Abstract

Purpose

To determine rates and risk factors associated with severe post-operative complications following cataract surgery and whether they have been changing over the past decade.

Design

Retrospective longitudinal cohort study

Participants

221,594 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent cataract surgery during 1994–2006.

Methods

Beneficiaries were stratified into 3 cohorts, those who underwent initial cataract surgery during 1994-5, 1999–2000, or 2005-6. One year rates of post-operative severe adverse events (endophthalmitis, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, retinal detachment) were determined for each cohort. Cox regression analyses determined the hazard of developing severe adverse events for each cohort with adjustment for demographic factors, ocular and medical conditions, and surgeon case-mix.

Main Outcome Measures

Time period rates of development of severe post-operative adverse events.

Results

Among the 221,594 individuals who underwent cataract surgery, 0.5% (1,086) had at least one severe post-operative complication. After adjustment for confounders, individuals who underwent cataract surgery during 1994-5 had a 21% increased hazard of being diagnosed with a severe post-operative complication (Hazard Ratio (HR): 1.21; [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.05–1.41]) relative to individuals who underwent cataract surgery during 2005-6. Those who underwent cataract surgery during 1999–2000 had a 20% increased hazard of experiencing a severe complication (HR: 1.20 [95% CI: 1.04–1.39]) relative to the 2005-6 cohort. Risk factors associated with severe adverse events include a prior diagnosis of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (HR: 1.62 [95% CI: 1.07–2.45]) and cataract surgery combined with another intraocular surgical procedure on the same day (HR: 2.51 [95% CI: 2.07–3.04]). Individuals receiving surgery by surgeons with the case-mix least prone to developing a severe adverse event (HR: 0.52 [95% CI: 0.44–0.62]) had a 48% reduced hazard of a severe adverse event relative to recipients of cataract surgery performed by surgeons with the case-mix most prone to developing such outcomes.

Conclusion

Rates of sight-threatening adverse events following cataract surgery declined during 1994–2006. Future efforts should be directed to identifying ways to reduce severe adverse events in high-risk groups.

Introduction

Cataract surgery is the most common surgical procedure in the United States (U.S.).1–3 In 2004, 1.8 million Medicare beneficiaries underwent cataract surgery.4 With the aging of the U.S. population, these numbers are projected to increase considerably. While modern cataract surgery is considered a safe and effective procedure, it is not without risk. Although most complications caused by cataract surgery are not associated with long term visual impairment, there are several severe sight-threatening complications that can result in irreversible blindness.

A number of studies have assessed rates of severe post-operative complications such as endophthalmitis, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and retinal detachment following cataract surgery. While previous reports have studied changes in the rates of severe complications with the conversion from intracapsular (ICCE) to extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE)5–8, and ECCE to phacoemulsification,6,7,9 little is known about whether severe complication rates have changed since the mid 1990s when small incision phacoemulsification with non-sutured wounds became the standard of care in many developed countries. Such an analysis would help determine whether technological advances in the surgical equipment, instrumentation, surgical techniques, newer intraocular lenses, increased use of topical anesthesia and other innovations introduced in the last decade have improved the safety of this procedure.

This study assessed rates of severe complications among 3 cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries who underwent cataract surgery in 1994-5, 1999–2000, and 2005-6 to determine whether complication rates have declined over time. In addition, we examined relationships between the probability of experiencing a severe adverse event in the year following cataract surgery and demographic factors, comorbid ocular and nonocular conditions, prior or concomitant intraocular surgeries, and surgeon case-mix.

METHODS

Data

We used a 5% sample of Medicare claims to identify beneficiaries undergoing cataract surgery and severe complications following such surgery. The database contained detailed information including International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision10 (ICD-9CM) diagnosis codes, Current Procedural Terminology11 (CPT-4) procedure codes, provider unique physician identification numbers (UPIN), and service dates for all encounters. Claims data were merged with Medicare denominator files for information on enrollment dates in fee-for-service Medicare, death, and demographic characteristics of the beneficiaries. Data were linked by a unique identifier, allowing longitudinal, person-specific analysis from 1991–2008.

Study Population

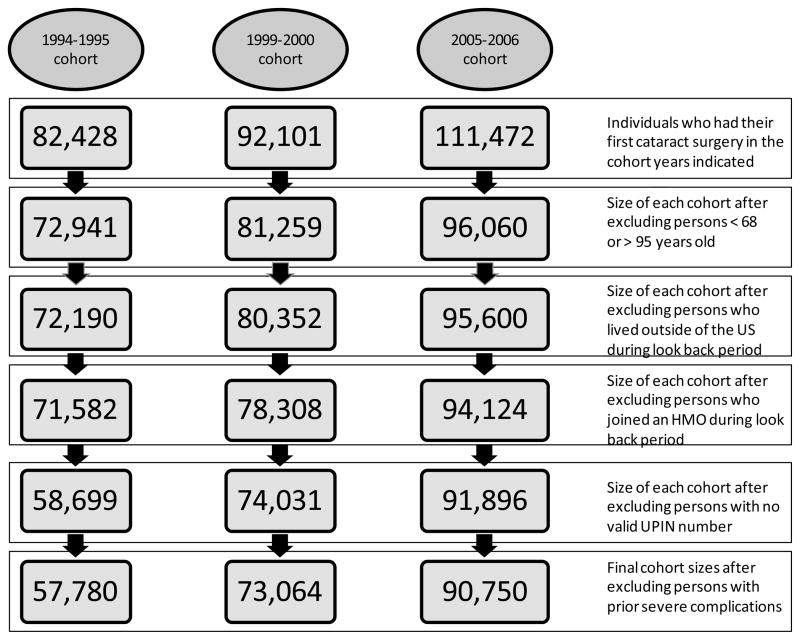

We identified all individuals receiving a first cataract surgery (CPT-4 codes: 66830–66984) during the study years and the 3 preceding years for three separate cohorts: 1994-5, 1999–2000, and 2005-6. The purpose of the 3-year look-back period was to increase the likelihood that the index procedure was the individual’s first cataract surgery. Persons with cataract surgery during the look-back period were excluded from the analysis. Persons entering Medicare risk plans (HMO) or residing outside of US for ≥12 months during the look-back period and individuals aged <68 and >95 were also excluded. We required that cataract surgeons who performed the procedure have a valid UPIN. Our final sample consisted of 57,780 Medicare beneficiaries with an index cataract surgery in 1994-5, 73,064 in 1999–2000, and 90,750 in 2005-6 (Figure 1). There were 181 (0.31%), 264 (0.36%), and 123 (0.13%) ICCE surgeries performed in the 3 respective cohorts. All of the other surgeries were coded as phacoemusification or ECCE. Since ECCE and phacoemulsification have the same ICD-9-CM billing code, we could not distinguish one from the other in the database.

Figure 1.

Attrition by Cohort

HMO = Health Maintenance Organization; US= United States; UPIN = Unique Physician Identification number

We followed individuals for 365 days following the date of the index cataract surgery or until censoring, whichever occurred first. Censoring occurred when an individual left fee-for-service Medicare and joined an HMO, resided outside the US for ≥1 year, died, or had another intraocular surgical procedure. Censoring on receipt of another intraocular surgical procedure reduced the probability of misattributing a severe complication to cataract surgery.

Dependent Variable: Severe complications

Severe complications following receipt of cataract surgery were identified using ICD-9-CM codes. Such complications were endophthalmitis (ICD-9-CM code: 360.0), suprachoroidal hemorrhage (363.6x, 363.72), rhegmatogenous (361.0), and tractional retinal detachment (361.81). The rationale for selecting these 4 conditions as “severe complications” for this analysis was to enable comparison of the findings from the current analysis with rates of previously published findings of severe complications following glaucoma surgery and pars plana vitrectomy.12,13 The only one of these 4 complications that may not be as applicable for this particular analysis was tractional retinal detachment, but this condition was extremely rare, only occurring in 0.03–0.04% of the cases for each of the 3 cohorts.

Explanatory variables

We included covariates for comorbid conditions present at the time of cataract surgery: diabetes mellitus (DM), background diabetic retinopathy (BDR), proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), age-related macular degeneration (AMD), macular hole, epiretinal membrane, ocular trauma, and less severe adverse events (choroidal effusion, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal edema, glaucoma, retinal tear, hypotony, corneal edema, or recurrent corneal erosion), prior receipt of intraocular surgery (besides retina surgery), prior receipt of retinal surgery, and Charlson comorbidity index, a widely-used general health measure.14 (Table 1, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Individuals undergoing cataract surgeries combined with other intraocular surgeries on the same day may be predisposed to developing severe complications because of the increased complexity of a combined surgery, longer procedure time, and more intraocular incisions. To account for this risk, we created a covariate for individuals undergoing combined surgeries (cataract and other), and in a separate regression model, evaluated cataract surgeries combined with: pars plana vitrectomy (PPV); corneal transplantation; incisional glaucoma surgery; and other intraocular surgeries. We also created binary variables for the season (fall, winter, spring, with summer the omitted reference group) in which individuals underwent cataract surgery. Finally, we included covariates for age, male gender, black race, other race, and in a separate analysis, studied race and gender interactions.

Although ICD codes provide detailed information on diagnoses, they lack or provide insufficient detail on severity of diagnoses or other patient-specific problems. Patients who are particularly difficult to treat may be referred to certain ophthalmologists who are specialized in caring for such patients. Such ophthalmologists may experience higher rates of adverse outcomes just because of the types of patients in their practices. We created an explanatory variable to account for this factor. To construct this variable, we identified all beneficiaries in the 5% claims files undergoing a “first” cataract surgery (as defined above) in the years not included in the study cohorts. With a binary variable for severe complications developed within 1 year of surgery as the dependent variable, we estimated a model with all of the above covariates as explanatory variables. The parameter estimates and the mean values of the covariates for each ophthalmologist in the sample were used to predict the probability of a severe complication occurring on an ophthalmologist-specific basis. The key assumption underlying this analysis was that an ophthalmologist who, at the practice level, operated on patients who were at higher risk of severe complications on observed characteristics were also at higher risk of severe complications on characteristics not reflected in the data.

After we obtained predicted probabilities of severe complications of cataract surgery for each ophthalmologist in the sample, we ranked predicted probabilities from lowest to highest and divided the predicted probabilities into quartiles. Thus, ophthalmologists who had the highest predicted probability of severe complications of cataract surgery were placed in the first quartile and similarly in descending order for the other 3 quartiles. These “case-mix” quartile rankings were included as covariates in analysis of the hazard of experiencing a severe complication at the level of the individual beneficiary.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were summarized for the entire sample using means for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. We estimated time to a diagnosis of severe complication using a Cox proportional hazard model using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For all analyses a two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Among the 221,594 sample persons who underwent cataract surgery, 26.1% (57,780) were performed in 1994-5, 33.0% (73,064) in 1999–2000, and 41.0% (90,750) in 2005-6. The mean age of the beneficiaries receiving cataract surgery was 77.5 (± 5.9) years. Compared to the 2005-6 cohort, beneficiaries in earlier cohorts were younger (p<0.001) and more likely to be nonwhite (p<0.001). Individuals in the 1994-5 cohort underwent cataract surgery at lower rates than the 2005-6 cohort (3.1 vs. 4.0%; p<0.001), while individuals in the 1999–2000 cohort underwent cataract surgery at similar rates to the 2005–2006 cohort (4.0 vs. 4.0%; p=0.91). Ninety seven percent of the cataract surgeries (214,468) were “routine” cataract surgeries (not combined with other intraocular surgeries) and 7,126 of these cataract surgeries (3%) were combined with corneal, glaucoma, or retinal surgery on the same day.

Overall, 0.5% (1,086) of beneficiaries who underwent cataract surgery experienced at least 1 severe adverse event in the 1-year post-operative period (Table 2). Among those who experienced a severe adverse event, 0.16% (357) were diagnosed with endophthalmitis, 0.06% (123) were diagnosed with a suprachoroidal hemorrhage, 0.26% (579) were diagnosed with a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and 0.04% (83) experienced a tractional retinal detachment; 0.02% (54) had more than one type of severe adverse event following cataract surgery. The probability of a severe complication declined over time: 0.6% (360) in 1994-5; (p<0.001 compared to 2005-6 cohort); 0.5% (376) in 1999–2000 p<0.001 compared to 2005-6 cohort), and 0.4% (350) in 2005-6.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Full Sample | No complication sample | Severe complication sample | p val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (prop)a | N (prop) | N (prop) | ||

| Severe complication | 1,086 (0.005) | 0 (0.00) | 1,086 (1.00) | † |

| Endophthalmitis | 357 (0.002) | 0 (0.00) | 357 (0.33) | † |

| Suprachoroidal hemorrhage | 123 (0.001) | 0 (0.00) | 123 (0.11) | † |

| Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment | 579 (0.003) | 0 (0.00) | 579 (0.53) | † |

| Tractional retinal detachment | 83 (0.0004) | 0 (0.00) | 83 (0.08) | † |

| Multiple complications | 54 (0.0002) | 0 (0.00) | 54 (0.05) | † |

| Cohort | ||||

| 1994-5 | 57,780 (0.26) | 57,420 (0.26) | 360 (0.33) | † |

| 1999–2000 | 73,064 (0.33) | 72,688 (0.33) | 376 (0.35) | |

| 2005-6 | 90,750 (0.41) | 90,400 (0.41) | 350 (0.32) | † |

| Prior diagnosis | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 64,569 (0.29) | 64,221 (0.29) | 348 (0.32) | * |

| Background diabetic retinopathy | 10,113 (0.05) | 10,037 (0.05) | 76 (0.07) | ‡ |

| Proliferative diabetic retinopathy | 2,493 (0.01) | 2,458 (0.01) | 35 (0.03) | † |

| Age-related macular degeneration | 40,988 (0.19) | 40,777 (0.19) | 211 (0.19) | |

| Macular hole | 2,367 (0.01) | 2,333 (0.01) | 34 (0.03) | † |

| Epiretinal membrane | 5,833 (0.03) | 5,767 (0.03) | 66 (0.06) | † |

| Less severe complication | 59,401 (0.27) | 58,994 (0.27) | 407 (0.38) | † |

| Trauma | 142 (0.001) | 140 (0.001) | 2 (0.002) | |

| Intraocular procedure | 1,519 (0.007) | 1,505 (0.007) | 14 (0.01) | |

| Retina surgery | 6,522 (0.03) | 6,438 (0.03) | 84 (0.08) | † |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean) | 1.51 | 1.50 | 1.73 | † |

| Same day intraocular procedure | 8,165 (0.04) | 8,030 (0.04) | 135 (0.12) | † |

| Pars plana vitrectomy | 1,039 (0.005) | 992 (0.004) | 47 (0.04) | † |

| Cornea procedure | 466 (0.002) | 458 (0.002) | 8 (0.007) | * |

| Glaucoma procedure | 3,682 (0.02) | 3,645 (0.02) | 37 (0.03) | ‡ |

| Another intraocular procedure | 3,291 (0.02) | 3,241 (0.01) | 50 (0.05) | † |

| Probability of developing a severe complication | ||||

| Lowest quartile | 55,689 (0.25) | 55,514 (0.25) | 175 (0.16) | † |

| 2nd lowest quartile | 55,507 (0.25) | 55,276 (0.25) | 231 (0.21) | ‡ |

| 3rd lowest quartile | 55,409 (0.25) | 55,177 (0.25) | 232 (0.21) | ‡ |

| Highest quartile | 54,989 (0.25) | 54,541 (0.25) | 448 (0.41) | † |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (mean in years) | 77.54 | 77.54 | 77.85 | |

| Male | 77,967 (0.35) | 77,522 (0.35) | 445 (0.41) | † |

| White | 200,862 (0.91) | 199,884 (0.91) | 978 (0.90) | |

| Black | 13,151 (0.06) | 13,078 (0.06) | 73 (0.07) | |

| Other race | 7,581 (0.03) | 7,546 (0.03) | 35 (0.03) | |

| Observations | 221,594 | 220,508 | 1,086 | |

prop= proportion; p val – p value: compares no sample complication with severe complication.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Characteristics of Beneficiaries who Developed Severe Complications

The mean age of those beneficiaries who experienced a severe post-operative complication after cataract surgery (77.8 ± 6.4 years) was not significantly different from those who did not experience a severe complication (77.5 ± 5.9 years; p=0.12). Among those who developed a severe adverse event, 41.0% (445) were male, 90.1% (978) were white, 6.7% (73) were black, and 3.2% (35) were another race.

Nearly a third of persons in the analysis sample (29.1%, N=64,269) had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus during the look-back period, 15.7% (10,113) were diagnosed with background diabetic retinopathy (BDR) and 3.9% (2,493) were diagnosed with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). Proportions of individuals with DM, BDR, and PDR, who experienced a postoperative severe adverse event were 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.4%, respectively. Approximately 1% of sample persons (0.7%, N=1,519) had had prior intraocular surgery (aside from retina surgery), while 3% of beneficiaries (2.9%, N= 6,522) had had prior laser or incisional retinal surgery before undergoing cataract surgery.

There were 7,126 individuals (3%) who underwent cataract surgery and another intraocular surgical procedure on the same date. Among these, there were 1,039 cataract surgeries combined with pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), 466 cataract surgeries combined with corneal transplantation, 3,682 cataract surgeries combined with incisional glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy or glaucoma drainage implantation), and the remainder received another intraocular surgical procedure on the same day. Five individuals underwent cataract surgery combined with >1 of these other surgical procedures on the same day. The proportion of beneficiaries who experienced a severe complication was 4.7%, 1.7%, 1.0%, 1.5% among those who underwent combined cataract surgery with PPV, corneal transplantation, incisional glaucoma surgery, and another intraocular surgical procedure, respectively.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses

After adjustment for covariates, beneficiaries undergoing cataract surgery in 1994-5 had a 21% increased hazard of being diagnosed with a severe post-operative complication (Hazard Ratio (HR): 1.21; [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.05–1.41]) compared to 2005-6 (the omitted reference group); beneficiaries undergoing such surgery during 1999–2000 had a 20% increased hazard of experiencing a severe complication (HR: 1.20 [95% CI: 1.04–1.39]; Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard of developing a severe complication

| Main Analysis specification | Specification with race and gender interactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Adjusted HR | 95% CIs | Adjusted HR | 95% CIs |

| 1994–1995 a | 1.214 | 1.045 – 1.410 | 1.214 | 1.045 – 1.410 |

| 1999–2000 a | 1.204 | 1.040 – 1.393 | 1.203 | 1.040 – 1.393 |

| Prior diagnosis | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.005 | 0.868 – 1.164 | 1.004 | 0.867 – 1.163 |

| BDR | 1.006 | 0.750 – 1.348 | 1.005 | 0.750 – 1.347 |

| PDR | 1.620 | 1.072 – 2.447 | 1.621 | 1.073 – 2.449 |

| ARMD | 0.962 | 0.824 – 1.123 | 0.962 | 0.824 – 1.123 |

| Macular hole | 1.742 | 1.203 – 2.524 | 1.742 | 1.202 – 2.523 |

| Epiretinal membrane | 1.724 | 1.316 – 2.260 | 1.722 | 1.314 – 2.257 |

| Less severe complication | 1.204 | 1.054 – 1.375 | 1.204 | 1.054 – 1.375 |

| Ocular trauma | 1.459 | 0.363 – 5.862 | 1.46 | 0.364 – 5.866 |

| Intraocular surgical procedure | 0.883 | 0.517 – 1.506 | 0.883 | 0.518 – 1.507 |

| Retina surgery | 1.586 | 1.199 – 2.098 | 1.587 | 1.199 – 2.099 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.029 | 0.998 – 1.060 | 1.029 | 0.998 – 1.061 |

| Combined procedure | ||||

| Intraocular surgical procedure | 2.506 | 2.068 – 3.037 | 2.508 | 2.069 – 3.039 |

| Provider case–mix | ||||

| Lowest quartile | 0.528 | 0.441 – 0.632 | 0.528 | 0.441 – 0.632 |

| 2nd lowest quartile | 0.637 | 0.541 – 0.749 | 0.637 | 0.541 – 0.749 |

| 3rd lowest quartile | 0.600 | 0.511 – 0.705 | 0.600 | 0.511 – 0.705 |

| Season of the year | ||||

| Spring | 1.089 | 0.927 – 1.281 | 1.089 | 0.927 – 1.280 |

| Fall | 0.945 | 0.797 – 1.120 | 0.945 | 0.797 – 1.120 |

| Winter | 1.078 | 0.911 – 1.276 | 1.078 | 0.910 – 1.276 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 1.006 | 0.996 – 1.016 | 1.006 | 0.996 – 1.016 |

| Male | 1.232 | 1.090 – 1.392 | ||

| Black | 0.873 | 0.685 – 1.112 | ||

| Other race | 0.749 | 0.533 – 1.053 | ||

| Race-sex interactions b | ||||

| White * male | 1.249 | 1.099 – 1.420 | ||

| Black * female | 0.995 | 0.659 – 1.502 | ||

| Black * male | 0.917 | 0.683 – 1.232 | ||

| Other race * female | 0.854 | 0.502 – 1.455 | ||

| Other race * male | 0.8 | 0.517 – 1.240 | ||

Note: This table shows the hazard of developing a severe complication in the main model and in a model which also includes interactions between sex and race. The first two rows indicate the hazard of developing severe complications in each of the two earlier cohorts relative to the 2005–2006 cohort. These hazard ratios were adjusted for each of the other factors in the model including prior diagnoses, same day surgeries, provider case-mix, time of year of the surgery, and demographics, hence they reflect differences among the cohorts of the hazard of experiencing severe complications following “routine” cataract surgery

2005–2006 cohort is the reference group;

White females is the reference group

Bold type denotes p<0.05; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BDR = background diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; ARMD = macular degeneration

Males had a 23% increased hazard of experiencing a severe post-operative event (HR: 1.23 [95% CI: 1.09–1.39]) as compared to female beneficiaries. There were no significant differences in rates of severe adverse events among blacks or other races relative to whites. In the model including race and gender interactions, compared with white females, white males had a 25% increased hazard of experiencing a severe adverse event (HR: 1.25 [95% CI: 1.10–1.42]) while black males and black females did not have a significantly increased hazard of severe complications relative to white females (Table 3).

While enrollees with DM with no documented retinopathy and those with BDR did not have a significantly higher hazard of severe post-operative complications, persons with a prior diagnosis of PDR (HR 1.62 [95% CI: 1.07–2.45]) had a 62% increased hazard of developing severe adverse events. In addition, those with macular hole (HR: 1.74 [95% CI: 1.20–2.52]), epiretinal membrane (HR: 1.72 [95% CI: 1.32–2.26]), and a less severe prior adverse event (HR: 1.20 [95% CI: 1.05–1.38]) had an increased risk of being diagnosed with a severe adverse event in the year following cataract surgery. Beneficiaries with prior retinal surgery had a 59% increased hazard of experiencing a severe post-operative event (HR: 1.59 [95% CI: 1.20–2.10]) compared to individuals with no prior intraocular surgery.

Individuals who underwent cataract surgery by surgeons in the highest quartile (surgeons with the case-mix least prone to post-operative complications, (HR: 0.53; [95% CI: 0.44–0.63]), the second highest quartile (HR:0.64, [95% CI: 0.54–0.75) and the second lowest quartile (HR:0.60, [95% CI: 0.51–0.71) all had significantly decreased hazards of being diagnosed with a severe adverse event relative to those whose surgery was performed by surgeons in the lowest quartile (those with the case-mix most prone to such outcomes). There were no statistically significant differences between individuals in any of the three quartiles of better case-mix.

In the main analysis, persons undergoing another intraocular procedure on the same day as cataract surgery were more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with a severe postoperative event (HR: 2.51 [95% CI: 2.07–3.04]). (Table 3) In a subanalysis investigating same-day combined cataract and other common eye surgeries, those who underwent a combined PPV with cataract surgery were at a seven fold increased hazard of being diagnosed with a severe complication (HR: 7.00 [95% CI: 5.17–9.49]) while individuals undergoing combined cataract surgery with corneal transplantation or incisional glaucoma surgery did not have statistically significantly increased rates of a severe adverse events compared to those who did not undergo a combined surgery (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazard of developing a severe complication: Cataract surgery combined with vitrectomy, corneal transplant, glaucoma surgery, and other intraocular procedures

| Cohort | Adjusted HR | 95% CIs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994–1995a | 1.230 | 1.059 – 1.429 | ||

| 1999–2000a | 1.213 | 1.048 – 1.404 | ||

| Prior diagnosis | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.997 | 0.861 – 1.155 | ||

| Background diabetic retinopathy | 0.965 | 0.720 – 1.293 | ||

| Proliferative diabetic retinopathy | 1.449 | 0.958 – 2.192 | ||

| Age-related macular degeneration | 0.945 | 0.810 – 1.104 | ||

| Macular hole | 1.654 | 1.142 – 2.395 | ||

| Epiretinal membrane | 1.608 | 1.225 – 2.111 | ||

| Less severe complication | 1.295 | 1.135 – 1.479 | ||

| Ocular trauma | 1.334 | 0.331 – 5.374 | ||

| Intraocular surgical procedure | 0.979 | 0.573 – 1.673 | ||

| Retina surgery | 1.488 | 1.124 –1.969 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity index | 1.029 | 0.998 – 1.060 | ||

| Combined intraocular surgery | ||||

| Pars plana vitrectomy | 7.002 | 5.166 – 9.490 | ||

| Cornea transplant | 1.727 | 0.855 – 3.489 | ||

| Incisional glaucoma surgery | 1.194 | 0.848 – 1.682 | ||

| Intraocular surgery (other) | 2.450 | 1.833 – 3.275 | ||

| Provider case-mix | ||||

| Lowest quartile | 0.522 | 0.436 – 0.624 | ||

| 2nd lowest quartile | 0.630 | 0.536 – 0.741 | ||

| 3rd lowest quartile | 0.599 | 0.510 – 0.704 | ||

| Season of the year | ||||

| Spring | 1.090 | 0.927 – 1.282 | ||

| Fall | 0.945 | 0.797 – 1.120 | ||

| Winter | 1.079 | 0.911 – 1.277 | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 1.006 | 0.996 – 1.017 | ||

| Male | 1.238 | 1.096 – 1.399 | ||

| Black | 0.887 | 0.696 – 1.130 | ||

| Other race | 0.757 | 0.538 – 1.063 | ||

2005–2006 cohort is the reference group. Bold type denotes p<0.05

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval

Note: This table shows the hazard of developing a severe complication among the 3 cohorts for “routine” cataract surgery and for more complex, combined same-day surgeries, adjusting for other factors in the model. The first two rows reflect differences among the cohorts of the hazard of experiencing severe complications following “routine” cataract surgery, after adjustment for the more complex surgeries. Under “Combined intraocular surgery” are the hazards of developing severe complications for combined cataract surgery with pars plana vitrectomy, corneal transplantation, incisional glaucoma surgery, and other same-day intraocular surgeries.

In a separate analysis assessing one of the severe complications, endophthalmitis, alone (results not shown), individuals in the 1999–2000 cohort were at a 46% increased risk of developing a severe complication (HR: 1.46 [95% CI: 1.14–1.87]) compared with the 2005-6 cohort while the probability of complications was not statistically different for the 1994-5 relative to the 2005-6 cohort. Endophthalmitis rates were low in all cohorts (0.16%).

DISCUSSION

Rates of severe adverse events including endophthalmitis, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and retinal detachment following cataract surgeries declined during 1994–2006. Individuals who underwent combined cataract surgery along with another intraocular surgery were at a substantially increased hazard of experiencing severe complications relative to those who underwent cataract surgery alone. While we did not find individuals diagnosed with DM and no documented retinopathy or those with BDR to have higher rates of severe post-operative events, individuals diagnosed with PDR had significantly higher rates of severe post-operative events. We found no significantly increased hazard of severe adverse events among blacks or other races relative to whites. Instead, we found white males had an increased hazard of a severe post-operative complication, compared to white females. Beneficiaries who underwent cataract surgery from a surgeon in the quartile with the case-mix most prone to developing a severe complication had considerably higher odds of developing a severe adverse event relative to those undergoing surgery from a surgeon with case-mix less prone to such adverse outcomes.

Other studies have found reduced rates of severe adverse events with the transition from ICCE to ECCE and ECCE to phacoemulsification.5–9, 15–17 However, there is some debate as to if and when rates of severe adverse events with phacoemulsification began to decline.15–17 While some studies found that rates of severe complications remained constant or possibly rose from the early 1990s to the early 2000s16–17, another study demonstrated that rates during the same time period decreased by as much as 6%.15 Our study found that compared to individuals undergoing cataract procedures in 1994-5 and 1999–2000, those undergoing cataract surgery in 2005-6 were at a reduced risk of developing severe post-operative complications. The reduction in severe complications over time following cataract surgery observed in our study may be attributed to technological innovations in phacoemulsification machines, types of instruments available to the surgeon to better manage complex cases (pupil stretchers; capsular tension rings; dyes to stain the capsule), an increase in topical anesthesia use, improvements in intraocular lenses, changes in pre- or postoperative medication regimens, and better strategies for dealing with intraoperative complications.

Given the concern about whether the increased use of sutureless clear corneal incisions since the late 1990s has resulted in higher rates of endophthalmitis17, the findings from the present analysis are reassuring. While others have found that rates of post-operative complications may have initially increased using this technique16–17, we found that by the mid 2000s, rates of endophthalmitis and other complications had decreased substantially.

Possible reasons for the increased risk of complications for beneficiaries undergoing cataract surgery combined with other intraocular surgery include a longer amount of time in the operating room, exposure to additional instruments and more incisions into the eye, all of which can increase the risk of complications such as endophthalmitis. Furthermore, use of retrobulbar anesthesia, the additional manipulation of ocular tissues, and fluctuations in intraocular pressure during these combined cases may predispose patients to suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Assessing cataract surgery combined with corneal transplantation, incisional glaucoma surgery, and PPV separately, individuals who underwent combined cataract surgery with PPV were at considerably higher risk of developing severe complications. Unfortunately, with claims data alone we cannot deduce the clinical circumstances surrounding these combined surgeries. Thus, we have no way of knowing whether the combined procedure was pre-planned, as is often the case, or whether it was undertaken due to an intraoperative complication, such as a dropped nuclear fragment during cataract surgery which necessitated the PPV. Occasionally it is necessary to perform combined surgery (for example, a non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage that is difficult to safely remove because of the coexistence of a dense cataract). However, on other occasions, the decision of whether to address both the cataract and the other condition depends on surgeon and patient preferences, weighing the risks and benefits of combined surgery versus addressing each condition sequentially. Additional research is needed to determine whether or not it is safer to perform sequential surgery instead of combined surgery when both are options.

Others have documented higher rates of cataract surgery complications among individuals with diabetes, especially those with more advanced retinopathy.18–20 Here we find no difference in severe complication rates for those with DM with no documented retinopathy or those with BDR, while our findings on PDR are consistent with past work. Given these findings, as others have suggested, offering patients with DM cataract surgery earlier, before their retinopathy progresses to PDR, might be beneficial.19

Prior studies have reported racial disparities in rates of adverse events such as endophthalmitis following cataract surgery16, which were not supported by our study. Other studies, as did we, have shown higher rates of complications in males.18,21 Possible explanations for this include behavioral differences (differences in adherence to post-operative instructions and antibiotic regimens) among males versus females,22 differences in eyelid margin bacterial flora between sexes,23 and possibly greater complexity of cataract surgery in some male patients from alpha antagonist use which can predispose patients to complications resulting from intraoperative floppy iris syndrome.24

A frequent criticism of report cards of adverse outcome rates for physicians’ practices and hospitals is that case-mix varies in ways that cannot fully be accounted for. Our empirical results support this contention, which serves as a reminder of the importance of risk adjustment in comparing outcomes of providers.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size, which enabled us to study uncommon adverse events such as endophthalmitis and suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Furthermore, unlike other studies that have assessed complication rates for a single surgeon or at a specific academic medical center that may reflect a particular case-mix or selection bias, e.g., in being exceptional and thus willing to share its data with others, this study captured rates of complications among Medicare beneficiaries throughout the U.S.

We acknowledge the following limitations. The data for this analysis were from Medicare claims, which were developed for billing purposes. Based on claims records alone, some patients may have been misdiagnosed or misclassified. Without access to the actual medical records it is impossible to verify the presence or absence of complications. Furthermore, this database does not have information on clinical parameters such as visual acuity or measures of health-related quality of life to enable us to assess the impact of the severe adverse events captured in this analysis on visual or functional outcomes. Additional studies are needed to assess whether our study findings can be generalized to other groups of patients such as those in the Veterans Administration system, patients younger than 68, uninsured or underinsured patients, and those undergoing cataract surgery in other countries. Because of Medicare data use restrictions, we were limited in determining the effects that individual surgeon or surgical center characteristics may have played. Finally, the focus of this study was on severe, potentially sight-threatening postoperative complications. There are certainly many other postoperative complications associated with cataract surgery, such as posterior capsule rupture, vitreous loss, corneal endothelial cell loss, and iris trauma. Unfortunately, there are no ICD-9-CM billing codes that adequately identify the presence or absence of these less serious complications.

In sum, individuals undergoing cataract surgery in 2005-6 received fewer diagnoses of severe post-operative adverse events compared to persons undergoing cataract surgery in 1994-5 and 1999–2000. We also identified several risk factors associated with potentially sight-threatening severe post-operative complications following cataract surgery.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

List of Diagnosis and Procedure Codes

| Cataract extraction | 66830–66984 |

| Severe complications | |

| Endophthalmitis | 360.0x |

| Suprachoroidal hemorrhage | 363.6x, 363.72 |

| Tractional retinal detachment | 361.81 |

| Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment | 361.0, 361.0x |

| Retina surgery | |

| Vitrectomy | 65260, 65265, 66850, 66990, 67036, 67038, 67039, 67040, 67108, 67299 |

| Repair retinal detachment | 67101, 67105, 67107, 67110, 67112, 67115, 67120 |

| Vitreous Tap | 67015 |

| Intravitreal Injection | 67028 |

| Laser retinopexy | 67141, 67145 |

| Panretinal photocoagulation | 67228 |

| Focal laser | 67210 |

| Intraocular surgery* | |

| Enucleation/evisceration | 65091, 65093, 65101, 65103, 65105 |

| Ruptured globe repair | 65270–65290 |

| Keratoplasty | 65710–65755 |

| Keratoprostesis | 65770 |

| Corneal surgery to correct surgically induced astigmatism | 65772–65775 |

| Paracentesis of anterior chamber with removal vitreous, blood, etc. | 65800–65805, 65810, 65815 |

| Synechialysis (not including goniosynechialysis) | 65870, 65875, 65880 |

| Removal of epithelial downgrowth, implanted material, blood clot | 65900, 65920, 65930 |

| Injection of air, liquid, or medications into anterior chamber | 66020, 66030 |

| Trabeculectomy | 66150, 66155, 66160, 66165 |

| Incisional glaucoma surgery | 66170, 66172, 66180 |

| Wound revision major/minor | 66250 |

| Surgical peripheral iridotomy (PI) | 66500–66505 |

| Repair iris | 66680, 66682 |

| Intraocular lens (IOL) repositioning | 66825 |

| Insertion of IOL (not associated with cataract surgery) | 66985 |

| IOL exchange | 66986 |

| Partial anterior vitrectomy | 67005, 67010 |

| Injection medication into vitreous | 67025, 67027 |

| Co-morbid conditions | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250.xx |

| Background diabetic retinopathy | 362.01 |

| Proliferative diabetic retinopathy | 362.02 |

| Age-related macular degeneration | 362.5, 362.50, 362.51, 362.52, 362.57 |

| Macular hole | 362.54 |

| Epiretinal membrane | 362.56 |

| Trauma (ruptured globe and intraocular foreign body) | 871.0, 871.1, 871.2, 871.5, 871.6 |

| Panuveitis | 360.12 |

| Cataract | 366.x |

| Less severe complication | |

| Choroidal detachment | 363.7, 363.70, 363.71 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 362.81 |

| Retinal edema | 362.07, 362.53, 362.83 |

| Glaucoma | 365.x |

| Retinal tear | 361.30, 361.31, 361.32, 361.33 |

| Hypotony | 360.3, 360.30, 363.31, 363.32, 360.34 |

| Corneal edema | 371.20, 371.21, 371.22, 371.23 |

| Recurrent corneal abrasion/erosion | 371.42 |

Does not include retinal surgeries

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Eye Institute K23 Mentored Clinician Scientist Award (1K23EY019511-01), National Institute on Aging, 2R56AG017473, American Glaucoma Society Clinician Scientist Grant, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Table 1

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Javitt JC, Kendix M, Tielsch JM, et al. Geographic variation in utilization of cataract surgery. Med Care. 1995;33:90–105. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escarce JJ. Would eliminating differences in physician practice style reduce geographic variations in cataract surgery rates? Med Care. 1993;31:1106–18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldzweig CL, Mittman BS, Carter GM, et al. Variations in cataract extraction rates in Medicare prepaid and fee-for-service settings. JAMA. 1997;277:1765–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Ophthalmology Cataract and Anterior Segment Panel. Cataract in the Adult Eye. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2006. [Accessed on February 9, 2011]. Preferred Practice Pattern; p. 8. Available at: http://one.aao.org/CE/PracticeGuidelines/PPP.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javitt JC, Vitale S, Canner JK, et al. National outcomes of cataract extraction: endophthalmitis following inpatient surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1085–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080080045025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morlet N, Li J, Semmens J, Ng J team EPSWA. The Endophthalmitis Population Study of Western Australia (EPSWA): first report. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:574–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.5.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norregaard JC, Thoning H, Bernth-Petersen P, et al. Risk of endophthalmitis after cataract extraction: results from the International Cataract Surgery Outcomes Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:102–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wetzig PC, Thatcher DB, Christiansen JM. The intracapsular versus the extracapsular cataract technique in relationship to retinal problems. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:339–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somani S, Grinbaum A, Slomovic AR. Postoperative endophthalmitis: incidence, predisposing surgery, clinical course and outcome. Can J Ophthalmol. 1997;32:303–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Physician ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. 1 and 2. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CPT 2006. Current Procedural Terminology, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein JD, Zacks DN, Grossman D, et al. Adverse events after pars plana vitrectomy among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1656–1663. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein JD, Ruiz D, Jr, Belsky D, et al. Longitudinal rates of postoperative adverse outcomes after glaucoma surgery among Medicare beneficiaries 1994 to 2005. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman EE, Roy-Gagnon M, Fortin E, et al. Rate of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in Quebec, Canada, 1996–2005. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:230–4. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West ES, Behrens A, McDonnell PJ, et al. The incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery among the U.S. Medicare population increased between 1994 and 2001. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taban M, Behrens A, Newcomb RL, et al. Acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:613–20. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narendran N, Jaycock P, Johnston RL, et al. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55,567 operations: risk stratification for posterior capsule rupture and vitreous loss. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:31–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somaiya MD, Burns JD, Mintz R, et al. Factors affecting visual outcomes after small-incision phacoemulsification in diabetic patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:1364–71. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips WB, II, Tasman WS. Postoperative endophthalmitis in association with diabetes mellitus. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:508–18. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatch WV, Cernat G, Wong D, et al. Risk factors for acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tordoff JM, Bagge ML, Gray AR, et al. Medicine-taking practices in community-dwelling people aged > or =75 years in New Zealand. Age Ageing. 2010;39:574–80. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekibele CO, Kehinde AO, Ajayi BG. Upper lid skin bacterial count of surgical eye patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2008;37:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell CM, Hatch WV, Fischer HD, et al. Association between tamsulosin and serious ophthalmic adverse events in older men following cataract surgery. JAMA. 2009;301:1991–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.