |

| Low fat spread | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Bacon and ham | 6 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-10 | 6** | 0-13 | 0 | 0-10 | 3 | 0-15 | 5 | 0-16 |

| Beef, veal and dishes | 0 | 0-38 | 0 | 0-22 | 0 | 0-59 | 0 | 0-26 | 14** | 0-89 | 0 | 0-49 |

| Lamb and dishes | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0* | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Pork and dishes | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Coated chicken and turkey | 0 | 0-18 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-8 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Chicken and turkey dishes | 11 | 0-33 | 7 | 0-26 | 20 | 0-70 | 11 | 0-40 | 33* | 0-84 | 23 | 0-62 |

| Burgers and kebabs | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-20 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Sausages | 11* | 0-30 | 0 | 0-16 | 0 | 0-29 | 0 | 0-13 | 0** | 0-15 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Meat pies and pastries | 0 | 0-11 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| White fish coated or fried including fish fingers | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-15 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Other white fish, shellfish or fish dishes | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0** | 0-10 | 0 | 0-0 | 0** | 0-16 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Oily fish | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0* | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-19 |

| Salad and other raw vegetables | 6 | 0-24 | 2 | 0-23 | 8 | 0-22 | 10 | 0-28 | 38* | 12-76 | 28 | 0-65 |

| Vegetables (not raw) | 48 | 29-70 | 40 | 18-71 | 46 | 15-74 | 53 | 24-96 | 89 | 45-150 | 74 | 36-125 |

| Chips, fried and roast potatoes and potato products | 35 | 14-60 | 41 | 20-71 | 41 | 11-84 | 53 | 23-94 | 32 | 0-63 | 28 | 0-60 |

| Other potatoes, potato salads and dishes | 21 | 0-40 | 24 | 0-49 | 30 | 0-50 | 31 | 0-66 | 27** | 0-60 | 45 | 0-86 |

| Savoury snacks | 10** | 3-15 | 15 | 7-24 | 13 | 0-22 | 13 | 05-24 | 0 | 0-10 | 0 | 0-9 |

| Nuts and seeds | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Fruit | 84** | 42-143 | 55 | 19-100 | 42 | 0-88 | 31 | 0-75 | 73 | 25-136 | 70 | 4-163 |

| Sugars preserves and sweet spreads | 3 | 0-9 | 4 | 0-10 | 2** | 0-5 | 4 | 0-12 | 4 | 0-13 | 4 | 0-16 |

| Sugar confectionery | 3 | 0-12 | 6 | 0-19 | 0 | 0-8 | 0 | 0-8 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-0 |

| Chocolate confectionery | 4* | 0-13 | 11 | 0-23 | 6* | 0-17 | 12 | 0-27 | 0 | 0-13 | 0 | 0-13 |

| Fruit juice | 25 | 0-131 | 0 | 0-88 | 0 | 0-88 | 0 | 0-83 | 0 | 0-63 | 0 | 0-63 |

| Soft drinks, not low calorie | 79** | 0-216 | 172 | 65-314 | 195 | 63-333 | 176 | 63-375 | 22 | 0-149 | 0 | 0-121 |

| Soft drinks, low calorie | 41** | 0-237 | 135 | 0-316 | 75 | 20-25 | 58 | 0-222 | 0 | 0-83 | 0 | 0-87 |

| Tea, coffee and water | 253** | 114-530 | 64 | 0-183 | 313** | 120-745 | 199 | 51-417 | 1096* | 705-1510 | 942 | 574-1344 |

IQR, interquartile range

median intakes are for the total population (i.e. including participants whose median intake is 0g)

significantly different from previous survey P<0.001

significantly different from previous survey P<0.0001

Milk and milk products

‘Semi-skimmed milk’ remained the most commonly consumed milk, consumed by 64-75% of participants over the recording period. There was no change in median daily consumption of semi-skimmed milk in any group. ‘Whole milk’ consumption was significantly lower in 2008-09 than in 1997 in boys 4-10y (P= 0.0004), boys 11-18y (P< 0.0001) and women (P< 0.0001) and in these groups represented 44 %, 46% and 21%, respectively, of all milk consumed; this can be attributed to a decrease in the percentage consumers, from 50% to 34% in boys 4-18y and from 31% to 17% in women (both P< 0.0001). There were no changes in median daily consumption of ‘cheese’, ‘ice cream’ and ‘yoghurt, fromage frais and other dairy desserts’.

Fats (spreads)

There was little change in median daily consumption of fat spreads and the most popular remained ‘reduced fat spreads’ (62-75% fat). The percentage consumers of ‘reduced fat spreads’ was significantly higher in children 11-18y and adults in 2008-09 than in previous surveys increasing from 50% to 60% in 11-18y (P= 0.0007) and from 46% to 54% in adults (P= 0.0006) (data not shown).

Meat and meat products and dishes

The most commonly consumed meat food group remained ‘chicken and turkey dishes’, and the median daily consumption was significantly higher in 2008-09 in boys and women rising from 5g to 15g in boys 4-10y (P< 0.0001), from 15g to 33g in boys 11-18y (P< 0.0001), and from 23g to 33g in women (P= 0.0003). ‘Beef, veal and dishes’ was the second most commonly consumed meat group. In women, median daily consumption of ‘beef, veal and dishes’ (P< 0.0001), ‘lamb and dishes’ (P= 0.0006) and ‘sausages’ (P< 0.0001) was significantly higher in 2008-09 compared with 2000-01.

Fish and fish dishes

‘Coated or fried white fish (which includes fish fingers)’ was the most commonly consumed fish group in children 4-10y. ‘Other white fish, shellfish or fish dishes’ (including canned tuna) was the most commonly consumed fish group in children 11-18y and adults. No significant changes were seen in consumption of ‘coated or fried white fish’ in any age group. Since the previous surveys, canned tuna has been reclassified from the food group ‘oily fish’ to the food group ‘other white fish, shellfish or fish dishes’, so it is not possible to assess whether consumption in these groups has changed.

Fruit and vegetables

For girls 4-10y, fruit consumption was significantly higher in 2008-09 than in 1997 (P< 0.0001), with median daily consumption rising from 55g to 84g. Consumption was also significantly higher in boys 11-18y (P< 0.0001) with median daily consumption rising from 22g to 30g. In all groups the percentage of participants consuming fruit was higher compared with previous surveys and this change was greatest in boys 4-10y, increasing from 77% to 91%, and in boys 11-18y, increasing from 56% to 71%, bringing the percentage of boys consuming fruit in line with that in girls (92% girls 4-10y; 71% girls 11-18y). No significant changes were seen in fruit consumption in adults. There were also no significant changes in vegetable consumption or percentage consumers of vegetables in all age groups, apart from in women where median daily consumption of ‘salad and other raw vegetables’ was significantly higher in 2008-09 than in 2000-01 (P=0.0009).

Potatoes

Median daily consumption of ‘other potatoes, potato salads and dishes’ was significantly lower in 2008-09 than in previous surveys in boys 11-18y and women (both P< 0.0001). No other changes were seen in potato consumption.

Sugar, preserves and confectionery and savoury snacks

Significantly lower consumption was seen in 2008-09 compared with 1997 in a number of these foods, particularly in the 4-10y age group. ‘Chocolate confectionery’ consumption was significantly lower in all children (boys 4-10y and 11-18y, both P< 0.0001; girls 4-10y and 11-18y, both P= 0.0002). Consumption of ‘savoury snacks’ was significantly lower in boys and girls 4-10y (both P< 0.0001). Consumption of ‘sugars, preserves and sweet spreads’ (including table sugar) was significantly lower in boys and girls 11-18y (both P< 0.0001). In boys 4-10y, consumption of biscuits (P< 0.001) and sugar confectionery (P< 0.0001) were also significantly lower in 2008-09 than in 1997. No changes in adults were seen for any of these foods.

Beverages

In all groups the percentage of participants consuming fruit juice was higher in 2008-09 compared with previous surveys; most substantially in boys 4-10y, from 41% to 64%. However, median daily consumption of fruit juice remained considerably lower than consumption of other beverages, at below 50g per day. In children 4-10y consumption of ‘soft drinks (not low calorie)’ was significantly lower in 2008-09 than in 1997 (boys and girls, both P< 0.0001) while consumption of ‘fruit juice’ in boys 4-10y (P< 0.0001) and 11-18y (P= 0.0001), and of ‘tea, coffee and water’ in children (all P< 0.0001) and women (P= 0.0002) was significantly higher in 2008-09 than in 1997. For children 4-10y and 11-18y in 2008-09, the largest contributor to the ‘tea, coffee and water’ group was water.

Macronutrients

Tables 2A and 2B show the median daily intakes of macronutrients from food sources in males and females for all age groups, by survey year. There were no significant differences in energy intake in any age/sex group compared with previous surveys. As in the previous surveys total energy intakes were below the Estimated Average Requirements (EARs)(12).

Table 2A.

Median daily intakes of macronutrients from food sources only, males by age and survey year

| Boys 4-10y | Boys 11-18y | Men 19-64y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 (n=119) |

1997 (n=440) |

2008-09 (n=114) |

1997 (n=416) |

2008-09 (n=181) |

2000-01 (n=833) |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Energy (MJ) | 6.595 | 5.709-7.542 | 6.965 | 5.981-8.058 | 8.834 | 7.486-10.330 | 8.687 | 7.325-10.170 | 8.452 | 7.277-10.125 | 8.966 | 7.297-10.449 |

| Energy (kcal) | 1571 | 1354-1788 | 1656 | 1428-1919 | 2092 | 1782-2447 | 2068 | 1743-2419 | 2006 | 1723-2403 | 2130 | 1736-2481 |

| Protein (g) | 56.3* | 48.5-63.0 | 51.3 | 43.3-61.1 | 76.1* | 62.5-87.4 | 69.3 | 56.1-82.5 | 88.8 | 72.3-104.6 | 86.6 | 70.1-102.8 |

| Protein (% food energy) | 14.2** | 13.0-15.8 | 12.5 | 11.2-13.8 | 14.7** | 13.0-16.1 | 13.2 | 11.8-15.1 | 16.8* | 15.0-19.9 | 16.3 | 14.2-18.4 |

| Fat (g) | 61.4 | 47.8-70.6 | 64.3 | 54.3-77.0 | 77.8 | 62.6-99.2 | 81.7 | 66.8-97.5 | 80.1 | 63.6-99.1 | 82.9 | 64.8-103.5 |

| Fat (% food energy) | 34.0 | 30.8-37.8 | 35.6 | 32.7-38.1 | 34.8 | 31.4-38.0 | 35.6 | 32.3-39.0 | 36.0 | 32.0-39.8 | 35.9 | 31.5-39.9 |

| Saturated fatty acids (g) | 23.8** | 18.6-28.2 | 26.5 | 22.0-31.8 | 30.2 | 21.7-38.9 | 32.0 | 25.1-38.7 | 29.2 | 21.7-36.6 | 30.7 | 22.8-40.1 |

| Saturated fat (% food energy) | 13.2** | 11.6-15.0 | 14.6 | 12.9-16.1 | 12.6** | 11.2-14.4 | 13.8 | 12.1-15.5 | 12.9 | 10.9-14.8 | 13.3 | 11.1-15.4 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 215 | 187-249 | 229 | 194-267 | 287 | 226-339 | 280 | 230-330 | 248 | 207-309 | 271 | 215-326 |

| Carbohydrate (% food energy) | 51.2 | 47.9-54.5 | 52.2 | 48.8-54.8 | 50.5 | 46.9-53.8 | 51.2 | 47.1-54.5 | 46.6 | 42.9-50.2 | 48.0 | 43.5-52.4 |

| Starch (g) | 118 | 102-139 | 119 | 101-142 | 157 | 128-181 | 155 | 130-187 | 141* | 112-172 | 153 | 119-190 |

| Starch (% food energy) | 28.8 | 25.3-32.1 | 27.1 | 24.4-30.5 | 28.1 | 24.8-30.9 | 28.5 | 25.5-31.9 | 26.1 | 23.3-29.5 | 27.2 | 23.6-31.1 |

| Total sugars (g) | 93** | 73-115 | 107 | 85-131 | 128 | 91-153 | 119 | 87-156 | 107 | 80-136 | 113 | 79-147 |

| Total sugars (% food energy) | 22.3* | 18.3-26.3 | 24.4 | 20.3-28.0 | 22.0 | 17.5-26.9 | 21.6 | 18.2-26.0 | 20.0 | 15.6-23.4 | 20.2 | 15.6-24.8 |

| Non milk extrinsic sugars (g) | 58** | 42-74 | 74 | 55-94 | 85 | 61-121 | 88 | 60-118 | 67 | 45-86 | 69 | 46-103 |

| NMES (% food energy) | 13.7** | 10.8-17.8 | 16.8 | 13.3-21.0 | 15.5 | 12.2-19.4 | 16.1 | 12.2-19.8 | 12.2 | 8.4-16.1 | 12.4 | 8.6-17.3 |

| Intrinsic and milk sugars (g) | 31 | 26-43 | 31 | 23-40 | 31 | 22-48 | 30 | 21-40 | 36 | 24-51 | 36 | 24-53 |

| IMS (% food energy) | 7.5 | 6.3-10.0 | 7.0 | 5.3-8.8 | 5.7 | 4.1-8.0 | 5.5 | 4.1-6.9 | 6.6 | 4.5-8.8 | 6.4 | 4.6-8.8 |

| Intrinsic and milk sugars and starch (g) |

154 | 134-180 | 151 | 129-177 | 192 | 156-225 | 188 | 157-223 | 178 | 150-224 | 193 | 150-239 |

| IMSS (% food energy) | 37.2** | 33.8-40.2 | 34.2 | 31.6-37.7 | 33.9 | 31.3-38.0 | 34.6 | 31.0-38.0 | 33.3 | 29.6-37.2 | 34.3 | 29.7-39.0 |

| Englyst fibre (g) | 10.8** | 8.5-12.8 | 9.4 | 7.3-11.9 | 12.6 | 9.7-15.8 | 11.7 | 9.5-14.7 | 14.0 | 11.4-18.3 | 14.7 | 10.7-19.2 |

IQR, interquartile range

NMES, non-milk extrinsic sugars

IMS, intrinsic and milk sugars

IMSS, intrinsic and milk sugars, and starch

significantly different from previous survey P<0.001

significantly different from previous survey P<0.0001

Table 2B.

Median daily intakes of macronutrients from food sources only, females by age and survey year

| Girls 4-10y | Girls 11-18y | Women 19-64y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 (n=119) |

1997 (n=397) |

2008-09 (n=110) |

1997 (n=448) |

2008-09 (n=253) |

2000-01 (n=891) |

|||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

| Energy (MJ) | 6.339 | 5.536-7.453 | 6.313 | 5.438-7.234 | 6.985 | 5.808-8.100 | 6.806 | 5.720-8.111 | 6.526 | 5.352-7.784 | 6.548 | 5.388-7.785 |

| Energy (kcal) | 1502 | 1316-1767 | 1501 | 1292-1718 | 1662 | 1379-1915 | 1619 | 1358-1930 | 1553 | 1270-1853 | 1553 | 1281-1850 |

| Protein (g) | 54.5** | 46.1-60.8 | 48.0 | 39.7-56.4 | 59.6** | 49.8-66.1 | 54.1 | 43.7-64.3 | 65.6 | 54.2-79.3 | 63.4 | 51.2-75.1 |

| Protein (% food energy) | 14.3** | 12.8-15.8 | 12.7 | 11.4-14.3 | 14.2** | 12.6-16.0 | 13.2 | 11.6-15.0 | 17.1* | 14.4-19.7 | 16.2 | 13.9-18.7 |

| Fat (g) | 57.8 | 49.7-69.0 | 59.6 | 49.4-70.6 | 67.3 | 52.0-79.7 | 66.2 | 51.6-79.8 | 61.1 | 43.4-77.6 | 60.1 | 45.1-75.2 |

| Fat (% food energy) | 35.5 | 31.8-38.0 | 36.0 | 32.9-39.1 | 36.2 | 33.3-38.6 | 36.1 | 32.7-39.7 | 35.6 | 30.4-39.5 | 34.9 | 30.2-39.4 |

| Saturated fatty acids (g) | 23.3 | 18.7-28.2 | 24.6 | 20.1-29.3 | 23.4 | 18.5-29.4 | 24.8 | 19.7-32.0 | 21.4 | 14.9-28.6 | 22.2 | 16.0-29.4 |

| Saturated fat (% food energy) | 14.0** | 12.3-15.1 | 14.7 | 13.1-16.5 | 13.3* | 11.4-14.6 | 13.8 | 12.1-15.7 | 12.3 | 10.3-14.9 | 13.1 | 10.7-15.2 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 202 | 173-242 | 203 | 173-237 | 219 | 176-254 | 219 | 178-263 | 195 | 158-228 | 202 | 161-245 |

| Carbohydrate (% food energy) | 49.7 | 47.0-53.7 | 51.4 | 47.9-54.3 | 49.7 | 46.7-53.2 | 50.6 | 46.9-54.5 | 47.4 | 43.3-51.9 | 48.8 | 44.2-53.3 |

| Starch (g) | 105 | 95-124 | 104 | 88-125 | 122 | 104-151 | 123 | 99-147 | 111 | 87-131 | 113 | 90-138 |

| Starch (% food energy) | 27.0 | 24.2-29.8 | 26.5 | 23.9-29.4 | 28.7 | 23.9-32.4 | 28.9 | 25.4-32.2 | 26.7 | 23.2-30.5 | 27.2 | 23.6-31.3 |

| Total sugars (g) | 96 | 73-119 | 95 | 77-121 | 94 | 63-115 | 95 | 68-121 | 78 | 61-105 | 85 | 59-115 |

| Total sugars (% food energy) | 23.6 | 19.1-27.7 | 24.5 | 20.4-28.7 | 20.3 | 16.8-24.5 | 21.6 | 17.6-26.1 | 20.0 | 15.9-25.0 | 20.4 | 16.0-25.1 |

| Non milk extrinsic sugars (g) | 57 | 42-84 | 66 | 49-88 | 63 | 43-83 | 67 | 45-91 | 42 | 28-65 | 45 | 27-70 |

| NMES (% food energy) | 14.6** | 10.7-18.0 | 16.8 | 13.0-20.9 | 14.2 | 11.3-17.3 | 15.5 | 11.5-19.6 | 10.7 | 7.7-15.0 | 10.9 | 7.3-15.3 |

| Intrinsic and milk sugars (g) | 34** | 25-44 | 28 | 21-36 | 26 | 18-36 | 24 | 17-34 | 32 | 21-46 | 35 | 23-48 |

| IMS (% food energy) | 8.2** | 6.6-10.6 | 7.1 | 5.5-8.8 | 6.2 | 4.3-8.1 | 5.6 | 4.3-7.4 | 8.0 | 5.5-10.8 | 8.1 | 5.7-11.4 |

| Intrinsic and milk sugars and starch (g) |

137 | 124-162 | 134 | 113-158 | 157 | 127-182 | 149 | 122-180 | 148 | 117-171 | 150 | 121-183 |

| IMSS (% food energy) | 35.4** | 32.7-38.9 | 33.7 | 30.8-37.0 | 34.5 | 30.8-38.2 | 34.9 | 31.0-38.7 | 35.5 | 31.4-39.6 | 36.3 | 31.9-41.4 |

| Englyst fibre (g) | 10.1** | 8.0-12.4 | 8.7 | 6.6-10.8 | 10.5 | 8.5-12.6 | 9.9 | 7.8-12.5 | 12.7 | 9.5-16.0 | 11.9 | 8.8-15.7 |

IQR, interquartile range

NMES, non-milk extrinsic sugars

IMS, intrinsic and milk sugars

IMSS, intrinsic and milk sugars, and starch

significantly different from previous survey P<0.001

significantly different from previous survey P<0.0001

In all age groups, protein as a percentage of food energy was significantly higher in 2008-09 compared with previous surveys (all children P< 0.0001; men P=0.0003; women P= 0.0004). As a percentage of food energy, no changes were seen in total fat or carbohydrate intake, with intakes remaining around the DRVs(12) of 35% and 50%, respectively. A significant decrease in saturated fatty acids as a percentage of food energy was seen in all age groups of children (boys 4-10y and 11-18y, and girls 4-10y, all P< 0.0001; girls 11-18y, P= 0.0001), but this, and changes in intakes of other fatty acids are discussed in detail elsewhere (Pot, G.K., Prynne, C.J., Roberts, C. et al, unpublished results). Intakes of total sugars as a percentage of food energy were significantly lower in boys 4-10y in 2008-09 than in 1997 (P= 0.0008). In children 4-10y, median daily intakes of non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) as a percentage of food energy were lower in 2008-09 than in 1997 (boy and girls, both P< 0.0001), while intakes of intrinsic and milk sugars and starch (IMSS) as a percentage of food energy were higher (boys and girls, both P< 0.0001). No significant changes in NMES or IMSS intake were seen in children 11-18y or adults.

Englyst fibre (NSP) intake was significantly higher in 2008-09 than in 1997 in children 4-10y (boys and girls, both P< 0.0001), increasing from 9.4g to 10.8g per day in boys and from 8.7g to 10.1g per day in girls. No significant changes in NSP intake were seen in children 11-18y and adults.

Micronutrients

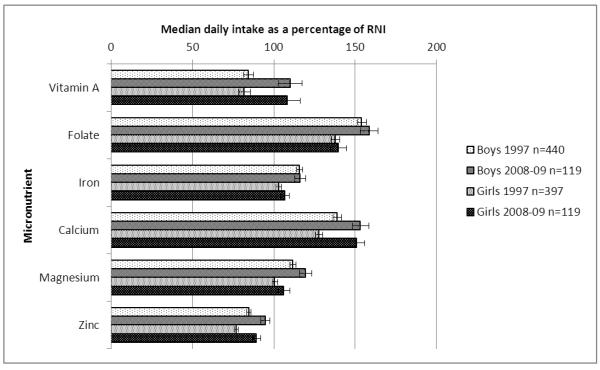

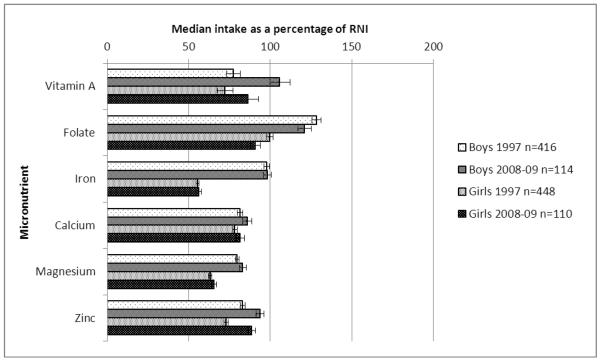

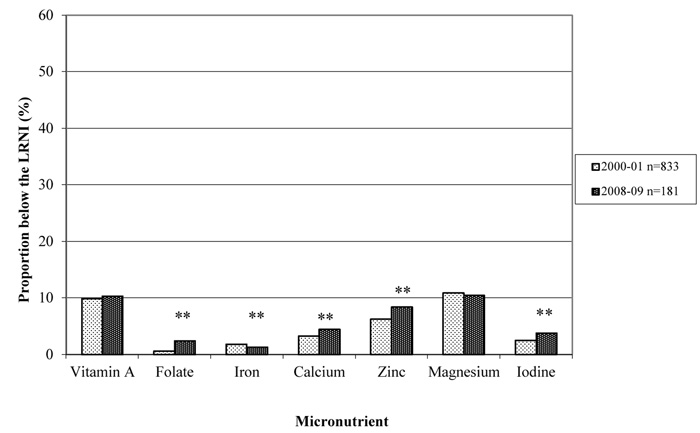

Tables 3A and 3B show median daily intakes of micronutrients from food sources only, in males and females by age and survey year. Changes observed varied among the three age groups. The most consistent change across all age groups was the significantly higher intake of vitamin A in 2008-09 than in previous surveys (all children and women P< 0.0001; men P= 0.0004). Figures 1A and 1B show the median daily intakes of selected micronutrients as a percentage of the Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI)(12) for children 4-10y and 11-18y, by sex and survey year. The figures show that for a number of micronutrients children 11-18y have median daily intakes less than 100% of the RNI, whereas for children 4-10y median daily intakes are greater than or equal to 100% of the RNI for the micronutrients shown. In general, adults also had median daily intakes greater than or equal to 100% of the RNI, apart from intakes of iron, magnesium, potassium and copper in women (data not shown). The 4-10y data are shown as a comparison to the 11-18y data. Median daily intakes of calcium and zinc in girls 11-18y, as a percentage RNI, were higher than in 1997. While median calcium intake was significantly higher in girls 4-10y in 2008-09 compared with in 1997, rising from 653mg/d to 746mg/d (P< 0.0001), it was significantly lower in women in 2008-09 compared with in 2000-01, falling from 761mg/d to 682mg/d (P= 0.0005) (Table 3B). Median daily iodine intake was significantly lower in 2008-09 compared with previous surveys in children 11-18y and adults (boys 11-18y P< 0.0001; girls 11-18y P= 0.0006; men P= 0.0009; women P< 0.0001).

Table 3A.

Median daily intakes of micronutrients from food sources only, males by age and survey year

| Boys 4-10y | Boys 11-18y | Men 19-64y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 (n=119) |

1997 (n=440) |

2008-09 (n=114) |

1997 (n=416) |

2008-09 (n=181) |

2000-01 (n=833) |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Vitamin A (REμg) | 550** | 361-855 | 422 | 306-585 | 639** | 442-1049 | 509 | 338-715 | 785* | 466-1229 | 630 | 434-910 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.3 | 1.0-1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0-1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3-2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3-2.1 | 1.6* | 1.3-2.0 | 1.8 | 1.3-2.3 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.4 | 1.2-1.8 | 1.5 | 1.2-1.9 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.0 | 1.7 | 1.2-2.3 | 1.7** | 1.2-2.2 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.6 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.6 | 1.4-2.1 | 1.8 | 1.4-2.1 | 2.5 | 1.7-3.0 | 2.2 | 1.8-2.9 | 2.5 | 2.1-3.2 | 2.8 | 2.1-3.5 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 3.8 | 2.8-5.1 | 3.7 | 2.9-5.0 | 4.3 | 3.3-5.7 | 4.3 | 3.2-6.0 | 5.6 | 4.0-7.3 | 5.5 | 4.1-7.5 |

| Folate (μg) | 197 | 160-237 | 191 | 159-240 | 242 | 181-320 | 257 | 192-337 | 290* | 227-377 | 330 | 249-423 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 70* | 49-104 | 60 | 40-90 | 82* | 46-125 | 63 | 42-101 | 74 | 51-115 | 71 | 42-116 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 1.8 | 1.2-2.5 | 2.0 | 1.3-2.9 | 2.3* | 1.5-2.9 | 2.5 | 1.8-3.7 | 2.8** | 1.9-3.6 | 3.2 | 2.1-4.9 |

| Iron (mg) | 8.8 | 7.2-10.1 | 8.6 | 7.0-10.6 | 11.1 | 9.1-13.0 | 11.1 | 8.8-13.7 | 11.8* | 9.6-14.3 | 12.6 | 9.6-16.3 |

| Calcium (mg) | 760 | 642-991 | 698 | 564-887 | 860 | 686-1109 | 815 | 602-1022 | 929 | 651-1149 | 986 | 749-1230 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 191 | 169-228 | 180 | 153-218 | 234 | 184-285 | 231 | 184-284 | 290 | 235-361 | 302 | 236-373 |

| Potassium (mg) | 2171 | 1834-2491 | 2016 | 1707-2414 | 2604 | 2139-3276 | 2562 | 2061-3105 | 3257 | 2608-3834 | 3340 | 2717-4032 |

| Zinc (mg) | 6.4** | 5.6-7.5 | 5.7 | 4.7-6.9 | 8.4* | 6.5-9.9 | 7.7 | 6.2-9.3 | 9.8 | 8.1-11.9 | 10.0 | 7.9-11.9 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.8 | 0.6-0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6-0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.4 | 0.9 | 0.7-1.2 | 1.2** | 0.9-1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0-1.7 |

| Iodine (μg) | 133 | 101-184 | 141 | 106-188 | 136** | 96-175 | 158 | 114-220 | 188* | 135-250 | 209 | 155-269 |

IQR, interquartile range

RE, retinol equivalents

significantly different from previous survey P<0.001

significantly different from previous survey P<0.0001

Table 3B.

Median daily intakes of micronutrients from food sources only, females by age and survey year

| Girls 4-10y | Girls 11-18y | Women 19-64y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 (n=119) |

1997 (n=397) |

2008-09 (n=110) |

1997 (n=448) |

2008-09 (n=253) |

2000-01 (n=891) |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Vitamin A (REμg) | 543** | 397-807 | 410 | 291-559 | 519** | 332-776 | 434 | 282-616 | 834** | 510-1294 | 537 | 360-764 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.2 | 0.9-1.4 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.5 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0-1.5 | 1.4 | 1.0-1.7 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.4 | 1.1-1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0-1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8-1.7 | 1.3** | 1.0-1.7 | 1.5 | 1.1-2.0 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.7 | 1.4-1.9 | 1.6 | 1.3-1.9 | 1.8 | 1.4-2.2 | 1.8 | 1.4-2.3 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.4 | 2.0 | 1.5-2.4 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 3.7 | 2.6-4.5 | 3.3 | 2.4-4.3 | 3.4* | 2.5-4.7 | 3.0 | 2.0-4.2 | 4.1 | 2.8-5.4 | 4.3 | 3.0-5.8 |

| Folate (μg) | 174 | 147-215 | 173 | 140-216 | 182 | 150-221 | 199 | 149-257 | 224 | 184-287 | 243 | 182-312 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 68 | 44-106 | 62 | 42-91 | 58 | 42-104 | 61 | 38-94 | 77 | 46-110 | 67 | 41-109 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 1.9 | 1.3-2.4 | 1.7 | 1.2-2.5 | 1.8 | 1.3-2.4 | 1.9 | 1.2-2.8 | 2.3 | 1.3-3.4 | 2.3 | 1.5-3.5 |

| Iron (mg) | 8.0 | 6.8-9.4 | 7.6 | 6.3-9.3 | 8.3 | 6.8-10.2 | 8.2 | 6.6-10.5 | 9.9 | 7.8-12.0 | 9.6 | 7.3-12.2 |

| Calcium (mg) | 746** | 624-909 | 653 | 511-782 | 653 | 534-838 | 626 | 462-823 | 682* | 520-883 | 761 | 581-954 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 183 | 149-210 | 165 | 136-194 | 188 | 157-219 | 183 | 150-223 | 228 | 186-272 | 223 | 178-276 |

| Potassium (mg) | 2016 | 1620-2356 | 1919 | 1549-2258 | 2160 | 1752-2412 | 2091 | 1696-2557 | 2554 | 2120-3032 | 2630 | 2130-3220 |

| Zinc (mg) | 6.0** | 5.1-6.9 | 5.2 | 4.3-6.4 | 6.9** | 5.4-8.2 | 5.8 | 4.6-7.2 | 7.8 | 6.1-9.4 | 7.2 | 5.8-8.9 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.8** | 0.6-0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5-0.8 | 0.9** | 0.7-1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6-0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| Iodine (μg) | 126 | 96-153 | 127 | 92-166 | 100* | 77-138 | 119 | 83-167 | 132** | 95-175 | 151 | 112-198 |

IQR, interquartile range

RE, retinol equivalents

significantly different from previous survey P<0.001

significantly different from previous survey P<0.0001

Fig 1A.

Median daily intakes of selected micronutrients from food sources only as a percentage of RNI in children 4-10y, by sex and survey year. RNI, reference nutrient intake.

Fig 1B.

Median daily intakes of selected micronutrients from food sources only as a percentage of RNI in children 11-18y, by sex and survey year. RNI, reference nutrient intake.

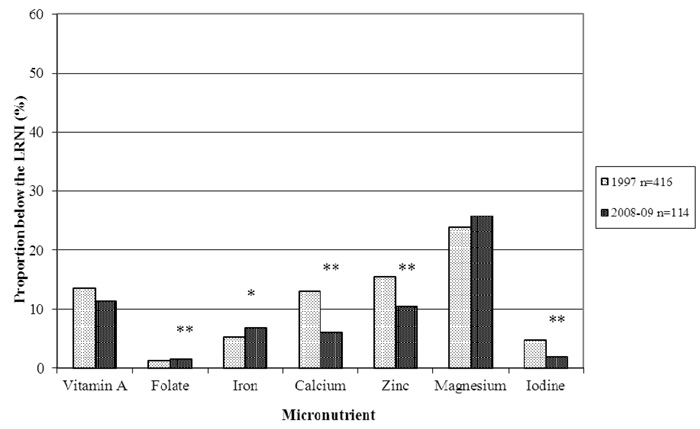

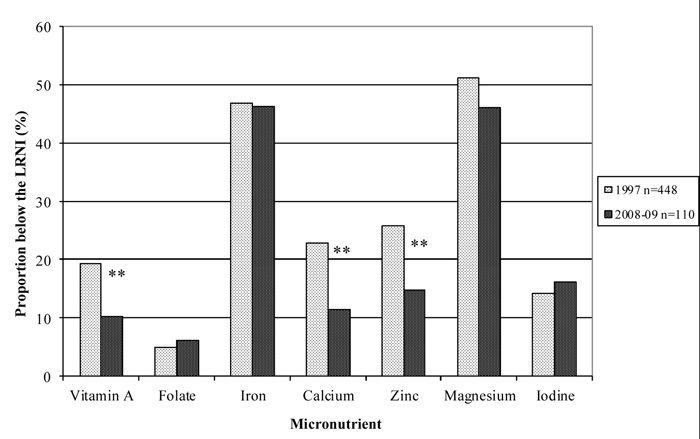

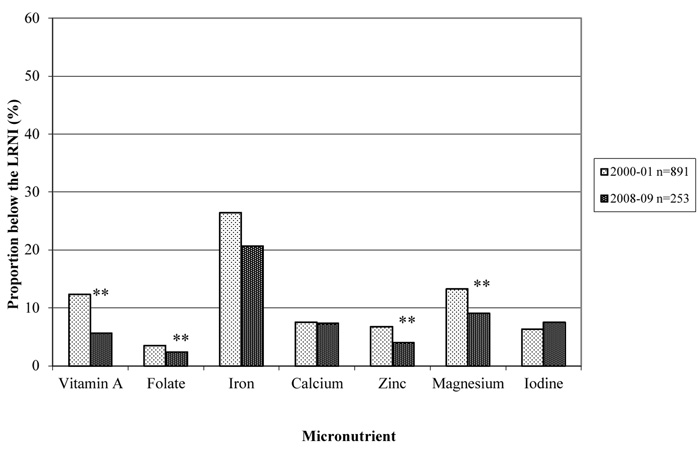

For most age and sex groups, there were fewer than 10% of participants below the LRNI for most micronutrients, in both the 2008-09 data and data from previous surveys. However in the 11-18y age group the proportions below the LRNI were more marked, especially in girls. Figures 2A-2D show the proportion of boys and girls 11-18y, and men and women 19-64y below the LRNI for selected micronutrients from food sources only, by survey year. The proportions of children 11-18y below the LRNI for calcium in 2008-09 were significantly lower than in 1997 (boys and girls both P< 0.0001), falling from 13% to 6% in boys and from 23% to 12% in girls. The proportions of children 11-18y below the LRNI for zinc in 2008-09 were also both significantly lower than in 1997 (boys and girls, both P< 0.0001), falling from 15% to 10% in boys and from 26% to 15% in girls. In men, proportions below the LRNI were slightly higher in 2008-09 compared with in 2000-01 for a number of micronutrients (folate, calcium, zinc and iodine; all P< 0.0001), although all remained no higher than 10%. Conversely, in women, proportions below the LRNI were slightly lower in 2008-09 compared with in 2000-01 for a number of micronutrients (vitamin A, folate, zinc and magnesium; all P< 0.0001). In 2008-09 the proportion of women with intakes below the LRNI for all micronutrients analysed was less than 10%, apart from for iron and potassium, where more than 20% remained below the LRNI. As in 1997, more than 40% of girls 11-18y were below the LRNI for iron. Also as in 1997, in all children 11-18y, a substantial proportion were below the LRNI for magnesium (boys 20%; girls 40%).

Fig 2A.

Proportion of boys 11-18y with mean daily intakes of selected micronutrients from food sources only below the LRNI, by survey year. LRNI, lower reference nutrient intake.

* significantly different from 1997, P<0.001

** significantly different from 1997, P<0.0001

Fig 2B.

Proportion of girls 11-18y with mean daily intakes of selected micronutrients from food sources only below the LRNI, by survey year. LRNI, lower reference nutrient intake.

** significantly different from 1997, P<0.0001

Fig 2C.

Proportion of men 19-64y with mean daily intakes of selected micronutrients from food sources only below the LRNI, by survey year. LRNI, lower reference nutrient intake.

** significantly different from 1997, P<0.0001

Fig 2D.

Proportion of women 19-64y with mean daily intakes of selected micronutrients from food sources only below the LRNI, by survey year. LRNI, lower reference nutrient intake.

** significantly different from 1997, P<0.0001

Discussion

The NDNS is a cross-sectional survey that gathers data on the food consumption, nutrient intakes and nutritional status of people in the UK aged 1.5y and above in order to track progress towards dietary targets and to identify areas that need to be addressed. This analysis has identified changes in food consumption and nutrient intake over the past decade by comparing data from the 2008-09 NDNS Rolling Programme with data from the 2000-01 NDNS of adults aged 19-64y and the 1997 NDNS of young people aged 4-18y. It has shown that for a number of foods and nutrients, there has been little change over time, despite initiatives aimed at improving the nation’s diet, such as the FSA’s public awareness campaign website, ‘Eat Well’(17), and Consumer Focus Scotland’s Healthy Living Award for caterers(30). However, for some foods and nutrients there has been a statistically significant change and this has been in the direction of UK dietary recommendations. These changes were most marked in children 4-10y; for this group, the analysis showed higher intakes of fruit and lower intakes of crisps and savoury snacks, chocolate confectionery and soft drinks (not low calorie). Some changes were seen in children 11-18y but these were not as consistent across the sexes as in children 4-10y. Changes in food consumption are reflected in the nutrient intake data: in younger children the reduction in intakes of NMES, and the higher intakes of NSP, move intakes towards DRVs. For micronutrient intakes, children 4-10y continued to meet recommendations at the population level, while intakes in children 11-18y in general remained below the recommendations – this was especially true for girls, while there was some improvement in boys. However, it is important to point out that micronutrient intakes in girls 11-18y are no worse than in the previous survey; although severely inadequate intakes of micronutrients such as iron were highlighted in this group in 1997, no further reduction has occurred(7).

The strengths and limitations of the present study must be taken into account. The NDNS is the only survey producing nationally representative data on food consumption and nutrient intake in the UK. There are no other similar UK data with which to monitor and investigate dietary trends at the population level. As this is the first year of the Rolling Programme, the sample size of the Year 1 data is smaller than the sample sizes for the previous surveys. However, once Year 1 and Year 2 data are combined, the sample size will be larger and it is possible that some changes that were not detected as significant when analysed for Year 1 only may be evident when data are analysed at the end of Year 2. While the data were weighted it should be noted that the application of non-response weights is not guaranteed to reduce bias for all of the many outcomes and behaviours measured as part of the survey, as weighting is equivalent to replacing members of a subgroup that failed to respond with replicates of responding members of the same subgroup(28).

A limitation inherent to self-reported dietary assessment methods is under-reporting or over-reporting(31), and this may have introduced bias to the data in all of these surveys. Whether the degree of under- and over-reporting is the same in all surveys included here is uncertain. It has been suggested that as awareness of healthy eating increases as a result of public health campaigns, under-reporting of the intake of certain foods may also increase. For example, Heitmann et al(32) hypothesized that observed trends for reductions in fat intakes were actually a result of an increasing trend for under-reporting and that this may be due to an increase in healthy eating campaigns. They found that the degree of under-reporting of total energy in groups of Danish participants was significantly higher in 1993-94 (29%) than in 1987-88 (15%), P< 0.0001. In the present study, if a participant’s intake was flagged as an outlier, their diary was checked against the coded data. If there was a data entry error then this was corrected; otherwise the data were left to reflect what had been recorded in the diary and the participant was not excluded, as it was not considered possible to separate under-reporters from under-consumers (e.g. those who were unwell, for example). Therefore under-reporting has not been accounted for in the present study.

Some of the changes in dietary intake identified could have been a product of the study design, for example, the inclusion of two weekend days in the 2008-09 data. Previous research has shown that haem-to-non-haem iron ratios have been reported to be higher on Sundays than on Saturdays, particularly in adolescents, which suggests a higher level of meat consumption on Sundays(33). The increase in vitamin A seen in most groups in 2008-09 compared with previous surveys may be due to the higher meat consumption seen in most groups. Vitamin A reported as retinol equivalents includes beta-carotene, and, although vegetable consumption has also been shown to be highest on Sundays(34), no changes were seen in vegetable consumption in comparison with previous surveys and hence the increase seen is unlikely to come from vegetable sources. As well as significant day-to-day variation in consumption of certain foods(34,33), the percentage of those consuming a particular food group is also affected by the number of diary days: the longer the recording period the more chance there is that a participant will consume a certain food. The impact of the different recording periods between surveys has been accounted for through the use of the bootstrapping method which means that the direct comparison of percentage consumers is reliable. Selection of diary days in subsequent years of the Rolling Programme has been adjusted so that when data from Year 1 and Year 2 are combined, each day will be equally represented.

Another methodological difference between the surveys was the use of an estimated rather than a weighed food diary in the Rolling Programme. However, it has been shown that there are no significant differences between mean intakes when measured during the same season for weighed and un-weighed food diaries(35). An estimated food diary can also result in better response rates than weighed diaries as the burden to participants is lower. The response rate for Year 1 of the Rolling Programme was 55%, an improvement on the response rate of 47% for the 2000-01 NDNS of adults aged 19-64y.

The continual revision of the FSA’s Nutrient Databank is a significant strength of the present study as it reflects the foods available at the time of fieldwork, through its inclusion of novel foods products and manufacturer reformulations. It is possible that some observed changes in nutrient intake may be due to improved food composition analysis rather than changes in actual intake in the sample. However it is difficult to measure the extent to which this has impacted these results.

The results of the present study have a number of implications for public health. The large proportion of girls 11-18y and women with intakes below the LNRI for iron is of particular concern in that it has not improved since previous surveys. The UK population’s iron intakes have been falling over the past few decades probably owing to changes in the consumption of specific foods, such as the offal meats, liver and kidney, rich sources of iron which are less popular than they were previously(36). Iron deficiency can particularly affect women in the early stages of pregnancy, where iron deficiency anaemia is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight(9), increasing the risk of infant morbidity, infant mortality and cardiovascular disease in later life(10). Iron deficiency is thought to affect up to 50% of women of childbearing age in the UK(37). In the 2000-01 NDNS of adults aged 19-64y, iron deficiency anaemia affected 8% of women(38). Results from the blood sample analysis of the Rolling Programme to be published in 2011 will enable us to determine the proportion of women affected by anaemia.

Calcium intakes in children were higher in 2008-09 than in 1997, and the proportion of children 11-18y with intakes below the LRNI was halved. Since there was no change in semi-skimmed milk consumption, the most commonly consumed milk, and there was no change in the consumption of other dairy products, either in the percentage consumers or the quantity consumed by consumers, this may be due to fortification of certain products, particularly cereal products, although this would need further investigation. Although the increase in calcium intakes is in the right direction, 6% of boys and 12% girls aged 11-18y remained below the LRNI.

More participants in the 2008-09 survey were eating fruit, a change in line with recommendations. This may be as a result of efforts to increase fruit and vegetable consumption and raise awareness through the 5-A-Day initiative(24).

The decrease in intake of soft drinks in younger children was accompanied by an increase in the consumption of the tea, coffee and water group in all children (4-18y), largely a result of increased water consumption. A decrease in soft drink purchases was reported by DEFRA in 2008(39), and this may be associated with the increasing consumer preference for bottled water and the huge investment in advertising from this industry(40), which has made the consumption of bottled water fashionable. While the increase in the consumption of fruit juice was only statistically significant in boys 4-10y, an increase in percentage consumers was seen across all groups. It has been suggested that fruit juice consumption is a marker for healthier dietary habits(41), and, although some studies have found an association between weight and fruit juice consumption in children(42,43), one did not specify whether ‘fruit juice’ referred to 100% fruit juices or fruit juice drinks, and the other used a small regional sample. Studies using large nationally representative samples have produced results to the contrary(44,45), such as the secondary analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey by Nicklas et al, published in 2008(44), which found that in US children aged 2-11y, consuming 100% fruit juices was associated with significantly higher intakes of vitamin C and B6, potassium, magnesium, riboflavin, iron and folate and lower intakes of total fat, SFA and added sugar. They also found that it was not associated with weight status or the likelihood of being overweight in these children. Thus, the increase in fruit juice consumption in children in the Rolling Programme should be seen as a positive change in the right direction.

The lower contribution of NMES to food energy in children 4-10y is another change in the direction of dietary recommendations. A cross-sectional study carried out in 2000 of 11-12–year-olds across seven schools in Northumberland showed that school meals were a substantial contributor to NMES intakes, with biscuits, cakes and soft drinks being the main sources(46). Since the 1997 NDNS of young people aged 4-18y, there have been various efforts throughout the UK to improve the nutritional quality of school meals. National Nutritional Standards were introduced in schools in England in 2001(47) and, following this, over £280 million was invested to improve school meals(48). The Hungry for Success policy for school meals in Scotland was implemented in 2002 and includes HMIE inspections making the measures compulsory and, according to the 2008 HMIE report, most schools were moving towards achieving the nutrient standards set(49). The school fruit and vegetable scheme (SFVS) in England, introduced in 2004, consisted of a free piece of fruit or vegetable being provided every day to children aged 4-6y. A non-randomised controlled trial published in 2007(50) evaluating this scheme found that it was associated with an increase in 0.4-0.5 portions/d of fruit at three months, but that after seven months the effect was reduced to an increase of 0.3 portions/d. While this is a modest change, it shows that the scheme has been effective in increasing fruit consumption in this age group. In 2007, the school nutrient standards in England were updated to cover food available in schools besides lunches, including vending machines and tuck shops. A number of foods were no longer permitted in vending machines such as soft drinks containing less than 50% fruit juice, and confectionery including chocolate and sweets(51). This would suggest that all food available in schools is now healthier and more likely to meet recommendations than in 1997, and may explain why most change was seen in younger children. In secondary schools, many children have the option to leave the school for lunch and in 2008-09 in England approximately 65% of children in secondary schools, academies and city technology colleges chose not to take school meals(52). In Scotland in 2008 approximately 54% of children chose not to take school meals(49). In addition to improvements in schools, access to and availability of healthier choices may have had some impact. The food industry often uses the potential health benefits of foods to market their products, and the 5-A-Day message is often present on advertisements. Low sugar/sugar-free options are also more widely available, creating an environment where consumers are more likely to make healthier choices. However, as this analysis has compared repeated cross-sectional surveys, it is not possible to attribute the changes seen to specific national policies or interventions, and further work would be required to do this.

In conclusion, while the positive changes seen are modest in most groups except younger children, it is important to note that across the board they are predominantly changes in the right direction. Furthermore, there are no dietary problem areas that have worsened. Continued monitoring of trends through the continuation of the NDNS Rolling Programme will allow further and more thorough comparisons to be made. More efforts are needed to improve the diets of older children, especially girls, and future campaigns should target this group specifically.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Operations Team at NatCen and all interviewers involved for the collection of data; statisticians Dr Adrian Mander and Mark Chatfield for contributions to the survey design; and Melanie Farron-Wilson and Mary Day at the Food Standards Agency for contributions to food composition issues. We also thank all participants of the survey for providing their dietary information.

C.W. analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. A.M.S., G.S., B.B., B.T., H.H. and C.R. designed, coordinated and supervised the survey. C.W., G.P. and A.O. prepared data for analysis. S.K.N., C.R., C.J.P., G.P. and A.S contributed to the interpretation of results and editing of the manuscript. S.P. and C.D. contributed to survey design and data collection. E.F. coordinated food composition data. D.C. designed the nutrient analysis software. A.O. provided statistical guidance and contributed to editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft before publication. No authors have a conflict of interest to declare. NDNS is funded by the Food Standards Agency and the Department of Health.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Hierarchical categories food type, food groups and sub food group

| Food Type | Food Group | Sub Food Group |

|---|---|---|

|

Cereals and cereal products |

Pasta, rice and other miscellaneous cereals |

-Pizza -Pasta manufactured products & ready meals -Other pasta including homemade dishes - Rice manufactured products and ready meals - Other rice including homemade dishes - Other cereals |

| White bread | - White bread (not high fibre; not multiseed bread |

|

| Wholemeal bread | - Wholemeal bread | |

| All other breads | - Brown bread - Granary bread - Wheatgerm bread - Other bread |

|

|

Wholegrain and high fibre breakfast cereals |

- Wholegrain and high fibre breakfast cereals | |

| Other breakfast cereals | - Other breakfast cereals (not high fibre) | |

| Biscuits | - Biscuits manufactured / retail - Biscuits, homemade |

|

|

Buns, cakes, pastries and fruit pies |

- Fruit pies manufactured - Fruit pies homemade - Buns cakes and pastries manufactured - Buns cakes & pastries homemade |

|

|

Milk and milk products |

Whole milk | - Whole milk |

| Semi skimmed milk | - Semi skimmed milk | |

| Skimmed milk | - Skimmed milk | |

| Other milk and cream | - Infant formula - Cream (including imitation cream) - Other milk |

|

| Cheese | - Cottage cheese - Other cheese |

|

|

Yogurt, fromage frais and other dairy desserts |

- Yogurt - Fromage frais and other dairy desserts manufactured - Dairy desserts homemade |

|

| Ice cream | ||

|

Eggs and Egg dishes |

Eggs and egg dishes | - Manufactured egg products including ready meals - Other eggs and egg dishes including homemade |

| Fat spreads | Butter | - Butter |

|

Polyunsaturated margarine and oils |

- Polyunsaturated margarine - Polyunsaturated oils |

|

| Low fat spread | - Polyunsaturated low fat spread - Low fat spread not polyunsaturated |

|

|

Margarine and other cooking fats and oils NOT polyunsaturated |

- Block margarine - Soft margarine not polyunsaturated - Other cooking fats and oils not pufa |

|

| Reduced fat spread | - Reduced fat spread (polyunsaturated) - Reduced fat spread (not polyunsaturated) |

|

|

Meat and meat products |

Bacon and ham | - Ready meals / meal centres based on bacon and ham - Other bacon and ham including homemade dishes |

| Beef, veal and dishes | - Manufactured beef products including ready meals - Other beef & veal including homemade recipe dishes |

|

| Lamb and dishes | - Manufactured lamb products including ready meals - Other lamb including homemade recipe dishes |

|

| Pork and dishes | - Manufactured pork products including ready meals - Other pork including homemade recipe dishes |

|

|

Coated chicken and turkey |

- Manufactured coated chicken / turkey products | |

|

Chicken and turkey dishes |

- Manufactured chicken products incl ready meals - Other chicken / turkey incl homemade recipe dishes |

|

| Burgers and kebabs | - Burgers and kebabs purchased | |

| Sausages | - Ready meals based on sausages - Other sausages including homemade dishes |

|

| Meat pies and pastries | - Manufactured meat pies and pastries - Homemade meat pies and pastries |

|

|

Other meat and meat products |

- Other meat products manufactured incl ready meals - Other meat including homemade recipe dishes |

|

|

Fish and fish dishes |

White fish coated or fried including fish fingers |

- White fish coated or fried |

|

Other white fish, shellfish and fish dishes |

- Manufactured white fish products incl ready meals - Other white fish including homemade dishes - Manufactured shellfish products incl ready meals - Other shellfish including homemade dishes |

|

| - Manufactured canned tuna products incl ready meals - Other canned tuna including homemade dishes |

||

| Oily fish | - Manufactured oily fish products incl ready meals - Other oily fish including homemade dishes |

|

|

Vegetables, potatoes & savoury snacks |

Salad and other raw vegetables |

- Carrots (raw) - Salad and other raw vegetables - Tomatoes raw |

| Vegetables (not raw) | - Peas not raw - Green beans not raw - Baked beans - Leafy green vegetables not raw - Carrots not raw - Tomatoes not raw - Beans and pulses incl ready meal & homemade dishes - Meat alternatives incl ready meals and & homemade dish - Other manufactured vegetable products incl ready meals - Other vegetables including homemade dishes |

|

|

Chips, fried and roast potatoes and potato products |

- Chips purchased including takeaway. - Other manufactured potato products fried/baked - Other fried / roast potatoes incl homemade dishes |

|

|

Other potatoes, potato salads and dishes |

- Other potato products & dishes, manufactured - Other potatoes including homemade dishes |

|

|

Crisps and savoury snacks |

- Crisps and savoury snacks | |

| Fruit | Fruit | - Apples and pears not canned - Citrus fruit not canned - Bananas - Canned fruit in juice - Canned fruit in syrup - Other fruit not canned |

|

Sugar, preserves and confectionery |

Sugars preserves and sweet spreads |

- Sugar - Preserves - Sweet spreads fillings and icing |

| Sugar confectionery | - Sugar confectionery | |

| Chocolate confectionery | - Chocolate confectionery | |

| Total beverages1 | Fruit juice | - Fruit juice (100%) |

| Soft drinks, not diet | - Soft drinks not low calorie concentrated2 - Soft drinks not low calorie carbonated - Soft drinks not low calorie RTD still |

|

| Soft drinks, diet | - Soft drinks low calorie concentrated2 - Soft drinks low calorie carbonated - Soft drinks low calorie RTD still |

|

| Spirits and liqueurs | - Liqueurs - Spirits |

|

| Wine | - Wine - Fortified wine - Low alcohol and alcohol free wine |

|

|

Beer lager cider and perry |

- Beers and lagers - Low alcohol & alcohol free beer & lager - Cider and perry - Low alcohol & alcohol free cider & perry - Alcoholic soft drinks |

|

| Tea, coffee and water | - Coffee (made-up weight) - Tea (made up) - Herbal tea (made up) - Bottled water still or carbonated - Tap water only |

Food type ‘beverages’ excludes powdered malted and chocolate type beverages.

Report consumption of concentrated soft drinks as made up

Footnotes

Submitted to the British Journal of Nutrition on 25/10/2010. Pot GK, Prynne CJ, Roberts C, et al. (2010) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Fat and fatty acid intakes from the first year of the rolling programme and comparison with previous surveys.

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Craig R, Mindell J. Health Survey for England 2006. Volume 1. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in adults. 2008 http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/HSE06/HSE%2006%20report%20VOL%201%20v2.pdf (accessed September 2010)

- 2.Bromley C, Bradshaw P, Given L. Scottish Health Survey 2008. Volume 1: Main Report. 2009 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/286063/0087158.pdf (accessed September 2010)

- 3.Haines L, Wan KC, Lynn R, et al. Rising incidence of type 2 diabetes in children in the U.K. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1097–1101. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khaw K-T, Bingham S, Welch A, et al. Blood pressure and urinary sodium in men and women: the Norfolk Cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC-Norfolk) Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1397–1403. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L, et al. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk. The Framingham experience. AMA Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1867–1872. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory JR, Lowe S, Bates B, et al. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: young people aged 4 to 18 years. 2000. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swan G. Findings from the latest Nation Diet and Nutrition Survey. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:505–512. doi: 10.1079/pns2004381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholl TO, Hediger ML. Anemia and iron-deficiency anemia: compilation of data on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:492S–500S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.2.492S. discussion 500S-501S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ. 1990;301:1111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Prevention and management of osteoporosis. Technical Report Series 921. 2003 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/who_trs_921.pdf (accessed Feb 2011) [PubMed]

- 12.Department of Health . Report on health and social subjects No. 41. HMSO; London: 1991. Dietary reference values for food energy and nutrients for the United Kingdom. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates B, Lennox A, Swan G. NDNS Headline results from Year 1 of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009) 2010 http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/publication/ndnsreport0809year1results.pdf (accessed July 2010)

- 14.Gregory J, Collins DL, Davies PSW, et al. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: children aged 1 1/2 to 4 1/2 years. Volume 1. Report of the diet and nutrition survey. 1995. accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoare J, Henderson L, Bates CJ, et al. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: adults aged 19 to 64 years. Volume 5: Summary report. 2004 http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/ndns5full.pdf (accessed August 2010)

- 16.Ashwell M, Barlow S, Gibson S, et al. National Diet and Nutrition Surveys: the British Experience. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:523–530. doi: 10.1079/phn2005874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food Standards Agency Healthy diet. 8 tips for eating well. 2010 http://www.eatwell.gov.uk/healthydiet/eighttipssection/8tips/ (accessed 10th June 2010)

- 18.The Scottish Government Dietary Targets. 2006 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Health/health/19133/17756 (accessed September 2010)

- 19.Public Health Agency Nutrition. 2010 http://www.enjoyhealthyeating.info/primarylinks/nutrition (accessed Sept 2010)

- 20.Do Health Choosing a better diet: a food and health action plan. 2005 Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4105709.pdf (accessed July 2010)

- 21.Health DDo Food in schools programme. 2010 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthimprovement/Foodinschoolsprogramme/index.htm (accessed June 2010)

- 22.S Executive Eating for health - meeting the challenge. 2004 Available at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/47060/0012960.pdf (accessed June 2010)

- 23.S Executive . A whole school approach to school meals in Scotland. TSO; 2002. Hungry for success. Available at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2003/02/16273/17566 (accessed June 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health Five-a-day Update. 2001 http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4074293.pdf (accessed July 2010)

- 25.Smithers G. MAFF’s Nutrient Databank. Nutrition & Food Science. 1993:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food Standards Agency . McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods. 6th ed. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Food Standards Agency . Food Portion Sizes. 3rd ed. TSO; London: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Food Standards Agency Appendix B Weighting the NDNS core sample. 2010 http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/publication/ndns0809appendixb.pdf (accessed July 2010)

- 29.Food Standards Agency Appendix K Conversion of previous survey data to four-day estimates. 2010 http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/publication/ndns0809appendixk.pdf (accessed 1st March 2010)

- 30.Consumer Focus Scotland Healthy Living Award. 2010 http://www.healthylivingaward.co.uk/index.asp (accessed Oct 2010)