Abstract

Several cholangiopathies result from a perturbation of developmental processes. Most of these cholangiopathies are characterised by the persistence of biliary structures with foetal configuration. Developmental processes are also relevant in acquired liver diseases, as liver repair mechanisms exploit a range of autocrine and paracrine signals transiently expressed in embryonic life. We briefly review the ontogenesis of the intra and extrahepatic biliary tree, highlighting the morphogens, growth factors and transcription factors that regulate biliary development, and the relationships between developing bile ducts and other branching biliary structures. Then we discuss the ontogenetic mechanisms involved in liver repair, and how these mechanisms are recapitulated in ductular reaction, a common reparative response to many forms of biliary and hepatocellular damage. Finally, we discuss the pathogenic aspects of the most important primary cholangiopathies related to altered biliary development i.e. polycystic and fibropolycystic liver diseases, Alagille syndrome.

Introduction

Development of the biliary system is a unique process that has been thoroughly reviewed in several recent papers1,2. Here, we will focus on those concepts of biliary development that are “essential” to understand congenital and acquired cholangiopathies.

Cholangiopathies are an heterogeneous group of liver diseases, caused by congenital, immune-mediated, toxic, infectious or idiopathic insults to the biliary tree3,4. In addition to being responsible for significant morbidity and mortality, cholangiopathies account for the majority of liver transplants in paediatrics and a significant percentage of liver transplants in young adults. Many cholangiopathies are congenital, resulting initially from an altered development of the biliary tree, eventually accompanied by necro-inflammatory processes5,6. For the clinical hepatologist, this means a good working knowledge of the mechanisms of liver development is necessary for the care of these patients.

We will briefly review the general aspects of bile duct development and morphogenesis and the main molecular mechanisms involved in bile duct ontogenesis. Then we will highlight the role of these mechanisms in liver repair. Lastly, we will discuss the cholangiopathies related to altered development, with a special emphasis on those caused by a single genetic defect.

General aspects of bile duct morphogenesis during liver development

The liver develops as a tissue bud deriving from a diverticulum of the ventral foregut endoderm, which extends into the septum transversum, a structure located between the pericardial and peritoneal cavities. The ventral foregut endoderm develops two protrusions: the cranial part leads to the formation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, while the caudal part generates the extrahepatic biliary tree1,7,8.

Intrahepatic biliary tree

The development of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium begins around the 8th week of gestation (GW), and proceeds centrifugally from the hilum to the periphery of the liver following the portal vein system5,6,9. At birth the intrahepatic biliary epithelium is still immature, and its maturation is completed during the first years of life9. The sequence of events leading to the development of the ductal plate and the intrahepatic bile ducts are shown in Figure 110–12. Whether or not segments of the ductal plate that are not incorporated into the nascent bile ducts, are gradually deleted by apoptosis is a matter of controversy. Recent data from Lemaigre’s group13 suggest that ductal plate remodeling does not occur by proliferation and apoptosis. Rather, portions of the ductal plate appear to differentiate into periportal hepatocytes and adult hepatic progenitor cells13. The role of ductal plate cells as potential stem cells has been recently addressed by Furuyama et al.14. A crucial event in the development of the intrahepatic biliary system, as well as in liver repair, is tubulogenesis. Biliary tubule formation depends upon a unique process of transient asymmetry. Careful studies performed in mouse embryos have shown that nascent tubules are formed by ductal plate cells resembling cholangiocytes (positive for the SRY-related HMG box transcription factor 9 [Sox9] and cytokeratin-19 [K19]) on the side facing the portal tract, and by ductal plate cells resembling hepatoblasts (positive for the hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 [HNF4] and the transforming growth factor receptor type II [TβRII]) on the side facing the parenchyma. The “portal” layer shows higher levels of E-cadherin and is in contact with laminin, while the “parenchymal” layer is characterised by the apical expression of osteopontin15. After the formation of a lumen, the nascent bile duct becomes symmetrical as “hepatoblasts” are replaced by “cholangiocytes”, and the ductal structure matures along a cross-sectional axis and a cranio-caudal axis, extending from the hilum to the periphery. Thus, the progressive elongation of the duct requires a mechanism able to orient cell mitoses along the aforementioned axes in a coordinated manner. Through this mechanism, called “planar cell polarity” (PCP), the epithelial cells are uniformly oriented within the ductal plane to maintain the tubular architecture. PCP is a process that is controlled by the non-canonical Wnt pathway, and is defective in fibropolycystic liver diseases (see below)16.

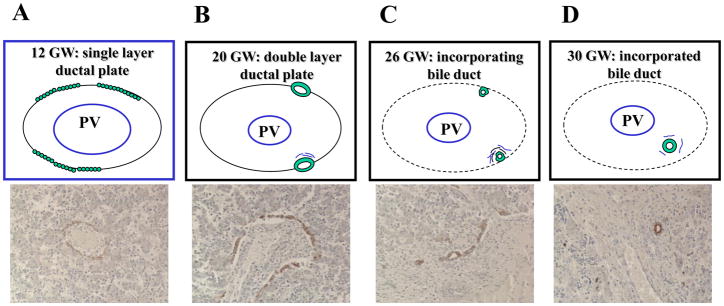

Figure 1. Embryological stages of intrahepatic bile duct development.

The development of intrahepatic bile ducts starts when the periportal hepatoblasts, in close contact with the portal mesenchyme surrounding a portal vein branch, begin to organise into a single layered sheath of small flat epithelial cells, called ductal plate (“ductal plate stage”, A). In the following weeks, discreet portions of the ductal plates are duplicated by a second layer of cells (double layered ductal plate, B), which then dilate to form tubular structures in the process of being incorporated into the mesenchyma of the nascent portal space (incorporating bile duct, “migratory stage”, C). Once incorporated into the portal space, the immature tubules are remodeled into individualised bile ducts (incorporated bile duct, “bile duct stage”, D).

The mechanisms that regulate the termination of biliary development are not well known. Recent work from Kaestner’s laboratory suggests that by inhibiting NF-κB-dependent cytokine expression (specifically IL-6), the transcription factors Foxa1/2, may act as a termination signal in bile duct development. Mice with liver-specific deletion of both Foxa1 and Foxa2 showed an increased amount of dysmorphic bile ducts17. On the other hand, a decrease in Notch signaling could change the fate of the non-duplicated ductal plate segments18 and promote their differentiation towards alternative pathways.

Extrahepatic biliary tree

Cholangiocytes lining the extrahepatic bile ducts derive from the caudal part of the ventral foregut endoderm located between the liver and the pancreatic buds, a region that expresses a combination of transcription factors common to the pancreas and duodenum (Pdx-1, Prox-1, HNF-6). The extrahepatic part of the biliary tree develops before the intrahepatic part; the two systems merge at the level of the hepatic duct/hilum. Molecular mechanisms regulating the development of the extrahepatic bile ducts are less well known than those regulating the development of the intrahepatic bile ducts. Mice deficient in Pdx-119 or Hes1 (a Notch-dependent transcription factor), HNF6, HNF-1β, or Foxf1 (a transcription factor target for the sonic Hedgehog signaling) results in an altered development of the gallbladder and of the common bile duct20–22.

Relationships between biliary and arterial development

Branches of the hepatic artery develop in close proximity to ductal plates. On one side, the biliary epithelium guides arterial development, on the other, the developing intrahepatic bile ducts are nourished by the peribiliary plexus (PBP), a network of capillaries emerging from the finest branches of the hepatic artery at the periphery of the liver lobule. PBP is crucial in maintaining the integrity and function of the biliary epithelium23–25.

The patterning of the intrahepatic biliary tree develops in strict harmony with hepatic arteriogenesis. For example, inactivation of Hnf6 or Hnf1β, transcription factors involved in intrahepatic bile duct epithelium development, resulted in anomalies of hepatic artery branches paralleling bile duct abnormalities1,12. One of the signals linking ductal and arterial development in the liver is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which cooperates with Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1). The developing bile ducts produce VEGF-A that in turn acts on endothelial cells and their precursors, which both express the receptor VEGFR-2, to promote arterial and PBP vasculogenesis. At the same time, Ang-1 produced by hepatoblasts, is likely to induce the maturation of hepatic artery terminations by recruiting mural pericytes to the nascent endothelial layer12. In ductal plate malformations (DPM), the dysmorphic bile ducts are surrounded by an increased number of vascular structures5,26,27. For example, in cystic cholangiopathies, the epithelium retains an immature phenotype typical of the embryonic ductal plate coupled with the production of VEGF and angiopoietins26. Production of angiogenic factor by immature cholangiocytes promotes an abundant pericystic vascularisation, thus providing the vascular supply around the growing liver cysts27 (see below).

The anatomical and functional association between bile ductules and arterial vascularisation is maintained also in adult life and during liver repair. A malfunction of this system may cause ductopenia, as observed in chronic allograft rejection and in other chronic cholangiopathies caused by an ischemic damage28. Ductular reaction is a common histopathological response to many forms of liver damage (see below); the increase in bile ductules at the portal tract interface is paralleled by an increased number of hepatic arterioles and capillaries24,25. These features are reproduced in an experimental rat model of selective cholangiocyte proliferation (α-naphthylisothiocyanate treatment), where an extensive neovascularisation of the arterial bed develops in strict conjunction with increased cholangiocyte mass29. Furthermore, expansion of the biliary tree after bile duct ligation in rat is also followed by substantial adaptive modifications of the PBP25,30.

Transcription factors, growth factors and morphogens involved in the ontogenesis of the biliary epithelium

At the time of liver specification, i.e. when the endoderm becomes committed towards a liver cell fate, liver development is driven by several transcription factors including hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β (HNF1β)21,31, Foxa1 and Foxa232, and GATA-433–35. Extracellular signals, like fibroblast growth factor (FGF) secreted by the cardiogenic mesoderm36, bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP-4) and extracellular matrix constituents34,36, signal to competent cells and appear also to be involved in biliary differentiation.

The differentiation of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium and its tubular morphogenesis are finely regulated by signals exchanged between epithelial cells and a variety of other non-parenchymal cells. These signals encompass a series of morphogens and growth factors that regulate the commitment of hepatoblasts to the biliary lineage, or tubule formation by cholangiocytes, or more often, both processes. The portal mesenchyme generates a portal to parenchymal gradient of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β2 and TGF-β3). TGF-β stimulates hepatoblasts to undergo a switch towards a biliary phenotype37. The developing ductal plates transitorily express the TGF-β-receptor type II (TβRII); expression of TβRII is repressed in differentiated cholangiocytes.

HNF6 and HNF1β are transcription factors able to regulate multiple steps of biliary development and morphogenesis. Their expression is up-regulated in cholangiocytes and in progenitor cells committed to the cholangiocyte lineage. In mice, their absence is associated with cystic dysgenesis of the biliary tree21,38. HNF6 and HNF1β regulate distinct stages of bile duct morphogenesis. Whereas the absence of HNF6 caused an early defect in biliary cell differentiation, which can be somehow repaired, a defect in HNF1β appears to be associated with a defect in the maturation of the primitive ductal structure39. Furthermore, HNF6 stimulates expression of Pkhd1 while a deletion of HNF1β causes an aberrant cystic development and defects in PCP, a feature associated with fibropolycystic liver diseases16. It is noteworthy that HNF1β expression appears to be under the control of Notch signaling.

Notch signaling is a fundamental mechanism that confers cell fate instructions during the development of various tissues. Several studies using genetic mouse models and zebrafish, demonstrated that Notch signaling is required at different stages during biliary tree development: from the formation of the ductal plate to ductal plate remodeling and tubule formation40,41. The Notch genes encode for four transmembrane receptors (Notch 1, 2, 3 and 4), which can interact with a number of ligands (Jagged-1, Jagged-2, Delta-like 1, 3 and 4). Notch signaling requires the establishment of cell-cell contacts. Through this interaction among neighboring cells, Notch receptors expressed by “receiving” cells are activated by the binding of ligands expressed on the surface of “transmitting” cells. Notch may stimulate cells to undergo a phenotypic switch through a process of “lateral induction”. Alternatively, Notch may promote the maintenance of the original phenotype through “lateral inhibition”42. In liver development, Notch signaling appears to control the ability of hepatoblasts and mature hepatocytes to differentiate into cholangiocytes by altering the expression of liver-enriched transcription factors, and to regulate the formation of biliary tubules18. Notch-dependent signaling mechanisms are summarised in Figure 2. Notch drives the activation of Notch effector genes such as Hairy and Enhancer of Split homologs (Hes1 and Hey-1), via the transcription factor recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J (RBP-Jk), which in turn activates transcription factors specifically expressed by cholangiocytes, including HNF1β and Sox943.

Figure 2. Notch signaling.

Jagged binding to a Notch receptor leads to the proteolytic processing and subsequent translocation into the nucleus of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) of the receptor. Cleavage of NICD is an essential step in this process and is mediated by a γ-Secretase enzyme in the cytoplasm. Once delivered into the nucleus, NICD forms a complex with its DNA-binding partner, the recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J (RBP-Jk). The formation of this complex leads to the up-regulation of cholangiocyte-specific transcription factors, such as HNF1β and the SRY-related HGM box transcription factor 9 (Sox9), and to the down-regulation of hepatocyte-specific transcription factors such as HNF1α and HNF4. Sox9 in particular, is the most specific and earliest marker of biliary cells in developing liver, as it controls the timing and maturation of primitive ductal structures in tubulogenesis.

Studies in mice have shown that Jagged-1 is expressed by periportal mesenchymal cells, and interacts with Notch-2 expressed by hepatoblasts favouring their differentiation into ductal plate cells. Perturbations in Jagged-1/Notch-2 interactions cause Alagille syndrome (AGS), a genetic cholangiopathy characterised by ductopenia and defective peripheral branching of the biliary tree44. In fact, Jagged-1 inactivation in the portal vein mesenchymal cells, but not in the endothelial cells, results in a defective development of the bile ducts that do not mature beyond the initial formation of the ductal plate45.

A major effect of Notch signaling is to modulate tubule formation, a property that is necessary to effectively repair the biliary tree. The effects of Notch receptors can be modified by other ligands such as the glycosyltransferases encoded by Fringe genes, and by the dosage of the Jagged-1 gene46. The impact of Notch signaling on the intrahepatic bile duct branching is highlighted by a recent study by Sparks et al.47, which demonstrated that the density of three-dimensional peripheral intrahepatic bile duct architecture during liver development depends on Notch gene dosage.

Canonical Wingless (Wnt)/β-catenin participates in several stages of bile duct development. Specific Wnt ligands, such as Wnt3a, induce biliary differentiation, characterised by the appearance of K19 positivity and generation of duct-like structures in mouse embryonic liver cell cultures. Wnt/β-catenin appears to play a key role in biliary commitment, by repressing hepatocyte differentiation and promoting ductal plate remodeling1,2. The deletion of β-catenin in the developing hepatoblasts in transgenic mice leads to a paucity of bile ducts and to multiple defects in hepatoblast maturation, expansion, and survival48. Wnt can also signal through β-catenin-independent pathways. Non-canonical Wnt pathways seem to be crucial in the regulation of PCP49, which is lost when Pkhd1, the gene encoding for fibrocystin (see below), is defective16. Notably, inversin, a cilium-associated protein regulating the left-right symmetry, modulates non-canonical Wnt signaling by interacting directly with Dvl50 and if defective, causes aberrant development of intrahepatic bile ducts and cyst formation16. Canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways are illustrated in Figure 3.

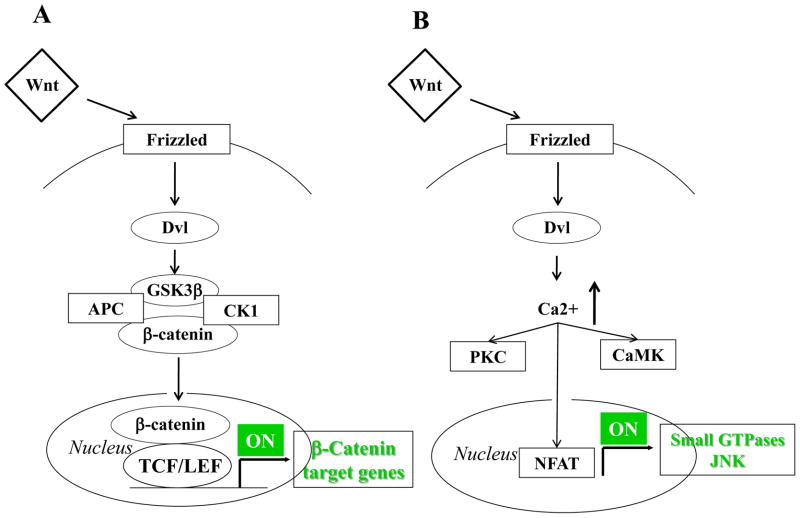

Figure 3. Wnt signaling (canonical and non-canonical).

Wnt signals in two different ways depending upon the activation (canonical) or the non-activation (non canonical) of β-catenin. In the canonical Wnt pathway (A), the binding of Wnt to Frizzled (Fzd) receptors activates Dishevelled (Dvl), which prevents the phosphorylation and the following ubiquitination of β-catenin. If β-catenin is not phosphorylated, it can thus accumulate in the cytoplasm and then translocate to the nucleus, where it activates Wnt target genes by interacting with the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors. In the non-canonical Wnt pathway (B), the binding of specific Wnt isoforms (Wnt 4, 5a, 11) to Fzd can activate Dvl but the downstream signal pathways involve small GTPases and the C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) instead of β-catenin. Once activated, Dvl leads to increased intracellular Ca2+ levels that activate a number of proteins, including PKA, CaMK and NFAT. Acting as transcription factors, these proteins may activate downstream effectors that are crucial regulators of different cellular responses, such as planar cell polarity and cytoskeletal rearrangement.

Similar to Notch and Wnt, Hedgehog signaling (Hh) is a morphogenetic pathway involved in liver development. Signaling mechanisms of the Hh pathway are shown in Figure 4. On the contrary to stromal and progenitor cells, mature epithelial cells do not retain the ability to respond to Hh signals. During development, sonic Hh is expressed in the ventral foregut endoderm, but its expression is then down-regulated when the liver bud is formed51. In the foetal liver, Hh and Gli1, a transcription factor, downstream of Hh signaling, are expressed in liver progenitor cells but their expression disappears as soon as the development proceeds. Therefore, activation of Hh signals is requested in a temporally restricted manner to promote the early hepatoblast proliferation, but then this pathway needs to be switched off to allow hepatoblasts to differentiate normally51.

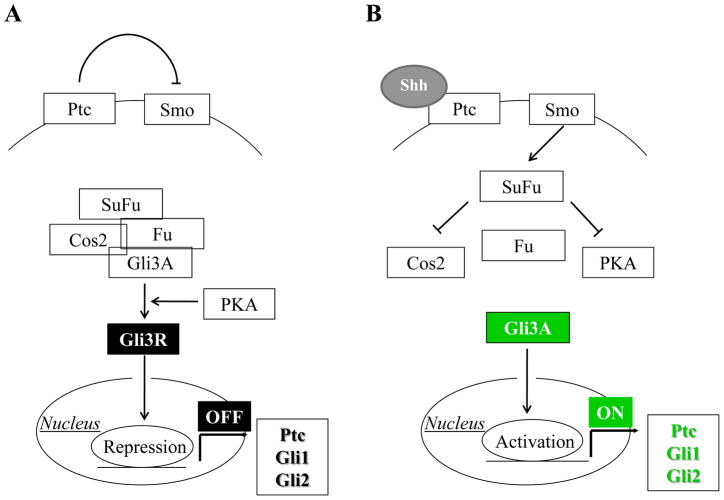

Figure 4. Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling.

In physiological conditions (A), Patched (Ptc) receptor binds to and consequently suppresses the function of its co-receptor Smoothened (Smo). This maintains the bonding of the downstream regulator Glioblastoma-3 (Gli3) to a tetramer complex encompassing its suppressor factors, Suppressor Fused (Su(Fu)), Costal2 (Cos2), and Fused (Fu). In this complex, Gli3 is proteolytically cleaved by Protein Kinase A (PKA), and converted into the repressor form (Gli3R), which exerts an inhibitory effect on nuclear transcription factors regulating Hh-responsive genes (Ptc, Gli1, Gli2). When Shh interacts with Ptc (B), it prevents its inhibitory action on Smo. Following Smo activation, the tetramer complex is disassembled so that Su(Fu) inhibitory effect is restricted to Cos2 and PKA, and thereby preventing the proteolytic cleavage of Gli3. Gli3 can thus enter the nucleus in the activated state (Gli3A) to promote activation of Hh target genes.

In addition to differentiation and tissue remodeling, biliary tubulogenesis requires cell proliferation. While the process of remodeling depends on complex interactions with mesenchymal and endothelial cells, tubule elongation is stimulated by a number of paracrine or autocrine factors, including oestrogens52, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1)53,54, interleukin-6 (IL-6)55, VEGF26, which are able to stimulate cholangiocyte proliferation.

When tubule formation finishes, cholangiocytes become quiescent. Expression of ciliary proteins and control of cytokine secretion are important mechanisms involved in the termination of the developmental process. Foxa1 and Foxa2 are liver-specific transcription factors, which play a crucial role in establishing the developmental competence of the foregut endoderm and liver specification32. Interestingly, mice with liver-specific deletion of Foxa1/2 develop dysmorphic and dilated bile ducts surrounded by increased portal fibrosis. These changes are, in part, caused by the persistent expression of IL-6 by the biliary epithelium. In fact, the IL-6 promoter is negatively regulated by Foxa1/2 through binding to the glucocorticoid receptor. In absence of Foxa1/2, IL-6 expression is not suppressed leading to both autocrine effects on cholangiocytes (proliferation) and to paracrine effects on inflammatory cells and myofibroblasts (peribiliary fibrosis)32. This observation suggests that Foxa1/2 are among the transcription factors involved in the termination of bile duct development. Given the strong ability of reactive cholangiocytes to secrete large amounts of IL-6, this mechanism can be relevant also in liver repair (see below).

Ductular reaction, a reparative response to biliary and hepatocellular damage, is characterised by features reminiscent of biliary ontogenesis

Mechanisms of liver repair recapitulating liver developmental processes is an emerging concept. In fact, many molecular factors (growth factors, transcription factors, morphogens) transiently engaged in the development of the biliary epithelium during embryonic life, are reactivated in adulthood in response to acute or chronic liver damage12,56.

In the adult liver, the division of mature epithelial cells i.e. hepatocytes and/or cholangiocytes, drives normal tissue homeostasis and regeneration after acute and transient hepatocellular or biliary damage. On the other hand, in chronic liver diseases, liver repair relies on the activation of hepatic progenitor cells (HPC). HPC are bipotent cells located in close proximity to the terminal cholangioles at their interface with the canals of Hering. HPC are able to amplify and differentiate into cells committed to hepatocellular or biliary lineages57–60. In humans, differentiation towards hepatocytes occurs via intermediate hepato-biliary cells (IHBC), whereas differentiation towards the biliary lineage leads to the formation of reactive ductules (RDC)60. These cellular elements encompass the “hepatic reparative complex” and can be recognised from their expression of cytokeratin-7 (K7) and/or −19 (K19), cytoskeletal proteins present in the biliary lineage, but not in hepatocytes (Figure 5)9,56. Although transdifferentiation from hepatocytes (formerly recognised as “ductular metaplasia” of hepatocytes) may occur under certain circumstances, reactive ductules are believed to derive mostly from the progenitor cell compartment.

Figure 5. Epithelial phenotypes involved in liver repair driven by the activation of hepatic progenitor cells (“Hepatic Reparative Complex”).

In acute and chronic liver diseases, especially in fulminant hepatic failure, liver repair is driven by the activation of hepatic progenitor cells (HPC) to differentiate into hepatocytes and/or cholangiocytes. However, hepatocyte and cholangiocyte proliferation can be directly stimulated without exploiting HPC activation in experimental models, such as partial hepatectomy and acute biliary obstruction, respectively. HPC are small epithelial cells with an oval nucleus and scant cytoplasm, similar to oval cells in rodents treated with carcinogens. HPC originate from a niche located in the smaller branches of the biliary tree and in the canals of Hering. HPC behave as a bipotent, transit amplifying compartment. Differentiation of HPC towards hepatocytes occurs via intermediate hepatobiliary cells (IHBC), whilst differentiation towards the biliary lineage leads to the formation of reactive ductular cells (RDC). HPC, IHBC and RDC constitute the “hepatic reparative complex”, and can be distinguished by morphology and pattern of K7 expression. Whereas Wnt signaling is a key regulator of proliferation of HPC, Notch and Hh signaling are mostly involved in biliary differentiation through RDC generation, along with other cytokines released from the inflammatory microenvironment (TNF-α, TWEAK, TGF-β, HGF, VEGF, IL-6) (see text for details).

Initially, RDC organise in clusters and do not encircle a lumen. As RDC’s participation in tissue remodeling develops, they eventually reorganise into a richly anastomosing tubular network. Tubule formation during biliary repair is a fundamental process aimed at generating a compensatory increase of the ductal mass to prevent the development of extensive liver necrosis due to the leakage of bile into the parenchyma. It is important to recognize that activation and proliferation of HPC is not sufficient to repair biliary damage unless progenitor cells and reactive cholangiocytes acquire the ability to form new branching tubular structures, thus restoring the ductal mass61.

In addition to replacement of damaged cells and development of branching tubules, liver repair requires the generation of a fibro-vascular stroma able to sustain and feed the remodeling ductal structures. As a consequence, RDC de novo express a variety of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, angiogenic factors and adhesion molecules, along with their receptors. This property enables RDC to establish an extensive cross-talk with other liver cell types, including hepatocytes, stellate cells and endothelial cells (Figure 6)62. When the biliary tree is damaged, these interactions become functionally relevant leading to a significant expansion of the reactive cholangiocyte compartment. Most of the molecular signatures expressed by reactive cholangiocytes, including VEGF12, TGF-β263, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)64, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)65, IL-666, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα)66, neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and Bcl-256, are transiently expressed by ductal plate cells in foetal life, consistent with the concept that ductular reaction recapitulates liver ontogenesis56,67–69 (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Reactive ductular cells acquire the ability to exchange a range of paracrine signals with mesenchymal, vascular and inflammatory cells.

Owing to the de novo expression of a variety of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, angiogenic factors, together with a rich expression of many of the respective cognate receptors, reactive ductular cells can establish an extensive cross-talk with other liver cell types, particularly with stellate cells, endothelial cells and inflammatory cells. In response to biliary damage, these interactions becomes functionally relevant leading to the generation of a fibro-vascular stroma able to sustain and feed the ductular reaction, and to the recruitment of a peribiliary inflammatory infiltrate which further enhances the bile duct damage.

Figure 7. Phenotypic changes of ductular reactive cells shared with ductal plate cells.

An important feature of reactive cholangiocytes is the foetal reminiscence of their phenotype. Reactive ductular cells express neuroendocrine features, adhesion molecules, cytokines and chemokines, receptors and other metabolically active molecules, which are transiently expressed by ductal plate cells during embryonic development.

The molecular mechanisms that activate ductular reaction require a finely coordinated process that also shares a number of similarities with biliary embryogenesis. Ductular reaction is elicited by inflammatory signals released from the local microenvironment. TNFα70, TWEAK71, TGF-β72, HGF72, VEGF26,73, sonic Hedgehog (shh)74, and Wnt/β-catenin75 signaling are among the key signaling pathways. As mentioned above, proliferation of reactive cholangiocytes may be achieved by switching off transcription factors (Foxa1/2) used to terminate development. Unfortunately, activation/deactivation of developmental mechanisms in the context of non-resolving inflammation, leads to the development of portal fibrosis in cholangiopathies. The ability of “reactive” cholangiocytes to recruit inflammatory, vascular and mesenchymal cells, with which they exchange a variety of paracrine signals, subsequently leads to excessive collagen deposition and stimulation of angiogenesis, and ultimately to cirrhosis76.

Several morphogens involved in biliary development, such as Wnt, Hedgehog, and Notch, also play a pivotal role in liver repair. Recent findings suggest that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is strongly involved in the normal activation and proliferation of adult HPC in both acute and chronic human liver diseases77. Oval cell activation in β-catenin conditional knockout mice was dramatically reduced, after chemical treatment to induce acute liver damage78.

Whereas Wnt signaling is a key regulator of proliferation of HPC, Notch signaling is mostly involved in biliary differentiation. The role of Notch is underscored by the peculiar liver phenotype observed in AGS. AGS is characterised by a marked reduction in RDC and HPC, in sharp contrast with biliary atresia, which is a congenital cholangiopathy with similar levels of homeostasis but much faster evolution to biliary cirrhosis79. This difference is likely related to a Notch-dependent block in cell fate determination upstream of HNF1β. Recent data from our group show that following treatment with cholestatic agents, HPC activation and tubule formation are dramatically impaired in mice with a liver-specific defect in RBP-Jk80.

In addition to Notch, Hh signaling is also relevant in congenital cholangiopathies. Perturbations in the Hh signaling have been associated with DPM in Meckel syndrome (MKS), a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by a defect in MKS1 gene encoding a protein associated with the base of cilia. MKS causes perinatal lethality and is characterised by a complex syndrome including polycystic kidneys, occipital meningoencephalocele, postaxial polydactyly in addition to DPM81. In liver repair, activation of the Hh signaling promotes the expansion of a subset of immature ductular cells that co-express mesenchymal markers and may be profibrogenic82. This mechanism is relevant in biliary atresia, where excessive activation of Hh signaling halts bile duct morphogenesis and promotes accumulation of immature ductular cells with a mesenchymal phenotype, which in turn enhance fibrogenesis83. These data suggest that aberrant activation of Hh signaling may be responsible for biliary fibrosis featuring developmental cholangiopathies.

Primary cholangiopathies related to an altered development of the biliary epithelium

Cholangiopathies related to altered biliary development5,84 (Table 1) represent important disease models; understanding their pathogenetic mechanisms offers important clues on how specific genes regulating developmental processes are involved in biliary repair and reaction to damage. Recently, based on the phenotype of several mouse models with specific defects of biliary morphogenesis, DPM have been classified into three groups, with: a) defective differentiation of biliary precursors cells (HNF6 deficiency), b) defective maturation of primitive ductal structure (HNF1β deficiency) or c) defective duct expansion during development with preserved biliary differentiation (cystin-1 deficiency)39. Most DPM are embryonically lethal or are part of complex syndromic diseases. Herein, we will outline the most recent advances in the pathogenesis of congenital cholangiopathies that may be clinically relevant for both paediatric and adult clinical hepatologists. The most common DPM are the Von Meyenburg complexes, also known as biliary microhamartomas (see Figure 8B). These are benign lesions characterised by irregularly shaped and dilated biliary structures, embedded in a dense fibrous stroma. Their distribution is generally focal, but when diffuse they can be associated with cystic lesions, as seen in congenital hepatic fibrosis (see below) 6. Von Meyenburg complexes have also been found in higher numbers in the liver of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease85,86. The association of Von Meyenburg complexes to cholangiocarcinoma is uncommon, but it has been sporadically described87–89.

Table 1.

Primary Cholangiopathies related to Altered Biliary Development

| GROUP | DISEASE | GENE DEFECT | LIVER PHENOTYPE | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ductopenic syndromes | AGS | Jagged1 Notch2 | Ductopenia, reduced HPC and RDC, increased IHBC, mild portal fibrosis | Pruritus Jaundice Failure to thrive |

| Malformative syndromes associated to DPM | Meckel syndrome | MKS1 | Ductal plate remnants | Abort or perinatal death |

| Joubert syndrome | MKS3 and others | Ductal plate remnants | Abort or perinatal death | |

| Polycystic liver diseases | ADPKD | PKD1 PKD2 | Liver cysts without peribiliary fibrosis | Cyst complications Mass effect Malnutrition Renal failure |

| PLD | PRKCSH SEC63 | Liver cysts without peribiliary fibrosis | Cyst complications Mass effect Malnutrition |

|

| Fibropolycystic liver diseases | ARPKD, CHF, CD | PKHD1 | Biliary microhamartomas with peribiliary fibrosis | Acute cholangitis Intrahepatic lithiasis Portal hypertension Risk for evolution to CCA |

Figure 8. Main differences in liver phenotype between ARPKD and ADPKD.

On magnetic resonance imaging, liver cysts appear as focal lesions with regular margins, which are of small size and in continuity with the biliary tree in ARPKD (A), whereas they are large, of different size and scattered throughout the hepatic parenchyma leading to extensive cyst substitution in ADPKD (D). At histological examination, irregularly shaped biliary structures (microhamartomas) surrounded by an extensive deposition of fibrotic tissue, are present in the portal tracts in ARPKD (B, H&E, M: 100x), while in ADPKD, biliary cysts appear as large, circular biliary structures, lined by cuboidal or flattened epithelium, with negligible amount of peribiliary fibrosis (E, H&E, M: 100x). The pathogenetic mechanism underlying cyst formation is characterised by progressive segmental dilation of biliary structures which maintain their connection to the biliary tree in ARPKD (C), whereas biliary cysts detach from the bile duct and then progressively increase in size in ADPKD (F). Alternatively, based on previous histopathological studies112–114, liver cysts in ADPKD may also derive from dilatation of components of von Meyenburg complexes.

Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD), Congenital Hepatic Fibrosis (CHF) and Caroli’s Disease (CD)

The presence of ductal plate remnants, Von Meyenburg complexes, and biliary cysts variably associated with an intense peribiliary fibrosis, are the main features of fibropolycystic diseases6. These include ARPKD, and its hepatic variants, CHF and CD, and a variety of congenital syndromes (Meckel and Joubert syndromes), which are often embryonically lethal. In CHF and CD, biliary malformations are associated with progressive portal fibrosis leading to portal hypertension, without progressing to frank cirrhosis. In patients with CD, the risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma is substantially increased (about 10%).

CHF and CD are caused by mutations in PKHD1, a gene encoding for fibrocystin (FPC). FPC is a large membrane, receptor-like protein expressed by the basal body of cilia, subcellular organelles that sense the direction of ductal bile flow, and by centromeres of renal tubular and bile duct epithelial cells90–92. Although FPC functions are largely unknown, some of its properties have been recently outlined93. FPC is thought to be involved in a variety of functions, from proliferation to secretion, terminal differentiation, tubulogenesis, and interactions with the extracellular matrix. Silencing Pkhd1 in cultured mouse renal tubular cells altered cytoskeletal organisation and impaired cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts94. Recent evidences indicate that FPC is also involved in planar cell polarity. In the Pck rat, a model orthologue of ARPKD, FPC deficiency is strongly correlated with the loss of PCP at the renal level. This leads to a perturbed mitotic alignment on circumferential tubular cell number expansion, which is ultimately responsible for renal tubular enlargement and cyst formation16. The mechanistic relationships between biliary dysgenesis and portal fibrosis are not understood and this is an area of current investigation.

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) and Polycystic Liver Disease (PLD) are inherited with an autosomal dominant transmission. These conditions do not cause significant liver fibrosis, but rather an enormous increase in liver mass. The formation and progressive enlargement of multiple cysts scattered throughout the liver parenchyma characterises both ADPKD and PLD95. Despite extensive cyst substitution of the hepatic parenchyma, liver function is generally well preserved and portal hypertension is rare. The patients are usually asymptomatic, unless acute and chronic complications (including cyst infections or bleeding and mass effect) develop. ADPKD is caused by mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 genes96,97. The transcribed products of these two genes, polycystin-1 (PC1) and polycystin-2 (PC2), are membrane proteins located in the renal tubular and biliary epithelia. PC1 and PC2 regulate signaling pathways that are involved in epithelial cell morphogenesis, differentiation and proliferation. In conditional, liver specific mice defective for PC-1 or PC-2, polycystic liver disease develops even if PC1 and PC2 are deleted after birth, indicating that PC expression maintain a fundamental morphogenetic role also during adult life27,98. Thus, altered PC function may cause a lack of differentiating signals favouring the maintenance of an immature and proliferative phenotype by biliary epithelial cells ultimately responsible for cyst formation. In fact, cholangiocytes lining the liver cysts present strong phenotypic and functional similarities with ductal plate/reactive ductules26. Among them are an aberrant secretion of several cytokines and chemokines, including IL-699, IL-899, and CXCR2100, a marked over-expression of oestrogen receptors, IGF1, the IGF1 and growth hormone receptors as well as VEGF and its cognate receptor, VEGFR-226. In particular, VEGF potently stimulates the progression of liver cysts in ADPKD via autocrine stimulation of cholangiocyte proliferation and paracrine promotion of pericystic angiogenesis. We have shown that in cystic cholangiocytes from Pkd2-defective mice a MEK/ERK1/2/mTOR pathway is overactive and is responsible for increased hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-dependent VEGF production and increased VEGFR-2-mediated autocrine stimulation of cyst growth. This mechanism represents a potential target for therapy, as the blockade of angiogenic signaling using a competitive inhibitor of VEGFR-2, or the administration of mTOR inhibitors blocks the growth of liver cysts in Pkd2KO mice, and reduces the proliferative activity of the cystic epithelium98. Overall, these data indicate that polycystic liver diseases should be considered as congenital diseases of cholangiocyte signaling101. Phenotypic changes in cyst cholangiocytes with functional relevance for cyst formation and progression are summarised in Table 2. Each pathway is also therapeutically relevant as a potential target amenable of pharmacological interference aimed at reducing disease progression. Future studies will clarify if the use of agents interfering with VEGF or mTOR signaling can be clinically useful and if their use can be extended to other cholangiopathies27.

Table 2.

Phenotypic Changes in Cyst Cholangiocytes

|

In PLD, genetic defects do not involve ciliary proteins. PLD is caused by mutations in PRKCSH, a gene encoding for protein kinase C substrate 80K-H also called hepatocystin102, or in the SEC63 gene103. SEC63 encodes for a component of the molecular machinery regulating translocation and folding of newly synthesised membrane glycoproteins. Hepatocystin and SEC63 are expressed on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)104, and defects in other enzymatic activities associated with the ER, such as xylosyl transferase 2 responsible for initiating heparin sulphate and chondroitin sulphate biosynthesis, have been linked to the development of renal and liver cysts105. PLD serves to highlight the important concept that cystic liver disease does not necessarily derive from ciliary dysfunction, but that the defective proteins are expressed in multiple cellular locations, including the ER.

Alagille syndrome (AGS) is a complex, multisystemic disorder inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and characterised by ductopenia. AGS exhibits a wide range of extrahepatic manifestations (cardiac, vascular, skeletal, ocular, facial, renal, central nervous system), hence the term of “syndromic bile duct paucity”106,107. The hepatic phenotype is recognised by variable degrees of cholestasis, jaundice and pruritus. Fibrosis is not a prominent feature of AGS and frank evolution to cirrhosis is rare, however rare cases lead to liver transplantation108. In nearly 80% of AGS patients, a mutation in the genes JAGGED1109,110, or less frequently, NOTCH2 can be identified111. AGS differs from other cholestatic cholangiopathies in the extent and severity of ductular reaction. The near absence of HPC and RDC in AGS (see Figure 5) is conversely coupled with an extensive accumulation of IHBC. IHBC do not express the biliary specific transcription factor HNF1β, whose expression is controlled by Notch signaling79. This imbalance in the cellular elements of the “hepatic reparative complex”, which is a peculiar histopathological feature of AGS, supports the concept that Notch signaling plays an essential role in liver repair by regulating the generation of biliary committed precursors as well as the branching tubularisation80.

Conclusions

Several cholangiopathies are caused by a malfunction of developmental mechanisms. In these diseases, cholangiocyte dysfunction is often caused by a specific genetic defect relevant to morphogenesis. Also, cholangiocytes express a range of phenotypic features reminiscent of foetal behaviour. In different forms of acquired liver damage, liver repair exploits several developmental mechanisms, in a sort of “recapitulation of ontogenesis”. Ductular reactive cells generated in response to liver damage express several of the autocrine and paracrine signals transitorily expressed by ductal plate cells during liver development. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating development of the biliary tree may help to solve several challenging issues facing modern Hepatology. These may range from the search of novel treatments for patients with biliary diseases, to the need of limit/prevent pathologic repair in chronic liver diseases, to the design of bioartificial liver support devices, to strategies for liver regenerative medicine.

Key Points.

Intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts have different embryologic origins. Whereas cholangiocytes lining the intrahepatic bile ducts derive from hepatoblasts, extrahepatic cholangiocytes derive from the caudal part of the ventral foregut endoderm.

Signals from the portal mesenchyma stimulate hepatoblasts to differentiate into ductal plate cells. After ductal plate duplication, biliary tubule formation requires a process of transient asymmetry that proceeds from the hilum to the periphery of the liver and is completed only after birth. A number of transcription factors and signaling mechanisms have been identified. Notch signaling is involved in multiple steps, from ductal plate formation to ductal plate remodeling and tubularisation.

Ductal plate malformations are caused by genetic defects in proteins expressed in multiple cellular locations, including primary cilia and the endoplasmic reticulum. Phenotypic features reminiscent of ductal plate cells are also expressed by cholangiocytes layering liver cysts and microhamartomas in developmental cholangiopathies. Cholangiopathies are a group of diseases in which cholangiocyte dysfunction is often induced by a specific genetic defect relevant to morphogenesis.

Ductular reaction is a common compensatory and reparative response to different forms of liver damage, which recapitulates ontogenesis. In fact, ductal plates transitorily express several of the autocrine and paracrine signals generated by ductular reactive cells in response to liver damage, during liver development.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating development of the biliary tree in embryonic life provide invaluable clues on the mechanisms underlying epithelial reaction and liver damage in adulthood.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Supported by NIH DK079005, Yale University Liver Center (NIH DK34989) and by a grant from “PSC partners for a care” to MS. Supported by Telethon (GGP09189), Associazione Scientifica Gastroenterologica di Treviso (ASGET, “associazione di promozione sociale senza scopo di lucro”) and by Progetto di Ricerca Ateneo 2008 (CPDA083217) to LF.

The authors wish to thank Massimiliano Cadamuro, Ph.D (Department of Surgical and Gastroenterological Sciences, University of Padua) for the micrographs of histology and assistance in the preparation of the graphics in the manuscript, and Dr. Roberto Agazzi, MD (Department of Radiology, Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo) for providing the radiological images of Caroli’s disease and polycystic liver.

Abbreviations

- GW

week of gestation

- Sox9

SRY-related HMG box transcription factor 9

- K

cytokeratin

- HNF

hepatocyte nuclear factor

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TβRII

transforming growth factor receptor type II

- PCP

planar cell polarity

- IL

interleukin

- Hh

Hedgehog

- Shh

sonic Hedgehog

- DPM

ductal plate malformations

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- PBP

peribiliary plexus

- RBP-JK

recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J

- AGS

Alagille syndrome

- Dvl

Dishevelled

- IGF1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor 1

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor-α

- NCAM

neural cell adhesion molecule

- HPC

hepatic progenitor cells

- IHBC

intermediate hepato-biliary cells

- RDC

reactive ductular cells

- MKS

Meckel syndrome

- ARPKD

autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease

- CHF

congenital hepatic fibrosis

- CD

Caroli’s disease

- FPC

fibrocystin

- ADPKD

autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

- PLD

polycystic liver disease

- PC

polycystin

- PKA

Protein Kinase A

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have potential financial conflicts of interest related to this paper

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lemaigre FP. Mechanisms of liver development: concepts for understanding liver disorders and design of novel therapies. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:62–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raynaud P, Carpentier R, Antoniou A, Lemaigre FP. Biliary differentiation and bile duct morphogenesis in development and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazaridis KN, Strazzabosco M, Larusso NF. The cholangiopathies: disorders of biliary epithelia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1565–1577. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strazzabosco M, Fabris L, Spirli C. Pathophysiology of cholangiopathies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S90–S102. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155549.29643.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desmet VJ. Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variations on the theme “ductal plate malformation”. Hepatology. 1992;16:1069–1083. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desmet VJ. Ludwig symposium on biliary disorders--part I. Pathogenesis of ductal plate abnormalities. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:80–89. doi: 10.4065/73.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roskams T, Desmet V. Embryology of extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts, the ductal plate. Anat Rec. 2008;291:628–635. doi: 10.1002/ar.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan J, Hytiroglou P, Wieczorek R, Park YN, Thung SN, Arias B, et al. Immunohistochemical evidence for hepatic progenitor cells in liver diseases. Liver. 2002;22:365–373. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.01622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Eyken P, Sciot R, Callea F, Van der Steen K, Moerman P, Desmet VJ. The development of the intrahepatic bile ducts in man: a keratin-immunohistochemical study. Hepatology. 1988;8:1586–1595. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakanuma Y, Hoso M, Sanzen T, Sasaki M. Microstructure and development of the normal and pathologic biliary tract in humans, including blood supply. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:552–570. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970915)38:6<552::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libbrecht L, Cassiman D, Desmet V, Roskams T. Expression of neural cell adhesion molecule in human liver development and in congenital and acquired liver diseases. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116:233–239. doi: 10.1007/s004180100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Libbrecht L, Raynaud P, Spirlì C, Fiorotto R, Okolicsanyi L, Lemaigre FP, Strazzabosco M, Roskams T. Angiogenic growth factors secreted by liver epithelial cells modulate arterial vasculogenesis during human liver development. Hepatology. 2008;47:719–728. doi: 10.1002/hep.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpentier R, Suñer RE, Van Hul N, Kopp JL, Beaudry JB, Cordi S, et al. Embryonic ductal plate cells give rise to cholangiocytes, periportal hepatocytes and adult liver progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.049. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuyama K, Kawaguchi Y, Akiyama H, Horiguchi M, Kodama S, Kuhara T, et al. Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nat Genet. 2011;43:34–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoniou A, Raynaud P, Cordi S, Zong Y, Tronche F, Stanger BZ, et al. Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2325–2333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, et al. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z, White P, Tuteja G, Rubins N, Sackett S, Kaestner KH. Foxa1 and Foxa2 regulate bile duct development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1537–1545. doi: 10.1172/JCI38201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zong Y, Panikkar A, Xu J, Antoniou A, Raynaud P, Lemaigre F, et al. Notch signaling controls liver development by regulating biliary differentiation. Development. 2009;136:1727–1739. doi: 10.1242/dev.029140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda A, Kawaguchi Y, Furuyama K, Kodama S, Kuhara T, Horiguchi M, et al. Loss of the major duodenal papilla results in brown pigment biliary stone formation in pdx1 null mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:855–867. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clotman F, Lannoy VJ, Reber M, Cereghini S, Cassiman D, Jacquemin P, et al. The onecut transcription factor HNF6 is required for normal development of the biliary tract. Development. 2002;129:1819–1828. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coffinier C, Gresh L, Fiette L, Tronche F, Schutz G, Babinet C, et al. Bile system morphogenesis defects and liver dysfunction upon targeted deletion of HNF1β. Development. 2002;129:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalinichenko VV, Zhou Y, Bhattacharyya D, Kim W, Shin B, Bambal K, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the mouse Forkhead Box f1 gene causes defects in gall bladder development. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12369–12374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaudio E, Pannarale L, Franchitto A, Onori P, Marinozzi G. Hepatic microcirculation as a morpho-functional basis for the metabolic zonation in normal and pathological rat liver. Ital J Anat Embryol. 1995;100:419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaudio E, Onori P, Franchitto A, Pannarale L, Alpini G, Alvaro D. Hepatic microcirculation and cholangiocyte physiopathology. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2005;110:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaudio E, Franchitto A, Pannarale L, Carpino G, Alpini G, Francis H, et al. Cholangiocytes and blood supply. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3546–3552. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i22.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Fiorotto R, Roskams T, Spirlì C, Melero S, et al. Effects of angiogenic factor overexpression by human and rodent cholangiocytes in polycystic liver diseases. Hepatology. 2006;43:1001–1012. doi: 10.1002/hep.21143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spirli C, Okolicsanyi S, Fiorotto R, Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Lecchi S, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent liver cyst growth in polycystin-2-defective mice. Hepatology. 2010;51:1778–1788. doi: 10.1002/hep.23511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deltenre P, Valla DC. Ischemic cholangiopathy. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:235–246. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masyuk TV, Ritman EL, LaRusso NF. Hepatic artery and portal vein remodeling in rat liver: vascular response to selective cholangiocyte proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63913-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clotman F, Libbrecht L, Gresh L, Yaniv M, Roskams T, Rousseau GG, et al. Hepatic artery malformations associated with a primary defect in intrahepatic bile duct development. J Hepatol. 2003;39:686–692. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemaigre F, Zaret KS. Liver development update. New embryo models, cell lineage control, and morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, White P, Tuteja G, Rubins N, Sackett S, Kaestner KH. Foxa1 and Foxa2 regulate bile duct development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1537–1545. doi: 10.1172/JCI38201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bossard P, Zaret KS. GATA transcription factors as potentiators of gut endoderm differentiation. Development. 1998;125:4909–4917. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rojas A, De Val S, Heidt AB, Xu SM, Bristow J, Black BL. Gata4 expression in lateral mesoderm is downstream of BMP4 and is activated directly by Forkhead and GATA transcription factors through a distal enhancer element. Development. 2005;132:3405–3417. doi: 10.1242/dev.01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haworth KE, Kotecha S, Mohun TJ, Latinkic BV. GATA4 and GATA5 are essential for heart and liver development in Xenopus embryos. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi JM, Dunn NR, Hogan BL, Zaret KS. Distinct mesodermal signals, including BMPs from the septum transversum mesenchyme, are required in combination for hepatogenesis from the endoderm. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1998–2009. doi: 10.1101/gad.904601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clotman F, Lemaigre FP. Control of hepatic differentiation by activin/TGFbeta signaling. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:168–171. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.2.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Igarashi P, Shao X, McNally BT, Hiesberger T. Roles of HNF-1beta in kidney development and congenital cystic diseases. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1944–1947. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raynaud P, Tate J, Callens C, Cordi S, Vandersmissen P, Carpentier R, et al. A classification of ductal plate malformations based on distinct pathogenic mechanisms of biliary dysmorphogenesis. Hepatology. 2011;53:1959–1966. doi: 10.1002/hep.24292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorent K, Yeo SY, Oda T, Chandrasekharappa S, Chitnis A, Matthews RP, et al. Inhibition of Jagged-mediated Notch signaling disrupts zebrafish biliary development and generates multi-organ defects compatible with an Alagille syndrome phenocopy. Development. 2004;131:5753–5766. doi: 10.1242/dev.01411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lozier J, McCright B, Gridley T. Notch signaling regulates bile duct morphogenesis in mice. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornell RA, Eisen JS. Notch in the pathway: the roles of Notch signaling in neural crest development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tchorz JS, Kinter J, Müller M, Tornillo L, Heim MH, Bettler B. Notch2 signaling promotes biliary epithelial cell fate specification and tubulogenesis during bile duct development in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:871–879. doi: 10.1002/hep.23048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Guido M, Spirli C, Fiorotto R, Colledan M, et al. Analysis of liver repair mechanisms in Alagille syndrome and biliary atresia reveals a role for notch signaling. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:641–653. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hofmann JJ, Zovein AC, Koh H, Radtke F, Weinmaster G, Iruela-Arispe ML. Jagged1 in the portal vein mesenchyme regulates intrahepatic bile duct development: insights into Alagille syndrome. Development. 2010;137:4061–4072. doi: 10.1242/dev.052118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loomes KM, Russo P, Ryan M, Nelson A, Underkoffler L, Glover C, et al. Bile duct proliferation in liver-specific Jag1 conditional knockout mice: effects of gene dosage. Hepatology. 2007;45:323–330. doi: 10.1002/hep.21460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sparks EE, Huppert KA, Brown MA, Washington MK, Huppert SS. Notch signaling regulates formation of the three-dimensional architecture of intrahepatic bile ducts in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51:1391–1400. doi: 10.1002/hep.23431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan X, Yuan Y, Zeng G, Apte U, Thompson MD, Cieply B, et al. Beta-catenin deletion in hepatoblasts disrupts hepatic morphogenesis and survival during mouse development. Hepatology. 2008;47:1667–1679. doi: 10.1002/hep.22225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montcouquiol M, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Kelley MW. Noncanonical Wnt signaling and neural polarity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:363–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Krönig C, et al. Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2005;37:537–543. doi: 10.1038/ng1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirose Y, Itoh T, Miyajima A. Hedgehog signal activation coordinates proliferation and differentiation of fetal liver progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:2648–2657. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alvaro D, Alpini G, Onori P, Perego L, Svegliati Baroni G, Franchitto A, et al. Estrogens stimulate proliferation of intrahepatic biliary epithelium in rats. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1681–1691. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alvaro D, Macarri G, Mancino MG, Marzioni M, Bragazzi M, Onori P, et al. Serum and biliary insulin-like growth factor I and vascular endothelial growth factor in determining the cause of obstructive cholestasis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:451–459. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Onori P, Alvaro D, Floreani AR, Mancino MG, Franchitto A, Guido M, et al. Activation of the IGF1 system characterizes cholangiocyte survival during progression of primary biliary cirrhosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:327–334. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6R7125.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park J, Gores GJ, Patel T. Lipopolysaccharide induces cholangiocyte proliferation via an interleukin-6-mediated activation of p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Hepatology. 1999;29:1037–1043. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fabris L, Strazzabosco M, Crosby HA, Ballardini G, Hubscher SG, Kelly DA, et al. Characterization and isolation of ductular cells coexpressing neural cell adhesion molecule and Bcl-2 from primary cholangiopathies and ductal plate malformations. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1599–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sell S. Is there a liver stem cell? Cancer Res. 1990;50:3811–3815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sell S. Liver stem cells. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crosby HA, Hubscher S, Fabris L, Joplin R, Sell S, Kelly D, et al. Immunolocalization of putative human liver progenitor cells in livers from patients with end-stage primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis using the monoclonal antibody OV-6. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:771–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roskams T, Theise ND, Balabaud C, Bhagat G, Bhathal PS, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Nomenclature of the finer branches of the biliary tree: canals, ductules, and ductular reactions in human livers. Hepatology. 2004;39:1739–1745. doi: 10.1002/hep.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fausto N, Campbell JS, Riehle KJ. Liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2006;43:S45–S53. doi: 10.1002/hep.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strazzabosco M, Spirli C, Okolicsanyi L. Pathophysiology of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:244–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dünker N, Krieglstein K. Tgfbeta2 −/− Tgfbeta3 −/− double knockout mice display severe midline fusion defects and early embryonic lethality. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2002;206:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s00429-002-0273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Surveyor GA, Brigstock DR. Immunohistochemical localization of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in the mouse embryo between days 7.5 and 14. 5 of gestation. Growth Factors. 1999;17:115–124. doi: 10.3109/08977199909103520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coulomb-L’Hermin A, Amara A, Schiff C, Durand-Gasselin I, Foussat A, Delaunay T, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and antenatal human B cell lymphopoiesis: expression of SDF-1 by mesothelial cells and biliary ductal plate epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8585–8590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jia C. Advances in the regulation of liver regeneration. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5:105–121. doi: 10.1586/egh.10.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.LeSagE G, Alvaro D, Benedetti A, Glaser S, Marucci L, Baiocchi L, et al. Cholinergic system modulates growth, apoptosis, and secretion of cholangiocytes from bile duct-ligated rats. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marzioni M, Glaser S, Francis H, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Alvaro D, et al. Autocrine/paracrine regulation of the growth of the biliary tree by the neuroendocrine hormone serotonin. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:121–137. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gigliozzi A, Alpini G, Baroni GS, Marucci L, Metalli VD, Glaser SS, et al. Nerve growth factor modulates the proliferative capacity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium in experimental cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1198–1209. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yasoshima M, Kono N, Sugawara H, Katayanagi K, Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Increased expression of interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in pathologic biliary epithelial cells: in situ and culture study. Lab Invest. 1998;78:89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jakubowski A, Ambrose C, Parr M, Lincecum JM, Wang MZ, Zheng TS, et al. TWEAK induces liver progenitor cell proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2330–2340. doi: 10.1172/JCI23486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Napoli J, Prentice D, Niinami C, Bishop GA, Desmond P, McCaughan GW. Sequential increases in the intrahepatic expression of epidermal growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta in a bile duct ligated rat model of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1997;26:624–633. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gouw AS, van den Heuvel MC, Boot M, Slooff MJ, Poppema S, de Jong KP. Dynamics of the vascular profile of the finer branches of the biliary tree in normal and diseased human livers. J Hepatol. 2006;45:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Omenetti A, Diehl AM. The adventures of sonic hedgehog in development and repair. II. Sonic hedgehog and liver development, inflammation, and cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G595–G598. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00543.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sackett SD, Gao Y, Shin S, Esterson YB, Tsingalia A, Hurtt RS, et al. Foxl1 promotes liver repair following cholestatic injury in mice. Lab Invest. 2009;89:1387–1396. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fabris L, Strazzabosco M. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in biliary diseases. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:11–32. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spee B, Carpino G, Schotanus BA, Katoonizadeh A, Vander Borght S, Gaudio E, et al. Characterisation of the liver progenitor cell niche in liver diseases: potential involvement of Wnt and Notch signalling. Gut. 2010;59:247–257. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.188367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Apte U, Thompson MD, Cui S, Liu B, Cieply B, Monga SP. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling mediates oval cell response in rodents. Hepatology. 2008;47:288–295. doi: 10.1002/hep.21973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Guido M, Spirli C, Fiorotto R, Colledan M, et al. Analysis of liver repair mechanisms in Alagille syndrome and biliary atresia reveals a role for notch signaling. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:641–653. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fiorotto R, Spirli C, Scirpo R, Fabris L, Huppert S, Torsello B, et al. Defective progenitor cells activation and biliary tubule formation in liver conditional RBP-jk-knock out mice exposed to cholestatic injuries reveals a key role for Notch signaling in liver repair. Hepatology. 2010;52:406A. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weatherbee SD, Niswander LA, Anderson KV. A mouse model for Meckel syndrome reveals Mks1 is required for ciliogenesis and Hedgehog signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4565–4575. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi SS, Omenetti A, Syn WK, Diehl AM. The role of Hedgehog signaling in fibrogenic liver repair. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Omenetti A, Bass LM, Anders RA, Clemente MG, Francis H, Guy CD, et al. Hedgehog activity, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions, and biliary dysmorphogenesis in biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2011;53:1246–1258. doi: 10.1002/hep.24156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jørgensen MJ. The ductal plate malformation. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl. 1977;257:1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Redston MS, Wanless IR. The hepatic von Meyenburg complex: prevalence and association with hepatic and renal cysts among 2843 autopsies. Mod Pathol. 1996;9:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tsui WM. How many types of biliary hamartomas and adenomas are there? Adv Anat Pathol. 1998;5:16–20. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jain D, Sarode VR, Abdul-Karim FW, Homer R, Robert ME. Evidence for the neoplastic transformation of Von Meyenburg complexes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1131–1139. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200008000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Song JS, Lee YJ, Kim KW, Huh J, Jang SJ, Yu E. Cholangiocarcinoma arising in Von Meyenburg complexes: report of four cases. Pathol Int. 2008;58:503–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu AM, Xian ZH, Zhang SH, Chen XF. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma arising in multiple bile duct hamartomas: report of two cases and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:580–584. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282fc73b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ward CJ, Hogan MC, Rossetti S, Walker D, Sneddon T, Wang X, et al. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat Genet. 2002;30:259–269. doi: 10.1038/ng833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang MZ, Mai W, Li C, Cho SY, Hao C, Moeckel G, et al. PKHD1 protein encoded by the gene for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease associates with basal bodies and primary cilia in renal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2311–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harris PC, Torres VE. Polycystic kidney disease. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:321–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.101707.125712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Banales JM, Masyuk TV, Gradilone SA, Masyuk AI, Medina JF, LaRusso NF. The cAMP effectors Epac and protein kinase a (PKA) are involved in the hepatic cystogenesis of an animal model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) Hepatology. 2009;49:160–174. doi: 10.1002/hep.22636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mai W, Chen D, Ding T, Kim I, Park S, Cho SY, et al. Inhibition of Pkhd1 impairs tubulomorphogenesis of cultured IMCD cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4398–4409. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tahvanainen E, Tahvanainen P, Kääriäinen H, Höckerstedt K. Polycystic liver and kidney diseases. Ann Med. 2005;37:546–555. doi: 10.1080/07853890500389181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Igarashi P, Somlo S. Genetics and pathogenesis of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2384–2398. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000028643.17901.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wilson PD. Polycystic kidney disease: new understanding in the pathogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1868–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Spirli C, Okolicsanyi S, Fiorotto R, Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Lecchi S, et al. ERK1/2-dependent vascular endothelial growth factor signaling sustains cyst growth in polycystin-2 defective mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:360–371. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nichols MT, Gidey E, Matzakos T, Dahl R, Stiegmann G, Shah RJ, et al. Secretion of cytokines and growth factors into autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease liver cyst fluid. Hepatology. 2004;40:836–846. doi: 10.1002/hep.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Amura CR, Brodsky KS, Gitomer B, McFann K, Lazennec G, Nichols MT, et al. CXCR2 agonists in ADPKD liver cyst fluids promote cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C786–C796. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00457.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Strazzabosco M, Somlo S. Polycystic liver diseases: congenital disorders of cholangiocyte signaling. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1855–1859. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Drenth JP, te Morsche RH, Smink R, Bonifacino JS, Jansen JB. Germline mutations in PRKCSH are associated with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Davila S, Furu L, Gharavi AG, Tian X, Onoe T, Qian Q, et al. Mutations in SEC63 cause autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:575–577. doi: 10.1038/ng1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Janssen MJ, Waanders E, Woudenberg J, Lefeber DJ, Drenth JP. Congenital disorders of glycosylation in hepatology: the example of polycystic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2010;52:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Condac E, Silasi-Mansat R, Kosanke S, Schoeb T, Towner R, Lupu F, et al. Polycystic disease caused by deficiency in xylosyltransferase 2, an initiating enzyme of glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9416–9421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700908104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Krantz ID, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. Clinical and molecular genetics of Alagille syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11:558–564. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199912000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. Alagille syndrome and the Jagged1 gene. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:525–534. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Emerick KM, Rand EB, Goldmuntz E, Krantz ID, Spinner NB, Piccoli DA. Features of Alagille syndrome in 92 patients: frequency and relation to prognosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:822–829. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oda T, Elkahloun AG, Pike BL, Okajima K, Krantz ID, Genin A, Piccoli DA, Meltzer PS, Spinner NB, Collins FS, Chandrasekharappa SC. Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:235–242. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li L, Krantz ID, Deng Y, Genin A, Banta AB, Collins CC, et al. Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat Genet. 1997;16:243–251. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McDaniell R, Warthen DM, Sanchez-Lara PA, Pai A, Krantz ID, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:169–173. doi: 10.1086/505332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Karhunen PJ. Adult polycystic liver disease and biliary microhamartomas (von Meyenburg’s complexes) Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A. 1986;94:397–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb03011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Grimm PC, Crocker JF, Malatjalian DA, Ogborn MR. The microanatomy of the intrahepatic bile duct in polycystic disease: comparison of the cpk mouse and human. J Exp Pathol. 1990;71:119–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ramos A, Torres VE, Holley KE, Offord KP, Rakela J, Ludwig J. The liver in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Implications for pathogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]