Abstract

We developed a flow cytometry-based assay to simultaneously quantify multiple leukocyte populations in the marginated vascular, interstitial, and alveolar compartments of the mouse lung. An intravenous injection of a fluorescently labeled anti-CD45 antibody was used to label circulating and marginated vascular leukocytes. Following vascular flushing to remove non-adherent cells and collection of broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, lungs were digested and a second fluorescent anti-CD45 antibody was added ex vivo to identify cells not located in the vascular space. In the naïve mouse lung, we found about 11 million CD45+ leukocytes, of which 87% (9.5 million) were in the vascular marginated compartment, consisting of 17% NK cells, 17% neutrophils, 57% mononuclear myeloid cells (monocytes, macrophage precursors and dendritic cells), and 10% T cells (CD4+, CD8+, and invariant NKT cells). Non-vascular compartments including the interstitial compartment contained 7.7 × 105 cells, consisting of 49% NK cells, 25% dendritic cells, and 16% other mononuclear myeloid cells. The alveolar compartment was overwhelmingly populated by macrophages (5.63 × 105 cells, or 93%). We next studied leukocyte margination and extravasation into the lung following acid injury, a model of gastric aspiration. At 1 hour after injury, neutrophils were markedly elevated in the blood while all other circulating leukocytes declined by an average of 79 percent. At 4 hours after injury, there was a peak in the numbers of marginated neutrophils, NK cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and a peak in the number of alveolar NK cells. Most interstitial cells consisted of DCs, neutrophils, and CD4+ T cells, and most alveolar compartment cells consisted of macrophages, neutrophils, and NK cells. At 24 hours after injury, there was a decline in the number of all marginated and interstitial leukocytes and a peak in alveolar neutrophils. In sum, we have developed a novel assay to study leukocyte margination and trafficking following pulmonary inflammation and show that marginated cells comprise a large fraction of lung leukocytes that increases shortly after lung injury. This assay may be of interest in future studies to determine if leukocytes become activated upon adherence to the endothelium, and have properties that distinguish them from interstitial and circulating cells.

Keywords: Flow cytometry, in vivo trafficking, marginated leukocytes, pulmonary leukocytes

1. Introduction1

The trafficking of cells in response to infection and tissue injury is critical to the immune response. One compartment of cells that has not been well studied consists of cells adhered to the endothelium of blood vessels, or “marginated” to the vascular wall. In the naïve lung, large pools of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes appear to be marginated based on in vivo videomicroscopy (Gebb et al., 1995). During inflammation, pre-marginated cells, as well as other immune cells that rapidly leave the circulation and adhere to endothelial cells, can undergo both transendothelial and transepithelial migration into the interstitial and alveolar spaces, respectively. Several recent studies have highlighted the importance of intravascular immunity, whereby immune cells patrol the blood vessels for pathogens to prevent dissemination of bacteria or viruses (Mizgerd et al., 1996; Doyle et al., 1997). In the lung, marginated cells are poised to rapidly enter the interstitium in response to infection or injury. These sentinel cells may constitutively roll along the endothelium as they participate in immune surveillance. Marginated cells are therefore highly distinct from the non-adhered leukocytes found in blood. In this study we consider the blood compartment to consist only of non-adherent cells, excluding cells marginated to the vascular wall.

A standard method for detecting immune cells in the lung involves flow cytometric analysis of cells prepared from enzymatically-dispersed tissue and from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Quantitation can also be based on immunohistological images. Cells classified as circulating generally do not include marginated cells that are adhered to the endothelium and do not appear in blood samples. Most studies of tissue leukocytes do not distinguish between marginated vascular and interstitial cells, since both are released when tissues are enzymatically digested. T cells labeled ex vivo with radioactive or fluorescent dyes accumulate in the lung shortly after adoptive transfer. (Kubes and Kerfoot, 2001; Galkina et al., 2005; Hickey and Kubes, 2009). This approach enables the kinetics of T cell accumulation in tissues to be determined, but does not distinguish between interstitial cells and vascular marginated cells. One study used IV injection of a fluorescently tagged anti-neutrophil (anti-GR-1) antibody for a short time to selectively label intravascular PMNs (Reutershan et al., 2005). The vasculature was then flushed with saline to remove all non-adherent cells, and bronchoalveolar lavage was performed to collect alveolar neutrophils. Flow cytometry was used to distinguish marginated PMNs (labeled with fluorescent intravenous GR-1 antibody) from interstitial and alveolar PMNs. We set out to design a similar method for identifying all CD45+ leukocyte subsets in lung compartments at baseline and after acid injury which has been used as a model of lung injury due to gastric aspiration (Kennedy et al., 1989; Knight et al., 1992; Reutershan et al., 2005; Nemzek et al., 2010). The results indicate that a surprisingly large fraction of lung leukocytes (87%) are marginated to the walls of blood vessels in the uninjured lung, and this fraction becomes even larger within 1–4 hours of acid injury. Previous studies of acid-induced lung injury described a biphasic time course of leukocyte uptake into the lungs, with peaks of cells at 1 and 4 hours post-acid injury, as compared to control animals that received intra-tracheal saline (Nagase et al., 2000; Imai et al., 2005; Zarbock et al., 2006; Matute-Bello et al., 2008). The 4 hour peak was characterized by a marked influx of neutrophils into the pulmonary interstitial space (Kennedy et al., 1989). A more recent study characterized the mechanism of neutrophil recruitment in acid-induced injury. Kennedy et al. (1989) demonstrated that P-selectin dependent interactions between activated platelets and neutrophils promote neutrophil recruitment and lung damage after acid injury. In the current study we show that, with the exception of neutrophils, there is a 50–90% decrease in blood levels of all leukocytes within 1 hour of acid injury, and increases in the numbers of marginated lung vascular T cells, NK cells and neutrophils from 1 to 4 hours after injury. In addition, we found that the marginated population of all leukocytes exceeds the interstitial population during most of the inflammatory response. Taken together, our data suggest that the leukocyte compartment assay can distinguish between leukocyte compartments within the lung, and can reveal new information about the large fraction of marginated cells that is transiently increased in response to lung injury.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Rat anti-mouse CD45 antibody (clone 30-F11) labeled with PE-Cy7 was obtained from eBioscience and used for intravenous injection. Rat anti-mouse CD45 antibody (ATCC TIB122, clone M1/9.3.4.HL.2) was expanded by the University of Virginia Lymphocyte Culture Center and labeled with a DyLight® 405 antibody labeling kit (Pierce) and used for ex vivo leukocyte labeling. Reagents used to identify specific cells were from eBioscience unless otherwise noted: the αGalCer-analog (PBS57) loaded or unloaded APC-labeled CD1d tetramer (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Tetramer Facility), FITC-labeled anti-NKp46 (R&D), FITC-labeled anti-CD45, PE-labeled anti-Ter119, PE-labeled anti-CD8α, PerCP-labeled anti-CD4, APC-Alexa Fluor 750-labeled anti-CD3ε, FITC-labeled anti-MHC Class II, PE-labeled anti-CD115, PE-labeled anti-Mac3, PerCP-labeled anti-GR-1, APC-labeled anti-CD11b, APC-Alexa Fluor 750-labeled anti-CD11c. Several experiments also incorporated the fixable AQUA Live/Dead viability dye (Invitrogen).

2.2. Mouse Model

Mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care & Use Committee of the University of Virginia. Eight- to twelve-week old male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. To induce acid injury, a tracheal cut-down was performed and 30 μL of 0.1M hydrochloric acid was injected followed by 20 μL of air. Mice were immediately placed upright at 45 degrees to promote inhalation of acid. Tracheal wounds were closed using topical liquid adhesive (Nexaband®) and mice were placed under a heating lamp during recovery from anesthesia. Naïve NY1DD sickle cell mice with a known pulmonary vascular leak (Wallace et al., 2009) (gift from R. Hebbel, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN) on a C57BL/6 background were used as a positive control for pulmonary vascular permeability measured by Evans blue dye (EBD).

2.3. Leukocyte Compartment Assay

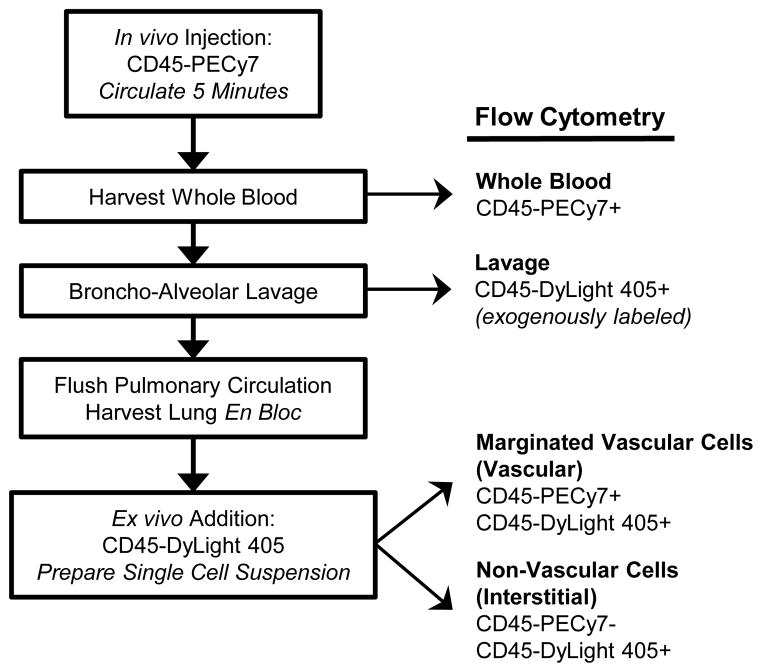

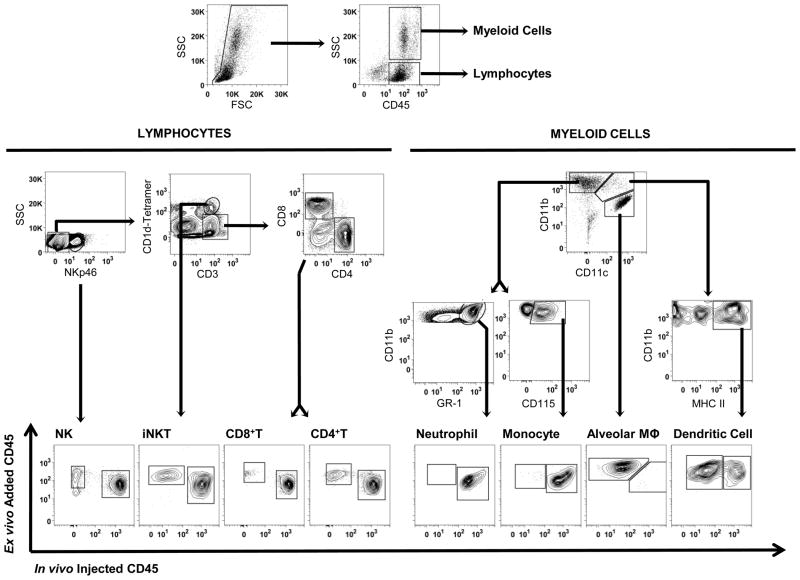

The leukocyte compartment assay and flow cytometry gating strategies are summarized in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The technique relies on the binding of distinct anti-CD45 antibodies, one that is added intraveneously, and a second that is added to lung single cell suspensions. The first antibody only labels cells in the vascular space, including circulating cells and cells that are adhered to the endothelium. The second antibody recognizes a distinct epitope and labels all CD45+ leukocytes. As illustrated in Figure 2, in the uninjured lung almost all neutrophils and monocytes are found in the vascular space, and almost all alveolar macrophages are found in the non-vascular space, whilce other leukocytes are divided between these compartments.

Fig 1.

Leukocyte compartment assay schematic.

Fig 2.

Gating strategy for leukocyte compartment assay. Cells were dispersed from mouse lungs, and single cells (singlets, low pulse width) were divided into lymphoid (low SSC) and myeloid (high side scatter, SSC) sub-populations. Lymphoid cells were sub-classified as NK cells (CD3ε− NKp46+), invariant NKT cells (CD3ε+ CD1d-tetramer+), CD8+ T cells (CD3ε+ CD1d-tetramer− CD8α+), and CD4+ T cells (CD3ε+ CD1d-tetramer− CD4+). The CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets do not include iNKT cells. Myeloid cells were sub-classified as neutrophils (CD11b+ CD11c− GR-1+), inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+ CD11c− CD115+), inflammatory mononuclear cells (CD11b+ CD11c− Mac3+ macrophages; gate not shown for simplicity), alveolar macrophages (CD11b− CD11c+ autofluorescent+ MHCII+; sub-gates not shown for simplicity), and dendritic cells (CD11b+ CD11c+ MHC Class II+). Each leukocyte subset was further classified as marginated vascular (in vivo injected CD45-PECy7+ ex vivo CD45-DyLight 405+) or interstitial (in vivo injected CD45-PECy7− ex vivo CD45-DyLight 405+). Blood and lavage samples were analyzed similarly, but separately (not shown).

2.3.1. In vivo labeling of vascular leukocytes

Anesthetized mice were injected with 10 μg/100 μL PE-Cy7-labeled rat anti-CD45 antibody via the retro-orbital venous plexus. The antibody was allowed to circulate for 5 minutes prior to euthanasia in order to label all leukocytes in the vascular space. This includes circulating blood leukocytes (“blood compartment”) and leukocytes marginated to the vasculature wall (“marginated vascular compartment”).

2.3.2. Whole blood and bronchoalveolar lavage harvest

The chest was opened and a left ventricular heart puncture was performed with a heparinized syringe to collect whole blood for analysis. The volume of blood collected from each animal was measured. The trachea was cannulated and lavage was performed 5x with 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mM EDTA. Whole blood and lavage fluid were placed on ice for subsequent staining for flow cytometry (Section 2.3.5). The descending aorta was transected and then the lung vasculature was perfused via the right ventricle with 10 mL PBS.

2.3.3. Ex vivo labeling of non-vascular (interstitial) pulmonary leukocytes

Lungs were removed en bloc and minced with surgical scissors in the presence of 100 μg/100 μL DyLight® 405-labeled anti-CD45 antibody to exogenously label all pulmonary leukocytes. This included marginated pulmonary vascular leukocytes and non-vascular (interstitial) pulmonary leukocytes.

2.3.4. Tissue Preparation

Lung cells were prepared using reagents purchased from Sigma. Minced lungs were placed in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 60 units/mL DNase 1 and 0.1 mg/mL Kunitz-type soybean trypsin inhibitor. Once all lungs were harvested and minced,1 mg/mL type XI collagenase was added to each minced lung and tissues were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Digested lungs were passed through a 40 μm filter to generate single cell suspensions. The addition of trypsin inhibitor and delayed addition of collagenase were found to be necessary to prevent degradation of antibodies during lung digestion.

2.3.5. Immunostaining of Leukocytes for Flow Cytometry

Cells were counted (Countess Cell Counter, Invitrogen), resuspended in 1% BSA-PBS staining buffer, and Fcγ receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/CD32 (eBioscience). Cells were stained for extracellular antigens to define leukocyte subsets with the antibodies described above (Section 2.1). Whole blood, lung, and lavage samples were labeled and analyzed separately, and were gated using fluorescence minus one (FMO) analysis and isotype controls as shown in Figure 2. This technique excluded any autofluorescent cells. Marginated leukocytes were defined as double positive for CD45-PECy7 and CD45-DyLight® 405; interstitial leukocytes including lymphoid compartments were defined as CD45-PECy7 negative and CD45-DyLight® 405 positive. Blood leukocytes were defined as single positive for CD45-PECy7, as they were exposed to the in vivo injected antibody but harvested prior to exogenous addition of CD45-DyLight® 405. Lavage leukocytes, unstained at the time of harvest, were subsequently stained with CD45-DyLight® 405.

2.3.6. Flow Cytometry and Analysis

Fluorescence intensity was measured with a Cyan ADP LX 9-color cytometer (Dako) with 405 (450/50, 530/40 emitter filters), 488 (530/40, 575/25, 613/20, 680/30, 750LP emitter filters), and 642 (665/20, 750LP emitter filters) nm excitation lasers. Collected samples were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar) to determine the relative percentage of each leukocyte subset in lung, blood, and lavage samples. The absolute number of cells in each leukocyte subset was calculated as the product of the relative percentages and the total number of cells in the sample.

2.3.7. Calculation of Cells in Blood Compartment

We defined the “blood compartment” as the total circulating volume of blood in the mouse. To estimate the number of cells in this compartment, we first determined the absolute number of each leukocyte subset present in each collected blood sample using flow cytometry. We then divided this number by the volume of blood collected for that sample, resulting in a concentration for each leukocyte subset per mL of whole blood collected. We assumed an average weight of 20 grams per mouse and an average blood volume of 5.5 mL per 100 gram body weight (The Jackson Laboratory), which allowed us to estimate the absolute number of circulating cells in the whole mouse “blood compartment.”

2.4. Evans Blue Permeability

Vascular permeability of the lungs was assessed using Evans blue dye (EBD) extravasation as previously described (Wallace et al., 2009). Briefly, anesthetized animals were injected with 30 mg/kg body weight EBD in 200 μL sterile saline via retro-orbital injection. EBD was allowed to circulate for 30 minutes, and then the chest was opened and the lungs were flushed with 10 mL PBS via right ventricle puncture to remove any excess dye from the pulmonary vasculature. Lungs were weighed, homogenized in 1 mL formamide, and then incubated overnight at 37°C to extract the EBD. A spectrophotometer was used to measure both the optical density (E) of EBD and that of contaminating heme pigments. The final EBD concentration was determined using the formula E620(corrected) = E620 − (1.426 × E740 + 0.03) and was expressed as μg EBD per gram lung.

2.5. Histology

Lungs were harvested and processed for immunohistochemistry as described previously (Wang et al., 2001; Wallace et al., 2009). For histology of lungs following acid injury, paraffin sections (5 μm) were stained with rat anti-mouse neutrophil antibodies (anti-7/4, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) with DAB chromogen. For in vivo staining of lung leukocytes, 10 μg unlabeled rat anti-mouse CD45 primary antibody (clone M1/9.3.4.HL.2) was intravenously injected and allowed to circulate for 5 minutes prior to sacrifice. Paraffin sections were subsequently double-stained for in vivo injected anti-CD45 antibodies and endothelial cells (anti-PECAM-1, clone M-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using the ABC Kit with DAB (CD45) and VIP (CD31) chromogens. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM with n = 6 animals per group. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Students T-test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were used to compare groups, depending on data sets analyzed. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were used to compare changes in cell types over time. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results/Discussion

3.1. Validation of Compartment Assay in the Lung

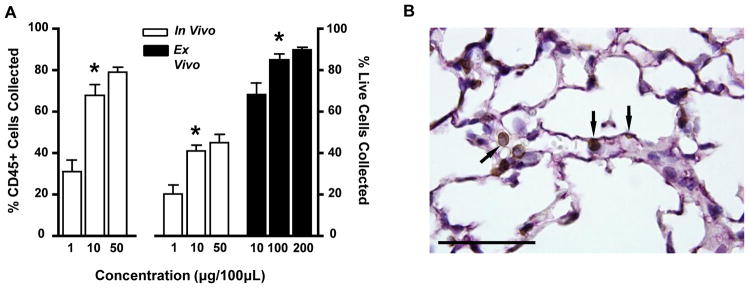

We first optimized the concentrations of in vivo injected CD45-PECy7 and ex vivo added CD45-DyLight® 405 antibodies to label all CD45+ leukocytes in the vascular compartment and whole lung, respectively (Figure 3). Initially, we followed the standard leukocyte compartment assay protocol (described in Section 2.3) but used three different concentrations of intravenous anti-CD45-PECy7 antibody. Analysis by one-way ANOVA determined the number of CD45-PECy7+ cells was significantly higher at concentrations of 10 and 50 μg/100 μL than at 1 μg/100 μL (P < 0.001); however, increasing the concentration of injected antibody above 10 μg/100 μL did not significantly change the number of labeled cells. This indicated that 10 μg of CD45-PECy7 was sufficient to label almost all leukocytes in the vascular compartment.

Fig 3.

In vivo labeling of CD45+ leukocytes. (A) Optimization of in vivo injected and ex vivo added anti-CD45 antibody concentrations by flow cytometry. The percentage of all CD45+ cells (left axis) and all live cells (right axis) labeled with either in vivo injected CD45-PECy7 or ex vivo added CD45-DyLight 405 was measured as a function of antibody concentration. (B) Confirmation of in vivo labeling of leukocytes with immunohistochemistry. Representative image of pulmonary tissue stained with in vivo injected anti-CD45 antibody (brown), anti-PECAM antibody (purple) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Scale bar represents 50μm. Arrows indicate marginated vascular CD45+ leukocytes.

A similar experiment was performed to determine the optimal concentration of the ex vivo added CD45-DyLight® 405 antibody needed to label all lung leukocytes. Mice were injected intravenously with 10 μg CD45-PECy7, then divided into three groups receiving either 10, 100, or 200 μg of ex vivo added CD45-DyLight® 405 antibody. Analysis by one-way ANOVA demonstrated that the 100 and 200 μg/100 μL concentrations labeled significantly more cells than the 10 μg/100 μL concentration (P < 0.05). There was no significant change in live cell labeling when the concentration was increased from 100 to 200 μg/100 μL. We therefore concluded 100 μg of ex vivo added CD45-DyLight® 405 was sufficient to label almost all pulmonary leukocytes.

We also used immunohistochemistry to confirm in vivo labeling of pulmonary leukocytes. An unlabeled anti-CD45 antibody was intravenously injected and allowed to circulate for 5 minutes prior to sacrifice of mice, similar to the compartment protocol for flow cytometric analysis. Subsequent staining of tissue sections revealed the in vivo injected antibody labeled intravascular pulmonary leukocytes (Figure 3B).

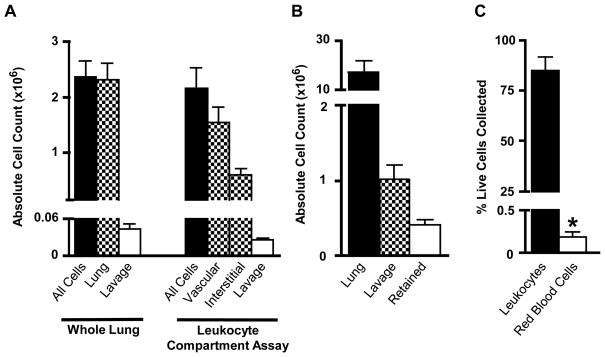

As mentioned in Section 1, we specifically chose two anti-CD45 antibodies for this assay that targeted different epitopes on the CD45 antigen in order to allow non-competitive double labeling of the leukocytes with different fluorophores. As discussed in Section 2.3.5, double-labeling distinguishes between CD45+ cells in the marginated vascular compartment, and non-vascular cells, including interstitial and alveolar leukocytes. Vascular cells were exposed first to the in vivo injected CD45-PECy7 antibody, and then to the ex vivo CD45-DyLight® 405 antibody. If the second, ex vivo antibody were unable to bind to CD45 molecules on marginated leukocytes due to competition with the bound CD45-PECy7 antibody, those cells would remain single-positive for CD45-PECy7 and would not be characterized as marginated by the assay. Thus the total number of marginated cells in the vascular compartment would be underestimated. In order to validate the procedure, we compared the total number of leukocytes (lung and alveolar lavage) collected by traditional, whole-lung flow cytometry to the sum of the number of vascular, interstitial, and alveolar lavage cells collected by the leukocyte compartment assay (Figure 4A). We found no significant difference (P = 0.68) between the absolute number of leukocytes collected by traditional, whole-lung flow cytometry (2.16 × 106 ± 3.68 × 105) and the absolute number of leukocytes collected by the compartment assay (2.35 × 106 ± 2.91 × 105). This suggests that the leukocyte compartment assay effectively labels all CD45+ cells in the lung, and that leukocytes in the vascular compartment are effectively double-labeled.

Fig 4.

Validation of the compartment assay in the lung. (A) The leukocyte compartment assay labels all CD45+ pulmonary cells. The total number of CD45+ cells labeled by the leukocyte compartment assay (vascular + interstitial + alveolar lavage) was compared to the total number of CD45+ cells harvested by standard methods (whole lung + alveolar lavage). (B) The number of alveolar cells remaining in the lung after bronchoalveolar lavage was measured and compared to the total number of CD45+ leukocytes in the lung and alveolar lavage. (C) The number of red blood cells (RBC) remaining in the lung after pulmonary vascular flush was measured as a percentage of the total number of live cells collected from the whole-lung homogenate, and compared to the total number of collected CD45+ leukocytes. Red cells were detected by anti-Ter119 antibody staining.

Another area of potential concern was the efficiency of leukocyte removal by bronchoalveolar lavage; specifically, we wanted to determine the number of alveolar cells retained in the lung after lavage was performed. These retained alveolar cells would be labeled with the ex vivo antibody during tissue mincing and subsequently incorrectly classified as interstitial. This would lead to an overestimation of the number of cells in the interstitial compartment and an underestimation of the total number of cells in the lavage. In order to quantify the number of alveolar cells remaining in the lung after lavage, we added 200 μg anti-CD45 FITC to 1 mL PBS with 5 mM EDTA and then instilled this fluid into the alveolar air space using a tracheal cannula. We allowed the fluid to remain in the lung for 5 minutes. We then washed the airway using 4 × 1 mL PBS with 5 mM EDTA, similar to a standard bronchoalveolar lavage. The resultant 5 mL of lavage fluid (1 mL CD45-FITC PBS-EDTA with 4 mL PBS-EDTA) was stained and analyzed for flow cytometry. We then harvested the pulmonary tissue and processed for flow cytometry, staining with anti-CD45 DyLight® 405. Again, we used two antibodies targeted against different epitopes of the CD45 molecule to allow double-staining of CD45+ leukocytes. Approximately 1.01 × 106 ± 1.92 ×105 CD45-FITC positive cells were collected from the alveolar lavage (Figure 4B); analysis of the whole-lung homogenate revealed 3.97 × 105 ± 7.04 × 104 CD45-FITC positive cells were retained in the alveolar space after lavage, or 18.7 percent of the total lung leukocytes. This suggests the leukocyte compartment assay may overestimate the number of cells in the interstitial compartment by as much as 18.7 percent. It is notable that this technique could be used in future to specifically to investigate the properties of tightly adhered leukocytes in the alveolar space that are resistant to removal by BAL.

Similarly, we wanted to ensure an accurate count of the marginated vascular compartment of the lung. Incomplete perfusion of the lung after in vivo injection of CD45-PECy7 antibody would allow circulating, non-marginated leukocytes to remain in the lung vascular space and be subsequently counted as marginated. This would lead to an overestimation of the number of marginated cells. To evaluate this, we measured the number of red blood cells retained in the lung after perfusion (Figure 4C). Red blood cells in naïve, uninjured mice are confined to the pulmonary vascular space; areas of poor perfusion would not only retain leukocytes but would also retain red blood cells. We performed the leukocyte compartment assay and processed the tissue for flow cytometry, omitting the red blood cell lysis step. We then stained the whole lung for the red blood cell marker Ter119. We found that only 0.2 ± 0.02 percent of all live cells harvested from the lung stained positively for Ter119, suggesting the pulmonary perfusion step is highly effective at removing almost all non-adhered blood cells. Thus cells characterized as marginated leukocytes in the compartment assay are truly marginated to the vascular wall and not simply non-adhered cells retained in the pulmonary vascular space.

3.2. Intact Tissue Architecture following Acid Injury

We next demonstrated the utility of the leukocyte compartment assay in the setting of pulmonary injury. The inflammatory reaction to injury often involves a reduction in endothelial cell barrier function and a resultant increase in vascular permeability. The leukocyte compartment assay fundamentally depends on an intact pulmonary vascular barrier; if the integrity of the vascular wall is compromised, then the intravenous injected antibody could gain access to the interstitial space. As a result, interstitial leukocytes would be labeled with CD45-PECy7 and incorrectly characterized as marginated by this assay; the ability of the leukocyte compartment assay to differentiate between vascular and interstitial cells would be lost. We therefore used the EBD assay of vascular permeability to establish a window for acceptable application of the leukocyte compartment assay.

EBD binds to blood albumin and is commonly used as a marker of vascular endothelium permeability. As the vascular endothelium becomes more permeable (i.e., during pulmonary injury), more albumin can leak across the endothelium into the interstitial space. Since the molecular weight of albumin is considerably less than that of an IgG antibody (65 kDa versus 150 kDa, respectively), a lack of permeability to albumin would suggest a similar lack of permeability to the larger in vivo injected antibody. Thus the compartment assay can be considered valid when the permeability of the pulmonary vasculature, as measured 5 minutes after injection of EBD, is not appreciably elevated compared to uninjured mice.

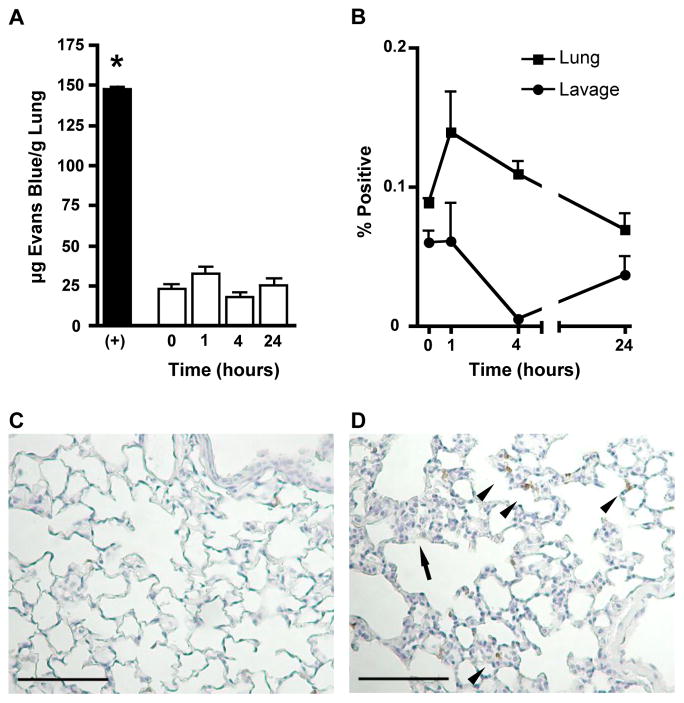

We assessed the degree of vascular permeability in uninjured (0 hour) mice as well as 1, 4, and 24 hours after administration of 0.1 N HCl (Figure 5A). In addition, we compared the degree of acid-induced pulmonary vascular leak to an established model of pulmonary inflammation with edema: NY1DD sickle cell disease mice (Wallace et al., 2009). These mice have significantly increased vascular permeability at baseline as determined by EBD (Wallace et al., 2009).

Fig 5.

Integrity of barriers between lung compartments after acid injury. (A) Pulmonary Evans Blue dye extravasation. The pulmonary vascular permeability was assessed in naïve mice (0) and 1, 4, and 24 hours after inhalation of 40 μl of 0.1 N HCl. Positive control (+) represents EBD extravasation in sickle cell diseased mice (NY1DD). (B) Percent of collected alveolar macrophages (CD11b− CD11c+ Autofluorescent+ MHCII+) in bronchoalveolar lavage and whole lung homogenate labeled with the in vivo injected CD45-PECy7 antibody. (C & D) Representative images of pulmonary tissue stained with hematoxylin (blue) and anti-7/4 neutrophil antibody (brown). Scale bars represent 100μm. Increased interstitial cellularity (arrow) and neutrophil infiltration (arrow head) as marked. Lungs harvested from (B) naïve and (C) 4 hours post-acid inhalation mice.

As expected, NY1DD mice demonstrated a significantly higher amount of pulmonary vascular leak when compared to naïve (0 hour) C57BL/6 congenic controls. Additionally, vascular leak in naïve NY1DD animals was significantly greater than in acid-injured C57BL/6 mice (P < 0.0001). Finally, the amount of vascular leak at each time point after acid injury (1, 4, and 24 hours) did not change significantly, and was not significantly different from the amount of leak in naïve (0 hour) C57BL/6 controls.

We also wanted to ensure that small amounts of unbound anti-CD45 PECy7 did not escape vascular flushing and bind to non-vascular single cell suspensions. As a control, we examined the in vivo antibody staining pattern of alveolar macrophages as characterized by the leukocyte compartment assay. Alveolar macrophages are exclusively found in the alveolar air space and not in the vascular compartment. Hence, the absence of alveolar macrophages labeled by the injected antibody can be used as evidence of the integrity of the lung barriers and failure of residual injected antibody to bind extravascular cells. Our compartment method obtains alveolar macrophages through lavage prior to lung digest. However, as demonstrated in Figure 4B, approximately 18% of alveolar macrophages are retained in the lung after lavage. We therefore determined the percent of both lavage and retained (lung) alveolar macrophages labeled by the IV injected antibody at baseline, and 1, 4, and 24 hours post-acid injury (Figure 5B). Our data suggest less than 0.2 percent of alveolar macrophages remaining in the lung are labeled with the in vivo injected antibody, confirming our hypothesis that the IV antibody remains in the vascular space during the course of acid injury, and demonstrating that residual anti-CD45 PECy7 does not label extravascular leukocytes during the lung digestion procedure.

Finally, gross comparison of lung immunohistochemistry suggests an increase in the number of recruited cells, particularly neutrophils, in acid-injured mice (Figure 5C) as compared to uninjured controls (Figure 5D). Taken together, we decided the mild acid-induced pulmonary inflammation would be a good model for testing the leukocyte compartment assay in the lung; it induces cellular recruitment to the lung but does not compromise the endothelial barrier.

3.3. Trafficking of Leukocytes Into the Lung After Pulmonary Acid Injury

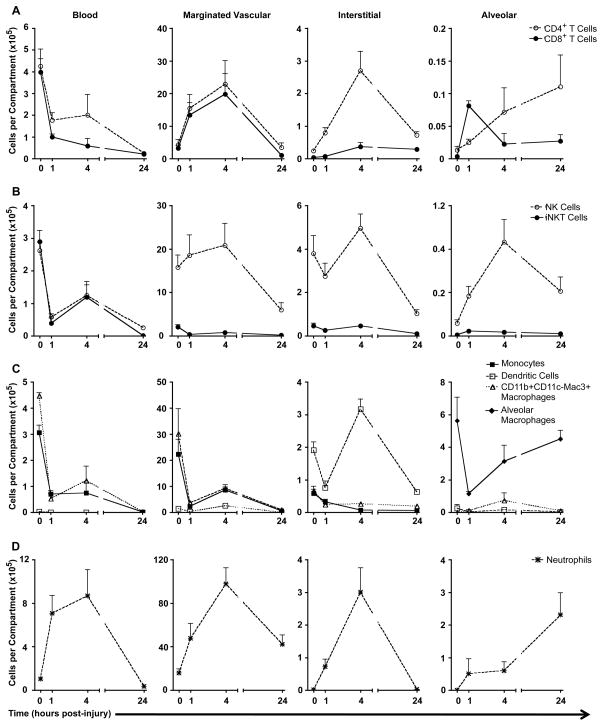

We used the leukocyte compartment assay to simultaneously monitor the trafficking of eight different subsets of leukocytes (NK cells, iNKT cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, DCs, monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages) into the lung in response to intra-tracheal acid administration (Figure 6A–D). Data were collected from uninjured mice (0 hour), and at 1, 4, and 24 hours after acid administration. As described previously in Section 2.3.6, we also estimated the number of leukocytes in the blood compartment.

Fig 6.

Trafficking of leukocytes between four pulmonary compartments (blood, vascular, interstitial, alveolar) after acid injury, grouped into leukocyte subsets: (A) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, (B) NK and iNKT cells, (C) mononuclear phagocytes, (D) neutrophils. Blood cell counts are estimated per total blood volume, marginated vascular and interstitial counts are per whole-lung homogenate, and alveolar counts are per 5 mL alveolar lavage fluid.

We hypothesized the lung would respond to acid injury by recruiting inflammatory cells, a process we could study by using the compartment assay. We also expected to observe primarily neutrophil recruitment into the pulmonary interstitial and alveolar spaces, as described previously in the acid injury literature (Reutershan et al., 2005). However, we were surprised to find large populations of several distinct leukocyte subsets residing in the naïve lung, primarily marginated to the vascular wall. Furthermore, the composition of this vascular compartment changed over time in response to injury. We also observed dynamic trafficking of cells not typically associated with acid injury (e.g., NK cells and CD4+ T cells) traffic into the interstitial and alveolar spaces in response to acid injury.

Of 11 million leukocytes found in uninjured lungs, approximately 9.5 million leukocytes were marginated to the vascular wall (Figure 6A–D, middle left panels). This was confirmed in part by histological data (Figure 3B). Double staining of sections with an in vivo-injected anti-CD45 antibody and an endothelial cell marker (PECAM) demonstrated numerous leukocytes in the pulmonary vascular space. The vascular space had been flushed with saline during processing for histology; therefore these leukocytes are likely marginated to the vascular wall. Of these, approximately 17% were NK cells, 17% neutrophils, and 54% mononuclear myeloid cells (monocytes and macrophage precursors). The remaining 12% of cells included CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, iNKT cells, and DCs. These findings are in rough agreement with reported literature describing the composition of the pulmonary vascular space (Nagase et al., 2000; Imai et al., 2005; Zarbock et al., 2006; Matute-Bello et al., 2008). The interstitial compartment of naïve mice was largely comprised of NK cells (3.79 × 105 cells or 49%) and DCs (1.91 × 105 cells or 25%) (Figure 6B–C, middle right panels). As expected, alveolar macrophages were the predominant cell type in the lavage fluid, with approximately 5.63 × 105 total cells, or 93% of lavage cells collected (Figure 6C right panel).

There were several trends apparent when looking at individual cell types over the course of acid-induced inflammation. There were similar numbers of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (4.25 × 105 and 3.97 × 105 cells, respectively) in the blood at baseline in naïve mice (Figure 6A). After acid injury, the number of T cells in the blood decreased significantly over time to 3.19 × 103 CD4+ and 2.58 × 103 CD8+ T cells at 24 hours. Concurrently, the number of T cells marginated to the lung vascular wall increased significantly from 3.75 × 105 combined CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells at baseline to an average of 1.44 × 106 T cells at 1 hour and 2.13 × 106 T cells at 4 hours post-injury (P < 0.01). The marginated T cell compartment returned to baseline at 24 hours. The number of CD4+ T cells in the interstitial compartment varied significantly over the course of injury, from approximately 2.39 × 104 cells at baseline, to a peak of 2.70 ×105 cells at 4 hours post-injury, and then returning to 7.18 × 104 cells at 24 hours after acid (P < 0.0005). There was a transient increase in the number of alveolar CD8+ T cells at 1 hour (P < 0.01), but no significant change in the number of alveolar CD4+ T cells.

The trafficking of T cells in response to acid-induced pulmonary injury has not been well described. CD4+ T cells can enhance monocyte and neutrophil effector function, and the Th1 subset of CD4+ T cells can inhibit neutrophil apoptosis (Doerschuk, 2000). Thus, the rapid recruitment of CD4+ T cells to the lung interstitial space after acid injury may be important for modulating the subsequent recruitment and activation of neutrophils and macrophages.

Figure 6B examines trafficking of NK and iNKT cells in response to acid injury. Many more NK cells were found marginated to the lung vasculature than circulating in the blood. Moreover, the number of NK cells in the blood rapidly decreased from 2.62 × 105 cells in naïve mice to 5.82 × 104 cells 1 hour post-injury (P < 0.001). The number of marginated NK cells in the lung remained constant from baseline to 4 hours post-injury (approximately 8 × 106 cells), and then deceased significantly at 24 hours to 5.99 × 105 cells (P < 0.05). The number of interstitial and alveolar NK cells increased significantly at 4 hours post-injury (4.96 × 105, P < 0.05; 8.65 × 104, P < 0.01, respectively), and then decreased at 24 hours post-injury (1.04 × 105, P < 0.01; 4.13 × 104, P < 0.05, respectively).

It is striking that the number of circulating NK cells decreased by almost 80 percent within 1 hour of acid injury, followed by an increase in the number of interstitial and alveolar NK cells at 4 hours post-injury, suggesting rapid recruitment of NK cells into the lung. Previous studies have noted the presence of NK cells in the lung (Farah et al., 2001; Mikhak et al., 2009), and their accumulation in response to inflammation and injury (Basse et al., 1992). However, the dynamic trafficking of NK cells in response to innate injury such as acute acid-induced lung injury has not been previously reported.

In general, the total number of invariant NKT cells decreased over time after acid injury. However, the number of alveolar iNKT cells quadrupled briefly at 1 hour post-injury and circulating blood iNKT cells increased significantly between 1 and 4 hours post-injury (P < 0.05 for both). It is striking that circulating and vascular marginated iNKT cells markedly declined within 1 hour of acid injury but it is not clear what happens to these cells since they do not relocate in large numbers in other lung compartments. iNKT cells have been shown to play an important role in the initiation of inflammation after pulmonary injury (Gregoire et al., 2007). Activated iNKT cells down-regulate their T-cell receptor (Wallace et al., 2009) as well as NK1.1, two of the primary markers by which iNKT cells are identified by flow cytometry, but it is unlikely that this occurs within 1 hour. Another possibility is that acid injury to the lung causes iNKT cells to marginate to vessel walls or to extravasate in tissues other than lungs.

DCs also demonstrated dynamic trafficking in response to acid injury (Figure 6C). There was a significant decrease in the number of circulating DCs at 1, 4, and 24 hours post-acid injury (P < 0.001) compared to baseline in naïve mice. The number of marginated lung DCs significantly increased between 0 and 4 hours post-injury (from 1.50 × 105 to 2.55 × 105, P < 0.001), along with the number of interstitial DCs (from 1.91 × 105 to 3.17 × 105, P < 0.001). These populations significantly decreased by 24 hours post-injury (marginated 3.39 × 103 P < 0.001; interstitial 6.25 × 104 P < 0.001). The number of DCs in the alveolar air space did not change significantly at any time point after acid injury. Thus, acid injury induced a transient influx of dendritic cells into the pulmonary interstitium, with maximal numbers at 4 hours post-injury.

Monocytes, recruited macrophages, and alveolar macrophages play an important role in pulmonary inflammation. These cells can be identified by their differential expression of several extracellular markers; we defined monocytes as CD11b+ CD11c− CD115+, recruited macrophages as CD11b+ CD11c− Mac3+, and alveolar macrophages as CD11b− CD11c+ MHCII+ (Harada et al., 2004). Non-DC mononuclear phagocytes (monocytes and recruited macrophages) significantly decreased in number in the blood, marginated vascular, and interstitial compartments at 1 hour post acid-injury (P < 0.05), and their numbers did not subsequently change significantly. In contrast, the number of alveolar macrophages decreased significantly at 1 hour post-injury, likely due to acid-induced killing, but then began to recover at 4 and 24 hours post-injury (P < 0.01, post-test for linear trend). Monocytes and recruited macrophages may contribute to this repopulation of alveolar macrophages.

The data generally agree with the reported literature on host responses to acid-induced pulmonary injury, that is, neutrophils were heavily recruited to the lung 4 hours after injury, and accumulate in both the interstitial and alveolar spaces (Figure 6D). This is accompanied by release of neutrophils from the bone marrow (Nibbering et al., 1987; Vermaelen and Pauwels, 2004; Landsman and Jung, 2007; Landsman et al., 2007; Olszewski et al., 2007; Phadke et al., 2007). We found a statistically significant increase in the number of circulating, marginated vascular, and interstitial neutrophils at 4 hours post-injury (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively). The number of neutrophils in these three compartments also significantly decreased by 24 hours (circulating blood, P < 0.01; marginated vascular, P < 0.05; interstitial P < 0.001), suggesting a transient influx of neutrophils after injury with initiation of recovery by 24 hours. Approximately 2.31 × 105 neutrophils trafficked into the alveolar space within 24 hours of injury, a statistically significant increase over baseline (P < 0.05). A prolonged analysis could determine the fate of these alveolar neutrophils, though the cells most likely complete their effector functions and undergo apoptosis.

To further clarify the interplay between the blood compartment and the marginated vascular compartment, we decided to plot the ratio of marginated vascular leukocytes in the lung to blood leukocytes over time after acid injury. This comparison revealed differential time courses for margination among cell types (Figure S1). The ratio of marginated/circulating CD8+ T cells increased significantly at 4 hours (P < 0.001), and then returned to baseline by 24 hours post-injury. In contrast, the ratio of marginated/circulating macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils continued to increase for 24 hours post injury (P < 0.01). These data suggest the marginated vascular wall is truly a distinct compartment from the pulmonary circulation or whole blood; the composition of each compartment can change rapidly over time in response to injury.

The dynamic margination observed in the setting of acid injury supports previous work on the important role of marginated cells in immune surveillance (von Vietinghoff and Ley, 2008). Marginated cells may have access to antigen presenting cells in the interstitium. This crosstalk could direct the selective recruitment of marginated leukocyte subsets to the site of tissue injury in the interstitium or alveolar space. In acid injury, there is selective recruitment of neutrophils and mononuclear myeloid cells. In the setting of viral infection, marginated crosstalk could dictate the selective response of NK and CD8+ T cells. This assay can be applied to define and describe crosstalk and activation of cells in the marginated compartment, allowing a better understanding of immune surveillance and initial cell recruitment events.

In addition, this assay allows further distinction between truly extravasated cells in the interstitial space and marginated cells in the vascular space. Standard analysis of lung samples with flow cytometry does not differentiate between these compartments; studies of “pulmonary” inflammatory cells include both marginated vascular and interstitial compartments. These cells can now be differentiated, classified, and examined for phenotypic differences such as expression of activation markers.

4. Conclusions

By devising a method to study compartmentation of multiple subsets of leukocytes in the lung, our assay has broad applications. Diverse cell types marginate to the vascular wall and then traffic into the lung with different kinetics, in vastly different numbers, and express variable adhesion molecules and activation markers depending on the stimulus. This new procedure can be used to measure recruited cell numbers and the kinetics of trafficking to the lung, and to discern expression of markers on individual cell types depending on their localization within the lung. For example, O Dea et al. (Kubes and Kerfoot, 2001; Hickey and Kubes, 2009) demonstrated GR-1high expression on a subset of monocytes marginated to the pulmonary vasculature in response to LPS injury. One limitation of the methodology described in the current study is the inability to distinguish between interstitial and lymphatic compartments; therefore the “interstitial” compartment should be more accurately named non-vascular and non-airspace. A second limitation occurs in the setting of severe pulmonary injury where endothelial barrier function is not sufficient to exclude antibodies for the interstitial space, even for a short time. The leukocyte compartment assay could be used to study other models of lung injury in which vascular integrity is maintained, such as asthma or pulmonary fibrosis, and may be adaptable to other organ systems. In sum, we believe this assay can be a valuable tool in describing leukocyte trafficking.

Supplementary Material

Ratio of marginated vascular cells to circulating blood cells by leukocyte subset. The number of cells marginated to the vascular wall for a specific leukocyte subset was divided by the estimated number of cells in the blood for that subset. Left panel: lymphoid subsets (NK, iNKT, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells). Right panel: myeloid subsets (monocytes, recruited macrophages, neutrophils).

Acknowledgments

K.E.B designed, performed, and analyzed all experiments and prepared the manuscript, R.E.C. and K.L.W. provided initial assistance with flow cytometry, S.I.R. processed tissue samples for immunohistochemistry, B.M. assisted with manuscript preparation and J.L provided experimental theory, design, and manuscript review. The author would like to thank the University of Virginia Flow Cytometry Core and Lymphocyte Culture Center, the NIH Tetramer Facility, and Adam Harris at TreeStar for FlowJo site license assistance. Supported by NIH P01-HL073361.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AI, acid injury; NK, natural killer; iNKT, invariant natural killer T; DC, dendritic cell; EBD, Evans blue dye. DyLight® is a trademark of Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. and its subsidiaries.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kathryn E. Barletta, Email: keb3t@virginia.edu.

Joel Linden, Email: jlinden@liai.org.

6.1. Journal References

- Basse PH, Hokland P, Gundersen HJ, Hokland M. Enumeration of organ-associated natural killer cells in mice: application of a new stereological method. APMIS. 1992;100:202–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1992.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerschuk CM. Leukocyte trafficking in alveoli and airway passages. Respir Res. 2000;1:136–40. doi: 10.1186/rr24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle NA, Bhagwan SD, Meek BB, Kutkoski GJ, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Doerschuk CM. Neutrophil margination, sequestration, and emigration in the lungs of L-selectin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:526–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI119189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah CS, Elahi S, Pang G, Gotjamanos T, Seymour GJ, Clancy RL, Ashman RB. T cells augment monocyte and neutrophil function in host resistance against oropharyngeal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6110–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6110-6118.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkina E, Thatte J, Dabak V, Williams MB, Ley K, Braciale TJ. Preferential migration of effector CD8+ T cells into the interstitium of the normal lung. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3473–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI24482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebb SA, Graham JA, Hanger CC, Godbey PS, Capen RL, Doerschuk CM, Wagner WW., Jr Sites of leukocyte sequestration in the pulmonary microcirculation. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:493–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire C, Chasson L, Luci C, Tomasello E, Geissmann F, Vivier E, Walzer T. The trafficking of natural killer cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:169–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Seino K, Wakao H, Sakata S, Ishizuka Y, Ito T, Kojo S, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M. Down-regulation of the invariant Valpha14 antigen receptor in NKT cells upon activation. Int Immunol. 2004;16:241–7. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey MJ, Kubes P. Intravascular immunity: the host-pathogen encounter in blood vessels. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:364–75. doi: 10.1038/nri2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, Yang P, Sarao R, Wada T, Leong-Poi H, Crackower MA, Fukamizu A, Hui CC, Hein L, Uhlig S, Slutsky AS, Jiang C, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TP, Johnson KJ, Kunkel RG, Ward PA, Knight PR, Finch JS. Acute acid aspiration lung injury in the rat: biphasic pathogenesis. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight PR, Druskovich G, Tait AR, Johnson KJ. The role of neutrophils, oxidants, and proteases in the pathogenesis of acid pulmonary injury. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:772–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubes P, Kerfoot SM. Leukocyte recruitment in the microcirculation: the rolling paradigm revisited. News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:76–80. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.2.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsman L, Jung S. Lung macrophages serve as obligatory intermediate between blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:3488–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsman L, Varol C, Jung S. Distinct differentiation potential of blood monocyte subsets in the lung. J Immunol. 2007;178:2000–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L379–99. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhak Z, Farsidjani A, Luster AD. Endotoxin augmented antigen-induced Th1 cell trafficking amplifies airway neutrophilic inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;182:7946–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizgerd JP, Meek BB, Kutkoski GJ, Bullard DC, Beaudet AL, Doerschuk CM. Selectins and neutrophil traffic: margination and Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced emigration in murine lungs. J Exp Med. 1996;184:639–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Uozumi N, Ishii S, Kume K, Izumi T, Ouchi Y, Shimizu T. Acute lung injury by sepsis and acid aspiration: a key role for cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:42–6. doi: 10.1038/76897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemzek JA, Abatan O, Fry C, Mattar A. Functional contribution of CXCR2 to lung injury after aspiration of acid and gastric particulates. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2010;298:L382–91. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90635.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibbering PH, Leijh PC, van Furth R. Quantitative immunocytochemical characterization of mononuclear phagocytes. II. Monocytes and tissue macrophages. Immunology. 1987;62:171–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Falkowski NR, Surana R, Sonstein J, Hartman A, Moore BB, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. Effect of laparotomy on clearance and cytokine induction in Staphylococcus aureus infected lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:921–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadke AP, Akangire G, Park SJ, Lira SA, Mehrad B. The role of CC chemokine receptor 6 in host defense in a model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1165–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-256OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutershan J, Basit A, Galkina EV, Ley K. Sequential recruitment of neutrophils into lung and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L807–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermaelen K, Pauwels R. Accurate and simple discrimination of mouse pulmonary dendritic cell and macrophage populations by flow cytometry: methodology and new insights. Cytometry A. 2004;61:170–77. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Vietinghoff S, Ley K. Homeostatic regulation of blood neutrophil counts. J Immunol. 2008;181:5183–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace KL, Marshall MA, Ramos SI, Lannigan JA, Field JJ, Strieter RM, Linden J. NKT cells mediate pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction in murine sickle cell disease through production of IFN-gamma and CXCR3 chemokines. Blood. 2009;114:667–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Ouellet N, Simard M, Fillion I, Bergeron Y, Beauchamp D, Bergeron MG. Pulmonary and systemic host response to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in normal and immunosuppressed mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5294–304. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5294-5304.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbock A, Singbartl K, Ley K. Complete reversal of acid-induced acute lung injury by blocking of platelet-neutrophil aggregation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3211–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI29499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6.2 Web References

- The Jackson Laboratory. Mouse Facts, Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) Web Site. 2011 Mar 29; World Wide Web (URL: http://www.informatics.jax.org/mgihome/other/mouse_facts1.shtml)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ratio of marginated vascular cells to circulating blood cells by leukocyte subset. The number of cells marginated to the vascular wall for a specific leukocyte subset was divided by the estimated number of cells in the blood for that subset. Left panel: lymphoid subsets (NK, iNKT, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells). Right panel: myeloid subsets (monocytes, recruited macrophages, neutrophils).