Abstract

Vertebrate hematopoiesis is a complex developmental process that is controlled by genes in diverse pathways. To identify novel genes involved in early hematopoiesis, we conducted an ENU (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea) mutagenesis screen in zebrafish. The mummy (mmy) line was investigated because of its multiple hematopoietic defects. Homozygous mmy embryos lacked circulating blood cells types and were dead by 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf). The mmy mutants did not express myeloid markers and had significantly decreased expression of progenitor and erythroid markers in primitive hematopoiesis. Through positional cloning, we identified a truncation mutation in dhx8 in the mmy fish. dhx8 is the zebrafish ortholog of the yeast splicing factor prp22, which is a DEAH-box RNA helicase. Mmy mutants had splicing defects in many genes, including several hematopoietic genes. Mmy embryos also showed cell division defects as characterized by disorganized mitotic spindles and formation of multiple spindle poles in mitotic cells. These cell division defects were confirmed by DHX8 knockdown in HeLa cells. Together, our results confirm that dhx8 is involved in mRNA splicing and suggest that it is also important for cell division during mitosis. This is the first vertebrate model for dhx8, whose function is essential for primitive hematopoiesis in developing embryos.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is a complicated and dynamic process occurring throughout the life of an animal. During embryonic development, the initial hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are derived from the mesoderm and share a common progenitor, called the hemangioblast, with endothelial precursors (Stainier et al., 1995; Vogeli et al., 2006). There are two sequential waves of embryonic hematopoiesis in vertebrates, primitive and definitive, which produce different sets of blood cells. In zebrafish, primitive hematopoiesis takes place in two distinct anatomical regions of the lateral mesoderm. Erythrocyte precursors migrate from the posterior mesoderm as bilateral stripes and fuse towards the midline to form the intermediate cell mass (ICM), a structure that is equivalent to the mammalian yolk sac blood islands (reviewed in (Galloway and Zon, 2003)). The second site of primitive hematopoiesis is the anterior lateral or cephalic mesoderm. This region gives rise to macrophages and granulocytes and can be identified by markers such as l-plastin and pu.1 (Herbomel et al., 1999; Bennett et al., 2001; Lieschke et al., 2001; Lieschke et al., 2002). Definitive hematopoiesis in zebrafish is thought to be initiated around 36 hpf along the ventral walls of the dorsal aorta (VDA) and is marked by expression of runx1 and c-myb. Definitive hematopoiesis is responsible for establishment of self-renewable HSCs that will persist throughout the lifespan of the animal (Thompson et al., 1998; Burns et al., 2002; Kalev-Zylinska et al., 2002). This region is equivalent to mammalian aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM), the site of definitive HSCs (Medvinsky and Dzierzak, 1996; Jaffredo et al., 1998; North et al., 2002). Studies by Jin and others have shown that cells arising between the dorsal aorta and caudal vein subsequently colonize the thymus and pronephros, the sites of adult hematopoiesis in zebrafish (Murayama et al., 2006; Jin et al., 2007). Lymphoid precursors expressing rag1, rag2 and lck are found in the thymus as early as 3 days post fertilization (dpf) (Willett et al., 1999; Langenau et al., 2004).

A number of critical players regulating hematopoiesis have been identified and studied (Okuda et al., 2001; Krause, 2002; Orkin and Zon, 2008), but the list is far from complete. A forward genetic screen has the potential for identifying additional genes whose function in hematopoiesis may have gone undetected.

One important feature of the zebrafish model is that whole genome screen after ENU mutagenesis can be performed efficiently and effectively. Large-scale mutagenesis screens conducted so far have uncovered many hematopoietic mutants (Ransom et al., 1996; Weinstein et al., 1996) (reviewed by (de Jong and Zon, 2005)). However, most of them contain defects specifically in late stages of erythroid differentiation, resulting from mutations in genes involved in erythrocyte differentiation, function, or heme synthesis. Two “bloodless” mutants were found to have defects in early erythroid differentiation: vlad tepes, mutating gata1, and moonshine, mutating transcriptional intermediary factor 1gamma (TIF1γ) (Lyons et al., 2002; Ransom et al., 2004). Only one “bloodless” mutant, cloche, was found to affect earlier stages of hematopoiesis (Stainier et al., 1995; Thompson et al., 1998; Patan, 2008). The production of all hematopoietic lineages is blocked in this mutant. Cloche mutant also have defects in angiogenesis. Therefore, the cloche mutation is generally believed to affect the function of hemangioblast, the proposed common progenitors of both hematopoiesis and angiogenesis (Vogeli et al., 2006). The mutated gene in cloche is yet to be identified conclusively, even though multiple alleles exist and an acyltransferase gene, lycat, was proposed as a strong candidate (Xiong et al., 2008).

We conducted an ENU-mutagenesis screen targeting genes involved in early hematopoiesis and/or myeloid differentiation. We report here the isolation and characterization of one mutant (mmy) that has multiple defects in embryonic hematopoiesis. We have mapped and cloned the mutated gene as the zebrafish homologue of human DHX8 and yeast prp22, which encodes a protein involved in mRNA splicing (Ono et al., 1994; Ohno and Shimura, 1996; Kittler et al., 2004).

Results

The zebrafish mummy mutant is bloodless and has defects in early hematopoiesis

In order to identify novel zebrafish genes involved in early hematopoiesis and myeloid development, we screened an ENU-mutagenized collection of 24 hour-old haploid embryos by whole mount in situ hybridization with probes for cbfb and l-plastin, markers for early hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid cells, respectively (Herbomel et al., 1999; Blake et al., 2000). This led to the isolation of mutants affecting early hematopoiesis and/or myeloid differentiation. One line, here after referred to as mummy (mmy), with decreased expression of both l-pln and cbfb, was characterized more extensively.

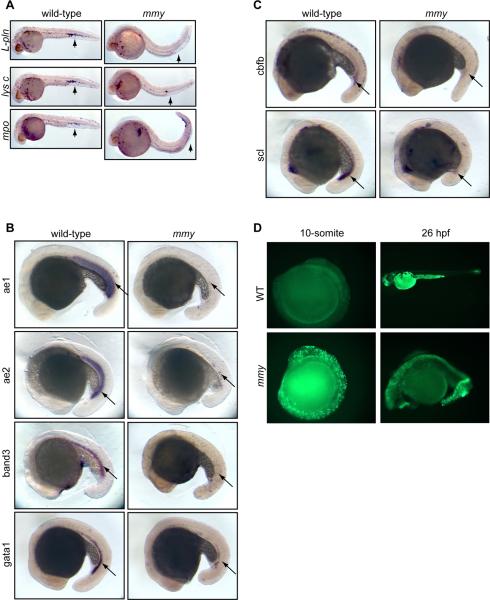

Heterozygous mmy embryos and adult fish were phenotypically normal. Homozygous mmy embryos, however, had no visible circulating blood cells. In addition to decreased expression of l-pln, mmy embryos showed decreased expression of several other myeloid specific genes including mpo, lysozyme C (Figure 1A) and c/ebpa (data not shown). To assess erythroid development, we examined the expression of aE1, aE2 globins, band3 and gata1, which are well established markers of erythroid differentiation (Lyons et al., 2002; Belele et al., 2009). Expression of aE1, aE2 globins and band3 was almost completely absent in mmy mutants while gata1 expression was significantly reduced (Figure 1B). Together, these data suggest that the gene mutated in mmy affects both myeloid and early erythroid development.

Figure 1. mmy mutants have severe defects in primitive hematopoiesis.

(A). Whole-mount in situ hybridization of myeloid markers (l-pln, lysc, and mpo) at 24 hpf. (B). Expression of erythroid markers αe1 and αe2 globins, band3 and gata1 at 21 somite. (C). Stem cell markers cbfb and scl are also down-regulated in mmy mutants. (D). Acridine orange staining showing extensive apoptosis in mmy mutants through the entire embryos. For all probes tested, we typically used 30–40 embryos per hybridization. As such, 25% (8–10embryos) will be mmy.

To further define the hematopoietic defects in mmy, we examined the expression pattern of cbfb and scl, genes expressed very early in hematopoietic differentiation. Figure 1C shows that the expression of both scl and cbfb in the ICM and posterior blood island (PBI) was significantly reduced in mmy mutants. Together, these data suggest that the mmy mutation is upstream of both scl and cbfb and may mark one of the earliest genes affecting both erythroid and myeloid specification during primitive hematopoiesis.

In addition to the above hematopoietic defects, mmy embryos were visibly deformed, exhibiting curved tails and showed obvious evidence of cell death. Acridine orange (AO) staining showed the presence of extensive cell death throughout the entire embryo, especially in the head and along the dorsal region. This was detected as early as the 10-somite stage (Figure 1D). All mmy embryos died by 30 hpf so the effect of mmy mutation on definitive hematopoiesis could not be determined.

To further characterize the developmental defects in mmy, we examined the expression pattern of the mesodermal markers flk1, ntl and myoD. No significant differences were seen between wild-type and mutant embryos for any of these markers (Figure S1A). As the kidney is the site of definitive hematopoiesis in zebrafish, we also looked at pronephric mesoderm formation as marked by the expression of paxB (pax2a). Again, no differences were seen between wild-type and mmy mutants indicating that all tissues required for hematopoiesis are present (Figure S1A). To determine if there were any defects in vascularization, mmy mutants were crossed into a fli1-GFP transgenic line (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002). As seen in the other tissue examined, fli1-GFP+ vasculature was formed in mmy mutants (Figure S2). However, since no circulating blood cells were detectable in the mmy mutant embryos, it was unclear if the vasculature was intact in the mmy mutant embryos.

As mmy embryos showed increased cell death in the brain and spinal cord (Figure 1D), we examined the expression pattern of several neuronal markers including zic (spinal cord, forebrain), krox20 (hindbrain) and paxa (spinal cord). As with the mesodermal markers, no noticeable differences were seen between wild-type and mutant embryos (Figure S1B).

Together, our in situ data showed that mmy embryos were specifically defective in the expression of hematopoietic genes and not those necessary for mesoderm or neuronal development, despite the extensive cell death.

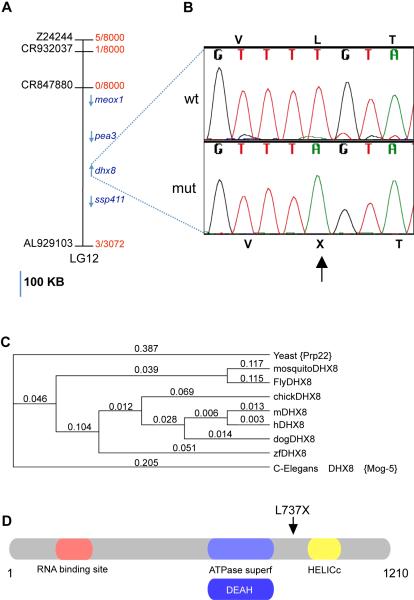

Positional cloning of mmy identifies it as the zebrafish ortholog of mammalian DHX8

Using bulked segregant analysis, the mmy candidate gene was positioned on LG (linkage group) 12 between markers z4188 (43.3cM) and z10225 (62 cM) on the MGH meiotic map panel (http://zfin.org/cgi-bin/webdriver?MIval=aacrossview.apg&OID=ZDB-REFCROSS-980521-11). For high-resolution mapping, more than 1500 mutant embryos were screened with additional markers and a candidate region of approximately 500 kb was defined by markers CR932037 and AL929103 that contained 4 known genes; meox1, pea3, dhx8 and ssp411 (Figure 2A). We sequenced the coding exons of all four genes in wild-type and the mmy embryos and identified a single ENU-induced mutation in dhx8 (Genbank Accession number XM_681116). The mutation, T2210A, changed a codon for leucine (TTG) to a stop (TAG) (L737X, Figure 2B). Over 200 wildtype zebrafish from several different strains were sequenced, none of them contained this mutation.

Figure 2. Positional cloning of mmy mutants identifies the mutated gene as the zebrafish homolog of dhx8.

(A). Physical map of the candidate region of ~ 500 kb showing the genes in the candidate region on LG12 (blue). Scale bar = 100kb. The number of recombinants over total meiosis observed is presented in red. GenBank accession numbers used to find additional di-nucleotide markers are in black. (B). DNA sequence chromatogram showing the ENU-induced mutation found in mmy. Nucleotide 2210 was mutated from a T to an A resulting in amino acid 737 changing from a leucine to a stop. (C). Phylogenetic alignment of dhx8 proteins from different species (Yeast, NP_010929, Mosquito, XP_308573, Drolophila, NP_610928, Chicken, XP_418105, Mouse, NP_659080, Human, NP_004932, Dog, XP_537627, Danio, XP_686208.1, C. Elegans, NP_495019) showing their evolutionary relations. ClustalW parameters: Open Gap Penalty = 10.0; Extended Gap Penalty = 0.1; Delay Divergent = 40%; Gap Distance =8; Similarity Matrix = blosum. (D). A schematics of dhx8 protein showing the different domains and the position of the truncation.

As the GenBank sequence of dhx8 was derived from in silico prediction, we cloned the full-length cDNA by RT-PCR from a pool of wild-type embryos at 3 dpf. The open reading frame of the cDNA encodes a predicted protein of 1210 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight of about 140 kDa. Amino acid alignment of dhx8 protein to its orthologs in other species showed that this protein is highly conserved throughout evolution from yeast to human. The zebrafish protein is 90% identical to human DHX8 (Figure 2C). Substitution of the corresponding T to A in zebrafish dhx8 produces a protein that is truncated after the DEAH box thus lacking the helicase domains (Figure 2D).

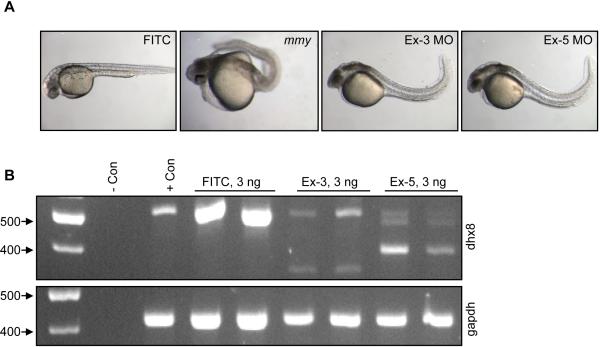

Injection of dhx8 morpholinos phenocopies the mmy phenotype

To further confirm that dhx8 is the gene responsible for the mmy phenotype, we knocked down dhx8 in wild-type embryos by morpholino (MO) injections. We designed two splice donor MOs, one to exon 3 and the other to exon 5. Injection of the exon 3 and 5 MOs at 3 ng/embryo showed a similar phenotype. By 30 hpf, many dhx8 morphants showed few to no circulating cells. The embryos showed visible signs of extensive cell death and a positive curvature of the tail was becoming prominent (Figure 3A). For exon 3 spMO, 40 of 105 (38%) of morphants showed the severe phenotype, as shown in Figure 3A, while 56 of 105 (53%) showed a milder phenotype and 9 of 105 (9%) appeared to be normal. For the exon 5 spMO, 164 of 169 (97%) showed the severe phenotype (Figure 3A) while 3% (5 of 169) displayed a milder phenotype. By 48 hpf, morphants from both splicing morpholinos showed increased cell death and displayed a more severe curvature of the tail, (data not shown). Consistent results were obtained in multiple microinjection experiments. This phenotype was not seen when a FITC control morpholino was injected at similar doses (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Knock-down of dhx8 by morpholino injections phenocopies mmy phenotype.

(A). Wild-type EK embryos were injected with 3 ng of splicing morpholinos against the donor sites in exons 3 and 5. A FITC-labeled MO was injected as a control. (B). RT-PCR analysis for dhx8 from morpholino-injected embryos in (A). Top panel shows that dhx8 is specifically knocked-down in embryos injected with either exon 3 or 5 MO resulting in aberrantly spliced products. The forward primer is located in exon1 and the reverse primer in exon 6. Bottom panel shows expression of gapdh as an internal control for RNA loading (Kohli et al., 2005).

To confirm that the phenotype of the dhx8 morphants was specifically a result of the dhx8 knock-down, we performed RT-PCR from individual injected embryos using primers starting at the ATG and ending in exon 6. Figure 3B showed that 3 ng of dhx8 MOs resulted in a drastic decrease of dhx8 full-length message and the subsequent generation of alternatively spliced products. These aberrant products were not seen in embryos injected with 3 ng of FITC control antisense MO, which targets a human β-globin intron mutation that causes beta-thalessemia. This oligo has not been reported to have other targets or generate any phenotypes in any known test system except human beta-thalessemic hematopoetic cells. (https://store.gene-tools.com/) (Thummel et al., 2008).

As a further test for the specificity of the exon 3 and 5 splicing MOs, we designed an ATG MO, which was expected to block protein translation from dhx8 mRNA. Injection of the ATG MO at 0.1 ng/nl, resulted in a pronounced phenotype; none of the injected embryos survived to gastrulation stage of development (data not shown). This result indicates the importance of this gene during early embryonic development. The phenotypic difference between embryos injected with splice donor and ATG MOs suggests the presence of maternal dhx8 transcript.

Together, these results showed that we specifically targeted dhx8 with our morpholinos and verified that the phenotype in mmy embryos resulted from dhx8 mutation. Importantly, the translational blocking ATG MO also confirms that maternal dhx8 is required for proper embryonic development.

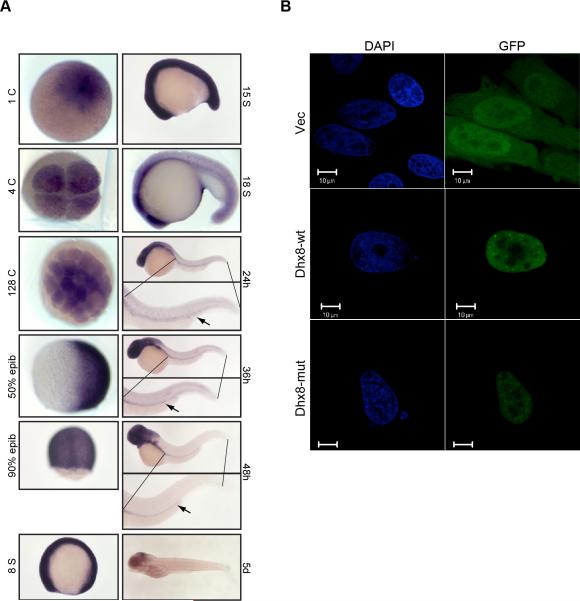

Expression and sub-cellular localization of dhx8

In order to determine the expression profile of dhx8 during embryogenesis, we conducted whole-mount in situ hybridization on wild-type embryos at multiple developmental stages. Consistent with the data from ATG MO injection, dhx8 was maternally expressed at the 1 cell stage and throughout blastula stages (Figure 4A). dhx8 expression was ubiquitous throughout the embryos until early somitogenesis, when it became restricted towards the anterior region of the embryos starting from the 18 somite stage. Dhx8 expression was completely absent from the ICM from 24 hpf onwards. From 24 hpf to 48 hpf, expression was detected mostly in the eyes and head with a faint, but detectable level in the pronephric duct. At 5 dpf, the expression was almost undetectable with only faint traces deep within the midbrain (Figure 4A). Thus, dhx8 expression is broad despite its hematopoietic phenotype.

Figure 4. Maternal and ubiquitous expression of dhx8.

(A). Whole-mount in situ hybridization of dhx8 showing that dhx8 is maternally transcribed. Expression is ubiquitous to about 15 somite stage and then gradually becomes restricted to the brain as the embryo continues to develop. At 24–48 hpf, expression can be seen in the pronephric duct, arrow. (B). dhx8 is expressed in the nucleus in a punctuate pattern. HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-dhx8 fusion constructs and observed by immunofluorescence 48 hours post transfection.

To determine the subcellular expression pattern of dhx8, HeLa cells were transfected with a GFP fusion construct expressing either wild-type or mutant dhx8. As shown in Figure 4B, over-expression of both wild-type and mutant forms of dhx8 resulted in a similarly diffused nuclear pattern. This observation was also seen with DsRed fusion constructs (data not shown). However, small nuclear speckles were seen in the wild-type transfectants but not in the mutants. The source of these speckles is unknown.

mmy embryos have defects in mRNA splicing

The yeast homolog of dhx8 is prp22. Studies in yeast have shown that prp22 facilitates nuclear export of spliced mRNA by releasing the RNA from the spliceosome complex and is involved in many aspects of mRNA processing (Tanaka and Schwer, 2005). We hypothesized that zebrafish dhx8 functions similarly, while the phenotype in the mmy embryos can be attributed to defective mRNA splicing and/or altered mRNA abundance of important genes.

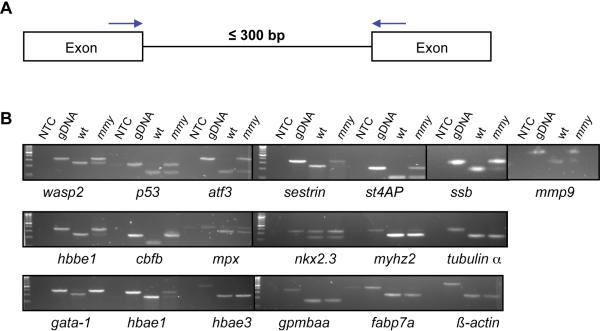

To determine if dhx8 has any role in splicing, we performed an RT-PCR assay with primers in adjacent exons (Figure 5A) from selected genes. We chose genes whose expression was dis-regulated in mmy mutants based on fold changes in a microarray analysis (Table S1) and also genes that were known to be involved in hematopoiesis (Table S2). In order to achieve consistent and efficient amplification by PCR, we further chose introns in those genes that are less than 300 bp in length (Figure 5A). As seen in Figure 5B, introns from many genes tested were not spliced completely in mmy mutants. These include wasp2, p53, atf3, 5t40ap, ssb, mmp9, hbbe1, cbfb, mpx, gata1, and hbae1. However, inefficient splicing was not detected in all of the genes tested, e.g., introns from β-actin, α-tubulin, hbae3, fabp7a and gpm6aa were all completely spliced in both wild-type and mutant embryos (Figure 5B). Notably, almost all hematopoietic genes tested showed splicing deficits and were down-regulated, suggesting a potential mechanism for the hematopoietic phenotype in the mmy embryos. Interestingly, mmp9 was up-regulated in mutant embryos and not completely spliced (Figure 5B). This suggests that mmp9 plays an important role in hematopoiesis. Indeed, a recent report has shown that mmp9 is expressed in the anterior mesoderm and can be detected in a population of circulating myeloid cells (Yoong et al., 2007).

Figure 5. mmy mutants have a defect in mRNA splicing.

(A). Schematic of the PCR assay used to assess nuclear splicing. Blue arrows indicate the locations of the forward and reverse primers. (B). RT-PCR analysis from 24 hpf wild-type and mmy mutant embryos was performed for the indicated genes (Table S5). Zebrafish genomic DNA (gDNA) was included to show the sizes of the un-spliced products. NTC: no template control.

mmy embryos have cell division defects

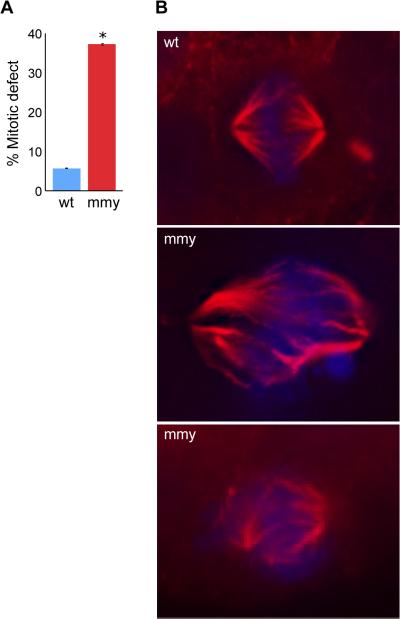

In a large-scale siRNA screen Kittler et al demonstrated that knocking down dhx8 and other RNA helicases resulted in cell division defects (Kittler et al., 2004). To assess potential cell division defects in mmy embryos, we performed immunohistochemistry on wild-type and mmy embryos using an α-tubulin antibody. These experiments showed that mmy embryos had a greater than six fold increase in the number of cells with dis-organized mitotic spindles (Figure 6A). In some cases, there appeared to be as many as three spindle poles present in one cell (Figure 6B). It is unknown whether multipolar cells are caused by a failure in centrosome duplication or a failure in chromosome condensation. DAPI (DNA) staining in Figure 6B also showed misaligned chromosomes indicating that the DNA is not aligning properly at the metaphase plate, a direct result of the spindle pole defect in these cells. These results suggest that a loss of functional dhx8 can lead to cell division defects in zebrafish embryos, which will affect cell and embryo viability.

Figure 6. mmy mutant embryos have mitotic defects.

(A) Quantification of immunohistochemistry experiment. Ten wild-type and ten mutant embryos were used to count 180 mitotic events (ME) in wild type and 221 ME in mutant embryos. The embryos were sectioned into head and trunk sections and the total number of ME for each embryo counted. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between each experiment. *: p = 0.000031 (Student's t-Test). (B) Wild-type and mutant embryos were sectioned (10 each), mounted and subjected to immunohistochemistry using an α-tubulin antibody (red) and counter stain for DNA with DAPI (blue).

Knocking down of DHX8 causes cell division defects in HeLa cells

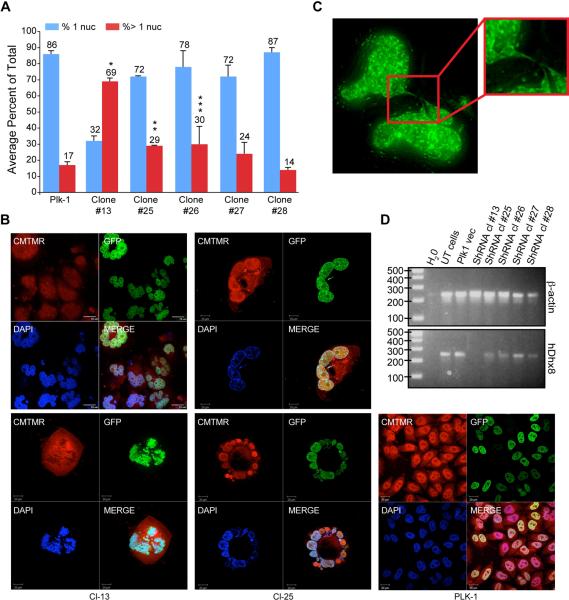

To confirm the cell division defects in mmy embryos and to demonstrate that the dhx8 mutation is responsible for these defects, we transfected H2B-GFP-HeLa cells with DHX8 shRNAs and then observed them by confocal microscopy (Figure 7A). Cells transfected with DHX8 shRNAs showed a significant increase in the number of multi-nucleated cells compared to cells transfected with empty vector. Of the five DHX8 shRNA constructs tested, #13, 25 and #26 showed the most significant effects whereas #27 and #28 had a less significant effect. Occasionally, large cells (>60μm) were seen with as many as four intact nuclei or the nuclei formed rosette structures (Figure 7B). These rosette structures were only seen in cells transfected with #13 and #25 shRNA constructs. The most effective DHX8 shRNA construct tested (#13) showed 13–25% cells with greater than four nuclei. On the other hand, only 1–2% of cells transfected with #25 contained greater than 4 nuclei.

Figure 7. Knock-down of DHX8 in HeLa cells led to mitotic defects.

(A) GFPH2B HeLa cells cultured on cover slip were transfected with 2 μg of DHX8 shRNA DNA constructs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were selected in puromycin for forty-eight hours, fixed and subjected to confocal analysis. An average from three experiments is presented. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between each experiment. P values were calculated for the % of cells with > 1 nuclei for Plk1 control vs. the different shRNA clones (Student's t-Test). *: p =0.00167, **: p =0.0149, ***: p = 0.0185. (B) Transfected cells were stained with CMTMR then subjected to confocal analysis. (C) After selection, cells were subjected to Z-sectioning. One 0.2-micron slice is shown in the GFP channel. (D) RT-PCR analysis using human specific primers for ACTIN and DHX8 after the transfected cells were selected for 2 days.

One of the most striking observations made under the confocal microscope was the presence of chromosomal bridges that connected different nuclei. They appeared as thin strings of DNA that looped in and out of different focal planes connecting different “lobes” of the nucleus (Figure 7C, Suppl. Movie 1).

To confirm that the cell division defects were in fact due to knock-down of DHX8, we performed RT-PCR analysis of HeLa cells transfected with the DHX8 shRNAs. Figure 7D showed that DHX8 shRNA #13 and# 25 resulted in the most significant reduction of DHX8 message of the five shRNAs tested, consistent with the confocal analysis (Figure 7A, B).

To further define the nature of the cell cycle defects, we performed live-cell imaging of GFP-H2B HeLa cells transfected with DHX8 shRNA #13. Two common scenarios were observed. In both cases, the DHX8 knock-down cells initiated mitosis but failed to complete it properly. In the first case, nuclear envelope breakdown and metaphase chromosome alignment appeared normal, but a thin string of DNA (chromosome bridge) connecting the two daughter cells was observed (Figure 7C). As the daughter cells moved away from each other, the chromosome bridge appeared to snap the cells back together. The plasma membranes fused, resulting in a single cell with 4N DNA and double the volume (Suppl. Movie 2). In the second scenario, mitosis resulted in an asymmetric chromosomal distribution in which both sets of chromosomes went to one of the daughter cells (Suppl. Movie 3). In both cases, the cells eventually died when they underwent another round of mitosis. These experiments suggest that DHX8 is required for mitotic exit, probably during anaphase B or telophase.

Cell death and embryonic lethality was not rescued by p53 deficiency

We hypothesize that the widespread cell death in mmy embryos (Fig 1D) was due to mitotic defects described above. However, p53 was also up-regulated (Figure S3 and Tables S1 and S2) and not completely spliced (Figure 5B) in the mmy embryos. To determine if the p53-dependent apoptotic pathway contributed to the cell death seen in mmy embryos, mmy was crossed into a p53 functional null background (Berghmans et al., 2005). However, incross between mmy+/−; p53+/- compound heterozygous did not change the expected ratio of mmy embryos indicating that loss of p53 (tp53M214K) could not rescue the apoptosis and cell death seen in mmy embryos (Table S3).

We confirmed this result by injecting mmy heterozygous incross embryos with a p53 translational blocking MO (Langheinrich et al., 2002). The p53 MO failed to rescue the mmy phenotype with injection of as much as 6 ng of the MO (Table S4). Overall the data suggest that the p53 apoptosis pathway does not contribute to the wide spread cell death seen in the mmy embryos.

Discussion

In this study we isolated the zebrafish mutant mmy as part of a forward genetic screen to identify novel genes involved in early hematopoiesis. Using polymorphic markers from the MGH panel (http://zfin.org), we were able to map and positionally clone the mutated gene as dhx8 and show its involvement in hematopoiesis and embryonic survival.

As mutation in dhx8 led to defects of both red and white blood cells, it is clear that primitive hematopoiesis are affected in mmy embryos and that dhx8 may be important at the level of the hematopoietic progenitors. Consistently, cbfb and scl, two markers for HSC, were both down-regulated in mmy embryos. On the other hand, vasculogenesis appeared to initiate normally in mmy mutants and markers for mesodermal tissues were equally expressed in wild-type and mutant embryos. The data therefore suggest that specification of the mesodermal tissue takes place correctly in the mmy mutants, and that dhx8 is indispensable for hematopoietic tissue but not for vasculogenesis. It is worth noting that from 24 hrs onwards, dhx8 was not expressed in the ICM, the site of primitive hematopoiesis (Figure 4A). Thus, we hypothesize that expression of dhx8 is required for the initiation of primitive hematopoiesis.

Based on sequence homology, dhx8 is the zebrafish ortholog of human DHX8 (Ono et al., 1994; Ohno and Shimura, 1996) and yeast prp22 (Company et al., 1991). Studies on prp22 show that it belongs to a family of ATPase helicases whose biological function and enzymatic activities are essential for life. Mutations that disrupt either the ATPase or helicase activity result in failure of the spliceosome to disassemble and lead to cell death while mutations that affect the helicase activity without affecting the ATPase activity also result in cell death (Schwer and Meszaros, 2000; Campodonico and Schwer, 2002; Schneider et al., 2002; Schneider et al., 2004). Biochemically, prp22, has been linked to many aspects of mRNA metabolism. Firstly, it promotes the second step of splicing of introns with 22bp or more between the branch point sequence and the 3' splice site (Schwer and Gross 1998). Specifically, prp22 promotes the second transesterification reaction leading to the ligation of adjacent exons and lariat formation. The main function of prp22 during this step is to release the mature mRNA from the U5 snRNP of the post-spliceosomal complex (Company et al., 1991). Secondly, Mayas et al has shown that prp22 plays an important role in suppressing splicing errors (Mayas et al., 2006). Lastly, prp22 is required for the release of mRNAs from spliceosomes. Yeast temperature sensitive prp22 mutants show an accumulation of both lariat introns and pre-RNA at the nonpermissive temperature (Company et al., 1991; Aronova et al., 2007; Schwer, 2008). As prp22 is involved in mRNA splicing, we sought to determine whether the zebrafish homolog, dhx8, also plays a role in mRNA splicing. Our RT-PCR data showed that many genes involved in hematopoiesis were unspliced in mmy mutants, including scl, mmp9, cbfb, and mpx.

Previous studies suggested that prp22/DHX8 is involved in the control of cell divisions (Kittler et al., 2004). Our results in HeLa cells confirmed the observation that loss of dhx8 in the zebrafish led to severe cell division defects. Cells treated with DHX8 shRNA were unable to complete mitosis correctly, leading to multi-nucleated cells and cell death. It is possible that DHX8 is directly required for mitotic exit, thus suggesting a new function for the gene. More likely, however, DHX8 is required to splice pre-mRNA molecules that encode proteins directly required for mitotic exit. Such preferential or selective requirement of dhx8 for the expression of certain genes has been demonstrated recently (Chen et al., 2011).

In conclusion, we reported the first vertebrate model to study the function of dhx8 in vivo. Our data show that mutations in dhx8, a ubiquitously expressed RNA helicase required for proper splicing, can lead to defects in cell division, primitive haematopoiesis and the regulation of cell death.

Materials and Methods

Fish husbandry and maintenance

Zebrafish were maintained under an approved NHGRI animal use protocol and staged as described (Kimmel et al., 1995; Westerfield and ZFIN., 2000). ENU mutagenesis was carried out in the EK Tg(Fli1;GFP) line (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002). The TL (Tubingen long tail) fish were used for map crosses. Phenylthiourea (PTU; 0.003% w/v; Sigma) was added to the water by 12 hpf to reduce melanization. EK fish were used as wild-type.

In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled antisense and sense RNA probes were synthesized as described (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002; Lyons et al., 2002). Whole-mount in situ hybridization assays were done either manually as described by Lyons et al (Lyons et al., 2002) or adapted for the fully automated InsituPro Machine (Intavis AG, Köln, Germany) with the following modification. Instead of protenase K treatment, embryos were permeabilized in RIPA buffer (0.05% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1mM EDTA, 50mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0) for 6 min. L-plastin riboprobe was made from clone BQ169336. Dhx8 riboprobes were made from CN507970, which contains the 3' end of the gene from exon 16 to the 3' UTR. Dhx8 in situ (Figure 4) was done as described by Thisse et. al (Thisse and Thisse, 2008). Typically 30–40 hybridized embryos were observed for each probe, with at least 8–10 mmy embryos among them to determine the expression pattern for each gene under study.

Sequence analysis

Primers for all candidate genes were designed by Primer3 software (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research) such that they were at least 50 bp up-stream and down-stream of the intron-exon boundaries. Sequencing reactions were carried out with Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and resolved on a 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). DNA sequences were analyzed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Cooperation, Ann Arbor, MI).

Genotyping

dhx8+/- embryos were genotyped either by using marker Z24244 that is tightly linked to the mutation or by a PCR-restriction digest-based method. A 52 bp forward primer (5'-TATGAAGCACCTATTTTTACAATCCCTGGTCGTACATACCCGGTAGAGGcTT-3') ending just before the mutation was developed. However, the 3rd to last base was mutated from an A to a C. Together with the mutated base (A) in the mmy mutant, and the G following the mutated base, a DdeI site was created (CTNAG), while this site is not present in the wild-type allele. A reverse primer (5'-TCACAAGCCGTGTCAATCTCCTCCTGACCCGTCAGGAAC-3') was designed 270 bp away. Thus, a PCR reaction would amplify from both the wild-type and mutant allele as they each contain only one bp mis-match. However, only amplification of the mutant allele will generate the DdeI site, which will result in a 220 bp fragment upon DdeI digestion, compared to the un-digested wt allele of 270 bp.

Morpholino design and injection

Anti-sense morpholinos targeting dhx8 ATG (5'-GCTCGTCTTCTCCGATCTCTGCCAT-3'), exon 3 donor site (5'-CCCAAAATGCACTTACCTTTACTGG-3'), and exon 5 splice donor site (5'-GTTAAAGCACAGATATCCTCACCTG-3') were designed and manufactured by Gene Tools (Philomath, OR). All MOs were tagged with FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate). These dhx8 morpholinos were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and the indicated amounts of the morpholinos were injected into the yolk of one-cell stage wild-type embryos. To confirm that dhx8 was specifically targeted, RT-PCR was performed on individual embryos using the SuperScript™ One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum® Taq Kit according to manufacturer's instruction (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), with an ATG forward primer (5'-ATGGCAGAGATCGGAGAAGAC-3') and an ex-6 reverse primer (5'-TGCTCCTCCGCTTCTTCCTACTG-3'). RT-PCR with gapdh primers, For (5'-ACTCCACTCATGGCCGTTAC-3') and Rev (5'-TCTTCTGTGTGGCGGTGTAG-3'), was included as a positive control for loading.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 24 hpf wild-type and mutant embryos using RNA STAT-60 (TEL-TEST, Inc. Friendswood, Tx) according to manufacturer's directions. One μg of total RNA was then subjected to RT analysis using Superscript™ III (Invitrogen). For PCR analysis, up to 200 ng of cDNA was then amplified using the appropriate primer set. The primers used to detect splicing defects in the mmy embryos are listed in Table S5. For knock-down experiments, hβ actin was amplified using primers: For 5′-GGA CTT CGA GCA AGA GAT GG, Rev 5′-AGC ACT GTG TTG GCG TAC AG and hDHX8 For 5′-CGT GCC TAC CGA GAT GAA AT, Rev 5′-ATT GGC TCC AGA GGG AAC TC.

DNA isolation and PCR

DNA, either from embryos or from fin clips, was isolated using the DNeasy cell and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's direction except that the DNA was eluted in 200 μl of EB. 5 μl of this DNA was used for PCR analysis.

Immunofluorescence

The HeLa derived cells, H2B-GFP (Dodson et al., 2007), were grown in 6-well dishes on cover slips and transfected with 2 μg each of DsRed-dhx8 fusion plasmids using lipofectamine 2000. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed 2× in 1× PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min. After fixation, cells were washed 2× for 5 min and then mounted with vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) containing DAPI and subjected to confocal microscopy.

Knockdown experiments

H2B-GFP cells were grown on cover slips in six-well dishes and transfected with 2 μg of DHX8 shRNA clones (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) using lipofectamine 2000. Thirty-six to 48 hours after transfection, cells were washed once with PBS then selected in media containing 2.5 μg/ml of puromycin for 2 days to remove untransfected cells. At that time, cells were stained with CellTracker™ Orange CMTMR according to manufacturer's directions (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, California), fixed with 4% PFA for 20 minutes then visualized using confocal microscopy. For live cell imaging, cells were transfected in 35 mm glass bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA), selected for 48 hrs in puromycin-containing media and imaged for 2–3 days using a Personal DeltaVision system (Applied Precision Inc, Issaquah, WA, USA) mounted on an inverted Olympus IX71 microscope with an oil immersion PlanApo N 60×/1.42 objective lens at 37°C with 5% CO2. All images were acquired using a CoolSNAP ES2 camera with a frame rate of 5 minutes per acquisition, 2×2 binning and a 512 pixels × 512 pixels imaging field. GFP excitation and RFP (CMTMR) excitation were collected in emission filters 457/50 and 617/40 respectively. Z-stacks were collected with a Z-interval of 0.200 microns and a total thickness of approximately 12 microns. Maximum intensity projections were created on Applied Precision's SoftWoRx software package version 4.0.0.

Immunohistochemistry

mmy and wild-type embryos were sectioned, mounted on glass slides and subjected to immunohistochemistry. The mitotic spindles of normal or mutant embryos (21s) were visualized by immunohistochemistry using α-tubulin antibody as described previously (Azuma et al., 2007). The images were taken with a PROVIS AX70 microscope (OLYMPUS).

Microarray analysis

RNA from pooled 21–26 somite wild-type and mmy mutant embryos were extracted using STAT-60 (TEL-TEST, Inc. Friendswood, Tx) according to manufacture's directions.

RNA amplification, labeling and hybridization to a 33k In-house oligo microarray chips were carried out as previously described (Pei et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2008). The hybridizations were repeated once to make sure the results were reproducible. The microarray data was analyzed via R using the marray (Gentleman et al., 2004) and limma packages (Smyth and Speed, 2003).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute and National Cancer Institute, NIH. MAE was supported by a fellowship from UNCF/Merck. We would like to thank Christine and Bernard Thisse for in situ hybridization of dhx8 during embryonic development (Thisse and Thisse, 2008), Julia Fekecs for help with graphics illustrations, and Abdel Elkahloun and Niraj S. Trivedi for performing the microarray hybridizations and analysis.

References

- Aronova A, Bacikova D, Crotti LB, Horowitz DS, Schwer B. Functional interactions between Prp8, Prp18, Slu7, and U5 snRNA during the second step of pre-mRNA splicing. Rna. 2007;13:1437–1444. doi: 10.1261/rna.572807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma M, Embree LJ, Sabaawy H, Hickstein DD. Ewing sarcoma protein ewsr1 maintains mitotic integrity and proneural cell survival in the zebrafish embryo. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belele CL, English MA, Chahal J, Burnetti A, Finckbeiner SM, Gibney G, Kirby M, Sood R, Liu PP. Differential requirement for Gata1 DNA binding and transactivation between primitive and definitive stages of hematopoiesis in zebrafish. Blood. 2009;114:5162–5172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-224709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CM, Kanki JP, Rhodes J, Liu TX, Paw BH, Kieran MW, Langenau DM, Delahaye-Brown A, Zon LI, Fleming MD, Look AT. Myelopoiesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Blood. 2001;98:643–651. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghmans S, Murphey RD, Wienholds E, Neuberg D, Kutok JL, Fletcher CD, Morris JP, Liu TX, Schulte-Merker S, Kanki JP, Plasterk R, Zon LI, Look AT. tp53 mutant zebrafish develop malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:407–412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406252102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake T, Adya N, Kim CH, Oates AC, Zon L, Chitnis A, Weinstein BM, Liu PP. Zebrafish homolog of the leukemia gene CBFB: its expression during embryogenesis and its relationship to scl and gata-1 in hematopoiesis. Blood. 2000;96:4178–4184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Snir M, Noushmehr H, Kirby M, Hong SK, Elkahloun AG, Feldman B. Transcriptional profiling of endogenous germ layer precursor cells identifies dusp4 as an essential gene in zebrafish endoderm specification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12337–12342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805589105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns CE, DeBlasio T, Zhou Y, Zhang J, Zon L, Nimer SD. Isolation and characterization of runxa and runxb, zebrafish members of the runt family of transcriptional regulators. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:1381–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campodonico E, Schwer B. ATP-dependent remodeling of the spliceosome: intragenic suppressors of release-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Prp22. Genetics. 2002;160:407–415. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhang L, Jones KA. SKIP counteracts p53-mediated apoptosis via selective regulation of p21Cip1 mRNA splicing. Genes & development. 2011;25:701–716. doi: 10.1101/gad.2002611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Company M, Arenas J, Abelson J. Requirement of the RNA helicase-like protein PRP22 for release of messenger RNA from spliceosomes. Nature. 1991;349:487–493. doi: 10.1038/349487a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JL, Zon LI. Use of the zebrafish system to study primitive and definitive hematopoiesis. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:481–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.095931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson H, Wheatley SP, Morrison CG. Involvement of centrosome amplification in radiation-induced mitotic catastrophe. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:364–370. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.3.3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JL, Zon LI. Ontogeny of hematopoiesis: examining the emergence of hematopoietic cells in the vertebrate embryo. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2003;53:139–158. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)53004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome biology. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126:3735–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffredo T, Gautier R, Eichmann A, Dieterlen-Lievre F. Intraaortic hemopoietic cells are derived from endothelial cells during ontogeny. Development. 1998;125:4575–4583. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Xu J, Wen Z. Migratory path of definitive hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells during zebrafish development. Blood. 2007;109:5208–5214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalev-Zylinska ML, Horsfield JA, Flores MV, Postlethwait JH, Vitas MR, Baas AM, Crosier PS, Crosier KE. Runx1 is required for zebrafish blood and vessel development and expression of a human RUNX1-CBF2T1 transgene advances a model for studies of leukemogenesis. Development. 2002;129:2015–2030. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler R, Putz G, Pelletier L, Poser I, Heninger AK, Drechsel D, Fischer S, Konstantinova I, Habermann B, Grabner H, Yaspo ML, Himmelbauer H, Korn B, Neugebauer K, Pisabarro MT, Buchholz F. An endoribonuclease-prepared siRNA screen in human cells identifies genes essential for cell division. Nature. 2004;432:1036–1040. doi: 10.1038/nature03159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli G, Clelland E, Peng C. Potential targets of transforming growth factor-beta1 during inhibition of oocyte maturation in zebrafish. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2005;3 doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cell fate. Oncogene. 2002;21:3262–3269. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Ferrando AA, Traver D, Kutok JL, Hezel JP, Kanki JP, Zon LI, Look AT, Trede NS. In vivo tracking of T cell development, ablation, and engraftment in transgenic zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7369–7374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402248101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langheinrich U, Hennen E, Stott G, Vacun G. Zebrafish as a model organism for the identification and characterization of drugs and genes affecting p53 signaling. Curr Biol. 2002;12:2023–2028. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson ND, Weinstein BM. In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2002;248:307–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke GJ, Oates AC, Crowhurst MO, Ward AC, Layton JE. Morphologic and functional characterization of granulocytes and macrophages in embryonic and adult zebrafish. Blood. 2001;98:3087–3096. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke GJ, Oates AC, Paw BH, Thompson MA, Hall NE, Ward AC, Ho RK, Zon LI, Layton JE. Zebrafish SPI-1 (PU.1) marks a site of myeloid development independent of primitive erythropoiesis: implications for axial patterning. Dev Biol. 2002;246:274–295. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons SE, Lawson ND, Lei L, Bennett PE, Weinstein BM, Liu PP. A nonsense mutation in zebrafish gata1 causes the bloodless phenotype in vlad tepes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5454–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082695299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayas RM, Maita H, Staley JP. Exon ligation is proofread by the DExD/H-box ATPase Prp22p. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:482–490. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvinsky A, Dzierzak E. Definitive hematopoiesis is autonomously initiated by the AGM region. Cell. 1996;86:897–906. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Kissa K, Zapata A, Mordelet E, Briolat V, Lin HF, Handin RI, Herbomel P. Tracing hematopoietic precursor migration to successive hematopoietic organs during zebrafish development. Immunity. 2006;25:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North TE, de Bruijn MF, Stacy T, Talebian L, Lind E, Robin C, Binder M, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 expression marks long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells in the midgestation mouse embryo. Immunity. 2002;16:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M, Shimura Y. A human RNA helicase-like protein, HRH1, facilitates nuclear export of spliced mRNA by releasing the RNA from the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 1996;10:997–1007. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T, Nishimura M, Nakao M, Fujita Y. RUNX1/AML1: a central player in hematopoiesis. Int J Hematol. 2001;74:252–257. doi: 10.1007/BF02982057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Ohno M, Shimura Y. Identification of a putative RNA helicase (HRH1), a human homolog of yeast Prp22. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7611–7620. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patan S. Lycat and cloche at the switch between blood vessel growth and differentiation? Circ Res. 2008;102:1005–1007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei W, Noushmehr H, Costa J, Ouspenskaia MV, Elkahloun AG, Feldman B. An early requirement for maternal FoxH1 during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2007;310:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom DG, Bahary N, Niss K, Traver D, Burns C, Trede NS, Paffett-Lugassy N, Saganic WJ, Lim CA, Hersey C, Zhou Y, Barut BA, Lin S, Kingsley PD, Palis J, Orkin SH, Zon LI. The zebrafish moonshine gene encodes transcriptional intermediary factor 1gamma, an essential regulator of hematopoiesis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom DG, Haffter P, Odenthal J, Brownlie A, Vogelsang E, Kelsh RN, Brand M, van Eeden FJ, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Hammerschmidt M, Heisenberg CP, Jiang YJ, Kane DA, Mullins MC, Nusslein-Volhard C. Characterization of zebrafish mutants with defects in embryonic hematopoiesis. Development. 1996;123:311–319. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Campodonico E, Schwer B. Motifs IV and V in the DEAH box splicing factor Prp22 are important for RNA unwinding, and helicase-defective Prp22 mutants are suppressed by Prp8. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8617–8626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Hotz HR, Schwer B. Characterization of dominant-negative mutants of the DEAH-box splicing factors Prp22 and Prp16. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15452–15458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B. A conformational rearrangement in the spliceosome sets the stage for Prp22-dependent mRNA release. Mol Cell. 2008;30:743–754. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Gross CH. Prp22, a DExH-box RNA helicase, plays two distinct roles in yeast pre-mRNA splicing. Embo J. 1998;17:2086–2094. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Meszaros T. RNA helicase dynamics in pre-mRNA splicing. Embo J. 2000;19:6582–6591. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Speed T. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods. 2003;31:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainier DY, Weinstein BM, Detrich HW, 3rd, Zon LI, Fishman MC. Cloche, an early acting zebrafish gene, is required by both the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Development. 1995;121:3141–3150. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Schwer B. Characterization of the NTPase, RNA-binding, and RNA helicase activities of the DEAH-box splicing factor Prp22. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9795–9803. doi: 10.1021/bi050407m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MA, Ransom DG, Pratt SJ, MacLennan H, Kieran MW, Detrich HW, 3rd, Vail B, Huber TL, Paw B, Brownlie AJ, Oates AC, Fritz A, Gates MA, Amores A, Bahary N, Talbot WS, Her H, Beier DR, Postlethwait JH, Zon LI. The cloche and spadetail genes differentially affect hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis. Dev Biol. 1998;197:248–269. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel R, Kassen SC, Montgomery JE, Enright JM, Hyde DR. Inhibition of Muller glial cell division blocks regeneration of the light-damaged zebrafish retina. Developmental neurobiology. 2008;68:392–408. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeli KM, Jin SW, Martin GR, Stainier DY. A common progenitor for haematopoietic and endothelial lineages in the zebrafish gastrula. Nature. 2006;443:337–339. doi: 10.1038/nature05045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein BM, Schier AF, Abdelilah S, Malicki J, Solnica-Krezel L, Stemple DL, Stainier DY, Zwartkruis F, Driever W, Fishman MC. Hematopoietic mutations in the zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:303–309. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M, ZFIN . The zebrafish book a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish Danio (Brachydanio) rerio. ZFIN; Eugene, Or: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Willett CE, Cortes A, Zuasti A, Zapata AG. Early hematopoiesis and developing lymphoid organs in the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:323–336. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199904)214:4<323::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong JW, Yu Q, Zhang J, Mably JD. An acyltransferase controls the generation of hematopoietic and endothelial lineages in zebrafish. Circ Res. 2008;102:1057–1064. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.163907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoong S, O'Connell B, Soanes A, Crowhurst MO, Lieschke GJ, Ward AC. Characterization of the zebrafish matrix metalloproteinase 9 gene and its developmental expression pattern. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.