Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of golimumab over 104 weeks in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis.

Methods

At baseline, patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (n=356) were randomly assigned (1:1.8:1.8) to subcutaneous injections of placebo (group 1), golimumab 50 mg (group 2) or golimumab 100 mg (group 3) every 4 weeks. At week 16, patients in groups 1 and 2 with <20% improvement in total back pain and morning stiffness entered early escape to 50 or 100 mg, respectively. At week 24, patients still receiving placebo crossed over to golimumab 50 mg. Findings through week 24 were previously reported; those through week 104 are presented herein.

Results

At week 104, 38.5%, 60.1% and 71.4% of patients in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively, had at least 20% improvement in the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society response criteria (ASAS20); 38.5%, 55.8% and 54.3% had an ASAS40 response and 21.8%, 31.9% and 30.7% were in ASAS partial remission. Mean Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index scores were <3 at week 104 for all the treatment regimens. Golimumab safety through week 104 was similar to that through week 24.

Conclusion

Clinical response that was achieved by patients receiving golimumab through 24 weeks was sustained through 52 and 104 weeks. The golimumab safety profile appeared to be consistent with the known safety profile of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

Golimumab is a human monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α that is administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks. We previously reported the 24-week results of the double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled GO-RAISE (A Multicenter Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial of Golimumab, a Fully Human Anti-TNFα Monoclonal Antibody, Administered Subcutaneously, in Subjects with Active Ankylosing Spondylitis) study, in which we evaluated the efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS).1 The primary end point of the GO-RAISE study was achieved; 59% of patients in the 50-mg group and 60% of patients in the 100-mg group achieved at least 20% improvement in the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society response criteria (ASAS20) at week 14 compared with 22% in the placebo group (p<0.001 for comparisons of placebo with each golimumab group). No unexpected adverse events were observed through 24 weeks of golimumab treatment. Patients were followed up for up to 5 years, with the blind maintained through week 104 (for the type of treatment, placebo or golimumab, through week 24 and, following crossover, for the golimumab dose through week 104) to assess the long-term effects of golimumab therapy. Here we present the 104-week efficacy and safety findings from the GO-RAISE study.

Patients and methods

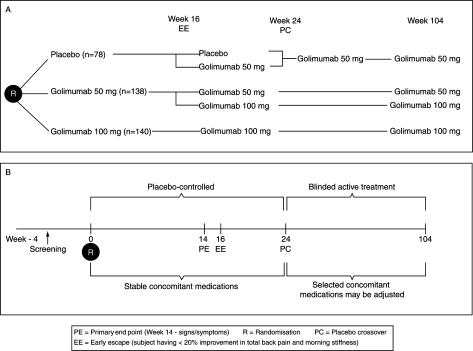

Details of the GO-RAISE study design, along with complete patient inclusion criteria, have been previously published.1 Briefly, patients had AS, as defined according to the 1984 New York Criteria,2 for at least 3 months before the first administration of study agent and an inadequate response to current or previous treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1.8:1.8 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of placebo (group 1), golimumab 50 mg (group 2) or golimumab 100 mg (group 3) every 4 weeks (figure 1). Concomitant use of methotrexate, sulphasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids and NSAIDs at stable doses was permitted as previously described.1

Figure 1.

Study schema showing randomisation (A) and major study time points (B).

At week 16, patients with less than 20% improvement from baseline in total back pain and morning stiffness entered early escape, such that their study medication was adjusted in a double-blind fashion. Patients in group 1 initiated treatment with golimumab 50 mg instead of placebo injections, and patients in group 2 had their golimumab dose increased from 50 to 100 mg; patients in group 3 did not have their study medication adjusted even if they met the early escape criteria.

At week 24, all remaining patients in group 1 who had been receiving placebo injections began receiving golimumab 50 mg; all other patients continued to receive their assigned treatment (from randomisation or early escape). Injections continued to be administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks through week 100, with final study assessments at week 104. While the placebo-controlled portion of the study ended at week 24, study participants and investigators remained blinded through week 104 as to the golimumab dose (50 or 100 mg). After week 52, patients were allowed to inject the study agent at home and were asked to return for study visits every 12 weeks. Serum samples were collected at weeks 24, 52 and 104 and assessed for the presence of antibodies to golimumab using a previously described assay.3

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each site. All patients gave written informed consent.

We evaluated the response to treatment by determining the proportions of patients with an ASAS20 or ASAS40 response, ASAS partial remission (defined as a value below 2 in each of the four ASAS domains) and at least 50% improvement in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index4 (BASDAI50 response). Changes from baseline in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI),5 Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) based on a linear method6 7 and physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS, respectively) scores of the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)8 were used to assess physical function, range of motion and health-related quality of life, respectively. The proportions of patients achieving an Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)9 <1.1 (indicating inactive disease) or <2.1 (indicating moderate disease activity) were also determined. This was performed as a post hoc analysis, as this measure was designed following the start of this trial.

No statistical comparisons were made for efficacy results after week 24 because all patients were receiving golimumab. Efficacy data are presented using two approaches:

Intention to treat: patients who met the treatment failure criteria at week 141 and those who entered early escape at week 16 were considered to be non-responders at week 104. In addition, patients who discontinued treatment because of an unsatisfactory therapeutic effect after week 24 or who were missing all ASAS components were considered to be non-responders at week 104. For patients who did not meet the treatment failure criteria, the missing ASAS components at week 104 were replaced with the last non-missing value. Patients were categorised according to their original randomly assigned treatment group. Thus, group 1 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to placebo and received golimumab 50 mg at week 16 if they met the criteria for early escape or crossed over to 50 mg at week 24. Group 2 comprised patients who were initially assigned to golimumab 50 mg and received that dose throughout the study or received 100 mg at week 16 if they met the criteria for early escape. Group 3 comprised patients who were initially assigned to golimumab 100 mg and received that dose throughout the study.

By treatment regimen: treatment regimen 1 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to placebo at baseline and who either entered early escape at week 16 to receive golimumab 50 mg through week 104 or crossed over at week 24 to receive golimumab 50 mg through week 104. Treatment regimen 2 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to golimumab 50 mg at baseline and who either entered early escape at week 16 to receive golimumab 100 mg through week 104 or continued 50 mg through week 104. Treatment regimen 3 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to golimumab 100 mg at baseline and who did not receive study medication adjustments. Concomitant medications were stable through week 24, but selected medications could be adjusted after week 24 (see Methods for details). Actual observed ASAS20 and ASAS40 response rates through week 104 are presented without data imputation. Patients who entered early escape were counted in the treatment regimen to which they were originally assigned. Efficacy data (ASAS20; ASAS40; BASDAI50 and changes in BASDAI, BASFI, BASMI and SF-36 scores) are also presented by actual treatment received based on the early escape status (see table 1 for categories).

Table 1.

Efficacy measures through week 104 by early escape status: observed data presented without imputation

| Placebo → golimumab 50 mg (group 1) | Golimumab 50 mg (group 2) | Golimumab 100 mg (group 3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early escape (week 16–104)* | Crossover (week 24–104)† | 50 mg only‡ | Early escape (week 16–104) 50 mg →100 mg* | 100 mg only‡ | 100 mg → 100 mg* | |

| Randomised patients (n) | 41 | 35 | 113 | 25 | 107 | 33 |

| ASAS20 | ||||||

| Week 28 | 23/40 (57.5) | 26/35 (74.3) | 85/102 (83.3) | 6/25 (24.0) | 78/100 (78.0) | 3/32 (9.4) |

| Week 52 | 25/34 (73.5) | 29/34 (85.3) | 85/98 (86.7) | 9/21 (42.9) | 86/99 (86.9) | 10/28 (35.7) |

| Week 104 | 24/31 (77.4) | 28/31 (90.3) | 77/90 (85.6) | 7/16 (43.8) | 77/93 (82.8) | 14/25 (56.0) |

| ASAS40 | ||||||

| Week 28 | 15/40 (37.5) | 21/35 (60.0) | 66/102 (64.7) | 3/25 (12.0) | 70/100 (70.0) | 2/32 (6.3) |

| Week 52 | 19/34 (55.9) | 27/34 (79.4) | 73/98 (74.5) | 2/21 (9.5) | 73/99 (73.7) | 8/28 (28.6) |

| Week 104 | 21/31 (67.7) | 28/31 (90.3) | 74/90 (82.2) | 5/16 (31.3) | 64/93 (68.8) | 7/25 (28.0) |

| BASDAI50 | ||||||

| Week 28 | 17/41 (41.5) | 21/35 (60.0) | 65/103 (63.1) | 3/25 (12.0) | 66/100 (66.0) | 1/32 (3.1) |

| Week 52 | 17/35 (48.6) | 27/34 (79.4) | 70/99 (70.7) | 1/21 (4.8) | 76/99 (76.8) | 6/29 (20.7) |

| Week 104 | 21/33 (63.6) | 27/32 (84.4) | 72/91 (79.1) | 5/16 (31.3) | 65/93 (69.9) | 6/25 (24.0) |

| Change in BASDAI§ | ||||||

| Week 28 | −2.4±2.49 | −3.3±2.47 | −3.8±2.15 | −0.8±1.88 | −3.9±2.41 | −0.5±1.55 |

| Week 52 | −3.4±2.60 | −4.4±2.02 | −4.0±2.09 | −1.3±1.58 | −4.4±2.24 | −1.3±1.96 |

| Week 104 | −3.6±2.25 | −4.6±2.42 | −4.2±2.19 | −2.0±2.33 | −4.4±2.25 | −1.8±1.93 |

| Change in BASFI§ | ||||||

| Week 28 | −1.5±2.86 | −1.5±2.30 | −2.4±2.12 | −0.3±1.52 | −2.5±2.26 | 0.6±2.48 |

| Week 52 | −3.0±3.07 | −2.3±2.24 | −2.5±2.12 | −0.9±1.59 | −2.9±2.14 | −0.5±2.63 |

| Week 104 | −3.2±3.20 | −2.6±2.23 | −2.7±2.07 | −1.7±2.19 | −2.9±2.21 | −1.2±2.64 |

| Change in BASMI§ | ||||||

| Week 52 | −0.7±0.87 | −0.8±0.90 | −0.7±0.90 | −0.4±0.79 | −0.7±0.88 | 0.0±1.07 |

| Week 76 | −0.7±0.96 | −0.7±0.94 | −0.8±0.78 | −0.4±0.92 | −0.7±0.88 | −0.2±0.92 |

| Week 104 | −0.6±1.04 | −0.8±0.95 | −0.8±0.79 | −0.4±0.98 | −0.8±0.96 | −0.3±0.86 |

| Change in SF-36 PCS¶ | ||||||

| Week 52 | 12.3±8.78 | 14.1±9.40 | 12.8±10.63 | 4.8±8.96 | 13.0±8.14 | 5.4±8.62 |

| Week 76 | 12.7±10.87 | 15.2±8.65 | 13.4±10.70 | 7.3±10.82 | 13.5±8.73 | 6.6±7.49 |

| Week 104 | 13.6±7.80 | 15.5±9.32 | 14.2±11.28 | 7.6±8.83 | 13.9±9.28 | 6.5±7.77 |

| Change in SF-36 MCS¶ | ||||||

| Week 52 | 4.3±11.51 | 3.7±8.80 | 3.7±7.90 | 1.8±9.80 | 6.4±11.75 | 1.3±9.93 |

| Week 76 | 3.9±12.27 | 3.9±9.12 | 2.9±9.00 | 1.2±8.58 | 7.3±10.81 | 2.8±11.26 |

| Week 104 | 5.2±10.94 | 2.0±9.55 | 3.8±8.75 | 1.5±13.82 | 7.6±10.86 | 5.0±9.86 |

Values are mean±SD change from baseline for continuous outcomes or n (%) of patients achieving the end point for dichotomous outcomes.

Patients in these groups met the early escape criteria at week 16.

Patients in this group did not discontinue study agent prior to week 24 and crossed over at week 24.

Patients in these groups did not meet the early escape criteria at week 16.

Negative change indicates improvement.

Positive change indicates improvement.

ASAS, Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36, 36-item Short-Form health survey.

Results

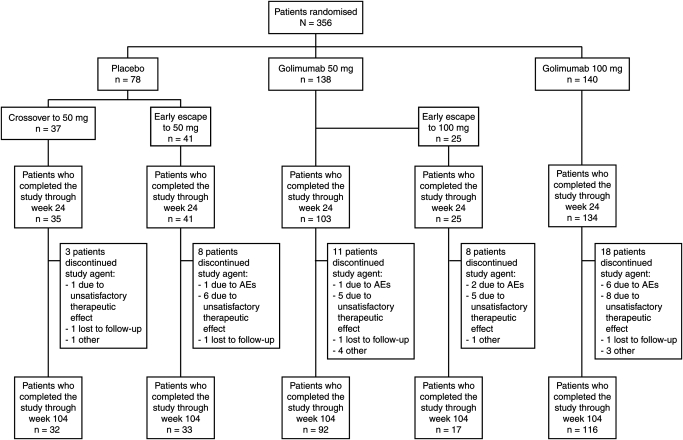

A total of 356 patients were randomly assigned to treatment (figure 2). Baseline disease characteristics of the study population and patient disposition through week 24 have been previously published.1 At baseline, 28 (35.9%) patients in group 1, 43 (29.1%) patients in group 2 and 44 (31.4%) patients in group 3 used concomitant DMARDs. At week 52, a total of 313 patients (group 1, n=70; group 2, n=118; group 3, n=125) were still receiving treatment, and 290 patients (group 1, n=65; group 2, n=109; group 3, n=116) completed the study through week 104.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition through week 104. AEs, adverse events.

At week 16, 41 (53%) patients in group 1 and 25 (18%) patients in group 2 had less than 20% improvement in total back pain and morning stiffness and entered early escape. Thirty-three (24%) patients in group 3 met the criteria for early escape at week 16, but as specified in the protocol, they did not have their dose adjusted.

Through week 104, 13 (17%) patients in group 1, 28 (20%) patients in group 2 and 24 (17%) patients in group 3 discontinued treatment. The most common reasons for discontinuation of the study agent were unsatisfactory therapeutic effect (27 patients: 8 in group 1, 11 in group 2 and 8 in group 3) and adverse events (19 patients: 2 in group 1, 7 in group 2 and 10 in group 3).

Efficacy

The intention to treat analysis revealed that 38.5% of patients in group 1, 60.1% in group 2 and 71.4% in group 3 had an ASAS20 response at week 104. In addition, 38.5% of patients in group 1, 55.8% in group 2 and 54.3% in group 3 had an ASAS40 response, and 21.8%, 31.9% and 30.7%, respectively, were in partial remission.

Actual observed efficacy outcomes at weeks 28, 52 and 104, without data imputation, are summarised in table 1 according to early escape status. Patients who required early escape at week 16 generally had lower response rates than those in the same group who did not require early escape. However, of the patients in group 2 who met the early escape criteria, 42.9% and 43.8% achieved ASAS20 responses at weeks 52 and 104, respectively, after receiving a dose escalation from 50 to 100 mg (table 1). Of the patients in group 3 who met the early escape criteria, 35.7% and 56.0% achieved ASAS20 responses at weeks 52 and 104, respectively, even though they did not receive dose adjustments.

The proportions of patients with ASDAS scores <1.1 or <2.1 at week 24, 52 or 104 are summarised according to the original randomised treatment groups (table S1). Significantly greater proportions of patients in group 2 and group 3 had ASDAS scores <1.1 or <2.1 at week 24 when compared with patients in group 1.

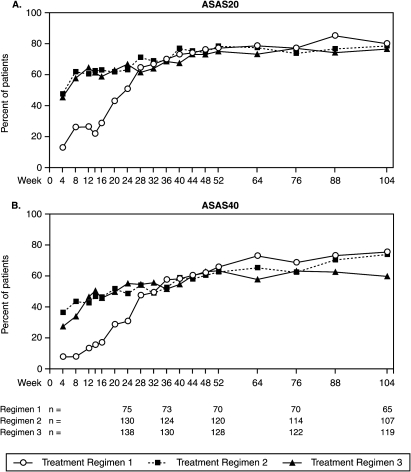

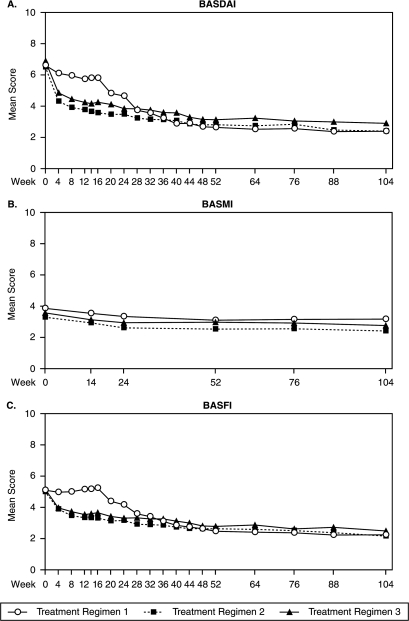

Observed ASAS20 and ASAS40 responses for each treatment regimen over time through week 104 are shown in figure 3. Mean BASDAI, BASMI (range of motion) and BASFI values over time through week 104 are shown in figure 4. By week 104, all treatment regimens led to mean BASDAI and BASFI scores that were less than 3. However, scores were reduced earlier in patients who were originally treated with golimumab from week 0 compared with those who initially received placebo and later crossed over to golimumab. Similarly, the mean BASMI score improved to less than 3 at week 104 for patients who received golimumab from week 0 through week 104, compared with a mean BASMI score of 3.17 for those patients who were assigned to placebo initially and who later entered early escape or crossed over to golimumab.

Figure 3.

The proportions of patients who had an ASAS20 or ASAS40 response through week 104. Treatment regimen 1 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to placebo at baseline and either entered early escape at week 16 to receive golimumab 50 mg through week 104 or crossed over at week 24 to receive golimumab 50 mg through week 104. Treatment regimen 2 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to golimumab 50 mg at baseline and either entered early escape at week 16 to receive golimumab 100 mg through week 104 or continued 50 mg through week 104. Treatment regimen 3 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to golimumab 100 mg at baseline and did not receive study medication adjustments. Observed data are presented without imputation. ASAS20, at least 20% improvement in the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria; ASAS40, at least 40% improvement in the criteria.

Figure 4.

Mean BASDAI, BASMI and BASFI scores through week 104. Treatment regimen 1 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to placebo at baseline and who either entered early escape at week 16 to receive golimumab 50 mg through week 104 or crossed over at week 24 to receive golimumab 50 mg through week 104. Treatment regimen 2 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to golimumab 50 mg at baseline and who either entered early escape at week 16 to receive golimumab 100 mg through week 104 or continued 50 mg through week 104. Treatment regimen 3 consisted of patients who were originally assigned to golimumab 100 mg at baseline and who did not receive study medication adjustments. Observed data are presented without imputation. BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index.

Observed proportions of patients achieving a BASDAI50 response, as well as actual changes from baseline in BASFI, BASMI (linear method) and PCS and MCS scores of the SF-36 (health-related quality of life) are summarised in table 1 for patients in each group according to their early escape status. Consistent with clinical efficacy as assessed by ASAS response criteria, patients who required early escape at week 16 generally had lower response rates or less improvement from baseline than those in the same group who did not require early escape.

Safety

Safety results through week 24 were previously reported.1 Adverse events from baseline through week 104 for patients who received at least one dose of golimumab are summarised in table 2. Adverse events were attributed to the dose that the patients were receiving at the time of the event. Thus, patients are counted in the treatment group in which they were assigned at the time of the event. The proportions of patients with at least one adverse event generally increased with longer average duration of follow-up. More patients who received the 100 mg dose of golimumab at any point during the trial had one or more serious adverse events (24 [14.5%] of 165) and serious infections (7 [4.2%] of 165) compared with patients who received golimumab 50 mg (16 [8.0%] of 213 and 3 [1.4%] of 213, respectively).

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events through week 104*

| Placebo → golimumab 50 mg (group 1) | Golimumab 50 mg (group 2) | Golimumab 100 mg (group 3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early escape (week 16–104)† | Crossover (week 24–104)‡ | 50 mg only§ | Early escape (50 mg →100 mg)† | 100 mg¶ | All golimumab | |

| Patients treated with golimumab | 41 | 34 | 138 | 25 | 140 | 353 |

| Mean duration of follow-up (weeks) | 79.0 | 77.6 | 79.2 | 72.0 | 95.9 | 90.7 |

| Mean exposure (number of administrations) | 19.1 | 18.6 | 19.2 | 17.1 | 23.0 | 21.8 |

| Patients with one or more adverse events | 36 (87.8) | 29 (85.3) | 130 (94.2) | 23 (92.0) | 135 (96.4) | 332 (94.1) |

| Patients with one or more serious adverse events | 4 (9.8) | 2 (5.9) | 10 (7.2) | 3 (12.0) | 21 (15.0) | 40 (11.3) |

| Patients who discontinued study agent due to an adverse event | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.3) | 2 (8.0) | 10 (7.1) | 19 (5.4) |

| Patients with one or more infections | 28 (68.3) | 10 (29.4) | 90 (65.2) | 17 (68.0) | 101 (72.1) | 241 (68.3) |

| Patients with one or more serious infections | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (4.0) | 6 (4.3) | 11 (3.1) |

| Patients with one or more injection-site reactions to golimumab | 3 (7.3) | 3 (8.8) | 11 (8.0) | 6 (24.0) | 16 (11.4) | 38 (10.8) |

| Injections with one or more injection-site reactions to golimumab | 3/784 (0.4) | 19/634 (3.0) | 16/2640 (0.6) | 29/427 (6.8) | 39/3220 (1.2) | 106/7705 (1.4) |

| Patients with one or more malignancies | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| Patients with markedly abnormal**: | ||||||

| Alanine aminotransferase | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.0) | 10 (2.8) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.9) | 5 (1.4) |

| Total bilirubin | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.1) | 8 (2.3) |

| Patients negative for antinuclear antibodies at baseline | 31 | 27 | 80 | 14 | 90 | 232 |

| Patients positive for antinuclear antibodies at week 104 | 1 (3.2) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (7.1) | 5 (5.6) | 11 (4.7) |

| Patients positive for anti-double-stranded DNA at week 104 | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

Patients are counted in the dosing group in which they were assigned at the time of the event.

Patients in these groups met the early escape criteria at week 16.

Patients in this group did not discontinue study agent prior to week 24 and crossed over at week 24.

This group included patients randomised to golimumab 50 mg irrespective of early escape status. Adverse events for patients who met early escape are only counted up to week 16.

This group included all patients randomised to golimumab 100 mg.

Predefined as postbaseline values of ≥2 times the baseline value and >150 IU/mL (alanine/aspartate aminotransferase) or ≥2 times the baseline value and >1.5 mg/dl (total bilirubin).

Through week 104, infections were reported in 37.7% of patients who had received placebo, 62.0% of those who had received golimumab 50 mg and 70.9% of those who had received golimumab 100 mg; serious infections were reported in 1.3%, 1.4% and 4.2% of patients, respectively (table S2). The incidence of infections per 100 patient-years in patients receiving golimumab 50 mg was similar to that for patients receiving placebo. A dose-dependent trend in the rate of infections and serious infections was noted for the two golimumab doses. However, when comparing the incidence per 100 patient-years of infection, serious infection or upper respiratory tract infection, the 95% CIs for the two golimumab doses overlapped and thus showed no apparent dose effect.

No patients died through week 104 of the study. Serious infections were similar in nature and frequency to those observed in the first 24 weeks of the study. Serious infections that occurred after week 24 included the following events: urosepsis and clostridial infection in group 1 (one patient each); tonsillitis (one patient) and anal abscess (two events in one patient) in group 2; and infectious bursitis, cellulitis, Lyme disease and pulmonary tuberculosis (one patient for each event) and pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis of the appendix (both in the same patient) in group 3. The patient with tuberculosis was negative at screening according to QuantiFERON and tuberculin testing. No opportunistic infections were reported through week 104. However, one patient in group 2 had coccidiomycosis after week 104.

As previously noted,1 two patients, one each from groups 1 and 3, had basal cell carcinoma reported prior to week 24. No additional malignancies were reported past week 24.

Injection-site reactions occurred in 7.3% of patients in group 1 who entered early escape, 8.8% of patients in group 1 who crossed over to active treatment at week 24, 24.0% of patients in group 2 who entered early escape, 8.0% of patients in group 2 who did not enter early escape and 11.4% of patients in group 3 (table 2) and mostly comprised injection-site erythema and swelling. No injection-site reactions were considered to be serious or resulted in discontinuation of study agent.

Liver enzyme elevations were more common in patients who received golimumab 100 mg than in those who received the 50 mg dose. While 2.8% of all patients had markedly abnormal elevations of alanine aminotransferase levels, no patient had concomitant markedly abnormal postbaseline elevations of alanine/aspartate aminotransferase (at least three times the upper limit of normal) and total bilirubin (at least two times the upper limit of normal).

Ten patients were found to be positive for antibodies to golimumab through week 24. Of these, five (50%) patients changed from positive to negative between weeks 24 and 104. It is unclear if antibodies to golimumab had an effect on treatment response.

Discussion

The 2-year results of the GO-RAISE trial indicate that the improvements in signs and symptoms, physical function, range of motion and health-related quality of life achieved at week 241 by patients with AS who received golimumab were sustained or improved through week 104. This was demonstrated even by the conservative analysis in which patients who met various treatment failure criteria, including early escape, were considered to be non-responders throughout the remainder of the study. Improvement was generally similar between the two golimumab doses for the end points assessed.

In addition to the original treatment assignments, the study protocol included treatment adjustments at week 16 based on patients' improvement in the total back pain score and morning stiffness (ie, early escape) that included crossover from placebo to active treatment or dose escalation from 50 to 100 mg. The findings showed that among patients who received golimumab from the beginning of the study and who did not meet the early escape criteria, greater proportions achieved ASAS20, ASAS40 and BASDAI50 responses, and improvements in BASFI, BASMI, and PCS and MCS scores of the SF-36 (health-related quality of life) were greater than those in patients who required early crossover or dose escalation. Furthermore, an increase in golimumab dose from 50 to 100 mg in group 2 patients who entered early escape did not appear to substantially increase response rates in this subset of patients. Thus, given the consistency of these findings across parameters, patients who required early escape may have had more refractory disease. Another implication of this finding is that patients with AS who do not improve by even 20% in total back pain score and morning stiffness after 16 weeks of treatment may have a reduced likelihood of responding to continued golimumab treatment.

As expected, patients in group 1 who received placebo during the first part of the study were more likely to require early escape at week 16 than those in the other groups. Patients in this group who entered early escape at week 16 or subsequently crossed over to golimumab 50 mg at week 24 demonstrated patterns of response after receiving active treatment that were similar to those observed in patients initially randomised to golimumab. Of the few patients who required early escape in group 2 (golimumab 50 mg), almost half (44%) achieved an ASAS20 response at week 104. However, the benefit of dose escalation from golimumab 50 mg to 100 mg cannot be fully elucidated from this study because there was no comparison with patients who met the criteria for early escape but remained on golimumab 50 mg. The proportion of patients in group 3 (golimumab 100 mg) who met the criteria for early escape at week 16 was similar to that of group 2, as were the ASAS20 response rates at week 104 for both early escape subgroups.

Safety results through week 104 were similar to those through week 24 in that golimumab was generally well tolerated, and adverse event patterns were consistent with the known safety profile of TNF inhibitors. The increased rate of serious infections with the 100 mg dose of golimumab in this study is consistent with results of previous studies of TNF inhibitors in which patients receiving higher doses had a greater risk of serious infections compared with patients receiving lower doses.10 11 Although patients with active AS may derive additional benefit from the 100 mg dose, the possibly increased risk of serious infections compared with the 50 mg dose should be considered.

This analysis was limited by the lack of a placebo comparator group after week 24; because of the placebo crossover, all patients received blinded, active treatment from week 24 to 104. In addition, because of the long-term nature of the study, approximately 19% of patients discontinued treatment by week 104, with unsatisfactory therapeutic effect and adverse events being the most common reasons for discontinuation. However, 290 patients completed the study through week 104 and were included in the results presented here.

The results of this study suggest that subcutaneous injections of golimumab every 4 weeks were effective in reducing the signs and symptoms of AS in patients with active disease despite prior treatment with NSAIDs or DMARDs, as well as in sustaining improvement in physical function, range of motion and health-related quality of life through week 104. Patients who completed the 2-year study will continue to be followed for up to 5 years to allow for a long-term analysis of the effects of golimumab in patients with AS. In addition, the effect of golimumab on radiographic end points including MRI was also evaluated, and these results will be reported separately. The sustained improvement in the signs and symptoms of AS in the current analysis is consistent with 2-year studies of other anti-TNF agents,12–14 and the safety profile of golimumab appeared to be consistent with the known safety profile of TNF inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, the investigators and the study personnel who made this trial possible. The authors also thank Michelle Perate, MS, Rebecca Clemente, PhD, and Mary Whitman, PhD, of Janssen Biotech, Inc, L.L.C., a wholly owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, Inc., who helped prepare the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding This study was funded by Centocor Research & Development, a division of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C., and Schering-Plough Research Institute, Inc.

Competing interests Dr Braun has received honoraria for talks, advisory boards and grants for studies from Centocor Research & Development, Celltrion, Amgen, Abbott, Roche, BMS, Novartis, Pfizer (Wyeth), MSD (Schering-Plough), Sanofi-Aventis and UCB. Dr Deodhar has received payments for educational lectures, teleconferences and serving on advisory boards for Centocor Research & Development. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by OHSU. Dr Inman has received consulting fees from Merck, Schering-Plough, Abbott, Amgen and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr van der Heijde has received consulting fees and/or research grants from Abbott, Amgen, BMS, Centocor R&D, Chugai, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB and Wyeth. Drs Mack and Hsu and Mr Xu are employees of Centocor Research & Development, a division of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C., and own stock and/or stock options in Johnson & Johnson, Inc.

Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each site.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Inman RD, Davis JC, Jr, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3402–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kay J, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B, et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite treatment with methotrexate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:964–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC, et al. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The Bath AS Metrology Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1694–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Feldtkeller E. Proposal of a linear definition of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) and comparison with the 2-step and 10-step definitions. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:489–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006;295:2275–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westhovens R, Yocum D, Han J, et al. The safety of infliximab, combined with background treatments, among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and various comorbidities: a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1075–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Two year maintenance of efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:229–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dijkmans B, Emery P, Hakala M, et al. Etanercept in the longterm treatment of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1256–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Heijde D, Schiff MH, Sieper J, et al. Adalimumab effectiveness for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis is maintained for up to 2 years: long-term results from the ATLAS trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:922–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]