Abstract

We investigated the vascular transport of exogenously applied proteins and compared their delivery to various aerial parts of the plant with carboxy fluorescein dye. Alexafluor tagged bovine serum albumin (Alexa-BSA) moves at a low level to upper parts of the plant and unloads to the apoplast. Alexafluor tagged Histone H1 (Alexa-Histone) moves rapidly throughout the plant and is retained in the phloem and phloem parenchyma. Both Alexa-Histone and -BSA were exported from leaf veins class II and III but they unloaded completely into the leaf lamina with barely any residual fluorescence left inside the leaf veins. Fluorescein tagged hepatitis C virus core protein (fluorescein-HCV) moves more rapidly than BSA through the plant and was restricted to the leaf veins. Fluorescein-HCV failed to unload to the leaf lamina. These combined data suggest that there is not a single default pathway for the transfer of exogenous proteins through the plant. Specific protein properties appear to determine their destination and transport properties within the phloem.

Keywords: fluorescent proteins, Phloem transport, protein trafficking, vascular transport, virus transport

Introduction

The vasculature of higher plants is a long-distance communication network. This network provides interorgan transfer of nutrients and signaling molecules needed for plant development or environmental responses. Various small molecules, macromolecules, mRNA, small RNA and proteins produced in mature tissues move through the plant vasculature to young developing tissues and meristematic regions. The plant vasculature is composed of xylem and phloem. The xylem mainly carries water and micronutrients which can also circulate into the phloem. The phloem is mainly for the unidirectional transport of photo assimilates, proteins, nucleic acids, signaling molecules, and other micronutrients to various organs of the plant.1,2

Long-distance transport of mRNA and small RNA in the phloem has been intensively studied and is central to regulating gene expression at the at the whole plant level. Phloem mobile transcripts and small RNAs controlling cell fate, phytohormone responses, and metabolism have been reported to move via the phloem in plant grafting experiments. For example, Gibberellic Acid Insensitivity (GAI) is a negative regulator of GA signaling. GAI mRNAs are phloem mobile, traffic into meristems, and are connected to developmental regulation.3 Flowering locus T (FT) is expressed in the phloem. FT proteins and mRNA move into the meristems where they contribute to flower development.4 Other non-cell autonomous proteins (NCAPs) bind and translocate mRNAs through sieve tubes to apical tissues. siRNAs and miRNAs are also graft transmissible and contribute to gene regulation in young tissues.5,6 This is best seen in GFP-expressing plants where post transcriptional gene silencing has been activated in a mature leaf.7 Establishing PTGS in upper leaves correlates with homologous siRNAs accumulating in phloem sap.

There are over 1,500 proteins in the phloem translocation stream.2 Their significance and roles in whole plant signaling are not as well understood. There has been more research done to monitor the vascular transport and unloading of exogenous proteins, such as GFP or plant viral movement proteins, than endogenous proteins. Researchers distinguish between the phloem transport properties of endogenous and exogenous proteins. Essentially, endogenous proteins are likely transported to specific destinations, such as FT to meristems where they contribute to cell fate determination. Such a mechanism of transport is selective, since FT is specifically targeted to the meristem and not all phloem proteins unload there.4 Exogenous proteins follow the translocation stream and their unloading may depend on specific properties of the proteins. For example, GFP is not of plant origin and does not enter a selective pathway.8,9 GFP diffuses into phloem across plasmodesmata connecting companion cells (CC) and sieve elements (SE). GFP follows the phloem translocation stream and unloads in sink tissues by diffusion. The patterns of GFP and carboxyfluorescein (CF) dye diffusion driven transport are often compared. Carboxyfluorescein (CF) dye is a commonly used indicator of long distance phloem transport.10,11 Plant viral movement proteins are also exogenous proteins and are similar to NCAPs, because they carry RNA long distance through the phloem.12,13 Unlike GFP, plant viral movement proteins (MPs) engage with plasmodesmata and gate open these channels to move from cell-to-cell and then enter the CC-SE complex. While GFP diffuses across most cell layers, viral MPs are selectively excluded from certain tissues. For example, phloem limited viruses traffic from the CC-SE complex to phloem parenchyma and bundle sheath cells, but cannot enter the mesophyll layer.14,15 The bundle sheath provides a cellular boundary for protein export. Therefore exogenous proteins have properties that affect their ability to enter and exit the phloem.

In this study we decided to compare the phloem transport of three exogenous proteins applied to N. benthamiana petioles and roots. Prior work comparing the transport of carboxy fluorescein dye, green fluorescent protein (GFP) and plant viral movement proteins suggest that not all exogenous proteins have similar abilities to exit the translocation stream or share the same fate in sink tissues. We selected three very different commercially available proteins, bovine serum albumin, histone H1 (from calf thymus), and hepatitis virus C (HCV) core protein. The histone H1 was antigenically conserved with plant histones and could potentially perform as an endogenous protein with respect to translocation and unloading. The goal of this work was to learn if plants differentiate exogenously applied proteins with respect to transport and post phloem sorting.

Results

Measuring the transfer of fluorescence intensity from the loading site into upper leaves

Commercially available Alexafluor488-BSA, Alexafluor488-Histone H1 (0.3 mg/ml) (here called Alexa-BSA and Alexa–Histone) and CF dye (60 μg/ml) were applied to either the L1 petiole11 or roots of N. benthamiana plants. Importantly concentrations of dye and protein used produced similar absorbance values. Leaves are numbered L1 to L5 in their order of emergence above the soil, L1 is the mature source leaf that lies closest to the soil surface and L5 is the youngest sink leaf to emerge. In reports when CF dye is applied to the cut L1 petiole, the dye follows the same route as photo assimilates and unloads in sink leaves.11 On occasions CF dye enters the xylem.11

To record protein and dye transfer to the upper leaves of N. benthamiana plants, 0.5 mm sections were cut from the petioles of each upper leaf at 10, 30, 60, and 90 min. Digital images of the cross sections were recorded using epifluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1A and B). We measured he fluorescence intensity in the central vascular bundle using ImageJ software. The average (n = 4) fluorescence units (FU) per mm3 were plotted (Fig. 1C and D).

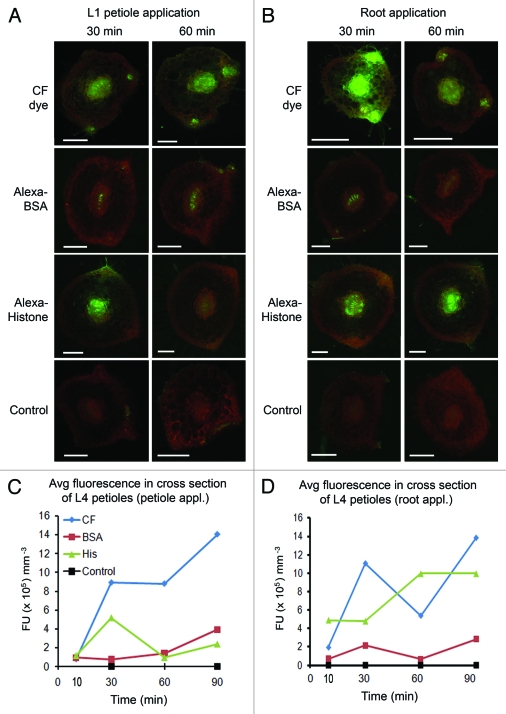

Figure 1.

Images of L 4 petiole cross sections of N. benthamiana. Images show the average fluorescence intensity of L4 petiole cross sections (n = 4) following L1 petiole (A) or root (B) application at 30 and 60 min. Plants were treated with CF dye, Alexa Fluor 488 BSA and Alexa Fluor 488 Histone H1. Bar = 500 μm. Two lateral veins along the adaxial side of the petiole were showed CF dye fluorescence.16,17 (C) and (D) graphically depict the average fluorescence values in the central vascular bundles of (n = 4) L4 petiole cross sections. CF dye reaches a maximum at 30 min, declines until 60 min. Uptake of Alexa-BSA is low when delivered to the roots. However, Alexa-Histone uptake is greater in the first 10 min following delivery to the roots than the L1 petiole. The amount of Alexa-Histone that transfers to L4 petioles reaches saturation and a plateau at 60 min.

Regardless of whether CF dye is applied to the L1 petiole or root, fluorescence occurs in the central vascular bundle and two lateral veins along the adaxial side.16,17 Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone were mostly absent from these lateral veins. We applied solutions containing CF dye, Alexa-BSA or Alexa-Histone to the L1 petiole, and 10 min later we observed fluorescence in the central vascular bundles of the upper leaf petioles. For the initial comparison we focused our attention on the L4 petioles (Fig. 1C) and at 30 and 90 min there were important differences among the three treatments (Fig. 1A). For CF dye, the fluorescence intensities in the central vascular bundle of L4 petioles reached a plateau at 30 min followed by a second increase in uptake between 60 and 90 min. Alexa-BSA treated plants showed lower levels fluorescence in the central vascular bundle which slowly improved over time. One explanation is that diffusion of Alexa-BSA in the phloem might be slow because it is a significantly larger molecule (66 kDa). Alexa-Histone produced greater fluorescence in cross sections (than Alexa-BSA) at 30 min but declined until 60 min (Fig. 1a). Alexa-Histone levels are roughly 50% of CF dye at 30 min (Fig. 1c).

CF dye, Alexa-BSA, and Alexa-Histone were applied to N. benthamiana roots and each show increased intensities during two time frames in the central vascular bundle. CF dye reaches a maximum at 30 min in the central vascular bundle. There is also significant fluorescence in surrounding nonvascular tissues (Fig. 1B and D). As with petiole application, fluorescence declines in cross sections until 60 min and then increases between 60 and 90 min (Fig. 1D). One explanation is that the CF dye leaks into surrounding tissues and this creates the negative pressure needed for a second transfer of dye to the petiole. Although Alexa-BSA fluorescence was low following delivery to the roots, Biphasic kinetics is also noted. Interestingly, the first phase of Alexa-Histone transfer to upper leaves occurs within the first 10 min (compare Fig. 1Cand D) and the second phase is between 30 and 60 min. The Alexa-Histone reaches saturation in L4 petioles at 60 min (Fig. 1B). Possibly after 30 min, the dye or proteins diffuse to the apoplast or nonvascular tissues and this causes negative pressure leading to the second increase in uptake. We also noticed faint CF dye or Alexa-Histone fluorescence in some mesophyll cells. A second explanation is that the sap pressure inside the phloem is not constant and so there are periods of sap movement followed by static periods.

CF dye, Alexa-BSA and -Histone vary in their accumulation in petiole sections. Alexa-BSA follows a slow linear uptake in the central vascular bundle and reaches 14% of CF dye. (Fig. 1C). When Alexa-Histone was applied to the L1 petiole, the maximum fluorescence intensity recorded was 45% of CF dye and reached 90% of CF dye following root delivery (Fig. 1C and D). These data suggest that neither phyllotaxy nor sap flow are the sole factors governing their accumulation in leaf petioles. Perhaps the physical properties of the fluorescent dye and proteins (tertiary structure, charge, molecular mass) influence their mobility.

Protein accumulation in symplast and apoplast

The obvious plateau or decline phases during the 90 min interval (Fig. 1C and D) led us to examine whether fluorescence diffuses into neighboring parenchyma and xylem. Confocal microscopic images of petiole cross sections (Fig. A and B) showed little movement of CF dye beyond the phloem into surrounding parenchyma. Alexa-BSA does not significantly enter the phloem when it is applied either to the roots or L1 petioles (Fig. 2A and B). Fluorescence is mainly in xylem tracheary elements. These observations also correlate with the low level of trafficking depicted graphically in Figure 1C and D. Alexa-Histone fluorescence occurs in the phloem, xylem and parenchyma (Fig. 2A and B). Fluorescence does not appear in intercellular spaces suggesting that Alexa-Histone follows a symplastic route for long-distance transport. There was greater diffusion of Alexa-Histone to surrounding tissues when it was applied to the L1 petiole than to the roots and this correlates with the decline or plateau between 30–60 min reported in Figure 1C.

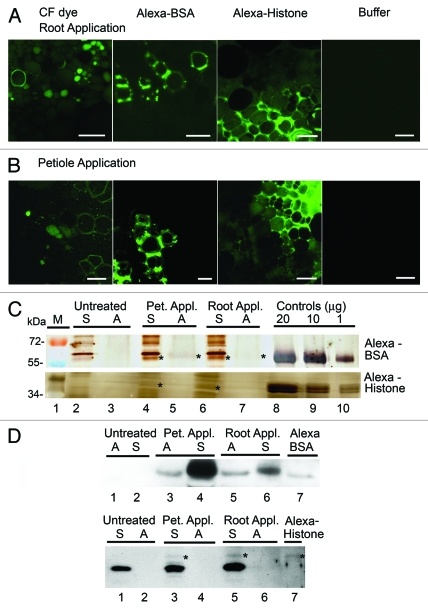

Figure 2.

Analysis of symplastic and apoplastic accumulation of Alexa- BSA and Alexa-Histone H1 in N. benthamiana leaf. (A, B) Confocal microscopic images of CF dye, Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone H1 in N. benthamiana petiole cross sections following application (A) or petiole (B) application. Bar = 50μm. CF dye fills the phloem and is barely visible in xylem or parenchyma cells. Alexa-BSA was mainly in the tracheary elements of the xylem. Alexa-Histone spreads beyond the phloem into parenchyma cells. Control samples were treated with buffer and show no fluorescence. (C) Silver stained SDS-PAGE gel show accumulation of Alexa-BSA and -Histone at 90 min. Apoplastic wash fluids (A, lanes 3, 5, 7) and cell extracts (S, lanes 2, 4, 6) were pooled from L3 and L4 leaves. For Alexa BSA gel, asterisks in each lane shows Alexa-BSA in both the symplastic (S) and apoplastic (A) extracts. Alexa-BSAwas directly loaded to gel and produces a band around 66 kDa. For Alexa-Histone, asterisks in lanes show Alexa-Histone in the symplast but not apoplast wash fluid. Alexa Histone control band is around 34 kD. Loading amounts (μg) for Alexa-BSA and –Histone are indicated above the lanes. (D) Immunoblot probed with polyclonal antisera detecting BSA and Histone. Pet. Appl, petiole application; Root Appl, root application; M, marker; Asterix indicates larger Alexa-Histone band. Plant endogenous histone H1 also detected by antisera.

To discover if Alexa-BSA or -Histone are exported to the apoplast, L3 and L4 leaves were infiltrated with 2-[N-morpholino]ethansesulfonic acid (MES) buffer and the apoplast wash fluids were pooled. Remaining tissue was ground and both samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2C) and silver staining or immunoblot. Alexa-BSA associated with both apoplast wash fluids and cellular extracts (Fig. 2D). Both the silver stained gel and immunoblot show that Alexa-BSA reaches the L3 and L4 petiole via a symplastic or apoplastic route. In contrast, Alexa-Histone is mainly in tissue extracts and not in the apoplastic wash fluids. The Alexa-Histone migrates to a position in the gel that is slightly higher than the 34 kDa molecular weight marker because of the Alexa fluor conjugate affects its migration through the gel (Fig. 2D). A second band on the immunoblot corresponds to plant endogenous histones that cross-react with the same antisera.

Interestingly, Alexa-BSA was exported to the apoplast while Alexa-Histone was restricted to the symplast. These data suggest a sorting mechanism in the phloem. One possibility is that Alexa-Histone resembles plant endogenous histones and is recognized as an endogenous protein, whereas Alexa-BSA is clearly exogenous and this could trigger a mechanism for export to the apoplast. Further research is needed to more accurately compare the destinations of endogenous and exogenous proteins.

Protein transfer to upper leaves of soil grown plants

Phloem delivery of CF dye to an importing leaf is governed by phyllotaxy, whereby carbon-based molecules transferred via the phloem reaches the closest leaves sooner than distal leaves (Roberts et al., 1997). However, we do not know if the exogenous proteins move to specific destinations or if their transport is also governed by phyllotaxy. Here the transport of CF dye, Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone was monitored at 10, 30, 60, and 90 min by examining cross sections of L1-L5 petioles. Control plants were treated with buffer only.

The first observation is that CF dye, Alexa-BSA, or Alexa-Histone reached all leaves simultaneously when they are applied to N. benthamiana roots. The second observation is that transport is biphasic (Fig. 3A). There is an early uptake phase followed by a plateau or decline in fluorescence, and then a second phase of uptake. With respect to CF dye and Alexa-BSA, the first peak occurs at 30 min followed by a slight decline. The transport rate for CF dye is 0.0071 × 105 FU/s and Alexa-BSA is 0.001 × 105 FU/s. The second increase in fluorescence intensity occurs between 60 and 90 min and the fluorescence intensity slightly exceeds the maximum recorded at 30 min. The second phase transport rate for CF dye is 0.0031 × 105 FU/s and Alexa-BSA is 0.001 × 105 FU/s. Thus transport of BSA is slower than CF dye in both phases.

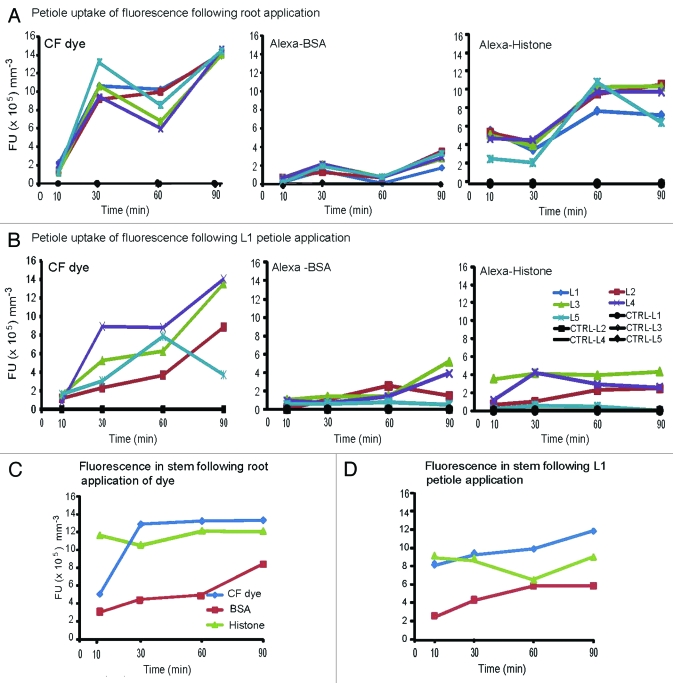

Figure 3.

Fluorescence intensity of petiole and stem cross sections of soil grown N. benthamiana. Graphs depict the average fluorescence values in the central vascular bundles of (n = 4) petiole or stem cross sections. The central vascular bundle were selected as ROIs using Image J software and fluorescence values were recorded. Graphs depict the average values. The data were collected at 10, 30, 60 and 90 min after application of CF dye, Alexa-BSA or - Histone.

The biphasic transfer of Alexa-Histone occurs earlier than the other two samples (Fig. 3A). The first uptake phase occurs within 10 min and the rate of transfer for the first phase is 0.0404 × 105 FU/s. Alexa-Histone uptake reaches a second maximum between 30 and 60 min that is comparable to the saturating levels reported for CF dye at 30 min. The rate for the second phase of uptake is 0.0033 × 105 FU/s. Given that the first phase of Alexa-Histone transfer to upper leaf petioles is faster than CF dye transfer, protein size relative to CF dye is not likely to be the defining feature for the first uptake phase. We cannot also consider apoplastic unloading as a positive factor for long-distance transport since Alexa-Histone is restricted to the symplastic domain. Perhaps the ability of Alexa-Histone to spread further into surrounding tissues increases the pressure gradient within the sieve tube and increasing its uptake.

While phyllotaxy mainly governs transport following root application, orthostichy governs transport following L1 petiole application. Thus first peak fluorescence occurs at 30 min in the L3 and L4 leaf petioles (5.3 × 105 FUs and 8.9 × 105 FUs respectively) located on the same side as the L1 source leaf.11,18 L2 and L5 leaves are located opposite of L1 in the plant and show lower fluorescence (2.3 × 105 FUs and 3.1 × 105 FUs respectively) (Fig. 3B). CF dye transport is biphasic but the values within the first 60 min are lower than reported following root application (compare Fig. 3A and B). Alexa-BSA does not show significant improvement in its ability to move into distal leaves. Alexa-BSA has a low maximum (2.6–5.2 × 105 FUs) at 60–90 min with minimal protein reaching L5 leaves (0.6 × 105 FU). Movement of Alexa-Histone is less extensive following L1 than root application. At 30 min following application of Alexa-Histone to the L1 petiole, fluorescence in L3 and L4 reaches 2.9–3.9 × 105 FUs and then reaches a plateau. These data suggest that uptake is not biphasic. Uptake by L2 leaves is slower and reaches a plateau at 60 min.

To assess the flow of fluorescence from the stems into the petioles, we compared the fluorescence intensities in both locations. Stem sections were cut just below the L1 petiole and the average fluorescence intensities were determined from several individual vascular rays. We predicted that similar levels in the stems and petioles would suggest that the flow is constant, not interrupted, between these two organs. If the fluorescence is lower in the petioles than in the stem, then dye or protein import into the leaves is regulated along the vascular traces diverging from the stem. If the fluorescence is higher in the petioles than in the stems, then the petioles and leaves likely present higher sink strength and the flow is increased into the petioles.

Figure 3C and D shows the fluorescence intensities of CF dye, Alexa-BSA, and Alexa-Histone in stem cross sections. At 30 min, the levels of CF dye in the stem and petioles were comparable. The levels of Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone in the stem were greater than in the petioles, regardless of root or petiole application (around 10 × 105 FU for CF dye and Alexa-Histone, around 6 × 105 FU for Alexa- BSA). These data argue that the petiole restricts movement of proteins, but not CF dye into leaves.

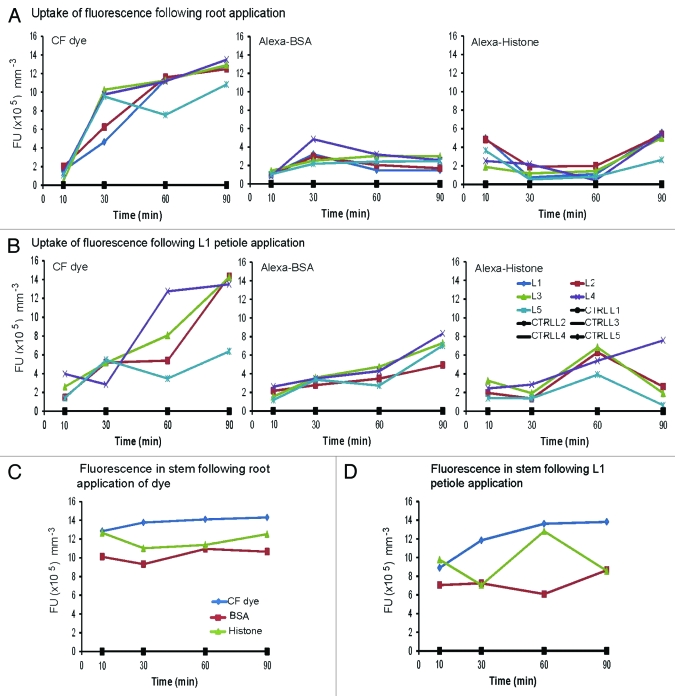

Protein transfer to upper leaves of hydroponic plants

N. benthamiana plants kept in hydroponic medium have greater water content and sap flow through the vasculature than plants grown in soil.19 If sap flow controls the timing and extent of dyes and proteins moving into the petioles then, we expect to see higher fluorescence in the petioles of plants maintained in hydroponic medium. Table 1 compares the real fluorescence values obtained from petiole cross sections at 10 and 90 min. Surprisingly, CF fluorescent values are less than 2-fold different among soil and hydroponically grown plants. These data suggest that higher water application does not stimulate CF dye transfer to all petioles. When Alexa-BSA and -Histone were applied to L1 petioles, uptake was stimulated at 10 and 90 min among hydroponically grown plants delivering 2- to 5-fold greater fluorescent proteins to most petioles. When samples were applied to the roots, we failed to see a change in uptake of CF dye or Alexa-Histone within the first 10 or 30 min of application. For Alexa-BSA, there was an initial 2- to 5-fold greater peak in fluorescence in L1, L3, and L5 petioles at 10 and 30 mi. These values declined over time and there were no real differences by 90 min (Fig. 4A and Table 1). These data argue that water content in the vasculature enables the initial transfer of dye and proteins from source leaves to younger petioles, but has less of an impact on transport from the roots (Fig. 4A and B, and Table 1).

Table 1. Fluorescence unit for CF, Histone and BSA uptaking by N. benthamiana petioles at 10min and 90min.

| Petiole Application (x105) | Root Application (x105) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

10 min |

|

L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

L1 |

L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

| CF |

soil |

1.17 ± 0.11 |

1.60 ± 0.09 |

0.81 ± 0.29 |

1.63 ± 0.31 |

2.09 ± 0.00 |

1.35 ± 0.42 |

1.11 ± 0.10 |

1.94 ± 0.02 |

1.13 ± 0.00 |

| |

hydro |

1.48 ± 0.46 |

2.61 ± 0.02 |

3.97 ± 0.49 |

1.38 ± 0.21 |

1.57 ± 0.46 |

2.00 ± 0.43 |

0.40 ± 0.01 |

1.37 ± 0.08 |

1.10 ± 0.06 |

| Histone |

soil |

0.68 ± 0.09 |

3.51 ± 0.32 |

1.18 ± 0.06 |

0.18 ± 0.01 |

5.76 ± 2.04 |

5.51 ± 1.50 |

5.27 ± 0.64 |

4.89 ± 0.25 |

2.71 ± 0.59 |

| |

hydro |

1.96 ± 0.03 |

3.27 ± 0.91 |

2.44 ± 0.03 |

1.39 ± 0.30 |

4.99 ± 0.09 |

4.83 ± 0.18 |

1.88 ± 0.23 |

2.53 ± 0.05 |

3.64 ± 0.00 |

| BSA |

soil |

0.05 ± 0.06 |

1.04 ± 0.06 |

0.94 ± 0.08 |

0.58 ± 0.17 |

0.20 ± 0.05 |

0.71 ± 0.12 |

0.70 ± 0.08 |

0.68 ± 0.03 |

0.16 ± 0.07 |

| |

hydro |

2.17 ± 0.32 |

1.54 ± 0.13 |

2.62 ± 0.21 |

1.17 ± 0.00 |

1.01 ± 0.00 |

1.01 ± 0.02 |

1.44 ± 0.07 |

0.86 ± 0.13 |

1.02 ± 0.10 |

|

90min |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CF |

soil |

8.86 ± 0.31 |

13.53 ± 0.09 |

14.05 ± 0.08 |

3.73 ± 0.00 |

13.11 ± 0.19 |

13.41 ± 0.05 |

13.23 ± 0.10 |

13.82 ± 0.09 |

13.63 ± 0.00 |

| |

hydro |

14.35 ± 0.31 |

14.27 ± 0.11 |

13.50 ± 0.03 |

6.37 ± 0.00 |

12.82 ± 0.14 |

12.48 ± 0.12 |

12.90 ± 0.08 |

13.50 ± 0.27 |

10.83 ± 0.00 |

| Histone |

soil |

1.34 ± 0.24 |

5.49 ± 0.22 |

2.40 ± 0.17 |

0.21 ± 0.12 |

7.46 ± 0.49 |

10.79 ± 0.41 |

10.55 ± 0.50 |

9.98 ± 0.75 |

6.66 ± 0.00 |

| |

hydro |

2.64 ± 0.40 |

1.91 ± 0.26 |

7.58 ± 0.74 |

0.63 ± 0.00 |

5.59 ± 0.99 |

5.38 ± 0.54 |

5.00 ± 0.12 |

5.34 ± 0.00 |

2.65 ± 0.00 |

| BSA |

soil |

1.49 ± 0.04 |

5.20 ± 0.78 |

3.93 ± 0.76 |

0.56 ± 0.00 |

1.74 ± 0.17 |

3.54 ± 0.46 |

2.66 ± 0.61 |

2.84 ± 0.25 |

3.30 ± 0.36 |

| hydro | 4.94 ± 0.48 | 7.30 ± 0.15 | 8.32 ± 0.84 | 7.02 ± 0.61 | 1.46 ± 0.08 | 1.70 ± 0.31 | 3.02 ± 0.01 | 2.57 ± 0.02 | 2.44 ± 0.30 | |

CF, Histone and BSA are used for uptaking measurement. There are four application methods for each of CF, Histone and BSA: soil grown, petiole application; soil grown, root application; hydroponic, petiole application and hydroponic, root application.

Fluorescence unit of 10min and 90min uptake by petioles are listed in this table. L1, L2, L3, L4, L5 means the leaf petiole of L1, L2, L3, L4, L5.

Each of the value is the average of the fluorescence unit value of bottom part (branch out from stem) and top part (before reach to leaf) of that exact petiole.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence intensity of petiole cross sections of N. benthamiana which were transferred to hydroponic system. Graphs depict the average fluorescence values in the central vascular bundles of (n = 4) petiole or stem cross sections. The central vascular bundle were selected as ROIs using Image J software and fluorescence values were recorded. The data were collected at 10, 30, 60 and 90 min after application of CF dye, Alexa-BSA or - Histone.

Measure of the velocity of protein transport in phloem using MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology was employed to study vascular flow as well as anatomical position.20-23 This technology is nondestructive and noninvasive and is valuable for measuring vascular transport of MRI tracers (heavy water and gadolinium) or proteins in intact plants.23

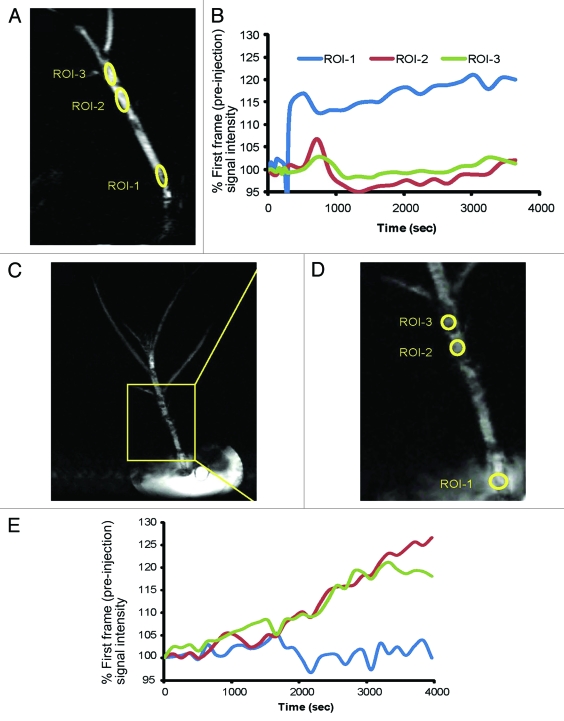

Gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA; 4.7mg/ml) and biotinyl-bovine serum albumin-gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-BSA; 1mg/ml) were delivered to the roots of N. benthamiana plants in hydroponic medium.23-25 Three regions of interest (ROI-1, ROI-2, and ROI-3) were selected in the stem between the root and L1 leaf (Fig. 5A, C and D). We compared the signal intensity within a given region of interest (ROI) at different time points to the signal intensity of pre-delivery of Gd-DTPA or Gd-BSA at the same ROI. We noted that ROIs located at a longer distance from the root produced later peaks, as expected (Fig. 5B and E). Gd-DTPA reached a relatively high steady-state after 1000 sec (Fig. 5B) in ROI-1, which is located at the base of the stem. The signal intensity in ROI-1 remained fairly constant over time. This pattern of uptake suggests that ROI-1 represents a reservoir feeding into the next ROIs. ROI-2 and- 3 reveal transitions that fail to become saturated with signal (Fig. 5B). Evidence of a peak followed by a decline might be due to the contrast agent moving through the region or leaking out of the vasculature into adjacent tissues.

Figure 5.

Axial molecular transport in the stem of N. benthamiana visualized by MRI by means of the 4.7 mg/ml Gd-DTPA and 1 mg/ml Gd-BSA tracer absorbed by the root. (A, C, D) Gd-DTPA or Gd-BSA treated N. benthamiana plants. ROI-1 was the point adjacent to stem-root interface. ROI-2 and -3 were points further away from root, below the L1 petiole. (C) Image of whole N. benthamiana plant which was treated with Gd-BSA and the yellow box indicates the stem region analyzed in panel (D). (B, E) Charts show the Gd-DTPA and Gd-BSA signal intensities for each ROI. Values at each time point were normalized with the original pre-injection signal intensity of that ROI. Peaks for ROI-1 precede ROI-2 and -3.

The signal intensities produced by Gd-BSA in each ROI were unlike Gd-DTPA. The signal intensity of Gd-BSA in ROI-1 (Fig. 5E) reached a peak at a time (640 sec) later than for Gd-DTPA (520 sec) pointing to slower uptake. In fact, Gd-BSA moved between ROI-1 and ROI-2 at a velocity of 0.057 mm/s, which is slower than 0.077 mm/s for Gd-DTPA (Fig. 5A and B). At 1700 sec, ROI-2 and -3 increased over time while ROI-1 declined, indicating that Gd-BSA moved out from ROI-1 and moved into ROI-2 and -3. Thus, ROI-1 represents a transition rather than a reservoir for protein moving from the root. There is clearly forward movement of Gd-BSA into ROI-2 and -3 which is represented by the continuous increase in these locations, whereas Gd-DTPA declines at the similar position (compare Fig. 5B and E). Although Gd-BSA moves at a velocity of 0.008 mm/s between ROI-2 and -3, which is much slower than the 0.024 mm/s velocity for Gd-DTPA. Gd-BSA in ROI-1 reaches a steady-state suggesting an equilibration of uptake, and this may be impacted by movement of the BSA conjugate into the apoplast (Fig. 5E).

These data suggest that the transfer of Gd-BSA was slower than Gd-DTPA in N. benthamiana stems between the roots and L1 leaf petiole. These data corroborate information obtained using fluorescence intensity measures of stem cross sections.

Unloading of CF dye, Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone in leaf veins

In N. benthamiana leaves, a prominent midrib, or “class I vein” extends from the petiole to the leaf apex. N. benthamiana leaves have the netted vein pattern, smaller veins which have several distinctive vein size classes that branch from the larger veins. Class II veins branch from class I. Class III veins are major veins that branch from class II veins. Class IV and V are minor veins that branch from class III and can be quite small in diameter.11,26,27

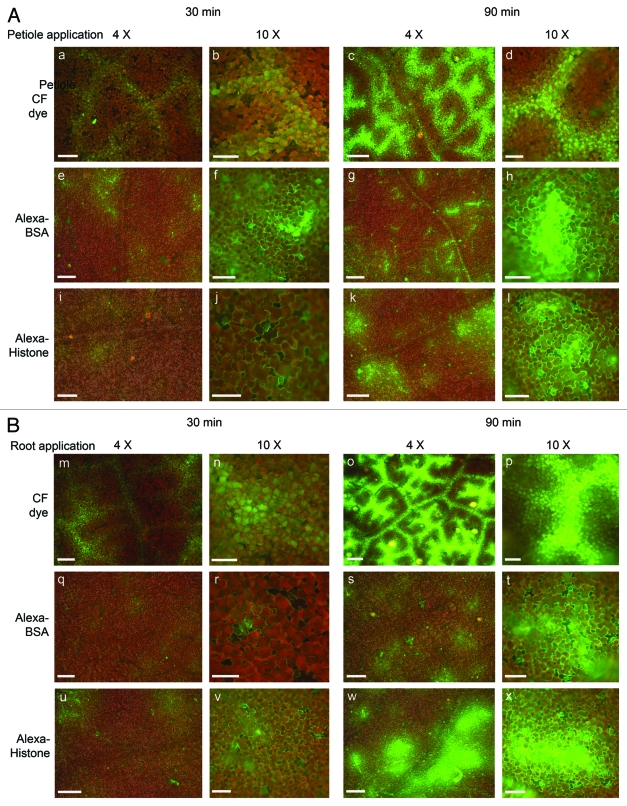

After dye or protein application, the leaves were detached from plant at various times for observation. Figure 6 shows the vascular patterns produced by CF dye, Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone fluorescence in L5 leaves at 30 and 90 min. Regardless of whether CF dye was applied to the roots or L1 petiole, class I, II and III veins of L5 leaves became heavily labeled at 30 min (Fig. 6A andB and M and N). At 90 min, the fluorescence grew in intensity, as though dye was bleeding out of class III veins (Fig. 6C and D, O and P)11 into surrounding cell layers. As reported previously, class III veins were the function unloading vein for CF dye in sink leaves.

Figure 6.

Unloading pattern of CF dye (A-D), Alexa Fluor 488 BSA (E- H) and Alexa Fluor 488 Histone (I-L) in L5 sink leaf following L1 petiole application. Unloading pattern of CF dye (M-P), Alexa Fluor 488 BSA (Q-T) and Alexa Fluor 488 Histone (U-X) in L5 sink leaf following root application Images were taken at 30 and 60 min. At 30 min CF dye is mainly inside veins. Fluorescence unloads into neighboring cells at 60 min and produces a “bleeding” pattern around the class II and III veins. Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone are seen in leaf lamina, completely unloads from veins. Bars in images taken at 4x magnification = 500μm; Bars in images taken at 10 x magnification = 100 μm.

Alexa-BSA and -Histone were not obvious in class III or minor veins at 30 min, but there were discrete fluorescence spots in mesophyll and epidermal cells (Fig. 6E, F, I, J, Q, R, S and V). At 90 min, there was an apparent accumulation of fluorescence in class II and III veins (Fig. 6G and K) as well as along the leaf lamina (Fig. 6H, L, S, T, W and X). These indicate that Alexa-BSA and –Histone unloaded from major veins.

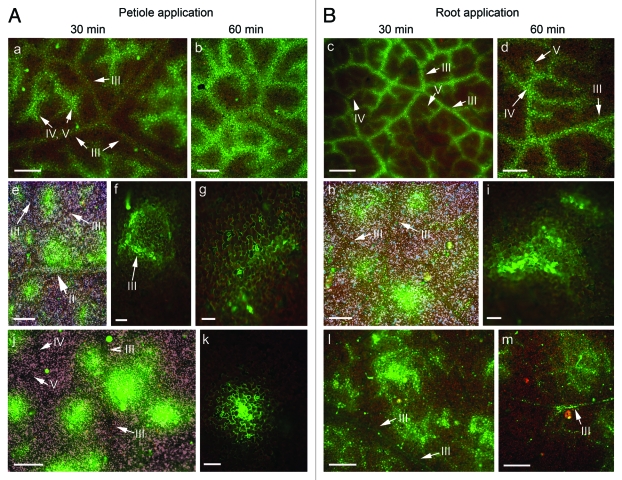

In source/sink transitional leaves, CF dye appears to bleed from class III, IV and V veins (Fig. Seven a-d). Lateral bleeding of class IV and V veins are more apparent than class II veins (Fig. 7A, C) at 30 min, but at 60 min all veins show similar pattern. These imply that different vein classes function are developmentally controlled in sink and source leaves.11 Class IV and V veins become functional for unloading as leaves mature. However, phloem unloading of Alexa-BSA and –Histone in source/sink transitional leaves resembles the pattern reported for sink leaves. Fluorescence was obvious in areas adjacent to class II and III veins at 30 min and was primarily in mesophyll and epidermal cells (Fig. 7E-H). Following root application, minor amounts of Alexa-Histone was seen in class III veins (Fig. 7L and M).

Figure 7.

Leaf vascular pattern in L4 source/sink transition leaf following application of CF dye, Alexa -BSA or Alexa -Histone. Images were taken at 30 or 60 min following petiole or root application of fluorescent markers. Class II, III, IV, and V veins are identified in some panels. (E, H, J) are image overlays showing bright field and fluorescent images of veins and fluorescent proteins. Bars in (A, C, E, H, J, and L) = 500μm; Bars in (B, D, F, G, I, K, and M) = 100 μm.

Fluorescence intensity in petioles of Fluorescein-HCV treated plants and HCV unloading pattern in leaves

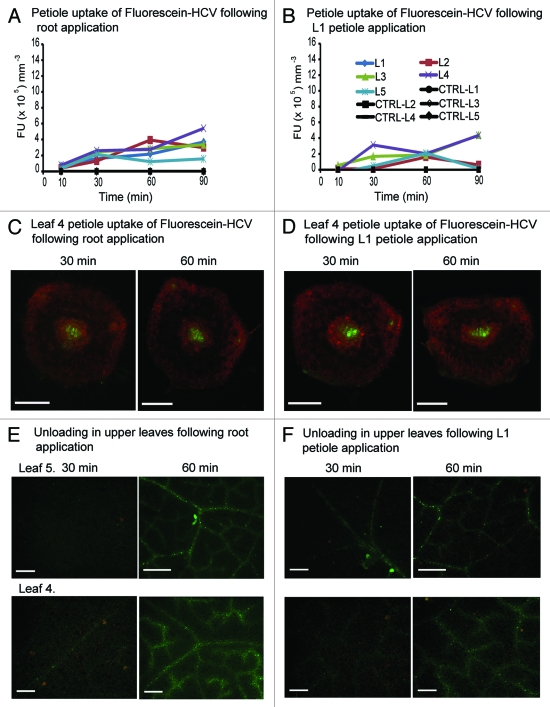

The association of virus cores with plant material has garnered attention in recent years as outbreaks of human enteroviruses associating with raw vegetables have been reported.28 Research has shown that Hepatitis A virus can survive on the surface of fruits and vegetables.29 Contamination occurs either by irrigating plants with fecal contaminated groundwater or by infected food handlers. While Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is not considered to be foodborne, we decided to test commercially available HCV core antigen [2–192]-galactosidase-tagged, fluorescein conjugate (Fluorescein-HCV) to learn if it can be taken up by the plant vasculature, in a manner similar to other exogenous proteins. Fluorescein-HCV has a molecule weight of 136 kDa which is comprised of the 22kDa HCV core antigen plus 114kDa galactosidase-tagged. Given that the molecule is much larger than the 66 kDa Alexa-BSA, we predicted that if size were the determining factor for phloem transport, then its ability to move in the phloem should be restricted in comparison to Alexa-BSA.

When HCV was applied to N. benthamiana roots, there was a fairly slow linear uptake of fluorescence to all leaves. Fluorescence intensities at 60 min were approximately 2-fold higher than reported for Alexa-BSA (compare Fig. 8A with Fig. 3A). Almost all leaf petioles showed a decline in fluorescence after 30 min. Thus root application leads to a greater general increase that is sustained over time.

Figure 8.

The uptake of fluorescein-HCV core antigen by N. benthamiana petioles and leaves. (A,B) Graphs depict the average fluorescence values in the central vascular bundles of (n = 4) petiole sections. The central vascular bundles were selected as ROIs using Image J software and fluorescence values were recorded. The data were collected at 10, 30, 60 and 90 min after application of fluorescein-HCV. (C, D) Petiole uptake of Fluorescein-HCV following L1 petiole delivery. Images of L 4 petiole cross sections of N. benthamiana following L1 petiole (a) or root (b) application at 30 and 60 min. Bars = 500 μm. (E, F) Leaf vascular pattern in L4 source/sink transition leaf or L5 sink leaf. Images were taken at 30 or 60 min following root or petiole application of fluorescent markers. Bars = 500μm.

Surprisingly, the low fluorescence levels in L4 petioles implies that the Fluorescein-HCV is not taken up by sink leaves (Fig. 8B).11 However, microscopic examination of L4 and L5 leaf segments revealed fluorescein-HCV in leaf veins at 30 and 60 min. Figure 8E and8F show the bleeding pattern surrounding veins is similar as CF dye. The low fluorescence intensity indicates that the unloading of HCV is much slower than CF dye. In both L5 sink leaves and L4 source/sink transition leaves, the unloading occur in class III veins (Figs. 8E and8F). Although minor veins function to unload CF dye in L4 source/sink transition leaves, they do not function for fluorescein-HCV unloading. Interestingly, fluorescein-HCV does not unload from the veins. This is unlike Alexa-BSA or Alexa-Histone suggesting that there is a specific restriction in HCV core antigen movement.

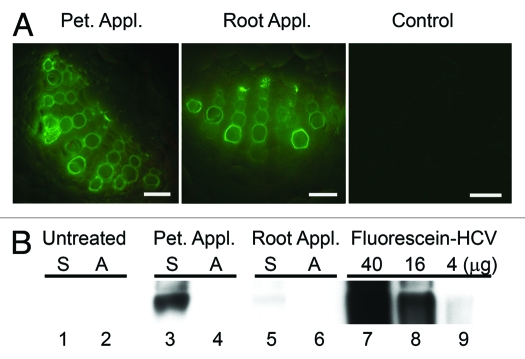

Given the low accumulation of fluorescein-HCV we hypothesized that this protein performed similar to Alexa-BSA and might be exported to the apoplast. We examined petiole cross sections under high magnification and determined that more fluorescence was associated with xylem than phloem (Fig. 9A). Leaves were infiltrated with 2-[N-morpholino]ethansesulfonic acid (MES) buffer and the apoplast wash fluids were pooled. Remaining tissue was ground and both samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (Fig. 9B). Bands were detected mainly in tissue extracts not in the apoplastic wash fluids. We noted greater accumulation of fluorescein-HCV following loading of the L1 petiole than root loading.

Figure 9.

Fluorescein-HCV core antigen in N. benthamiana petioles and extracts. (A) Images of L 4 petiole cross sections of N. benthamiana following L1 petiole (a) or root (b) application at 30 and 60 min. Bars = 500μm. (B) Immunoblot probed with polyclonal antisera detecting HCV capsid protein. Pet. Appl, petiole application; Root Appl, root application.

Interestingly, the cumulative data shows that each protein is sorted differently in the phloem Alexa-BSA was exported to the apoplast while Alexa-Histone was restricted to the symplast. Alexa-Histone and -BSA unload into the leaf lamina while fluorescein-HCV is restricted to leaf veins. These data suggest that there is a sorting mechanism for proteins in the phloem.

Discussion

We employed four different size fluorescent molecules to study transfer from the site of application in the roots and L1 petiole to the L4 and L5 leaves: CF dye (460 Da), Alexa-Histone (34 kDa), Alexa-BSA (66 kDa), and fluorescein-HCV (136 kDa). When CF-dye and Alexa-Histone are applied to the roots, they moves extensively throughout the plant, but the larger Alexa-BSA and fluorescein-HCV show minimal movement into L4 leaves, as determined from petiole cross sections (Figs. 1, 3, 4, and8). While the transfer rates over 90 min for the larger proteins appear to be slow, the intensity of fluorescence is adequate to detect proteins in leaf veins and lamina. Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone produce low levels of fluorescence in major veins and appear to completely unload into the leaf lamina. Thus regardless of the protein dimensions and the intensity of fluorescence in distal parts of the plant, there does not appear to be an obvious barrier preventing extensive movement of exogenously applied proteins within the vasculature.

If we consider only the first uptake phase that occurs within 10 min or 30 min following application of CF dye or proteins, it is interesting to note that Alexa-Histone is larger than CF dye and its initial transfer to the petioles is more rapid. These data suggest that protein size relative to CF dye is not the defining feature for the first uptake phase. We cannot also consider apoplastic transport as a positive factor for long distance movement of Alexa-Histone since it appeared to be restricted to symplastic domain and was not recovered in the apoplastic wash fluid. Perhaps the ability of Alexa-Histone to unload from the phloem into neighboring cell layers affects the pressure gradient within the sieve tube and increasing its uptake. Beyond the 30 min time frame, Alexa-Histone showed less movement into the upper leaf petioles when it was applied to plants maintained in hydroponic medium. These data suggest that water potential is not the driving force for Alexa-Histone movement. We also noted that when Alexa-Histone was applied to the L1 petioles its movement was generally reduced in comparison to when it is applied to the roots, especially within the first 10 min. These observations are harder to explain. Perhaps the vascular dimensions of the L1 petiole are different than from the roots and this changes the transfer potential or rate to distal parts of the plant. Another possibility is that the vascular trace at the juncture of the L1 petiole and stem downregulates the rate export from the leaf in comparison to phloem traces moving from the roots into the stem.

The notion that the petiole regulates flow to and from the stem is supported by data in Figures 3and 4. In panels c and d of both figures we see that the amount of fluorescence in the stem vascular rays is higher than in the leaf petioles. Assuming that these vascular rays branch into the petioles we would expect to see similar intensities if there was a seamless transition. It is possible that there is a change in the dimension of the phloem strands that transition from the stem into the petiole and this controls the amount of proteins that enter or exit the petiole. There might also be a regulatory mechanism that has not yet been described that sorts proteins to different destinations. Currently we lack the investigative tools to examine the existence of such a mechanism in N. benthamiana plants.

While fluorescence in petiole cross sections suggests low movement of Alexa-BSA through the stem, MRI was used to quantify the transport rate which is within the range predicted by other studies. MRI technology is widely used for studying vascular transport in mammalian systems and has been employed in few plant biology studies to describe flow dynamics as well as anatomical structures.20-22 MRI has been used for studying the long distance water transport in cucumber plants under normal and environmental stress conditions. Heavy water and gadolinium have been loaded into the vasculature as MRI tracers to quantify the flow velocities in Pharbitis nil (morning glory).23 Since plants are largely composed of water molecules which each contain two hydrogen nuclei or protons. When we put plants inside the powerful magnetic field of the scanner, the magnetic moments of these protons align with the direction of the field. A radio frequency electromagnetic field is then briefly turned on, causing the protons to alter their alignment relative to the field. When this field is turned off the protons return to the original magnetization alignment. These alignment changes create a signal which can be detected by the scanner. With the use of a Gd-based contrast agent, this technology can be used to non-destructively and non-invasively measure vascular transport in intact plants.

Our research is the first to use MRI to examine protein movement. The velocity measurements show significant rates of transport near the site where the contrast agent and/or protein is applied, and as the ROIs move further away the rates drop. The rate of Gd-BSA movement (0.057 mm/s) is slower than that for Gd-DTPA (0.077 mm/s), as predicted by the fluorescence data. The ability of MRI and fluorescence data to concur on BSA transport through the stem, lends credibility to the approach developed in this study, of measuring fluorescence intensities in cross sections over time. While MRI measures signal intensities in digital ROIs, cross sections were employed as ROIs and fluorescence levels were measured directly in the vasculature tissues. MRI technology is powerful technology and has the ability to obtain valuable profiles of protein movement through the phloem and is a useful alternative to studying protein mobility in the phloem.

It was also interesting to note differences between the central and lateral vascular bundles in petioles. CF dye moved in both the central and adaxial vascular bundles, while Alexa-BSA, -Histone, and Fluorescein-HCV were mainly in the central vascular bundle. These data suggest that the adaxial vascular bundles preferentially transport solutes and not proteins. There is very little known about the vascular continuity between the petiole and leaf lamina in Nicotiana ssp. The adaxial position of the lateral veins suggests that they connect to the leaf lamina.17 More research is needed to know if they differ in their capacity for photoassimilate or protein transport. For example, photosynthetic cells surround the central vascular bundle and this region shows intensive chlorophyll accumulation.30 We do not know if there is comparable chlorophyll accumulation around the adaxial veins. It would be intriguing to learn the influence of the photosynthetic cells on photassimilate or macromolecular loading into the adaxial veins.

It was particularly intriguing to see the leaf patterns for Alexa-BSA, -Histone, and fluorescein-HCV were unique to each of the proteins and that they did not display the same pattern as CF dye for movement into minor veins, or unloading to the mesophyll. These data suggest that there is a protein sorting mechanism associated with leaf veins. CF dye is an indicator used to differentiate sink, source/sink transition, and source leaves. In sink leaves, CF dye enter major and minor veins, and can bleed into surrounding tissues, mainly from major veins. Alexa-BSA and –Histone appeared to completely unload from the major veins in sink leaves. There were minimal proteins left in small regions of the leaf veins. Fluorescence was prominent in the epidermal and mesophyll cells and on rare occasions we could see some fluorescence highlighting major veins (Fig. 6). These outcomes were surprising because we expected to observe similarities with CF dye in vascular accumulation. The fact that both proteins were largely removed from the veins suggests that there is a mechanism that clears exogenous proteins. Such a mechanism might be related to defense machinery, operating to reduce the level of toxic or foreign proteins in the plant vascular system.

It was particularly interesting to note that fluorescein-HCV core protein performed similar to the CF dye. Fluorescein-HCV resided mainly in major and minor veins in sink leaves. There was little evidence of fluorescence moving into neighboring cells. Thus its pattern of movement is unlike the other exogenous proteins that we chose to study. Among plant viruses, there are numerous reports that viruses or coat proteins are restricted to the phloem and can only unload with the aid of a viral movement protein. Furthermore, the insect infecting flock house virus can spread systemically in plants if aided by a plant viral movement protein. These data suggest that there is a mechanism in plants that specifically regulates viral proteins in the phloem. Once the virus core protein is loaded into the phloem it can then spread throughout the plant vasculature. We do not know whether restriction in protein unloading is a defense mechanism limiting virus spread, or if complete vascular unloading, as for BSA and Histone, represents a defense mechanism that clears foreign proteins from the plant vasculature. However the contrasting data raises intriguing questions for future research.

Researchers have reported enteric viruses and hepatitis A are common in vegetables and that contaminated groundwater could be a source for viral outbreaks. These contaminating viruses have been identified using diagnostic criteria and have not fully investigated the penetrance of the viruses into internal tissues. Evidence of HCV core in the plant vasculature sheds new light on the potential uptake of foodborne contaminants by plants. These data are intriguing for two reasons. First, they show that a single viral protein can easily be taken up by an edible plant just by adding the proteins to a hydroponic system. This could be a source of edible vaccines that has never been tested. Second, these data suggest that exogenous proteins, including viral proteins, can follow the flow of assimilates throughout the plant but that there is a mechanism that differentiates foreign proteins for transport to the apoplast, unloading to leaf lamina, or restriction to leaf veins.

Methods

Plant Materials

Nicotiana benthamiana seeds were sown in Metro-Mix and grown in a growth room with 16 h light and 25°C. Plant age was determined by the number of fully expanded leaves, which is 5 to 6 in all the experiments. Some plants were removed from soil, the roots were rinsed in water and then transplanted to hydroponic bags.31,32 Hydroponic bags were placed in the growth room for 24 h prior to each experiment to ensure plants were adapted to the liquid growing environment to ensure maximal water conductivity in all tissue for experiments.

Fluorescence Imaging

To measure mass flow through the stems and into sink petioles and identify loading/unloading veins, the fluorescent compounds were introduced into the roots or petiole of first source leaf (Leaf 1). 60μg/ml 6 (5)-carboxyfluorescein (CF; Sigma) dye was prepared according to standard protocols.11,33 Alexa-Histone H1 (32 kDa; Invitrogen). Alexa-BSA (66 kDa; Invitrogen) were diluted to 0.3mg/ml. Nanodrop spectrophotometer was used to normalize fluorescence intensities of CF dye, Alexa-BSA and Alexa-Histone so we could compare the levels of fluorescence detected in leaf veins.

To apply samples to the L1 petiole, the L1 leaf blade was detach just above the petiole. The cut surface of the petiole was inserted into an eppendorf tube filled with 300μl CF dye, Alexa-BSA or -Histone and secured it using parafilm. Alternatively, we inserted the main root into an eppendorf tube filled with CF dye, Alexa-BSA or -Histone or BSA and secured it using parafilm.

The progression of CF dye or proteins to the upper leaves was monitored using a hand held UV Blue-Ray lamp (UVP, LLC). To quantify CF dye or proteins transport in petiole vasculature, cross sections of the source and sink petioles were imaged using a Nikon E600 epifluorescence microscopy (Nikon Corp.) which contains a 470–490 nm excitation filter, a DM505 dichroic mirror and a BA520 barrier filter with a built-in Magnafire camera. Image J software was used for cross section image analysis, including quantifying the fluorescence units per dimensional vol (FU/mm3).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

A MRI spin labeling sequence was used to characterize flow velocities in the stems, petioles and leaf veins. MRI experiments were performed on a Bruker Biospec 7.0 Tesla / 30 cm horizontal-bore magnet small animal imaging system, a S116 gradient coil, and a 72 mm quadrature volume coil (Bruker Biospin). 4.7mg/ml Gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA, MagnevistR. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.) was delivered to the root of the plant and then its accumulation in the stem, petioles and major veins of sink leaves were followed over time. Gadolinium-based contrast agent is a contrast media used to improve the visibility of internal body structures in MRI. For the study of protein movement in N. benthamiana plant, 1mg/ml Biotinyl-bovine serum albumin-gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-BSA) was used. Gd-BSA was synthesized as previously reported (Towner et al., 2008).

Gd-DTPA or Gd-BSA was applied to N. benthamiana plant by placing roots in one water-filled cup (diameter: 2 cm). A syringe was used to apply Gd-DTPA or Gd-BSA to the tubing connected cup. A larger second tubing which is interrupted with a stop cock valve joint was also inserted into the water filled cup. A bulb is used to push air into the tubing. When the stop cock is open the air enters into the water and this mixes the water and Gd-DTPA or Gd-BSA. The reason for this set up is to inject air into the conical cup to stir the dye into solution while the plant is in the MRI inner chamber. This plant containing apparatus is placed into the MRI inner chamber. Using the apparatus we first injected Gd-DTPA into the roots, then we open the stopcock valve on the second tube. Air was pushed six times into the second tubing and the dye and water are mixed. For stem and petiole experiments, MRI were performed using FLASH sequence with echo time = 7ms, repetition time = 300ms, matrix 384 × 256, field of view = 80mm × 54mm. For leaf vein experiments, MRI were performed using FLASH sequence with echo time (TE) = 6ms, repetition time (TR) = 376ms, matrix 256 × 256, field of view = 80mm × 80mm.

Intercellular Wash Fluid (IWF) Extraction and Protein Extraction from Leaf

Leaves from control, Alexa-BSA or -Histone treated plants were cut and carefully washed with deionized water and blotted dry. Leaves were infiltrated by pushing the plunger of a syringe which contain 1ml 180 mM 2-[N-morpholino]ethane-sulphonic acid (MES) and then blotted again. Leaves were transferred to centrifuge tubes and centrifuged immediately at 230 g, for 4 min at 4°C. The liquid (intercellular wash fluid) in the centrifuge tube was collected for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. The remaining leaf tissue was ground with grinding buffer (100 mM TRIS-HCl (pH7.5), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 400mM sucrose, 10% glycerol and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol) at a ratio of 0.1 g leaf tissue per 100 μl buffer. The intercellular wash fluid and leaf extracts were each diluted with equal volume of Tris-glycine SDS gel loading buffer (Invitrogen) was added. Samples were boiled for 5 min in water-bath, transferred to ice for 3 min, then centrifuged at 13200 rpm for 5 min before loading to SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE, Immunoblot Analysis and Silver Stain

Intercellular wash fluids and leaf extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted to Hybond-P (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using standard protocols.34 Blots were incubated with Histone antibody (1:200 [v/v]; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) or BSA antibody (1:3000 [v/v]; Invitrogen) for 1h. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (GE healthcare) was diluted 1:20000 (for Histone) or 1:50000 (for BSA) served as the secondary antiserum using ECL Advanced protein gel blotting Kit (GE Healthcare). Blots were exposed to film for 10–60 sec. Films were scanned and images are cropped with scanner CanonScan 9950F and associated program Arcsoft Photo Studio 5 (Canon USA).

Gels were stained with silver using standard protocols.34 Gels were incubated in 45ml fixative solution (30% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) for 12h at room temperature with gentle shaking. After discarding the fixative, gels were incubated twice in five vol of 30% ethanol for 30 min. After discarding the ethanol, gels were rinsed four times with 10 vol ddH2O for 10 min. Then gels were immersed in five vol of 0.1% AgNO3 (freshly diluted from 20% AgNO3) for 30 min and washed under a stream of ddH2O for 20 sec on each side. Gels were immersed in five vol of freshly made developer (2.5% sodium carbonate, 0.02% formaldehyde) for few min. After the bands appeared on the gel, the reaction was quenched by washing in 1% acetic acid for a few min. Then the gels were washed several times with ddH2O for 10 min.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Oklahoma Center for Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) Plant Biology Program contract no. 7331.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/17896

References

- 1.Oparka KJ, Cruz SS. THE GREAT ESCAPE: Phloem Transport and Unloading of Macromolecules1. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:323–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lough TJ, Lucas WJ. Integrative plant biology: role of phloem long-distance macromolecular trafficking. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:203–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang NC, Yu TS. The sequences of Arabidopsis GA-INSENSITIVE RNA constitute the motifs that are necessary and sufficient for RNA long-distance trafficking. Plant J. 2009;59:921–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathieu J, Warthmann N, Kuttner F, Schmid M. Export of FT protein from phloem companion cells is sufficient for floral induction in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1055–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buhtz A, Pieritz J, Springer F, Kehr J. Phloem small RNAs, nutrient stress responses, and systemic mobility. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin SI, Chiou TJ. Long-distance movement and differential targeting of microRNA399s. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:730–2. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.9.6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voinnet O, Baulcombe DC. Systemic signalling in gene silencing. Nature. 1997;389:553. doi: 10.1038/39215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadler R, Wright KM, Lauterbach C, Amon G, Gahrtz M, Feuerstein A, et al. Expression of GFP-fusions in Arabidopsis companion cells reveals non-specific protein trafficking into sieve elements and identifies a novel post-phloem domain in roots. Plant J. 2005;41:319–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imlau A, Truernit E, Sauer N. Cell-to-cell and long-distance trafficking of the green fluorescent protein in the phloem and symplastic unloading of the protein into sink tissues. Plant Cell. 1999;11:309–22. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grignon N, Touraine B, Durand M. 6(5)Carboxyfluorescein as a tracer of phloem sap translocation. Am J Bot. 1989;76:871–7. doi: 10.2307/2444542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts AG, Cruz SS, Roberts IM, Prior D, Turgeon R, Oparka KJ. Phloem Unloading in Sink Leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana: Comparison of a Fluorescent Solute with a Fluorescent Virus. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1381–96. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.8.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz-Medrano R, Xoconostle-Cazares B, Lucas WJ. Phloem long-distance transport of CmNACP mRNA: implications for supracellular regulation in plants. Development. 1999;126:4405–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JY, Yoo BC, Rojas MR, Gomez-Ospina N, Staehelin LA, Lucas WJ. Selective trafficking of non-cell-autonomous proteins mediated by NtNCAPP1. Science. 2003;299:392–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1077813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JR, Garcia-Arenal F. The bundle sheath-phloem interface of Cucumis sativus is a boundary to systemic infection by Tomato aspermy virus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1998;11:109–14. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.2.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peleg G, Malter D, Wolf S. Viral infection enables phloem loading of GFP and long-distance trafficking of the protein. Plant J. 2007;51:165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo L, Yu Y, Xia X, Yin W. Identification and functional characterisation of the promoter of the calcium sensor gene CBL1 from the xerophyte Ammopiptanthus mongolicus. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maksymowych AB, Orkwiszewski JAJ, Maksymowych R. Vascular Bundles in Petioles of Some Herbaceous and Woody Dicotyledons. Am J Bot. 1983;70:1289–96. doi: 10.2307/2443419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joy KW. Translocation in Sugar-Beet. I. Assimilation of 14co2 + Distribution of Materials from Leaves. J Exp Bot. 1964;15:485. doi: 10.1093/jxb/15.3.485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Fuchs M, Cohen S, Cohen Y, Wallach R. Water uptake profile response of corn to soil moisture depletion. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:491–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00825.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windt CW, Vergeldt FJ, de Jager PA, van As H. MRI of long-distance water transport: a comparison of the phloem and xylem flow characteristics and dynamics in poplar, castor bean, tomato and tobacco. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:1715–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheenen T, Heemskerk A, de Jager A, Vergeldt F, Van As H. Functional imaging of plants: a nuclear magnetic resonance study of a cucumber plant. Biophys J. 2002;82:481–92. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75413-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheenen TW, Vergeldt FJ, Heemskerk AM, Van As H. Intact plant magnetic resonance imaging to study dynamics in long-distance sap flow and flow-conducting surface area. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1157–65. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.089250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gussoni M, Greco F, Vezzoli A, Osuga T, Zetta L. Magnetic resonance imaging of molecular transport in living morning glory stems. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:1311–22. doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(01)00468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donker HC, Van As H. Cell water balance of white button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) during its post-harvest lifetime studied by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1427:287–97. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Towner RA, Smith N, Doblas S, Tesiram Y, Garteiser P, Saunders D, et al. In vivo detection of c-Met expression in a rat C6 glioma model. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:174–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avery GS. Structure and development of the tobacco leaf. Am J Bot. 1933;20:565–92. doi: 10.2307/2436259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding B, Parthasarathy MV, Niklas K, Turgeon R. A morphometric analysis of the phloem-unloading pathway in developing tobacco leaves. Planta. 1988;176:307–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00395411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheong S, Lee C, Song SW, Choi WC, Lee CH, Kim SJ. Enteric viruses in raw vegetables and groundwater used for irrigation in South Korea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7745–51. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01629-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satter S, Tetro J, Bidawid S, Faber J. Foodborne spread of hepatitis A: Recent studies on virus survival, transfer and inactivation. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2000;11:159–63. doi: 10.1155/2000/805156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hibberd JM, Quick WP. Characteristics of C4 photosynthesis in stems and petioles of C3 flowering plants. Nature. 2002;415:451–4. doi: 10.1038/415451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driskel BA, Hunger RM, Payton ME, Verchot-Lubicz J. Response of Hard Red Winter Wheat to Soilborne wheat mosaic virus Using Novel Inoculation Methods. Phytopathology. 2002;92:347–54. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verchot J, Driskel BA, Zhu Y, Hunger RM, Littlefield LJ. Evidence that soilborne wheat mosaic virus moves long distance through the xylem in wheat. Protoplasma. 2001;218:57–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01288361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Ding B, Baulcombe DC, Verchot J. Cell-to-cell movement of the 25K protein of potato virus X is regulated by three other viral proteins. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2000;13:599–605. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]