Abstract

Illegal drug use remains a serious threat to community health in Canada, yet there has been a remarkable discordance between scientific evidence and policy in this area, with most resources going to drug use prevention and drug law enforcement activities that have proven ineffective. Conversely, evidence-based drug treatment programs have been chronically underfunded, despite their cost-effectiveness. Similarly, various harm reduction strategies, such as needle exchange, supervised injecting programs and opioid substitution therapy, have also proven effective at reducing drug-related harm but receive limited government support. Accordingly, Canadian society would greatly benefit from reorienting its drug policies on addiction, with consideration of addiction as a health issue, rather than primarily a criminal justice issue. In this context, and in light of the simple reality that drug prohibition has not effectively reduced the availability of most illegal drugs and has instead contributed to a vast criminal enterprise and related violence, among other harms, alternatives should be prioritized for evaluation.

The use of illegal drugs remains a serious threat to community health.1 However, despite the substantial social costs attributable to illegal drugs, a well-described discordance between scientific evidence and policy exists in this area,2 such that most resources go to drug law enforcement activities that have not been well evaluated.3,4 When the Office of the Auditor General of Canada last reviewed the country’s drug strategy, in 2001, it estimated that of the $454 million spent annually on efforts to control illicit drugs, $426 million (93.8%) was devoted to law enforcement.5 The report further concluded, “Of particular concern is the almost complete absence of basic management information on spending of resources, on expectations, and on results of an activity that accounts for almost $500 million each year.”5

Despite the long-standing emphasis on drug law enforcement, the federal government has recently further prioritized this approach by developing legislation requiring mandatory minimum prison sentences for minor drug law offences.6 This article reviews the impact of conventional drug policies employed internationally and describes evidence-based steps to reduce the health and social costs attributable to drug policies in Canada.

Impact of drug law enforcement

Law enforcement has a critical role to play in community safety. However, as was observed with the emergence of a violent illegal market under alcohol prohibition in the United States in the 1920s, the vast illegal market that has emerged under drug prohibition has proven remarkably resistant to law enforcement efforts, while unintended consequences have similarly emerged.4,7

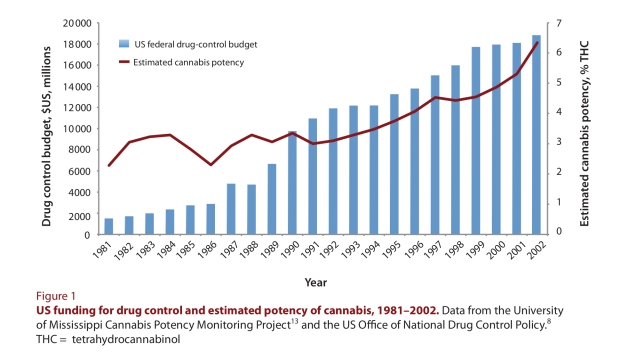

Given its well-funded drug surveillance systems, the United States has generated excellent data for assessing the impact of drug law enforcement. Remarkably, despite an estimated US$1 trillion spent since former US president Richard Nixon first declared his country’s “war on drugs,” the effort to reduce drug supply and drive up drug prices through aggressive drug law enforcement appears to have been ineffective.8-10 Instead, in recent decades, the prices of the more commonly used illegal drugs (e.g., cannabis and cocaine) have actually gone down, while potency has risen dramatically.11,12 To highlight the limited ability of drug law enforcement to constrain cannabis supply, Figure 1 shows that the estimated potency of US cannabis (in terms of its active ingredient, tetrahydrocannabinol) has increased by more than 170%, from approximately 2.3% in 1981 to 6.3% in 2002, despite an increase in US federal anti-drug expenditures from US$1.5 billion in 1981 to more than US$18 billion in 2002.8,13

Figure 1.

US funding for drug control and estimated potency of cannabis, 1981–2002

Opponents of drug policy reform commonly argue that drug use would increase if health-based models were emphasized over drug law enforcement,14 but we are unaware of any research to support this position. In fact, a recent World Health Organization study demonstrated that international rates of drug use were unrelated to how vigorously drug laws were enforced, concluding that “countries with stringent user-level illegal drug policies did not have lower levels of use than countries with liberal ones.”15 In addition, although reducing the availability of cannabis has been a central focus of drug law enforcement efforts, over the past 30 years of cannabis prohibition the drug has remained “almost universally available to American 12th graders,” according to US drug use surveillance systems funded by the US National Institutes of Health, with 80%–90% of survey respondents saying that the drug is “very easy” or “fairly easy” to obtain.16

Besides the fact that drug law enforcement is costly and ineffective, over-reliance on this approach has also resulted in a range of unintended consequences, which were recently summarized in the official conference declaration of the XVIII International AIDS Conference in Vienna, Austria (Box 1).17 The International AIDS conference has become the largest biennial public health conference in the world. The so-called Vienna Declaration has now been endorsed by thousands of individuals, including leaders in science and medicine, Nobel laureates and former heads of state. In Canada, the declaration has already been endorsed by the Canadian Public Health Association, and by the Urban Public Health Network, which represents the medical officers of health of Canada's 18 largest cities.

Box 1.

Harms of traditional drug policies, as listed in the Vienna Declaration

Models to reduce harm: those that do not work and those that do

Of critical importance to any discussion of efforts to reduce harm is the fact that some commonly employed school-based drug prevention programs have repeatedly been proven ineffective in randomized trials,18 yet they continue to receive substantial federal funding in both the United States and Canada. Other programs, including the Canadian federal government’s antidrug media campaign, are often implemented without evidence to support their efficacy and despite evidence that they may be harmful.19 For instance, controlled trials of antidrug media messages have suggested that they may result in harmful assumptions among youth about drug use.20 Moreover, a US$42.7 million federal government–funded evaluation of the ongoing National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign in the United States recently concluded that its US$1.4 billion advertising campaign had been ineffective at curtailing rates of drug use by youth and may actually have had the negative effect of inflating youths’ perceptions regarding rates of drug use among their peers.21

Conversely, a substantial research base points toward more effective models that have been proven to reduce health-related and community concerns attributable to drug use, as well as reducing the unintended effects of drug policies.7,17,22-24 This substantial body of evidence leads to several observations, as outlined below.

Evidence-based drug treatment programs are cost effective, and significant benefits should be derived, at both individual and societal levels, through an increase in scale.25 Consistent with the recent recommendations of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security,26 this would include expanding access to existing evidence-based models of care such as medical and non-medical withdrawal programs, programs to manage concurrent mental health problems and addictions, ambulatory and residential treatment programs, and opioid substitution therapies.17 Similarly, given the substantial health (e.g., infectious disease, overdose death) and social (e.g., crime) concerns caused by heroin addiction in urban areas27 and the potential for heroin by prescription to reduce these harms among those in whom conventional treatments fail, the prescription of heroin could be considered for selected patients with opioid addiction that is refractory to all other treatment modalities.23,28,29

Various harm reduction strategies, such as needle exchange programs and methadone maintenance therapy, have also proven effective in reducing drug-related harm and have not been associated with unintended consequences.22 The joint recommendations recently released by several United Nations agencies, including the World Health Organization, provide a strong scientific basis for expanding harm reduction efforts.22 Beyond these recommendations, the recent consensus statement from Canada’s National Specialty Society for Community Medicine,30 which endorses the scale-up of supervised consumption facilities, reflects the compelling national and international evidence to support the controlled expansion of these programs in urban areas with high concentrations of public drug use and related harms. Since 1986, more than 90 supervised drug consumption facilities have been set up in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Luxembourg, Norway, Canada and Australia, mainly in cities with large populations of street injection drug users.29,31,32

The criminalization of people who use drugs continues to prove ineffective in reducing rates of drug use and has instead contributed to substantial health-related harms (Box 1).7 Portugal, which decriminalized all drug use in 2001, has seen no increases in drug-related harms. Instead, a published review of the effects of decriminalization noted that this change was followed by “reductions in problematic use, drug-related harms and criminal justice overcrowding,” with rates of drug use remaining among the lowest in the European Union.24

Accordingly, Canadian society would greatly benefit from a reorienting of its drug policies on addiction—that is, with consideration of addiction as a health issue, rather than primarily a criminal justice issue. In this context, evidence-based community diversion programs for non-violent drug offenders could be expanded and evaluated to replace more costly and less effective incarceration efforts.33,34 In the states of New York, Michigan, Massachusetts and Connecticut, for instance, mandatory minimum legislation for non-violent drug offences is being repealed, with several other US jurisdictions set to follow suit.

Finally, in light of the simple reality that drug prohibition has not effectively reduced the availability of most illegal drugs and has instead contributed to a vast criminal enterprise and related violence,4 among other harms, alternatives should be prioritized for urgent evaluation.12 In addition, controlled regulation of illegal drugs may offer several advantages over the unregulated market currently controlled by organized crime groups, and there is substantial evidence from research on illicit drugs, tobacco and alcohol regarding how regulatory tools can more safely control drug availability while having the potential to positively influence cultural norms related to drug use (Table 1).35-37 For instance, comparisons of cannabis use between the United States and Holland, where cannabis is sold to adults for recreational use through government-sanctioned “coffee shops,” have revealed that rates of use are higher in the United States, and researchers have concluded that “Drug policies may have less impact on cannabis use than is currently thought.”38 Similarly, evaluations of cannabis use by US youth have demonstrated that rates of use have not increased in states where medical marijuana has been legalized.39

Table 1.

Models and mechanisms for reducing cannabis-related harms in a regulated market

In this context, several Canadian bodies, including the Canadian Public Health Association40 and the Health Officers Council of British Columbia,41 have recently endorsed the evaluation of a regulated market for all currently illegal drugs. Although a full description of regulatory models is outside the scope of this paper, it is important to stress that regulatory tools would need to be closely evaluated and should be tailored to each specific substance. Examples of regulatory tools that have been described for cannabis are presented in Table 1.36

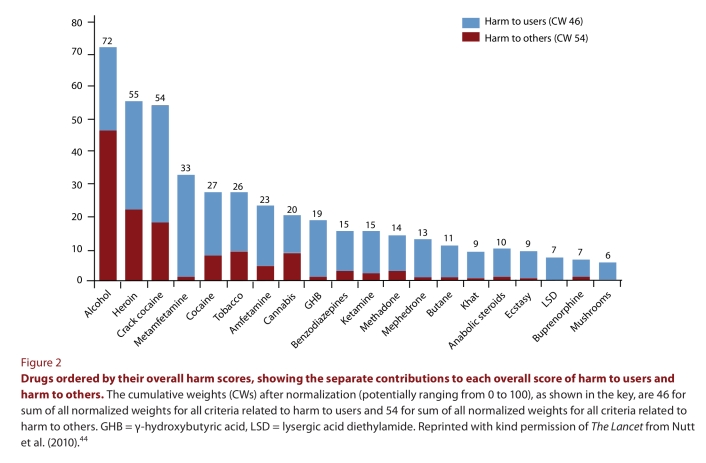

Advocating for drug policy reform has traditionally been politically unpopular, but a recent Angus Reid poll estimated that 50% of Canadians already support legalization of cannabis.42 In this context, it is noteworthy that, although cannabis is not free from harms, recent reviews have suggested that it is less harmful than many currently legal drugs, including alcohol and tobacco, as well as several commonly used pharmaceutical drugs.43 A recent study based on a 16-level matrix of harm, spanning individual physical and social harms, demonstrated the relative safety of cannabis over alcohol (Figure 2).44 In light of the persistently widespread availability and relative safety of cannabis in comparison to existing legal drugs, as well as the crime and violence that exist secondary to prohibition of this drug,4 there is a need for discussion about the optimal regulatory strategy to reduce the harms of cannabis use while also reducing unintended policy-attributable consequences (e.g., the organized crime that has emerged under prohibition).8,38

Figure 2.

Drugs ordered by their overall harm scores, showing the separate contributions to each overall score of harm to users and harm to others

A call for action

In 2005, as part of the renewal of Canada’s National Drug Strategy, an exhaustive national consultative process led by Health Canada and the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse culminated in a “national framework for action” to reduce the harms associated with drugs in Canada.45 This inclusive process, which involved all stakeholder groups, aimed to remove the rhetoric and emotion that have traditionally guided Canada’s response to illicit drugs and instead sought to incorporate the best available scientific evidence into the country’s drug policy. The central aim of the strategy was “to ensure that Canadians can live in a society increasingly free of the harms associated with problematic substance use,” and it differed from the US approach in emphasizing harm reduction.45

In 2007, however, the federal government abandoned this framework in favour of a new anti-drug strategy, which removed support for the evidence-based harm reduction programs recommended by the World Health Organization. The new strategy has also supported various drug-use prevention measures that have proven ineffective and potentially harmful elsewhere.18,20,21 Lastly, as described above, more recent plans to enact costly mandatory minimum sentences for drug law violations highlight a complete departure from evidence-based policy-making.33

Publications in medical journals often attract transient media attention, but their impact can be short-lived without meaningful debate on the part of policy-makers. We urge that such an informed debate take place without delay to increase the relevance of scientific evidence in drug policy decision-making.

Disclaimer

The ideas expressed in this article are the authors’ opinions as public health physicians and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of their employers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deborah Graham, Carmen Rock, Peter Vann and Dan Werb for research and administrative assistance and Dr. André Corriveau for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We also thank the MAC AIDS Fund for research support.

Biographies

Evan Wood, MD, PhD, ABIM, FRCPC, is Co-Director of the Urban Health Research Initiative at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. He is also a Professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of AIDS, at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Moira McKinnon, MD, MBBS, FAFPHM, is the Chief Medical Health Officer for Saskatchewan.

Robert Strang, MD, FRCPC, is the Chief Medical Health Officer for Nova Scotia.

Perry R. Kendall, OBC, MBBS, MSc, FRCPC, is the Chief Medical Health Officer for British Columbia and a Clinical Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: None.

Contributors: All authors made a substantial contribution to the study conception, critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Fischer Benedikt, Rehm Jürgen, Patra Jayadeep, Kalousek Kate, Haydon Emma, Tyndall Mark, El-Guebaly Nady. Crack across Canada: Comparing crack users and crack non-users in a Canadian multi-city cohort of illicit opioid users. Addiction. 2006;101(12):1760–1770. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01614.x. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reuter Peter. Why does research have so little impact on American drug policy? Addiction. 2001;96(3):373–376. doi: 10.1080/0965214002005437. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9633731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wodak Alex, McLeod Leah. The role of harm reduction in controlling HIV among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S81–S92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327439.20914.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werb Dan, Rowell Greg, Guyatt Gordon, Kerr Thomas, Montaner Julio, Wood Evan. Effect of drug law enforcement on drug market violence: A systematic review. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(2):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.02.002. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0955395911000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of the Auditor General of Canada. 2001 Report of the Auditor General of Canada. 2001. Chapter 11—Illicit drugs: the federal government's role. http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_200112_11_e_11832.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick M. Omnibus crime bill hearings underway in Senate. CBC News. 2011. Feb 7, http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/story/2012/02/01/pol-senate-committee-crime-bill.html.

- 7.Beyrer Chris, Malinowska-Sempruch Kasia, Kamarulzaman Adeeba, Kazatchkine Michel, Sidibe Michel, Strathdee Steffanie A. Time to act: a call for comprehensive responses to HIV in people who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):551–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60928-2. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673610609282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Centre for Science in Drug Policy. Tools for debate: US federal government data on cannabis prohibition. 2010. [accessed 2010 Dec]. http://www.icsdp.org/docs/ICSDP-2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood Evan, Tyndall Mark W, Spittal Patricia M, Li Kathy, Anis Aslam H, Hogg Robert S, Montaner Julio S G, O'Shaughnessy Michael V, Schechter Martin T. Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: investigation of a massive heroin seizure. CMAJ. 2003 Jan 21;168(2):165–169. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/12538544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babor T, Caulkins J, Edwards G, Fischer B, Foxcroft D, Humphreys K, Obot I S, Rehm J, Reuter P, Room R, Rossow I, Strang J. Drug policy and the public good. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reuter Peter. Ten years after the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS): assessing drug problems, policies and reform proposals. Addiction. 2009;104(4):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02536.x. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2010. 2010. [accessed 2011 May 2]. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2010.html.

- 13.National Center for Natural Products Research (NCNPR), Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Quarterly Report, Potency Monitoring Project, Report 107, September 16, 2009 thru December 15, 2009. University (MS): NCNPR, Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi; 2010. http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/sourcefiles/UMPMC-quarterly-monitoring-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood Evan, Montaner Julio S, Kerr Thomas. Illicit drug addiction, infectious disease spread, and the need for an evidence-based response. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(3):142–143. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70021-5. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309908700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degenhardt Louisa, Chiu Wai-Tat, Sampson Nancy, Kessler Ronald C, Anthony James C, Angermeyer Matthias, Bruffaerts Ronny, de Giovanni Girolamo, Gureje Oye, Huang Yueqin, Karam Aimee, Kostyuchenko Stanislav, Lepine Jean P, Mora Maria E M, Neumark Yehuda, Ormel J H, Pinto-Meza Alejandra, Posada-Villa José, Stein Dan J, Takeshima Tadashi, Wells J E. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008 Jul 1;5(7):141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/18597549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston L D, O’Malley P M, Bachman J G, Schulenberg J E. Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975-2005. Volume I. Secondary school students (NIH pub. no. 06-5883) Bethesda (MD): National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Vienna Declaration. [accessed 2010 Dec]. http://www.viennadeclaration.com.

- 18.West Steven L, O'Neal Keri K. Project D.A.R.E. Outcome Effectiveness Revisited. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1027–1029. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.6.1027. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/15249310/?tool=pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werb D, Mills E, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Montaner J, Wood E. The effectiveness of anti-illicit drug public-service announcements: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(10):834–840. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.125195. http://jech.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/jech.2010.125195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishbein Martin, Hall-Jamieson Kathleen, Zimmer Eric, von Ina, Haeften, Nabi Robin. Avoiding the boomerang: testing the relative effectiveness of antidrug public service announcements before a national campaign. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):238–245. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.238. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/11818299/?tool=pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Government Accountability Office. Contractor’s national evaluation did not find that the youth anti-drug media campaign was effective in reducing youth drug use. 2006. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d06818.pdf.

- 22.WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS technical Guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users. 2009. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/OMSTargetSettingGuide.pdf.

- 23.Oviedo-Joekes Eugenia, Brissette Suzanne, Marsh David C, Lauzon Pierre, Guh Daphne, Anis Aslam, Schechter Martin T. Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 20;361(8):777–786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes C E, Stevens A. What can we learn from the Portuguese decriminalization of illicit drugs. Br J Criminol. 2010;50(6):999–1022. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azq038. http://bjc.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1093/bjc/azq038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsden John, Eastwood Brian, Bradbury Colin, Dale-Perera Annette, Farrell Michael, Hammond Paul, Knight Jonathan, Randhawa Kulvir, Wright Craig. Effectiveness of community treatments for heroin and crack cocaine addiction in England: a prospective, in-treatment cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374(9697):1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61420-3. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673609614203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security. Mental health and drug and alcohol addiction in the federal correctional system. 2010. [accessed 2011]. http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=4864852&Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=40&Ses=3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wall Ronald, Rehm Jurgen, Fischer Benedikt, Brand's Bruna, Gliksman Louis, Stewart Jennifer, Medved Wendy, Blake Joan. Social costs of untreated opioid dependence. J Urban Health. 2000;77(4):688–722. doi: 10.1007/BF02344032. http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/BF02344032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strang John, Metrebian Nicola, Lintzeris Nicholas, Potts Laura, Carnwath Tom, Mayet Soraya, Williams Hugh, Zador Deborah, Evers Richard, Groshkova Teodora, Charles Vikki, Martin Anthea, Forzisi Luciana. Supervised injectable heroin or injectable methadone versus optimised oral methadone as treatment for chronic heroin addicts in England after persistent failure in orthodox treatment (RIOTT): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9729):1885–1895. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60349-2. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673610603492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm Jürgen, Gschwend Patrick, Steffen Thomas, Gutzwiller Felix, Dobler-Mikola Anja, Uchtenhagen Ambros. Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of injectable heroin prescription for refractory opioid addicts: a follow-up study. Lancet. 2001 Oct 27;358(9291):1417–1423. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06529-1. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673601065291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Specialty Society for Community Medicine. Supervised drug consumption sites and InSite program [position statement] Ottawa: The Society; 2009. [accessed 2012 Feb 7]. http://nsscm.ca/Resources/Documents/ECAC%20Docs/NSSCMs_Position_on_Supervised_Consumption_Sites.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerr Thomas, Kimber Jo, DeBeck Kora, Wood Evan. The role of safer injection facilities in the response to HIV/AIDS among injection drug users. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):158–164. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0023-8. http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/s11904-007-0023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall Brandon D L, Milloy M J, Wood Evan, Montaner Julio S G, Kerr Thomas. Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America's first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62353-7. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673610623537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimber J, Dolan K, van Beek I, Hedrich D, Zurhold H. Drug consumption facilities: an update since 2000. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22(2):227–233. doi: 10.1080/095952301000116951. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1080/095952301000116951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. Mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses: why everyone loses. 2006. [accessed 2010]. http://www.aidslaw.ca/publications/interfaces/downloadFile.php?ref=1455.

- 35.Rethinking America's "War on Drugs" as a public-health issue. Lancet. 2001 Mar 31;357(9261):971. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673600042422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Room R. A cannabis reader: global issues and local experiences. Monograph series 8, vol. 1. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2008. In thinking about cannabis policy, what can be learned from alcohol and tobacco? [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolles S. After the war on drugs: blueprint for regulation. Bristol (UK): Transform Drug Policy Foundation; 2009. http://www.tdpf.org.uk/blueprint%20download.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordt Carlos, Stohler Rudolf. Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment case register analysis. Lancet. 2006;367(9525):1830–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68804-1. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673606688041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinarman Craig, Cohen Peter D A, Kaal Hendrien L. The limited relevance of drug policy: cannabis in Amsterdam and in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):836–842. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.5.836. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.94.5.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Keefe K, Earleywine M, Mirken B. Marijuana use by young people: The impact of state marijuana laws. 2007. http://www.mainecommonsense.org/pdf/TeenUseReport_0407.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canadian Public Health Association. Canadian Public Health Association 2007 Resolutions. [2010]. http://www.cpha.ca/uploads/resolutions/2007_e.pdf.

- 42.Health Officers Council of British Columbia. A public health approach to drug control in Canada. Discussion paper. 2005. http://www.cfdp.ca/bchoc.pdf.

- 43.Angus Reid Public Opinion. Half of Canadians support the legalization of marijuana. 2010. [accessed 2010]. http://www.angus-reid.com/polls/43593/half-of-canadians-support-the-legalization-of-marijuana/

- 44.Nutt David J, King Leslie A, Phillips Lawrence D Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet. 2010;376(9752):1558–1565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=21036393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Health Canada Drug Strategy and Controlled Substances Programme and Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. National framework for action to reduce the harms associated with alcohol and other drugs and substances in Canada. First edition. 2005. [2010]. http://www.nationalframework-cadrenational.ca/images/uploads/file/ccsa0113232005_e.pdf.