Abstract

Background/Aims

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has a poor survival rate due to recurrent intrahepatic metastases and lack of effective adjuvant therapy. Aspartate-β-hydroxylase (ASPH) is an attractive cellular target since it is a highly conserved transmembrane protein overexpressed on both murine and human HCC tumors, and promotes a malignant phenotype as characterized by enhanced tumor cell migration and invasion.

Methods

Dendritic cells (DCs), expanded and isolated from the spleen, were incubated with a cytokine cocktail to optimize IL-12 secretion and co-stimulatory molecule expression, then subsequently loaded with ASPH protein for immunization. Mice were injected with syngeneic BNL HCC tumor cells followed by subcutaneous inoculation with 5–10×105 ASPH loaded DCs using a prophylactic and therapeutic experimental approach. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were characterized, and their role in producing anti-tumor effects determined. The immunogenicity of ASPH protein with respect to activating antigen specific CD4+ T cells derived from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was also explored.

Methods

We found that immunotherapy with ASPH-loaded DCs suppressed and delayed established HCC and tumor growth when administered prophylactically. Ex-vivo re-stimulation experiments and in vivo depletion studies demonstrate that both CD4+ and CD8+ cells contributed to anti-tumor effects. Using PBMCs derived from healthy volunteers and HCC patients, we showed that ASPH stimulation led to significant development of antigen-specific CD4+ T-cells.

Conclusion

Immunization with ASPH-loaded DCs has substantial anti-tumor effects which could reduce the risk of HCC recurrence.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, immunotherapy, dendritic cells, aspartate-β-hydroxylase, CD4+ cells

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer [1] with an increasing incidence noted in the last two decades in the United States, Europe, and Japan. This increased rate is expected to continue over the next 10 – 30 years due to a large pool of individuals chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) virus. It is in the setting of persistent viral infection of the liver that these tumors most commonly arise. The five-year survival rate of patients in the United States is only 9%, [2, 3] and there is a recurrence rate of more than 70% following surgical resection [4]. Therefore new therapeutic approaches are needed [5].

We have studied the regulation, expression, and function of a highly conserved enzyme designated aspartate-β-hydroxylase (ASPH) that has been found to be overexpressed in HBV- and HCV-related HCC as well as murine hepatomas, and which may serve both as a biomarker and therapeutic target for this disease. ASPH is a ~86kD Type 2 transmembrane protein and member of the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family [6]. ASPH catalyzes post-translational hydroxylation of β-carbons of specific aspartate and asparagine residues in epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains in proteins such as Notch, and Jagged, which have known roles in cell growth, differentiation, cellular migration, adhesion, and motility [7–10]. The ASPH gene becomes overexpressed in HCC tumors and the protein translocates to the plasma membrane from the endoplasmic reticulum where it becomes accessible to the extracellular environment and could serve as a tumor associated antigen (TAA) target for immunotherapy.

We employed ASPH-loaded DCs to generate anti-tumor immune responses. DCs are antigen-presenting cells (APCs) with the unique ability to take-up and process antigens. DCs can induce effector CD4+ T helper cell (Th) responses. The Th1 response is characterized by the production of interferon (INF)-gamma (γ) which activates CTLs (CD8+) and induces cell mediated immunity [11]. These T cells are subsequently stimulated and polarized by APC-secreted cytokines such as IL-12 as well as by interaction with TCR co-receptors such as the B7 family of molecules. As a result, antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells may cooperatively eliminate TAA expressing tumors.

Previous investigations have demonstrated the importance of ASPH in the pathogenesis of HCC recurrence and progression via promotion of tumor cell migration and invasion [8, 12–14]. Most if not all HCC cells within a tumor express ASPH on the cell surface [15]. These findings generated a hypothesis that targeting of this overexpressed cell surface molecule by an immunotherapeutic approach may inhibit the development and progression of ASPH-expressing HCC tumors.

Methods

Recombinant human aspartate-β-hydroxylase

The full length human ASPH (GenBank accession no. 583325) was cloned into the EcoRI site of the pcDNA vector (Invitrogen). Recombinant ASPH protein produced in a Baculovirus system (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instruction.

Mice and generation of mature dendritic cells

Female 6 – 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Harlan Laboratories) were used. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rhode Island Hospital. We isolated DCs as previously described [16]. This detailed method is further described in the Supplementary Methods.

Immunization

Mice were immunized by injecting 5 – 10 × 105 DCs or control HBSS into the base of the tail. Unless otherwise specified, mice were immunized twice spaced two-weeks apart. For the in vitro experiments, we studied the immunized mice two weeks after the last immunization. In other experiments, the immunization schedules are specified.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent and in vitro cytotoxicity assays

See Supplementary Methods for details.

Tumor cell culture and inoculation

The BNL 1ME A.7R.1 (BNL) murine HCC cell line was purchased from ATCC BNL and its highly malignant and fast-growing subclone BNLT3 as well as SP2-0 murine myeloma cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS. The highly tumorigenic subclone of BNLT3 cells was generated by three serial subcutaneous passages of parental BNL cells. It is noteworthy that BNLT3 (1 × 103 cells) were capable of forming large subcutaneous tumors in incubated mice whereas 1 × 106 parental BNL cells were required. In these experiments , 1 × 106 BNL or 4 × 103 BNLT3 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank and tumor size was measured every 7 or 3 days, respectively. Mice bearing tumors where the shorter diameter exceeded 10 mm were euthanized according to the requirements of the Animal Welfare Committee of the Rhode Island Hospital.

Evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and in vivo depletion of immune cells

See Supplemental Methods for complete description.

Human studies

The protocol for these experiments was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rhode Island Hospital. Experiments were performed according to the methods published by Moser, et al [17]. Detailed protocols, statistical analysis and HCC patient characteristics are described in the Supplementary Methods (Table 1).

Results

Activation of DCs

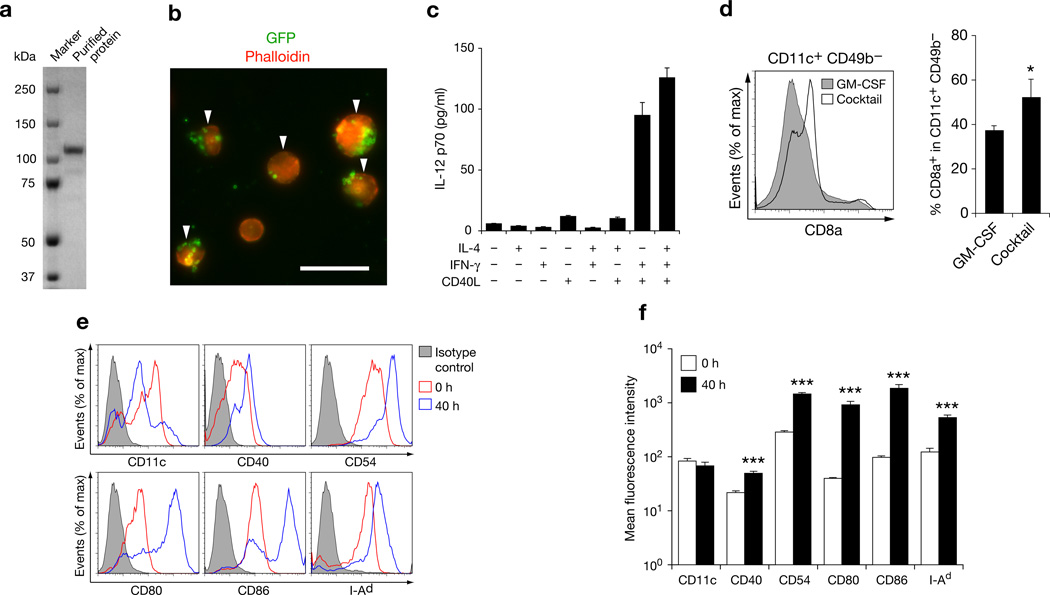

Purified ASPH protein was obtained using a baculovirus expression system to yield a single band on SDS-PAGE which was immunologically confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1a). A previously described method was employed for isolation and purification of murine DCs; this technique combines three critical elements necessary for efficient DC-based immunization including maturation, enrichment and antigen targeting [16]. The percent of isolated DCs ingesting GFP-coated magnetic microbeads was 73.2 ± 4.1% (Fig. 1b). Fetal bovine serum was not used as a component of culture medium to avoid confounding non-specific immune responses [18, 19]. The combination of all four cytokines (IL-4, IFNγ, CD40L and GM-CSF) resulted in a high secretion of IL-12 by DCs (Fig. 1c). The CD8a+ DC subset has potent cross-presentation capabilities necessary for the induction of antitumor immunity [20]; the four cytokine cocktail increased the proportion of this subset in the DC population (Fig. 1d). DC maturation markers including CD40, CD54, CD80, CD86, and I-Ad were significantly upregulated as well (Fig. 1e, f).

Figure 1. Characteristics of DCs used for immunization.

(a) SDS-PAGE of purified recombinant ASPH used to pulse DCs. (b) Fluorescence microscopy demonstrating phagocytosis of GFP-coated microbeads by DCs (arrowheads) . Bar scale 20 µm. (c) IL-12 p70 secretion by DCs in the presence of cytokines; results were derived from triplicate cultures. (d) CD8a+ expression in CD11c+ CD49b− cells derived from DCs cultured with GM-CSF or with GM-CSF, IL-4, IFNγ, and CD40L combinations (left panel). Percent of CD8a+ cells in the CD11c+ CD49b− cell population. Results were derived from three independent experiments (right panel). (e) Flow cytometry of DCs before and after the 40-h culture with the cytokine cocktail demonstrating CD11c and five additional co-stimulatory DC maturation marker expression. (f) Changes in mean fluorescence intensities of DC cell surface marker expression generated from three experiments. All studies except for Western blot analysis were performed at least twice with similar results. Bar graphs are shown as means ± S.D. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Effect of DC immunization on HCC growth in vivo

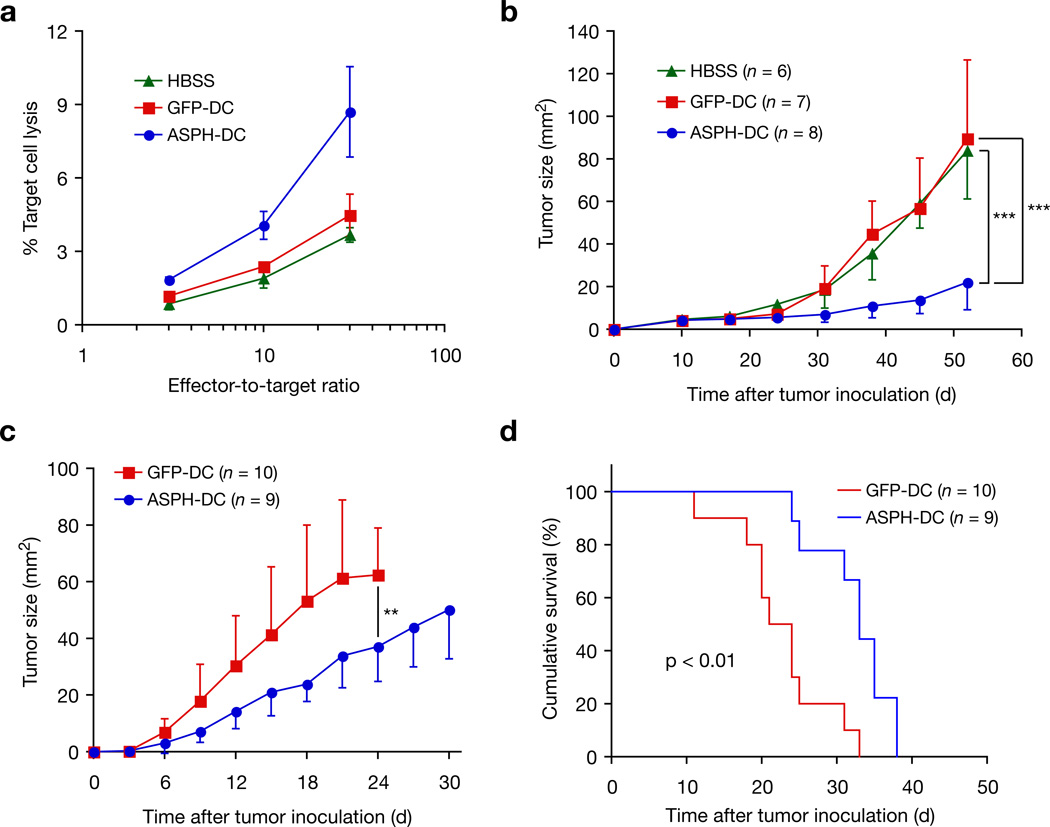

Immunization with ASPH-loaded DCs induced antitumor immunity against the syngeneic BNL 1ME ASPH expressing HCC cell line [21] [Supplementary Fig. 1]. An in vitro cytotoxicity assay was also performed using splenocytes derived from mice immunized with Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS), green fluorescent protein (GFP) or ASPH-loaded DCs to demonstrate ASPH-specific cytotoxicity (Fig. 2a). Similar anti-tumor responses were obtained using a different ASPH-expressing murine SP2-0 myeloma cell line as target cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although the specific CTL activity is low (9%) due principally to reduced MHC class I expression on HCC cells compared SP2-0, the result is highly statistically significant. Irrelevant murine fibroblast target cells demonstrated no lysis. Immunization of mice bearing BNL-derived established tumors with ASPH-loaded DCs significantly suppressed tumor growth compared to immunization with HBSS and GFP-loaded DCs (Fig. 2b). Prophylactic immunization with ASPH-loaded DCs before inoculation of BNLT3 (a rapidly growing and highly malignant subline of BNL) also revealed delayed tumor growth and prolonged survival compared to control mice immunized with GFP-loaded DCs (Fig. 2c, d).

Figure 2. Antitumor immunity induced by immunization with ASPH-loaded DCs.

(a) Results of in vitro cytotoxicity assays against BNL, a syngenic murine HCC cell line. Mean values of target cell lyses were derived from triplicate cultures; three independent experiments were performed with similar findings. (b) Effect of immunization with ASPH-DC on established tumors. After the subcutaneous inoculation of BNL (1 × 106 cells) on day 0, tumors were allowed to progress to about 0.5 cm in size. Tumor-bearing mice were immunized with HBSS, GFP-DC, or ASPH-DC on days 10 and 15 after inoculation of HCC cells. Mean tumor size (area mm2) are shown. Findings were representative of two experiments with similar results. (c) Effect of prophylactic immunization with ASPH-DC on subsequent HCC tumor growth by BNLT3. Mean tumor size (area mm2) is shown. Graph is representative of two experiments with similar results. (d) Kaplan-Meie survival curves of the same experiment shown in (c). Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Generation of cellular immune responses to ASPH

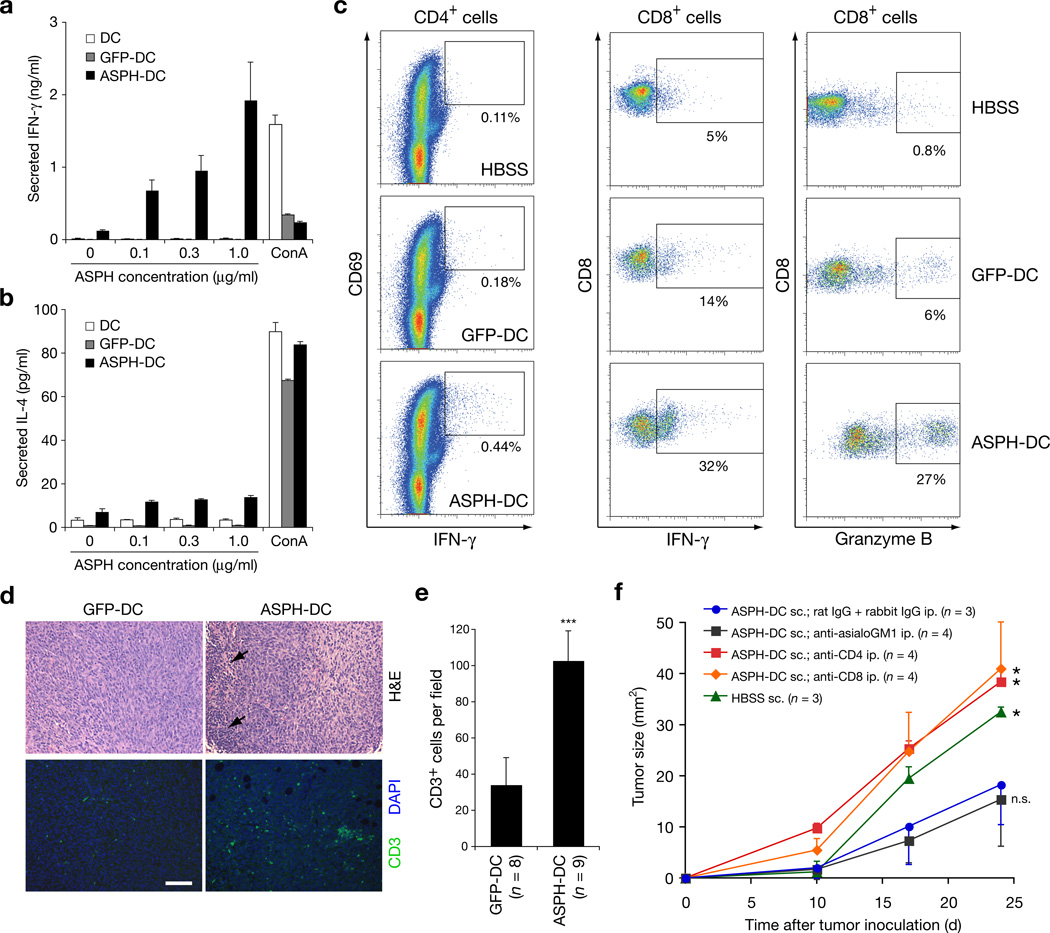

Splenocytes derived from the ASPH-DC immunized mice were restimulated with ASPH protein and exhibited a high level IFNγ secretion as an index of an antigen specific immune response. In contrast, IL-4 secretion by the restimulated splenocytes was far lower in all study groups (Fig. 3a, b). When CD4+ T cells derived from immunized mice were restimulated with ASPH-loaded DCs, it was found that activated CD4+ cells expressing CD69 and IFNγ were generated (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3). When splenocytes derived from mice immunized with ASPH-loaded DCs were restimulated with ASPH protein, IFNγ+ and granzyme Bhi CD8+ cells were found to be increased as well (Fig. 3c). Thus, both antigen specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were generated, and may have contributed to ASPH-mediated anti-tumor immune responses. Staining of BNLT3 tumors (H&E) revealed focal areas of lymphocytic infiltration in tumors derived from mice immunized with ASPH-loaded DCs (Fig. 3d). More important, CD3+ T cells were increased in tumors from mice immunized with ASPH-loaded DCs (Fig. 3 d, e). It was of interest that depletion of either CD4+ or CD8+ T but not NK cells abolished anti-tumor effects generated through immunization with ASPH-loaded DCs (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells mediate antitumor immunity induced by immunization with ASPH-DC.

(a,b) Cytokine production by splenocytes derived from immunized mice in response to ASPH restimulation. Splenocytes derived from mice immunized with DCs only (DC), or GFP-DC, or ASPH-DC were restimulated with 0 – 1 µg/ml ASPH or 10 µg/ml concanavalin A (ConA) as a positive control. Mean concentration of IFNγ (a) and IL-4 (b) produced from triplicate cultures are shown. (c) ASPH-specific activation of CD4+ T cells. Expression of CD69 and IFNγ in CD4+ cells are shown. (d) ASPH-specific activation of CD8+ splenocytes. Expression of IFNγ and granzyme B in CD8+ cells are shown. (d, e) Evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Mice with established tumors were immunized twice with GFP-DC or ASPH-DC. Excised tumors were stained by H&E for histology and anti-CD3 antibody by immunofluoresence (d). Arrows indicate focal infiltration of mononuclear cells. Bar scale for d is 100 µm. (e) Mean level of tumor-infiltrating CD3+ T cells per field. Results were derived from two experiments. ***P < 0.001. (f) Effect of immune cell depletion on tumor growth in mice immunized with ASPH-DC. Mean tumor size derived from each group and evaluated over time (days) is presented. All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results. *P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. All error bars are shown as mean ± S.D.

ASPH-loaded DCs activate CD4+ cells in PBMC’s

These experiments focused on the activation of CD4+ T cells following ASPH stimulation since it has been established that generation of such cells are critical for inhibition of tumor growth [22, 23]. Activated CD4+ T cells express CD154 [24], and we measured CD154 in combination with IFNγ expression as surrogate markers for antigen-specific activation of CD4+ T cells in PBMCs derived from normal controls and patients with HCC [17, 25, 26]. The CD4+ T cells were initially stimulated with autologous ASPH-pulsed DCs. Restimulation of the CD4+ T cells with ASPH-pulsed DCs resulted in a robust increase in the CD154+ cell sub-population compared to restimulation of the same cells with DCs pulsed with another HCC related protein biomarker such as AFP (Fig. 4 a,b). Thus, simultaneous comparisons were made regarding the immunogenicity of ASPH to that of AFP. Unlike ASPH, restimulation of AFP-stimulated CD4+ T cells with AFP-pulsed DCs exhibited a non-significant decrease in the CD154+ population when compared to the control (Fig. 4 a,b). However, stimulation with ASPH but not AFP activated antigen specific CD4+ T cells derived from normal volunteers. More important, the CD4+ T cell subset expressing CD154 and IFNγ was significantly expanded when CD4+ T cells initially stimulated with ASPH-pulsed DCs were then restimulated with the same autologous ASPH-pulsed DCs (Fig. 4 a,b). Similar results were obtained in an experiment using ASPH-pulsed DCs or DCs (only) without antigen loading for restimulation (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, it was also possible to activate CD4+ T cells to ASPH in PBMCs derived from patients with HCC (Fig. 4 c,d). Generation of antigen specific CD4+ cells following ASPH-DC but not AFP-DC immunization suggesting that this cell surface expression protein may have potential as an immunotherapeutic target for such tumors.

Figure 4. Generation of antigen specific CD4+ cells in humans.

CD4+ T cells purified from PBMCs were cocultured with monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) loaded with either recombinant α-fetoprotein (AFP) or ASPH for 8 days (Stimulation). The lymphocytes were then challenged by MoDCs loaded with either AFP or ASPH for 7 h (Recall). (a,c) Examples of the ASPH specific CD154+ population in CD4+ cells derived from healthy volunteers (a,b) and HCC patients (c,d). Analysis of CD154 expression generated by ASPH in PBMCs derived from five healthy volunteers (a,b; right panel) and five patients with HCC (c,d; right panel). The percent of CD154+ cells represented in CD4+ cell populations are shown. Analysis of the CD154+ IFNγ+ subpopulation derived from CD4+ cells of healthy volunteers (b) and HCC patients (d) after stimulation with ASPH-loaded DCs. Summary of CD154 and IFNγ expressing cells represented in PBMCs derived from five healthy human volunteers and five patients with HCC (a,b,c,d; right panels, respectively). The percent of CD154+ IFNγ+ cells are shown. *P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. Note that AFP-loaded DCs were not immunogenic in developing antigen-specific CD4+ cells either in PBMC derived from normal human volunteers, or patients with HCC.

Discussion

Studies suggest that some “HCC associated antigens” including the cancer testis antigens (CT-antigens) are immunogenic and potential targets for vaccine development [27–32]. However subsequent host immune responses following vaccination have generally failed to control tumor growth. Inducible cellular immunity against α-fetoprotein, glypican-3, mutant p53, and proteins derived from HBV and HCV have been demonstrated in humans as well as in murine models [33–36]. Clinical investigation reveals improved survival when patients were immunized with tumor or formalin-fixed HCC tissue lysates [37, 38]. HCC tumor vaccine studies have been generally disappointing, and this lack of success may depend, in part on the characteristics of the immunizing antigen, as well as the type and robustness of the subsequent host cellular immune response.

We have identified ASPH as a potential candidate protein for immunotherapy of HCC. There are several attractive features of this target expressed on the surface of HCC cells. First, it is a transmembrane protein overexpressed in 70–90% of human tumors and all 7 HCC cells lines tested thus far [8, 12]. Second, ASPH is not expressed, or is expressed at very low levels in normal tissues [8, 12, 15, 39]. Third, functional analysis of ASPH reveals that it promotes HCC cell migration and invasion which may lead to tumor progression [12, 40, 41]. Fourth, clinicopathologic studies suggest that ASPH expression correlates with poorly-differentiated HCC tumors with intrahepatic metastasis which is a leading cause of post-surgical recurrence and reduced patient survival [14, 41].

In developing an immunotherapeutic strategy, DCs must be activated before they are capable of inducing anti-tumor immunity. As shown here, activated DCs have improved ASPH presenting abilities due to enhanced expression of T cell activating co-stimulatory molecules. Other observations suggest that it may be necessary to employ microbial products such as CpG motifs as adjuvants [42, 43] as well as cytokine additions such as IL-2 [44]. In addition, blocking cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) may be necessary to achieve optimal cellular immune responses to TAAs [45, 46]. Blocking of CTLA-4 expression has resulted in the unmasking of TAA-specific immune responses by changing cytokine and chemokine profiles exhibited by mononuclear cells stimulated with TAA-related peptides in patients with HCC [47].

In the present investigation it was first determined if immunotherapy with ASPH-loaded DCs induces antitumor immunity against HCC grown in mice (Figs. 1–3). It should be noted that the syngeneic BNLT3 cells used in the tumor prevention model (Fig. 2 c,d) were from a highly malignant, rapidly-growing sub-line that formed subcutaneous tumors in 100% of mice after inoculation of only 1 × 103 HCC cells. In contrast, in the treatment of established tumor models (Fig 3b) the BNL 1 ME A.7R.1 cells required 1 × 106 cells to establish slow-growing subcutaneous tumors in 100% of animals. Thus, the anti-tumor effects of immunotherapy with ASPH-loaded DCs was most striking with the BNL syngeneic HCC cell line.

Our findings indicate that ASPH may be a highly effective target protein for DC-based immunotherapy of HCC. Previous studies indicate that overexpression of ASPH increases cell motility and invasiveness of HCC and cholangiocarcinoma tumor cells [12,13] whereas gene knockdown strikingly reduces this phenotype. These findings have been complemented by a large-scale human study reporting that high level ASPH expression in HCC tumors was linked to tumor recurrence and poor patient survival following surgical resection [14]. In addition, high ASPH expression was also predictive of intrahepatic metastasis whereas lower levels of protein detection were related to a more differentiated tumor phenotype [14, 41]. These observations suggest that ASPH-DC immunotherapy could potentially delay recurrence of HCC following surgical resection. Antibody mediated therapy may also be useful as an anti-tumor approach since ASPH is a Type II transmembrane protein highly expressed on the cell surface and it accumulates during the transformation process [12]. Indeed, a human anti-ASPH monoclonal antibody has been generated to test this hypothesis [48].

Although cytotoxic CD8+ T cells play a central role in eliciting antitumor immunity, there is accumulating evidence to indicate that generation of antigen specific CD4+ T helper cells are absolutely required to augment the function of CD8+ T cells to maintain a sustained anti-tumor immune response. It has been demonstrated that CD4+ T cells will enhance CTL responses through clonal expansion, functioning as antigen-presenting cells for CTLs, and amplify clonal expansion at the tumor site; all such properties support subsequent humoral and cellular anti-tumor immune responses [49].

It is of interest that both antigen specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were generated and found necessary for anti-tumor activity following ASPH-DC immunization in the syngenic murine HCC model. Moreover, it was found that ASPH was a strong immunogen and primed antigen-specific CD4+ T cells derived from normal human and HCC patients PBMC’s whereas AFP did not (Fig 4 a, b, c, d). The finding of weak immunogenicity for AFP is consistent with the observation that CD4+ T cells specific to AFP have not been detected in HCC patients immunized with this antigen although AFP-specific CD8+ T cells have been identified in some individuals with this disease [27]. Therefore, activation of both antigen specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells may be required to generate optimal immunologic responses to ASPH expressing HCC tumors. This is the initial demonstration that ASPH-DC stimulation can lead to antigen specific CD4+ activation in PBMCs derived from HCC patients (Fig 4 c, d), and suggests that immunotherapy with ASPH-loaded DCs may be a novel approach to delay or prevent HCC recurrence following surgical resection.

In summary, the observations that ASPH-DC immunization, which appears to induce antitumor immunity mediated by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against HCC in preclinical animal models and generates antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in PBMCs derived from HCC patients, suggests that cell surface expressed ASPH may be an excellent therapeutic target. Because of its tissue specificity, association with tumor progression, and potent immunogenicity, this protein may represent an attractive candidate for a DC-based immunotherapeutic approach against HCC.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant CA-123544 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Penny Cloutier-Lyons and Paul Monfils for their technical assistance. We also thank Jan Clark for coordinating the human studies.

Glossary

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ASPH

Aspartate-β-hydroxylase

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- TILs

Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- HBV

hepatitis B

- HCV

hepatitis C

- CTLs

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- TAAs

tumor-associated antigens

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- TCR

T cell receptor

- NK

natural killer cells

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- HBSS

Hank’s buffered salt solution

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Shimoda M, Wands JR. Molecular biology of liver carcinogenesis and hepatitis. In: Blumgart J, editor. Blumgart's Surgery of the Liver. Elsevier; 2011. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia M, Jemal A, Ward EM, Center MM, Hao Y, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hertl M, Cosimi AB. Liver transplantation for malignancy. Oncologist. 2005;10:269–281. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-4-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong Y, Sun RL, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. An analysis of 412 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma at a Western center. Ann Surg. 1999;229:790–799. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00005. discussion 799–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz JD, Schwartz M, Mandeli J, Sung M. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: review of the randomised clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jia S, VanDusen WJ, Diehl RE, Kohl NE, Dixon RA, Elliston KO, et al. cDNA cloning and expression of bovine aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14322–14327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldbrunner RH, Haugland HK, Klein CE, Kerkau S, Roosen K, Tonn JC. ECM dependent and integrin mediated tumor cell migration of human glioma and melanoma cell lines under serum-free conditions. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:3679–3687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavaissiere L, Jia S, Nishiyama M, de la Monte S, Stern AM, Wands JR, et al. Overexpression of human aspartyl(asparaginyl)beta-hydroxylase in hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1313–1323. doi: 10.1172/JCI118918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merzak A, Koochekpour S, Pilkington GJ. Adhesion of human glioma cell lines to fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin and collagen I is modulated by gangliosides in vitro. Cell Adhes Commun. 1995;3:27–43. doi: 10.3109/15419069509081276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker RP, Kenzelmann D, Trzebiatowska A, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Teneurins: transmembrane proteins with fundamental roles in development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada Y, Yonemitsu Y. Dramatic improvement of DC-based immunotherapy against various malignancies. Front Biosci. 17:2233–2242. doi: 10.2741/3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Monte SM, Tamaki S, Cantarini MC, Ince N, Wiedmann M, Carter JJ, et al. Aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase regulates hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness. J Hepatol. 2006;44:971–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maeda T, Sepe P, Lahousse S, Tamaki S, Enjoji M, Wands JR, et al. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides directed against aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase suppress migration of cholangiocarcinoma cells. J Hepatol. 2003;38:615–622. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Liu J, Yan ZL, Li J, Shi LH, Cong WM, et al. Overexpression of aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with worse surgical outcome. Hepatology. 2010;52:164–173. doi: 10.1002/hep.23650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantarini MC, de la Monte SM, Pang M, Tong M, D'Errico A, Trevisani F, et al. Aspartyl-asparagyl beta hydroxylase over-expression in human hepatoma is linked to activation of insulin-like growth factor and notch signaling mechanisms. Hepatology. 2006;44:446–457. doi: 10.1002/hep.21272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gehring S, Gregory SH, Wintermeyer P, San Martin M, Aloman C, Wands JR. Generation and characterization of an immunogenic dendritic cell population. J Immunol Methods. 2008;332:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser JM, Sassano ER, Leistritz del C, Eatrides JM, Phogat S, Koff W, et al. Optimization of a dendritic cell-based assay for the in vitro priming of naive human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol Methods. 2010;353:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toldbod HE, Agger R, Bolund L, Hokland M. Potent influence of bovine serum proteins in experimental dendritic cell-based vaccination protocols. Scand J Immunol. 2003;58:43–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Haan JM, Kraal G, Bevan MJ. Cutting edge: Lipopolysaccharide induces IL-10-producing regulatory CD4+ T cells that suppress the CD8+ T cell response. J Immunol. 2007;178:5429–5433. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patek PQ, Collins JL, Cohn M. Transformed cell lines susceptible or resistant to in vivo surveillance against tumorigenesis. Nature. 1978;276:510–511. doi: 10.1038/276510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muranski P, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy of cancer using CD4(+) T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, Briere F, Galizzi JP, van Kooten C, et al. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chattopadhyay PK, Yu J, Roederer M. A live-cell assay to detect antigen-specific CD4+ T cells with diverse cytokine profiles. Nat Med. 2005;11:1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/nm1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frentsch M, Arbach O, Kirchhoff D, Moewes B, Worm M, Rothe M, et al. Direct access to CD4+ T cells specific for defined antigens according to CD154 expression. Nat Med. 2005;11:1118–1124. doi: 10.1038/nm1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alisa A, Ives A, Pathan AA, Navarrete CV, Williams R, Bertoletti A, et al. Analysis of CD4+ T-Cell responses to a novel alpha-fetoprotein-derived epitope in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6686–6694. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bricard G, Bouzourene H, Martinet O, Rimoldi D, Halkic N, Gillet M, et al. Naturally acquired MAGE-A10- and SSX-2-specific CD8+ T cell responses in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol. 2005;174:1709–1716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizukoshi E, Nakamoto Y, Marukawa Y, Arai K, Yamashita T, Tsuji H, et al. Cytotoxic T cell responses to human telomerase reverse transcriptase in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2006;43:1284–1294. doi: 10.1002/hep.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang XY, Chen HS, Zhang HG, Pang XW, Qiao H, Peng JR, et al. The spontaneous CD8+ T-cell response to HLA-A2-restricted NY-ESO-1b peptide in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6946–6955. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon H, Lee H, Kim HJ, You KT, Park YN, Kim H. Tudor domain-containing protein 4 as a potential cancer/testis antigen in liver cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 224:41–46. doi: 10.1620/tjem.224.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grizzi F, Franceschini B, Hamrick C, Frezza EE, Cobos E, Chiriva-Internati M. Usefulness of cancer-testis antigens as biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2007;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Meng WS, Dissette VB, Amarnani S, Vu HT, et al. T-cell responses to HLA-A*0201 immunodominant peptides derived from alpha-fetoprotein in patients with hepatocellular cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5902–5908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding FX, Wang F, Lu YM, Li K, Wang KH, He XW, et al. Multiepitope peptide-loaded virus-like particles as a vaccine against hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;49:1492–1502. doi: 10.1002/hep.22816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komori H, Nakatsura T, Senju S, Yoshitake Y, Motomura Y, Ikuta Y, et al. Identification of HLA-A2- or HLA-A24-restricted CTL epitopes possibly useful for glypican-3-specific immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2689–2697. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motomura Y, Senju S, Nakatsura T, Matsuyoshi H, Hirata S, Monji M, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived dendritic cells expressing glypican-3, a recently identified oncofetal antigen, induce protective immunity against highly metastatic mouse melanoma, B16-F10. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2414–2422. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuang M, Peng BG, Lu MD, Liang LJ, Huang JF, He Q, et al. Phase II randomized trial of autologous formalin-fixed tumor vaccine for postsurgical recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1574–1579. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee WC, Wang HC, Hung CF, Huang PF, Lia CR, Chen MF. Vaccination of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells: a clinical trial. J Immunother. 2005;28:496–504. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000171291.72039.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Longato L, de la Monte S, Kuzushita N, Horimoto M, Rogers AB, Slagle BL, et al. Overexpression of insulin receptor substrate-1 and hepatitis Bx genes causes premalignant alterations in the liver. Hepatology. 2009;49:1935–1943. doi: 10.1002/hep.22856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ince N, de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Overexpression of human aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase is associated with malignant transformation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1261–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xian ZH, Zhang SH, Cong WM, Yan HX, Wang K, Wu MC. Expression of aspartyl beta-hydroxylase and its clinicopathological significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:280–286. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davila E, Kennedy R, Celis E. Generation of antitumor immunity by cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope peptide vaccination, CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide adjuvant, and CTLA-4 blockade. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3281–3288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valmori D, Souleimanian NE, Tosello V, Bhardwaj N, Adams S, O'Neill D, et al. Vaccination with NY-ESO-1 protein and CpG in Montanide induces integrated antibody/Th1 responses and CD8 T cells through cross-priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8947–8952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703395104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, Conry RM, Miller DM, Treisman J, et al. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2119–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ku GY, Yuan J, Page DB, Schroeder SE, Panageas KS, Carvajal RD, et al. Single-institution experience with ipilimumab in advanced melanoma patients in the compassionate use setting: lymphocyte count after 2 doses correlates with survival. Cancer. 116:1767–1775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peggs KS, Quezada SA, Korman AJ, Allison JP. Principles and use of anti-CTLA4 antibody in human cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizukoshi E, Nakamoto Y, Arai K, Yamashita T, Sakai A, Sakai Y, et al. Comparative analysis of various tumor-associated antigen-specific t-cell responses in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;53:1206–1216. doi: 10.1002/hep.24149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeung YA, Finney AH, Koyrakh IA, Lebowitz MS, Ghanbari HA, Wands JR, et al. Isolation and characterization of human antibodies targeting human aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase. Hum Antibodies. 2007;16:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy R, Celis E. Multiple roles for CD4+ T cells in anti-tumor immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:129–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.