Dear Editor: The availability of cell lines that are both reflective of the tumor of origin and well characterized is critical for advancing melanoma research. While a wealth of melanoma cell lines exists, the majority have been subject to frequent and prolonged passaging, leaving them vulnerable to accumulation of genetic abnormalities. As such, many existing melanoma cell lines no longer contain the original tumor's genetic profile, metastatic potential and pigmentation characteristics (Kameyama et al., 1990; Schadendorf et al., 1996), thus compromising their ability to predict in vivo clinical activity when used for in vitro testing (Salgia and Skarin, 1998). Additionally, many of these cell lines lack clinical annotation, including patient demographics, tumor localization, characteristics of the primary tumor and pre-culture therapeutic intervention that could provide important clinical context. Here, we describe the development of 5 novel metastatic melanoma low passage cell lines (LPCLs), with extensive clinical and phenotypic characterization that proved to be representative of the originating tumors. These cell lines could be used to enrich and add diversity to existing cell line panels for preclinical testing or used for hypothesis development and proof-of-principle experiments.

Fresh melanoma specimens collected from skin, lymph node, and brain metastatic tissues of patients enrolled in New York University's Interdisciplinary Melanoma Cooperative Group (NYU IMCG) database (Wich et al., 2009) were used for cell isolation and culture (Appendix S1). Purity of LPCLs was confirmed with immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) using melanoma markers Melan A, HMB45 and S100. Subpopulations of possible tumorigenic melanoma cells were identified and/or confirmed using a combination of IHC, qRT-PCR and flow cytometry for putative tumorigenic markers and in vivo tumorigencicity of two LPCLs was tested. DNA and RNA was extracted from LPCLs and corresponding tissues and used to assess status of BRAF, NRAS, CDKN2A and KIT genes. Karyotypes were evaluated for gross chromosomal aberrations using G-banding analysis (Appendix S1).

Patients' clinicopathological information at the time of metastatic tissue acquisition and the basic characteristics of the LPCLs, including tumor source and passage number at which stable LPCLs were established, are listed in Table 1. As with all patients enrolled in the NYU IMCG, prospectively collected clinical information in 371 fields is available for the newly developed LPCLs, including detailed information about the primary tumor (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at tissue acquisition of low passage cell lines

| LPCL ID | Gender | Age | Pathologic Stage* | Tumor Site | Treatment History** | Passage # Characterized | Growth Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NYU08-175 | Male | 83 | IIIB | Regional Skin | Adjuvant Radiation, temozolomide | 10 | Adherent |

| NYU09-085 | Female | 68 | IV | Brain Metastasis | Adjuvant Interferon-alphaand NY-ES0 vaccine, carboplatin/MK-1775, Gamma Knife | 14 | Majority adherent, stem cell like clusters |

| NYU09-203 | Male | 74 | IIIC | Regional LN | None | 12 | Majority floating |

| NYU10-040 | Male | 78 | IIIB | Regional LN | None | 10 | Adherent |

| NYU10-230 | Male | 27 | IIIC | Regional LN | None | 10 | Adherent |

2009 AJCC Staging;

Treatment history prior to resection of tumor of origin for the LPCLs

Key: LPCL: Low passage cell line;

LN: Lymph Node;

MK-1775: Wee-1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor

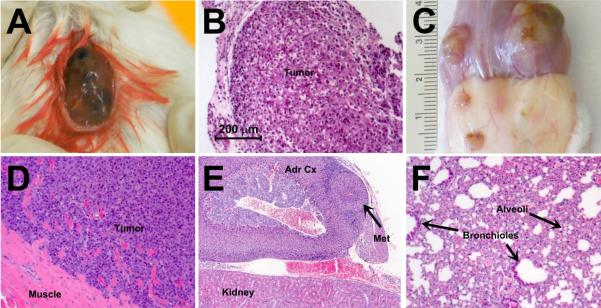

As presented in Table 2, IHC confirmed purity of LPCLs as melanoma via homogneous staining of melanoma markers and demonstrated variable sub-populations within each LPCL expressing nestin, CD133, CD166, and ABCB5, reported tumorigenic melanoma markers (Wiese et al., 2004, Supplemental Figure S1). qRT-PCR and flow cytometry both independently verified the expression of CD133 and ABCB5 detected by IHC, although variability in expression detected by different modalities was noted in 2 cell lines (NYU-09-085 and NYU-09-203). Additionally, qRT-PCR also verified expression of CD166 and demonstrated very strong expression of CD271 and JARID1B by all LPCLs. The two tested LPCLs (NYU08-175 and NYU09-203) demonstrated in vivo tumorigenicity. NYU08-175 produced large pigmented tumors at the injection site after 12 weeks and NYU09-203 produced highly invasive tumors at 3 weeks and visceral metastases at 6 weeks (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical phenotypes of low passage cell lines

| LPCL ID | Melanoma Markers |

Tumorigenic Melanoma Cell Markers |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-100 | Melan A | HMB45 | Nestin | CD133 | ABCB5 | CD166 | |

| NYU08-175 | + | + | + | strong | strong | strong | moderate |

| NYU09-085 | + | + | + | weak | moderate | moderate | negative |

| NYU09-203 | + | + | + | strong | strong | strong | moderate |

| NYU10-040 | + | + | + | moderate | weak | weak | negative |

| NYU10-230 | + | + | + | moderate | moderate | weak | moderate |

Key: LPCL: Low passage cell line

Figure 1.

In vivo tumorigenecity of LPCLs NYU-08-175 and NYU-09-203. A) Gross appearance of encapsulated, pigmented primary tumor produced by subcutaneous injection of NYU-08-175 cells, resembling the appearance of the original tumor. B) H&E of the primary tumor. C) Gross appearance of primary tumor produced by subcutaneous injection of NYU-09-203 cells, showing attachment to muscle and skin. D) H&E of the primary tumor, demonstrating invasion of the tumor into the muscle. E) H&E of an adrenal cortex metastasis. Metastases were present in both adrenal cortices. F) H&E of lung metastasis demonstrating the loss of the alveolar space and the replacement on the lung parenchyma by the metastasis.

Mutational analysis revealed a heterogeneous group of cell lines and confirmed that these newly established LPCLs contain the same mutations as the tumor of origin and have not undergone in vitro transformations in the genes examined. Specifically, two LPCL and corresponding tissue pairs harbored the common NRAS Q61K mutation in exon 2 (NYU09-085, NYU10-230), one LPCL/tissue pair expressed a BRAF V600E mutation in exon 15 (NYU09-203), one LPCL/tissue pair (NYU08-175) had a single nucleotide substitution (AGgt to AGat) in a highly conserved region of the 3' donor splice junction of the exon 2-intron 2 boundary of CDKN2a, which will disrupt production of either transcript of the gene (Loo et al., 2003; Rutter et al., 2003), and the last LPCL/tissue pair (NYU10-040) harbored 2 SNPs in the coding region of KIT (homozygous for ATG–CTG L541M as show by CTG-CTC/G L862L). Sequencing results of the molecular characterization for the LPCLs and the tumors of origin are summarized in Supplemental Figure S2.

Malignant melanomas typically exhibit complex karyotypes with numerous structural and numerical aberrations and a high degree of aneuploidy (Hoglund et al., 2004). Consistent with published reports, highly complex chromosomal aberrations were seen in each of our LPCLs, including gains of 1q and losses of 6q, commonly described recurrent anomalies in melanoma (Albino et al., 1992, Supplemental Figure S3). Due to the complexity of the karyotypes, only partial characterization by G-banding analysis was possible. However, as cytogenetic analysis of melanoma has been reported on established cell lines, demonstrating that the chromosome data provide a proper assay for identification (Becher et al., 1983), we were able to verify the development of 5 individual unrelated cell lines, each with its own unique karyotype (Supplemental Figure S3).

Though we only describe a small set of melanoma cell lines, they have the potential to be a new, invaluable resource for the melanoma community. Specifically, we introduce newly established cell lines that have yet to be subject to prolonged passaging and confirm their close genotypic resemblance to the tissues of origin. Moreover, each LPCL demonstrates unique subpopulations of potential tumorigenic melanoma cells and can fuel studies seeking to more clearly elucidate the role these cells have in disease progression, dissemination and recurrence. Lastly, the extensive clinicopathological annotation of each line, a feature often lacking in existing available lines, makes these lines a unique tool for melanoma preclinical testing and translational research.

Supplementary Material

References

- Becher R, Gibas Z, Karakousis C, Sandberg AA. Nonrandom chromosome changes in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 1983;43:5010–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund M, Gisselsson D, Hansen GB, White VA, Sall T, Mitelman F, Horsman D. Dissecting karyotypic patterns in malignant melanomas: temporal clustering of losses and gains in melanoma karyotypic evolution. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2004;108:57–65. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama K, Vieira WD, Tsukamoto K, Law LW, Hearing VJ. Differentiation and the tumorigenic and metastatic phenotype of murine melanoma cells. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 1990;45:1151–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo JC, Liu L, Hao A, Gao L, Agatep R, Shennan M, Summers A, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Deters C, et al. Germline splicing mutations of CDKN2A predispose to melanoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:6387–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter JL, Goldstein AM, Davila MR, Tucker MA, Struewing JP. CDKN2A point mutations D153spl(c.457G > T) and IVS2+1G > T result in aberrant splice products affecting both p16(INK4a) and p14(ARF) Oncogene. 2003;22:4444–4448. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgia R, Skarin AT. Molecular abnormalities in lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:1207–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadendorf D, Fichtner I, Makki A, Alijagic S, Kupper M, Mrowietz U, Henz BM. Metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice--characterisation of phenotype, cytokine secretion and tumour-associated antigens. British journal of cancer. 1996;74:194–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wich LG, Hamilton HK, Shapiro RL, Pavlick A, Berman RS, Polsky D, Goldberg JD, Hernando E, Manga P, Krogsgaard M, et al. Developing a multidisciplinary prospective melanoma biospecimen repository to advance translational research. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1:35–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese C, Rolletschek A, Kania G, Blyszczuk P, Tarasov KV, Tarasova Y, Wersto RP, Boheler KR, Wobus AM. Nestin expression--a property of multi-lineage progenitor cells? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2510–22. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albino AP, Sozzi G, Nanus DM, Jhanwar SC, Houghton AN. Malignant transformation of human melanocytes: induction of a complete melanoma phenotype and genotype. Oncogene. 1992;7:2315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.