Abstract

It has been proposed recently that the type of genetic instability in cancer cells reflects the selection pressures exerted by specific carcinogens. We have tested this hypothesis by treating immortal, genetically stable human cells with representative carcinogens. We found that cells resistant to the bulky-adduct-forming agent 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) exhibited a chromosomal instability (CIN), whereas cells resistant to the methylating agent N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) exhibited a microsatellite instability (MIN) associated with mismatch repair defects. Conversely, we found that cells purposely made into CIN cells are resistant to PhIP, whereas MIN cells are resistant to MNNG. These data demonstrate that exposure to specific carcinogens can indeed select for tumor cells with distinct forms of genetic instability and vice versa.

Genetic instability and chemical carcinogens represent two central themes of modern cancer research. It appears that most, if not all, human cancers are genetically unstable, and that there are several distinct types of instabilities. It is also widely accepted that endogenous or exogenous mutagens contribute to most human cancers. But how are these two themes related? Breivik and Gaudernack (1) have recently proposed that the type of instability in cancers may reflect the selection pressures exerted by specific carcinogens. In particular, they predicted that cells exposed to bulky-adduct-forming agents will develop a chromosome instability (CIN), whereas cells exposed to methylating agents should develop a mismatch repair (MMR) defect and consequent microsatellite instability (MIN).

Colorectal cancers (CRCs) provide an excellent system to examine the relationship between carcinogens and genetic instability (2). Dietary carcinogens are thought to play a major role in colorectal tumorigenesis (3, 4), and most CRCs manifest either CIN or MIN but not both (5). To evaluate whether specific carcinogens could cause specific forms of instability, we used a CRC line (H3) that was immortal but completely stable in terms of both maintenance of chromosome number (6) and nucleotide sequence (7). This line was derived from a MIN primary cancer with a mutation of the hMLH1 MMR gene (8). A chromosome 3 (containing the wild-type hMLH1 gene) was transferred into this line, rendering it MMR proficient (7). To test whether carcinogen exposure could select for cells with different forms of instability, we treated these cells with either 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) or N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG). PhIP is the most abundant heterocyclic amine in typical Western diets, and is found in well done cooked beef and chicken (9–11). PhIP has been shown to cause a variety of cancers in experimental animals and is representative of bulky-adduct-forming agents (12–15). MNNG represents a standard alkylating agent that preferentially methylates the O6 position of deoxyguanosine residues in DNA and also is a potent carcinogen in rodent models (16). There is much epidemiological evidence indicating the relevance of these two compounds to human cancer (4, 17–20).

Methods

Cell Culture.

HCT116 and DLD1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. HCT116 cells complemented with chromosome 3 (H3) were a generous gift of R. Boland (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla) and have been described elsewhere (7). Cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (HyClone), 100 units/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin.

Carcinogen Treatment.

For treatment with PhIP (Toronto Research Chemicals, Downsview, ON, Canada) and with MNNG (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI), cells were detached, centrifuged, counted, and resuspended in serum-free RPMI medium 1640 (Life Technologies). PhIP was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and activated in serum-free RPMI medium 1640 containing 0.4 mg/ml Aroclor 1254-induced S9 rat liver extracts (Moltox, Boone, NC), 0.23 mM NADP, 0.28 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 0.45 mM MgCl2, 0.45 mM KCl, and 200 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5). Cells were treated 2–4 h at 37°C. After treatment, the cells were resuspended in complete McCoy's 5A medium and reseeded. PhIP- and MNNG-resistant cell lines were established by two successive treatments with 50 μM PhIP or with 5 μM MNNG and 25 μM O6-benzylguanine. Between 10−5 and 10−6 of the parental cells survived treatments with either regimen. The treatment was repeated after cells surviving the first round of treatment had recovered exponential growth, and single-cell clones were obtained by limiting dilution.

Carcinogen Resistance.

The relative resistance of isolated clones was evaluated by treatment of 105 cells with appropriate concentrations of carcinogens. After exposure to drugs, cells were grown in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Costar) until colonies were visible (7–15 days), then washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution (Life Technologies) and stained with 2% (vol/vol) crystal violet in buffered formalin. Relative resistance of the treated cultures was normalized to the plating efficiency of the untreated controls.

Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH).

Methods for FISH analysis with chromosome-specific centromeric probes and quantitative analysis of chromosome loss rates have been described (6). In some experiments, two hybridization probes were applied, one hybridizing to the centromere of chromosome 12 (labeled with biotin, detected with fluorescein) and the other to the distal part of chromosome 12q (labeled with digoxigenin, detected with tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate). The plasmid D12Z1 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The chromosome 12 BAC clones AC002375, AC002351, and AC002978 were obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). FISH analysis was restricted to cells that showed the same number of signals for both probes, thereby excluding cells that appeared to have lost a chromosome because one hybridization signal overlapped another. Clones were grown for 25 to 50 generations, and cells were analyzed with a Nikon E-800 fluorescence microscope. Pictures were acquired with a charge-coupled device camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) and the ip lab software program (Scanalytics, Billerica, MA). Most of the controls—MNNG-resistant and PhIP-resistant cells—were pseudodiploid, although a low fraction of tetraploid clones was observed after limiting dilution of cells of each of these phenotypes. The tetraploid clones behaved identically to the diploid clones of the same type with respect to MMR gene expression, drug resistance, and chromosomal stability.

Multiplex-FISH analysis of metaphase chromosome spreads was performed according to standard procedures.

Immunoblotting.

Cell lysates were prepared in Laemmli sample buffer. Immunoblotting was performed on Immobilon P membranes (Millipore). Anti-MLH1 antibody (PharMingen), and anti-MSH2 antibody were used according to the manufacturer's instructions or as described (21). Signals were developed by using the Renaissance Plus Enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (New England Nuclear).

hBUB1 Expression.

To generate BUB-DLD1 cells, a mutant hBUB1 gene found in a human cancer (C-to-A transversion at codon 392 in line V429; ref. 22) was inserted into the pBI-GFP-derived vector and transfected into DLD1 cells that were engineered to constitutively express a modified tTA transcriptional activator (DLD1-TET; ref. 23). Expression of mutant hBUB1 and green fluorescent protein (GFP) was repressed by 20 ng/ml doxycycline, and induction was obtained by growing cells in the presence of 0.33 ng/ml doxycycline. The level of expression of mutant hBUB1 transcripts induced by this treatment was very similar to the endogenous level of wild-type hBUB1, as assessed by reverse transcription–PCR and sequence analysis. GFP-DLD1 cells stably transfected with the pBI-GFP-derived vector without any hBUB1 gene served as a control.

Results

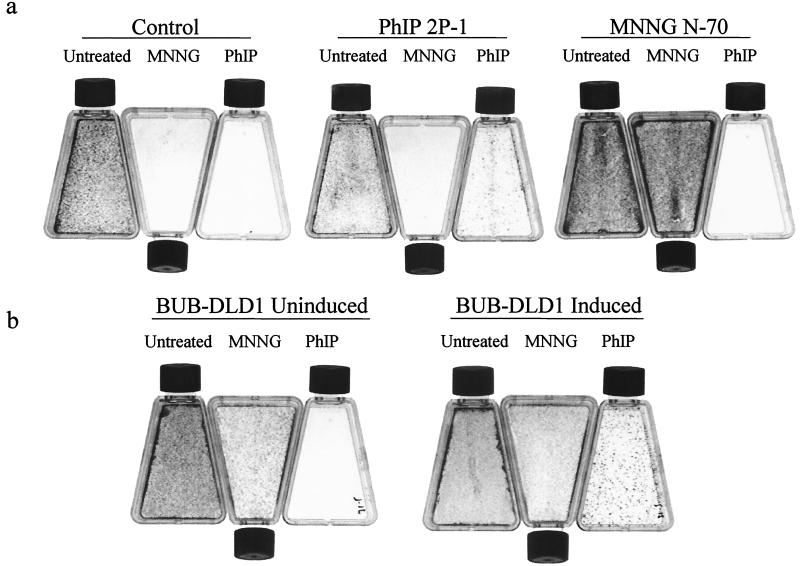

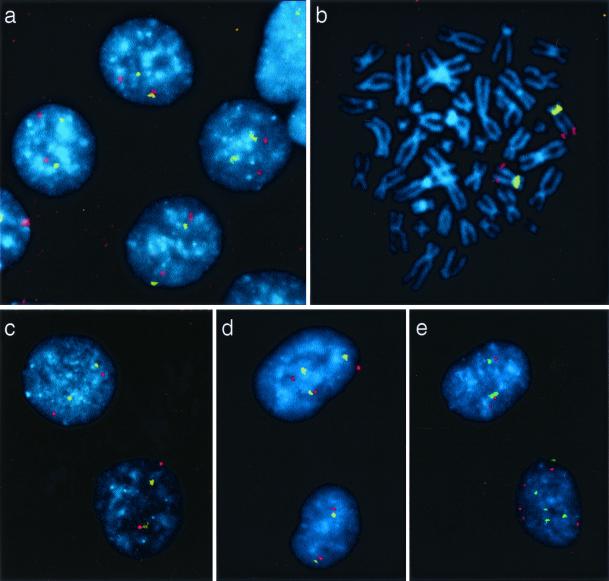

To test whether H3 cells could develop resistance to PhIP, we treated cells with activated PhIP at concentrations that killed most of the cells. The cells that survived this treatment were expanded as clones. Of 14 clones tested, 9 showed increased resistance to PhIP (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The other clones that survived treatment did not acquire a true carcinogenic resistance when reexposed, and were therefore not analyzed further. To determine whether the resistant cells exhibited chromosomal instability, we grew the clones for a defined number of generations and assessed chromosome losses and gains by using FISH (Fig. 2). We developed an improved method for performing such FISH analyses by including two hybridization probes in each experiment; one hybridized to the centromere of chromosome 12 (detected with fluorescein), and the other hybridized to the distal part of the long arm of chromosome 12 (detected with tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate). The dual signals from the same chromosome provided very high signal-to-noise ratios and an unambiguous determination of gains or losses of whole chromosome arms. By using this procedure, parental cells were found to be completely stable (Fig. 2a), with chromosome loss or gain rates that were identical to those found in normal lymphocytes (<10−3 losses or gains of chromosome 12 per generation; Table 1). In contrast, all nine PhIP-resistant clones exhibited striking degrees of CIN, averaging 10−2 losses or gains of chromosome 12 per generation (Fig. 2 d and e; Table 1). Similar degrees of CIN were found by using hybridization when probes from other chromosomes were used (data not shown). When extrapolated to the whole genome, this instability translates to the loss or gain of one chromosome for every five cell divisions. This degree of CIN was comparable to that observed in many CRC lines derived from primary tumors (6).

Figure 1.

Resistance to MNNG and PhIP. (a) Approximately 105 cells of control H3 clones (not previously exposed to carcinogens) or clones derived after exposure to carcinogens (see Table 1 for enumeration) were exposed to either 50 μM PhIP or 5 μM MNNG as described in Materials and Methods, and cells were stained with crystal violet 14 days later. Untreated cells served as a plating control (Untreated). (b) BUB-DLD1 cells, inducibly expressing a dominant mutant hBUB1 gene were exposed to PhIP or MNNG and stained as in a. As DLD1 cells are MMR deficient, they are resistant to MNNG, irrespective of induction.

Table 1.

Carcinogen-specific induction of genetic instability

| Clone name | Description | Parental cells | CIN,* % | PhlP† | MNNG† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3 | Parent culture | H3 | 3 | <1 | 1 |

| Control 8 | unselected control subclone | H3 | 1 | 2 | <1 |

| Control 14 | unselected control subclone | H3 | 3 | 4 | 2, 3 |

| Control 17 | unselected control subclone | H3 | 1 | 3 | <1 |

| P1 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 16 | 73, 63 | 60 |

| 2P1 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 42 | 44, 39, 47 | <1 |

| 2P2 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 33 | 49, 21 | 8 |

| 2P4 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 30 | 10 | 5, 6 |

| 2P7 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 12 | 21, 12 | 5 |

| P2 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 20 | 10 | 3 |

| P3 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 22 | 50 | <1, <1 |

| 2P9 | Cloned after treatment with PhlP | H3 | 25 | 45, 33 | 5, <1 |

| A6 | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 1 | 31 | 58 |

| 5N | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 5 | <1 | 37 |

| N68 | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 3 | 7 | 27 |

| N70 | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 2 | <1 | 62, 80 |

| N74 | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 5 | <1 | 42, 65 |

| A2 | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 10 | <1 | 70, 68 |

| A5 | Cloned after treatment with MNNG | H3 | 5 | 18 | 63 |

| GFP-DLD1, uninduced | no exogenous expression | DLD1-TET | 2 | <1 | ND |

| GFP-DLD1, induced | express GFP only | DLD1-TET | 1 | <1 | ND |

| BUB-DLD1, uninduced‡ | no exogenous expression | DLD1-TET | 4 | <1 | 51 |

| BUB-DLD1, induced‡ | express GFP + mutant hBUB1 | DLD1-TET | 34 | 17, 38 | 47 |

Representative clones derived from treatment with the indicated agents were studied for chromosomal instability (CIN) and resistance to carcinogens. H3 cells are an HCT116 derivative carrying an extra copy of chromosome 3 that contains the wild-type hMLH1 gene (7). DLD1-TET cells are a derivative of DLD1 cells that constitutively express tTA, a modified tet-based transcriptional activator (23).

Chromosomal instability was measured by FISH analysis, with the numbers indicating the fraction of cells whose chromosome 12 copy number was different from the modal number of the clone, analyzed 25 generations after single cell dilution. The modal number was 2 in the diploid clones and 4 in tetraploid clones (see Materials and Methods). Boldface numbers indicate values of CIN, % > 10.

The number of colonies arising after treatment of the indicated clones with PhlP or MNNG relative to the number of colonies arising in control flasks in the absence of treatment. ND, not determined.

GFP-DLD1 and BUB-DLD1 cells were derived from DLD1 cells engineered to inducibly express genes under the control of a tet operon. GFP-DLD1 cells inducibly express GFP, while BUB-DLD1 cells inducibly express a dominant mutant hBUB1 gene in addition to GFP. As DLD1 cells are MMR deficient, they are resistant to MNNG, irrespective of induction.

Figure 2.

FISH analysis of chromosomal instability in clones surviving carcinogen exposure. A chromosome 12-specific centromeric probe was labeled with FITC (yellow), and a contig of three bacterial artificial chromosome clones mapping to the distal part of chromosome 12q was labeled with tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (red). Cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Nuclei of control cells (a) and MNNG-resistant clones (b and c) exhibited two yellow and two red signals in virtually every nucleus (a and c) and metaphase spread (b). In contrast, cells of PhIP-resistant clones (d and e) often exhibited more or less than two copies of chromosome 12.

The underlying hypothesis for this study was that different mutagens should cause different forms of instability. Several previous experiments have demonstrated that alkylating agents can select for cells with MIN, a characteristic of MMR deficiency (24, 25). To test whether alkylating agents induce MIN in H3 cells, and to provide a control for PhIP, we treated H3 cells with MNNG. Of 15 clones that survived this treatment, 13 were resistant to MNNG, demonstrating that we had selected for cells that were intrinsically resistant to this compound (Table 1). Two of seven MNNG-resistant clones were resistant to PhIP, whereas one of ten PhIP-resistant clones was cross-resistant to MNNG. Cross-resistance to DNA-damaging agents has been previously observed in MMR-deficient cells (26).

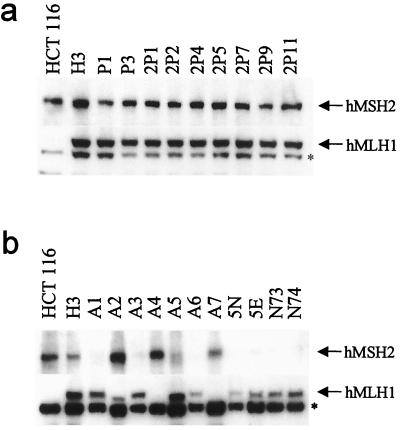

Western blots were then used to assess MMR gene expression in MNNG- and PhIP-resistant clones, focusing on expression of the two genes (hMLH1 and hMSH2) most commonly altered in MMR-deficient cells. All of the PhIP-resistant clones expressed hMLH1 and hMSH2 proteins of the expected sizes (Fig. 3a). In striking contrast, the MNNG-resistant clones were found to lack either full-length hMLH1 or hMSH2 proteins (Fig. 3b). Importantly, every MNNG-resistant clone expressed either full-length hMLH1 or hMSH2, but none expressed both, demonstrating a highly specific mechanism for the loss of MMR gene activity in each clone. Most human cancer cells with MIN similarly lack expression of one of the MMR genes (generally hMLH1; ref. 27). In contrast to the PhIP-resistant clones, none of the MNNG-resistant clones exhibited high levels of CIN when examined by FISH (Fig. 2 b and c; Table 1). To confirm and extend these studies, we employed Multiplex-FISH analysis to paint entire metaphase spreads. Analysis was restricted to near-diploid metaphases to eliminate possible errors caused by misinterpretation of tetraploid cells. Multiplex-FISH analysis confirmed an elevated rate of chromosomal loss in PhIP-resistant clones compared to MNNG-resistant clones (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Expression of hMLH1 and hMSH2 proteins in clones surviving carcinogen exposure. Western blotting was performed with anti-hMLH1 and anti-hMSH2 antibodies. H3 cells expressed full-length forms of both hMLH1 and hMSH2, as did every PhIP-resistant clone (a). In contrast, each MNNG-resistant clone expressed either a full-length hMSH2 or a full-length hMLH1 protein, but not both, demonstrating a highly specific mechanism for loss of MMR gene activity in each clone (b). The asterisk (*) indicates a nonspecific band crossreacting with the anti-hMLH1 antibody.

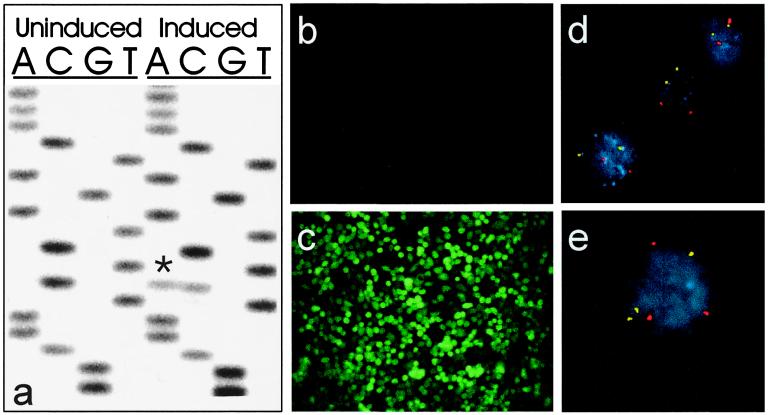

It is known that cells with MMR gene mutations are resistant to alkylating agents like MNNG (7). However, it was not known whether CIN cells were resistant to bulky-adduct-forming agents. To evaluate this issue, we sought to generate a CRC line rendered chromosomally unstable by inducibly expressing a dominant-negative mutant of the hBUB1 gene. Such mutant hBUB1 genes can disrupt the mitotic-spindle checkpoint and lead to aneuploidy (22). As H3 cells were not conducive to the establishment of an inducible expression system, we used another CRC line, DLD1, for these purposes. DLD1 is a MIN cell line and, as expected, displays resistance to MNNG (Table 1). Expression of the mutant hBUB1 gene in the engineered DLD1 cells, called “BUB-DLD1”, was repressed by tetracycline and could be induced by the removal of tetracycline (Fig. 4a). Coexpression of a GFP gene that was regulated by the same promoter as the mutant hBUB1 gene facilitated the analysis of these cells and ensured homogeneous expression patterns (Fig. 4 b and c). Uninduced BUB-DLD1 cells were found to be chromosomally stable (Fig. 4d; Table 1) but manifested CIN after induction of the mutant hBUB1 gene (Fig. 4e; Table 1). As expected from their CIN phenotype, the BUB-DLD1 cells were karyotypically aneuploid after induction of hBUB1 (data not shown). Finally, BUB-DLD1 cells exhibited increased resistance to PhIP only after induction of the hBUB1 gene (Table 1). The magnitude of resistance was similar to that observed in clones of H3 cells that were derived by exposure to PhIP (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Inducible expression of a mutant hBUB1 allele confers CIN. (a) Sequence of hBUB1 transcripts assessed by reverse transcription–PCR analysis of RNA from BUB-DLD1 cells. The exogenous mutant hBUB1 gene contained a C-to-A transversion at codon 492 (marked by *), resulting in a substitution of tyrosine for serine. Before induction, there was no mutant hBUB1 transcript detectable, whereas after induction, the level of mutant hBUB1 expression was similar to that of the endogenous wild-type hBUB1 gene. (b) Fluorescence microscopy showed no detectable expression of the coexpressed GFP gene before induction, but (c) uniform expression of GFP after induction. (e) Cells expressing mutant hBUB1 after induction were chromosomally unstable, as indicated by an abnormal number of FISH signals in a high fraction of cells, whereas uninduced cells (d) were stable. The red and yellow dots represent centromeric probes specific for chromosomes 7 and 12, respectively.

Discussion

We have shown that cells selected for resistance to different carcinogens have strikingly different forms of instability. Conversely, cells with naturally occurring MIN or engineered CIN are resistant to the drugs that can lead to selection for these phenotypes. The mechanisms underlying the resistance of MIN cells to alkylating agents are well known (28, 29), but the mechanisms underlying the development of CIN after exposure to PhIP are not yet clear. Bulky-adduct-forming agents like PhIP induce chromosome breaks through nucleotide excision–repair processes (30), leading to the suggestion that cells with defects in DNA repair or mitotic checkpoints might be selected after exposure to PhIP (1). We evaluated our PhIP-resistant clones for checkpoint defects after irradiation or microtubule disruption, but found none in standard assays (data not shown). Either more subtle forms of checkpoint defects are present in these clones, or other mechanisms are involved. The concordance between PhIP resistance and CIN, however, suggests a mechanistic link between these two phenotypes. Some of the MMR gene defects responsible for MIN were discovered through investigation of the genetic defects in cell lines resistant to MNNG (31). By analogy, the PhIP-resistant lines described here may provide critical clues to the nature of the genes that underlie CIN.

These results have obvious implications for the mechanisms underlying development of instability in human cancers. In the gastrointestinal tract, for example, cells are constantly exposed to carcinogens like PhIP and MNNG at concentrations determined by diet, genetic make-up, bacterial flora, and location of epithelial cells within the gastrointestinal tract. Abundant studies indicate that some gastrointestinal tumors, particularly those in the stomach and in the proximal large intestine, exhibit MIN, although others, particularly in the esophagus and distal large intestine, exhibit CIN (32–34). The experimental data reported here strongly support the hypothesis that carcinogen exposure determines the type of instability in these cancers. This hypothesis suggests that the different forms of instability evolve through selection pressures that can readily be understood in Darwinian terms (1, 35, 36) rather than arise in a random and mysterious manner. These data provide potential clues to one of the remaining unsolved problems in cancer research, namely, the relationship between dietary factors and the genetic abnormalities that drive tumorigenesis (1, 36).

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Morsberger (Cytogenetics Core) and Leslie Meszler (Cell Imaging Core Facility) for their excellent technical help. A.B. thanks Daria Abbate and Maddalena Bardelli for their constant support and encouragement. This work was supported by the Concern Foundation (to C.L.), the Clayton Fund, and National Institutes of Health Grants CA 43460 and CA 62924.

Abbreviations

- CIN

chromosome instability

- MIN

microsatellite instability

- MMR

mismatch repair

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- PhIP

2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine

- MNNG

N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

Footnotes

See commentary on page 5379.

References

- 1.Breivik J, Gaudernack G. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:245–254. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duesberg P, Stindl R, Hehlmann R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14295–14300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimura T. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:387–395. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser G E. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:532S–538S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.532s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lengauer C, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nature (London) 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lengauer C, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nature (London) 1997;386:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koi M, Umar A, Chauhan D P, Cherian S P, Carethers J M, Kunkel T A, Boland C R. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4308–4312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides N C, Wei Y F, Ruben S M, Carter K C, Rosen C A, Haseltine W A, Fleischmann R D, Fraser C M, Adams M D, et al. Science. 1994;263:1625–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.8128251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felton J S, Malfatti M A, Knize M G, Salmon C P, Hopmans E C, Wu R W. Mutat Res. 1997;376:37–41. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulp K S, Knize M G, Malfatti M A, Salmon C P, Felton J S. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2065–2072. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gooderham N J, Murray S, Lynch A M, Yadollahi-Farsani M, Zhao K, Rich K, Boobis A R, Davies D S. Mutat Res. 1997;376:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Layton D W, Bogen K T, Knize M G, Hatch F T, Johnson V M, Felton J S. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:39–52. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tudek B, Bird R P, Bruce W R. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1236–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirai T, Sano M, Tamano S, Takahashi S, Hirose M, Futakuchi M, Hasegawa R, Imaida K, Matsumoto K, Wakabayashi K, et al. Cancer Res. 1997;57:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghoshal A, Preisegger K H, Takayama S, Thorgeirsson S S, Snyderwine E G. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2429–2433. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.11.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimura T, Terada M. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:163–167. doi: 10.1093/jjco/28.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potter J D, Slattery M L, Bostick R M, Gapstur S M. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:499–545. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinha R, Kulldorff M, Swanson C A, Curtin J, Brownson R C, Alavanja M C. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3753–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Kok T M, van Maanen J M. Mutat Res. 2000;463:53–101. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bingham S A. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:243–248. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leach F S, Polyak K, Burrell M, Johnson K A, Hill D, Dunlop M G, Wyllie A H, Peltomaki P, Delachapelle A, Hamilton S R, et al. Cancer Res. 1996;56:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cahill D P, Lengauer C, Yu J, Riggins G J, Willson J K, Markowitz S D, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nature (London) 1998;392:300–303. doi: 10.1038/32688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang P M, Rago C, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14517–14522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Branch P, Aquilina G, Bignami M, Karran P. Nature (London) 1993;362:652–654. doi: 10.1038/362652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aebi S, Kurdi-Haidar B, Gordon R, Cenni B, Zheng H, Fink D, Christen R D, Boland C R, Koi M, Fishel R, Howell S B. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3087–3090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaab W E, Kort K L, Skopek T R. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4921–4925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman J G, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff J R, Ahuja N, Issa J P, Markowitz S, Willson J K, Hamilton S R, Kinzler K W, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bignami M, O'Driscoll M, Aquilina G, Karran P. Mutat Res. 2000;462:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiricny J. Mutat Res. 1998;409:107–121. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfau W, Martin F L, Cole K J, Venitt S, Phillips D H, Grover P L, Marquardt H. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:545–551. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides N C, Liu B, Parsons R, Lengauer C, Palombo F, Darrigo A, Markowitz S, Willson J K V, Kinzler K W, et al. Science. 1995;268:1915–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.7604266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boland C R, Thibodeau S N, Hamilton S R, Sidransky D, Eshleman J R, Burt R W, Meltzer S J, Rodriguez-Bigas M A, Fodde R, Ranzani G N, Srivastava S. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ionov Y, Peinado M A, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M. Nature (London) 1993;363:558–561. doi: 10.1038/363558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bocker M, Schlegel J, Kullman F, Stumm G, Zirngibl H, Epplen J T, Ruschoff J. J Pathol. 1996;179:15–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199605)179:1<15::AID-PATH553>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duesberg P, Rasnick D, Li R, Winters L, Rausch C, Hehlmann R. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:4887–4906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cahill D P, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:M57–M60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]