Summary

Many classifications of the cerebral venous system are found in the literature but they are seldom based on phylogenic study. Among vertebrates, venous drainage of the brain vesicles differs depending on the species. Due to the variability, poorly descriptive articles, and many different names used for the veins, the comparative study of the cranial venous system can hardly be performed in detail. The cranial venous system in vertebrates can be divided into three systems based on the evolution of the meninges and structures of the brain vesicles: the dorsal, lateral-ventral and ventricular systems.

This study proposes a new classification of the venous drainage of brain vesicles using knowledge from a comparative study of vertebrates and focusing on the dorsal venous system. We found that the venous drainage of the neopallium and neocerebellum is involved with this system which may be a recent acquisition of cranial venous evolution.

Key words: classification, cranial venous system, comparative anatomy, vertebrates

General Introduction

The vertebrate circulatory system not only shows a difference between the anatomy and function of the arterial and venous system, but molecular differences can also be demonstrated between arterial and venous endothelial cells before blood vessels are formed 1.

Classifications of the intracranial venous system are found in the literature, but most of them are based on the cerebral venous anatomy of humans 2,3. Cerebral venous variations are also reported. Some of them can be elucidated using ontogenetic viewpoints. Nevertheless, an explanation using the phylogenic evolution of the cranial venous system has been poorly discussed.

Like phylogenic ascent, the venous system of the brain vesicles among vertebrates has been modified and relocated according to the evolution of the pallia, deep nuclei and cerebellum. This study devises a new classification of patterns of cranial venous system and focuses on the evolution of the dorsal venous system among vertebrates, which is associated with the development of the neopallium and neocerebellum.

Material and Methods

Literature on the cranial venous anatomy in vertebrates was reviewed. Using the area of venous drainage, the veins involved and their functions, we classify the cranial venous system in vertebrates into three systems compared to the venous drainage of the five brain vesicles in man. The vertebrates reviewed are fish (Myxine glutinosa, Eptatretus stouti, and Danio rerio), amphibians (Amblystoma tigerinum), reptiles (Testudo geometrica), birds (Larus argentatus and Light Sussex birds), rodents (inbred Sprague-Dawley strain of rats), opossums (Didelphis virginiana), domestic animals (dogs, cats, rabbits, pigs, horses, oxen, sheep and goats), primates (Macaca mulatta, Cebus paella, Papio ursinus, Cercopithecus pygerithrus, Galago senegalensis) and hominids.

Short messages from comparing five brain vesicles and spinal cord anatomy4-6

The brain of the early embryo and of lower vertebrates is all in one plane and almost in a straight line, but that of adult higher vertebrates becomes progressively folded. In the evolution from quadrupedal mammals to bipedal humans, the brain stem has gradually shifted from horizontal with the cerebrum to a nearly vertical position through the foramen magnum. The cerebral cortex is a relatively recent acquisition.

The telencephalon. The archipallium is often considered continguous with the olfactory cortex, but the extent of the archipallium varies among species. The olfactory lobes are very large in lower vertebrates, but their relative size decreases steadily as other parts of the brain become progressively larger. The telencephalic vesicles (cerebral hemispheres) begin to develop in fish which have the cerebrum made of the archipallium. Amphibians develop the archipallium and paleopallium. In reptiles, the median dorsal portion broadens out to form the primitive neopallium between the archi- and paleopallium. With marked development of the neopallium, the two more primitive ones are finally pushed medially. In man, the archipallium makes up the hippocampus, whereas the paleopallium consists of the parahippocampal gyrus and the primary and secondary olfactory cortices. The growth of the neopallium is also responsible for a change in shape of the other areas, since when the occipital lobe is developed, the archi- and paleopallium are pushed posteriorly, and eventually with the development of a temporal lobe, anteriorly again and ventrally as seen in most mammals, especially in man.

The cerebral hemispheres of mammals are connected by three commissures: anterior and hippocampal commisures connect the olfactory portion of the two hemispheres, and the large corpus callosum connects the neopallium (nonolfactory parts). The corpus callosum appears in mammals owing to the development of the abundant interhemispheral association fibers.

A primodial pallidum is found in primitive vertebrates. The development of the caudate nucleus and putamen (neostriatum) parallels the development of the thalamus and neopallium. This structure first appeared in reptiles, and is well-developed from birds onward.

The diencephalon. The diencephalon of vertebrates from fish to mammals consists of the same three major components: epithalamus, thalamus and hypothalamus.

The mesencephalon. The tectum displays a pair of prominent "optic lobes" or superior colliculi and, caudally, "auditory lobes" or inferior colliculi in all vertebrates. The superior colliculi are especially large in birds. The inferior colliculi are prominent in reptiles.

The metencephalon. The pons has two portions which reflect its phylogenic development, an older tegmentum lying in the floor of the 4th ventricle, and a more recent acquisition, the ventral portion. The cerebellum increases considerably in size in the phylogenic ascent of vertebrates. Petromyzonts have only a primodial cerebellum (auricles) which is homologous with the flocculi and nodules of higher vertebrates. In bony fish, the auricles are also present. The corpus of cerebellum, which is a homolog of the vermis, becomes developed in these animals as in frogs. In reptiles, the corpus of the cerebellum has medial and lateral portions which correspond to the vermis, and the primodium of the paravermal part of the cerebellar hemisphere, respectively. The cerebellum of birds is similar to that of reptiles but it is larger and has more folia.

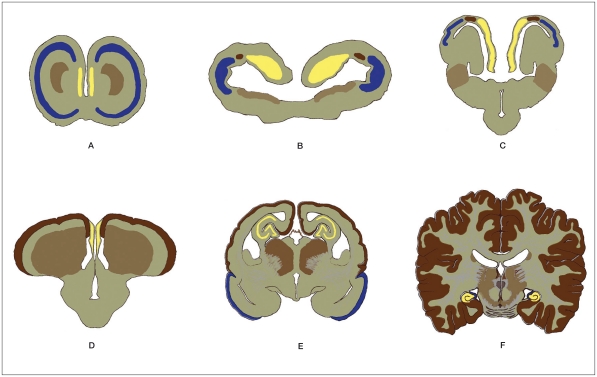

Figure 1.

The evolution of the pallia of the brain. A; Hagfish, B; Urodele, C; Turtle, D; Bird, E; Opossum, F; Human (After Elizabeth C.Crosby8 with modification) yellow; Archipallium, blue; Paleopallium, dark brown; Neopallium, light brown; Striatum.

The myelencephalon. There are no obvious differences in terms of gross morphology of the medulla among vertebrates.

In fish, ten pairs of cranial nerves are identified. In mammals, these ten cranial nerves have similar relations both centrally and peripherally. But the mammalian brain has incorporated a part of the neural tube which in primitive fish was an unmodified spinal cord. The first ten cranial nerves are homologous with those of fish and the last two represent a modification of nerves which in fish were the anterior spinal nerves.

The spinal cord. In cyclostomes, the gray matter of the cord is a solid mass with no dorsal or ventral horns. In fish, the gray matter has dorsal and ventral columns but the dorsal column is a solid mass. The cord of the urodeles resembles that of fish but that of salientiens shows cervical and lumbar enlargement for the first time. For reptiles, the cord resembles that of mammals. Reptiles with well-developed appendages have cervical and lumbar enlargement but none is found in snakes. In birds, the gray matter is differentiated like that of mammals.

Results

The development of the cranial venous system among vertebrates is quite similar in having a primary head vein in the embryonic period. But after maturation, it differs depending on each species. Most of the neural tube is covered by a primitive capillary plexus, which is drained by three well defined veins or stems into the more superficially placed primary head vein (figure 2).

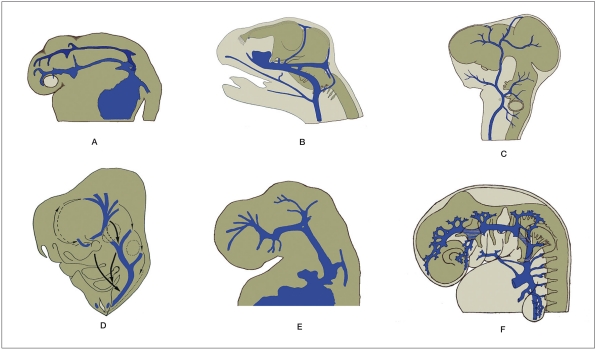

Figure 2.

Illustration shows similar development of the primary head vein in fish, reptile, bird, rat, calf and man, respectively. A) A 28 hour-old zebrafish embryo. B) A late embryo of Tropidonotus natrix. C) A herring gull embryo after 5-6 days of incubation. D) A rat embryo on day E12-17. E) A 5 week-old calf. F) A 5 mm long human embryo. (Modified from 9-14).

Proposed classifications of cranial venous system in vertebrates

Using the comparative anatomy of the cranial venous patterns in difference species of vertebrates and areas of the venous drainage, we can organize a new system of the venous drainage patterns of the five brain vesicles into three different systems (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

The terms of the cortical derivatives and their areas involved7.

| Pallium | Area involved |

|---|---|

| archipallium | the hippocampal formation, the dentate gyrus, the fasciolar gyrus, the indusium griseum (supracallosal gyrus) |

| paleopallium (rhinencephalon) |

the olfactory bulb, tract, tubercle and striae, the anterior olfactory nucleus, parts of the prepyriform cortex |

| neopallium | others of the cerebral cortices |

Table 2.

Proposed classifications of prosencephalic venous drainage patterns (supratentorial) in vertebrates, their related palliums and venous structures.

| Venous System |

Related area |

Venous structures compare to man |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal venous system |

Neocerebellum | SSS, ISS, Str-S, FS, TS |

|||||||

| Lateral- Ventral venous system |

Paleopallium | Tentorial sinus (middle cerebral vein) |

|||||||

| Archipallium | Basal vein of Rosenthal |

||||||||

| "Ventricular system" |

lateral and 3rd ventricles |

Tributaries of the forerunner of the median prosencephalic vein of Markowski |

|||||||

|

SSS, superior sagittal sinus; ISS, inferior sagittal sinus; Str-S, straight sinus; FS, falcine sinus; TS, transverse sinus; ICV, internal cerebral veins | |||||||||

Table 3.

Proposed classification of mesencephalic and rhombencephalic venous drainage patterns (infratentorial) in vertebrates, their related parts of drainage and venous structures.

| Venous System |

Related cerebellum and brain stem |

Venous structures compare to man |

|---|---|---|

| Dorsal venous system |

Neocerebellum | TS, OS, MS, |

| Lateral- Ventral venous system |

Archicerebellum, Cerebellar peduncles, Choroid plexus of 4th ventricle, Brain stem |

mesencephalic pontine medullary veins, veins of cerebellopontine fissure |

| "Ventricular system" |

Paleocerebellum, tectum of the midbrain |

paracentral and superior vermian veins, tectal vein |

|

TS, transverse sinuses; OS, occipital sinuses; MS, marginal sinuses | ||

Table 4.

The dorsal venous system in difference species of vertebrates and its outlets.

| SSS | TS | PSS | Str-S | SS | OM | IJV | EJV | VP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fishes | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Amphibians | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Reptiles | +a | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Birds | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| Domestic animals | + | + | + | +/−b | − | − | −a | + | + |

| Monkeys | + | + | + | + | + | +b | + | + | + |

| Hominids | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | + | +b | + | N/A | N/A |

| Man | + | + | −c | + | + | −d | + | − | + |

|

SSS, superior sagittal sinus; TS, transverse sinus; PSS, petrosquamosal sinus; Str-S, straight sinus; SS, sigmoid sinus; OM, occipital-marginal system; IJV, internal jugular vein; EJV, external jugular vein; VP, vertebral venous plexus A) It does not have a major role of venous drainage of brain vesicles. B) Depending on species. C) Rare case reports30,31. D) Except for neonates, infants, and some adults. | |||||||||

Submammals

Fish

Cecon et Al18 studied the brain of Myxine glutinosa and Eptatretus stouti by scanning electron microscopy of microvascular casts. The study showed that all cerebral veins lie superficially and ascend from ventral and lateral brain territories.

The veins drain exclusively into the dorsally located large "sagittal sinus". However, the meninges in fish do not develop as well as those in mammals. Therefore, we will use sagittal "vein" instead of "sinus" because they did not describe the layer of the meninges where the veins are located.

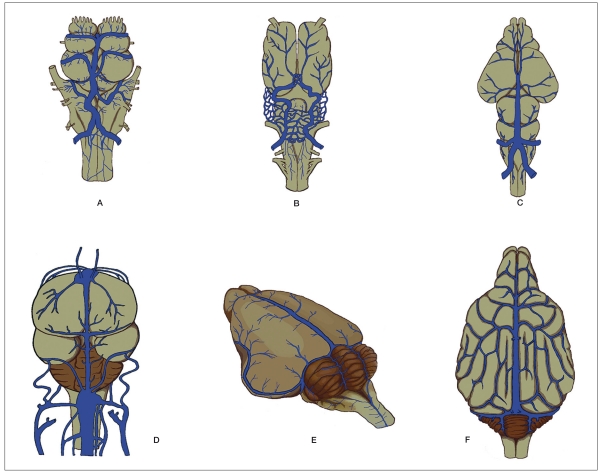

Figure 3.

Dorsal located veins or sinuses in different adult vertebrates. Even though the mid-dorsal located vein or sinus seems to be similar among vertebrates, the evolution and function are different depending on the species. A) Hagfish. B) Amblytoma tigerinum. C) Testudo geometrica. D) Light Sussex bird. E) Guinea pig. F) Dog. (Modified from15-20).

The sagittal vein forms rostrally from the "middle olfactory vein" and the "lateral olfactory vein" which drain blood from olfactory bulbs and anterior part of the telencephalon, and receives the "anterior and middle cerebral veins" and then, the "rhombencephalic vein". It lies on the mid-sagittal plane along the dorsal aspect of the brain vesicles and splits into the right and left "posterior cerebral veins" at the caudal end of the medulla, which leave the brain capsule and become the cardinal veins. The venous drainage pattern of all of the brain vesicles is dorsally oriented.

Amphibians

Roofe16 studied the endocranial blood vessels of Amblytoma tigerinum. The study showed very thin "vena medialis durae" and "vena lateralis medialis durae" which are located in the dura mater on the dorsal, mid-sagittal plane of the telencephalon. They empty into the "nodus vasculosus" which is a dense rete of venous sinusoid structures located next to the paraphysis. The blood is then discharged further into the "oblique sinuses''.

They are the pair dural sinuses for flow of blood from the "nodus vasculosus" to the rete of the "saccus endolymphaticus" and to the internal jugular vein respectively. The pattern of venous drainage is dorsally oriented as in hagfish.

The dural veins described do not play a major role in draining the blood from the telencephalon. The "dorsal pallium" (primitive neopallium) is, in fact, drained by the "vena hemisphaerii posterior" which may discharge either into the "oblique sinus" or the rete of the "saccus endolymphaticus. It is located on the dorsolateral surface of the hemisphere.

Reptiles

Schepers et Al 15 described the venous system of the Testudo geometrica. The veins are not sinusoidal in character as in Amblytoma tigerinum. The large "dorsal longitudinal vein" lying in the arachnoidal spaces was confirmed on histological examination. All endocranial veins are comparable with the intermeningeal veins of fish. Peridural vessels can be identified but they are diminutive. The "anastomotic vein'' unites the "dorsal longitudinal vein" with the extracranial vein. It courses between the trigeminal and facial nerves, and then leaves the cranial cavity. No evidence of dural venous sinuses is shown in the Tortoise brain.

Birds

The dural venous sinuses become prominent in birds and mammals. We found that the development of the neopallium in birds occurs along with the cranial venous sinuses, well-developed meninges and arachnoid villi.

Richards 20 showed that the comparable superior sagittal sinus, "mid-dorsal sinus", receives venous blood from the olfactory area, communicates with the anterior part of the ophthalmic system and drains the area of the forebrain and choroid plexus. It continues with the comparable transverse sinus, "anterior cerebral vein", and the occipital sinus. The "anterior cerebral vein" runs between the forebrain and cerebellum, enters the "temporal rete" which is the extracranial venous plexus on the temporal area. The major blood drains through the occipital sinus and exits the cranium by way of the vertebral veins. The homologue of internal jugular vein, "the posterior cephalic vein", is quite small compared to the vertebral veins.

Mammals

Rats

In rats 21,22, the pattern of the dorsal venous system is quite similar to that of man. The superior sagittal sinus, the straight sinus and the transverse sinuses join together at the torcular herophilli. The difference is that the transverse sinus runs laterally between the attached edges of the tentorium cerebelli and branches near the petrosquamosal fissure into the dorsally directed sigmoid sinus and the laterally directed "petroquamosal sinus". The petrosquamosal sinus emerges through the wide petrosquamosal fissure to run extracranially between it and the temporomandibular joint and finally empties into the external jugular vein. The minor venous blood is drained by the sigmoid sinus which opens into the tiny internal jugular vein and anastomoses with the vertebral venous plexus.

Domestic animals19,23,24

It is interesting to note that the internal jugular veins in domestic animals are quite small and non-dominant compared to the external jugular veins and vertebral venous plexus. The dorsal venous system of rats and this animal group is quite similar. The transverse sinus receives major venous blood from the brain and leaves the cranium through the same foramen. Another significant pathway of venous blood draining is the vertebral venous plexus. The sigmoid sinus in domestic animals is different from that in man. It passes through the bony canal and opens in the internal vertebral venous plexus.

The veins lying on the dorsal surface of the cerebellum in the groove between the vermis and the hemispheres, "the dorsal cerebellar veins", in sheep, dogs and oxen drain the dorsal surface of the cerebellum and empty into either the confluence of sinuses, the occipital sinuses, or the transverse sinuses. The pattern of the dorsal venous sinuses in camels is quite similar to those of domestic animals 25.

Monkeys26,27

Primates have the pattern of intracranial venous drainage in between domestic animals and man. They have both internal and external jugular veins dominant.

The dorsal venous system in tufted capuchins, rhesus monkeys, vervet monkeys, bushbabies, and baboons is similar to man except for the presence of a prominent pretrosquamosal sinus which empties into the external jugular vein.

The occipital-marginal system varies among species. The occipital sinus is absent in rhesus monkeys whereas it is present in pairs in baboons, vervet monkeys and bushbabies.

Hominids

Falk28 studied fossil hominid skulls and found that the early bipeds (Australopithecus afarensis) and robust australopithecines are characterized by a very high frequency of an enlarged occipital-marginal sinus system. She stated that selection for bipedalism was related to the epigenetic adaptations of the circulatory system for emptying blood into the vertebral venous plexus, since the occipital-marginal sinus system has numerous connections with it. In robust australopithecines, the transverse sinuses may be reduced or even missing. The initial selection for bipedalism related to a dominant occipital-marginal system in some hominids described above was relaxed in the other subsequent hominids. The decrease in the frequency of the system coincided with an increase in the frequency of other routes for discharging venous blood into the vertebral venous plexus, the foramina which conduct emissary veins.

Man

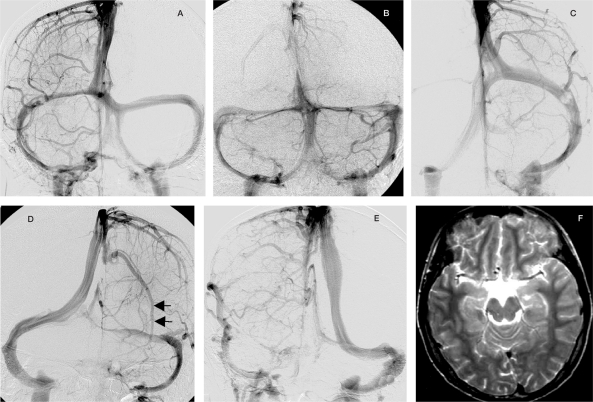

Morphological changes in the dorsal venous system in neonates after birth are the progressive jugular bulb maturation, gradually disappearance of the occipital-marginal system, the decreasing diameter of the transverse sinuses29and the disappearance of the petrosquamosal sinus30,31. The persistence of the disposition can be seen (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Some of the dorsal venous dispositions in adult man are shown. The occipital sinus can be separated (A) or single (B). The occipital-marginal system can persist as an alternative venous pathway as in hominids (C, right side). The transverse sinus is usually dominant on the right side, which receives venous blood from the superior sagittal sinus whereas the left one is usually small and collects blood from the straight sinus as described ontogenetically by Padget[10] (D), or even missing (E).The SSS can be off-midline but respecting the falx cerebri (E and F are from the same patient). When the epidural veins do not connect with the pial veins, the SSS can be missing leaving a long pial vein runing parallel before emptying into it (D, arrows).

Hypothesis of the comparative dorsal venous system anatomy

We use the term dorsal venous system because it has a special kind of evolution. We include all venous sinuses which relate to the membranous neurocranium in this category. It consists of the superior sagittal sinus (SSS), inferior sagittal sinus (ISS), straight sinus (Str-S), falcine sinus (FS), transverse sinus (TS), and occipital-marginal system (OM). The major area of venous drainage in the supratentorial compartment involves with neopallium, little if any deep nuclei, whereas in the infratentorial compartment it involves the neocerebellum.

In fish, the archipallium makes up most of the cerebrum. Amphibians develop the archipallium and paleopallium, whereas reptiles develop the archipallium, paleopallium and a primitive neopallium.

In mammals, a new processing area, the neopallium, develops between the archi- and paleopallia. Among more advanced mammals, the neopallium expands greatly. It pushes the paleopallium to the underside of the hemispheres, and the archipallium towards the midline. As these pallia expand, they move from the primitive position near to the ventricle, to a more superficial position, overgrowing the ventral basal ganglia.

There is some interesting evidence from the comparative anatomy of the meninges. In fish, the membranes surrounding the neuraxis consist of a thin, poorly differentiated vascular meninx primitiva closely investing the central nervous system, and continuous with a similar investment of the nerve roots. In amphibians, the meninx primitiva provides an outer, dense (periosteodural) layer, which becomes the dura mater, and an inner, less dense one, the meninx secundaria which later differentiates into arachnoid and pia mater in mammals. In reptiles, the dura mater is fairly well separated from the underlying arachnoid and pia mater. In birds, the meninges are rather similar to those in reptiles but they show a higher degree of differentiation. It is generally assumed that in all fish the leptomeningeal space does not contain CSF as those filled in mammals. In Hagfish, various Selachians, Osteichthyes, and Dipnoans, they lack of either direct ventricular communication with, or of significant fluid diffusion flow into, leptomeningeal spaces 32. On the basis of scattered reports, the arachnoid villi can be assumed to occur in birds 33 and mammals. They can be found along large intracranial veins and venous sinuses, especially on the dorsal and some parts of the lateral venous system.

Having looked at the evolution of the meninges and arachnoid villi, along with the evolution of the neopallium and the role of CSF absorption, it can be assumed that the dorsal venous system and some parts of the lateral venous group are found only in higher vertebrates.

The evolution of the dorsal venous system shows that in fish, amphibians and reptiles most of the venous blood from the telencephalon is drained dorsally into the dorsal sagittal vein which is located in the intermeningeal space. The dural veins of these animals do not have a role in draining blood from the brain. With the evolution of the peridural or epidural veins and dura matter in the higher vertebrates, it seems that the penetrating veins from the telencephalon are merged with the epidural veins to become the dural venous sinuses found from birds onward. The major role of dural venous sinuses is not only drainage of venous blood from the developing neopallium but also drainage of the CSF from the cranial cavity.

However, it seems that the large dorsal longitudinal vein in fish and reptiles would be the forerunner of the median prosencephalic vein of Markowski. The vein runs dorsally above the diencephalon, mesencephalon and metencephalon. It exits the cranial cavity along with the lower cranial nerves into the internal jugular vein.

In the Tortoise, the "anastomotic vein" constitutes an anastomosis between the dorsal longitudinal vein and the internal jugular vein outside the cranial cavity. It passes between the trigeminal and facial nerves and exits the cranial cavity. Padget10 mentioned that, in reptiles, it is the dwindling of the head sinus so that the venous blood of the brain can drain through this connection into the internal jugular vein.

Butler 34 reported that in all mammals, except Monotremes, without a caudally expanded cerebral cortex the transverse sinus retains the more vertical position relative to the skull base and consequently the petrosquamosal sinus remains as a large channel which empties into the external jugular vein through the postglenoid foramen. The foramen is located between the tympanic ring and the temporo-mandibular joint. In monotremes, the petrosquamosal sinus courses along the anterior surface of the temporal bone, runs into the facial canal and then exits the cranium through the stylomastoid foramen. Some adult animals including man have no postglenoid vein e.g. rabbits, pigs34 and cats24.

The tentorium cerebelli emerged relatively late in evolution. It is absent in fish, reptiles and amphibians. Initially when it appears in some mammals, e.g. bats, rodents and opossums, it consisted of delicate bilateral symmetrical dural folds not united in the midline. When the posterior portion of the falx cerebri became united with the tentorium cerebelli in higher vertebrates e.g. cats, dogs, goats, deer, rabbits, mink, sheep, porpoises, wallabies, dolphins, primates and man, the straight sinus was apparent. The sinus is absent in fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, bat, rodents and opossums35.

Without the tentorium cerebelli, the transverse sinus could not exist as seen in cases of parietal cephalocele with venous sinus anomaly36. Absence of the falx cerebri is also associated with no superior sagittal sinus37. These observations strongly suggest the significant effect of the falx cerebri on the development of the superior sagittal sinus, and that of the falx cerebelli on the development of the straight sinus.

We doubt that the sigmoid sinus was only the emissary vein receiving blood from the transverse sinus in the bony canal found in domestic animals19 and camels25. Therefore, we do not include the sigmoid sinus with the dorsal venous system. The sigmoid sinus is apparent in all mammals except monotremes34. It becomes dominant with phylogenic ascent. It can empty into both the vertebral venous plexus and internal jugular vein depending on each species. The vertebral venous plexus has a dominant role in draining blood from the sigmoid sinus over the internal jugular vein in rats, hedgehogs, bats and dogs.

The occipital-marginal system becomes evident from birds onward. Its dominance varies between species. In the adult Light Sussex birds 20, it is the major venous outlet of all brain vesicles to the internal vertebral veins while it is non-dominant in domestic animals. It becomes prominent in certain primates and hominids probably due to the epigenetic adaptation of the circulatory system for the upright position as mentioned.

Conclusions

This article describes the comparative cranial venous system among vertebrates with special emphasis on the dorsal venous system which is a recent acquisition in the evolution. The drawbacks of this article may stem from insufficient anatomical data due to the venous variations, different venous names, and poorly descriptive literature.

References

- 1.Jesús Torres-Vázquez MK, Weinstein BM. Molecular distinction between arteries and veins. Cell Tissue Research. 2003;314:43–59. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0771-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhoton ALJ. The cerebral veins. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(4Sup):S159–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasjaunias P, terBrugge KG, Berenstein A, editors. Clinical Vascular anatomy and Variations. 2nd ed. Vol 1. Springer; 2001. Surgical Neuroangiography. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kent CG, editor. Brain. Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates. Times Mirror/Mosby College Publishing; 1987. pp. 530–543. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montagna W. Comparative anatomy of the central nervous system. Comparative anatomy. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1959. pp. 322–339. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey B, Sarnat MGN, editors. Evolution of the Nervous System. New York: Oxford University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raymond C, Truex MBC. Human Neuroanatomy. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crosby EC, editor. Comparative Correlative Neuroanatomy of the Vertebrate Telencephalon. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabó K. The Cranial Venous System in the Rat: Anatomical Pattern and Ontogenetic Development II. Dorsal Drainage. Annals of Anatomy. 1995;177:313–322. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(11)80371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padget DH. The development of the cranial venous system in man from the viewpoint of comparative anatomy. Contribute Embryology. 1957;36:81–151. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MidtGard U. The Blood Vascular System in the Head of the Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) Journal of Morphology. 1984;179:135–152. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051790203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isogai S, Horiguchi M, Weinstein BM. The Vascular Anatomy of the Developing Zebrafish: An Atlas of Embryonic and Early Larval Development. Developmental Biology. 2001;230:278–301. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruner LH. On The Cephalic Veins and Sinuses of Reptiles, with Description of a Mechanism for Raising the Venous Blood-Pressure in the Head. American Journal of Anatomy. 1907;7(1):1–117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Stoeter DP, Voigt K. Rontgenologishe GefaBdarstellung bei Embryonen und Feten. Fortschr. Rontgenstr. 1977;126(6):581–587. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1230642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schepers GWH. The Blood Vascular System of the Brain of Testudo Geometrica. :451–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roofe PG. The Endocranial Blood Vessels of Amblystoma Tigerinum. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1934;61(2):257–293. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majewska-Michalska E. Vascularization of the brain in guinea pig.I: Gross anatomy of the arteries and veins. Folia Morphology (Warsz) 1994;53(4):249–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephan Cecon BM, Lametschwandtner A. Vascularization of the Brains of the Atlantic and Pacific Hagfishes, Myxine glutinosa and Eptatretus stouti: A Scanning Electron Microscope Study of Vascular Corrosion Casts. Journal of Morphology. 2002;253:51–63. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghoshal NG, Popesko P. The Venous Drainage of the Domestic Animals. W.B.Saunders Company; 1981. Veins of the head and neck and thoracic wall and thoracic cavity; pp. 39–93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards SA. Anatomy of the veins of the head in the domestic fowl. Journal of Zoology, London. 1968;154:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szabó K. The Cranial Venous System in the Rat: Anatomical Pattern and Ontogenetic Development II.Dorsal Drainage. Annals of Anatomy. 1995;177:313–322. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(11)80371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szabó K. The Cranial Venous System in the Rat: Anatomical Pattern and Ontogenetic Development I. Basal Drainage. Anatomy and Embryology. 1990;182:225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00185516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong LD. The Brain Venous System of the Dog. American Journal of Anatomy. 132:479–490. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001320406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barone R. Angiologie Vigot Frères. 1996. Amatomie comparée des mammifères domestiques, in Tome cinquième; pp. 480–531. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zguigal NGG. Dural Sinuses in the Camel and Their Extracranial Venous Connections. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 1991;20:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1991.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein JD., JR Studies of Intracranial and Orbital Vesculature of the Rhesus Monkey (Macaca mulatta) The Anatomical Record. 1962;144:37–41. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091440106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lake AR, NI V., Le Roux CG, Trevor-Jones TR, De Wet PD. Angiology of the brain of the baboon Papio ursinus, the vervet monkey. Cercopithecus pygerithrus, and the bushbaby Galago senegalensis. American Journal of anatomy. 1990;187(3):277–86. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001870307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falk D. Evolution of Cranial Blood Drainage in Hominids: Enlarged Occipital/Marginal Sinuses and Emissary Foramina. American Journal of Physiology Anthropology. 1986;70:311–324. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okudera T, Huang YP, Ohta T, Yokota A, Nakamura Y, Maehara F, Utsunomiya H, Uemura K, Fukasawa H. Development of Posterior Fossa Dural Sinuses, Emissary Veins, and Jugular Bulb: Morphological and Radiologic Study. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1994;15:1871–1883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chell J. The squamoso-petrous sinus: a fetal remnant. Journal of Anatomy. 1991;175:269–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsot-Dupuch MG-D, Elmaleh-Berge’s M, Bonneville F, Lasjaunias P. The petrosquamosal sinus: CT and MR finding of a rare emissary vein. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2001;22:1186–1193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhlenbeck H. In: Morphologic Pattern of the Vertebrate Neuraxis, in The central nervous system of vertebrates: a general survey of its comparative anatomy with an introduction to the pertinent fundamental biologic and logical concepts. Karger S., editor. New York: 1897. pp. 668–728. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelkenberg U. Chicken arachnoid granulations: a new model for cerebrospinal fluid absorption in man. Neuroreport. 2000;12(3):553–557. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler H. The development of mammalian dural venous sinuses with special reference to the postglenoid vein. Journal of Anatomy. 1967;102:33–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klintworth G. The Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Tentorium Cerebelli. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otsubo HS, Sato N, Ito H. Cephaloceles and abnormal venous drainage. Child’s Nervous System. 1999;15:329–332. doi: 10.1007/s003810050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasjaunias P, ter Brugge KG, Berenstein A, editors. Clinical and Interventional Aspects in Children. 2nd ed. Vol 3. Springer: 2006. Surgical Neuroangiography. [Google Scholar]