Abstract

Objective

To report accuracy of intraocular lens (IOL) power calculations and early refractive status in pseudophakic eyes of infants in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

Methods

Eyes randomized to receive primary IOL implantation were targeted for a postoperative refraction of +8.0 diopters (D) for infants 28 to 48 days at surgery and +6.0 D for ≥49 days to <7 months at surgery using the Holladay 1 formula. Refraction one month after surgery was converted to spherical equivalent, and prediction error (PE=calculated − actual refraction) and absolute PE were calculated. Baseline eye and surgery characteristics and A-scan quality were analyzed to compare their effect on PE.

Main Outcome Measure

Prediction error

Results

56 eyes had primary IOL implantation, 7 were excluded for lack of postoperative refraction (n=5) or incorrect technique in refraction (n=1) or biometry (n=1). Overall mean absolute PE was 1.8 ± 1.3 D and mean PE was +1.0 ±2.0 D. Absolute PE was <1 D in 41% of eyes, but >2 D in 41% of eyes. Mean IOL power implanted was 29.9 D (range, 11.5 D–40.0 D); most eyes (88%) implanted with IOL ≥30.0 D had less postoperative hyperopia than planned. Multivariate analysis showed only short axial length (<18mm) was significant for higher PE.

Conclusion

Short axial length correlates with higher PE after IOL placement in infants. Less hyperopia than anticipated occurs with axial length <18 mm or high power IOLs.

Application to Clinical Practice

Quality A-scans are essential; higher PE is common, with tendency for less hyperopia than expected.

Selection of an appropriate intraocular lens (IOL) power for implantation in pediatric eyes can be difficult. Obtaining accurate and reproducible biometry measures in children, particularly infants, is challenging due to lack of patient cooperation and limitations in equipment. Technical difficulty with IOL placement during surgery may result in ciliary sulcus instead of capsular bag placement, adding additional error in achieving the target refraction. Inaccuracies in formulae for IOL power calculation for small eyes may be exaggerated in the infantile eye. Previous studies have evaluated the accuracy of formulae for use in pediatric eyes, 1–6 with Holladay and Hoffer Q giving the lowest prediction error, particularly for eyes with shorter axial length. Even when using these formulae, prediction error in pediatric eyes remains higher than that achieved in adult populations.

The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) is a multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial sponsored by the National Eye Institute undertaken to determine whether primary IOL implantation in infants between 1 and 6 months of age with unilateral cataract would result in improved visual outcomes over contact lens correction of aphakia. Half of the 114 infants enrolled in this multicenter study were randomized to receive an IOL, and then receive spectacle correction for residual refractive error. In the IATS, IOL power was chosen based on Holladay 1 calculation.

The purpose of this report is to review prediction error of refraction for infant eyes receiving primary IOL implantation in the IATS, and to look for ocular characteristics or biometry techniques that may be associated with higher error rates.

Methods

The study design, surgical techniques, patching and optical correction regimens, follow-up schedule, examination methods and baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in this study have been reported previously and therefore are only briefly summarized in this report. 7, 8 The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers, and was in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The off-label research use of the Acrysof SN60AT and MA60AC IOLs (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, Texas) was covered by US Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption # G020021.

Study Design

Infants were eligible for enrollment with a unilateral visually significant cataract (>3mm central opacity) and an age of 28 to 209 days at the time of cataract surgery. The main exclusion criteria were persistent fetal vasculature associated with stretching of ciliary processes or involvement of the optic nerve or retina, corneal diameter <9mm, premature birth (<36 weeks gestational age), presence of a medical condition that might interfere with later visual acuity testing, or acquired cataract. Patients were randomized either to have an IOL placed at the time of the initial surgery (with spectacle correction) or to be left aphakic (with contact lens correction).

Screening Exam Under Anesthesia

Prior to randomization, each infant underwent examination under anesthesia to confirm eligibility and to perform biometry of both eyes. Keratometry was performed with a hand held keratometer, with an average of at least 2 readings that varied by <1D. A-scan ultrasonography of both eyes was performed, using immersion whenever possible. Measures were taken from the scan with the best waveforms (i.e., highest peaks with a perpendicular retinal spike) using the phakic setting. If applanation A-scan ultrasonography was used, the A-scan with the greatest AC depth was used.

Surgical Technique and IOL Power Determination

Infants randomized to the IOL group had the lens aspirated followed by the implantation of an AcrySof SN60AT IOL into the capsular bag. If both haptics could not be implanted into the capsular bag, an AcrySof MA60AC IOL was implanted into the ciliary sulcus. Following IOL placement, a posterior capsulectomy and an anterior vitrectomy were performed for all eyes.

The IOL power was determined in the operating room based on A-scan ultrasonography and keratometry readings using the Holladay 1 formula. An IOL power was chosen that was closest to the power predicted to produce a +8.0 postoperative refraction for infants 4–6 weeks of age and a +6.0 D postoperative refraction for infants older than 6 weeks. If the IOL was implanted into the ciliary sulcus, then 1.0 D was subtracted from the calculated IOL power (http://www.doctor-hill.com).

Follow-up Refraction and Prediction Error

Follow-up examinations were performed 1 day, 1 week, and 1 month after surgery. Retinoscopy was performed under cycloplegia to determine residual refractive error at the one month post-operative examination. This measure was converted to spherical equivalent and compared to the predicted refraction. The predicted refraction was calculated from the Holladay 1 formula utilizing the IOL power implanted and the patient’s axial length and average keratometry reading recorded at the time of surgery. Prediction error (PE) and absolute PE were calculated as:

PE= predicted refraction - actual refraction

Absolute PE= |predicted refraction-actual refraction|

Assessment of the Quality of A-Scan Ultrasonography

All available A-scans were reviewed by a certified echographer. A-scans were graded as good quality if the gates and mode were set correctly and corneal, lens and retinal spikes were visible and of sufficient gain to be measurable, with a perpendicular leading edge for the retinal spike. It was also determined if the A-scan ultrasound was performed using a contact or immersion technique. A-scans were judged as unreadable if the quality of the print-out was sufficiently degraded such that the scan could not be adequately assessed. If an error was detected that could cause the axial length measurement to be inaccurate by >0.2mm (such as inappropriate mode, improper gate or caliper placement, or poor spike quality), then the scan was classified as poor quality.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive analyses were performed for baseline and surgery characteristics (age, axial length, average keratometry, corneal diameter, A-scan quality, IOL power, and site of IOL placement) as well as for the one-month refraction and the prediction error. Two-sample t-tests and, for non-normal factors, Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests for differences between younger patients (28–48 days old) and older patients (49–210 days old) were performed.

Bivariate associations between PE and absolute PE and the baseline and surgery characteristics were examined using the two-sample t-test for means, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for medians, and the chi-square test for percentages. Groups were compared based on age at surgery (<49 days vs. ≥49 days), keratometry measures (<46.5D vs. ≥46.5D), axial length (<18.0mm vs. ≥18.0mm), corneal diameter (<10.5mm vs. ≥10.5mm), IOL power (<30.0 D vs. ≥ 30.0 D), A-scan rating (Good quality vs. unreadable, unavailable, or poor quality), A-scan method (immersion vs. contact) and site of IOL placement (capsular bag vs. ciliary sulcus).

The relationship between PE and baseline and surgery characteristics (age category, axial length, average keratometry, corneal diameter, A-scan quality, and IOL placement) was examined using multiple linear regression; backward elimination was used to remove factors that were insignificant at the 5% level of significance. In this analysis, axial length, average keratometry, and corneal diameter were included as continuous variables.

Results

Study Patients and Baseline Characteristics

Fifty-seven of the 114 patients in the IATS were randomized to receive an IOL, and IOL implantation was completed in 56. Five patients did not have a refraction recorded at the one month visit. One patient was excluded due to incorrect recording of refraction over spectacles (instead of refraction without spectacles). Another patient was excluded because incorrect ultrasound mode with improper retinal caliper placement was used, resulting in a major error in axial length measurement and a postoperative refraction of +16.5 instead of the +8.0 D targeted. The remaining 49 eyes were included for analysis. The baseline and IOL characteristics of these 49 pseudophakic eyes are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

| Variable | Age Group | N(%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Surgery (months) | All ages | 49 | 2.5 (1.5) |

| Axial Length (mm) | All ages 28–48 Days >48 Days |

49 22 27 |

18.1 (1.4) 17.3 (0.9) 18.7 (1.4)** |

| Keratometry Reading (D) | All ages 28–48 Days >48 Days |

49 22 27 |

46.2 (2.4) 47.1 (1.8) 45.5 (2.6)* |

| Corneal Diameter (mm) | All ages 28–48 Days >48 Days |

49 22 27 |

10.5 (0.8) 10.0 (0.6) 10.9 (0.8)** |

| IOP (mmHg) | All ages 28–48 Days >48 Days |

49 22 27 |

11.5 (4.6) 10.6 (4.0) 12.3 (4.9) |

Difference between the age group means is significant at the 5% significance level

Difference between the age group means is significant at the 0.1% significance level

A-Scan Quality

Baseline A-scan ultrasound reports of the pseudophakic eye were readable for 46 of the 49 patients; one A-scan was unreadable, and two were missing. Of the 46 readable A-scans, 45 (98%) were deemed by the certified echographer to be of good quality; one A-scan for a younger patient was deemed to be of poor quality.

IOL Power and Placement

The mean IOL power implanted was 29.9 ±5.7 D overall (31.5 ± 5.0 D for the younger age group and 28.7 ± 6.0 D for the older age group); IOL power range was 11.5 D to 40.0 D. Twenty-five eyes were implanted with an IOL power ≥ 30.0 D, and 10 of these were implanted with an IOL power ≥35.0 D.

Forty-six patients (94%) had IOL placement within the capsular bag. Ciliary sulcus IOL placement was performed for one patient in the younger age group and 2 patients in the older age group.

Follow-up Refraction and Prediction Error

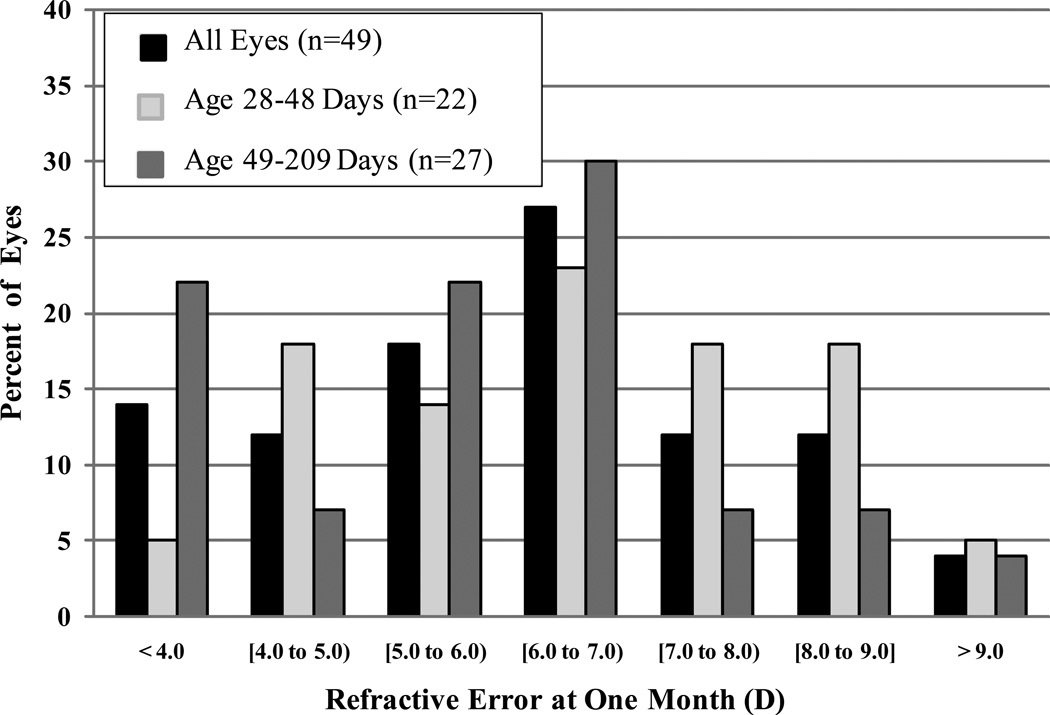

The overall mean refraction at one month was +6.1 ±2.0 D; the distribution of refractions is shown in Figure 1. The mean refraction was +6.6 ±1.9 D in the younger age group and +5.7 ±2.0 D in the older age group. Twenty-two eyes (45%) achieved a postoperative refraction within 1.0 D of the target refraction of +8.0 D or +6.0 D outlined by the IATS protocol. There were 7 eyes (14%) in which the surgeon implanted an IOL predicted to give a postoperative refraction that varied from the IATS protocol by >1 D, but the actual refraction was still within 1.0 D of the IATS target for 3 of these eyes. One eye had the highest power IOL available implanted (40.0 D), which was predicted to result in a refraction of +9.5 D instead of the target of +8.0 D, but the actual postoperative refraction was +6.5 D.

Figure 1.

Distribution of refractive error (D) at one month, overall and stratified by age group (28–48 days vs. 49–209 days). The overall mean refractive error was 6.1 ±2.0 D. The mean was 6.6 ±1.9 D in the younger age group and 5.7 ±1.9 D in the older age group.

The prediction error (PE) and absolute PE are reported in Table 2. The actual refractions at the one month visit showed less residual hyperopia than predicted, with an overall mean PE of +1.0 ±2.0 D. Differences in mean PE were seen based on age at surgery, and differences were seen in both mean PE and mean absolute PE based on baseline globe axial length, baseline corneal diameter, and IOL power implanted. However, in multiple linear regression analyses, only globe axial length was significant.

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations Between Prediction Error (D) and Baseline and Surgery Characteristics

| PE | Absolute PE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Group | n | Mean(SD) | P-value1 | Mean(SD) | P-value1 |

| Prediction Error | 49 | 1.0 (2.0) | - | 1.8 (1.3) | - | |

| Age at Surgery | 28–48 Days >48 Days |

22 27 |

1.6 (2.0) 0.5 (1.9) |

0.047 |

2.0 (1.6) 1.6 (1.1) |

0.32 |

| Axial Length (mm) | <18.0mm ≥18.0mm |

27 22 |

1.8 (2.0) −0.1 (1.6) |

<0.001 |

2.2 (1.5) 1.3 (1.0) |

0.01 |

| Keratometry Reading (D) |

<46.50D ≥46.50D |

26 23 |

1.0 (2.1) 0.9 (2.0) |

0.82 |

1.8 (1.4) 1.8 (1.3) |

0.90 |

| Corneal Diameter (mm) |

<10.5 ≥10.5 |

21 28 |

1.8 (2.0) 0.3 (1.8) |

0.01 |

2.3 (1.5) 1.5 (1.1) |

0.04 |

| A-Scan Rating | Good Quality Other |

45 4 |

1.1 (2.0) −0.7 (2.1) |

0.10 |

1.8 (1.4) 1.8 (0.9) |

0.99 |

| A-Scan Method | Immersion Contact |

32 14 |

1.0 (2.0) 0.9 (2.0) |

0.90 |

1.7 (1.3) 1.8 (1.3) |

0.91 |

| IOL Power (D) | <30.0 D ≥30.0 D |

24 25 |

−0.3 (1.6) 2.2 (1.7) |

<0.001 |

1.3 (1.0) 2.3 (1.5) |

0.004 |

| IOL Placement | Capsular Bag Sulcus |

46 3 |

1.1 (2.0) −0.6 (3.0) |

0.34 |

1.8 (1.3) 2.1 (1.7 |

0.89 |

P-values are for two-sample t-tests, except for baseline A-scan rating and IOL placement (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Poor quality, unreadable or missing A-scans

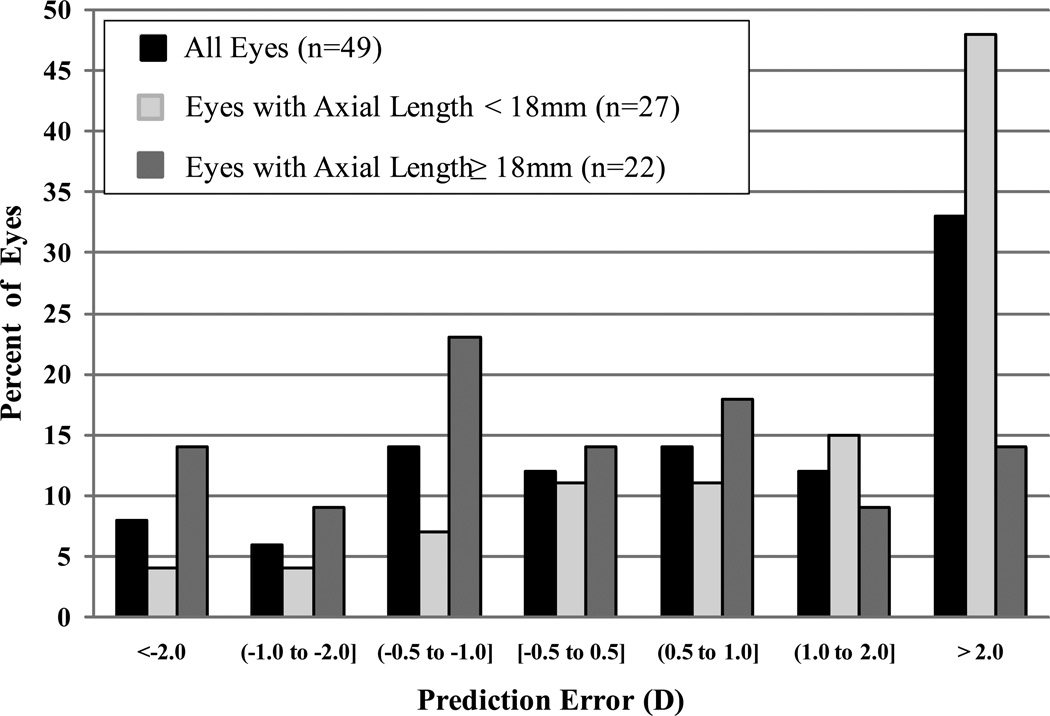

Figure 2 shows the distribution of prediction errors. Only 6 (12%) of the 49 eyes had absolute PE less than 0.5 D, 20 (41%) had absolute PE less than 1.0 D, and 29 (59%) had absolute PE <2.0D (Figure 2). Of the 20 eyes with absolute PE >2.0 D, 14 (70%) had axial lengths less than 18mm, compared with 13 (45%) of 29 eyes with absolute PE ≤ 2.0D (p-value =0.08; 95% confidence interval for difference in percentages, PE > 2.0D minus PE ≤ 2.0D, −3% to 54%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of prediction error (D), overall and stratified by axial length (<18mm vs. ≥18mm).

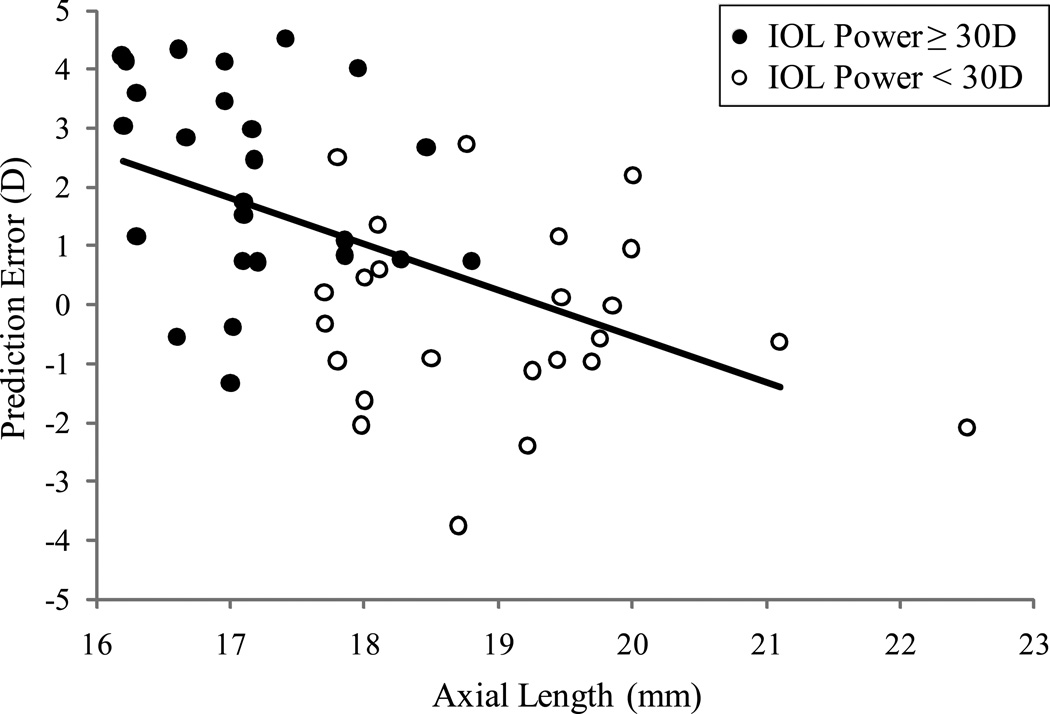

Prediction error in relation to axial length is shown in Figure 3. A negative trend for prediction error was seen with increasing axial length (linear regression coefficient −0.8, standard error 0.2, R-square 0.3, p-value < 0.0001), that is, an increase in axial length of 1 mm was associated with a 0.8 D decrease in mean PE in this cohort. When IOL power >30D was implanted, 88% had less residual hyperopia when refracted at one month after surgery than intended. Of the 20 eyes with absolute PE >2.0 D, 13 were implanted with IOL power ≥30.0 D and all had less hyperopia than intended, compared to 4 of 7 (57%) with less hyperopia than intended when IOL <30.0 D was implanted (p-value=0.03).

Figure 3.

Prediction error (PE) in relation to axial length and IOL power. The solid line represents the estimated simple linear regression model relating PE to axial length (regression coefficient −0.8, standard error 0.2, R-square 0.3, p-value < 0.0001).

Discussion

Infants in the IATS underwent surgery using standardized techniques and IOL selection criteria, using the Holladay 1 formula for a specified postoperative refractive target. At the one month post-operative visit, only 41% of eyes were within 1D of the refractive target, and PE >2D was seen in another 41% of eyes. Higher PE in IOL calculation is not surprising in this population of infantile eyes, where extremely short axial length and steep keratometry measures are common. In a multivariable analysis, axial length was the only factor found to be independently associated with PE, with shorter eyes having greater PE. Additionally, of the 20 eyes with absolute PE >2D, most (80%) were overcorrected, leaving less residual hyperopia than expected.

Errors in IOL calculation often come from measurement error during biometry, instrumentation error, or formula error. 9, 10 Improper A-scan ultrasound technique was used in one patient, resulting in a large error in globe axial length assessment. This eye was excluded from the overall analysis, since such an error would outweigh any eye or surgery characteristics that could impact postoperative refraction targeting. Since keratometry and A-scans are usually performed under anesthesia for infants, lack of fixation may also induce measurement error. Instruments are calibrated for adult eyes, and the proportional differences in the infant globe may cause errors in measurement. Ultrasound uses an average velocity of 1550m/s, but the infant eye with a proportionally larger lens would have a faster velocity. We did not find a significant difference in mean PE based on method of ultrasound, though there is concern that contact biometry may underestimate axial length due to compression forces. 11, 12,13 However, others have shown no significant difference in axial length measurements using contact vs. immersion ultrasound methods, 14 including a pediatric series comparing PE in eyes that had immersion vs. contact ultrasound measurements under general anesthesia. 15 Axial length measurement errors in children have been shown to result in larger errors in IOL power selection, such that a 4 to 14D/mm error in axial length may occur in pediatric eyes compared with 3 to 4D/mm error in axial length in adults. 9 The IOL power calculation difference with keratometry error of 0.8 to 1.3 D/D was noted to be similar between children and adults. 9

Formulaic errors may occur based on assumptions about IOL position within the eye, anterior chamber depth, and are magnified with placement of higher powered IOLs. 16 Half of the eyes in this cohort had IOL power >30.0 D. While a higher mean PE was demonstrated with IOL power >30.0 D, and even higher for the 10 eyes that received an IOL power ≥ 35.0 D, these were typically implanted in shorter eyes, so analyses of the effect of IOL power on PE are confounded by axial length.

The IATS used the Holladay 1 formula for IOL calculation. In adult populations, the Holladay, Hoffer Q, and Haigis formulae have all been used for eyes with axial length <22mm. 17–19 Pediatric studies have failed to show a significant difference in mean absolute PE amongst formulae overall, 2, 5 and in a mathematical analysis of IOL power prediction in the pediatric range of keratometry and axial length values, it appears unclear which formula may give the best prediction for an individual patient. 20

Postoperative refraction was determined by retinoscopy. The inability of an infant to cooperate may lead to off-axis retinoscopy or variations in the vertex distance during retinoscopy. Errors are also magnified with high refractive errors. Eye growth occurs rapidly in the first 6 months of life, so that increases in axial length during the first month after surgery could result in a reduction in the amount of hyperopia measured. Based on a hybrid logarithmic model of typical refractive growth, 21 a typical eye made pseudophakic at age 1 month with a postoperative refraction of +8.0 D will have a myopic shift of 0.7 D by the age of 2 months, and a typical eye made pseudophakic at age 5 month with a postoperative refraction of +6.0 D will have a myopic shift of 0.4 D by the age of 6 months. Refraction was deferred until the one month visit to allow for resolution of the potentially large astigmatic error that can be induced by sutures in infant eyes, or changes induced by inflammation or corneal edema.

The overall mean absolute PE was 1.8 D ±1.3 D. Previous reports show mean absolute PE ranging from 0.7 D to 1.5D for pediatric eyes undergoing primary IOL implantation. 1–6, 13, 15, 22 Mean absolute PE is often higher and less predictable for eyes <22mm, even when using formulae designed for short eyes, 1, 4, 5 and in this cohort, 48 of 49 eyes had axial length <22mm. Most eyes with absolute PE >2 D in this cohort had axial length <18mm. Since axial length measurements >20mm were uncommon in this population (only 4 eyes), axial length measurements that are substantially longer than this should be carefully reviewed for accuracy.

Mean PE was calculated to assess the direction of miscalculation, with an undercorrection (more residual hyperopia than expected) represented by a negative value and an overcorrection (less residual hyperopia than expected) represented by a positive value. The mean PE for eyes >18mm was −0.1 ±1.6 D, reflecting an almost equal number of overcorrections and undercorrections postoperatively, but eyes <18mm were often overcorrected, with less residual hyperopia than anticipated. Similarly, when eyes were compared by age group at surgery, less overcorrection was seen in the older group compared to the younger group. However, this may be explained by the expectation of more rapid ocular growth in the shorter, younger eyes in the early postoperative period. Elevated intraocular pressure can cause axial elongation and myopic shift in the infant eye, though none of the eyes were diagnosed with glaucoma by the one month visit.

Gale et al 23 has suggested that after uncomplicated adult cataract surgery, 55% of eyes should have prediction error of ± 0.5 D, and 85% should have PE ±1.00 D. In pediatric populations, however, the number of patients with PE ±1.0 D is lower. In one series, 43% of pediatric eyes had PE ±0.5D and 74.5% had PE ±1.0 D using Holladay 1, but in the subset of eyes <22mm only 20% had PE ±0.5D and 45% had PE ±1.0 D 5. Not surprisingly, in the IATS a similarly low percentage of infants achieved PE ±0.5 D (12%) or ±1.0 D (41%).

In conclusion, a relatively large PE is common when performing IOL implantation in infant eyes, especially with the shortest axial lengths (<18mm), even when using a formula designed for short eyes. Additionally, implantation of IOL power ≥30.0 D usually resulted in less residual hyperopia than expected. In these growing eyes, with less baseline hyperopia than planned and expected axial elongation, significant myopia may result in the long term. Refractive status of these children as they become older will be the subject of a future report.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Cynthia Kendall reviewed and graded the quality of all of the A-scan ultrasound reports for the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

Michael Lynn had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

*Appendix 1

The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group

Administrative Units and Participating Clinical Centers

Clinical Coordinating Center (Emory University): Scott R. Lambert, M.D. (Study Chair), Lindreth DuBois MEd, MMSc (National Coordinator)

Data Coordinating Center (Emory University): Michael Lynn MS (Director), Betsy Bridgman BS, Marianne Celano PhD, Julia Cleveland MSPH, George Cotsonis MS, Carey Drews-Botsch PhD, Nana Freret MSN, Lu Lu MS, Azhar Nizam MS, Seegar Swanson, Thandeka Tutu-Gxashe MPH

Visual Acuity Testing Center (University of Alabama, Birmingham): E. Eugenie Hartmann PhD (Director), Clara Edwards, Claudio Busettini PhD, Samuel Hayley

Steering Committee: Scott R Lambert MD, Edward G. Buckley MD, David A. Plager MD, M. Edward Wilson MD, Michael Lynn MS, Lindreth DuBois Med MMSc, Carolyn Drews-Botsch PhD, E. Eugenie Hartmann PhD, Donald F Everett MA

Contact Lens Committee: Buddy Russell COMT, Michael Ward MMSc

Participating Clinical Centers (In order by the number of patients enrolled):

Medical University of South Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina (14): M. Edward Wilson MD, Margaret Bozic CCRC, COA

Harvard University; Boston, Massachusetts (14): Deborah K. VanderVeen MD, Theresa A Mansfield RN, Kathryn Bisceglia Miller OD

University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, Minnesota (13): Stephen P. Christiansen MD, Erick D. Bothun MD, Ann Holleschau, Jason Jedlicka OD, Patricia Winters OD, Jacob Lang OD

Cleveland Clinic; Cleveland, Ohio (10): Elias I. Traboulsi MD, Susan Crowe BS, COT, Heather Hasley Cimino OD

Baylor College of Medicine; Houston, Texas (10): Kimberly G Yen MD, Maria Castanes MPH, Alma Sanchez COA, Shirley York

Oregon Health and Science University; Portland, Oregon (9): David T Wheeler MD, Ann U. Stout MD, Paula Rauch OT, CRC, Kimberly Beaudet CO, COMT, Pam Berg CO, COMT

Emory University; Atlanta, Georgia (9): Scott R. Lambert MD, Amy K. Hutchinson MD, Lindreth DuBois Med, MMSc, Rachel Robb MMSc, Marla J. Shainberg CO

Duke University; Durham, North Carolina (8): Edward G. Buckley MD, Sharon F. Freedman MD, Lois Duncan BS, B.W. Phillips, FCLSA, John T. Petrowski, OD

Vanderbilt University: Nashville, Tennessee (8): David Morrison MD, Sandy Owings COA, CCRP, Ron Biernacki CO, COMT, Christine Franklin COT

Indiana University (7): David A Plager MD, Daniel E. Neely MD, Michele Whitaker COT, Donna Bates COA, Dana Donaldson OD

Miami Children’s Hospital (6): Stacey Kruger MD, Charlotte Tibi CO, Susan Vega

University of Texas Southwestern; Dallas, Texas (6): David R. Weakley MD, David R. Stager, Jr., Joost Felius PhD, Clare Dias CO, Debra L. Sager, Todd Brantley OD

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Robert Hardy PHD (Chair), Eileen Birch PhD, Ken Cheng MD, Richard Hertle MD, Craig Kollman PhD, Marshalyn Yeargin-Allsopp MD, (resigned), Cyd McDowell, Donald F. Everett MA

Medical Safety Monitor: Allen Beck MD

Footnotes

Members and affiliations of the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group are listed in Appendix A

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreo LK, Wilson ME, Saunders RA. Predictive value of regression and theoretical IOL formulas in pediatric intraocular lens implantation. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1997 Jul-Aug;34(4):240–243. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19970701-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mezer E, Rootman DS, Abdolell M, Levin AV. Early postoperative refractive outcomes of pediatric intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004 Mar;30(3):603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore DB, Ben Zion I, Neely DE, et al. Accuracy of biometry in pediatric cataract extraction with primary intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008 Nov;34(11):1940–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neely DE, Plager DA, Borger SM, Golub RL. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculations in infants and children undergoing cataract surgery. J AAPOS. 2005 Apr;9(2):160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nihalani BR, VanderVeen DK. Comparison of intraocular lens power calculation formulae in pediatric eyes. Ophthalmology. 2010 Aug;117(8):1493–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tromans C, Haigh PM, Biswas S, Lloyd IC. Accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation in paediatric cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001 Aug;85(8):939–941. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.8.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch C, et al. The infant aphakia treatment study: design and clinical measures at enrollment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan;128(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch C, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing contact lens with intraocular lens correction of monocular aphakia during infancy: grating acuity and adverse events at age 1 year. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jul;128(7):810–818. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eibschitz-Tsimhoni M, Tsimhoni O, Archer SM, Del Monte MA. Effect of axial length and keratometry measurement error on intraocular lens implant power prediction formulas in pediatric patients. J AAPOS. 2008 Apr;12(2):173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norrby S. Sources of error in intraocular lens power calculation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008 Mar;34(3):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen T, Nielsen PJ. Immersion versus contact technique in the measurement of axial length by ultrasound. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1989 Feb;67(1):101–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schelenz J, Kammann J. Comparison of contact and immersion techniques for axial length measurement and implant power calculation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1989 Jul;15(4):425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(89)80062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trivedi RH, Wilson ME. Prediction error after pediatric cataract surgery with intraocular lens implantation: Contact versus immersion A-scan biometry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011 Mar;37(3):501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennessy MP, Franzco, Chan DG. Contact versus immersion biometry of axial length before cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003 Nov;29(11):2195–2198. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Zion I, Neely DE, Plager DA, Ofner S, Sprunger DT, Roberts GJ. Accuracy of IOL calculations in children: a comparison of immersion versus contact A-scan biometery. J AAPOS. 2008 Oct;12(5):440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClatchey SK, Hofmeister EM. The optics of aphakic and pseudophakic eyes in childhood. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar 4;55(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffer KJ. The Hoffer Q formula: a comparison of theoretic and regression formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993 Nov;19(6):700–712. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holladay JT. Standardizing constants for ultrasonic biometry, keratometry, and intraocular lens power calculations. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997 Nov;23(9):1356–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacLaren RE, Natkunarajah M, Riaz Y, Bourne RR, Restori M, Allan BD. Biometry and formula accuracy with intraocular lenses used for cataract surgery in extreme hyperopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;143(6):920–931. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eibschitz-Tsimhoni M, Tsimhoni O, Archer SM, Del Monte MA. Discrepancies between intraocular lens implant power prediction formulas in pediatric patients. Ophthalmology. 2007 Feb;114(2):383–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boisvert C, Beverly DT, McClatchey SK. Theoretical strategy for choosing piggyback intraocular lens powers in young children. J AAPOS. 2009 Dec;13(6):555–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchinson AK, Wilson ME, Saunders RA. Outcomes and ocular growth rates after intraocular lens implantation in the first 2 years of life. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998 Jun;24(6):846–852. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(98)80142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gale RP, Saldana M, Johnston RL, Zuberbuhler B, McKibbin M. Benchmark standards for refractive outcomes after NHS cataract surgery. Eye (Lond) 2009 Jan;23(1):149–152. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]