Abstract

Objectives. Our goal in this study was to better understand racial and socioeconomic status (SES) variations in experiences of racial and nonracial discrimination.

Methods. We used 1999 and 2000 data from the YES Health Study, which involved a community sample of 50 Black and 50 White respondents drawn from 4 neighborhoods categorized according to racial group (majority Black or majority White) and SES (≤ 150% or > 250% of the poverty line). Qualitative and quantitative analyses examined experiences of discrimination across these neighborhoods.

Results. More than 90% of Blacks and Whites described the meaning of unfair treatment in terms of injustice and felt certain about the attribution of their experiences of discrimination. These experiences triggered similar emotional reactions (most frequently anger and frustration) and levels of stress across groups, and low-SES Blacks and Whites reported higher levels of discrimination than their moderate-SES counterparts.

Conclusions. Experiences of discrimination were commonplace and linked to similar emotional responses and levels of stress among both Blacks and Whites of low and moderate SES. Effects were the same whether experiences were attributed to race or to other reasons.

Racial discrimination persists in the United States,1–3 and perceptions of discrimination are associated with negative health outcomes,4–20 whether discrimination is attributed to race or not and whether its targets are members of racial or ethnic minority groups or Whites.5,17–19 Discrimination also helps to account for racial disparities in health.8–16

In this study, we focused on 4 core questions about potential race and socioeconomic differences relevant to assessments of discrimination. First, to what extent do White and Black, poor and nonpoor Americans understand race-based discrimination differently? Second, do these groups differ in their uncertainty about how to make sense of incidents of perceived unfairness, given that such attributional ambiguity can lead to health-damaging worry and rumination?5,20 Third, do these groups differ in frequency of discrimination experiences across life domains? Finally, do they differ in the extent to which they attribute unfair treatment to racial versus non–race-based discrimination? Some researchers frame questions about discrimination in terms of unfair treatment and then ascertain the reason for the experience with a follow-up question,8,21 but it is unclear whether questions framed in this manner truly capture racial discrimination.22

METHODS

We derived our data from the YES Health Study, a quantitative and qualitative cross-sectional exploratory investigation conducted in a midwestern metropolitan area from 1999 to 2000. The sample consisted of 100 adults 25 to 55 years of age, 25 from each of 4 neighborhoods categorized according to racial group (White, Black, or African American) and household income (low socioeconomic status [SES], defined as ≤ 150% of the poverty line, and middle SES, defined as > 250% of the poverty line). Details on the research methods are available elsewhere.23,24 The 50 Black respondents were sampled from 3 largely Black census block groups (1 of low SES and 2 of moderate SES). The 50 White respondents were sampled from 3 largely White census block groups (25 from moderate-SES groups and 25 each from 2 low-SES groups). Trained race-matched interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews.

Respondents were initially asked whether they had ever been treated unfairly or badly because of their race, ancestry, or national origin. They were then asked an open-ended question about what the word unfair meant to them. Next, a 19-item expanded version of the Major Experiences of Discrimination Scale8,21 was used to assess lifetime discrimination in 5 domains: employment (unfairly fired, not hired, passed over for a raise, denied a promotion), housing (unfairly prevented from moving into a neighborhood, neighbors make life difficult, made to move out), education (unfairly discouraged by a teacher, denied a scholarship), police and courts (unfairly stopped, searched, or questioned by police; physically threatened or abused by police; suspected or accused of doing something illegal), and service provision (unfairly denied a bank loan, denied medical care or provided worse care than others, receiving inferior service from a plumber or car mechanic). A residual open-ended “other” domain was also included.

Respondents indicated the frequency of occurrence for each event, and, for the most recent experience of each type, they reported their perception of the main reason for the experience (racial vs nonracial), how certain they were about this reason (certain [absolutely positive and pretty sure] vs having some doubt [somewhat doubtful and very doubtful]), and how they felt when it happened. They also rated the extent to which the most recent event was stressful on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all stressful) to 3 (very stressful).

Two coders analyzed responses to the open-ended question regarding the meaning of unfair treatment to uncover recurrent themes. All responses were categorized as to whether respondents’ definitions of unfair treatment reflected notions of inequality or injustice. We conducted bivariate analyses to explore levels of discrimination (racial and nonracial) across the 4 sampled neighborhoods. We then examined how attributional ambiguity, emotional responses, and stress ratings varied across the neighborhood groups. We used the Fisher exact test for categorical outcomes and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous outcomes.

RESULTS

Ninety-three percent of the respondents described the meaning of unfair treatment in terms of inequality and injustice (e.g., as “unkind” and “unjust”). This pattern was consistent across racial and SES groups. Almost half of White respondents (47%) perceived unfair racial treatment as reverse discrimination (being denied opportunities because non-Whites receive preferential treatment). Blacks focused on unequal opportunities and being viewed as less capable or deserving.

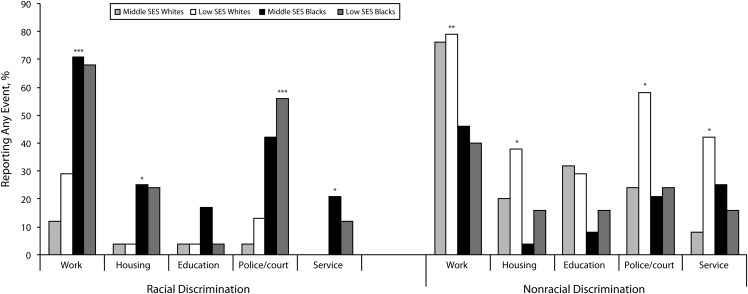

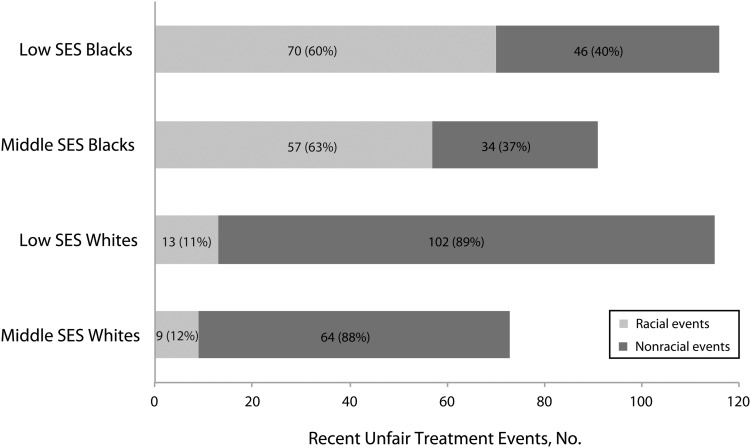

Mean lifetime numbers of unfair experiences did not differ according to race (4.4 among middle-SES Whites, 5.9 among low-SES Whites, 5.8 among middle-SES Blacks, and 6.5 among low-SES Blacks; P = .27). Black respondents viewed most of their unfair experiences as racial, whereas White respondents typically viewed them as nonracial (Figure 1). Experiences of discrimination were more prevalent among individuals of low SES than middle SES (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1—

Prevalence of perceived lifetime racial and nonracial discrimination, by race and socioeconomic status (SES): YES Health Study, 1999-2000.

Note. The percentages shown are the percentages of the sample reporting any of the types of racial and nonracial unfair treatment assessed within each broad domain. For each domain, Fisher exact tests were used to examine group differences in proportions of racial and nonracial events. *P <.05; **P <.01; ***P <.001.

FIGURE 2—

Levels of perceived racial and nonracial discrimination, by race and socioeconomic status (SES): YES Health Study, 1999-2000.

Note. Percentages in parentheses represent the distribution of the most recent racial and nonracial events reported by each group. Levels are shown by counts of racial and nonracial events for each race–SES group (aggregated from the 19 potential types of discrimination experiences reported).

We found little evidence of attributional ambiguity. Ninety-six percent of low-SES Black respondents were certain in their attributions of events as racially based, as were 97% of low-SES White respondents and all middle-SES Black and White respondents. Similarly, 94% of low-SES Black respondents were certain in their attributions of non–race-based experiences of discrimination, as were 95% of low-SES White respondents, 90% of middle-SES Black respondents, and 92% of middle-SES White respondents.

Anger and frustration were the most common emotional reactions to discrimination (Table 1). This pattern was generally consistent across racial and SES groups. Experiences of discrimination were uniformly perceived as stressful, with no statistically significant variation across groups for either racial or nonracial events.

TABLE 1—

Reported Emotional Responses to and Stressfulness Associated With Experiences of Racial and Nonracial Discrimination: YES Health Study, 1999–2000

| Racial Discrimination |

Nonracial Discrimination |

|||||||

| Middle-SES Whites | Low-SES Whites | Middle-SES Blacks | Low-SES Blacks | Middle-SES Whites | Low-SES Whites | Middle-SES Blacks | Low-SES Blacks | |

| Emotional response, % | ||||||||

| Angry | 33 | 77 | 70 | 71 | 69 | 63 | 65 | 76 |

| Frustrated | 78 | 46 | 54 | 63 | 61 | 63 | 53 | 48 |

| Sad | 22 | 15 | 21 | 13 | 22 | 12 | 6 | 7 |

| Powerless | 11 | 23 | 19 | 34 | 30 | 27 | 29 | 11 |

| Hopeless | 0 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 3 | 7 |

| Scared | 11 | 23 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 9 |

| Vulnerable | 22 | 0 | 14 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 4 |

| Humiliated | 22 | 8 | 23 | 19 | 28 | 25 | 3 | 15 |

| Vengeful | 11 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 19 | 8 | 3 | 7 |

| Inferior | 11 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 13 | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| Not surprised/resigned | 22 | 8 | 25 | 29 | 22 | 9 | 29 | 9 |

| Mean stressfulness score (range = 0–3)a | 1.94 | 2.30 | 1.87 | 1.73 | 2.16 | 1.91 | 1.86 | 1.94 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status. The percentages shown are based on denominators of total recent racial and nonracial unfair treatment events reported by each group. Column totals may exceed 100 because respondents could select multiple emotions.

Group differences in average stressfulness scores assessed via analysis of variance were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Both Black and White respondents understood unfair treatment as capturing injustice, suggesting traditional understandings of discrimination. We also found that ambiguity about the cause of discrimination was rare. Levels of ambiguity could be higher for chronic experiences such as those captured by the Everyday Discrimination Scale,8 a widely used instrument designed to capture discrimination.

Our finding that rates of reported discrimination were higher among low-SES Blacks and Whites than among their middle-class counterparts is inconsistent with previous research.5,6 This result may reflect the restricted SES range in our sample, the high stressor levels among disadvantaged Whites and Blacks, or our assessment of discrimination with a larger number of questions than typically used. We also found that Whites, particularly low-SES Whites, reported high levels of discrimination (mainly nonracial). Recent research indicates that when Whites live in economically deprived geographic contexts similar to those of African Americans, racial disparities in health are minimized.25–27 The contribution of discrimination to the poor health of Whites of very low SES should be explored.

Neither emotional reactions to discrimination nor ratings of stressfulness varied markedly by race, SES, or type of discrimination, suggesting that the generic experience of discrimination generates psychological distress regardless of the attribution and the characteristics of the target. This is consistent with equity theory,28 previous health research,29 and recent neuroimaging studies.30 The extent to which different reactions to discrimination may reflect perceptions of different types of moral violations31 and lead to different disease pathways32 is a priority for future research. Our findings need to be replicated in larger, representative samples to improve the measurement of discrimination and understand its role in health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant P01 MH58565). Preparation of the article was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant 3 U-01 HL 087322-02S1, a research supplement to grant U-01 HL 087322-02) and by the National Cancer Institute (grant P50 CA 148596).

We thank Liz Cavano and Maria Simoneau for assistance in preparing the article.

Human Participant Protection

The YES Health Study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Pager D. The mark of a criminal record. Am J Sociol. 2003;108(5):937–975 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pager D, Western B, Bonikowski B. Discrimination in a low-wage labor market: a field experiment. Am Sociol Rev. 2009;74(5):777–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(4):991–1013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):130–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren XS, Amick B, Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in health: the interplay between discrimination and socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(2):151–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustillo S, Krieger N, Gunderson EP, Sidney S, McCreath H, Kiefe CI. Self-reported experiences of racial discrimination and black-white differences in preterm and low-birthweight deliveries: the CARDIA Study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2125–2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pole N, Best S, Metsler T, Marmar C. Why are Hispanics at greater risk for PTSD. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2005;11(2):144–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson A, Gillies M, Howard PJ, Coffin J. It's enough to make you sick: the impact of racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(4):322–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams D, Gonzalez H, Williams S, Mohammed S, Moomal H, Stein D. Perceived discrimination, race, and health in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):441–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, Waldegrave K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in New Zealand: cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2006;367(9527):2005–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas KS, Nelesen RA, Malcarne VL, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE. Ethnicity, perceived discrimination, and vascular reactivity to phenylephrine. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(5):692–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adegbembo AO, Tomar SL, Logan HL. Perception of racism explains the difference between blacks’ and whites’ level of healthcare trust. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):792–798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis TT, Kravitz HM, Janssen I, Powell LH. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and visceral fat in middle-aged African-American and Caucasian women. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(11):1223–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunte HE. Association between perceived interpersonal everyday discrimination and waist circumference over a 9-year period in the midlife development in the United States Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(11):1232–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman EM, Williams DR, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Chronic discrimination predicts higher circulating levels of E-selectin in a national sample: the MIDUS study. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(5):684–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DR, Neighbors HW. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):800–816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):208–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown TN. Measuring self-perceived racial and ethnic discrimination in social surveys. Sociol Spectr. 2001;21(3):377–392 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rooks R, Xu Y, Holliman B, Williams D. Discrimination and mental health among black and white adults in the YES Health study. Race Soc Probl. 2011;3(3):182–196 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyserman D, Uskul AK, Yoder N, Nesse RM, Williams DR. Unfair treatment and self-regulatory focus. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(3):505–512 [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ, Mance GA, Jackson J. Overcoming confounding of race with socioeconomic status and segregation to explore race disparities in smoking. Addiction. 2007;102(suppl 2):65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorpe RJ, Jr, Brandon DT, LaVeist TA. Social context as an explanation for race disparities in hypertension: findings from the Exploring Health Disparities in Integrated Communities (EHDIC) Study. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(10):1604–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaVeist T, Thorpe R, Galarraga J, Bower K, Gary-Webb T. Environmental and socio-economic factors as contributors to racial disparities in diabetes prevalence.J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1144–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams JS, Berkowitz L. Inequity in social exchange. : Berkowitz L, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1965:267–299 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dion KL. The social psychology of perceived prejudice and discrimination. Can Psychol. 2002;43(1):1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabibnia G, Satpute AB, Lieberman MD. The sunny side of fairness: preference for fairness activates reward circuitry (and disregarding unfairness activates self-control circuitry). Psychol Sci. 2008;19(4):339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rozin P, Lowery L, Imada S, Haidt J. The CAD triad hypothesis: a mapping between three moral emotions (contempt, anger, disgust) and three moral codes (community, autonomy, divinity). J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(4):574–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendes WB, Major B, McCoy S, Blascovich J. How attributional ambiguity shapes physiological and emotional responses to social rejection and acceptance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94(2):278–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]