Abstract

HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects Hispanics. Our objective was to determine the risk of late diagnosis and rate of survival after HIV/AIDS diagnosis among Hispanics compared to other racial/ethnic groups. We performed a systematic review of the PubMed database for peer-reviewed articles published between January 2000 and September 2010. Primary outcomes included survival after HIV/AIDS diagnosis and delayed diagnoses. The definition of delayed diagnosis varied by study, ranging from concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis to diagnosis of AIDS within 3 years of HIV diagnosis. We found that Hispanics are at significantly greater risk for delayed diagnosis than non-Hispanic whites. Hispanic males and foreign-born Hispanics had the highest risk of late diagnosis. Available data on survival were heterogeneous, with better outcomes in some Hispanic subgroups than in others. Survival after antiretroviral initiation was similar between Hispanics and Whites. These findings emphasize the need for culturally-sensitive strategies to promote timely diagnosis of HIV infection among Hispanics and to examine the health out-comes and needs of high risk Hispanic subgroups.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, Hispanic, Delayed diagnosis, Survival rate, Mortality

Introduction

Hispanics are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS, with annual HIV incidence rates three times greater than those of non-Hispanic whites [1, 2]. Hispanics make up approximately 14% of the US population, but account for 18% of persons diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in the US [1]. Hispanics are the fastest growing minority population, and as their population expands, the absolute number of HIV/AIDS cases among is expected to also rise significantly [1-3].

In response to this need, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a summary of recommendations on the epidemic and prevention of HIV in the Hispanic community [4]. The CDC is also sponsoring the cultural adaptation and evaluation of evidence-based HIV prevention strategies developed through the Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBI) [5]. While the focus on HIV prevention is a key component in addressing disparities in HIV rates among Hispanics, an important aspect, which has received less attention, has been disparities in health outcomes among Hispanics infected with HIV. HIV/AIDS is the fourth leading cause of death among Hispanics aged 35–44, compared to being the tenth leading cause among non-Hispanic whites of the same age group [6]. In addition, rates of death among Hispanics diagnosed with HIV infection have increased from 2005 to 2008 [7]. Late diagnosis and unrecognized HIV infection appear to be important factors associated with disparities in health outcomes and HIV-related mortality.

We performed a systematic review of the literature to evaluate the risk of late presentation to HIV care and death after HIV/AIDS diagnosis among Hispanics living in the US compared to other racial and ethnic groups. We explored the hypothesis that disparities in outcomes are associated with late presentation to care by comparing survival by stage of HIV diagnosis among racial/ethnic groups.

Methods

We searched the PubMed online database for articles published between January 1, 2000 and September 30, 2010 with the following search terms: Hispanic American, Latino, HIV, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, treatment outcome, mortality, death, late presentation, delayed diagnosis, access to care, and survival. Only English language papers were reviewed. For full details on keywords and combinations used, please see Appendix 1. Of note, in this article we will use the capitalized form of “Blacks” and “Whites” to refer to non-Hispanic blacks and whites.

Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

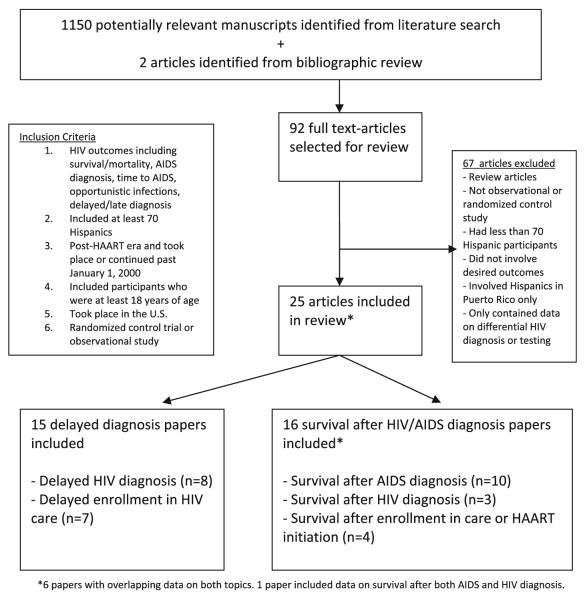

Figure 1 provides the PRISMA statement flowchart for systematic reviews [8]. The initial search identified 1,150 potential articles and two from bibliographic review. Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by two authors (NEC, KRP). For discordant selections, manuscripts were evaluated in more detail and eligibility for inclusion was determined by consensus. Publications were selected for review if (1) there were at least n = 70 HIV-infected Hispanics included in the study, (2) study participants included individuals who were at least 18 years of age, (3) the study was performed in the post-HAART era and either continued or took place after 1/1/2000, (4) the study took place in the 50 United States, (5) the study was either a randomized controlled study or an observational study, (6) the study looked at HIV outcomes including survival, mortality, delayed/late diagnosis, virologic and immunologic outcomes, AIDS diagnoses or time to AIDS. We excluded articles that looked solely at HIV prevention and testing, HIV risk behaviors, and HIV diagnoses as we were not interested in the differential rates of HIV infection, but only outcomes after HIV infection. We also excluded papers that were limited to data from Puerto Rico based on concern that differences in health systems and the lesser prominence of cultural/linguistic barriers might result in inherently different barriers to HIV prevention and care. After review of titles and abstracts, 92 citations were selected for full article review. After reviewing full articles for inclusion criteria, 67 were excluded and 25 included in this review. We grouped articles into two distinct topics: 16 articles were used for survival/mortality, and 15 for delayed diagnosis. Six articles had overlapping data on both topics.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow diagram

Data Collection and Data Measures

Data were compiled into Microsoft Excel tables. The following data were extracted: study authors, year of publication, study location, years and duration of study, study population or cohort, number of study participants including percent male and percent Hispanic, median age of study participants, CD4 count at entry, % AIDS at entry, HIV transmission risk, outcome measure, and outcome result.

The definition of late diagnosis or delayed presentation to care varied from by study. We broadly defined late presentation as any article that measured concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis, time to AIDS, CD4 count on initial presentation, opportunistic infection at HIV diagnosis, and non-early diagnosis of HIV.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Populations

Although the Hispanic population in the US is highly heterogeneous, the majority of studies analyzed all Hispanics as one group, ignoring differences in country of origin, foreign versus US birth, English proficiency, and gender. Of the 15 articles reviewed for delayed HIV diagnosis or enrollment in care [9-23], two included only men (one of them only MSM) [15, 21], one included only heterosexually-acquired HIV [11], and five specifically evaluated foreign-born Hispanics (Tables 1, 2) [12, 13, 18, 19, 22]. Of the 16 articles (Tables 3, 4) evaluated for survival data [11-15, 17, 24-33], one included only women [24] and two included only men (one of them only MSM) [15, 21]. Only two survival articles evaluated differences between US-born and foreign-born Hispanics [13, 26]. In total, only six articles presented data on place of birth [12, 13, 18, 19, 22, 26]; of these, only two performed analysis by specific countries of origin [13, 26], and one presented data on language preference [22].

Table 1.

Delayed HIV diagnosis

| First Author, Pub.Year (Ref. No.) |

Source of Data, Location, Year |

Study population | N, %male, %Hispanic |

Age (median, years) |

Outcome of Interest |

Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hall 2006 (17) |

1996-2001 CDC surveillance data from 25 states |

≥13 years-old diagnosed with HIV between 1996-2001. Followed through December 31, 2002 |

N=98,885 M:73% H: 7.9% |

39% were between 30-39 |

Proportion with AIDS within l year of HIV diagnosis |

Late HIV diagnosis* (Percentage) |

|||

| White | 40.6% (40.3-41.0) | ||||||||

| Black | 39.4%(39.0-39.7) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 46.7% (46.2-47.3) | ||||||||

| * adjusted for age, sex, transmission category and year of diagnosis | |||||||||

| Hall 2007 (15) |

1996-2002 CDC surveillance data from 33 states |

MSM <13 vears- old with HIV diagnosis between 1996- 2002 |

43,994 M:100% H: 14.1% |

- | Proportion with AIDS within 1 year of HIV diagnosis |

Late HIV diagnosis* (Percentage) |

|||

| White | 18.4% (17.9-18.9) | ||||||||

| Black | 23.1% (22.4-23.7) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 23.7% (22.6-24.7) | ||||||||

| * adjusted for age and diagnosis year. | |||||||||

| Torrone 2007 (21) |

2000-2004, North Carolina Partner Counseling and Referral Services (PCRS) surveillance database records |

Men between 18 and 30 years old diagnosed with HIV between January 1, 2000, and December, 31, 2004 |

n=1117 M:100% H:ll% |

100% between 18-30 |

Late diagnosis defined as AIDS diagnosis at first documented HIV test |

Late HIV diagnosis (Percentage) |

AOR* | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 11.5% | Ref. | |||||||

| Hispanic | 29.2% | 2.23 (1.37-3.65) | |||||||

| * Adjusted for urban residency, college enrollment, prior incarceration, history of IDU, use of internet to meet sexual partners, syphilis co-infection, partner with known HIV, sexual risk, age. | |||||||||

| Esplnoza 2007 (11) |

1999-2004 CDC surveillance data from 29 states |

Heterosexuallv- acauired HIV in ≥13 year-olds with HIV diagnosis between 1999- 2004 |

n=52,569 M:26% H: 10% |

33% were between 30-39 |

Proportion with concurrent HIV and AIDS diagnosis |

Proportion concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis | |||

| White | 23% | ||||||||

| Black | 20% | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 23% | p=<0.001 | |||||||

| AOR of concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis among Hispanics* | |||||||||

| Female | Ref | ||||||||

| Male | 1.58 (1.39,1.80) | ||||||||

| *adjusted for age and year of diagnosis | |||||||||

| Espinoza 2008(13) |

2005 CDC surveillance data from 33 states |

≥13 year-old Hispanics with HIV diagnosis in 2005 |

N=7,561 M:77% H: 100% Place of birth U.S.: 29% Foreign: 54% Unknown: 17% |

42% were between 30-39 |

Proportion with AIDS within 1 year of HIV diagnosis |

Late HIV diagnosis by place of birth (Percentage) |

AOR for Late Diagnosis* | ||

| U.S. born | 39.1 | Ref. | |||||||

| Puerto Rico | 39.5 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | |||||||

| Mexico | 55.2 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.5) | |||||||

| Central America | 58.5 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.2) | |||||||

| *adjusted for sex, age group, place of birth, and transmission category. | |||||||||

| Espinoza 2009 (12) |

2003-2005 CDC surveillance data from 48 US border counties in 4 states (CA, NM, TX,AZ) |

≥13 year with HIV diagnosis between 2003- 2005 |

N=3090 M:N/A H:46% |

33% were between 30-39 |

Proportion with AIDS within 1 year of HIV diagnosis |

Late HIV diagnosis (Percentage) |

AOR for late diagnosis* | ||

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| White | 37% | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Black | 37% | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 1.3 (0.7- 2.5) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 46% | 1.4(1.2-1.7) | 2.2(1.2-3.8) | ||||||

| U.S. born | 39% | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Foreign-born | 51% | 1.7 (1.4-2.2) | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | ||||||

| *adjusted for sex, age group, place of birth, race/ethnicity, and transmission category | |||||||||

| Hall 2009 (16) |

2001-2005 CDC surveillance data from 33 states |

≥13 years old with HIV diagnosis between 2003- 2005 |

N=126,382 M:72% H: 18.2% |

- | Proportion with AIDS within 1 year of HIV diagnosis |

Late HIV Diagnosis (Percentage) |

|||

| White | 54.1% | ||||||||

| Black | 53.1% | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 57.7% | ||||||||

| Yang 2010 (23) |

2000-2008, Houston/Harris County, Texas, reported to Houston Department of Health and Human Services |

≥13 years old resident of Houston/Harris County, diagnosed with AIDS between 2000-2007 |

N=9964 M:78% H:21% |

35% were between 30-39 |

Proportion with late HIV diagnosis, defined as AIDS diagnosis within three months of initial HIV diagnosis) |

Unadjusted OR | AOR for late diagnosis* | ||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| Black | 0.99 (0.88-1.10) | 1.19 (1.04-1.34) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 1.64 (1.44-1.85) | 1.86 (1.61-2.16) | |||||||

| *adjusted for sex, race, mode of transmission, age group, country of origin, and private versus public sector care | |||||||||

AOR adjusted odds ratio, CDC centers for disease control and prevention, H Hispanic, M male, MSM men who have sex with men, N/A not available, OR odds ratio, Pub publication, Ref reference

Color scheme grey-Hispanics with worse outcome

Table 2.

Delayed enrollment in HIV care

| First Author, Pub. Year (Ref. No.) |

Source of Data, Location, Year |

Study population | N, %male, %Hispanic |

Age (median, years) |

Outcome of Interest |

Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levy 2007 (19) |

2000-2002 Northern California Public AIDS Program clinical database and county surveillance, San Mateo County |

All patients entering in San Mateo County AIDS program between Jan 2000-Mar 2002 |

N=391 M:74% H:24% |

US-born 35 (IQR 29-41) Immigrants 31 (IQR 27- 38) |

Prevalence of Opportunistic Infections (01) at entry into AIDS program (comparing U.S. born vs. foreign- born ) |

01 at presentation (Percentage) |

AOR* | ||

| U.S. born (7% Hispanic) | 17.2% | Ref. | |||||||

| Immigrants (79% Hispanic) | 29.8% (p= 0.009) |

2.98 (1.21-7.38) | |||||||

| AOR for 01 at diagnosis among Hispanics * | |||||||||

| U.S. born | Ref. | ||||||||

| Immigrant | 6.33 (0.58-69.68) | ||||||||

| *adjusted for monolingual status, Hispanic ethnicity | |||||||||

| Kelley 2007 (18) |

2000-2002 Grady Infectious Disease Program in Atlanta, GA |

Foreisn-born Mispanics from Spanish-speaking Latin American countries enrolled in care at Grady Infectious Disease Program |

N=75 M:72% H:100% |

38.5 | Proportion with AIDS at entry into care |

Proportion with AIDS at presentation: | |||

| Males | 57.7% | ||||||||

| Females | 10.0% | ||||||||

| Median CD4 | AOR for AIDS at diagnosis | ||||||||

| Hispanic Females | 224.5 | Ref. | |||||||

| Hispanic Males | 55 p=0.004 |

8.6 (1.3-58.7) | |||||||

| Schwarcz 2007 (20) |

1997-2001, 39 sites in 10 US cities |

Patients with HIV diagnosed in past y12 months, enrolled consecutively from the 39 sites, ≥18yo, never been on ARV |

n=964 M:75% H:21% |

41.5% were between ages 25-34 |

Prevalence of HIV diagnosis within 6 months of infection |

Early HIV diagnosis | AOR* | ||

| White | 29.3% | Ref. | |||||||

| Black | 15.5% | 0.52 (0.3-0.8) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 15.5% | 0.50 (0.3-0.8) | |||||||

| * adjusted for gender, age, risk behavior, history of STI, clinic type, and city | |||||||||

| Carabin 2008 (10) |

2002-2004 Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) Sites located along the U.S.-Mexico border |

HIV-positive patients receiving care at one of the SPNS sites in Harlingen and El Paso, Texas; Las Cruces, New Mexico; San Ysidro, California; and Tucson, Arizona |

N=707 M:82% H: 62% |

44% were between 30-39 |

AIDS or 01 at entry into care |

Median CD4 at presentation | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 376 (IQR 9-1188) | ||||||||

| Hispanics | 246 (IQR 4-1549) | p< 0.005 | |||||||

| Risk of 01 or AIDS at presentation of Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics by site | |||||||||

| Site | OR 01 at presentation | OR AIDS at presentation | |||||||

| A | 1.39 (0.57-3.29) | 1.85 (0.89-4.17) | |||||||

| B | 1.92 (1.03-3.80) | 2.03 (1.14-3.53) | |||||||

| C | 0.91 (0.49-1.83) | 1.19 (0.72-2.00) | |||||||

| D | 1.48 (0.58-3.75) | 0.93 (0.36-2.07) | |||||||

| E | 1.99 (1.04-4.18) | 1.92 (1.06-3.58) | |||||||

| Wohl 2009 (22) |

2000-2004 Los Angeles County |

≥18 years-old, Latino, diagnosed with AIDS and reported to Los Angeles County |

N=383 M:83 H:100% Foreign-born: 80% |

46% were between ages 30-39 |

Late tester defined as receiving AIDS diagnosis within 12 months of HIV diagnosis |

Odds ratio of Late HIV testing | |||

| Gender | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR* | |||||||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| Female | 0.9(0.5-1.5) | -- | |||||||

| Place of birth | |||||||||

| US-born | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| Foreign-born | 2.4 (1.4-4.0) | 0.9 (0.4-2.0) | |||||||

| Language of Interview | |||||||||

| English | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| Spanish | 3.0 (1.9-4.8) | 2.9 (1.4-6.0) | |||||||

| *adjusted for age, place of birth, education level, language of interview, and history of injection drug use | |||||||||

| Althoff 2010 (9) |

1997-2007 North American Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA- ACCORD) |

HIV-infected adults, > 18 yo, who first presented for clinical care between Jan 1997-Dec 2007 to 13 clinical cohorts in 17 U.S. states, Washington, D.C., and 3 Canadian provinces |

N=44,491 M:81% H:14% |

41 (IQR 34- 48) |

First measured CD4 count |

Observed mean CD4 + SD | Estimated change in CD4 (95% CI) | ||

| 1997 | 2007 | ||||||||

| White | 328±271 | 382±280 | 6 (5-7) | ||||||

| Black | 305±261 | 328±279 | 5 (3-7) | ||||||

| Latino | 293±246 | 383±301 | 9 (7-12) | ||||||

| *adjusted for age, sex, HIV transmission risk group, and cohort | |||||||||

| Giordano 2010(14) |

1999-2002, Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS (CPCRA) FIRST trial, 18 clinical trial units in the U.S. |

>13 years old, antiretroviral naive, randomly allocated to three ARV strategies: PI strategy (PI+NRTI); NNRTI strategy (NNRTI+NRTI); or three-class strategy (PI+NNRTI+NRTI) |

N=1397 M:79% H:17% |

Median age of Hispanics 36.7 years |

Time from HAART initiation to AIDS- defining event or death |

Unadjusted HR | Adjusted HR* | ||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| Black | 1.61 (1.14-2.27) | 1.36 (0.95-1.94) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 1.82 (1.20-2.76) | 1.48 (0.97-2.25) | |||||||

| *adjusted for age, gender, prior AIDS, injection drug use, hepatitis C coinfection, baseline CD4 cell count, HIV RNA level, and FIRST randomized strategy group | |||||||||

AOR adjusted odds ratio, ARV antiretroviral, CDC Centers for disease control and prevention, H Hispanic, HR hazard ratio, IQR interquartile range, M male, MSM men who have sex with men, N/A not available, NNRTI non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, OI opportunistic infection, OR odds ratio, PI protease inhibitor, Pub publication, Ref reference, STI sexually transmitted infection

Color scheme grey-Hispanics with worse outcome

Table 3.

Survival after AIDS diagnosis

| First Author, Publication Year (Reference No.) |

Source of Data, Location, Year |

Study population | N, %male, %Hispanic |

Age (median) | Follow-up period | Outcome of Interest |

Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nash 2005 (30) | 1993-2001 AIDS surveillance data reported to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene HIV/AIDS Reporting System (HARS) NYC Vital Statistics Registry |

≥13 year-old people living with AIDS (PLWA) in NYC, alive at any time during 1993- 2001 |

N=48,742 M: 71.3% H: 34.4% |

42% between 30- 39 years old |

Median follow up 3.7 years Followed until Dec. 31, 2001 |

HIV-related mortality rate AIDS diagnosis |

HIV-related death rate (per 1000 PLWA) |

Adjusted RR (2001)* | ||

| White | 18.5 | Ref | ||||||||

| Black | 34.4 | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 28.8 | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | ||||||||

| * adjusted for sex, age at AIDS diagnosis, transmission risk category, borough of residence, stage of disease at AIDS diagnosis, time since AIDS diagnosis, and first CD4 count | ||||||||||

| Sackoff 2006 (31) | 1999-2004 AIDS surveillance data reported to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene HIV/AIDS Reporting System (HARS) NYC Vital Statistics Registry |

≥ 13 years old PLWA, alive at any time between 1999 and 2004 |

N=68,669 M: 69.9% H: 33.4% |

46 years old | Followed until Dec. 31, 2004 |

HIV mortality rate from AIDS diagnosis |

HIV-related death rate (per 10,000 PLWA) |

Adjusted RR* | ||

| White | 183.3 (158.0-208.7) | Ref. | ||||||||

| Black | 369.1 (352.4-385.8) | 1.17 (1.09-1.25) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 289.5 (272.0-307.1) | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) | ||||||||

| *adjusted for age, sex, HIV transmission category, borough, residence in an area of poverty, year of AIDS diagnosis, and lowest CD4 lymphocyte count. | ||||||||||

| Hall 2006 (17) | 1996-2001, CDC surveillance data of AIDS diagnosis from 50 states |

≥13 years old. AIDS diagnosis from 1996-2001 |

N=262,744 M:76% H:20% |

42% were between 30-39 years old |

Followed until Dec. 31, 2002 |

3-year survival after AIDS diagnosis |

3-year survival (Percentage) |

RR of death at 3 years* | ||

| White | 82.3 (82.0-82.6) | Ref. | ||||||||

| Black | 77.2 (77.0-77.5) | 1.15 (1.12-1.18) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 79.0 (78.6-79.3) | 1.16 (1.13-1.20) | ||||||||

| *adjusted for sex, age, transmission category, CD4 count at diagnosis, diagnosis year, and population density of area at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Espinoza 2009 (12) | 1996-2004 CDC surveillance data from 48 US border counties in 4 states (CA, NM,TX,AZ) |

≥13 year with AIDS diagnosis between 1996-2004 |

N= 12,377 M: 88.5% Hi: 46.8% 19.7% foreign- born |

72% between 30- 49 years old |

Followed until June 2007 |

3-year survival after AIDS diagnosis |

3 year survival (Percentage) |

|||

| White | 84.0 (83.7-84.2) | |||||||||

| Black | 81.7 (81.7-81.8) | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 81.7 (81.4-82.0) | |||||||||

| *adjusted for sex, age group, place of birth, race/ethnicity, transmission group, year of diagnosis, and CD4 lymphocyte count at time of diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Espinoza 2008 (13) | 1996-2003 CDC surveillance data from U.S. 50 states, D.C., and 5- US-dependent areas |

AIDS diagnosis among Hispanics in adolescents and adults |

N=69,484 M: 77.5% H:100% |

70% were between 30-49 years old |

Followed until June 2007 |

Survival time after diagnosis of AIDS |

Survival 36 months after AIDS diagnosis | |||

| Place of birth | % (95% confidence interval) | |||||||||

| U.S. | 80.8 (80.6-81.0) | |||||||||

| Puerto Rico | 73.6 (73.4-73.8) | |||||||||

| Mexico | 81.6 (81.4-81.7) | |||||||||

| Central America | 83.4 (83.3-83.5) | |||||||||

| * adjusted for sex, age group, transmission category, and CD4 count at time of diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Woldemichael 2009 (33) |

1993-2001 surveillance data reported to the Chicago Department of Public Health |

≥ 13years old diagnosed with AIDS between Jan. 1993 and Dec. 2001 Only post-HAART data included here (1996-2001) |

N=5806 (post- HAART) M:78% H:15% |

74% between 30- 49 years old |

Until Dec 31, 2003 | 1,3 and 5 year survival estimates after AIDS diagnosis |

5-year survival (Proportion) |

Adjusted HR for HIV-related death* |

||

| White | 0.83 | Ref. | ||||||||

| Black | 0.73 | 1.51 (1.26-1.80) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.79 | 1.22 (0.97-1.53) | ||||||||

| * adjusted for gender, mode of transmission, age at diagnosis, and opportunistic diseases. | ||||||||||

| Arnold 2009 (25) | 1996-2006 AIDS surveillance data reported to the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) |

AIDS diagnosis between Jan 1, 1996 to Dec. 31, 2000, aged ≥15, and surviving at least 30 days from AIDS diagnosis |

N=3866 M: 89.9% H: 14.6% |

55% between 29- 59 years old |

Until Dec. 31,2006 | Time from AIDS diagnosis to AIDS death and all- cause mortality |

5 year all cause mortality HR* | |||

| Model 1 | Full Model | |||||||||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

| Black | 1.24 (1.02-1.51) | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.82 (0.64-1.06) | 0.77 (0.59-1.00) | ||||||||

| * Model 1 adjusted for transmission risk. Full model adjusted for transmission risk, neighborhood socioeconomic context, age at diagnosis, insurance status, and ARV initiation | ||||||||||

| Hall 2007 (15) | 1994-2004, CDC surveillance data from 25 states |

MSM≥13 years old with AIDS diagnosis between 1996-2002 |

N= 62,045 M:100% H:16% |

47% between 30- 39 years old |

Followed until 2004 |

3-year survival after AIDS diagnosis |

3 year survival* (Percentage) |

|||

| White | 84.5 (84.2-84.8) | |||||||||

| Black | 80.6 (80.2-81.0) | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 85.2 (84.9-85.4) | |||||||||

| *adjusted for age, diagnosis year, and baseline CD4 | ||||||||||

| Espinoza 2007 (11) | 1996-2003, CDC surveillance data from 50 U.S. states |

Heterosexuallv- acauired. > 13 years old with AIDS diagnosis between 1996-2003 |

N=86923 M:44% H:NR |

35% were between 30-39 years old |

Followed until June 2005 |

1,2,3, and 4 year survival estimates |

Adjusted 4-year survival probability* | |||

| Male | Female | |||||||||

| White | 0.82(0.81-0.82) | White | 0.81(0.81-0.81) | |||||||

| Black | 0.79(0.77-0.80) | Black | 0.76(0.76-0.77) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 0.85(0.85-0.86) | Hispanic | 0.84(0.84-0.85) | |||||||

| * adjusted for gender, age group, year of diagnosis, and CD4 lymphocyte count at diagnosis (excluding deaths within 1 month of AIDS diagnosis) | ||||||||||

| Hanna 2008 (26) | 2002-2005 AIDS surveillance data reported to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene HIV/AIDS Reporting System (HARS) NYC Vital Statistics Registry |

≥13 years old with AIDS diagnosis between January 1,2002 and June 30,2005 |

N=15,211 M:6796 H:32% |

41 years old (IQR 35-48) |

Followed until Dec 31,2005 |

Time from AIDS diagnosis to HIV- related death |

Adjusted HRfor HIV-related death* | |||

| White | Ref | |||||||||

| Black | 1.18 (0.99-1.39) | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.69 (0.56-0.84) | |||||||||

| Country of Origin: | ||||||||||

| U.S. Born | Ref. | |||||||||

| Puerto Rico | 2.53 (2.04-3.15) | |||||||||

| Caribbean | 1.74 (1.47-2.05) | |||||||||

| Central and South America | 1.65 (1.29-2.12) | |||||||||

| *adjusted for gender, age, concurrent AIDS diagnosis, country of birth, transmission category, borough, poverty, CD4 lymphocyte count at AIDS diagnosis, and year of AIDS diagnosis. | ||||||||||

AOR adjusted odds ratio, CDC centers for disease control and prevention, H Hispanic, HAART highly active antiretroviral therapy, HR hazards ratio, M male, MSM men who have sex with men, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, PUNA persons living with AIDS, Ref reference, RR relative risk

Color scheme grey-Hispanics with worse outcome

Table 4.

Survival after HIV diagnosis or enrollment in care

| First Author, Publication Year (Reference No.) |

Source of Data, Location, Year |

Study population | N, %male, %Hispanic |

Age (median) | Follow-up period | Percentage with AIDS |

Outcome of Interest |

Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGinnis 2003 (29) |

1999-2001, National administrative inpatient and outpatient data from the VA Healthcare Systems |

Veterans 25-84 years old diagnosed with HIV between Junel999-Sept 2001 |

N=5676 M:97% H:9% |

49 years old | Followed until Sep. 2002 |

Whites 24.3% Blacks 27.7% Hispanics 41.4% |

Survival from HIV diagnosis to death |

Age-adjusted HR | ||||

| White | Ref | |||||||||||

| Black | 1.41 (1.19-1.66) | |||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.41 (1.06-1.86) | |||||||||||

| *adjusted for age | ||||||||||||

| Harrison 2010 (27) | 1996-2005 CDC surveillance data from 25 states |

≥ 13 years old diagnosed with HIV between 1996- 2005 |

N=220,646 M:74% H:9% |

NR | Followed until Dec. 31, 2007 |

33%* *Note that 42% were missing CD4 count within 6 months of diagnosis |

Estimated Life Expectancy (ELE) and Average Years of Life Lost (AYLL)* *AYLL calculated by subtracting the estimated life expectancy after HIV diagnosis from the life expectancy in general population (matched by age, sex, race, and calendar year) |

2005 ELE | ||||

| Male | Female | |||||||||||

| White | 25.5 (24.9-26.1) | 21.4 (20.8-22.0) | ||||||||||

| Black | 19.9 (19.6-20.2) | 24.2 (23.3-25.1) | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 22.6 (21.9-23.3) | 21.2 (19.8-22.7) | ||||||||||

| 2005 AYLL | ||||||||||||

| 20 y.o | 40 y.o | 60 y.o. | ||||||||||

| White | 24.4 | 16.9 | 9.3 | |||||||||

| Black | 26.4 | 18.1 | 10.1 | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 30.2 | 23.3 | 15.3 | |||||||||

| Hall 2006 (17) | 1996-2001 CDC surveillance data of HIV diagnosis from 25 states |

≥13 years old diagnosed with HIV from 1996- 2001 |

N=98,003 Male: 73% Hispanic: 8% |

39% were between 30-39 years old |

Followed until Dec. 31, 2002 |

41%* *Note that 55% were missing CD4 count |

3-year survival after HIV diagnosis |

3-year survival (Percentage) |

RR of death at 3 years* | |||

| White | 90.7% (90.4-91.1) | Ref. | ||||||||||

| Black | 89.5% (89.2-89.8) | 1.17 (1.12-1.23) | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 90.3% (89.6-91.0) | 1.06 (0.98-1.16) | ||||||||||

| *adjusted for age, transmission category, CD4 count at diagnosis, AIDS at HIV diagnosis, diagnosis year, population density of area of residence | ||||||||||||

| Losina 2009 (28) | HIV research network (HIVRN) (Patients enrolled in HIV care) |

HIV-infected patients enrolled at one of the 7 HIVRN sites (6 academic and 1 community) |

N=8091 M:75% H: 20.6% |

33 +/− 7.5 years old (mean) |

N/A | Overall: 42.1% White: 36.4 Black: 44.2 Hispanic: 45.5 |

Estimated Life Expectancy from age 33 Years of Life Lost: calculated by subtracting estimated life in patients in HIVRN cohort from demographically- adjusted life expectancy if patients received HAART according to guidelines |

Risk adjusted life expectancy (years)* |

Years of Life Lost** | |||

| White | 22.2 | 3.2 | ||||||||||

| Black | 17.5 | 3.0 | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 20.2 | 3.9 | ||||||||||

| *adjusted for the following risks: MSM, IDU, multiple sex partners, being a CSW, and history of STI | ||||||||||||

| **attributed to late initiation or early discontinuation | ||||||||||||

| AnastOS 2005 (24) | 1993-2005, Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) cohort Bronx, Brooklyn, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago |

HIV-positive women initiating HAART |

N=961 M:0% H: 21.296 |

H: 37 years old [IQR 32.6,41.8] |

Median: 5.1 years | AIDS prior to ARV treatment: White 43.5% Black 47.5% Hispanic 47.5% |

Time from HAART initiation to death |

All cause mortality* | AIDS-related mortality* | |||

| RH | p-value | RH | p-value | |||||||||

| Black | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||||

| White | 0.71 | 0.124 | 0.56 | 0.127 | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.81 | 0.307 | 1.01 | 0.985 | ||||||||

| * adjusted for ARV use, age, AIDS-defining illness, nadir CD4, peak HIV viral load, HIV exposure category. | ||||||||||||

| Silverberg 2009 (32) |

1996-2005, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC) California death certificates and Social Security Administration data sets. |

HIV-positive individuals initiatine HAART at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between 1996-2005 |

N=4686 H: 14% (Among Hispanic, 90.5% were male) |

White 42 years old (IQR 36,49) Black 41 years old (IQR 35,48) Hispanic 37 years old (IQR 33,44) |

Median years f/u (IQR): White 4.7 (1.7-8.0) Black 3.4 (1.4-6.6) Hispanic 3.5 (1.4- 6.6) |

AIDS prior to ARV initiation: White 58.0% Black 59.6% Hispanic 58.3% |

Time from ARV initiation to all- cause mortality |

All cause mortality* HR |

||||

| White | Ref | |||||||||||

| Black | 1.17 (0.8-1.7) | |||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.90 (0.6-1.4) | |||||||||||

| *adjusted for age, gender, year of ARV initiation, prior ARV, socioeconomic status, depression, Charlson Score, MSM status. | ||||||||||||

| Giordano 2010 (14) |

1999-2002, Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS (CPCRA) FIRST trial, 18 clinical trial units in the U.S. |

≥13 years old. antiretroviral naive, randomly allocated to three ARV strategies: PI strategy (PI+NRTI); NNRTI strategy (NNRTI+NRTI);or 3-class strategy (PI+NNRTI+NRTI) |

N=1397 M:79% H:17% |

Median age of Hispanics 36.7 years |

Median follow-up 5 years |

Prior AIDS White 30.2% Black 41.1% Hispanic 40.8% |

Time from HAART initiation to death |

Unadjusted HR | Adjusted HR* | |||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||||||||||

| Black | 1.56 (1.09-2.24) | 1.38 (0.94-2.01) | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.09 (0.66-1.79) | 1.05 (0.64-1.74) | ||||||||||

| *adjusted for age, gender, prior AIDS, injection drug use, hepatitis C coinfection, baseline CD4 cell count, HIV RNA level, and FIRST randomized strategy group | ||||||||||||

AOR adjusted odds ratio, ARV antiretroviral, CDC centers tor disease control and prevention, CSW commercial sex worker, H Hispanic, HAART highly active antiretroviral therapy, HR hazards ratio, IDU injection drug use, IQR interquartile range, M male, MSM men who have sex with men, N/A not applicable, NNRTI non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor NR not reported, OR odds ratio, PI protease inhibitor, PUNA persons living with AIDS, Ref reference, RR relative risk, STI sexually transmitted infection

Color scheme grey-Hispanics with worse outcome

Outcomes

Delayed HIV Diagnosis

Eight studies (Table 1) reported stage of HIV at time of diagnosis based primarily on HIV cases reported to the CDC (n = 6) or other public health surveillance records (n = 2) [11-13, 15-17, 21, 23]. Definition of late HIV diagnosis varied by study, ranging from concurrent diagnosis of HIV/AIDS to proportion with AIDS within 1 year of HIV diagnosis. Despite these differences, in all but one of these studies, Hispanics had a delayed HIV diagnosis compared to Whites. CDC data from 1996 to 2001 showed that within 1 year of HIV diagnosis, 46.7% of Hispanics were diagnosed with AIDS compared to 40.6% of Whites and 39.4% of Blacks [17]. More recent CDC data (2001–2005) found a worsening in this trend for all ethnic/racial groups, with over half of all Hispanics diagnosed late with HIV infection (57.7%) compared to 53.1% of Black and 54.1% of Whites [16]. Although late presentation was less common among men who have sex with men (MSM) of all racial/ethnic backgrounds, Hispanic MSM were diagnosed later than White MSM (24% vs. 18% late presentation, respectively). The only study reporting similar timing of diagnosis between Hispanics and Whites restricted the analysis only to individuals with heterosexually-acquired HIV [11].

Among Hispanics, being foreign-born or male increased the risk for delayed diagnosis [11-13]. According to 2005 CDC data, approximately 40% of Hispanics born in the US had a delayed diagnosis compared to 55% of Mexicans and 59% of Central Americans (AOR for late diagnosis 2.2 and 2.5, respectively) [13]. Along the US-Mexico border, 46% of all Hispanics are diagnosed late compared to 37% of Whites, with a higher proportion of late diagnoses among foreign-born compared to US-born individuals (51% vs. 39%) [12]. In this study, there was an increased risk of delayed diagnosis among foreign-born males (AOR 1.7, 95% CI 1.4–2.2) compared to US-born males, but not between foreign-born and US-born females [12]. The CDC data on heterosexually-acquired HIV infection also found that Hispanic males had a 1.6 (95% CI 1.4–1.8) increased odds of concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis compared to Hispanic females [11].

Delayed Enrollment in HIV Care

Seven studies (Table 2) reported stage of HIV by race/ethnicity at enrollment in HIV clinical care [9, 10, 14, 18-20]. All studies showed that Hispanics or immigrants present to clinical care at a later stage in their HIV disease, as measured by percent with AIDS or opportunistic infections (OIs), lower CD4 cell count, or faster progression to AIDS or death. According to data from a ten-city study in the US, Whites were twice as likely as Hispanics and Blacks to be diagnosed very early (within 6 months of infection) [20]. In a national clinical trial study for anti-retroviral naïve patients, Hispanics were more likely to progress to AIDS or death in unadjusted analysis, although this association disappeared after adjustment for baseline CD4 count and prior AIDS diagnosis [14]. Along the US-Mexico border, Hispanics were more likely to present to care with AIDS or OIs at two of six public health HIV clinics, and the mean CD4 count at presentation was lower among Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics at all sites (256 cell/m3 vs. 376 cells/m3) [10]. Data from the North American Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) cohort found that while Hispanics presented with a lower mean CD4 count in 1997 (Hispanics 293 cells/mm3, White 328 cells/mm3, Blacks 305 cells/mm3), this disparity lessened over time, and Hispanics had the greatest improvement in estimated CD4 count at presentation from 1997 to 2007 [9].

Three studies evaluated the difference between foreign-born and US-born individuals. In Northern California Public AIDS Program, Hispanics were not at greater risk of late presentation when compared to non-Hispanics, but immigrants (79% Hispanic) were almost three times more likely to have an OI at HIV diagnosis than non-immigrants (7% Hispanic) [19]. In Georgia, foreign-born Hispanic males were at particularly high risk for late presentation to care [18], but among Hispanics in Los Angeles (LA) County, on adjusted analysis, there was no difference by place of birth or gender in adjusted analysis [22]. However, Spanish-speaking Hispanics in LA County were almost three times more likely to present late compared to English-speaking Hispanics [22].

Survival/Mortality

Sixteen studies reported survival or mortality rates for HIV-infected Hispanic individuals (Tables 3, 4) [11-15, 17, 24-33]. Of these, ten reported survival specifically in patients diagnosed with AIDS [11-13, 15, 17, 25, 26, 30, 31, 33], three reported survival after HIV diagnosis [17, 27, 29], and four reported survival after engagement in HIV care or treatment with ARVs [14, 24, 28, 32].

Survival after AIDS Diagnosis

Survival among Hispanic patients diagnosed with AIDS was worse in four studies (Table 3) [12, 17, 30, 31]. In the two studies of AIDS surveillance data from New York City, the earlier study (1993–2001) showed a 20% increased risk of death among Hispanics compared to Whites (95% CI 10–40%) [30]. The later study (1999–2004) found that although Hispanics had a higher HIV-related death rate of 290 per 10,000 people living with AIDS (PLWA) compared to Whites (183 per 10,000 PLWA), after adjustment for age, sex, HIV transmission category, NYC borough, poverty, year of AIDS diagnosis, and CD4 cell nadir, there was no significant difference in relative risk of death [30, 31]. CDC data from 1996 to 2001 demonstrate a 16% increased risk of death for Hispanics compared to Whites three years after AIDS diagnosis, even after controlling for similar confounding factors [17]. In an analysis of three-year survival rates after AIDS diagnosis among four US-Mexico Border States (1996–2004), Hispanics were also found to have decreased survival compared to Whites [12].

Three articles reported better survival in specific risk-categories: Hispanic MSM diagnosed with AIDS between 1996 and 2002 had a slightly higher three-year survival than White MSM (85.2 vs. 84.5%) [15]; Hispanics with heterosexually acquired HIV and an AIDS diagnosis between 1996 and 2002 also had a higher four-year survival probability than Whites (85 vs. 82% for males, and 84 vs. 81% for females) [11]. Hispanics diagnosed with AIDS in New York City between 2002 and 2005, had better survival among all Hispanics compared to Whites (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.69, 95% CI 0.56–0.84) [26]. Two studies of AIDS-reported data from specific cities (Chicago and San Francisco) found no difference in survival, or non-statistically significant trends towards lower survival [25, 33].

Only two studies reported differences among Hispanics according to country of origin. Although overall survival was similar among Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics diagnosed with AIDS in New York City (2002–2005), the prognosis was worse for foreign-born Hispanics compared to US-born individuals [26]. Individuals born in Puerto Rico had more than twice the risk of HIV-related death (HR 2.53) than US-born individuals, while those born in the Caribbean and Central America had more than a 50% higher risk of death (HR 1.74 and 1.65, respectively) [26]. A study evaluating CDC data of Hispanics diagnosed with AIDS between 1996 and 2003 found disparities in three-year survival by place of birth, with worse survival among those born in Puerto Rico, better survival among US-born Hispanics, and the best survival among those born in Central America [13].

Survival after HIV Diagnosis, Enrollment in HIV Care, or HAART Initiation

Seven studies (Table 4) reported survival in Hispanics: after HIV diagnosis (n = 3) [17, 27, 29], enrollment in HIV care (n = 1) [28], or ART initiation (n = 3) [14, 24, 32]. Data from the Veteran’s Administration Systems of all reported HIV cases diagnosed in veterans between 1999 and 2001 showed that Hispanics and Blacks had a 41% (95% CI 6–86%) increased risk of death compared to Whites [29]. In addition, Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to have first been identified as HIV-infected during an inpatient visit (20 and 16% versus 11% for Whites, respectively), and a greater proportion of Hispanics had AIDS (41 versus 24–28% for non-Hispanics) [29]. Hispanics with an HIV diagnosis reported to the CDC had a similar three-year survival compared to Whites [17], but the overall life expectancy was lower in Hispanic males than White males [27, 28]. Hispanics had a significantly higher average years of life lost (AYLL) after HIV diagnosis than both Whites and Blacks at all age categories [27]. Similarly, data from the HIV research network (HIVRN) of patients enrolled in HIV care at seven sites showed a lower life expectancy after HIV diagnosis in Hispanics compared to Whites, and more years of life lost were attributed to late initiation or early discontinuation of ART among Hispanics than other racial and ethnic groups [28]. In contrast, all three studies evaluating survival after ART initiation found no difference in all cause mortality between Hispanic and White patients [14, 24, 32].

Discussion

We performed a systematic review evaluating timing of HIV diagnosis and survival after HIV/AIDS diagnosis for Hispanics in the US. Despite various definitions of delayed diagnosis, the majority of studies showed that Hispanics were more likely to be diagnosed later than Whites. This is particularly concerning in light of data from two large studies showing a survival benefit for patients initiating ART before the CD4 count declines to less than 500 cells/ll [34, 35], and recent changes in the DHHS guidelines recommending earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy [36]. Although there was a trend towards lower survival among Hispanics with HIV/AIDS compared to Whites, there were notable exceptions that highlight the heterogeneity of the Hispanic population in the US.

Almost all of the studies reviewed showed that Hispanics present later in the course of HIV disease compared to Whites, with males and foreign-born Hispanics at greatest risk for late diagnosis. Only one study, involving individuals with heterosexually-acquired HIV, showed no difference in late diagnosis between Whites and Hispanics [11]. It did, however, show later presentation among Hispanic men compared to Hispanic women [11]. Similarly, among foreign-born Hispanics presenting to a clinic in Atlanta, GA, men were 8.6 times more likely to present with AIDS than Hispanic women [18]. Earlier detection of HIV among Hispanic women may be related to opportunities for HIV screening at routine gynecology or prenatal visits [11]. In support of this hypothesis, the Atlanta study reported that that 25% of the women were diagnosed during prenatal visits [18]. Even though Hispanic women are less likely than Hispanic men to present late, Hispanic women are still more than twice as likely as White women to present late in the disease [12]. Therefore, HIV testing and prevention efforts need to be expanded to prevent late diagnosis among all Hispanics. A culturally acceptable method to increase testing among Hispanic women may involve expanding existing services offered at family planning and women’s health visits. Expanding testing among Hispanic males is more challenging, since many do not access the medical system until they are symptomatic with disease [37]. The expansion of culturally-appropriate street and community outreach education and testing may be necessary to reach Hispanic men.

Delayed diagnosis among foreign-born Hispanics is not surprising given well-documented barriers in access to care, particularly for individuals without health insurance and limited English proficiency [38-40]. Given the clear benefits associated with early initiation of ART, we expected that delayed diagnosis would decrease survival among Hispanics. However, the data on survival after HIV or AIDS diagnosis were less consistent than the data on late presentation.

Among 11 studies evaluating ethnic and racial differences in survival after HIV or AIDS diagnosis, six showed worse survival, three showed no difference in survival, and three showed better survival among Hispanics compared to Whites [11, 12, 15, 17, 25-27, 29-31, 33]. One study found that Hispanics had worse survival than Whites after AIDS diagnosis, but equivocal survival after HIV diagnosis [17]. Hispanics in two specific transmission risk categories (MSM and heterosexual) were reported to have better survival than Whites. An important caveat is that most studies adjusted risks and survival estimates for stage of HIV at diagnosis (CD4 count, AIDS diagnosis, or OI), thereby masking the impact of late diagnosis on survival. Other possible explanations for the discrepancy between late diagnosis and survival include inaccurate data collection, such as differential underreporting on death certificates, especially if a significant proportion of foreign-born Hispanics with HIV return to their country of origin, or misclassification of Hispanic ethnicity as White. Another explanation for the discrepancy between survival and late presentation/access to care is that once engaged in HIV care, Hispanics are receiving appropriate care. In fact, outcomes after initiation of ART were similar between Hispanics and Whites, suggesting adequate adherence to therapy among Hispanics engaged in care [14, 24, 32].

It is important to note, however, that 50% of the studies found worse survival after HIV/AIDS diagnosis among Hispanics, and that specific Hispanic subgroups appear to be at highest risk for poor outcomes. In particular, even though Puerto Rican-born Hispanics do not present late compared to US-born Hispanics, Puerto Rican-born Hispanics with AIDS have significantly lower survival than US-born Hispanics [13]. Puerto Ricans have the highest rates of HIV transmission through intravenous drug use, and data were adjusted for transmission category, but unknown factors such as adherence and co-morbidities associated with IDU can affect survival estimates. In addition, non-mainland Puerto Ricans may be primarily receiving HIV treatment in Puerto Rico, and differences in mortality may be secondary to system-level differences in the health care system in Puerto Rico compared to mainland US [13].

Although foreign-born Hispanics were at greater risk for late diagnosis of HIV/AIDS than US-born Hispanics [12, 13, 19, 22], this delay in diagnosis did not always translate into worse survival. National surveillance data showed better survival among Hispanics with AIDS born in Mexico and Central America compared to US-born Hispanics [13]. However, a higher risk of death in Central and South Americans compared to US born Hispanics was reported in a study from New York [26]. Although HIV care is available to uninsured patients through the Ryan White Act, other factors such as language barriers, lack of familiarity with the US healthcare system, stigma, or fear of deportation often affect access to care. Both the Espinoza and Hanna studies analyzed survival after AIDS diagnosis, thereby controlling for late presentation to care [13, 26]. The reason for the conflicting results is unclear, but the discrepancies highlight the importance of evaluating local populations and specifically defining Hispanic subgroups to properly evaluate high risk groups that may be underrepresented in data from the heterogeneous Hispanic population as a whole.

Our study has several limitations. Many of the studies evaluated CDC name-based surveillance data that do not include HIV data from some states with large Hispanic populations, such as California. In addition, surveillance data and vital statistics data are subject to racial/ethnic misclassification, which is particularly problematic for Hispanics [41, 42]. Analysis of HIV reported cases or HIV cases engaged in care does not provide information about HIV-related mortality in individuals who were never diagnosed with HIV. Given significant delays in diagnosis among Hispanics, it is possible that HIV-related mortality was underestimated or underreported. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the majority of the studies did not distinguish among Hispanic subgroups. Few studies reported key variables related to migration, such as country of origin, and none reported in-depth analysis of acculturation factors, although one did mention language of interview. Although systematic review of the data allowed us to discern some higher risk groups, such as Hispanic males, Puerto Ricans, and foreign-born Hispanics, the data were insufficient for a conclusive analysis.

Conclusion

In this systematic review of late presentation of HIV and survival/mortality rates, we found evidence that Hispanics tend to present late in the course of their HIV disease compared to non-Hispanic whites. In particular, Hispanic males and foreign-born Hispanics tend to be at increased risk of late presentation, and Puerto Ricans are at highest risk of mortality. We did find that after initiation of ART, there was no difference in survival between Hispanics and Whites, which suggests that disparities in HIV/AIDS survival may be attributed to differences in access to care and delayed diagnosis. These findings have important implications for HIV preventive strategies, such as “test and treat,” and for early initiation of ART according to DHHS guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Page was supported by a K23 career development award (K23HD056957) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Appendix 1

“Hispanic Americans”[MeSH Terms] OR “Hispanic Americans”[All Fields] OR “Hispanic”[All Fields] OR “Hispanics”[All Fields] OR “latina”[All Fields] OR “Latinas”[All Fields] OR “Hispanic”[All Fields] OR “Hispanics”[All Fields] OR “Hispanic American”[All Fields] OR “Mexican-American”[All Fields] OR “Mexican Americans”[MeSH Terms] OR “Mexican Americans”[All Fields] OR “Puerto Rican”[All Fields] OR “Puerto Ricans”[All Fields] OR “Spanish American”[All Fields] OR “Spanish Americans”[All Fields] OR “Cuban American”[All Fields] OR “Cuban Americans”[All Fields] OR “Spanish speaking”[All Fields].

AND

“Hiv”[MeSH Terms] OR “HIV”[All Fields] OR “Human Immunodeficiency Virus”[All Fields] OR “Human Immunodeficiency Viruses”[All Fields] OR “AIDS virus”[All Fields] OR “AIDS viruses”[All Fields] OR “HTLV-III”[All Fields] OR “Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type III”[All Fields] OR “Human T Lymphotropic Virus Type III”[All Fields] OR “Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type III”[All Fields] OR “Human T Cell Leukemia Virus Type III”[All Fields] OR “Human T-Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type III”[All Fields] OR “Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type III”[All Fields] OR “LAV-HTLV-III”[All Fields] OR “Lymphadenopathy-Associated Virus”[All Fields] OR “Lymphadenopathy Associated Virus”[All Fields] OR “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Virus”[All Fields] OR “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Virus”[All Fields] OR “Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome”[mesh] OR “immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome”[All Fields] OR “immune reconstitution”[All Fields] OR “immune restoration”[All Fields] OR “viral suppression”[All Fields] OR “viral load”[mesh] OR “viral load”[All Fields] OR “viral burden”[All Fields] OR “virus titer”[All Fields] OR “CD4 Lymphocyte Count”[mesh] OR “CD4 Lymphocyte Count”[All Fields] OR “CD4 Lymphocyte Counts”[All Fields] OR “CD4 Counts”[All Fields] OR “CD4 count”[All Fields] OR “CD4 cell count”[All Fields] OR “CD4 cell counts”[All Fields] OR “T4 lymphocyte count”[All Fields] OR “T4 lymphocyte counts”[All Fields] OR “CD4-Positive T-Lymphocytes”[mesh] OR “CD4-Positive T-Lymphocytes”[All Fields] OR “CD4 Positive T Lymphocytes”[All Fields] OR “CD4-Positive T-Lymphocyte”[All Fields] OR “T4 cell”[All Fields] OR “T4 cells”[All Fields] OR “T4 lymphocytes”[All Fields] OR “T4 lymphocyte”[All Fields] OR “CD4 positive lymphocyte”[All Fields] OR “CD4 positive lymphocytes”[All Fields].

AND

“treatment outcome”[mesh] OR “treatment outcome”[All Fields] OR “treatment failure”[mesh] OR “treatment failure”[All Fields] OR “treatment failures”[All Fields] OR “prognosis”[MeSH] OR “prognosis”[All Fields] OR “prognoses”[All Fields] OR “disease free survival”[mesh] OR “disease free survival”[All Fields] OR “medical futility”[mesh] OR “medical futility”[All Fields] OR “nomograms”[mesh] OR “nomograms”[All Fields] OR “mortality”[subheading] OR “mortality”[MeSH] OR “mortality”[All Fields] OR “mortalities”[All Fields] OR “cause of death”[mesh] OR “cause of death”[All Fields] OR “fatal outcome”[mesh] OR “fatal outcome”[All Fields] OR “fatal outcomes”[All Fields] OR “fatality rate”[All Fields] OR “fatality rates”[All Fields] OR “fatality”[All Fields] OR “fatalities”[All Fields] OR “death rate”[All Fields] OR “death rates”[All Fields] OR “death”[All Fields] OR “deaths”[All Fields] OR “survival rate”[mesh] OR “survival rate”[All Fields] OR “epidemiology”[Subheading] OR “epidemiology”[All Fields] OR “morbidity”[All Fields] OR “morbidity”[MeSH Terms] OR “morbidity”[All Fields] OR “morbidities”[All Fields] OR “survival”[All Fields] OR “Late presentation”[All Fields] OR “access to care”[All Fields] OR “health services accessibility”[mesh] OR “health services accessibility”[All Fields] OR “availability of health services”[All Fields] OR “health services availability”[All Fields] OR “accessibility of health services”[All Fields] OR “program accessibility”[All Fields] OR “risk perception”[All Fields] OR “perception of risk”[All Fields] OR “perception”[mesh] OR “delayed diagnosis”[mesh] OR “delayed diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “delayed diagnoses”[All Fields] OR “late diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “late diagnoses”[All Fields] OR “acculturation”[MeSH Terms] OR “acculturation”[All Fields] OR “cultural assimilation”[All Fields] OR “culturally sensitive”[All Fields] OR “cultural sensitivity”[All Fields] OR “stigma”[All Fields] OR “taboo”[mesh] OR “taboo”[All Fields] OR “taboos”[All Fields] OR “deportation”[All Fields] OR “pre-judice”[mesh] OR “prejudice”[All Fields] OR “prejudices”[All Fields] OR “racism”[All Fields] OR “social discrimination”[All Fields] OR “segregation”[All Fields] OR “unrecognized infection”[All Fields] OR “Patient Compliance”[Mesh] OR “patient compliance”[All Fields] OR “patient noncompliance”[All Fields] OR “patient non compliance”[All Fields] OR “patient adherence”[All Fields] OR “patient nonadherence”[All Fields] OR “patient non adherence”[All Fields] OR “patient cooperation”[All Fields] OR “Medication Adherence”[Mesh] OR “medication adherence”[All Fields] OR “medication non adherence”[All Fields] OR “medication nonadherence”[All Fields] OR “medication compliance”[All Fields] OR “medication non compliance”[All Fields] OR “medication noncompliance”[All Fields] OR “medication persistence”[All Fields].

Contributor Information

Nadine E. Chen, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, Yale University, 135 College St, Suite 323, New Haven, CT 06517, USA

Joel E. Gallant, Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Kathleen R. Page, Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

References

- 1.HIV/AIDS among Hispanics—United States, 2001-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007 Oct 12;56(40):1052–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estimated Lifetime Risk for Diagnosis of HIV Infection Among Hispanics/Latinos—37 States and Puerto Rico. 2007 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Oct 15;59(40):1297–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Census Bureau [Accessed 2 Nov 2008];Minority population tops 100 million. US Census Bureau News http://wwwcensusgov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb07-70html. Updated 17 May 2007.

- 4.Alvarez ME, Jakhmola P, Painter TM, Taillepierre JD, Romaguera RA, Herbst JH, et al. Summary of comments and recommendations from the CDC consultation on the HIV/AIDS Epidemic and prevention in the Hispanic/Latino community. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 Suppl):7–18. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stallworth JM, Andia JF, Burgess R, Alvarez ME, Collins C. Diffusion of effective behavioral interventions and Hispanic/Latino populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 Suppl):152–63. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Vital Statistics System. [Accessed 2 August 2010]. 2006. Deaths, percent of total deaths, and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 10-year age groups by Hispanic origin, race for non-Hispanic population, and sex: United States, 1999-2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK5_2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed 30 July 2010];HIV Surveillance Report. 2008 20 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ Published June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, Brooks JT, Hogg RS, Bosch RJ, et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(11):1512–20. doi: 10.1086/652650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carabin H, Keesee MS, Machado LJ, Brittingham T, Williams L, Sonleitner NK, et al. Estimation of the prevalence of AIDS, opportunistic infections, and standard of care among patients with HIV/AIDS receiving care along the U.S.-Mexico border through the Special Projects of National Significance: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(11):887–95. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Hardnett F, Selik RM, Ling Q, Lee LM. Characteristics of persons with heterosexually acquired HIV infection, United States 1999-2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):144–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Hu X. Increases in HIV diagnoses at the U.S.-Mexico border, 2003-2006. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 Suppl):19–33. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Selik RM, Hu X. Characteristics of HIV infection among Hispanics, United States 2003-2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):94–101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181820129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giordano TP, Bartsch G, Zhang Y, Tedaldi E, Absalon J, Mannheimer S, et al. Disparities in outcomes for African American and Latino subjects in the flexible initial retrovirus suppressive therapies (FIRST) trial. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(5):287–95. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall HI, Byers RH, Ling Q, Espinoza L. Racial/ethnic and age disparities in HIV prevalence and disease progression among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1060–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall HI, Geduld J, Boulos D, Rhodes P, An Q, Mastro TD, et al. Epidemiology of HIV in the United States and Canada: current status and ongoing challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999) 2009;51(Suppl 1):S13–20. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a2639e. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall HI, McDavid K, Ling Q, Sloggett A. Determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis, United States, 1996 to 2001. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(11):824–33. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley CF, Hernandez-Ramos I, Franco-Paredes C, del Rio C. Clinical, epidemiologic characteristics of foreign-born Latinos with HIV/AIDS at an urban HIV clinic. AIDS Reader. 2007;17(2):73–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy V, Prentiss D, Balmas G, Chen S, Israelski D, Katzenstein D, et al. Factors in the delayed HIV presentation of immigrants in Northern California: implications for voluntary counseling and testing programs. J Immigr Minor Health/Center for Minority Public Health. 2007;9(1):49–54. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarcz S, Weinstock H, Louie B, Kellogg T, Douglas J, Lalota M, et al. Characteristics of persons with recently acquired HIV infection: application of the serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion in 10 US cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(1):112–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000247228.30128.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torrone EA, Thomas JC, Leone PA, Hightow-Weidman LB. Late diagnosis of HIV in young men in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(11):846–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31809505f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wohl AR, Tejero J, Frye DM. Factors associated with late HIV testing for Latinos diagnosed with AIDS in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1203–10. doi: 10.1080/09540120902729957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang B, Chan SK, Mohammad N, Meyer JA, Risser J, Chronister KJ, et al. Late HIV diagnosis in Houston/Harris County, Texas, 2000-2007. AIDS Care. 2010;22(6):766–74. doi: 10.1080/09540120903431348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anastos K, Schneider MF, Gange SJ, Minkoff H, Greenblatt RM, Feldman J, et al. The association of race, sociodemographic, and behavioral characteristics with response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999) 2005;39(5):537–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold M, Hsu L, Pipkin S, McFarland W, Rutherford GW. Race, place and AIDS: the role of socioeconomic context on racial disparities in treatment and survival in San Francisco. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV, Sackoff JE. Concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis increases the risk of short-term HIV-related death among persons newly diagnosed with AIDS, 2002-2005. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(1):17–28. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison KM, Song R, Zhang X. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on National HIV surveillance data from 25 States, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):124–30. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b563e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Losina E, Schackman BR, Sadownik SN, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, Chiosi JJ, et al. Racial and sex disparities in life expectancy losses among HIV-infected persons in the United States: impact of risk behavior, late initiation, and early discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):1570–8. doi: 10.1086/644772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGinnis KA, Fine MJ, Sharma RK, Skanderson M, Wagner JH, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Understanding racial disparities in HIV using data from the veterans aging cohort 3-site study and VA administrative data. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1728–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nash D, Katyal M, Shah S. Trends in predictors of death due to HIV-related causes among persons living with AIDS in New York City: 1993-2001. J Urban Health. 2005;82(4):584–600. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Horberg MA. Race/ethnicity and risk of AIDS and death among HIV-infected patients with access to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1065–72. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1049-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woldemichael G, Christiansen D, Thomas S, Benbow N. Demographic characteristics and survival with AIDS: health disparities in Chicago, 1993-2001. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S118–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, Merriman B, Saag MS, Justice AC, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(18):1815–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, de Wolf F, Phillips AN, Harris R, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1352–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents . Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed 20 Oct 2010]. Dec 1, 2009. pp. 1–161. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livingston G, Minushkin S, Cohn D. A Joint Pew Hispanic Center and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Research Report. [Accessed 20 Oct 2010]. 2008. Hispanics and Health Care in the United States: access, information and knowledge. Available at http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/91.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ransford HE, Carrillo FR, Rivera Y. Health care-seeking among Latino immigrants: blocked access, use of traditional medicine, and the role of religion. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):862–78. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):2021–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith DP, Bradshaw BS. Rethinking the Hispanic paradox: death rates and life expectancy for US non-Hispanic White and Hispanic populations. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1686–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.035378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swallen KC, West DW, Stewart SL, Glaser SL, Horn-Ross PL. Predictors of misclassification of Hispanic ethnicity in a population-based cancer registry. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(3):200–6. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]