Abstract

Tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein (TonEBP/nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 [NFAT5]) is a Rel homology transcription factor classically known for its osmosensitive role in regulating cellular homeostasis during states of hypo- and hypertonic stress. A recently growing body of research indicates that TonEBP is not solely regulated by tonicity, but that it can be stimulated by various tonicity-independent mechanisms in both hypertonic and isotonic tissues. Physiological and pathophysiological stimuli such as cytokines, growth factors, receptor and integrin activation, contractile agonists, ions, and reactive oxygen species have been implicated in the positive regulation of TonEBP expression and activity in diverse cell types. These new data demonstrate that tonicity-independent stimulation of TonEBP is critical for tissue-specific functions like enhanced cell survival, migration, proliferation, vascular remodeling, carcinoma invasion, and angiogenesis. Continuing research will provide a better understanding as to how these and other alternative TonEBP stimuli regulate gene expression in both health and disease.

Keywords: nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5, gene expression, osmotic stress

tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein (TonEBP) is an essential transcription factor required for the regulation of cellular homeostasis in response to hypertonicity-induced osmotic stress. TonEBP was initially identified following the detection of a tonicity-responsive enhancer element (TonE) in the promoter of the sodium chloride/betaine cotransporter gene (BGT1) responsible for restoring osmolyte balance in renal medullary cells (52). The TonE sequence from the BGT1 promoter was cloned using the yeast 1-hybrid method, which led to the identification of the osmosensitive transcription factor TonEBP (53). Also known as the nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 (NFAT5), TonEBP is a member of the Rel family of transcription factors that shares a conserved DNA binding domain with NFATc1–4 and nuclear factor-κB transcription factors (40). Although these transcription factors all possess a similar DNA binding sequence (GGAAA), TonEBP differs from NFATc1–4 proteins in that it does not have a calcineurin binding domain and is instead highly sensitive to NaCl-induced hypertonicity. In environments of high extracellular tonicity, the COOH-terminal transactivation domain of the TonEBP protein becomes phosphorylated, which results in the activation and nuclear translocation of the protein (13, 40, 53).

Because of an evolutionarily conserved mechanism, all mammalian cells are equipped to respond to hypertonic exposure by immediately allowing water to efflux from the cell and then gradually enhancing the accumulation of intracellular organic osmolytes such as betaine, taurine, sorbitol, and inositol (24, 75). TonEBP is the transcriptional regulator directly responsible for this accumulation of organic osmolytes to restore cellular homeostasis, and it does so by transcriptionally regulating genes such as the sodium/myoinositol cotransporter (SMIT) (53), sodium chloride/taurine cotransporter (TauT) (79), and aldose reductase (AR) (33). TonEBP also stimulates transcription of other genes to promote cell survival and mitogenesis under hypertonic stress (35). Thus TonEBP is a master regulator of cellular adaptation to hypertonic stress. Of note, TonEBP is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body (40, 69) and has been identified as being sensitive to hypertonicity in all cell types in which it has been studied, regardless of whether or not those tissue are physiologically hypertonic in vivo (16, 43, 71, 79).

It is without question that hypertonic stress plays a definitive role in the normal biological functions of the kidney, as daily NaCl osmolality levels can easily reach 1,000–1,200 mosmol/kg in the kidney medulla during antidiuresis (38, 74). Other slightly hypertonic tissues have been identified, such as the thymus, spleen, and liver (roughly 330–335 mosmol/kg compared with blood osmolality at 300 mosmol/kg) (18). Cells can also experience elevated periods of osmolality during tissue disregulation or injury as found in neurons during hypernatremia (up to 335 mosmol/kg) (2, 41) and cardiac myoblasts following myocardial infarction (up to 360 mosmol/kg) (70). Similarly, in very extreme cases, pathologies such as hypernatremia and diabetes mellitus can elevate serum tonicity levels up to 340 or 350 mosmol/kg, respectively (56). However, it is unknown whether these slightly elevated tissue osmolalities of up to 350 mosmol/kg have any true physiological effect in stimulating TonEBP protein in vivo. In vitro experiments indicate that tonicity levels of at least 380 mosmol/kg are required to detect a significant increase in TonEBP luciferase reporter activity in both Jurkat T-cells and splenocytes (18, 54). Osmolality levels must reach 370 mosmol/kg to stimulate proliferation in lymphocytes (18), whereas bone marrow-derived macrophages and mouse embryonic fibroblasts require hypertonicity levels of 430 and 480 mosmol/kg to activate TonEBP reporter activity (54). Therefore, although select tissues display slightly increased basal osmolalities, hypertonicity may not serve as the primary TonEBP-stimulating factor in these tissues. However, environmental tonicity may play a role in enhancing the effects of other TonEBP-stimulating factors. Thus an outstanding question and focus of this review is “What function does TonEBP serve in isotonic tissues?”

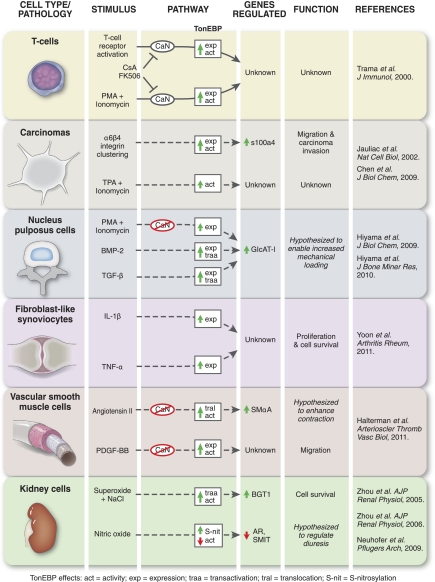

Recent research indicates that TonEBP has important functions in many isotonic tissues such as cancerous tumors, skeletal myoblasts, synovial fibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells (19, 30, 59, 77). Various tonicity-independent stimuli have been documented as regulating TonEBP in these and other isotonic tissues, as well as in some hypertonic tissues. It is the aim of this review to highlight the growing body of work identifying these alternative, tonicity-independent mechanisms of TonEBP induction and activation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Physiological and pathophysiological stimuli regulate tonicity-responsive enhanced binding protein (TonEBP) in diverse cell types. Novel, tonicity-independent stimuli regulate TonEBP expression, transactivation, nuclear translocation, reporter activity, and downstream TonEBP-dependent gene activation. Solid lines represent more defined signaling cascades, whereas dashed lines represent less defined pathways. In T-cells, T-cell receptor activation and PMA + ionomycin (a calcium ionophore) upregulate TonEBP expression and activity via the calcineurin (CaN) pathway. CaN inhibitors cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506 block T-cell receptor and PMA + ionomycin stimulation of TonEBP. In carcinomas, α6β4 integrin clustering stimulates TonEBP expression and activity leading to enhanced s100 calcium binding protein a4 (s100a4) gene expression and increased carcinoma migration and invasion. TPA + ionomycin stimulation also upregulates TonEBP activity in carcinomas. In nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc, PMA + ionomycin stimulates TonEBP expression, independent of calcineurin, which leads to increased β1,3-glucuroosyltransferase-I (GlcAT-I) gene expression. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and transforming growth factor β (TFG-β) both upregulate TonEBP expression and transactivation in nucleus pulposus cells resulting in increased GlcAT-1 expression. In fibroblast-like synoviocytes within rheumatoid arthritic joints, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) upregulate TonEBP expression resulting in fibroblast-like synoviocyte proliferation and increased cell survival. In vascular smooth muscle cells, angiotensin II stimulates TonEBP nuclear translocation and activity independent of calcineurin, which results in increased smooth muscle α-actin (SMαA) gene expression. Also in vascular smooth muscle cells, platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB) upregulates TonEBP expression and activity, independent of calcineurin, leading to increased smooth muscle cell migration. In kidney cells, superoxide + NaCl-induced hypertonicity augments TonEBP transactivation and activity resulting in increased expression of the sodium chloride/betaine cotransporter (BGT1) gene and increased kidney cell survival. Also in kidney cells, nitric oxide increases TonEBP S-nitrosylation leading to decreased TonEBP activity, inhibited expression of aldose reductase (AR), and sodium/myoinositol cotransporter (SMIT) gene expression and is believed to contribute to diuresis.

Role of TonEBP in Embryological and Fetal Development

TonEBP is required for mouse embryonic development and survival. TonEBP-null mice die prenatally or late in gestation (18, 39), and studies report that TonEBP-null mouse embryos have pronounced kidney medulla atrophy, are immunodeficient and hypernatremic, and suffer from improper heart development and impaired cardiac function (7, 39, 44). Increased TonEBP expression and localization of the protein in wild-type mice during embryonic development suggests that TonEBP plays a role during embryogenesis and fetal maturation (45). TonEBP expression is high in the brain and lens at embryonic day 10.5, upregulated in the liver by day 12.5, and is ubiquitously expressed throughout in the embryo by day 17.5 (45). It could be hypothesized that the process of rapid cellular division that occurs during embryogenesis and fetal development would generate an osmotic imbalance and subsequently activate TonEBP protein, but the osmolality levels surrounding the embryo in vivo remain undetermined. However, in vitro experiments have been performed in an effort to determine the optimal growth medium osmolality for embryonic development. One study determined that during the early stages of porcine embryonic development, embryos cultured in increased NaCl solutions (300–320 mosmol/kg) showed a more rapid rate of growth and decreased apoptosis compared with embryos in control media (260–270 mosmol/kg) (28). However, another similar study found the opposite to be true, that when rabbit embryos were cultured in a more isotonic media (270 mosmol/kg), there was increased blastocyst growth and development compared with embryos cultured in hypertonic (310 to 330 mosmol/kg) media (55). Additionally, a study conducted in humans showed that as human fetal age increases, amniotic fluid osmolality decreases, and amniotic fluid osmolalities of 250 mosmol/kg mark fetal maturity (51). Although these studies describe how alterations in systemic tonicity affect embryogenesis, they do not address the local osmotic imbalances that could possibly develop within the embryo due to differing cellular permeability in various stages of development. While systemic and local hyperosmolality may very well play a role in certain stages of embryonic development, the potential remains for other tonicity-independent mechanisms to regulate TonEBP expression during embryogenesis and fetal maturation.

Two papers provide such evidence for the tonicity-independent regulation of TonEBP-driven gene expression in embryonic cells (17, 22). Wild-type (WT) and TonEBP-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were taken from day 13.5 embryos, cultured in isotonic media, and stimulated with the calcium ionophore ionomycin and PMA. After ionomycin stimulation, WT MEFs exhibited increased promoter activity levels of two TonEBP-dependent genes aquaporin2 (AQP2)and β1,3-glucuroosyltransferase-I (GlcAT-I), whereas TonEBP-null MEFs displayed blunted AQP2 and GlcAT-I promoter activity (17, 22). Similarly, experiments modeling smooth muscle cell (SMC) differentiation from a multipotent cell line provide evidence for TonEBP regulation of cellular differentiation in an isotonic environment (19). A404 multipotent embryonal cells were cultured in isotonic media and treated with retinoic acid over a period of 7 days to direct the cells toward a SMC lineage (9). As SMC differentiation progressed over 7 days, TonEBP mRNA expression increased (19). Additionally, small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of TonEBP in the A404 cell line led to the attenuated expression of a TonEBP-dependent gene required for proper SMC function, smooth muscle α-actin (SMαA) (19). The first two studies demonstrate that calcium regulates TonEBP target gene expression in embryonic fibroblasts, whereas the last study shows that TonEBP expression and downstream gene transcription can take place in isotonic conditions during cellular differentiation. These findings suggest a critical role for the tonicity-independent stimulation of TonEBP in embryological development.

Tonicity-Independent Activation of TonEBP in T-Cells

The thymus is avital organ for the development and maturation of T-cells, and it provides a tightly controlled environment for immature thymocytes to develop into mature T-cells and be released into the peripheral tissues (58). Vapor pressure osmometry measurements have recorded basal thymus tissue osmolality as reaching levels of 330 mosmol/kg, which is significantly higher relative to serum osmolality measured at 305 mosmol/kg (18). It has been hypothesized that a localized environment of extracellular hypertonicity in the thymus could be caused by the high concentration of lymphocytes undergoing apoptosis during T-cell selection (68). A similar hyperosmotic environment can be found in the spleen, a site for T-cell storage, with values reaching 335 mosmol/kg (18). Although these slightly hypertonic tissues display significantly enhanced osmolality compared with serum, additional studies show that these tonicity levels may not be sufficient to engender an osmotic stress response resulting in TonEBP activation. For example, TonEBP is required for T-cell survival and proliferation during periods of high osmotic stress, but osmolality levels in these experiments reached 360–500 mosmol/kg before significant T-cell impairment could be measured (14, 18, 54). These levels are well above the calculated osmolality of the thymus and spleen (330 and 335 mosmol/kg, respectively) (18). Studies utilizing haplo insufficient TonEBP mice report that TonEBP+/− lymphocytes proliferate normally at 330–335 mosmol/kg, and it is only when osmolalities are >360 mosmol/kg that proliferation is impaired (18). Similarly, T-cells taken from a TonEBP-null mouse and transferred into a WT thymus were found to proliferate normally, even despite the slightly higher osmolality of the thymus (7). These data imply that the thymus and spleen do not provide a large enough hypertonic insult to impair lymphocyte function, which suggests that alternate mechanisms exist to stimulate TonEBP in T-cells.

The discovery that TonEBP expression was elevated in the thymus but relatively undetectable in unstimulated mature T-cells led to the identification of a tonicity-independent mechanism for TonEBP activation in T-cells (69). Trama et al. report that cross-linking of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and resulting T-cell mitogenesis induces TonEBP protein expression in primary T lymphocytes and Jurkat human T-cells (69). This TCR-mediated induction of TonEBP expression is distinct from the hyperosmotic activation of TonEBP in T-cells in that it involves the calcium/calcineurin signaling cascade and is blocked by the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506 (69). Of note, TCR stimulation of TonEBP does not affect gene transcription of hyperosmotically stimulated genes such as AR and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (15, 68, 69). This suggests that receptor-dependent induction of TonEBP serves a separate function from tonicity-dependent stimulation of TonEBP in T-cells. Trama et al. (69) additionally show that treatment of T-cells with the calcium ionophore ionomycin + PMA leads to enhanced TonEBP expression and transcription factor activity mediated through the calcineurin pathway. These results provide the first evidence of calcium-mediated regulation of TonEBP. While it is still undetermined, both TCR and calcium stimulation of TonEBP may play a role in T-cell development or proliferation in varying environmental conditions. Future research will be necessary to uncover the functional role of TCR and calcium-mediated activation of TonEBP and determine the subset of TonEBP-dependent genes regulated by these unique mechanisms of activation (Fig. 1).

TonEBP Expression in Carcinomas

TonEBP has been implicated as a central node for the stimulation of melanoma metastasis (3, 36). Knockdown of TonEBP decreases melanoma invasion, and the tumor suppressor miR-221 has been identified as negative regulator of TonEBP expression in cancer (36). Several studies conducted in human breast and colon carcinomas provide evidence for the tonicity-independent stimulation of TonEBP expression through α6β4 integrin clustering (12, 30). Integrins participate in mediating cellular migration through binding to extracellular matrix ligands and propagating signals to initiate cellular locomotion (29). Integrins also play a critical role in mechanotransduction by sensing various mechanical stresses and transferring those forces into chemical signals to elicit a cellular response (31). Clustering of α6β4 integrins is specifically associated with the promotion of carcinoma migration, invasion into surrounding tissues, and metastasis through the lymph and blood (50). Jauliac et al. (30) show a significant increase in α6β4 integrin clustering when cancer cells are treated with chemoattractant-rich NIH 3T3-conditioned medium, and α6β4 integrin clustering leads to the direct upregulation of TonEBP protein and transcription factor activity (30). Notably, α6β4-mediated upregulation of TonEBP results in enhanced carcinoma migration (30). TonEBP has also been shown to positively regulate expression of the pro-migratory gene, s100 calcium binding protein a4 (s100a4) in cancer cells that express the α6β4 integrin (12). Additionally, although it was not the main focus these studies, Jauliac et al. (30) show that TPA + ionomycin stimulation of breast carcinoma cells enhances TonEBP activity. As the authors did not pursue these experiments further, it remains to be determined whether ionomycin stimulation of TonEBP is calcineurin dependent and a regulator of carcinoma migration and invasion.

Since there is no documentation of carcinoma tissue osmolality, it is unknown if cancerous tumors possess an osmolality vastly different from that of the surrounding tissues or blood. Some hypothesize that in colon cancer, TonEBP can become activated by osmotic stress due to the elevated tonicity in the small intestine following a meal (measured to be around 430 mosmol/kg) (11, 26). However, this increase in osmolality is rapid, and levels return to isosmotic conditions within roughly 2 to 4.2 h (26, 34). This is largely due to hepatic osmoreceptors in the portal vein that sense acute increases in blood osmolality and signal the neural release of vasopressin (1, 6). Disconcordant with the evidence that the intestine rapidly returns to isosmotic conditions, experiments have been performed whereby colon cancer cells treated with 100 mM NaCl required 24 h to show an induction in TonEBP protein (11). It is unlikely that tumors in the colon would be subjected to hypertonic stress for such lengthy periods of time. Therefore, a more viable hypothesis is that α6β4 integrin clustering or other unidentified signaling mechanisms are activating TonEBP expression to further propagate carcinoma motility and metastasis (Fig. 1).

Diverse Simulation of TonEBP in Intervertebral Disc

The cartilaginous intervertebral discs of the spinal cord serve to cushion the vertebraas the spine rotates, flexes, and extends (27). Located at the center of the intervertebral disc is the gel-like nucleus pulposus (NP) that secretes collagen and proteoglycans (67). Unlike many of the isotonic tissues described in this review that do not experience large fluctuations in tonicity, the microenvironment of the intervertebral disc is consistently hypertonic, with osmolalities readily oscillating between 400 and 550 mosmol/kg (67). Although undetermined, fluctuations in tonicity resulting in intervertebral disc cell volume changes could place physical forces on the cells and lead to the mechanical stress activation of TonEBP. The hyperosmotic environment of the intervertebral disc allows for rapid water and osmolyte movement in and out of NP cells, which enables the spine to properly adapt to varying biomechanical forces throughout the day (67). NP cells secrete a molecule called aggrecan, which contains charged glycosoaminoglycan (GAG) side chains that are directly involved in raising or lowering tissue osmolality (46, 47). Additional osmolality control is mediated through (GlcAT-I), an enzyme that regulates GAG synthesis (32).

Multiple studies have highlighted the importance of hypertonicity-mediated regulation of TonEBP in NP cells (71, 72); however, new research indicates that tonicity is not the only factor regulating TonEBP in the in the osmodynamic environment of the intervertebral disc. Cells of the intervertebral disc can experience transient bursts of calcium during periods of increased tissue hyperosmolality, and it is hypothesized that these transient bursts promote actin stabilization for the adaptation of the intervertebral discs to differing biomechanical stresses (61). Hiyama et al. (22) show that treating NP cells with the calcium ionophore ionomycin + PMA results in a calcium-dependent increase in TonEBP mRNA and protein. Treatment of NP cells with the calcineurin inhibitors CsA and FK506 indicate that ionomycin-mediated activation of TonEBP expression is calcineurin independent (22). Additionally, ionomycin stimulates expression of GlcAT-I, an enzyme required for GAG synthesis involved in regulating intervertebral disc osmolality (22). TonEBP overexpression increases GlcAT-I promoter activity, and chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis shows TonEBP enrichment of the GlcAT-I promoter (22). In addition, both overexpression of adominant negative TonEBP and direct mutation of the TonE binding site on the GlcAT-I promoter inhibit an ionomycin-driven increase in GlcAT-I promoter activity (22). These data provide evidence for anionomycin-activated, calcineurin-independent stimulation of TonEBP and GlcAT-1 expression in NP cells.

Various growth factors provide additional signaling mechanisms for the regulation of GAG synthesis and water balance in NP cells (37, 64). Two such growth factors, bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and transforming growth factor-β (TFG-β), have recently been discovered as two additional positive regulators of TonEBP protein expression and transactivation in NP cells (23). Just as ionomycin stimulated a TonEBP-dependent upregulation of GlcAT-I promoter activity, BMP-2 and TFG-β induce GlcAT-I expression and promoter activity, and mutation of the TonE site in the GlcAT-I promoter results in suppressed GlcAT-I activity (23).

Regulation of TonEBP in the NP cells of the intervertebral discs is more complex than once thought, and hypertonic stress is no longer the only known mediator of in TonEBP activation and osmotic water balance (17, 71). Ionomycin-mediated calcium release serves to increase TonEBP expression and target gene regulation (22), as do the growth factors BMP-2 and TFG-β (23). The existence of various TonEBP-modulating pathways in NP cells highlights the importance of TonEBP-mediated GlcAT-I regulation of the osmotic environment for proper osmotic balance and healthy disc function under varying biomechanical forces (Fig. 1) (22, 23).

Role of TonEBP in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the synovial joints. Immune cells and fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) perpetuate this autoimmune disease by increasing FLS cellularity, protease production, and inflammation of the joint lining (10). FLS promote joint inflammation through the production inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6, and TNF-α (4). These cytokines can then act in a positive feedback loop to further enhance inflammation, vascular angiogenesis, and FLS proliferation (4).

It is hypothesized that cellular proliferation can create local hypertonic environments due to the depletion of intracellular organic osmolytes that occurs when larger macromolecules are formed within a cell (18, 25, 68). In regards to patients with RA, it seems plausible that the cell-dense, highly mitogenic and largely inflamed synovial tissues would exhibit increased hyperosmolality. However, recorded measurements of RA synovial fluid osmolality indicate that the joint synovium is mildly hypotonic to isotonic with osmolalities ranging from 268 to 280 mosmol/kg (5, 66, 77). In contrast, normal joint osmolality can range from <300 to 404 mosmol/kg depending on joint activity and exercise (5, 66). With the discovery that TonEBP was highly expressed in the FLS of patients with RA (48), and the knowledge that RA synovial joints are relatively isotonic, it was speculated that a tonicity-independent stimulus was responsible for TonEBP regulation in RA synovial tissues (77).

A recent discovery by Yoon et al. (77) has identified the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α as two potent inducers of TonEBP protein expression and nuclear translocation in FLS from RA synovial joints. Of note, IL-1β and TNF-α increased TonEBP expression in FLS from RA tissues but not from osteoarthritis synovial joints (77). Osteoarthritis is a noninflammatory degenerative joint disease; therefore, these data indicate that cytokine-mediated stimulation of TonEBP in FLS varies depending on the diseased joint environment. This additionally suggests that RA FLS are somewhat primed to respond to IL-1β and TNF-α signaling leading to the induction and trafficking of TonEBP protein.

Initial reports identifying TonEBP expression in RA FLS found a discernible correlation between TonEBP expression levels and FLS proliferation (48). Further studies demonstrated that siRNA-mediated knockdown of TonEBP in RA FLS inhibits both TNF-α and TNF-β-stimulated FLS proliferation (77). Of significance, in vivo studies using a mouse model of arthritis show that mice haploinsufficient in TonEBP have reduced arthritis compared with WT controls (77). TonEBP+/− mice exhibit decreased paw swelling, immune cell localization, FLS proliferation, and joint degeneration (77). TonEBP is also critical for FLS cell survival, and siRNA knockdown of TonEBP results in increased FLS cell death (77). Studies performed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) demonstrate that siRNA-mediated knockdown of TonEBP inhibits VEGF-induced HUVEC migration and chemotaxis (77). These findings indicate that TonEBP plays a role in vessel angiogenesis, a process that is central to RA initiation and propagation. Altogether, IL-1β and TNF-α signaling in the isotonic synovial tissues of RA patients play an important role in stimulating TonEBP expression and function, and the tonicity-independent activation of TonEBP serves to enhance angiogenesis, inflammation, and joint deterioration in RA (Fig. 1).

TonEBP Regulation of Vascular SMC Phenotype

SMCs in the arteries of the vasculature play an important role in vessel elasticity, contractility, and the overall maintenance of vascular tone (8). Various contractile agonists such as angiotensin II and endothelin 1 are released both systemically and from the local vasculature to promote SMC contraction and vasoconstriction (60). TonEBP expression in SMCs was previously unidentified until a recent report published from our lab demonstrated that TonEBP activation and downstream gene regulation is highly regulated by multiple tonicity-independent mechanisms in vascular SMCs. Of note, angiotensin II increases TonEBP nuclear translocation and TonEBP reporter activity in SMCs but does not alter TonEBP mRNA or protein expression (19). We additionally identified TonEBP as a positive regulator of the SMC-selective contractile gene SMαA (19). TonEBP binds to the intronic region of the SMαA gene and is required for the angiotensin II-mediated upregulation of SMαA promoter activity and expression (19). We also have unpublished evidence indicating that TonEBP+/− mice have significantly decreased blood pressure at 5 wk of age compared with WT mice, which suggests that TonEBP plays an important role in SMC contraction and vessel function.

Since SMCs are not terminally differentiated, they are capable of undergoing phenotypic modulation from a healthy, contractile state to a migratory, proliferative, or inflammatory phenotype during periods of chronic vascular disease, i.e., atherosclerotic plaque development, or acute vascular injury, i.e., stent deployment to restore arterial blood flow (20, 42, 60). We report that TonEBP not only regulates the contractile SMC phenotype but that it also plays a role in vascular injury and is required for SMC migration (19). TonEBP protein is highly expressed in the SMCs of human and murine arteries with overlying atherosclerotic lesions and is upregulated in rat carotid arteries following 21 days of acute vascular balloon injury (19). During acute and chronic vascular injury, platelets and other cells of the vasculature release platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB) to stimulate SMC migration and proliferation (65). PDGF-BB was found to significantly increase both TonEBP protein expression and TonEBP reporter activity (19). Additionally, siRNA-mediated knockdown of TonEBP inhibited both PDGF-BB and serum-induced SMC migration, which indicates that TonEBP plays an important role in SMC function (19).

Apart from exceptional cases such as severe dehydration, hypernatremic disorders, and life-threatening diabetes mellitus complications, blood osmolality is tightly regulated around 280–300 mosmol/kg. Because of this, it was hypothesized that hypertonicity was not the primary regulator of TonEBP expression and function in SMCs (19). It is therefore of great significance that angiotensin II and PDGF-BB have been identified as two physiologically relevant stimuli that drive TonEBP expression and/or activity in SMCs. Although the possibility exists that hypertonic microenvironments may be present within the vascular wall that could affect how other factors stimulate TonEBP, this hypothesis is difficult to test and remains a speculation. Similarly, it is hypothesized that mechanical stress may serve to activate TonEBP protein in SMCs, but these studies have not been completed. In summary, TonEBP plays a unique, bidirectional role in regulating SMC phenotypic modulation (Fig. 1). Further studies will be necessary to uncover the downstream signaling pathways mediating TonEBP activation in SMCs, and additional in vivo studies will help to better determine TonEBP function and gene regulation in both the healthy artery and in vascular disease.

Complex Regulation of TonEBP in the Kidney

Renal medullary cells are capable of surviving in a highly hypertonic environment largely in part due to the NaCl-driven activation of TonEBP leading to enhanced water and osmolyte movement across the cellular membrane (21, 73). Another product of NaCl-induced osmotic stress is the stimulation of oxidative stress and mitogenesis (62, 80), and high levels of NaCl have been shown to enhance reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the kidney (76, 78). Two studies published by Zhou et al. (81, 82) demonstrate that NaCl induces mitochondrial ROS expression and that superoxide, specifically, positively regulates TonEBP reporter activity and transactivation, while hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide do not. Treatment of HEK293 cells with a superoxide inhibitor led to the suppression of both NaCl-stimulated TonEBP reporter activity and NaCl-induced expression of the TonEBP-dependent gene BGT1 (82). NaCl-driven increases in ROS production promotes TonEBP transactivating activity but does not affect TonEBP nuclear translocation, which indicates that ROS serve to activate TonEBP and NaCl then stimulates its nuclear translocation (81). Of note, the authors were not able to stimulate TonEBP transcriptional activity by ROS alone in isotonic conditions nor did addition of exogenous ROS add to the NaCl-mediated stimulation of TonEBP (82). Therefore, ROS-driven activation of TonEBP is in fact tonicity dependent in the kidney, as NaCl-induced hypertonicity is required for ROS production and downstream ROS-mediated effects in renal medullary cells. However, without ROS production during hypertonic stress, TonEBP activity and target gene expression is significantly attenuated (81, 82).

As osmolality in the kidney rapidly fluctuates, TonEBP-dependent gene expression enables renal medullary cells to restore osmotic balance; however, other mechanisms also exist to assist the kidney in its regulation of fluid and osmolyte homeostasis. Nitric oxide (NO) is abundantly generated and released by the kidney to promote sodium and water excretion, thereby decreasing extracellular hypertonicity and the need for TonEBP-mediated effects (49, 63). While all of the other tonicity-independent TonEBP stimuli described in this review positively regulate TonEBP expression, activity, and/or downstream gene regulation, NO is unique in that it negatively regulates TonEBP-dependent gene expression in both hypertonic and isotonic conditions (57). Introduction of NO donors into MDCK cell culture media enhances S-nitrosylation of TonEBP protein and decreases TonEBP binding to the target genes AR and SMIT (57). Given that TonEBP promotes cell survival, it seems plausible to infer that NO inhibition of TonEBP would enhance cell death; however, no increased cell death was observed (57). Since NO signaling in the renal medulla enhances sodium and water excretion and therefore decreases extracellular hypertonicity, it is believed that NO inhibits TonEBP transcriptional activity because transcription of osmoprotective genes would no longer be required (Fig. 1) (57). The combined actions of TonEBP gene regulation and NO signaling provide a critical means of checks and balances for the control of kidney homeostasis, which allows for the tight regulation of solute and water balance critical for proper kidney function.

Conclusion

Although TonEBP protein is expressed at basal levels ubiquitously throughout the body, only a limited number of tissues are slightly hypertonic or become hyperosmotic during extreme stress (40, 53, 69). Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that tonicity-independent mechanisms exist to regulate TonEBP in isotonic tissues. Many novel TonEBP-stimulating factors have been identified, such as TCR and ionomycin in T-cells, α6β4 integrin clustering, and ionomycin in carcinomas, ionomycin, BMP-2, and TGF-β in nucleus pulposus cells, 1L-1β, and TNF-α in fibroblast-like synoviocytes, angiotensin II and PDGF-BB in vascular SMCs, and superoxide and NO in kidney cells (Fig. 1). These stimuli serve to modulate TonEBP protein expression, transactivation, and/or nuclear localization, leading to TonEBP target gene transcription in isotonic (and some hypertonic) environments. The tonicity-independent regulation of TonEBP in various organs and cells of the body is critical for the maintenance of cellular functionality, namely, cell survival, mitogenesis and migration. Further research will uncover how these and other alternative TonEBP stimuli drive gene expression and regulate cellular function in both health and disease.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.A.H., H.M.K., and B.R.W. conception and design of research; J.A.H. analyzed data; J.A.H. interpreted results of experiments; J.A.H. prepared figures; J.A.H. drafted manuscript; J.A.H., H.M.K., and B.R.W. edited and revised manuscript; J.A.H., H.M.K., and B.R.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grant funding for the authors was provided by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-81682 and RO1-DK-61677 by and the American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate Predoctoral Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adachi A, Niijima A, Jacobs HL. An hepatic osmoreceptor mechanism in the rat: electrophysiological and behavioral studies. Am J Physiol 231: 1043–1049, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Hypernatremia. N Engl J Med 342: 1493–1499, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asirvatham AJ, Gregorie CJ, Hu Z, Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. Micro-RNA targets in immune genes and the Dicer/Argonaute and ARE machinery components. Mol Immunol 45: 1995–2006, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev 233: 233–255, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baumgarten M, Bloebaum RD, Ross SD, Campbell P, Sarmiento A. Normal human synovial fluid: osmolality and exercise-induced changes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 67: 1336–1339, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baylis PH. Osmoregulation and control of vasopressin secretion in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 253: R671–R678, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berga-Bolanos R, Drews-Elger K, Aramburu J, Lopez-Rodriguez C. NFAT5 regulates T lymphocyte homeostasis and CD24-dependent T cell expansion under pathologic hypernatremia. J Immunol 185: 6624–6635, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bevan JA, Bevan RD. Developmental influences on vascular structure and function. Ciba Found Symp 83: 94–107, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blank RS, Swartz EA, Thompson MM, Olson EN, Owens GK. A retinoic acid-induced clonal cell line derived from multipotential P19 embryonal carcinoma cells expresses smooth muscle characteristics. Circ Res 76: 742–749, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bresnihan B. Pathogenesis of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 26: 717–719, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen M, Sastry SK, O'Connor KL. Src kinase pathway is involved in NFAT5-mediated S100A4 induction by hyperosmotic stress in colon cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C1155–C1163, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen M, Sinha M, Luxon BA, Bresnick AR, O'Connor KL. Integrin alpha6beta4 controls the expression of genes associated with cell motility, invasion, and metastasis, including S100A4/metastasin. J Biol Chem 284: 1484–1494, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Hypertonicity-induced phosphorylation and nuclear localization of the transcription factor TonEBP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C248–C253, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drews-Elger K, Ortells MC, Rao A, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Aramburu J. The transcription factor NFAT5 is required for cyclin expression and cell cycle progression in cells exposed to hypertonic stress. PLos One 4: e5245, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esensten JH, Tsytsykova AV, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Ligeiro FA, Rao A, Goldfeld AE. NFAT5 binds to the TNF promoter distinctly from NFATp, c, 3 and 4, and activates TNF transcription during hypertonic stress alone. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 3845–3854, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Franchi-Gazzola R, Visigalli R, Dall'Asta V, Sala R, Woo SK, Kwon HM, Gazzola GC, Bussolati O. Amino acid depletion activates TonEBP and sodium-coupled inositol transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C1465–C1474, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gajghate S, Hiyama A, Shah M, Sakai D, Anderson DG, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. Osmolarity and intracellular calcium regulate aquaporin2 expression through TonEBP in nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc. J Bone Miner Res 24: 992–1001, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Go WY, Liu X, Roti MA, Liu F, Ho SN. NFAT5/TonEBP mutant mice define osmotic stress as a critical feature of the lymphoid microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10673–10678, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halterman JA, Kwon HM, Zargham R, Schoppee Bortz PD, Wamhoff BR. Nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2287–2296, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamon M, Bauters C, McFadden EP, Wernert N, Lablanche JM, Dupuis B, Bertrand ME. Restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Eur Heart J 16 Suppl I: 33–48, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Handler JS, Kwon HM. Transcriptional regulation by changes in tonicity. Kidney Int 60: 408–411, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hiyama A, Gajghate S, Sakai D, Mochida J, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. Activation of TonEBP by calcium controls β1,3-glucuronosyltransferase-I expression, a key regulator of glycosaminoglycan synthesis in cells of the intervertebral disc. J Biol Chem 284: 9824–9834, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hiyama A, Gogate SS, Gajghate S, Mochida J, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. BMP-2 and TGF-beta stimulate expression of beta1,3-glucuronosyl transferase 1 (GlcAT-1) in nucleus pulposus cells through AP1, TonEBP, and Sp1: role of MAPKs. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1179–1190, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ho SN. Intracellular water homeostasis and the mammalian cellular osmotic stress response. J Cell Physiol 206: 9–15, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ho SN. The role of NFAT5/TonEBP in establishing an optimal intracellular environment. Arch Biochem Biophys 413: 151–157, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Houpt TR. Patterns of duodenal osmolality in young pigs fed solid food. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 261: R569–R575, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Humzah MD, Soames RW. Human intervertebral disc: structure and function. Anat Rec 220: 337–356, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hwang IS, Park MR, Moon HJ, Shim JH, Kim DH, Yang BC, Ko YG, Yang BS, Cheong HT, Im GS. Osmolarity at early culture stage affects development and expression of apoptosis related genes (Bax-alpha and Bcl-xl) in pre-implantation porcine NT embryos. Mol Reprod Dev 75: 464–471, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110: 673–687, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jauliac S, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Shaw LM, Brown LF, Rao A, Toker A. The role of NFAT transcription factors in integrin-mediated carcinoma invasion. Nat Cell Biol 4: 540–544, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katsumi A, Orr AW, Tzima E, Schwartz MA. Integrins in mechanotransduction. J Biol Chem 279: 12001–12004, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kitagawa H, Ujikawa M, Sugahara K. Developmental changes in serum UDP-GlcA:chondroitin glucuronyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 271: 6583–6585, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ko BC, Ruepp B, Bohren KM, Gabbay KH, Chung SS. Identification and characterization of multiple osmotic response sequences in the human aldose reductase gene. J Biol Chem 272: 16431–16437, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ladas SD, Isaacs PE, Sladen GE. Post-prandial changes of osmolality and electrolyte concentration in the upper jejunum of normal man. Digestion 26: 218–223, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee SD, Choi SY, Lim SW, Lamitina ST, Ho SN, Go WY, Kwon HM. TonEBP stimulates multiple cellular pathways for adaptation to hypertonic stress: organic osmolyte-dependent and -independent pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F707–F715, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levy C, Khaled M, Iliopoulos D, Janas MM, Schubert S, Pinner S, Chen PH, Li S, Fletcher AL, Yokoyama S, Scott KL, Garraway LA, Song JS, Granter SR, Turley SJ, Fisher DE, Novina CD. Intronic miR-211 assumes the tumor suppressive function of its host gene in melanoma. Mol Cell 40: 841–849, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li J, Yoon ST, Hutton WC. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) on matrix production, other BMPs, and BMP receptors in rat intervertebral disc cells. J Spinal Disord Tech 17: 423–428, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Linshaw MA. Selected aspects of cell volume control in renal cortical and medullary tissue. Pediatr Nephrol 5: 653–665, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lopez-Rodriguez C, Antos CL, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Lin F, Novobrantseva TI, Bronson RT, Igarashi P, Rao A, Olson EN. Loss of NFAT5 results in renal atrophy and lack of tonicity-responsive gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 2392–2397, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lopez-Rodriguez C, Aramburu J, Rakeman AS, Rao A. NFAT5, a constitutively nuclear NFAT protein that does not cooperate with Fos and Jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7214–7219, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loyher ML, Mutin M, Woo SK, Kwon HM, Tappaz ML. Transcription factor tonicity-responsive enhancer-binding protein (TonEBP) which transactivates osmoprotective genes is expressed and upregulated following acute systemic hypertonicity in neurons in brain. Neuroscience 124: 89–104, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature 407: 233–241, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maallem S, Berod A, Mutin M, Kwon HM, Tappaz ML. Large discrepancies in cellular distribution of the tonicity-induced expression of osmoprotective genes and their regulatory transcription factor TonEBP in rat brain. Neuroscience 142: 355–368, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mak MC, Lam KM, Chan PK, Lau YB, Tang WH, Yeung PK, Ko BC, Chung SM, Chung SK. Embryonic lethality in mice lacking the nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 protein due to impaired cardiac development and function. PLos One 6: e19186, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maouyo D, Kim JY, Lee SD, Wu Y, Woo SK, Kwon HM. Mouse TonEBP-NFAT5: expression in early development and alternative splicing. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F802–F809, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maroudas A. Distribution and diffusion of solutes in articular cartilage. Biophys J 10: 365–379, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maroudas A, Muir H, Wingham J. The correlation of fixed negative charge with glycosaminoglycan content of human articular cartilage. Biochim Biophys Acta 177: 492–500, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Masuda K, Masuda R, Neidhart M, Simmen BR, Michel BA, Muller-Ladner U, Gay RE, Gay S. Molecular profile of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis depends on the stage of proliferation. Arthritis Res 4: R8, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mattson DL, Wu F. Control of arterial blood pressure and renal sodium excretion by nitric oxide synthase in the renal medulla. Acta Physiol Scand 168: 149–154, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mercurio AM, Rabinovitz I. Towards a mechanistic understanding of tumor invasion–lessons from the alpha6beta 4 integrin. Semin Cancer Biol 11: 129–141, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miles PA, Pearson JW. Amniotic fluid osmolality in assessing fetal maturity. Obstet Gynecol 34: 701–706, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miyakawa H, Woo SK, Chen CP, Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Cis- and trans-acting factors regulating transcription of the BGT1 gene in response to hypertonicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F753–F761, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miyakawa H, Woo SK, Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein, a rel-like protein that stimulates transcription in response to hypertonicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2538–2542, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Morancho B, Minguillon J, Molkentin JD, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Aramburu J. Analysis of the transcriptional activity of endogenous NFAT5 in primary cells using transgenic NFAT-luciferase reporter mice. BMC Mol Biol 9: 13, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Naglee DL, Maurer RR, Foote RH. Effect of osmolarity on in vitro development of rabbit embryos in a chemically defined medium. Exp Cell Res 58: 331–333, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Neuhofer W. Role of NFAT5 in inflammatory disorders associated with osmotic stress. Curr Genomics 11: 584–590, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Neuhofer W, Fraek ML, Beck FX. Nitric oxide decreases expression of osmoprotective genes via direct inhibition of TonEBP transcriptional activity. Pflügers Arch 457: 831–843, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nishino M, Ashiku SK, Kocher ON, Thurer RL, Boiselle PM, Hatabu H. The thymus: a comprehensive review. Radiographics 26: 335–348, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. O'Connor RS, Mills ST, Jones KA, Ho SN, Pavlath GK. A combinatorial role for NFAT5 in both myoblast migration and differentiation during skeletal muscle myogenesis. J Cell Sci 120: 149–159, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev 84: 767–801, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pritchard S, Erickson GR, Guilak F. Hyperosmotically induced volume change and calcium signaling in intervertebral disk cells: the role of the actin cytoskeleton. Biophys J 83: 2502–2510, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Qin S, Ding J, Takano T, Yamamura H. Involvement of receptor aggregation and reactive oxygen species in osmotic stress-induced Syk activation in B cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 262: 231–236, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Raij L, Baylis C. Glomerular actions of nitric oxide. Kidney Int 48: 20–32, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Risbud MV, Di Martino A, Guttapalli A, Seghatoleslami R, Denaro V, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ, Shapiro IM. Toward an optimum system for intervertebral disc organ culture: TGF-beta 3 enhances nucleus pulposus and anulus fibrosus survival and function through modulation of TGF-beta-R expression and ERK signaling. Spine 31: 884–890, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ross R, Glomset J, Kariya B, Harker L. A platelet-dependent serum factor that stimulates the proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71: 1207–1210, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shanfield S, Campbell P, Baumgarten M, Bloebaum R, Sarmiento A. Synovial fluid osmolality in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 289–295, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sivan S, Neidlinger-Wilke C, Wurtz K, Maroudas A, Urban JP. Diurnal fluid expression and activity of intervertebral disc cells. Biorheology 43: 283–291, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Trama J, Go WY, Ho SN. The osmoprotective function of the NFAT5 transcription factor in T cell development and activation. J Immunol 169: 5477–5488, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Trama J, Lu Q, Hawley RG, Ho SN. The NFAT-related protein NFATL1 (TonEBP/NFAT5) is induced upon T cell activation in a calcineurin-dependent manner. J Immunol 165: 4884–4894, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tranum-Jensen J, Janse MJ, Fiolet WT, Krieger WJ, D'Alnoncourt CN, Durrer D. Tissue osmolality, cell swelling, and reperfusion in acute regional myocardial ischemia in the isolated porcine heart. Circ Res 49: 364–381, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tsai TT, Danielson KG, Guttapalli A, Oguz E, Albert TJ, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. TonEBP/OREBP is a regulator of nucleus pulposus cell function and survival in the intervertebral disc. J Biol Chem 281: 25416–25424, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tsai TT, Guttapalli A, Agrawal A, Albert TJ, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. MEK/ERK signaling controls osmoregulation of nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc by transactivation of TonEBP/OREBP. J Bone Miner Res 22: 965–974, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tyagi MG, Nandhakumar J. Newer insights into renal regulation of water homeostasis. Indian J Exp Biol 46: 89–93, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Woo SK, Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Bidirectional regulation of tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein in response to changes in tonicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F1006–F1012, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yancey PH, Clark ME, Hand SC, Bowlus RD, Somero GN. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science 217: 1214–1222, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yang T, Zhang A, Honeggar M, Kohan DE, Mizel D, Sanders K, Hoidal JR, Briggs JP, Schnermann JB. Hypertonic induction of COX-2 in collecting duct cells by reactive oxygen species of mitochondrial origin. J Biol Chem 280: 34966–34973, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yoon HJ, You S, Yoo SA, Kim NH, Kwon HM, Yoon CH, Cho CS, Hwang D, Kim WU. NFAT5 is a critical regulator of inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63: 1843–1852, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang Z, Dmitrieva NI, Park JH, Levine RL, Burg MB. High urea and NaCl carbonylate proteins in renal cells in culture and in vivo, and high urea causes 8-oxoguanine lesions in their DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 9491–9496, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang Z, Ferraris JD, Brooks HL, Brisc I, Burg MB. Expression of osmotic stress-related genes in tissues of normal and hyposmotic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F688–F693, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhang Z, Yang XY, Cohen DM. Urea-associated oxidative stress and Gadd153/CHOP induction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F786–F793, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zhou X, Ferraris JD, Burg MB. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species contribute to high NaCl-induced activation of the transcription factor TonEBP/OREBP. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1169–F1176, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhou X, Ferraris JD, Cai Q, Agarwal A, Burg MB. Increased reactive oxygen species contribute to high NaCl-induced activation of the osmoregulatory transcription factor TonEBP/OREBP. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F377–F385, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]