Abstract

Delay discounting describes the devaluation of a reinforcer as a function of the delay until its receipt. Although all people discount delayed reinforcers, one consistent finding is that substance-dependent individuals tend to discount delayed reinforcers more rapidly than do healthy controls. Moreover, these higher-than-normal discounting rates have been observed in individuals with other behavioral maladies such as pathological gambling, poor health behavior, and overeating. This suggests that high rates of delay discounting may be a trans-disease process (i.e., a process that occurs across a range of disorders, making findings from one disorder relevant to other disorders). In this paper, we argue that delay discounting is a trans-disease process, undergirded by an imbalance between two competing neurobehavioral decision systems. Implications for our understanding of, and treatment for, this trans-disease process are discussed.

Keywords: Delay discounting, trans-disease process, neuroscience, addiction, gambling, obesity, health behaviors

Introduction

Imagine that you cannot wait to engage in an activity, and you do so as often as you can. This behavior, however, causes you and others great sadness and suffering. You want to stop engaging in this behavior, yet you engage in this behavior as often as possible. This scenario is frequently evident among those who are addicted to drugs. Our view is that the choices of the addicted reflect an undervaluation of the longer-term consequences of their behavior, resulting in a limited ability to follow through with plans. Substantial and growing evidence suggests that this undervaluation may be related to the extensively studied behavioral process known as the discounting of delayed reinforcers. Discounting refers to the observed tendency for the value of reinforcers to decrease as a function of the delay to their delivery (Rachlin & Green, 1972). The systematic measure of this effect, also called “delay discounting,” is often considered a measure of impulsivity (Bickel & Marsch, 2001).

As we will show in this review, drug-dependent individuals discount delayed reinforcers substantially more rapidly than individuals who do not use drugs. These excessive rates of delay discounting are not exclusive to drug dependence, but rather seem to relate to a broader set of disorders. Indeed, as we will address below, excessively high rates of delay discounting are characteristic of individuals with gambling problems, the obese, those who engage in unhealthy actions such as risky sexual behavior, and individuals diagnosed with ADHD or schizophrenia. From our perspective, this evidence of excessive discounting across these differing disorders and disease-related vulnerabilities suggests that excessive discounting should be considered a trans-disease process.

Viewing the excessive discounting of future outcomes as a trans-disease process differs from the traditional and contemporary approach to disease (see Bickel & Mueller, 2009 for a more indepth treatment of the contemporary analysis of disease). Briefly, the contemporary analysis of disease suggests that each disease has its own etiology. This approach is reflected in the variety of scientific organizations focused on particular diseases, and in the United States by the various institutes of the National Institutes of Health. The presumption of distinctive etiologies for each disease combines with the need for increasingly specialized research training of scientists to promote a reductionist approach to science, which assumes that a greater understanding of the disease process will be evident in an ever-smaller part of the phenomena under study. Furthermore, to remain fully informed about current developments in a given specialty area, scientists must read and process an ever-increasing number of publications. A consequence is that successful modern disease scientists need to know more and more about less and less. The end result is scientific silos, with failures to recognize characteristics common across different diseases, or across behavioral precursors of various diseases. In other words, researchers working on one disease may be either unaware of relevant observations and experiments of those working on other diseases, or unable to translate relevant observations and methodologies from the study of other diseases into theory and procedures that may advance understanding in their area.

By contrast to the scenario derived from distinct disease etiologies, the notion of trans-disease process suggests that there are processes common across diseases. As a result, the science from one disease can profit from learning about processes in, or precursors of, other diseases. This knowledge of trans-disease processes may drive our understanding of diseases forward – both individually and collectively (see Bickel & Mueller, 2009). Moreover, there may be other trans-disease processes, in addition to excessive discounting, such as those associated with stress (Sapolsky, 2005) or autoimmune response (Rose & Bona, 1993).

In this paper, we will consider humans’ excessive discounting of future events a trans-disease process underlying addiction, other disorders, and disease-related behaviors. We will then consider the systematic processes that underlie the discounting of delayed reinforcers, and the dimensional model of addiction that these underlying processes suggest. And lastly, we will consider the implications of this knowledge about excessive discounting for disease therapy.

Research on the Discounting of Delayed Reinforcers

All other things being equal, nearly anyone would prefer to receive a reinforcer (e.g., $1,000) now rather than later. This suggests that delayed reinforcers are valued less, or “discounted.” Most individuals, however, do not discount reinforcers at a linearly constant rate. For example, although a reinforcer delivered a year from now may lose half of its subjective value, that same reinforcer would not be worthless (i.e., lose the other half of its subjective value) two years from now. This observation has led to the development of sophisticated procedures to measure and quantify this effect.

Delay discounting procedures

The measurement of delay discounting

Delay discounting is often measured using procedures borrowed from psychophysics (e.g., titrating the difference in intensity of two tones based on a subject’s responses, to determine the lowest perceivable difference). For example, Du et al. (2002) used a procedure wherein subjects chose between immediate and delayed reinforcers (i.e., amounts of money) that were presented on a computer screen. Across a series of trials, the magnitude of a reinforcer (e.g., $1,000) delayed by a specified amount of time (e.g., one year from now) remained constant whereas the magnitude of an immediate reinforcer began at one half of the magnitude of the delayed reinforcer (e.g., $500) and increased by 50% with each selection of the delayed reinforcer and decreased by 50% with each selection of the immediate reinforcer. Using this titration procedure, the investigators were able to determine the amount of an immediate reinforcer (e.g., $100 now) that was subjectively equivalent to the amount of the larger delayed reinforcer (e.g., $1,000 one year from now). When repeated across multiple delay parameters (e.g., one day, one week, one month, six months, one year, five years, and twenty-five years) these titration-determined values, referred to as indifference points, can describe a function that specifies the rate at which individuals discount delayed reinforcers (cf. Kirby et al., 1999; Reynolds & Schiffbauer, 2004).

Due to practical or ethical concerns (e.g., the study of illicit drugs as reinforcers, large monetary values of reinforcers, etc.), delay-discounting tasks often ask participants to choose between hypothetical reinforcers. In order for these results to have scientific validity, however, participants must choose hypothetical reinforcers as if the reinforcers are real. Fortunately, numerous studies have examined the relation between discounting of real and hypothetical reinforcers (Baker et al., 2003; Bickel et al., 2009b; Johnson & Bickel, 2002; Johnson et al., 2007; Madden et al., 2003; 2004). In all cases, patterns of discounting were similar for real and hypothetical reinforcers. Moreover, discounting rates determined via hypothetical assessment procedures predict actual monetary behavior (Bickel et al., 2010). This empirically demonstrated consistency strengthens the inferences that can be made based on the discounting of hypothetical reinforcers.

The quantification of discounting rate

With the excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers co-occurring across so many disorders and patterns of maladaptive behavior (see below), the quantification of discounting rate has generated much interest (e.g., Green & Myerson, 2004; Kable & Glimcher, 2010; Killeen, 2009; Mazur, 1987; McKerchar et al., 2009; Rachlin, 2006). Although those working in the framework of standard economic theory posit that delayed reinforcers are exponentially discounted, considerable data suggest that the hyperbolic functions favored in behavioral economics (Mazur, 1987) better describe existing data (Bickel et al., 1999; Green et al., 1996).

These hyperbolic functions (Mazur, 1987) are typically fit using the equation

which describes how the value (V) of a given amount (A) of a delayed (D) reinforcer is discounted at a given rate (k). The value of this free parameter has frequently been used as a marker of within-subject (e.g., between commodities) and between-group (e.g., drug users versus non-using controls) differences.

Although rates of discounting are generally consistent over periods up to one year (Baker et al., 2003; Beck & Triplett, 2009; Black & Rosen, 2011; Ohmura et al., 2006; Simpson & Vuchinich, 2000; Takahashi et al., 2007) individuals’ choices between alternatives may differ across time points. For example, on Friday morning one may express intent to go to the gym rather than the bar after work, yet preference between these activities may shift as happy hour approaches. Unlike the exponential discounting functions favored by standard economic theory, the hyperbolic functions used in behavioral economics can account for these types of preference reversals (Green & Estle, 2003; Monterosso & Ainslie, 2007).

Figure 1 illustrates this phenomenon. Specifically, Figure 1 shows the value of a given reinforcer (Y-axis) as a function of the time until its delivery (X-axis) as predicted by exponential (left panel) and hyperbolic (right panel) discounting models. Exponential models (left panel) predict that reinforcer value decreases by a constant proportion of the reinforcer’s remaining value across all delays. As a result, the value of the smaller yet more immediate reinforcer (the shorter, leftmost vertical line) is always less than that of the larger yet delayed reinforcer (i.e., the taller vertical line). Because choice typically reflects the current value of two alternatives, exponential models predict that one reinforcer would be consistently chosen over the other, determined solely by their relative value and the duration of time between their availability, and independent of when the choice is made (i.e., no preference reversal). By contrast, hyperbolic discounting models (right panel), predict initially rapid reinforcer devaluation followed by a more gradual decrease in reinforcer value. Because the devaluation rate is not a constant proportion of remaining value in a hyperbolic model, the larger but more delayed reinforcer (taller, rightmost vertical line in the right panel of Figure 1; e.g., the health benefits of working out) may be preferred when both alternatives are delayed, but preference may shift to the smaller, more immediate reinforcer (i.e., shorter vertical line, left of the larger reinforcer; e.g., drinking at happy hour) as the delay to both alternatives decreases (i.e., preference reverses). These preference reversals are a hallmark feature of individuals suffering from addiction, as they often express a desire to abstain when drugs are not immediately available, but may reverse this preference when the opportunity to use is more proximal. This process has been likened to “loss of control” (Ainslie, 2001) or relapse (Brandon et al., 1990; Kirshenbaum et al., 2009; Marlatt et al., 1988; Nides et al., 1995; Norregaard et al., 1993; Shiffman et al., 1996; Westman et al., 1997; Yoon et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

This figure shows the predicted values of two reinforcers as a function of the delay until their receipt as predicted by the exponential model (left panel, 1a) and hyperbolic model (right panel, 1b). The height of the vertical lines represents the magnitudes of two reinforcers. The relative height of the solid and dashed curves represents preference for the two reinforcers. From Monterosso & Ainslie, 2007.

Excessive delay discounting in addiction

Delay discounting as a marker of addiction

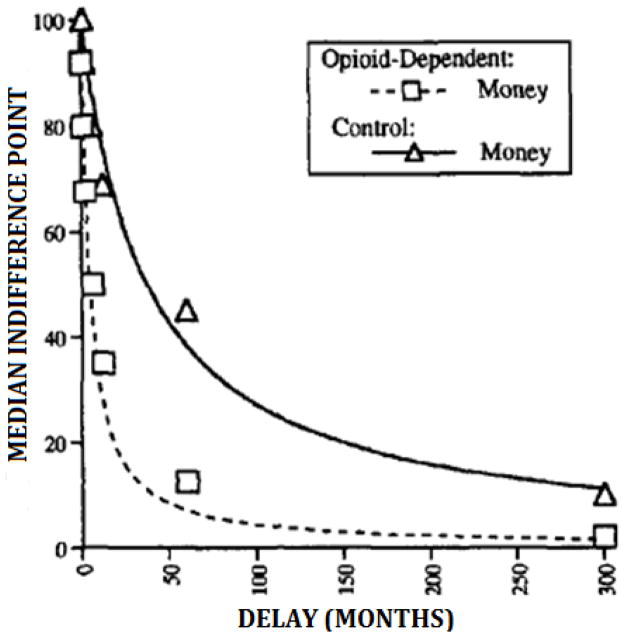

Abnormally high delay-discounting rates are associated with the addiction to, or abuse of, numerous drugs. For example, Madden et al. (1997) compared the discounting of hypothetical monetary reinforcers ($1000) in opioid-dependent individuals to those of non-drug-using controls. Figure 2 shows the median indifference points (expressed as a percentage of $1,000; Y-axis) for the group of opioid-dependent individuals (squares) and control participants (triangles) as a function of delay until the larger reinforcer (X-axis). The heights of the data points for the opioid-dependent individuals relative to controls (and the coordinated curves) reflect significantly higher discounting rates for the opioid-dependent patients (k = 0.220) than for the control group (k = 0.027). In other words, value of delayed reinforcers diminished faster in the opioid group than the control group. These elevated rates of discounting have been replicated in other studies comparing opioid dependent individuals to controls (Kirby & Petry, 2004; Kirby et al., 1999; Vassileva et al., 2011), comparing adult cigarette smokers to non-smokers (Baker et al., 2003; Bickel et al., 1999; 2008; Businelle et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2007; Mitchell, 1999; Odum et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 2009; 2004; Rezvanfard et al., 2010), comparing adolescent cigarette smokers to non-smoking adolescents (Fields et al., 2009; Reynolds et al., 2007), comparing alcoholics to healthy controls (Bjork et al., 2004; Bobova et al., 2009; Finn & Hall, 2004; Mitchell et al., 2005; Petry 2001a), and comparing cocaine-dependent persons with healthy controls (Allen et al., 1998; Bickel, Landes et al., in press; Camchong et al., 2011; Coffey et al., 2003; Heil et al., 2006; Kirby & Petry, 2004; Moeller et al., 2002; Petry & Casarella, 1999) (see Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Madden & Bickel, 2009 for reviews).

Figure 2.

Sample curves comparing the median discounting rates of a group of opioid dependent individuals to those of healthy controls. The y-axis shows the median indifference points expressed as a percentage of the immediate reinforcer for the opioid dependent (squares) and control (triangles) groups. The x-axis shows the delay until the larger reinforcer. The dashed and solid lines show the hyperbolic functions fit to the data from the opioid-dependent and control groups, respectively. Figure adapted from Madden et al., 1997.

The notion that excessive delay discounting is a marker of addiction is supported by findings that suggest that relatively greater severity of substance abuse may be associated with relatively higher rates of delay discounting. For example, Vuchinich and Simpson (1998) assessed the delay discounting rates of heavy and light social drinkers. These classes of participants were obtained by excluding from potential participants those who abstained from alcohol use or whose score (> 4) on the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST; Selzer, 1971) indicated they had an alcohol problem. Among non-excluded participants, heavy and light social drinkers were defined as those appearing on the upper and lower extremes, respectively, of the distribution of annual absolute alcohol intake scores, an estimate of total yearly alcohol consumption yielded by the Khavari Alcohol Test (KAT; Khavari & Farber, 1978). Vuchinich and Simpson found that heavy social drinkers’ k values were significantly greater than those of light social drinkers. They also assessed the discounting rates of light social drinkers and problem drinkers, who had scores in the upper extreme of the AAAI distribution and also reported 5 or more alcohol problems in the past year on the Young Adult Alcohol Problem Screening Test (Hurlbut & Sher, 1992). Vuchinich and Simpson found that problem drinkers’ k values were also significantly greater than those of the light social drinkers. Although Vuchinich and Simpson (1998) did not conduct an experiment comparing discounting rates in heavy social drinkers and problem drinkers, their findings suggest that the severity of substance abuse may be correlated with degree of delay discounting. This speculation is supported by findings that, much like drinking status, delay discounting rates are positively correlated with ones’ frequency of alcohol (Takahashi et al., 2009) and cigarette (Ohmura et al., 2005) use (see also Johnson et al., 2007).

By manipulating levels of drug deprivation, studies have investigated the relation between delay discounting rates and situational changes in the extent to which a drug is reinforcing. For example, Giordano et al. (2002) compared outpatients’ delay discounting rates when they were experiencing mild opioid deprivation to those when they were not deprived. Giordano et al. (2002) found that mild opioid deprivation increased rates of delay discounting for heroin and for money. Field et al. (2006) replicated this relation between drug deprivation (abstinence from smoking) and delay discounting rates for money and the drug of dependence. Mitchell (2004), however, found that deprivation increased discounting rate for cigarettes but not for money. Therefore, existing studies of situational drug deprivation provide qualified support for the association between abnormally high rates of delay discounting and the extent to which a drug is reinforcing.

Contributions of Discounting to Our Understanding of Addiction

Discounting and the time course of addiction

The literature reviewed above suggests that delay discounting is a trans-disease process that co-occurs across a range of addictions. Although this literature is extensive, the role that delay discounting plays in addiction remains somewhat unclear. There are three main time points in addiction: the point one begins to use (hereafter “entry”), the period of ongoing use (hereafter “maintenance”), and the point at which one stops using (hereafter “exit”). Studies examining each of these three phases provide different, yet complementary, information about the processes of addiction. Because the literature reviewed above focuses on the maintenance phase of addiction, the studies reviewed in this section will focus on unique contributions of studies on the entry and exit phases of addiction.

One persistent question in addiction research is if excessive rates of discounting precede (i.e., predispose one to addiction), or are simply the consequence of ongoing substance abuse. Information on the etiology of addiction will be found in longitudinal studies that elucidate factors associated with entry into addiction. For example, Audrain-McGovern et al. (2009a) followed a large cohort (n=947) of adolescents from the ages of 15 until 21. They found that although individuals’ rates of delay discounting did not change over time, delay discounting predicted entry into smoking and increases in smoking rates. Hence, Audrain-McGovern et al.’s (2009a) findings suggest that high rates of discounting predispose teens to the development of addiction. Few studies of this type, however, have been conducted. Future research efforts, working within this tradition, will shed light on the etiology of smoking and other forms of addiction, and clarify whether the trans-disease process of delay discounting is a contributing cause of entry into addiction.

Studies of the exit phase of addiction may provide additional information about the impact of substance use on delay-discounting rates. For example, Bickel et al. (1999) compared the discounting rates of current and former smokers to those of healthy controls (i.e., never smokers). Interestingly, although discounting rates were highest in the current smokers, discounting rates did not differ between the former and never smokers. There have been similar findings in a study wherein smokers were required not to quit smoking, but to cut down on the number of cigarettes they smoked (Yi et al., 2008), and in a study that assessed the discounting of health outcomes in cigarette smokers (Odum et al., 2002). These findings suggest that discounting rates may be elevated in addicted populations due to ongoing substance use (cf. Petry, 2001a). Hence, although elevated discounting rates may predispose individuals to addiction, ongoing use may result in even higher rates of discounting. This may result from substance abusers disuse of the skills associated with self-controlled choice in favor of the immediate reinforcement of drug self administration. The cross sectional nature of these studies, however, makes it difficult to definitively determine if the comparatively lower discounting rates seen in former addicts are due to ongoing substance use by current addicts, or if lower discounters are more likely to become abstinent. Moreover, the elevated rates of discounting in current, but not former smokers point to the importance of longitudinal studies which can clarify the role of high discounting rates in the initiation of drug abuse, and the role of ongoing drug abuse in increasing rates of discounting.

There, however, is evidence that individuals with lower delay discounting rates may be more likely to become abstinent after periods of ongoing drug use. For example, Sheffer et al. (in press) found that delay discounting rates significantly predicted abstinence after an intensive cognitive-behavioral treatment in highly dependent cigarette smokers. Other studies replicate this relation, showing that individuals with lower rates of delay discounting tend to be more responsive to treatment for nicotine dependence (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2007; MacKillop & Kahler, 2009; Yoon et al., 2007), or cocaine dependence (Washio et al., 2011). These studies suggest that former addicts may discount at a lower rate than current addicts (e.g., Bickel et al., 1999) because addicts with lower discount rates are better able to utilize treatment resources (Sheffer et al., in press). Like the entrance phase of addiction, however, a more complete understanding of the phenomenon awaits longitudinal studies.

Pharmacological considerations in delay discounting

In general, individuals abuse and become addicted to drugs that have a rapid and powerful onset (Bickel, Jarmolowicz et al., in press; Bickel, Mueller et al., in press; Schuster & Thompson, 1969). This is consistent with the rapid pharmacokinetic profile of many drugs that produce a subjective “high” (see Volkow et al., 2007 for a discussion). Interestingly, the chronic use of many drugs with a rapid and powerful onset is associated with high rates of delay discounting. For example, individuals that use cocaine (Bickel, Landes et al., in press; Coffey et al., 2003; Heil et al., 2006), methamphetamine (Hoffman et al., 2006), and heroin (Kirby & Petry, 2004; Madden et al., 1997) all discount delayed reinforcers at high rates.

Drugs of abuse, however, do not always have the same impact on rates of delay discounting when administered acutely. In fact, the acute administration of some drugs can affect delay discounting in the opposite direction than what would be expected from looking at comparisons of drug abusing populations to controls. For example, although chronic stimulant use is associated with elevated rates of delay discounting (Bickel, Landes et al., in press; Coffey et al., 2003; Heil et al., 2006; Hoffman et al., 2006), acute administration of d-amphetamine decreases rates of delay discounting in adults (de Wit et al., 2002). Likewise, alcohol-dependent adults discount delayed rewards at higher rates than non-dependent adults (Bobova et al., 2009; Dom et al., 2006), but acute alcohol administration has been shown to increase (Reynolds et al., 2006), decrease (Ortner et al., 2003), or have no effect on (Richards et al., 1999) discounting rates. These discrepancies are likely due to procedural differences among the studies (see Reynolds et al., 2006), but nonetheless make interpretation of these acute drug effects challenging. As a whole, there are relatively few published examples of acute drug effects on delay-discounting tasks in humans. Analogous experiments with animals are far more numerous, and have identified, for example, roles for selective serotonergic (e.g., Evenden & Ryan, 1999) and dopaminergic (e.g., Koffarnus et al., 2011; van Gaalen et al., 2006) drugs in acutely moderating delay discounting. Extrapolating results from animal studies is complicated by inconsistencies within the animal literature, but also across species. For example, central serotonin depletion has been shown to increase discounting rates in rats (Mobini et al., 2000), but a similar (although smaller in magnitude) manipulation had no effect in human subjects (Crean et al., 2002). Likewise, while d-amphetamine has been shown to decrease delay-discounting rates in humans (de Wit et al., 2002), animal studies show increases (e.g., Evenden & Ryan, 1996), decreases (e.g., van Gaalen et al., 2006) or no effect (e.g., Uslaner & Robinson, 2006) on discounting rates. Although the correlation between drug abuse and delay discounting rates is clear and consistent (above), further research on the acute drug effects on delay-discounting tasks is warranted to better understand the pharmacological and procedural variables that influence delay discounting.

Excessive discounting in problem gamblers, the obese, and poor health practices

Loss of control over drug-seeking behavior and excessive rates of discounting both characterize addiction. Interestingly, excessive discounting has also been demonstrated in other types of unhealthy behaviors that are characterized by loss of control. For example, problem gambling is an urge to gamble despite harmful negative consequences or a desire to stop. A number of studies have examined the relation between delay discounting rates of gamblers versus non-gamblers. Dixon et al. (2003) investigated the discounting rates of non-gamblers and gamblers who were recruited at an off-track betting facility and scored above the threshold for pathological gambling on the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOG; Lesieur & Blume, 1987). They found that the gamblers exhibited higher delay discounting rates. This relation between delay discounting rates and SOG scores was replicated in college students by MacKillop et al. (2006); but it was not observed in a study of college students by Holt et al. (2003) that used a smaller sample size and less stringent SOG scores to classify participants as gamblers. Madden et al. (2009) similarly found that differences in rates of delay discounting between treatment-seeking pathological gamblers and healthy controls only approached, but did not reach, statistical significance.

Interestingly, some studies have examined pathological gambling in individuals with substance-use disorder. Petry and Casarella (1999) found that substance abusers who were pathological gamblers had higher delay discounting rates than substance abusers who seldom gambled, and controls that did not abuse substances or gamble had the lowest discounting rates. That is, subjects with two disorders associated with higher rates of discounting had higher discounting rates than subjects with one such disorder, and subjects with no such disorder had the lowest discounting rates. These results suggested that the relation between disorders and discounting rates may be additive, such that individuals with disorder comorbidity may exhibit higher discounting rates than individuals with a single disorder. Petry (2001b) found similar evidence of this kind of relation between discounting rates and disorders. In that study, participants with diagnoses of both substance abuse and pathological gambling exhibited the highest discounting rates, lowest discounting rates were seen for controls with no diagnosis, and intermediate discounting rates were observed for those with only the diagnosis of pathological gambling. Ledgerwood et al. (2009) replicated Petry’s (2001b) observed difference between the discounting rates of pathological gamblers and controls, but Ledgerwood et al. (2009) did not observe a difference between gamblers with and without a substance abuse disorder.

Rates of delay discounting also have been studied in obese individuals. For example, Weller et al. (2008) assessed delay discounting among obese and healthy-weight men and women, and found that delay discounting rates distinguished obese women from healthy-weight women. In a study concerned with binge eating disorder (BED), Davis et al. (2010) studied obese women who did or did not have binge eating disorder and compared them to healthy-weight women. They replicated the finding that delay-discounting rates distinguish obese women from the healthy-weight women (without regard to whether they had BED). Zhang and Rashad (2008) found a positive relation between discounting of the future and body mass index (BMI). Fields et al. (2011) found that high delay discounting rates distinguish the obese and non-obese among adolescent smokers.

High rates of delay discounting are also seen in individuals who engage in behaviors associated with the contraction and spreading of HIV (e.g., needle sharing, risky sexual behavior, etc.). For example, although individuals addicted to heroin already have higher discounting rates than do controls (e.g., Madden et al., 1997), heroin users who share needles discount at even higher rates than those that do not (Odum et al., 2000). Additionally, Chesson et al. (2006) found that, in a large sample of adolescents (i.e., n=1042), rates of delay discounting were positively associated with a variety of sexual behaviors, including ever having sex, having sex before age 16, and past or current pregnancy. Hence, rates of monetary delay discounting are correlated with sexual behavior that is risky. Furthermore, higher rates of discounting than those of healthy controls are found in individuals who already have HIV (Dierst-Davies et al., 2011) or hepatitis C (Huckans et al., 2011).

High rates of delay discounting are also associated with behaviors that are precursors to poor health outcomes. For example, Daugherty and Brase (2010) had 467 college students complete a delay discounting questionnaire (Kirby et al., 1999) and answer a series of questions about how often they engaged in a range of health related behaviors. They found that delay discounting rates predicted college students’ health-related behaviors such as tobacco use, alcohol use, eating breakfast, using safety belts, using sunscreen, and risky sexual practices. Similarly, Bradford (2010) calculated discounting rates using data collected as part of the 2004 wave of the Health and Retirement Survey. This survey asked 987 retirement-age individuals a series of questions about money (e.g. would you rather have $1,100 now or $1,200 a year from now) as well as a number of questions about their health-related behaviors. He found that delay-discounting rates were negatively correlated with the probability of having a recent mammogram, Pap smear, prostrate examination, dental visit, cholesterol testing, flu shot usage, and rates of vigorous exercise. Axon et al. (2009) investigated the delay-discounting rates and health behaviors of a sample of hypertensive individuals. They found that discounting rates predicted (a) not following physicians’ treatment plans; (b) not checking blood pressure; (c) not altering diet and exercise habits in response to diagnosis of hypertension; and (d) not using their physician’s office for sick care.

Excessive discounting in psychiatric disorders

In addition to drug addiction and other behavioral maladies, excessive rates of delay discounting are associated with numerous psychiatric disorders. A number of studies have found that individuals suffering from schizophrenia, a psychiatric illness characterized by a disintegration of emotional and cognitive processes (“Concise Medical Dictionary,” 2010), discount delayed reinforcers at higher rates than do healthy controls (see Gold et al., 2008 for a discussion; Heerey et al., 2011; 2007). For example, Heerey et al., (2007) compared rates of delay discounting in 42 individuals with schizophrenia to those of 29 healthy controls. Individuals with schizophrenia discounted at a higher rate than did control participants, and these elevated rates of discounting were related to low levels of working memory. Interestingly, although this between-group difference between schizophrenics and healthy controls has been replicated (Heerey et al., 2011), MacKillop and Tidey (2011) were unable to demonstrate differences in discounting between smokers with and without schizophrenia. Thus, high rates of discounting exhibited by individuals with schizophrenia may be due to the high rates of smoking among individuals with schizophrenia, since it is known that smoking is associated with increased rates of discounting (e.g., Baker et al., 2003; Bickel et al., 1999).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurobehavioral developmental disorder that entails difficulty staying focused and paying attention, difficulty controlling behavior, and hyperactivity (i.e., over-activity) (NIMH). Studies have shown that children (Scheres et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2011), adolescents (Barkley et al., 2001; Scheres et al., 2010) and adults (Hurst et al., 2011; Scheres et al., 2008) with ADHD discount delayed reinforcers at higher rates than healthy controls. For example, Hurst et al. (2011) found that delay-discounting rates distinguished young adults who self-reported a diagnosis of ADHD from those who did not. These results, however, should be interpreted cautiously because, much like the relation between working memory and discounting rate in schizophrenia, these elevated rates of discounting have been linked to lower IQ in individuals with ADHD (Wilson et al., 2011).

Although fewer studies have focused on discounting rates in other psychiatric conditions, elevated discounting rates have also been observed across a range of other disorders. For example, studies have found elevated rates of discounting in those suffering from borderline personality disorder (see Bornovalova et al., 2005 for a review and discussion), depression (Yoon et al., 2007), social anxiety (Rounds et al., 2007), and disruptive behavior disorder (Swann et al., 2002).

Comorbidity and trans-disease processes

With high rates of delay discounting representing a common process occurring across a wide range of disorders, co-morbidity (e.g., substance abuse and mental illness) may be expected (see Bickel & Mueller, 2009 for a discussion). As a result, the high levels of co-morbidity between cigarette smoking and schizophrenia (Bobes et al., 2010; Fowler et al., 1998; Sagud et al., 2009) are not surprising. Similarly, the findings that individuals with ADHD are more likely to be addicted to cigarettes (Lambert & Hartsough, 1998; Laucht et al., 2007), smoke more than normal (Kollins et al., 2005; Lambert, 2000), and smoke at an earlier age (Kollins et al., 2005; Lambert, 2000) are consistent with the notion that rapid delay discounting is a process that underlies both of these disorders (i.e., smoking and ADHD).

In fact, co-morbidities between behavior patterns associated with delay discounting are relatively common. For example, in addition to the above-mentioned co-morbidity between ADHD and smoking, ADHD is also frequently co-morbid with obesity (see Davis, 2010, for a review), gambling (e.g., Grall-Bronnec et al., 2011), and addictions to drugs such as opioids (e.g., Carpentier et al., 2011). Similarly, obesity is often co-morbid with drug addiction (see Barry et al., 2009, for a review) and gambling (e.g., Pietrzak et al., 2007); and gambling is often co-morbid with addiction (see Lorains et al., 2011, for a review). These observed co-morbidities are consistent with the notion that excessive discounting is a trans-disease process underlying these disorders. Thus, understanding the commonalities in co-morbid disorders may inform treatment approaches for multiple disorders.

The Processes Behind Excessive Discounting

If excessive discounting describes a trans-disease process (Bickel & Mueller, 2009) that co- and re-occurs across many patterns of maladaptive responding (e.g., drug addiction, gambling, obesity, etc.), insights into the neurobiological substrates of these patterns of choices may improve our understanding of these various behavioral maladies. Specifically, understanding the neurobiological substrates that underlie excessive delay discounting rates may lead to novel approaches that target these processes, resulting in substantial improvements in the lives of individuals suffering from a wide range of behavioral maladies (e.g., drug addiction). In fact, delay discounting may be a behavioral manifestation of an underlying neurobiological imbalance in all of the maladies reviewed above (i.e., the real trans-disease process).

Insights into these neurobiological substrates may be found in recent advances in neuroeconomics, a relatively new discipline that leverages the concepts and methods of behavioral economics and neuroscience to identify the neurobiological constituents that underlie economic choices (Glimcher et al., 2008). For example, McClure and colleagues (2004) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the patterns of brain activation associated with the performance of delay-discounting tasks. They found that choices for the smaller more immediate reinforcer were associated with relatively high levels of activation in portions of the limbic system (e.g., paralimbic cortex) whereas choices for the larger later reinforcer were associated with relatively high levels of activation in areas of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., lateral prefrontal cortex, posterior parietal cortex).

The competing neurobehavioral decision systems theory

Consideration of findings like McClure et al. (2004) has led to the development of the competing neurobehavioral decisions systems (CNDS) theory (Bechara, 2005; Bickel, Jarmolowicz et al., in press; Bickel et al., 2007; Jentsch & Taylor, 1999). This approach to decision making posits that choices between immediate and delayed reinforcers are related to the regulatory balance of activation in two distinct neural systems. The evolutionarily older impulsive system, which consists of portions of the limbic and paralimbic areas (i.e., the amygdala, nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, and related structures), is primarily involved in the valuation of immediate rewards. By contrast, the more recently developed executive system, consisting of the prefrontal cortices, is involved in consideration of the future and the selection of delayed rewards. Thus, performance on delay-discounting tasks (i.e., discounting rate) can be seen as a relatively straightforward index of the relative strength of these competing decision systems.

Support for CNDS

A number of different types of data converge with McClure et al.’s (2004) findings to support the CNDS view. For example, like McClure et al., a number of studies have found that activation in the impulsive system is associated with the valuation of reinforcers (Bickel et al., 2009a; Kable & Glimcher, 2007, 2010; McClure et al., 2007; Monterosso et al., 2007b; Xu et al., 2009), and that this activation is diminished as reinforcers are delayed (Kable & Glimcher, 2007, 2010; Yan, 2009). Also consistent with McClure and colleagues, a number of fMRI studies have found that the valuation of delayed reinforcers is related to activity in the executive system (e.g., Bickel et al., 2009a; Hoffman et al., 2008; McClure et al., 2007; Meade et al., 2011; Monterosso et al., 2007a; Xu et al., 2009). Specifically, subjects choose delayed rewards, when there is greater activation in the executive than in the impulsive system.

Differential levels of activation in these two competing neurobehavioral systems may underlie addiction. For example, Meade et al. (2011) conducted a study wherein brain activity was measured via fMRI while HIV-positive volunteers completed delay-discounting tasks. Fifteen of the volunteers were active cocaine users, 13 were former users, and 11 had never tried cocaine. Significantly less executive system activation was observed in the active cocaine users than both the former and never users (Hoffman et al., 2006; Monterosso et al., 2007a).

Further evidence for CNDS can be found in disruptions in the balance of these competing systems by either trait- or state-oriented variables. Long-lasting (i.e., trait-like) influences such as differences in brain structure in individuals suffering from addiction may contribute to the high rates of discounting consistently exhibited by these individuals. For example, the executive systems of individuals suffering from drug addiction typically have lower cortical volume (e.g., Pezawas et al., 1998) and grey matter density (Liu et al., 2009; Lyoo et al., 2006) than do controls. Similar decreases in grey matter were not observed in the impulsive system (Liu et al., 2009; Lyoo et al., 2006). Furthermore, youth with a family history of alcoholism had white matter abnormalities in portions of the executive system (i.e., dorsolateral prefrontal and dorsomedial prefrontal cortices) that correlated with elevated rates of delay discounting (Herting et al., 2010). Although it is unknown whether these structural differences result from or predate prolonged drug use, longitudinal studies suggest that the elevated discounting rates may predate abuse (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009a).

State-like fluctuations may also influence these competing systems. For example, subjective reports of drug craving are associated with temporarily elevated levels of activation of the impulsive system (Risinger et al., 2005). Correspondingly, opioid addicts discount delayed reinforcers at higher rates during periods of deprivation than when they have had access to opioid replacement therapies such as buprenorphine (e.g., Giordano et al., 2002). Thus, the transient elevation in impulsive-system activation resulting from deprivation may disrupt the balance between these competing decision systems, resulting in elevated rates of discounting. Furthermore, manipulating the executive system can have similar effects on delay discounting rates. For example, Hinson et al. (2003) found that participants discounted delayed rewards more rapidly when they were concurrently required to remember a series of five digits than when no memory task was superimposed. This may be because an executive system that was temporarily taxed through its concurrent use in a working memory task could not effectively compete with the impulsive system.

CNDS as a dimensional view of addiction

Elevated discounting rates appear to be a risk factor for developing addiction (e.g., Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009a; Reynolds et al., 2009). According to the CNDS theory, the high rates of discounting associated with behavioral disorders such as drug addiction (see Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Madden & Bickel, 2009, for reviews) are related to a hyperactive impulsive and/or a hypoactive executive system (Bechara, 2005; Bickel, Jarmolowicz et al., in press; Bickel et al., 2007). Individuals are at risk of developing behavioral maladies whenever the impulsive system is stronger than the executive system. There, however, are a number of different ways that disruptions in the regulatory balance between the impulsive and executive systems can result in elevated risk of developing behavioral maladies such as drug addiction. For example, individuals with a weak executive system yet a moderately strong impulsive system and individuals with a moderately strong executive system yet very strong impulsive system are both at risk.

Moreover, the behavior of individuals with an approximate balance between the impulsive and executive systems may be more susceptible to the influence of state variables (e.g., context). For example, an individual with near threshold levels of risk may behave impulsively (e.g., take drugs) when in the context of stimuli associated with drug use (e.g., certain peers) but abstain in the presence of stimuli that do not encourage use. This possibility remains untested; however, it could be investigated by using fMRI to identify individuals with nearly balanced versus widely unbalanced relative activation of both brain regions prior to manipulating state variables (e.g., context).

Implications for Treatment

Conceptualizing excessive discounting rates as a trans-disease process may fuel the development of treatments for a range of behavioral maladies. Moreover, the dimensional view that the CNDS view promotes may allow for increased customization of an individual’s treatment. Specifically, the particular type of decision systems dysregulation can guide the treatment chosen for a given individual. Consider two cases where there is an imbalance related to addiction. In one case, the impulsive system is exhibiting intermediate levels of activation and the executive system is considerably weaker. In the other case the activation levels are very strong in the impulsive system and intermediate in the executive system. In the first case, improving activation of the executive system would likely be the recommended intervention strategy; whereas in the second example, suppression of the highly active impulsive system would likely be the target of the intervention.

Realization of the CNDS’s potential for treatment development, however, is dependent upon whether delay-discounting rates are trait-like and immutable, or state-like and malleable. As this issue is involved and has been described well elsewhere (Odum, 2011; Peters & Buchel, 2011), we will not discuss it in much more detail than the references to it above, where we pointed out that CNDS can account for the effects of both trait variables and state variables. In sum, the evidence regarding this issue suggests that delay discounting rate has features of a personality trait and also of a mutable (i.e., changeable), situational state (Odum, 2011).

If excessive delay discounting is a trans-disease process that is observed across a broad range of diseases, disorders and problematic behaviors, treatments that effectively treat one malady may be effective for multiple maladies. One example of a treatment being effective in individuals with different disorders is neurocognitive rehabilitation. Specifically, cognitive training approaches effective in the treatment of traumatic brain injury (Cicerone et al., 2006) have been successfully applied to the treatment of schizophrenia (Krabbendam & Aleman, 2003; Twamley et al., 2003) and Parkinson’s disease (Sammer et al., 2006). This effectiveness of one approach in multiple disorders suggests that the treatment is affecting a trans-disease process.

As we have argued, delay discounting can be viewed as a trans-disease process related to the relative balance of the executive and impulsive systems. According to CNDS, excessive delay discounting rates reflect a regulatory imbalance between the competing executive and impulsive systems of the brain (Bickel, Jarmolowicz et al., in press; Bickel et al., 2007). An implication of this reasoning is that enhancement of executive functioning may decrease rates of delay discounting. For example, because poor working memory is associated with higher rates of delay discounting (Shamosh et al., 2008), and because disorders with excessive discounting also appear to exhibit suboptimal working memory (Alloway, 2011; Cornoldi et al., 2001; Dige & Wik, 2005; Forbes et al., 2009; Landro et al., 2001; Re et al., 2010), training working memory may decrease rates of discounting. To test this notion, Bickel et al. (2011) conducted working memory training with stimulant users exhibiting deficits in working memory and excessive delay discounting. Bickel et al. (2011) exposed an “active training” group to working memory training, and a control group to stimuli that were similar except that the correct answers in the working memory exercises were provided. Pre- and post-training measures revealed that delay-discounting rates of the active training group declined while those for the control group remained unchanged. This study showed that operations intended to improve working memory did in fact decrease rates of delay discounting.

The above study may be a step on the path to remedies for a broad range of behavioral maladies that are associated with excessive discounting of future reinforcers. Further steps should be taken to affirm that decreases in delay discounting result in improved treatment outcomes, and to explore the functional relations between the discounting of future events and components of executive function other than working memory.

As was described above, enhancing the functioning of the executive system can decrease rates of delay discounting. Moreover, this diminution of discounting rate via working memory training may be supplemented through the use of pharmacological agents that decrease activation in the impulsive system. Psychopharmacological approaches such as the use of cognitive enhancers may alter the regulatory balance between the executive and impulsive decision systems. Cognitive enhancers are defined as medications that improve cognitive function by modulating neurotransmitters such as dopamine, GABA, glutamate, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine (Sofuoglu, 2010). An example is D-cycloserine (DCS), a partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Recent studies have demonstrated that behavioral therapies intended to reduce conditioned reactivity in phobic fear (Ressler et al., 2004), social anxiety disorder (Hofmann et al., 2006a; 2006b), panic disorder, (Otto et al., 2010), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Wilhelm et al., 2008) are enhanced when DCS is administered prior to the exposure and response prevention sessions. DCS appears to increase the rate at which learning occurs by modulating activity at NMDA receptors. Whether this would shift the balance between activation of the impulsive system and the executive function system remains to be determined. DCS is thus potentially a useful complement to executive function training.

Other novel approaches such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive brain stimulation method that induces electric currents in specified brain regions (Fecteau et al., 2010; Mishra et al., 2010), and the ability to provide biofeedback by imaging human brain function in real time using fMRI (real-time fMRI; deCharms, 2008) are potential treatments for addiction and other problematic behaviors. Based on the understanding that excessive discounting can be manipulated, new treatments can be addressed to changing the regulatory imbalance of the executive and impulsive decision systems that gives rise to this trans-disease process. Future research will address important questions about how effectively these potential new treatment variables may redress the balance between the impulsive and executive systems in the brain. And future research will address questions about combining treatment variables. For example, the results of future studies examining the efficacy of executive function therapy on reducing delay discounting and improving drug abuse treatment outcomes can directly explore whether a combination of treatment variables (i.e., executive function training and cognitive enhancers; executive function training and TMS) is more effective than one treatment type administered alone. Combining treatment variables in such a way may be analogous to the relation between using steroids and exercise to increase muscle mass. Steroids alone may be ineffective in improving strength and muscle size; but when used in concert with exercising of the targeted muscle groups, the effects may be greater than exercise alone.

Conclusion

In this paper, we suggested that excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers might function as a trans-disease process. To explore that notion, we briefly reviewed important procedural and analytical aspects of discounting and then demonstrated that not only is excessive discounting evident in drug addiction and other disorders such as obesity and ADHD, but also that individuals who excessively discount the future are less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors. Observing these excessively high rates of discounting across such a range of disorders and behaviors seems to indicate that excessive discounting does function as a trans-disease process.

Next, we reviewed the CNDS view, an emerging neuroeconomic theory of the neurobiological underpinnings of discounting. This theory is not only consistent with excessive discounting seen across a wide range of disorders (e.g., addiction) but also with other findings from studies using diverse measures and approaches. We then considered the implications of excessive discounting being a trans-disease process undergirded by CNDS. Specifically, the CNDS approach suggests restoring the balance between the two competing decision systems (i.e., the impulsive and executive systems) as a new target for intervention in addiction and other behavioral patterns or disorders associated with excessive discounting. Preliminary efforts using this approach, such as working memory training, have successfully reversed excessive discounting of delayed rewards. Systematic replication of these findings through the use of different interventions such as cognitive enhancers and TMS will further test the notion that excessive discounting is a trans-disease process.

Despite the initial advances of this research domain, each step forward will raise additional questions. Among the most interesting questions, from our perspective, are ones that address interventions for addiction: 1) What are the conditions that produce regulatory balance between the competing neurobehavioral decision systems? 2) Will induction of that regulatory balance be a necessary component of efficacious addiction treatment outcomes? 3) Could these interventions be adapted as part of a comprehensive prevention program for addiction? For each of these questions, the answer could inform treatment of various disorders (e.g., drug addiction, obesity, gambling, etc.). Only by answering these and many other important questions will the significance and power of these new perspectives be understood. If the discounting of delayed reinforcers is a trans-disease process that plays a causal role in therapies, and can be improved in ways consistent with the CNDS approach, then the stage may be set for advances in understanding and treating not only addiction, but related disorders as well.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDA grants R01DA030241; R01DA024080; R01DA012997; [NIAAA] R01DA024080-02S1. The authors would like to thank Patsy Marshall for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

Principal, HealthSim, LLC

101 West 23rd Street, Suite 525

New York, NY 10011

Company spectializes in the research and development of prevention science products.

The authors declare that there are no other potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ainslie G. Breakdown of Will. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TJ, Moeller FG, Rhoades HM, Cherek DR. Impulsivity and history of drug dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;50:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway TP. A comparison of working memory profiles in children with ADHD and DCD. Child Neuropsychology. 2011:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2011.553590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Wileyto EP. Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009a;103:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axon RN, Bradford WD, Egan BM. The role of individual time preferences in health behaviors among hypertensive adults: A pilot study. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension. 2009;3:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: Similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Edwards G, Laneri M, Fletcher K, Metevia L. Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:541–556. doi: 10.1023/a:1012233310098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry D, Clarke M, Petry NM. Obesity and its relationship to addictions: is overeating a form of addictive behavior? The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:439–451. doi: 10.3109/10550490903205579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RC, Triplett MF. Test-retest reliability of a group-administered paper-pencil measure of delay discounting. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:345–355. doi: 10.1037/a0017078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Gatchalian KM. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: Implications for etiology and treatment of addiction. Current Psychiatry Reports. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jones BA, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Mancino M. Hypothetical intertemporal choice and real economic behavior: delay discounting predicts voucher redemptions during contingency-management procedures. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:546–552. doi: 10.1037/a0021739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Jones BA, Kurth-Nelson Z, Redish AD. Single- and cross-commodity discounting among cocaine addicts: The commodity and its temporal location determine discounting rate. Psychopharmacology. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2272-x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA. Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: Competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90S:S85–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Mueller ET. Toward the study of trans-disease processes: A novel approach with special reference to the study of co-morbidity. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2009;5:131–138. doi: 10.1080/15504260902869147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Mueller ET, Jarmolowicz DP. What is addiction? In: McCrady B, Epstein E, editors. Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook. 2. Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJ. Equivalent neural correlates across intertemporal choice conditions. NeuroImage. 2009a;47:S39–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJC. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: fictive and real money gains and losses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009b;29:8839–8846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5319-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Kowal BP, Gatchalian KM. Cigarette smokers discount past and future rewards symmetrically and more than controls: Is discounting a measure of impulsivity? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the future: working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Hommer DW, Grant SJ, Danube C. Impulsivity in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients: Relation to control subjects and type 1-/type 2 like traits. Alcohol. 2004;34:133–150. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black AC, Rosen MI. A money management-based substance use treatment increases valuation of future rewards. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobes J, Arango C, Garcia-Garcia M, Rejas J. Healthy lifestyle habits and 10-year cardiovascular risk in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: an analysis of the impact of smoking tobacco in the CLAMORS schizophrenia cohort. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;119:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobova L, Finn PR, Rickert ME, Lucas J. Disinhibitory psychopathology and delay discounting in alcohol dependence: Personality and cognitive correlates. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:51–61. doi: 10.1037/a0014503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB, Zachary Rosenthal M, Lynch TR. Impulsivity as a common process across borderline personality and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:790–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford WD. The association between individual time preferences and health maintenance habits. Medical Decision Making. 2010;30:99–112. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09342276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: The process of relapse. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle MS, McVay MA, Kendzor D, Copeland A. A comparison of delay discounting among smokers, substance abusers, and non-dependent controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camchong J, Macdonald AW, 3rd, Nelson B, Bell C, Mueller BA, Specker S, Lim KO. Frontal hyperconnectivity related to discounting and reversal learning in cocaine subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier PJ, van Gogh MT, Knapen LJ, Buitelaar JK, De Jong CA. Influence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder on opioid dependence severity and psychiatric comorbidity in chronic methadone-maintained patients. European Addiction Research. 2011;17:10–20. doi: 10.1159/000321259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson HW, Leichliter JS, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Bernstein DI, Fife KH. Discount rates and risky sexual behavior among teenagers and young adults. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2006;32:217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone KD, Levin H, Malec J, Stuss D, Whyte J. Cognitive rehabilitation interventions for executive function: Moving from bench to bedside in patients with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:1212–1222. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.7.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:18–25. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornoldi C, Marzocchi GM, Belotti M, Caroli MG, Meo T, Braga C. Working memory interference control deficit in children referred by teachers for ADHD symptoms. Child Neuropsychology. 2001;7:230–240. doi: 10.1076/chin.7.4.230.8735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean J, Richards JB, de Wit H. Effect of tryptophan depletion on impulsive behavior in men with or without a family history of alcoholism. Behavioural Brain Research. 2002;136:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty JR, Brase GL. Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Davis C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Associations with overeating and obesity. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2010;12:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Patte K, Curtis C, Reid C. Immediate pleasures and future consequences. A neuropsychological study of binge eating and obesity. Appetite. 2010;54:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Enggasser JL, Richards JB. Acute administration of d-amphetamine decreases impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:813–825. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCharms RC. Applications of real-time fMRI. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:720–729. doi: 10.1038/nrn2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierst-Davies R, Reback CJ, Peck JA, Nuno M, Kamien JB, Amass L. Delay-discounting among homeless, out-of-treatment, substance-dependent men who have sex with men. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:93–97. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.540278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dige N, Wik G. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identified by neuropsychological testing. The International Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;115:169–183. doi: 10.1080/00207450590519058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Marley J, Jacobs EA. Delay discounting by pathological gamblers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dom G, D’haene P, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Impulsivity in abstinent early- and late-onset alcoholics: differences in self-report measures and a discounting task. Addiction. 2006;101:50–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Green L, Myerson J. Cross-cultural comparisons of discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards. The Psychological Record. 2002;52:479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, Ryan CN. The pharmacology of impulsive behaviour in rats: the effects of drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1996;128:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s002130050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, Ryan CN. The pharmacology of impulsive behaviour in rats VI: the effects of ethanol and selective serotonergic drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:413–421. doi: 10.1007/pl00005486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S, Fregni F, Boggio PS, Camprodon JA, Pascual-Leone A. Neuromodulation of decision-making in the addictive brain. Substance Use & Misuse. 2010;45:1766–1786. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Santarcangelo M, Sumnall H, Goudie A, Cole J. Delay discounting and the behavioural economics of cigarette purchases in smokers: the effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S, Leraas K, Collins C, Reynolds B. Delay discounting as a mediator of the relationship between perceived stress and cigarette smoking status in adolescents. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20:455–460. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328330dcff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields SA, Sabet M, Peal A, Reynolds B. Relationship between weight status and delay discounting in a sample of adolescent cigarette smokers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2011;22:266–268. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328345c855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Hall J. Cognitive ability and risk for alcoholism: Short-term memory capacity and intelligence moderate personality risk for alcohol problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:569–581. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes NF, Carrick LA, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Working memory in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:889–905. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler IL, Can VJ, Carter NT, Lewin TJ. Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24:443–455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano L, Bickel WK, Loewenstein G, Jacobs EA, Marsch L, Badger GJ. Mild opioid deprivation increases the degree that opioid-dependent outpatients discount delayed heroin and money. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher PW, Camerer C, Poldrack RA, Fehr E. Neuroeconomics: Decision Making and the Brain. London, England: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Waltz JA, Prentice KJ, Morris SE, Heerey EA. Reward processing in schizophrenia: A deficit in the representation of value. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:835–847. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grall-Bronnec M, Wainstein L, Augy J, Bouju G, Feuillet F, Venisse JL, Sebille-Rivain V. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among pathological and at-risk gamblers seeking treatment: A hidden disorder. European Addiction Research. 2011;17:231–240. doi: 10.1159/000328628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Estle SJ. Preference reversals with food and water reinforcers in rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2003;79:233–242. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2003.79-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Lichtman D, Rosen S, Fry AF. Temporal discounting in choice between delayed rewards: The role of age and income. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:79–84. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA, Matveeva TM, Gold JM. Imagining the future: Degraded representations of future rewards and events in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:483–489. doi: 10.1037/a0021810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA, Robinson BM, McMahon RP, Gold JM. Delay discounting in schizophrenia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12:213–221. doi: 10.1080/13546800601005900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Johnson MW, Higgins ST, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in currently using and currently abstinent cocaine-dependent outpatients and non-drug-using matched controls. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1290–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herting MM, Schwartz D, Mitchell SH, Nagel BJ. Delay discounting behavior and white matter microstructure abnormalities in youth with a family history of alcoholism. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1590–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson JM, Jameson TL, Whitney P. Impulsive decision making and working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2003;29:298–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WF, Moore M, Templin R, McFarland B, Hitzemann RJ, Mitchell SH. Neuropsychological function and delay discounting in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:162–170. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WF, Schwartz DL, Huckans MS, McFarland BH, Meiri G, Stevens AA, Mitchell SH. Cortical activation during delay discounting in abstinent methamphetamine dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Meuret AE, Smits JAJ, Simon NM, Pollack MH, Eisenmenger K, Shiekh M, Otto MW. Augmentation of exposure therapy with D-cycloserine for social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006a;63:298–304. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Pollack MH, Otto MW. Augmentation treatment of psychotherapy for anxiety disorders with D-cycloserine. CNS Drug Reviews. 2006b;12:208–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DD, Green L, Myerson J. Is discounting impulsive? Evidence from temporal and probability discounting in gambling and non-gambling college students. Behavioural Processes. 2003;64:355–367. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckans M, Seelye A, Woodhouse J, Parcel T, Mull L, Schwartz D, Mitchell A, Lahna D, Johnson A, Loftis J, Woods SP, Mitchell SH, Hoffman W. Discounting of delayed rewards and executive dysfunction in individuals infected with hepatitis C. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011;33:176–186. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.499355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst RM, Kepley HO, McCalla MK, Livermore MK. Internal consistency and discriminant validity of a delay-discounting task with an adult self-reported ADHD sample. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2011;15:412–422. doi: 10.1177/1087054710365993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: Implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:373–390. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F. Moderate drug use and delay discounting: A comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:187–194. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, Glimcher PW. The neural correlates of subjective value during intertemporal choice. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:1625–1633. doi: 10.1038/nn2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, Glimcher PW. An “as soon as possible” effect in human intertemporal decision making: behavioral evidence and neural mechanisms. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;103:2513–2531. doi: 10.1152/jn.00177.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khavari KA, Farber PD. A profile instrument for the quantification and assessment of alcohol consumption. The Khavari Alcohol Test. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1978;39:1525–1539. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1978.39.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR. An additive-utility model of delay discounting. Psychological Review. 2009;116:602–619. doi: 10.1037/a0016414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction. 2004;99:461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenbaum AP, Olsen DM, Bickel WK. A quantitative review of the ubiquitous relapse curve. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Newman AH, Grundt P, Rice KC, Woods JH. Effects of selective dopaminergic compounds on a delay discounting task. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2011;22:300–311. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283473bcb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]