Abstract

The majority of children with congenital heart disease now live into adulthood due to the remarkable surgical and medical advances that have taken place over the past half century. Because of this, the adults now represent the largest age group with adult cardiovascular diseases. They include patients with heart diseases that were not detected or not treated during childhood, those whose defects were surgically corrected but now need revision due to maladaptive responses to the procedure, those with exercise problems, and those with age-related degenerative diseases. Because adult cardiovascular diseases in this population are relatively new, they are not well understood. It is therefore necessary to understand the molecular and physiological pathways involved if we are to improve treatments. Since there is a developmental basis to adult cardiovascular disease, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling pathways that are essential for proper cardiovascular development may also play critical roles in the homeostatic, repair and stress response processes involved in adult cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, we have chosen to summarize the current information on a subset of TGFβ ligand and receptor genes and related effector genes that when dysregulated are known to lead to cardiovascular diseases and adult cardiovascular deficiencies and/or pathologies. A better understanding of the TGFβ signaling network in cardiovascular disease and repair will impact genetic and physiologic investigations of cardiovascular diseases in elderly patients and lead to an improvement in clinical interventions.

Keywords: TGFbeta, aging, disease, cardiovascular, heart

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is extremely common in elderly patients and is their leading cause of morbidity and death, more so than (Jackson and Wenger 2011)cancer (Roger et al. 2011). Congenital heart disease represents the largest class of birth defects and affects about 0.8% of all babies born (Supino et al. 2006). As a result of improved medical and surgical management of congenital cardiovascular malformations, 90% of children born with congenital heart diseases now live into adulthood. Because of this, adult congenital cardiovascular disease now represents the largest population in the United States living with the consequences of the repaired congenital cardiovascular malformations (Khairy et al. 2008). The aging affects other organs and the higher susceptibility of the elderly patients to other diseases such as diabetes is other factors that can influence cardiovascular complications (Roger et al. 2011). Common long-term problems include rhythm problems, valve problems, heart failure and aortic aneurysm (Pearson et al. 2008;Markwald et al. 2010) (Hinton and Yutzey 2011;Force et al. 2010;Lipshultz et al. 2003). Once developed, however, these cardiovascular tissues must undergo homeostasis to maintain function throughout life, and to undergo repair and remodeling following stress and injury. It stands to reason that these homeostatic and repair functions would use many of the same mechanisms that were involved in the development and remodeling of those tissues during embryogenesis. Thus, many genes associated with transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling that lead to congenital heart disease when disrupted (Arthur and Bamforth 2011;Derynck and Akhurst 2007;Dunker and Krieglstein 2000) would therefore be ideal candidates for homeostatic, stress response and repair processes in the adult (Fig. 1).

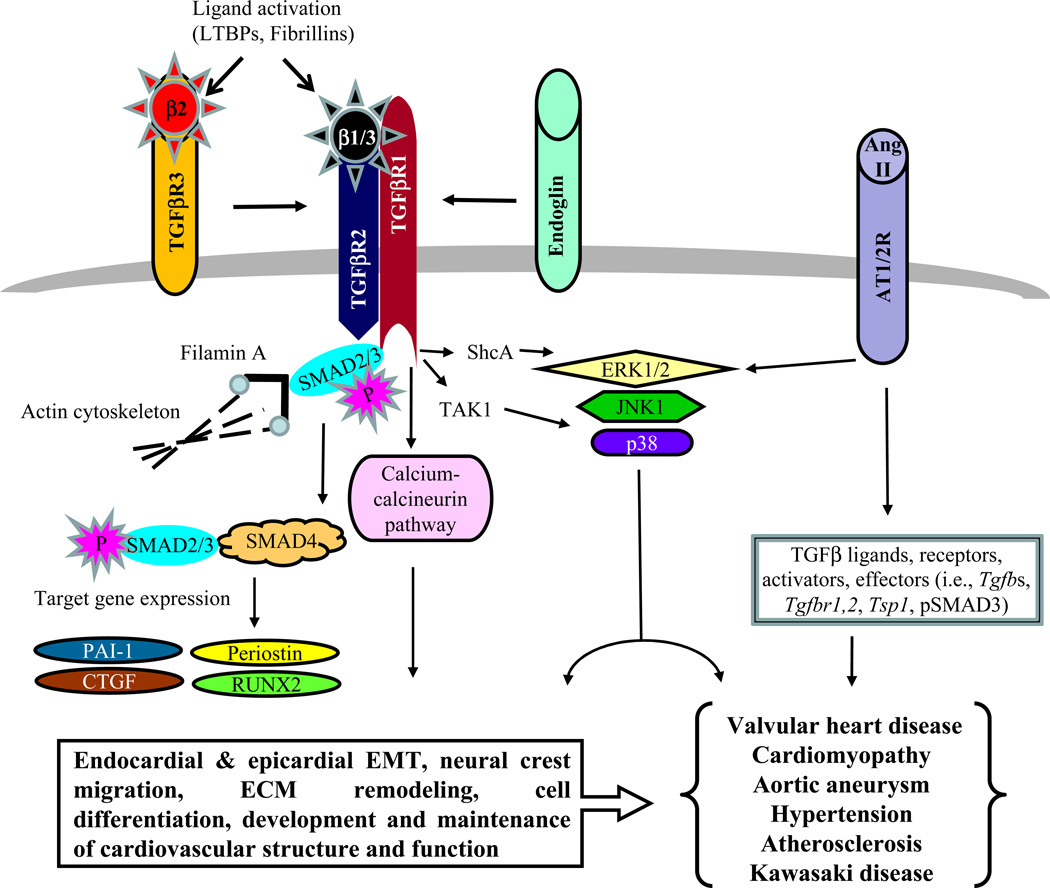

Fig. 1.

TGFβ signaling pathway and its integration with other major pathways that is likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases in elderly patients. The canonical TGFβ pathway involves SMADs. The non-canonical TGFβ pathways include several SMAD-independent signaling cascades such as calcium-calcineurin and MAPK pathways. The Ang II pathway can interact with TGFβ signaling through both SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent pathways (see text for details).

Genetic mutations in TGFβ pathway genes and TGFβ signaling dysregulation have emerged as a major molecular pathway involved in adult cardiovascular diseases (Table 1) (Gordon and Blobe 2008;ten Dijke and Arthur 2007;Jain et al. 2009) A striking number of these cardiovascular defects are modeled in mice with mutations or dysregulation in TGFβ signaling and effector genes (Arthur and Bamforth 2011). Unfortunately, the complexity of TGFβ signaling often plays itself out in seemingly inconsistent fashion when one investigates its roles in human cardiovascular disease, in mouse models of cardiovascular disease, and in TGFβ-based pre-clinical and clinical therapeutic outcomes. A critical barrier to progress in the field of adult cardiovascular diseases, in which TGFβ and related pathways are potential therapeutic targets, is the poor understanding of the interrelated pathways by which three TGFβ ligands can signal through multiple combinations of TGFβ receptors, and then transduce signals through several SMAD-dependent and -independent pathways (Fig. 1) (Kang et al. 2009;Moustakas and Heldin 2009). In this review we will provide a summary of the potential involvement of TGFβ signaling molecules in cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular stress-related complications, and the prospect of the TGFβ-based therapeutics in the field.

Table 1.

Genetic mutation or variation associated with human cardiovascular diseases

| Gene | Disease | Cardiovascular complications (Reference) |

|---|---|---|

| TGFB Ligands | ||

| TGFB2 | Kawasaki disease | Coronary artery aneurysm, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death (Shimizu et al. 2011) |

| TGFB3 | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular-cardiomyopathy/ dysplasia | Fibro-fatty replacement of myocardium, abnormal rhythms, RV and LV dysfunction, sudden cardiac death (Beffagna et al. 2005) |

| TGFB Receptors | ||

| TGFBR1 | Loeys-dietz syndrome, | Aortic aneurysm, valvuloseptal defects, cardiac dysfunction, other congenital heart defects (Loeys et al. 2006) |

| Kawasaki disease | See above | |

| TGFBR2 | Loeys-dietz syndrome | See above |

| Marfan syndrome-related disorders | Aortic aneurysm, mitral valve disease, cardiac dysfunction (Mizuguchi et al. 2004) | |

| Familial thoracic ascending aortic aneurysm-and dissection | Ascending aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection or rupture (Jain et al. 2009) | |

| TGFBR3 | Familial intracranial aneurysm | Cerebral artery aneurysm (Santiago-Sim et al. 2009) |

| ENDOGLIN | Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | Vascular dysplasia leading to telangiectases and arteriovenous malformations, aortic aneurysm (ten Dijke and Arthur 2007) |

| TGFB effectors | ||

| FLNA | X-linked cardiac valvular disease | Valvular hypertrophy (Kyndt et al. 2007) |

| SMAD3 | Aortic aneurysm-osteoarthritis | Arterial aneurysm, congenital heart disease, valve and myocardial disease (van, I et al. 2011) |

| SMAD4 | Juvenile polyposis syndrome with cardiovascular complication | Aortopathy, mitral valve disease (Andrabi et al. 2011) |

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | See above |

TGFβ signaling and functional complexity

TGFβs 1, 2 & 3 control a plethora of cellular processes, including epithelial mesenchymal transformation, cell growth, apoptosis, differentiation, extracellular matrix (ECM) production and remodeling, all in a highly context-dependent manner (Sporn 2006;Barnard et al. 1990;Sporn and Roberts 1990;Massague et al. 1994;Mercado-Pimentel and Runyan 2007;Derynck and Akhurst 2007). TGFβ2 interacts with TGFβR3 to allow high affinity binding to TGFβR2 and TGFβR1 receptor complex (Lopez-Casillas et al. 1993). Endoglin is an accessory protein that cannot bind ligand on its own but interacts with the signaling receptor complex of multiple members of the TGFβ superfamily (Barbara et al. 1999). Since TGFBR2 can only bind TGFβ1 and TGFβ3, endoglin signals for these ligands when it is present in the TGFβ receptor complex (Yamashita et al. 1994). This ligand-receptor binding results in phosphorylation and activation of TGFβR1, which leads to phosphorylation-dependent activation SMAD2/3 (Fig. 1). In association with SMAD4 the phosphorylated SMAD2/3 molecules migrate to the nucleus (Wu and Hill 2009). In conjunction with corepressors and coactivators the SMAD complex regulates TGFβ target genes, including periostin (Postn), connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) and platelet activator inhibitor-1 (Pai1) (Ross and Hill 2008;Snider et al. 2009;Moustakas and Heldin 2009). Recent findings have highlighted some cross-utilization of ligand and receptors between TGFβ and BMP subfamilies. As with the TGFβs, ligands of the BMP subfamily also signal through a variety of Type I and Type II receptors from which transduction occurs via SMADs 1, 5 & 8 (Miyazono et al. 2010;Wang et al. 2011). TGFβ1 can also signal through ALK1 (a BMP Type I receptor) in endothelial cells (Lebrin et al. 2005), and ALK2 (a BMP Type I receptor) in both endothelial cells and fibroblasts (Daly et al. 2008), thereby bringing about cross-talk between TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways. It has also been well documented that TGFβR3, a TGFβ2-binding receptor, can also bind to BMP2 and lead to epithelial-mesenchymal transformation during heart development (Townsend et al. 2011). The inhibitory SMAD6 predominantly inhibits BMP signaling, whereas SMAD7 inhibits both TGFβ and BMP signaling (Goto et al. 2007;Tang et al. 2010). It is clear that growth, differentiation, morphogenetic and matrix modeling properties of TGFβ, properties that have been associated with TGFβ function for decades (reviewed (Roberts et al. 1990a;Roberts et al. 1990b;Barnard et al. 1990)), are critical for the proper development of the heart (reviewed (Azhar et al. 2003;Barnett and Desgrosellier 2003;Runyan et al. 2005;Camenisch et al. 2010;Arthur and Bamforth 2011)) and for cardiac function (reviewed (Azhar et al. 2003;Snider et al. 2009)). Given the non-overlapping (Sanford et al. 1997), multifunctional nature of TGFβ function (dozens of phenotypes among the 3 TGFβ ligand knockout mice, reviewed (Doetschman 1999)), as well as the multiple TGFβ signaling pathways that have been identified (Moustakas and Heldin 2009), there are numerous potential mechanisms through which TGFβ affects the complex differentiation and morphogenetic processes required to develop the heart’s components.

Consistent with the theme that TGFβ signaling pathways that are essential for proper cardiovascular development also play critical roles in the cardiovascular system during the aging process, we have chosen to focus on TGFβ ligand and receptor genes and related effector genes that when dysregulated or mutated are known to lead to congenital heart disease and cardiovascular deficiencies and/or pathologies during aging. A schematic depicting the interaction of the TGFβ-associated genes is presented in Fig. 1 and is discussed (see below).

Genetic variation and dysregulated expression of TGFB ligand genes in cardiovascular diseases

Genetic mutations affecting TGFβ signaling has been reported in patients with cardiovascular diseases, including arterial aneurysm, valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathy (Table 1). Elevated TGFβ signaling (pSMAD2 as an indicator) was reported in cardiovascular patients of Marfan syndrome (MFS: aortic aneurysm and dissection, mitral valve prolapse), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS: mitral valve prolapse, aortic root dilation, aneurysm), Cutis Laxa (aortic aneurysm and stenosis), Arterial Tortuosity syndrome (ATS: aneurysm and aortic stenosis), Bicuspid Aortic Valve with aortic aneurysm, Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS: aortic aneurysm, congenital heart defects), and aortic aneurysms and dissections with early-onset osteoarthritis (AOS: aneurysm/dissection, valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation) (Jain et al. 2009;Matt et al. 2009;Loeys et al. 2005;Coucke et al. 2006;Loeys et al. 2006;Renard et al. 2010;van, I et al. 2011). Notably, what makes these TGFβ-associated cardiovascular diseases of children, youth and adults more challenging is that they affect many cardiovascular tissues in the same patients (Eckman et al. 2009;Das et al. 2006;De Backer 2009a). There are also many non-syndromic cardiovascular disorders in which TGFβ signaling is increased. TGFβ1 is elevated in calcified human aortic valves (Jian et al. 2003), and increased levels of TGFβ1 are found in humans with chronic rheumatic heart disease (Kim et al. 2008) and carcinoid syndrome (Jian et al. 2002). Both elevated levels of TGFβ1 and pSMAD2 are associated with non-syndromic ascending aortic aneurysm in humans (Gomez et al. 2009).

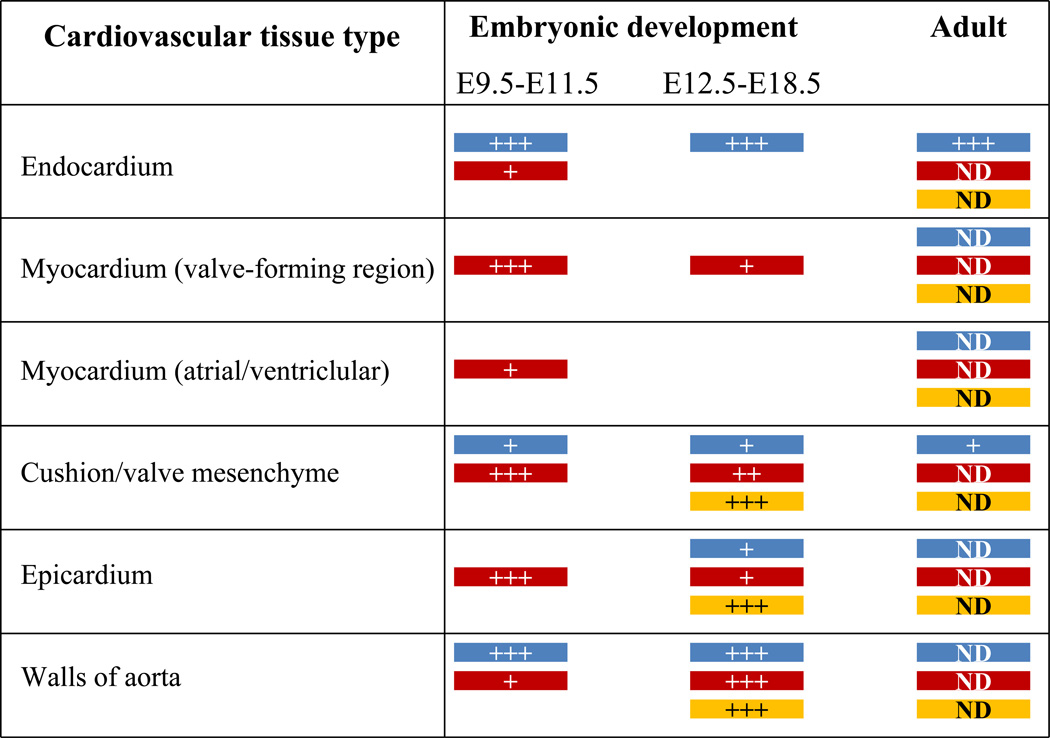

Patients of both idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy have increased levels of TGFB1 in the myocardium (Li et al. 1997;Pauschinger et al. 1999). TGFβ1 is also increased in myocardial remodeling in patients with valvular aortic stenosis as evidenced by left ventricular transcriptional changes of genes linked to myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, and by heart morphology and function (Villar et al. 2009). Consistent with these observations, mice subjected to transverse aortic constriction have elevated TGFβ1 (Villar et al. 2009), and in TGFβ1-deficient mice we found that Angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced cardiac hypertrophy is attenuated (Schultz et al. 2002). TGFβ1 also plays an important role in attenuating hypertension in mice (Zacchigna et al. 2006). In addition, there are elevated levels of TGFB1–3 in aortas of Marfan syndrome patients associated with altered hyaluronan synthesis, increased apoptosis, impaired progenitor cell recruitment, and abnormal directional migration, suggesting that defective tissue repair is likely to contribute to aortic disease in these patients (Nataatmadja et al. 2006). Consistently, TGFβ1 levels are found to be elevated in valvular and aortic tissues of Fibrillin-1+/C1039G mice, a Marfan syndrome mouse model (Ng et al. 2004;Habashi et al. 2006). Genetic polymorphism (Leu(10)-->Pro (codon 10)) in the human TGFB1 gene is associated with end-stage heart failure caused by dilated cardiomyopathy (Holweg et al. 2001). Renal dysfunction is a severe late complication of heart transplantation, and renal function decreases in most heart transplantation recipients with time. Progression of renal insufficiency worsens in patients with Leu at codon 10 polymorphism in TGFB1 (Lacha et al. 2001). In mouse, Tgfb1 gene expression is seen predominantly in endocardium in the heart and endothelium of the arterial walls during cardiovascular development and at neonatal stages (Fig. 2) (Molin et al. 2003;Akhurst et al. 1990). Gene targeted disruption of Tgfb1 has revealed variable genetic background-dependent phenotypes in mice (Sanford et al. 2001). Depending on the mouse genetic background the loss of Tgfb1 could lead to embryonic lethality caused by either preimplantation defects or defective vasculogenesis and hematopoiesis of the extraembryonic tissues such as yolk sac, and an autoimmune disease at weaning age (Kallapur et al. 1999;Shull et al. 1992;Kulkarni et al. 1995;Dickson et al. 1995). Several genetic modifier loci have been identified that influence Tgfb1 knockout mouse phenotypes (Bonyadi et al. 1997). Because of these complex phenotypes the exact physiological role of TGFβ1 in cardiovascular development and function has not been elucidated.

Fig. 2.

Summary of gene expression patterns of the three TGFβ ligand genes in cardiovascular tissues during embryonic development and adulthood. The data is collected from various in situ hybridization studies (see text for details). Blue, Tgfb1; Brown, Tgfb2; Yellow, Tgfb3. +, presence of gene expression; ++ higher intensity of gene expression; +++, highest level of gene expression; ND, not determined.

Genetic variation in TGFB2 has also been reported in association with cardiovascular complications in patients of Kawasaki disease (Shimizu et al. 2011) (Table 1). Kawasaki disease is an inflammatory disease in which death is often caused by coronary artery aneurysm, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease and sudden cardiac death. TGFB2 levels are elevated in the myocardial tissue of the patients of dilated cardiomyopathy (Pauschinger et al. 1999). In mouse, Tgfb2 expression has been reported in myocardium surrounding the valve forming regions, valve mesenchyme, and arterial wall of the pharyngeal arch artery system during cardiovascular development (Fig. 2) (Dickson et al. 1993;Azhar et al. 2003;Molin et al. 2003). Gene targeted disruption of Tgfb2 in mice has resulted in valvuloseptal and myocardial defects, enlarged valves, and defects in aortic arch artery development and remodeling. (Sanford et al. 1997;Bartram et al. 2001;Azhar et al. 2009a;Azhar et al. 2011). Furthermore, TGFB2 is elevated in diseased mitral valves and aortas of Marfan syndrome patients in which TGFβ signaling is also increased (Ng et al. 2004;Nataatmadja et al. 2006;Jain et al. 2009). The expression of Tgfb2 in adult mouse cardiovascular tissues has not been determined, and therefore it is difficult to predict its possible role in adult cardiovascular structure and function. There are also no reports on Tgfb2 transgenic overexpression in mouse cardiovascular tissues. Overall, the role of TGFβ2 in the adult cardiovascular system and in cardiovascular diseases remains to be understood.

Significant expression of the TGFB3 gene has been detected in human hearts (Rampazzo et al. 2003). Importantly, genetic mutations are found in TGFB3 in patients of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/ dysplasia (ARVC/D or ARVD1) (Rampazzo et al. 2003;Beffagna et al. 2005;McNally et al.). In addition, a genetic polymorphism in TGFB3 is associated with the abnormal left ventricular structure-function in hypertensive patients (Hu et al. 2010). ARVD is considered a leading cause of unexpected sudden cardiac death, particularly in the young and in athletes. ARVD is a genetic, progressive heart condition in which the muscle of the right ventricle is replaced by fat and fibrosis which cause abnormal heart rhythms. ARVD primarily affects the right ventricle; with time, it may also involve the left ventricle. Familial ARVD disease is common, and it is transmitted as an autosomal dominant disorder. ARVD has been linked to several chromosomal loci, and therefore, a single gene change is usually not sufficient for the development of ARVD, and genetic interaction among various genes is needed for an individual to actually develop symptoms of ARVD (Tran-Fadulu et al. 2009;Uddin et al. 2010). Although it is thought that the causative factor in ARVD1 could be paradoxically increased TGFβ signaling (Beffagna et al. 2005), it is currently unclear how mutations in TGFB3 actually cause ARVD. The only clues about TGFβ3 function at an organismal level have come from mouse gene targeting studies. Tgfb3−/− mice died at birth due to cleft palate (Proetzel et al. 1995;Kaartinen et al. 1995), and they have a subtle myocardial and aortic phenotype (Azhar et al. 2003). Although Tgfb3 expression appears much later than Tgfb2 during cardiovascular development in wild-type embryos, its patterns of expression are strikingly similar to that of Tgfb2 (Fig. 2) (Molin et al. 2003). Also, Tgfb3 expression increases as compared to Tgfb2 as cardiovascular development proceeds (Vrljicak et al. 2010). This raises a possibility whether TGFβ2 plays a dominant role during early stages of cardiovascular development; whereas, TGFβ3 could represent the predominant TGFβ isoform during later stages of cardiovascular remodeling, a suggestion consistent with the mutations in TGFB3 in adult cardiac disease patients. Such speculation is also consistent with the observation that genetic deletion of Tgfb3 in Tgfb2−/− embryos worsens embryonic developmental phenotypes of Tgfb2−/− embryos (Dunker and Krieglstein 2002). Consequently, determination of Tgfb3 expression in adult cardiovascular tissues and its exact physiological function in the adult cardiovascular system will lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of adult cardiovascular diseases. Overall, direct contribution of specific TGFβ ligands or combinations of different TGFβ ligands to the TGFβ signaling in vivo in cardiovascular disease/disorders remains a complete mystery that needs to be resolved.

Connection between TGFβ receptor mutations and cardiovascular diseases

Genetic mutations in TGFBR2 and TGFBR1 are found in patients of arterial aneurysms, including Loeys-Dietz syndrome and other Marfan syndrome-like disorders (Table 1) (Loeys et al. 2006;Mizuguchi et al. 2004). The TGFBR2 mutation is also described in patients of non-syndromic or familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections (Jain et al. 2009). Many patients of Kawasaki disease, which have cardiovascular complications, also have a mutated TGFBR2 (Shimizu et al. 2011). A dominant-negative effect was demonstrated for most mutations associated with Marfan syndrome-related disorders. By contrast, the R460C mutation, which has been found in familial aneurysms but not in syndromic patients, showed a less-severe dominant-negative effect and retained residual SMAD phosphorylation and transcriptional activity (Horbelt et al. 2010). In cell culture experiment mutations in TGFBR2 can inhibit SMAD2/3 activation, those same mutations have the potential to cause increased SMAD1/5 activation (Bharathy et al. 2008). Quite paradoxically, the cardiovascular tissues from Loeys-Dietz syndrome patients, which have loss-of-function TGFBR2/1 mutations, show elevated pSMAD2 and TGFβ target gene expression (Loeys et al. 2005;Loeys et al. 2006). Although Tgfbr2 and Tgfbr1 conditional deletion in mice has revealed important tissue-specific roles of these receptors in cardiovascular development, these studies have failed to generate any direct information about their function in adult cardiovascular tissues and in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases (Jiao et al. 2006;Choudhary et al. 2009;Sridurongrit et al. 2008;Robson et al. 2010) (Langlois et al. 2010). Overall, the cell autonomous and non-autonomous aspects of the genetic mutations in TGFB receptor genes remain unclear. Adult mouse models mimicking these TGFβ receptor mutations will be useful to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship between the mutations and the adult cardiovascular complications seen in patients. It is also important to note that individuals with many of these TGFB receptors gene mutation-containing syndromes, in which there is failed matrix regulation possibly due to elevated and/or reduced TGFβ signaling, share phenotypes similar to those seen in TGFβ2-deficient mice; e.g., craniofacial/skeletal, cleft palate, ocular defects and congenital heart disease (Sanford et al. 1997;Saika et al. 2001;Paradies et al. 1998;Crowe et al. 2000;Jain et al. 2009;Horbelt et al. 2010;Mizuguchi et al. 2004). Conditional deletion of the Tgfbr1 and/or Tgfbr2 in different cardiovascular cell types has also produced similar results (reviewed in (Arthur and Bamforth 2011)).

Genetic variants have been identified in TGFBR3 and endoglin in familial intracranial aneurysm (Table 1) (Santiago-Sim et al. 2009). Due to ENDOGLIN mutations in HHT patients the role of endoglin in cardiovascular development and disease has caught significant attention (Goumans et al. 2008;Nomura-Kitabayashi et al. 2009;Mercado-Pimentel et al. 2007;Arthur et al. 2000), and therefore has not been reviewed here. Despite our ever increasing understanding of TGFβ signaling, especially downstream of the canonical receptors TGFβR2 & TGFβR1, the diverse and often contradictory actions of TGFβ remain unexplained. A critical component of TGFβ signaling that is not well understood and understudied is the contribution of TGFβR3 (Lopez-Casillas et al. 1993). Although TGFβR3 augments the canonical TGFβ signaling pathway, several lines of evidence establish a unique role for TGFβR3 in mediating the actions TGFβ. First, TGFβR3 binds all 3 TGFβ ligands in addition to BMP’s (notably BMP-2) (Kirkbride et al. 2008) and inhibin (Lewis et al. 2000). All these ligands are members of the TGFβ superfamily of growth factors. Second, TGFβR3 localizes endocardial to mesenchymal transformation to the AV cushion, and its inhibition prevents endocardial transformation and migration (Brown et al. 1999). This system provided the first report demonstrating that TGFβR3 was specifically required to mediate a biological event. Third, targeted deletion of Tgfb2, which requires TGFβR3 for high affinity binding, results in embryos with a unique and nonoverlapping cardiovascular phenotype compared to Tgfb1 and Tgfb3 knockout embryos (Azhar et al. 2003). Finally, deletion of Tgfbr3 results in embryos with defects distinct from those seen in Tgfbr1 and Tgfbr2 knockout embryos, including defects in the outflow tract, valves, coronary vessels and myocardium (Stenvers et al. 2003;Compton et al. 2007;Arthur and Bamforth 2011). Comparison of heart defects in Tgfbr3 and Tgfb2 knockout embryos indicates common and unique roles for TGFβR3 and TGFβ2 in heart development (Azhar et al. 2003;Stenvers et al. 2003;Compton et al. 2007). A human GWAS identified a TGFBR3 single nucleotide polymorphism with significantly altered bone mineral density (Xiong et al. 2009). Recent findings have indicated that BMP2 can also bind and act as a ligand for TGFβR3 (Townsend et al. 2011). BMP2 has well documented role in bone biology and aortic valve calcification (Wang et al. 2011;Miyazono et al. 2010;Hakuno et al. 2009). Since the heart and vascular wall of aorta and bone share similar molecular pathways (Rajamannan 2009;Lincoln et al. 2006), this suggests a potential role for TGFBR3 in calcific cardiovascular diseases, including aortic valve and vascular calcification. Overall, these observations suggest an important role for TGFβR3 in TGFβ signaling. Understanding the biological roles of TGFβR3 is essential to further our understanding of TGFβ signaling and the role of different TGFβ ligands, particularly of TGFβ2-TGFβR2 ligand-receptor pair, in development and disease. Even in conditions such as Marfan syndrome and aortic aneurysm where recent insights into the role of TGFβ have significantly impacted clinical care and outcomes, there is general recognition that our understanding is inadequate to fully explain and leverage therapeutic opportunities (reviewed in (Dietz 2010)). Delineating TGFβ ligand(s) and receptor(s) interaction pathways involved in specific aspects of cardiovascular development and adult cardiovascular function should inform novel therapeutic approaches with higher specificity and more limited side effects.

TGFβ effector molecules in cardiovascular diseases

Canonical TGFβ signaling is mediated by combination of various SMADs, which are widely expressed in cardiovascular tissues (Luukko et al. 2001). Aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome is a newly described syndrome, which is caused by mutations in SMAD3 (van, I et al. 2011). These patients have aneurysms, dissections and tortuosity throughout the arterial tree in association with mild craniofacial features and skeletal and cutaneous anomalies. In contrast with other aneurysm syndromes, most of these affected individuals present with early-onset osteoarthritis (van, I et al. 2011;Jain et al. 2009). These patients also have other (congenital) heart diseases, such as persistent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, pulmonary valve stenosis and atrial fibrillation. Mitral valve abnormalities, ranging from mild valve prolapse to severe regurgitation requiring valve replacement, and idiopathic mild-to-moderate predominantly concentric left ventricular hypertrophy have also been reported in these patients. Intriguingly, as in Marfan-syndrome like disorders, heterozygous SMAD3 mutations in humans are also associated with increased aortic expression of several key players in the TGFβ pathway, including pSMAD3. In addition, genetic variation in SMAD3 is also associated with Kawasaki disease susceptibility, coronary artery aneurysm formation, aortic root dilatation, and intravenous immunoglobulin treatment response in different cohorts (Table 1) (Shimizu et al. 2011). SMAD3 is also an important player in T-cell activation and cardiovascular remodeling, both of which are important features of Kawasaki disease (Roberts et al. 2006). A recent mouse genetic study has shown that SMAD3 plays a beneficial role in delimiting cardiac hypertrophic response and that SMAD3 has a detrimental effect on myocardial fibrosis (Divakaran et al. 2009). Importantly, a highly specific pharmacological agent, SIS3, exists which can effectively block SMAD3 signaling without affecting SMAD2 activation (Jinnin et al. 2006). SIS3 has been shown to block in vivo SMAD3 signaling in a mouse model (Li et al. 2010). Collectively, these findings endorse the SMAD3 as a critical effector of TGFβ signaling and as a potential pharmacological target for the development of new treatments for adult cardiovascular disease.

The phosphorylated SMAD3 forms a complex with SMAD4, which enters the nucleus. This SMAD complex binds promoters and causes the transcription of target genes (Moustakas and Heldin 2009;Ross and Hill 2008). A recent study has reported that mutations in SMAD4 are also involved in aortopathy and mitral valve dysfunction, in addition to Juvenile polyposis syndrome (Andrabi et al. 2011). SMAD4 mutations are a major cause of Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), a syndrome characterized by the appearance of multiple polyps in the gastrointestinal tract. Individuals with this condition due to mutations in SMAD4 are at greater risk to manifest signs of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT), a clinical condition which can also be caused by other mutated genes that modulate TGFβ signaling (e.g., ENG, ALK1) (ten Dijke and Arthur 2007). Partial deletion of Smad4 (haploinsuffciency) results in premature death caused by the worsening of aortic aneurysm and rupture in mouse of model of Marfan syndrome (Holm et al. 2011). In addition, Smad4 plays important roles in valves and myocardium during cardiac development (Azhar et al. 2010;Nie et al. 2008;Moskowitz et al. 2011). Furthermore, conditional loss of Smad4 in myocardium can cause spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy (Song et al. 2007). Collectively, SMAD4 serves as a nodal point where the majority of canonical TGFβ signaling can converge and regulate cardiovascular development and adult tissue homeostasis.

Recent genetic studies have demonstrated that an X-linked myxomatous valvular dystrophy (XMVD) can be attributed to mutations in the Filamin-A (FLNA) gene (Table 1) (Kyndt et al. 2007). Genetic mutations in FLNA are also associated with a cardiological phenotype with aortic or mitral regurgitation, coarctation of the aorta or other left-sided malformations (de Wit et al. 2011). The cytoskeletal protein filamin A (FLNA) connects the actin filament network to membrane receptors and acts as a scaffold protein for signal transduction molecules, including SMADs (Sasaki et al. 2001). In FLNA-deficient cells TGFβ does not induce SMAD2 phosphorylation and subsequent SMAD translocation to the nucleus does not occur. Reintroduction of FLNA to these mutant cells restores TGFβ responsiveness (Sasaki et al. 2001). The FLNA is robustly expressed in non-myocyte cells throughout cardiac morphogenesis including epicardial and endocardial cells, and mesenchymal cells derived by epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) from these two epithelia, as well as mesenchyme of neural crest origin. In adult hearts, expression of FLNA is significantly decreased in the atrioventricular (AV) and outflow tract valve leaflets and their suspensory apparatus (Norris et al. 2010). Overall, genetic mutation analysis and gene expression and biochemical studies suggest that FLNA is a critical TGFβ effector molecule involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases of adults. Overall, FLNA and SMADs are important downstream effectors of TGFβ ligand-receptor signaling involved cardiovascular development, homeostasis and disease pathogenesis.

Role of TGFβ target genes in cardiovascular diseases

In this section we will summarize the published literature on RUNX2 and periostin as two potential TGFβ target molecules that may play important roles in pathogenesis of adult cardiac disease (Fig. 1). These genes are chosen because they regulate ECM remodeling and organization and calcification, both of which are critical properties of adult cardiovascular homeostasis. Involvement of TGFβ in valvular calcification was first reported in the 1990s (Watson et al. 1994a), but roles of the TGFβ superfamily members still remain obscure (Xu et al. 2010). Valve calcification in the adult is substantial. Degenerative valve disease occurs in approximately 25% of individuals over 65, and while there is a substantial literature describing calcium, protein and lipid components of valve pathology, the etiology of the process is not well understood. Aortic valve stenosis is the most frequent complication for valve repair or replacement surgery, and is commonly associated with pathologic calcification. Degenerative disease incidence does increase with age, but studies suggest that valve disease is not inevitable and that an understanding could be translated into preventive measures (Soler-Soler and Galve 2000). Aortic valve calcification is the predominant pathology in valve transplant patients (Subramanian et al. 1984). Also, mitral annular calcification is one of the most common cardiac defects found upon autopsy, it is occasionally found in Marfan syndrome patients, and it is significantly associated with aortic stenosis, aortic and mitral valve regurgitation, left ventricular hypertrophy and functional deficiency (Movahed et al. 2007;De Backer 2009b). Analysis of calcified aortic valve cusps found increased TGFβ1 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), suggesting that both calcification and associated tissue remodeling are induced by TGFβ and its downstream remodeling genes (Jian et al. 2003;Clark-Greuel et al. 2007). It has been demonstrated that genetic inactivation of Tgfb2 leads to severe bone defects (Sanford et al. 1997), that TGFβ1 stimulates calcification in cells with osteoblastic potential (Watson et al. 1994b), that explanted calcified nodules from transplanted tissues increase calcification in response to TGFβ1 (Mohler, III et al. 1999), and that TGFβ1 induces calcification in porcine and ovine valve interstitial cells (Walker et al. 2004;Clark-Greuel et al. 2007). The mean concentration of TGFβ1 in patients with valvular heart disease is found to be significantly lower (18.67 µg/l) than in the control group, suggesting that the lower plasma concentration of TGFβ1 in patients with valvular heart disease, and the lack of its regulatory effect may be involved in the increased inflammation and calcification seen in valvular heart disease. Although TGFβ signaling is implicated in calcific and non-calcific (e.g., myxomatous degeneration and prolapse of mitral valve) valve diseases, the maturation of valve cells and the etiology of these pathologies, in relation to TGFβ, are not understood. With the exception of a few recent studies on the role of TGFβ in valve development (Azhar et al. 2011;Todorovic et al. 2011), there has not been a systematic examination of heart valve disease in mouse models related to TGFβ pathway genes that would shed light on the etiology of valve disease.

Runx2 (Cbfa1) is a TGFβ- and BMP-regulated gene, required for EMT, that also forms a transcription complex with SMAD proteins to regulate target gene expression (Franceschi et al. 2003). RUNX2 has been described as a “master regulator” of osteoblast differentiation and is required for chondrocyte hypertrophy (Stein et al. 2004;Napierala et al. 2008). Runx2 is also named Cbfa1, Aml3, Osf2 and Pepb2a (OMIM). In humans there are a variety of mutations in RUNX2, many of which affect the DNA binding domain or cause truncations of the C terminus and cause cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) in heterozygous form (Otto et al. 2002). Truncations in the C terminus prevent transcriptional regulation of target genes as they prevent interaction with TGFβ and BMP SMADs and block targeting to the nuclear matrix (Zhang et al. 2000). Runx2 is expressed in up to nine splice forms, but few are understood. Runx2(II) includes exon 1 (activation domain 1) while Runx2(I) begins with exon 2 and activation domain 2 (Li and Xiao 2007). Alternative splicing appears to regulate the expression of a short nuclear localization sequence or a nuclear matrix/SMAD binding domain in either the I or II isoforms (Makita et al. 2008). Runx2(II) isoform is expressed in bone and cartilage. The significance of two isoforms was examined in bone and catrilage development and differences are observed in formation of different bones (Xiao et al. 2004), but the heart was not examined. It is clear that the RUNX2(I) isoform preferentially interacts with the co-regulator CBFβ (Kundu et al. 2002) and alters its transcriptional activity. CBFβ is necessary for breast cancer invasion (Mendoza-Villanueva et al. 2010). Runx2 also induces expression of metalloproteinases in cancer cells that also play role in valvulogenesis (Pratap et al. 2005;Alexander et al. 1997).

A number of mouse mutations in Runx2 have been examined but, except for one mutant, they have all been mutations of both Runx2 isoforms and the analysis focused on the skeletal system as loss of Runx2 expression results in neonatal lethality and failure of bone formation (Otto et al. 1997). One mutant has a deleted first exon that enables expression of only Runx2(I), but analysis focused on a finding that commitment to the osteoblastic lineage was normal but osteoblastic differentiation was impaired, and only some bones were produced (Xiao et al. 2004). At the cell biological level, there has been investigation of RUNX2 role in cell proliferation (Pratap et al. 2003), and it is known that STAT1 can bind and sequester Runx2 in the cytoplasm (Kim et al. 2003). It was seen that Runx2(I) is expressed in prostate, breast and melanoma cancers, but the focus on this expression has been related to the tendency of these cancers to metastasize to bone (Pratap et al. 2006). Although RUNX2 expression in tumor cells and regulation of genes such as Mmp9 or Col Ia1 are consistent with a role in EMT, that relationship has not been exploited in the developing heart.

Another transcription factor with a described role in EMT, TWIST1, is known to inhibit RUNX2 activity and is regulated by BMP and TGFβ isoforms (Kronenberg 2004). Twist1, a class II basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor, is expressed during early endocardial cushion development and is down-regulated later during valve remodeling. The reported expression of Runx2 in the murine cardiac cushions warrants an investigation into a link between RUNX2 and TWIST1 in heart (Gitler et al. 2003). The requirements for Twist1-deficiency in the remodeling valves and the consequences of prolonged Twist1 activity were examined in mice. Twist1−/− mice have defective EMT (Shelton and Yutzey 2008) and abnormal valve remodeling (Chakraborty et al. 2010a). Persistent Twist1 expression in the remodeling valves leads to increased valve cell proliferation, increased expression of Tbx20, and increased ECM gene expression, characteristic of early valve progenitors. Increased Twist1 expression also leads to dysregulation of fibrillar collagen and periostin expression, as well as enlarged hypercellular valve leaflets prior to birth. In human diseased aortic valves, increased Twist1 expression and cell proliferation are observed adjacent to nodules of calcification (Chakraborty et al. 2010b). Furthermore, Runx2 is upregulated in the ApoE knockout mouse model of aortic valve disease (Aikawa et al. 2007), and also in human degenerative mitral valve and calcified aortic valve disease (Rajamannan et al. 2003;Caira et al. 2006). Thus, the presence of both Runx2 and Twist1 in calcified valves provides an avenue for TGFβ-mediated calcific valve disease.

Periostin has emerged as another major TGFβ-target gene involved in cardiac development and various adult cardiovascular pathologies (Fig. 1). Periostin is a secreted fasciclin-domain-containing protein, which is involved in both valve development and valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathy (Snider et al. 2008;Litvin et al. 2006;Hamilton 2008;Teekakirikul et al. 2010). In vitro studies indicate that Postn can be induced by TGFβ1 (Horiuchi et al. 1999;Zhou et al. 2010). TGFβ2-deficiency results in reduced periostin in cardiac fibroblasts (Snider et al. 2009). Periostin gene expression is also induced in chick AV cushion cultures by TGFβ3-treatment (Norris et al. 2009). Periostin is specifically found in cardiac cushion mesenchyme of developing mouse embryos and valve interstitial cells in adult mice as well as adult myocardial tissue (Kruzynska-Frejtag et al. 2001;Snider et al. 2008;Conway and Molkentin 2008;Teekakirikul et al. 2010). Periostin deficiency in mice leads to valvular defects (Norris et al. 2008;Snider et al. 2008). Normal adult human valves have a well defined tissue organization of the ECM: elastin-enriched atrialis in mitral and tricuspid valves or ventricularis in semilunar valves, glycosaminoglycans proteoglycans-enriched spongiosa, and collagen-enriched fibrosa (Wirrig and Yutzey 2011). In valve disease this ECM organization is disrupted, which includes fragmented collagen and excess accumulation of proteoglycans (Lucas, Jr. and Edwards 1982;Tamura et al. 1995;Grande-Allen et al. 2003) (Hinton and Yutzey 2011). Interestingly, this well-structured ECM organization gets disrupted by a complete deficiency of periostin in adult mice (Snider et al. 2008). In addition to an important role in maintaining valve structure, periostin also suppresses the unwanted presence of various non-valvular cell-lineages (i.e., cardiomyocyte-, smooth muscle-, and cartilage-like cells) in valves (Norris et al. 2008;Snider et al. 2008).

Striking resemblance in the gene expression patterns of periostin and Tgfb2 is found in the developing heart (Table 1) (Kruzynska-Frejtag et al. 2001;Snider et al. 2008;Molin et al. 2003;Azhar et al. 2003). Notably, deficiency of TGFβ2 or periostin results in defective mesenchymal differentiation during valve remodeling process (Azhar et al. 2011;Norris et al. 2008;Snider et al. 2008). Lack of periostin has been suggested to causes derepression of the osteogenic potential of mesenchymal cells, calcium deposition, and calcific aortic valve disease in mice (Markwald et al. 2010). Consistently, reduced levels of periostin are correlated with valve disease in pediatric patients (Snider et al. 2008). A recent study has provided another in vivo correlation between TGFβ and periostin in adult mouse model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Teekakirikul et al. 2010). Both TGFβ signaling and periostin levels are elevated in non-myocyte cells of this mouse model of hypertrophic growth. Surprisingly, administration of TGFβ-neutralizing antibodies has attenuated cardiac fibrosis, reduced periostin expression, and diminished non-myocyte proliferation in this mouse model. Collectively, periostin may be an important mediator and target of TGFβ signaling during heart development and in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, determination of the genetic regulation of periostin by specific TGFβ ligands in vivo during heart development and heart disease will lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of adult cardiovascular diseases and repair processes.

Integrated signaling network of TGFβ, Ang II, and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in cardiovascular diseases

It has recently become evident that there is a interrelationship of TGFβ, Ang II and mitogenactivated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways that plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular tissue repair (Fig. 1) (Lim and Zhu 2006;Rosenkranz 2004;Akat et al. 2009) (Lindsay and Dietz 2011). Ang II is the main active peptide of the renin-angiotensin system and acts through G-protein coupled receptors (Kumar et al. 2008). Two main Ang II receptor subtypes, AT1R and AT2R, have been identified through selective affinity for peptide and nonpeptide reagents. The type I receptor (1a) or (AT1a) knockout mice are hypotensive and appear to have a central nephrogenic mechanism contributing to the phenotype (Li et al. 2009). Two independent AT2R-deficient lines were created on different genetic backgrounds (reviewed in (Johren et al. 2004)). Both have increased basal blood pressure likely due to elevated AT1R expression in the absence of AT2R. Although both AT2R-deficient strains live into adulthood, they are susceptible to cardiac rupture after myocardial infarction. Many studies have indicated opposite function of AT1 and AT2 receptors in the cardiovascular system (Jones et al. 2004). AT2R-deficient mice have reduced cardiac fibrosis following pressure overload or Ang II-induced hypertension supporting a role for AT2R in cardiac remodeling. AT2R appears to function separately from AT1R which regulates adult cardiovascular function, fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. AT2R is upregulated in response to pathophysiological conditions including myocardial infarction suggesting that AT2R is involved in tissue remodeling, EMT, and fibrosis (Johren et al. 2004).

It has been well documented that both TGFβs and Ang II can induce MAPK signaling (Fig. 1) (Moustakas and Heldin 2009;Lee et al. 2007;Ulmasov et al. 2009;Rodriguez-Vita et al. 2005). The role of MAPKs in cardiovascular development and cardiovascular diseases has been extensively reviewed (Craig et al. 2008;Kehat and Molkentin 2010). Briefly, an upstream mitogen or growth factor signal initiates a module of three kinases: a MAPKKK that phosphorylates and activates a MAPKK (e.g., MEK) and finally activation of MAPK (e.g., ERK). MAPKs are critical effectors that regulate extracellular stimuli into cellular responses, such as differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis, all of which function during cardiovascular development, disease pathogenesis and tissue repair. There are 21 characterized MAP3Ks that activate known MAP2Ks, and they function in many aspects of cardiovascular biology. MAPKs function in sequential transduction of protein kinase cascades (Garrington and Johnson 1999). We have identified the MEKK3 and MEKK4 as important MAPKs which are involved in heart development (Stevens et al. 2008;Stevens et al. 2006). Similar to the Fibrillin-1 connection with TGFβ activity, significant advances have been made in defining the integration of ECM, especially hyaluronan, with growth factor pathways for normal cardiac EMT (Camenisch et al. 2000;Camenisch et al. 2002a). TGFβ2 activity is essential in mouse cardiac EMT (Camenisch et al. 2002b;Azhar et al. 2009a). It is also reported that MEKK3 is sufficient for the production of cardiac mesenchyme (Stevens et al. 2008); (Stevens et al. 2006). MEKK3 induction of TGFβ2 signaling drives cushion EMT and that it is consistent with cardiovascular defects in mice lacking MEKK3 (Yang et al. 2000). Collectively, these findings link downstream signaling effectors to ECM production and TGFβ pathways which both promote developmental EMT and valve maturation. Similarly, it is possible that MEKK3 along with ERKs, p38 and JNK1 are key nodal points in the TGFβ signaling network that drives cardiac remodeling in adult disease. There also appears to be selective expression of AT2R over AT1R in the embryonic heart with AT2R being ten-times more highly expressed in the embryonic heart than in the adult heart (Burrell et al. 2001). Additional evidence of the anatomical existence of the Ang II receptors in the brain areas that are critical for cardiovascular and fluid regulatory functions in utero has also been found (Hu et al. 2004). This is consistent with Ang II functioning early in cardiovascular development. Consistent with this observation, ACE inhibitors (ACEi) cause septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary valve stenosis during the first trimester (Cooper et al. 2006). This is highly significant considering the recent reporting of a 5% incidence of congenital heart disease (Pierpont et al. 2007). Although the molecular mechanism is unknown, this suggests a previously unrecognized role for TGFβ, Ang II and MAPK signaling in cardiac morphogenesis.

With regard to the involvement of TGFβ, Ang II and MAPKs in cardiovascular pathologies, it has been shown that ERKs and SMAD2 are activated in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome and that blocking TGFβ signaling inhibits both SMAD2 and ERK signaling (Holm et al. 2011). Inactivation of the AT2R gene results in increased aortic aneurysm in these mice (Habashi et al. 2011). Losartan (AT1R blocker) but not ACEi (blocks both AT1R & AT2R) abrogates this aneurysm progression in the combined mice. Both AT1R and ACEi attenuate canonical TGFβ signaling in the aorta, but losartan, which targets AT1R and not AT2R, specifically blocks activation of ERKs. This suggests a detrimental role for AT1R and a protective role for AT2R in the pathogenesis of aortic disease. The role of non-canonical TGFβ signaling has caught significant attention in adult cardiovascular pathology. Particularly, it has been well documented that TGFβ ligands can induce signaling through non-canonical or SMAD-independent pathways, including the MAPK and JNK1 pathways (Lee et al. 2007;Yamashita et al. 2008;Moustakas and Heldin 2009). With regard to the interrelationship of TGFβ, AngII and MAPK pathways, it is noteworthy that the Ang II signaling through AT1R has been shown to increase the expression of TGFβ ligands, receptors and activators, SMAD and MAPK signaling (Fig. 1) (Habashi et al. 2006;Akishita et al. 1999). Importantly, Ang II can activate the intracellular SMAD pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells, in a TGFβ-independent fashion, via the p38 MAPK pathway (Rodriguez-Vita et al. 2005). Ang II-infusion causes cardiac fibrosis and it also induces periostin expression in cardiac fibroblasts through a p38 MAPK-dependent pathway. Moreover, Ang II can induce TGFβ1 gene expression, SMAD activation, and periostin expression through the ERK1/2 pathway (Li et al. 2011). In another recent study it has been demonstrated that AT1R stimulation drives ERK1/2 activation; whereas, AT2R stimulation inhibits it in vivo in mouse aortic tissue. Furthermore, losartan attenuates ERK1/2 activation by blocking the AT1R cascade while simultaneously shunting signaling through the AT2R (Habashi et al. 2011). In summary, these findings are consistent with an integrated signaling network of TGFβ, Ang II and MAPK regulatory pathways in cardiovascular homeostatic, repair and stress response processes, as well as in cardiac function.

TGFβ-based therapies and its potential complications for cardiovascular repair

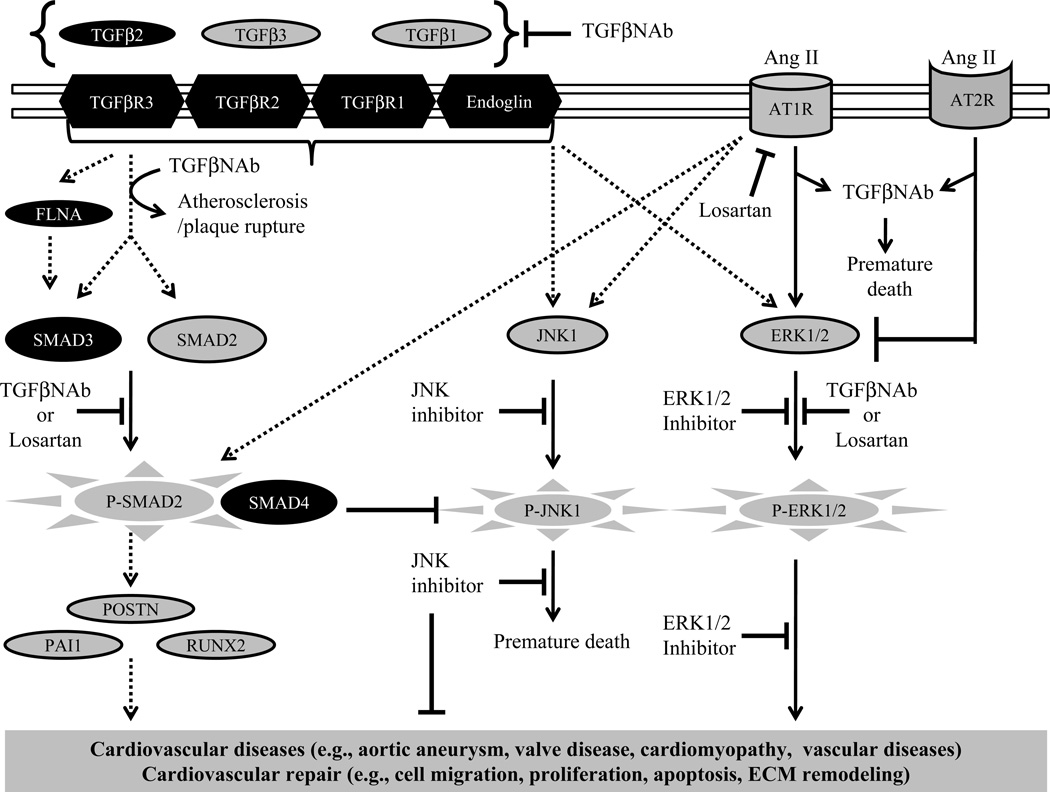

The hope for therapeutic targeting of TGFβ is clear when one looks at the number of cardiovascular and related diseases in which it is implicated. The concern is that because of the complexity of TGFβ signaling as indicated by unique and overlapping gene expression of TGFβ ligands and its integration with numerous other signaling pathways, targeting one TGFβ pathway could trigger severe unintended effects through other TGFβ pathways (Fig. 3). With respect to therapeutic approaches, systemic delivery of pan-TGFβ neutralizing antibodies (TGFβNAb), which non-specifically bind to all three TGFβ ligands, prevents aortic aneurysm (Habashi et al. 2006), developmental emphysema (Neptune et al. 2003), skeletal myopathy (Cohn et al. 2007), and mitral valve prolapse (Ng et al. 2004) in the Marfan syndrome mouse model. These therapeutic effects were reproduced by losartan, which also non-specifically inhibits TGFβ ligand expression, receptors, and activators such as thrombospondin and matrix metalloproteinases (Habashi et al. 2006). Similar studies have treated the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cardiac hypertrophy mouse model by pan-TGFβ antibodies and losartan. Both of these treatments were effective in preemptively blocking the cardiomyopathy in this model (Teekakirikul et al. 2010). Increased TGFβ signaling is also associated with elastic fiber disruption and hypertension phenotypes in Emillin-1-deficient mice. Heterozygous deletion of Tgfb1 has effectively rescued both elastic fiber defects and hypertension in these mice (Zacchigna et al. 2006). Since these studies suggest that reducing TGFβ signaling is a possible effective therapy for cardiovascular diseases, a multicenter clinical trial is currently underway to treat aneurysmal patients with Marfan syndrome (Lacro et al. 2007;Brooke et al. 2008).

Fig. 3.

Integrated signaling of TGFβ, Ang II, and MAPK pathways in cardiovascular diseases of elderly patients. The proposed model summarizes the published information about the TGFβ-based therapies and their potential complications for cardiovascular disease-treatment and repair. Black color highlights genes that are found mutated in patients of cardiovascular diseases. Induction or inhibition arrows in solid line indicate the presence of sufficient experimental evidence to support their involvement in cardiovascular disease. The dotted line arrows indicate that there is no direct evidence as yet available and that these require serious investigation.

Many studies have raised concerns about therapies that non-specifically target the TGFβ signaling as an attempt to treat cardiovascular diseases (Fig. 3). Unexpectedly, a partial genetic reduction of Smad4 in the Marfan syndrome mouse model causes exacerbation of aortic aneurysm and dissection and premature death of the Marfan mice (Holm et al. 2011). Surprisingly, a dramatic rise in JNK1 levels, which are normal in aortic tissue of the Marfan mice, is associated with this premature death in the combined heterozygous Smad4 Marfan mice. Interestingly, a JNK1 antagonist blocks aortic aneurysm in the Marfan mice that have reduced or fully retained Smad4, suggesting that the JNK1 pathway is a major player in the pathogenesis of aneurysm in Marfan mice. Since SMAD4 is co-SMAD molecule for both TGFβ and BMP signaling, the direct role of TGFβ signaling in the regulation of JNK1 signaling in the Marfan mouse model remains unclear. Similarly, strategies that would target SMAD4 may also be detrimental for overall health since conditional tissue-specific deletion of Smad4 has revealed its important role in cardiac development and cardiac hypertrophy, and cancer (Azhar et al. 2010;Nie et al. 2008;Yang and Yang 2010;Wang et al. 2005) (Song et al. 2011;Kim et al. 2006). Collectively, the concerns about the undesirable outcome of non-specific targeting of TGFβ pathway molecules may be valid, and a better knowledge of the function of TGFβ ligands, receptors and effectors in the adult cardiovascular system is an essential prerequisite before embarking on any TGFβ-based therapy to treat cardiovascular diseases.

Remarkably, TGFβNAb antibodies that neutralize TGFβ1/2/3 rescue the mitral valve (MV) prolapse, aortic aneurysm and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mouse models (Ng et al. 2004;Habashi et al. 2006;Teekakirikul et al. 2010). However, the same TGFβNAb antibody treatment induced lethal cardiovascular pathologies in mouse models of aneurysm and atherosclerosis (Wang et al. 2010;Mallat et al. 2001). Furthermore, reduced TGFβ signaling is found in progressive valve disease in genetic mouse models, which should caution against any uncontrolled reduction in TGFβ signaling as a therapeutic measure (Hinton et al. 2010;Snider et al. 2008). Numerous cardiovascular developmental malformations are reported in mice with disrupted TGFβ ligands signaling (Choudhary et al. 2009;Jiao et al. 2006;Wang et al. 2006) (Azhar et al. 2009a;Azhar et al. 2011;Azhar et al. 2010). Briefly, secondary effects on skeleton, bone repair, eyes, hearing and wound healing could occur from reducing TGFβ2 signaling (Sanford et al. 1997;Saika et al. 2001;Paradies et al. 1998;Crowe et al. 2000). TGFβ1 is a potent anti-inflammatory molecule in mice (Shull et al. 1992;Bommireddy and Doetschman 2007). It protects against Ang II-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Schultz et al. 2002); however, preemptive blocking of TGFβ ligands in an Ang II-induced mouse model leads to premature death caused by accelerated aortic dissection and rupture (Wang et al. 2010). Gene targeted disruption of latent TGFβ-binding proteins, which are critical for TGFβ activation, also causes cardiovascular as well as other developmental abnormalities and cancer (Todorovic et al. 2011;Yoshinaga et al. 2008). A recent study has identified genetic mutations in GATA4 that are associated with the AV septal defects in humans (Moskowitz et al. 2011). It turns out that these mutations in GATA4 disable GATA4 interaction with SMAD4. Endocardial Smad4 conditional knockout embryos develop severe defects in AV cushion formation and septation, and heterozygous Smad4 deletion causes AV septation defects in GATA4-deficient mice (Song et al. 2011;Moskowitz et al. 2011). Together, these studies highlight a beneficial role of TGFβ and/or BMP signaling in cardiovascular development. In another study it has been found that transaortic constriction of Smad3−/− mice causes cardiac hypertrophy (detrimental effect) and reduced fibrosis (beneficial effect) (Divakaran et al. 2009). Finally, increased TGFβ signaling is found to be associated with the cardiovascular complications in the experimental mouse model of Kawasaki disease. Unexpectedly, non-specific blocking of TGFβ by administration of TGFβNAb worsens the cardiovascular disease in these mice. This detrimental effect is attributed to a reduction in the proteolytic inhibitor and TGFβ target molecule, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI1), and an associated increase in matrix metalloproteinase activity (Alvira et al. 2011). It is noteworthy that many detrimental effects of TGFβ-based therapy can be attributed, in major part, to the role of TGFβ signaling in autoimmunity (Fig. 3) (Yoshimura et al. 2010;Shull et al. 1992;Azhar et al. 2009b;Anuurad et al. 2011;Alvira et al. 2011;King et al. 2009;Tieu et al. 2009;Daugherty et al. 2010;Wang et al. 2010;Mallat et al. 2001). Consequently, although targeting TGFβ ligands and their signaling offers hope for treating valve, aortic and myocardial and inflammatory cardiovascular complications in both syndromic and non-syndromic patients, serious concerns remain whether a non-specific preemptive blocking of TGFβ ligands aimed to treat a single cardiovascular manifestation could result in undesirable side-effects on other aspects of cardiovascular remodeling or physiology.

Perspectives

Current medical and surgical advances are likely to increase the number of elderly persons with cardiovascular disease in future. Clinical trials enrolling elderly patients are limited. Drug-based and/or less invasive strategies are better options to treat elderly patients. Numerous published studies indicate that TGFβ and its associated signaling pathways are highly significant effectors of cardiovascular development, function and pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, in adult cardiovascular tissues in which first-time repair or revision is required, the response of the tissue to surgical intervention is most likely going to involve TGFβ signaling pathways. These pathways must be understood so that the long-term response to surgical repair can be predicted and so that TGFβ-based therapies can be developed for more selective targets and with a better understanding of potential complications. Thus, it is important to determine the mechanisms by which TGFβ and its effector genes develop functional cardiovascular structures during development, and to maintain those functions during aging, under normal,stress and repair conditions. Genetic manipulation of the TGFβ pathway genes discussed above will reveal these mechanisms. In particular, the response of heterozygous genetic mouse models encoding mutated TGFβ pathway genes to the stresses of hypertension, exercise and age will be highly useful. Cardiovascular stress through transaortic constriction, exercise and aging and tissue transplantation through surgical advances such as artery by-pass or grafting in the context of these genetic manipulations will identify the stress and repair response mechanisms affected by these genes.

Serious concerns are emerging with respect to TGFβ-based therapies for cardiovascular diseases. It is therefore imperative that we develop a better understanding of the complexities of TGFβ signaling in the cardiovascular system during both embryonic development and aging so that highly specific, context-dependent, targeted therapies can provide the desired effects without complication. Finally, there is no solid evidence that establishes a direct cause-and-effect relationship between the TGFβ pathway genes and the disease process during aging. Most studies highlighting the involvement of ECM disruption on increased TGFβ signaling in vivo in disease pathogenesis are correlative. In fact, numerous studies based on direct mutation of TGFβ pathway genes in mouse indicate that TGFβ signaling is critical for both cardiovascular development and function. Thus, delineating TGFβ signaling networks involved in specific aspects of cardiovascular development and cardiovascular structure and function during the aging process should inform novel therapeutic approaches with higher specificity and more limited side effects. For example, instead of targeting TGFβ signaling in general for treatment of cardiovascular disease in patients, blocking ERKs and JNK1, which work well for the treatment of aortic aneurysm in Marfan mice, are other possible avenues that should be further explored in mouse models of other cardiovascular diseases. Finally, the projection that TGFβ signaling inhibition is the holy grail for cardiovascular diseases seems premature and has been perhaps overstated. Overall, therapeutic approaches to non-specifically reduce TGFβ signaling, applied in those with various mouse models, are unlikely to be beneficial and could be harmful in elderly patients. Because of the critical importance of TGFβ signaling in cardiovascular development and disease, an improved understanding of TGFβ pathway genes under whole animal settings (both conditional overexpression and deletion models) in longitudinal study, and the effects of TGFβ-based therapeutics under those settings, will by necessity have a high impact on the positive and negative consequences of TGFβ-based therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in parts, by funds from the National Institutes of Health Grants - HL070174, HL92508, HL085708, HL077493, HL82851-03, and HL105280. Additional funding was provided by Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (ABRC #0901) and The Stephen Michael Schneider/The William J. "Billy" Gieszl Award.

List of abbreviations

- MFS

Marfan syndrome

- EDS

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- ATS

Arterial Tortuosity syndrome

- LDS

Loeys-Dietz syndrome

- AOS

Aortic aneurysms and dissections with early-onset osteoarthritis

- ARVC/D or ARVD1

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia

- XMVD

X-linked myxomatous valvular dystrophy

- JPS

Juvenile polyposis syndrome

- HHT

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

- CCD

Cleidocranial dysplasia

- TGFβNAb

Pan-TGFβ neutralizing antibodies

- EMT

Epithelial mesenchymal transition

References

- Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik D, Lok VM, Jaffer FA, Aikawa M, Weissleder R. Multimodality molecular imaging identifies proteolytic and osteogenic activities in early aortic valve disease. Circulation. 2007;115:377–386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.654913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akat K, Borggrefe M, Kaden JJ. Aortic valve calcification: basic science to clinical practice. Heart. 2009;95:616–623. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.134783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst RJ, Lehnert SA, Faissner A, Duffie E. TGF beta in murine morphogenetic processes: the early embryo and cardiogenesis. Development. 1990;108:645–656. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akishita M, Ito M, Lehtonen JY, Daviet L, Dzau VJ, Horiuchi M. Expression of the AT2 receptor developmentally programs extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity and influences fetal vascular growth. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:63–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SM, Jackson KJ, Bushnell KM, McGuire PG. Spatial and temporal expression of the 72-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-2) correlates with development and differentiation of valves in the embryonic avian heart. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:261–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199707)209:3<261::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvira CM, Guignabert C, Kim YM, Chen C, Wang L, Duong TT, Yeung RS, Li DY, Rabinovitch M. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta worsens elastin degradation in a murine model of Kawasaki disease. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1210–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrabi S, Bekheirnia MR, Robbins-Furman P, Lewis RA, Prior TW, Potocki L. SMAD4 mutation segregating in a family with juvenile polyposis, aortopathy, and mitral valve dysfunction. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1165–1169. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anuurad E, Enkhmaa B, Gungor Z, Zhang W, Tracy RP, Pearson TA, Kim K, Berglund L. Age as a Modulator of Inflammatory Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur HM, Bamforth SD. TGFbeta signaling and congenital heart disease: Insights from mouse studies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;10 doi: 10.1002/bdra.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur HM, Ure J, Smith AJ, Renforth G, Wilson DI, Torsney E, Charlton R, Parums DV, Jowett T, Marchuk DA, Burn J, Diamond AG. Endoglin, an ancillary TGFbeta receptor, is required for extraembryonic angiogenesis and plays a key role in heart development. Dev Biol. 2000;217:42–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M, Brown K, Gard C, Chen H, Rajan S, Elliott DA, Stevens MV, Camenisch TD, Conway SJ, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor Beta2 is required for valve remodeling during heart development. Dev Dyn. 2011;10 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M, Runyan RB, Gard C, Sanford LP, Miller ML, Andringa A, Pawlowski S, Rajan S, Doetschman T. Ligand-specific function of transforming growth factor beta in epithelial-mesenchymal transition in heart development. Dev Dyn. 2009a;238:431–442. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21854. PMC2805850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M, Schultz JE, Grupp I, Dorn GW, Meneton P, Molin DG, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor beta in cardiovascular development and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:391–407. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M, Wang PY, Frugier T, Koishi K, Deng C, Noakes PG, McLennan IS. Myocardial deletion of Smad4 using a novel alpha skeletal muscle actin Cre recombinase transgenic mouse causes misalignment of the cardiac outflow tract. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:546–555. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M, Yin M, Bommireddy R, Duffy JJ, Yang J, Pawlowski SA, Boivin GP, Engle SJ, Sanford LP, Grisham C, Singh RR, Babcock GF, Doetschman T. Generation of mice with a conditional allele for transforming growth factor beta 1 gene. Genesis. 2009b;47:423–431. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara NP, Wrana JL, Letarte M. Endoglin is an accessory protein that interacts with the signaling receptor complex of multiple members of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:584–594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard JA, Lyons RM, Moses HL. The cell biology of transforming growth factor beta. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1032:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(90)90013-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JV, Desgrosellier JS. Early events in valvulogenesis: a signaling perspective. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:58–72. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram U, Molin DG, Wisse LJ, Mohamad A, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Speer CP, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de GA. Double-outlet right ventricle and overriding tricuspid valve reflect disturbances of looping, myocardialization, endocardial cushion differentiation, and apoptosis in Tgfb2 knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;103:2745–2752. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.22.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beffagna G, Occhi G, Nava A, Vitiello L, Ditadi A, Basso C, Bauce B, Carraro G, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Danieli GA, Rampazzo A. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-beta3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharathy S, Xie W, Yingling JM, Reiss M. Cancer-associated transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene mutant causes activation of bone morphogenic protein-Smads and invasive phenotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1656–1666. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommireddy R, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor-beta: From its effect in T cell activation to a role in dominant tolerance. In: Graca Luis., editor. The Immune Synapse as a Novel Target for Therapy. Basel: Birkhauser Verlag; 2007. pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bonyadi M, Rusholme SA, Cousins FM, Su HC, Biron CA, Farrall M, Akhurst RJ. Mapping of a major genetic modifier of embryonic lethality in TGF beta 1 knockout mice. Nat Genet. 1997;15:207–211. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke BS, Habashi JP, Judge DP, Patel N, Loeys B, Dietz HC., III Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2787–2795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Boyer AS, Runyan RB, Barnett JV. Requirement of type III TGF-beta receptor for endocardial cell transformation in the heart. Science. 1999;283:2080–2082. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell JH, Hegarty BD, McMullen JR, Lumbers ER. Effects of gestation on ovine fetal and maternal angiotensin receptor subtypes in the heart and major blood vessels. Exp Physiol. 2001;86:71–82. doi: 10.1113/eph8602075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caira FC, Stock SR, Gleason TG, McGee EC, Huang J, Bonow RO, Spelsberg TC, McCarthy PM, Rahimtoola SH, Rajamannan NM. Human degenerative valve disease is associated with up-regulation of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 receptor-mediated bone formation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1707–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, Molin DG, Person A, Runyan RB, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, McDonald JA, Klewer SE. Temporal and Distinct TGFbeta Ligand Requirements during Mouse and Avian Endocardial Cushion Morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2002b;248:170–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, Runyan RB, Markwald RR. Molecular regulation of cushion morphogenesis. In: Harvey R, Rosenthal N, editors. Heart Development and Regeneration. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 363–388. [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, Schroeder JA, Bradley J, Klewer SE, McDonald JA. Heart-valve mesenchyme formation is dependent on hyaluronan-augmented activation of ErbB2–ErbB3 receptors. Nat Med. 2002a;8:850–855. doi: 10.1038/nm742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, Spicer AP, Brehm-Gibson T, Biesterfeldt J, Augustine ML, Calabro AJ, Kubalak S, Klewer SE, McDonald JA. Disruption of hyaluronan synthase-2 abrogates normal cardiac morphogenesis and hyaluronan-mediated transformation of epithelium to mesenchyme. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:349–360. doi: 10.1172/JCI10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Combs MD, Yutzey KE. Transcriptional regulation of heart valve progenitor cells. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010a;31:414–421. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9616-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Wirrig EE, Hinton RB, Merrill WH, Spicer DB, Yutzey KE. Twist1 promotes heart valve cell proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression during development in vivo and is expressed in human diseased aortic valves. Dev Biol. 2010b doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary B, Zhou J, Li P, Thomas S, Kaartinen V, Sucov HM. Absence of TGFbeta signaling in embryonic vascular smooth muscle leads to reduced lysyl oxidase expression, impaired elastogenesis, and aneurysm. Genesis. 2009;47:115–121. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Greuel JN, Connolly JM, Sorichillo E, Narula NR, Rapoport HS, Mohler ER, III, Gorman JH, III, Gorman RC, Levy RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta1 mechanisms in aortic valve calcification: increased alkaline phosphatase and related events. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn RD, van Erp C, Habashi JP, Soleimani AA, Klein EC, Lisi MT, Gamradt M, ap Rhys CM, Holm TM, Loeys BL, Ramirez F, Judge DP, Ward CW, Dietz HC. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGF-beta-induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nat Med. 2007;13:204–210. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton LA, Potash DA, Brown CB, Barnett JV. Coronary vessel development is dependent on the type III transforming growth factor beta receptor. Circ Res. 2007;101:784–791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway SJ, Molkentin JD. Periostin as a heterofunctional regulator of cardiac development and disease. Curr Genomics. 2008;9:548–555. doi: 10.2174/138920208786847917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, Dudley JA, Dyer S, Gideon PS, Hall K, Ray WA. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2443–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coucke PJ, Willaert A, Wessels MW, Callewaert B, Zoppi N, De Backer J, Fox JE, Mancini GM, Kambouris M, Gardella R, Facchetti F, Willems PJ, Forsyth R, Dietz HC, Barlati S, Colombi M, Loeys B, De Paepe A. Mutations in the facilitative glucose transporteRGLUT10 alter angiogenesis and cause arterial tortuosity syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:452–457. doi: 10.1038/ng1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig EA, Stevens MV, Vaillancourt RR, Camenisch TD. MAP3Ks as central regulators of cell fate during development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3102–3114. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe MJ, Doetschman T, Greenhalgh DG. Delayed wound healing in immunodeficient TGF-beta1 knockout mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly AC, Randall RA, Hill CS. Transforming growth factor beta-induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation in epithelial cells is mediated by novel receptor complexes and is essential for anchorage-independent growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6889–6902. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01192-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das BB, Taylor AL, Yetman AT. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in children and young adults with Marfan syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2006;27:256–258. doi: 10.1007/s00246-005-1139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Charo IF, Owens Iii AP, Howatt DA, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II infusion promotes ascending aortic aneurysms: attenuation by CCR2 deficiency in apoE −/− mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010 doi: 10.1042/CS20090372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer J. Cardiovascular characteristics in Marfan syndrome and their relation to the genotype. Verh K Acad Geneeskd Belg. 2009b;71:335–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer J. The expanding cardiovascular phenotype of Marfan syndrome. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009a;10:213–215. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit MC, de Coo IF, Lequin MH, Halley DJ, Roos-Hesselink JW, Mancini GM. Combined cardiological and neurological abnormalities due to filamin A gene mutation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0206-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Akhurst RJ. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-beta family proteins in development and disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/ncb434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson MC, Martin JS, Cousins FM, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, Akhurst RJ. Defective haematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1 knock out mice. Development. 1995;121:1845–1854. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson MC, Slager HG, Duffie E, Mummery CL, Akhurst RJ. RNA and protein localisations of TGF beta 2 in the early mouse embryo suggest an involvement in cardiac development. Development. 1993;117:625–639. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz HC. TGF-beta in the pathogenesis and prevention of disease: a matter of aneurysmic proportions. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:403–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI42014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divakaran V, Adrogue J, Ishiyama M, Entman ML, Haudek S, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. Adaptive and maladptive effects of SMAD3 signaling in the adult heart after hemodynamic pressure overloading. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:633–642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.823070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetschman T. Interpretation of phenotype in genetically engineered mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1999;49:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker N, Krieglstein K. Targeted mutations of transforming growth factor-beta genes reveal important roles in mouse development and adult homeostasis. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6982–6988. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]