Abstract

Background

Several clinical trials have shown that vernakalant is effective in terminating recent-onset atrial fibrillation (AF). The electrophysiological actions of vernakalant are not fully understood.

Methods and Results

Here we report the results of a blinded study comparing the in vitro canine atrial electrophysiological effects of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol. Action potential durations (APD50,75,90), effective refractory period (ERP), post-repolarization refractoriness (PRR), maximum rate of rise of the action potential (AP) upstroke (Vmax), diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE), conduction time (CT), and the shortest S1-S1 permitting 1:1 activation (S1-S1) were measured using standard stimulation and microelectrode recording techniques in isolated normal, non-remodeled canine arterially-perfused left atrial preparations. Vernakalant caused variable but slight prolongation of APD90 (p=n.s.), but significant prolongation of APD50 at 30 µM and rapid rates. In contrast, ranolazine and dl-sotalol produced consistent concentration- and reverse rate-dependent prolongation of APD90. Vernakalant and ranolazine caused rate-dependent, whereas dl-sotalol caused reverse rate-dependent, prolongation of ERP. Significant rate-dependent PRR developed with vernakalant and ranolazine, but not with dl-sotalol. Other INa-mediated parameters (i.e., Vmax, CT, DTE, and S1-S1) were also significantly depressed by vernakalant and ranolazine, but not by dl-sotalol. Only vernakalant elevated AP plateau voltage, consistent with blockade of IKur and Ito.

Conclusions

In isolated canine left atria, the effects of vernakalant and ranolazine were characterized by use-dependent inhibition of sodium channel-mediated parameters and those of dl-sotalol by reverse rate-dependent prolongation of APD90 and ERP. This suggests that during the rapid activation rates of AF, the INa blocking action of the mixed ion channel blocker vernakalant takes prominence. This mechanism may explain vernakalant’s anti AF efficacy.

Keywords: pharmacology, electrophysiology, sodium channel block, atrial fibrillation

Introduction

There is a need for effective and safe agents for rhythm control of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Prolongation of the effective refractory period (ERP) of atrial myocardium is commonly associated with anti-arrhythmic outcomes. The drug-induced electrophysiological changes required for prolongation of the ERP include increased action potential duration (APD70–90) and the development of the post repolarization refractoriness (PRR); where refractoriness extends beyond APD. The former is commonly due to block of potassium channels and the latter is due to inhibition of sodium channel. These electrophysiological changes are not necessarily confined to the atria, but can also interfere with ventricular repolarization and impulse conduction and thus may induce ventricular arrhythmias. Therefore, an ideal drug for the treatment of AF should selectively affect the electrophysiological properties of the atria only, leaving the ventricles unaffected.

Vernakalant, a novel antiarrhythmic agent, has shown efficacy in terminating recent onset AF.1–4 Vernakalant inhibits a number of potassium channel currents, i.e., the ultra-rapid delayed rectified potassium current (IKur), the transient outward potassium current (Ito), the rapidly activating delayed rectified potassium current (IKr), and the acetylcholine-regulated inward rectifying potassium current (IK-ACh).5 In addition, vernakalant inhibits cardiac sodium channels in a voltage- and frequency-dependent manner.5 Although vernakalant inhibits IKr, effects on ventricular repolarization are limited due to concomitant blockade of late INa.6 In humans, dogs, and pigs, vernakalant has been shown to preferentially increase the atrial vs. ventricular ERP.7–9 In atrial tissue isolated from patients in permanent AF, vernakalant prolonged APD90 and ERP.10 The present study was conducted to better understand the atrial electrophysiological effects of vernakalant associated with its antiarrhythmic actions. The chief aim of the present study was to compare the electrophysiological effects of vernakalant with those caused by ranolazine, which inhibits peak INa, late INa, and IKr, and dl-sotalol, which primarily blocks IKr, in normal, non-remodeled coronary-perfused canine left atria.

Methods

Class A Beagle Dogs (10 females and 11 males) weighing 20–35 kg were anticoagulated with heparin and anesthetized with pentobarbital (30–35 mg/kg, i.v.). The chest was opened via a left thoracotomy, and the heart was excised, placed in a cardioplegic solution consisting of cold (4°C) or room temperature Tyrode's solution containing 12 mM [K+]o and transported to a dissection tray.

Arterially-perfused left atrial (LA) preparation

The isolated LA coronary-perfused preparation consisted of the appendage and surrounding areas, without pulmonary vein (PV), and with a portion of the left ventricle attached. The LA preparations were cannulated through the left circumflex coronary artery using polyethylene tubing (i.d., 1.75 mm; o.d., 2.1 mm) and perfused with cold Tyrode’s solution (12–15°C) containing 8.5 [K+]0. With continuous coronary perfusion, all severed atrial and ventricular coronary branches were ligated using a silk thread. The entire procedure of cannulation and ligation of the LA preparations took <15 min. The coronary-perfused LA preparations were placed in a temperature-controlled bath (8 × 6 × 4 cm) and perfused with Tyrode’s solution at a rate of 8–10 mL/min. The Tyrode’s solution contained (in mM): NaCl 129, KCl 4, NaH2PO4 0.9, NaHCO3 20, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.5, and D-glucose 5.5, buffered with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. (37.0±0.5°C). The initial temperature of the coronary perfusate was 30°C and warmed to 37°C over a period of 5–6 min. The temperature was maintained at 37°C (Cole Parmer Instrument. Co., IL). The perfusate was circulated around the bottom of the bath through a metal hypo tube (Small Parts Inc. Miami, Fl) before flowing to the preparation so that the temperature of the perfusate matched that of the bath. The perfusate was delivered to the artery by a roller pump. An air trap was used to avoid bubbles in the perfusion line. Perfused atrial preparations were allowed to equilibrate in the tissue bath until electrically stable, usually 30 min, while pacing at cycle lengths (CL) of 500 to 800 ms. Basic stimulation was applied using a pair of thin silver electrodes insulated except at their tips

Transmembrane action potentials (AP; sampling rate 41 kHz) were recorded using floating glass microelectrodes (2.7 M KCl, 10–25 MΩ DC resistance) connected to a high input impedance amplification system (World Precision Instruments). The signals were displayed on oscilloscopes, amplified, digitized and analyzed (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England) and stored on computer hard drive or CD. Electronic differentiation of the action potential to obtain Vmax was accomplished using operational amplifiers or digitally using a sampling rate of 41 kHz.11, 12 A pseudo-electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded using two electrodes consisting of Ag/AgCl half cells placed in the Tyrode’s solution 1.0 to 1.2 cm from the opposite ends of the preparation, thus measuring the electrical field of the preparation as a whole. The diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE) was determined by increasing stimulus intensity in 0.01 mA steps starting from 0.1 mA, until a steady 1:1 activation was achieved The effective refractory period (ERP) was measured by delivering premature stimuli after every 10th regular beat (with 5 to 10 ms resolution; stimulation with a 2 × DTE amplitude). Post-repolarization refractoriness (PRR) was defined as the difference between ERP and action potential duration at 75% repolarization (APD75; ERP corresponds to APD70–75 in the atria).13, 14 Maximum rate of rise of the AP upstroke (Vmax): Stable AP recordings and Vmax measurements are difficult to obtain in vigorously contracting perfused preparations. A large variability in Vmax measurements is normally encountered under any given condition, primarily due to variability in the amplitude of phase 0 of the AP which strongly determines Vmax values. The effects of the test drugs on Vmax were determined by comparing the largest Vmax recorded under any given condition at a CL of 500 ms. Changes in Vmax values upon acceleration from a CL of 500 to 300 ms were determined as well. Due to a substantial inter-preparation variability, Vmax values were normalized to a CL of 500 ms for each experiment and then averaged. Conduction Time (CT): Changes in conduction velocity were assessed by measuring the duration of the ECG activation (P) wave (at 50% of total amplitude of P wave).

Experimental Protocols (n=6, 5, and 6 atrial preparations for vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol, respectively). The following parameters were measured: APD50, APD75, APD90, ERP, PRR, Vmax, DTE, CT, and the shortest S1–S1 showing 1:1 conduction. Most of these parameters were recorded/measured at a basic cycle length (CL) of 1000, 500 and 300 ms. The drugs tested were randomly assigned and blinded to all involved with the conduct of the experimental study, with the blinded test agent code broken only after completion of all studies and data analysis. Left atrial AP measurements were obtained from the epicardial surface of the appendage. The effect of each drug on the electrophysiology of the left atria was evaluated at 3 distinct concentrations (3, 10, 30 µM). The tissues were exposed to each concentration of the drug for a period of 20–30 min.

Time control experiments (n=4) were performed to assess the stability of the preparation over a period of 2 hours after the end of the equilibration period. The time control studies were designed to match the duration of the experimental protocols.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using, unpaired t-test as well as one way repeated measures or multiple comparison analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s test, as appropriate. An unpaired t-test was used to compare two sets of independent parameters (APD70 vs. ERP). The null hypothesis of an unpaired t-test was tested. One way repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare the changes in the same parameters (APD, ERP, etc) induced by three progressively increasing concentrations of each drug as well as respective time controls. One way ANOVA was used to test the hypothesis of no differences between the several treatment groups. A multiple comparison procedure (Bonferroni’s test) was used to isolate the control group that differed from the others. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

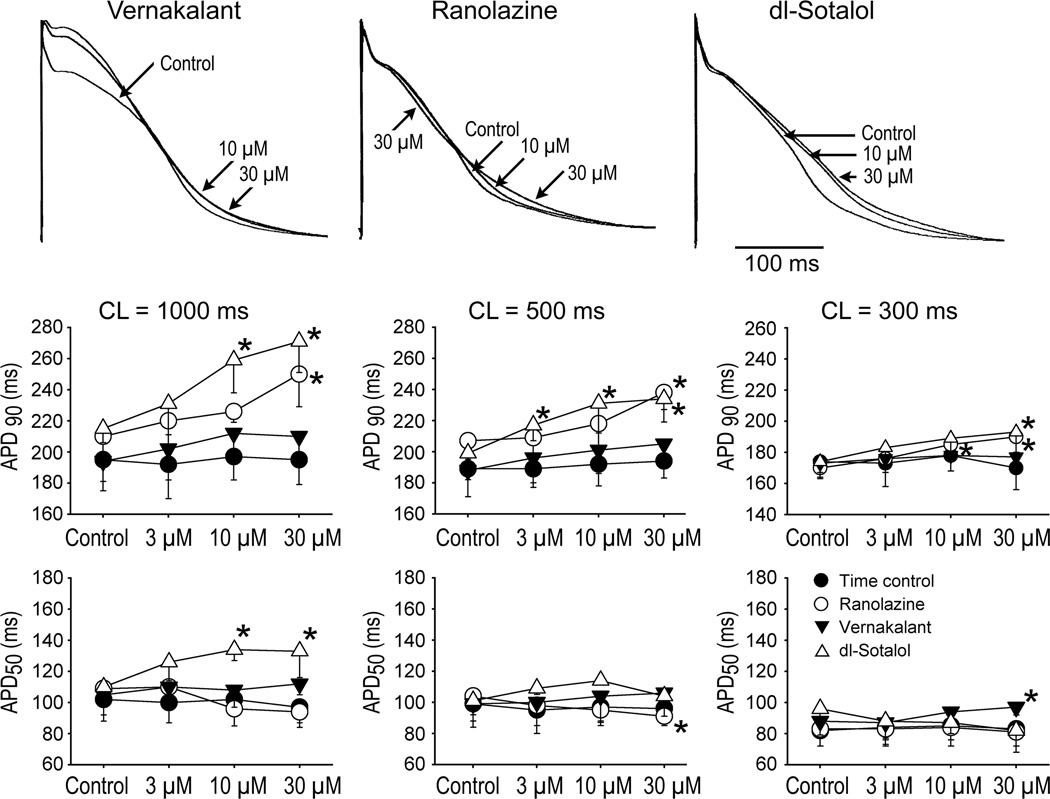

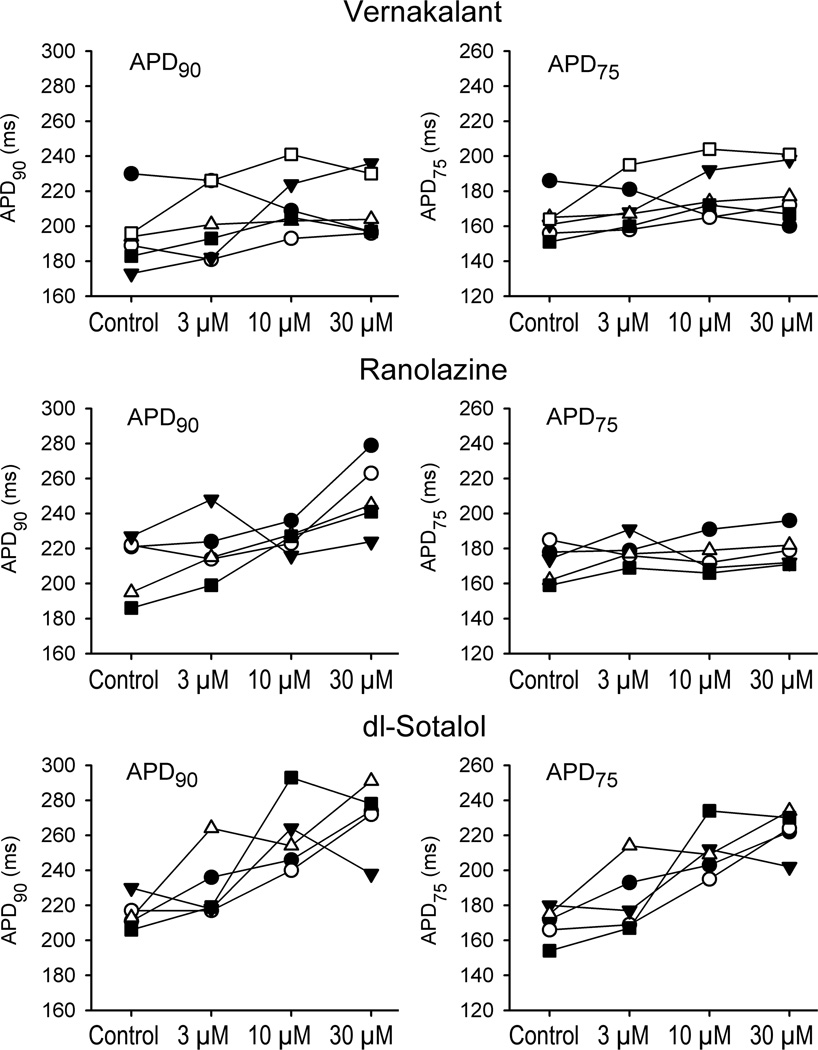

Generally, ranolazine and d,l-sotalol produced a concentration- and reverse rate-dependent prolongation of APD90 (Fig. 1). Vernakalant caused a variable effect on APD90 (with abbreviation, prolongation, or no change being recorded) on average giving rise to no significant change in APD90 (Fig. 1), although examination of individual experiments (CL=1000 ms) indicates that most vernakalant-treated preparations tended to display modest increases in APD90 (Fig 2). APD50 was consistently prolonged by d,l-sotalol at 10 and 30 µM at a CL of 1000 ms (Fig. 1). Vernakalant (30 µM) statistically significantly prolonged APD50 at a CL of 300 ms. Ranolazine tended to abbreviate APD50, reaching statistical significance at a CL of 500 ms at 30 µM (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol on action potential duration measured at 90 and 50% repolarization (APD90 and APD50) in coronary-perfused left atria.

Upper panels: Superimposed action potentials recorded at a CL of 500 ms. Lower panels: Mean data for the effect of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol on APD90 and APD50. N=4–6. *- p<0.05 vs. respective control.

Figure 2.

APD90 and APD75 data from individual experiments for the three drugs (n=5–6) recorded at a pacing CL of 1000 ms.

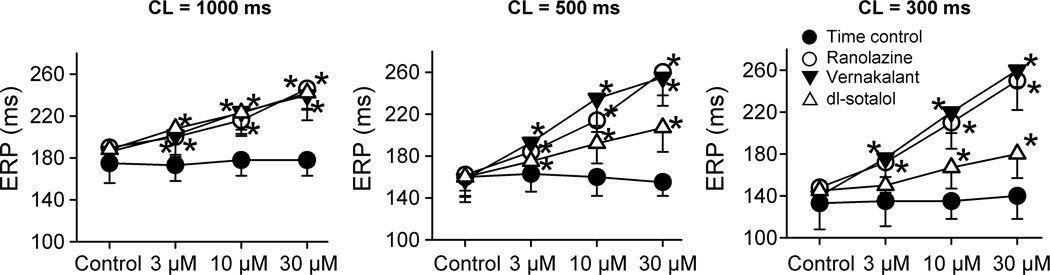

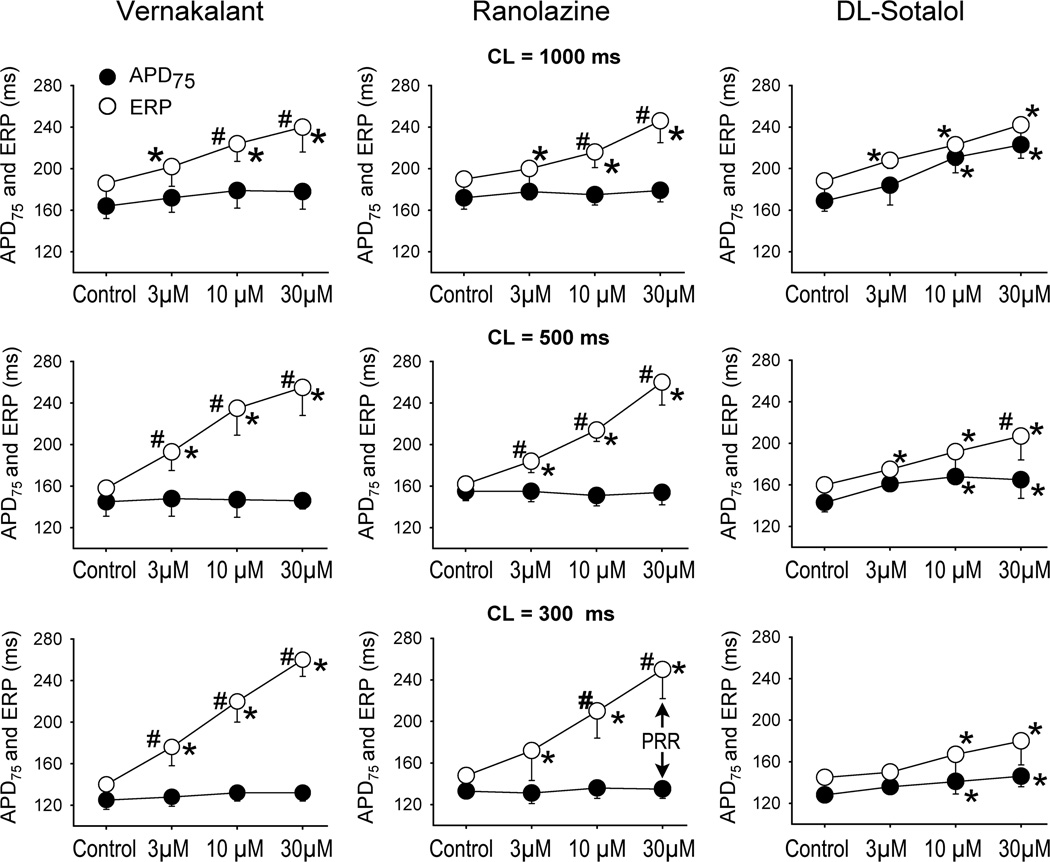

ERP was increased by all test agents in a concentration-dependent manner, but there were important rate-dependent differences between the three compounds (Fig. 3). At the slowest pacing rate tested (CL = 1000 ms), all three compounds caused similar ERP prolongation. At faster pacing rates (CL = 500 and 300 ms), the efficacy of dl-sotalol to prolong ERP was reduced and those of vernakalant and ranolazine were increased (Fig. 3). In atria, the voltage level of ERP corresponds to the level of APD70–75.13, 14 Prolongation of APD75 by ranolazine and vernakalant contributed modestly to ERP prolongation induced by these agents at the longest cycle length (1000 ms), and this contribution decreased or disappeared at CLs of 500 and 300 ms (Fig 4). Rate-dependent lengthening of ERP by vernakalant and ranolazine was largely due to the development of PRR (Fig. 4), a parameter known to arise as sodium channel activity diminishes. At a concentration of 30 µM, dl-sotalol also induced some PRR at a CL of 500 ms, but to a much lesser extent than vernakalant and ranolazine.

Figure 3.

Rate- and concentration-dependent prolongation of effective refractory period (ERP) by vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol in coronary-perfused left atria. N=4–6.*- p<0.05 vs. respective control.

Figure 4.

Rate-dependent change in ERP relative to change in APD75 in response to vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol. The difference between ERP and APD75 approximates post-repolarization refractoriness (PRR). In left atria, ERP is coincident with APD75–80 under control conditions. n=4–6. *- p<0.05 vs. respective control. # p <0.05 vs. corresponding APD75 value.

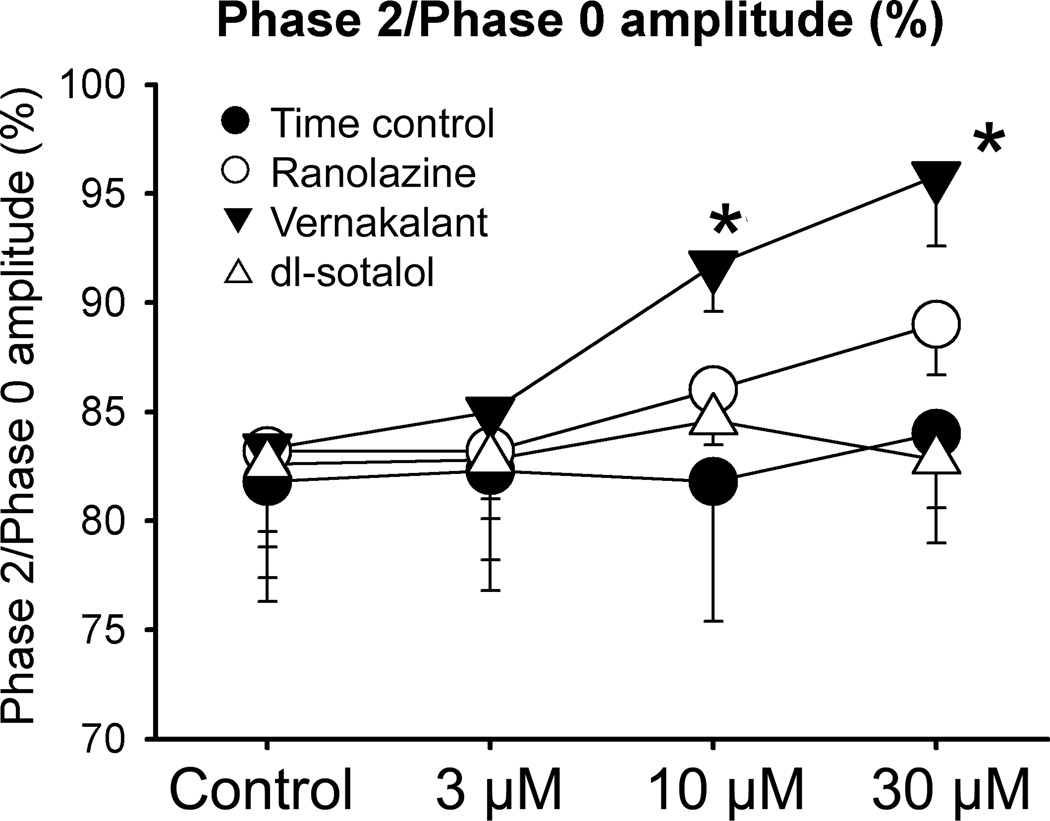

The AP plateau voltage was elevated by vernakalant, but not by ranolazine and dl-sotalol (Fig. 1 and 5). The instability of AP recordings due to vigorous contraction of the preparations made it difficult to precisely measure AP amplitude. To quantify changes in AP amplitude, we normalized the amplitude of phase 2 to that of phase 0 (in cases in which the peak of phase 2 was difficult to determine, the plateau amplitude 25 ms after the start of AP was selected).

Figure 5.

Effect of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol on the amplitude of phase 2 of atrial action potential recorded from coronary-perfused left atrial preparations. The changes in phase 2 were approximated by normalizing phase 2 amplitude to Phase 0 amplitude. Data were obtained at a CL of 500 ms. N=4–6 *- p<0.05 vs. control.

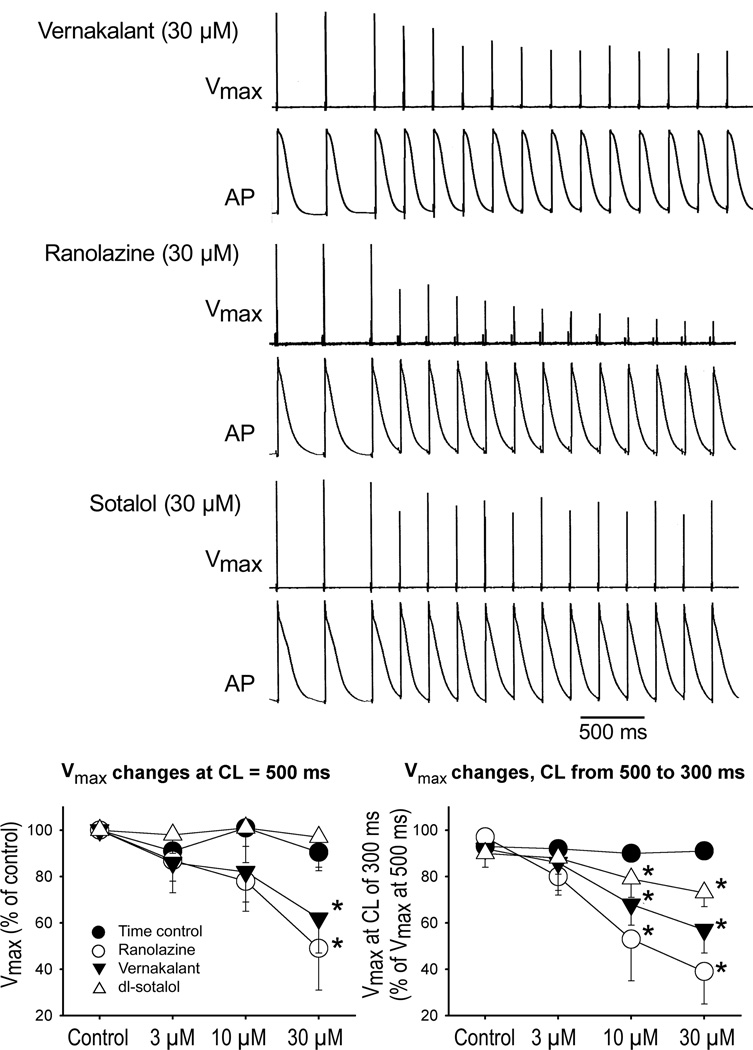

Vmax was consistently reduced by vernakalant and ranolazine at a CL of 500 ms (Fig. 6). Alterations in Vmax were not detected with dl-sotalol at a CL of 500 ms. Ranolazine produced the greatest reduction of Vmax in response to a decrease of CL from 500 to 300 ms, followed by vernakalant (Fig. 6, lower right panel). There was a slight decrease of Vmax at a CL of 300 ms in the presence of dl-sotalol (Fig. 6). This can be explained, at least in part, by a depolarization of the take-off potential at a CL of 300 ms due to prolongation of APD (Fig. 1).

Figure 6.

Effect of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol on in maximum rate of rise of the action potential upstroke (Vmax). Upper panels: Typical examples of use-dependent reduction of Vmax upon decrease of CL from 500 to 300 ms with vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol. Bottom panels: Normalized changes at a CL of 500 ms (left plot) and upon abbreviation of CL from 500 to 300 ms (right plot) in the absence and presence of drugs. Right plot: Vmax value at a CL of 500 ms was taken as 100% for each condition. N=3–5 *- p<0.05 vs. respective control.

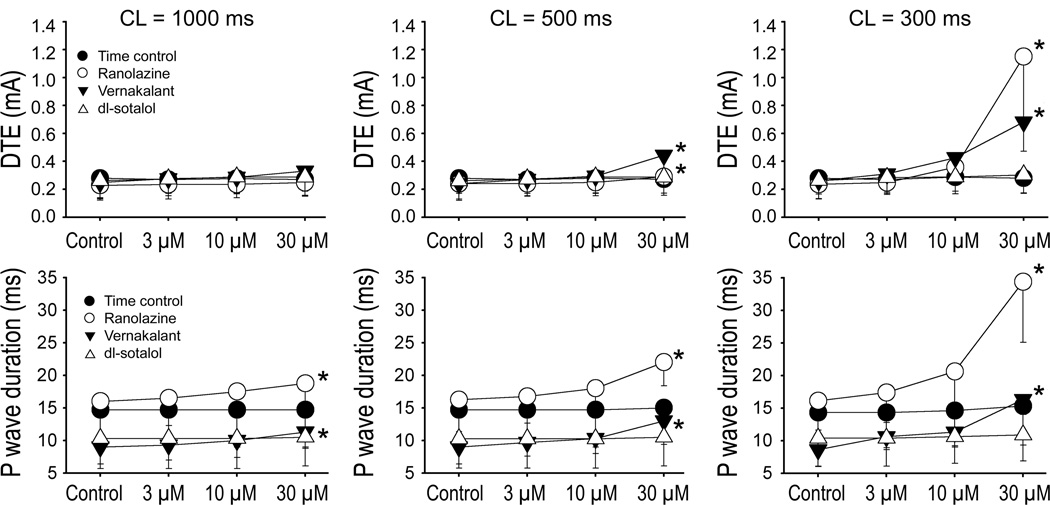

DTE was statistically significantly increased following exposure to 30 µM vernakalant or ranolazine (Fig. 7, upper panels). The extent of DTE increase was much greater at a CL of 300 vs. 500 ms with both agents. DTE was not affected by dl-sotalol at any concentration or frequency. The duration of the P wave was significantly increased by vernakalant and ranolazine at 30 µM at all pacing rates tested (Fig. 7, lower panels). The degree of conduction slowing by these test agents was clearly rate-dependent. No significant changes in P wave duration were seen with dl-sotalol.

Figure 7.

Rate- and concentration-dependent effects of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol on diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE) and on the duration of P wave in coronary-perfused left atrial preparations. Ranolazine and vernakalant significantly increased DTE and P wave duration at rapid activation rates. N=4–6 *- p<0.05 vs. respective control.

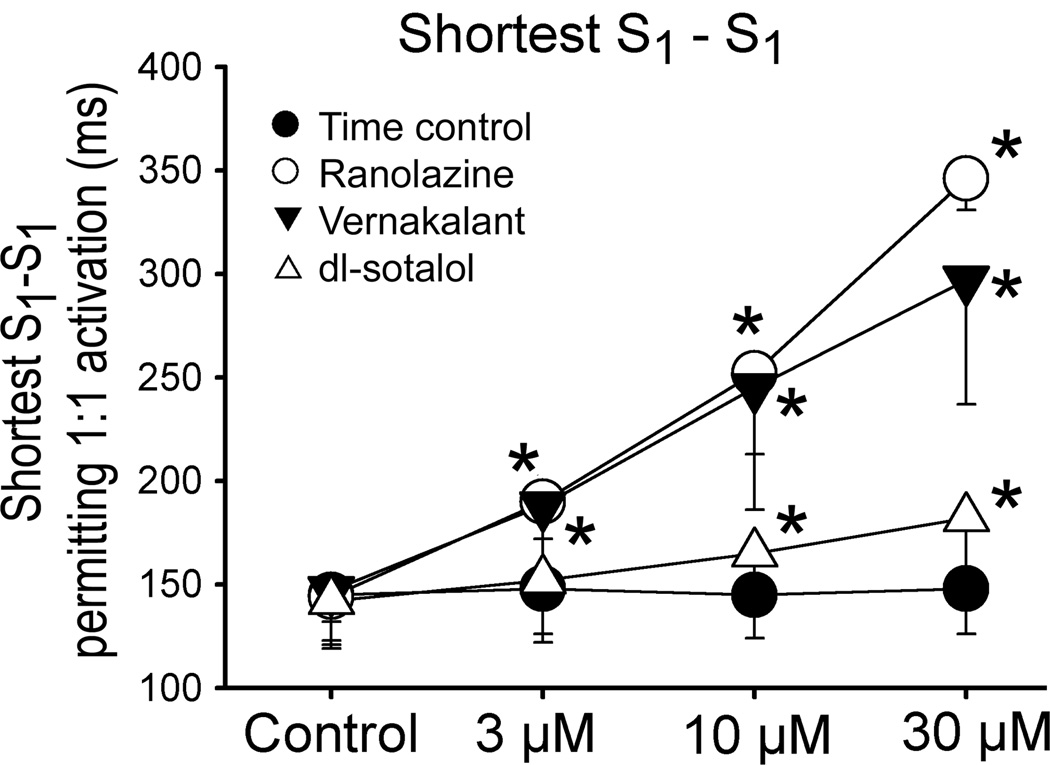

The shortest S1-S1 interval permitting 1:1 activation was significantly increased by vernakalant and ranolazine to a similar degree (Fig. 8). Dl-sotalol also prolonged the shortest S1-S1 interval permitting 1:1 activation, but to a much lesser extent than vernakalant or ranolazine.

Figure 8.

Effect of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol to prolong the shortest cycle length permitting 1:1 activation. N=4–6. *- p<0.05 vs. respective control.

Discussion

The results of this blinded study indicate that in healthy non-remodeled isolated canine left atria, the electrophysiological effects of vernakalant and ranolazine are characterized largely by frequency-dependent depression of sodium channel-mediated parameters and those of dl-sotalol by reverse rate-dependent prolongation of APD90 and thereby ERP. Vernakalant and ranolazine are shown to induce rate-dependent depression of Vmax, pointing to use-dependent reduction of peak INa leading to an increase in DTE, CT, and the briefest CL permitting 1:1 activation and development of PRR. Vernakalant, but not ranolazine or dl-sotalol, also produces an elevation of the atrial action potential plateau voltage, consistent with its effect to inhibit early repolarizing currents (i.e. IKur, Ito).

Electrophysiological effects of vernakalant, ranolazine, and dl-sotalol in left atria

Vernakalant inhibits IKur, Ito, peak and late INa, IKr, and IK(ACh).5 The results of our study suggest that the electrophysiological effects of vernakalant in isolated canine left atria preparations were due largely to block of the channel responsible for peak INa. Indeed, sodium channel-mediated electrophysiological parameters (such Vmax, PRR, DTE, CT, and the shortest S1-S1 CL permitting 1:1 activation) were altered by vernakalant in a rate-dependent fashion. ERP was prolonged principally by the development of PRR secondary to inhibition of INa.

A functional manifestation of block of IKur (and likely Ito) is a significant elevation of the action potential plateau voltage. Mathematical modeling indicates that “pure” block of IKur (80–90% of the current) should decrease the magnitude of phase 1 by about 25%.15, 16 The practical elimination of the atrial AP notch by vernakalant (at 10 and 30 µM; Fig. 1) is consistent with an additional significant block of Ito. Elevation of the plateau voltage by IKur blockers leads to an augmentation of IKr and IKs, which serves to abbreviate APD70–90 in normal atrial cells. A number of studies have shown an abbreviation of APD70–90 with IKur blockers in non-remodeled atria.11, 16, 17 Of note, in remodeled atria, which commonly exhibit a tri-angular AP morphology, IKur blockers cause a small prolongation in APD70–90.10, 16

Inhibition of late INa acts to reduce the height of the AP plateau and abbreviate APD. Vernakalant-induced late INa block appears to contribute relatively little to modulation of APD in our study. Vernakalant tends to prolong APD75–90 in atria (Fig. 1 and 2). This APD prolonging effect of vernakalant is likely due to the combined inhibition of multiple atrial K+ currents. Vernakalant-induced IKr block appears to counterbalance the APD90 abbreviating effect IKur and late INa inhibition.

The electrophysiological effects of ranolazine and dl-sotalol in the current study are consistent with previously published data and with the ion channel blocking profiles of these agents.13, 18 Indeed, the electrophysiological effects of ranolazine are readily explained by potent use-dependent block of the sodium channels (both peak and late INa) and reverse use-dependent block of IKr.13 Ranolazine produced little change in APD50 and a slight prolongation of APD90, presumably due to a combined effect of the drug to inhibit late INa and IKr (acting to abbreviate and prolong APD, respectively). Pure IKr block produces a prolongation of both APD50 and APD90 in atria.11 The principle effect of dl-sotalol was a reverse use-dependent prolongation of APD and ERP, consistent with its primary effect to inhibit IKr. At a concentration of 30 µM, dl-sotalol produced mild depression of INa–mediated parameters (Vmax, PRR, the shortest S1- S1). It is noteworthy that dl-sotalol has previously been demonstrated to inhibit INa in ventricular muscles and Purkinje fibers at high concentrations (>100 µM).19 While INa block with sotalol at therapeutic concentrations is not functionally detectable in the ventricles, it may be detectable in atria (considering the atrial selectivity of many INa blockers20). Intra-atrial conduction time in human atria has been reported to be increased by dl-sotalol in a use-dependent fashion,21 consistent with block of peak INa. The prolongation of APD with dl-sotalol, leading to a reduction in diastolic interval (DI), may have promoted block of INa at rapid activation rates in our study.

IKur, INa or multi ion channel block? What determines vernakalant-induced atrial-selective ERP prolongation?

ERP can be prolonged either by prolongation of APD70–90 (commonly due to block of atrial repolarizing potassium currents) or by development of PRR (secondary to block of peak INa). Preferential prolongation of the atrial ERP by vernakalant has been reported in a number of experimental and clinical studies.7–9 This atrial-selective effect of vernakalant has been commonly ascribed to the ability of vernakalant to inhibit potassium channels, particularly IKur, 7, 8, 22,23 a current present in atrial but not ventricular myocardium, as well as Ito and IKr.23, 24 In addition to inhibiting these potassium currents however, vernakalant blocks peak INa in a voltage and frequency-dependent manner,5 which may also cause atrial-selective ERP prolongation.13, 25 Atrial-selective ERP prolongation due to block of peak INa has been reported for a number of INa blockers (ranolazine, amiodarone, dronedarone, and AZD1305).13, 26–28 The effect of vernakalant on atrial APD has not been studied in great detail. However, preliminary data from APs recorded from patients with chronic AF showed that vernakalant prolongs both APD90 and ERP to a similar degree at a CL of 1000 ms (by 6 and 8%, respectively), suggesting a role of K+ channel inhibition in ERP prolongation in electrically remodeled AP.10 Only one pacing CL was tested in that study (i.e., 1000 ms).10 Considering the frequency-dependence of INa block with vernakalant,5 at faster pacing rates, which are more relevant in the setting of AF, ERP prolongation with vernakalant is expected to be greater (due to development of PRR, as in the present study; Fig. 3 and 4).

The present study is the first to measure the effect of vernakalant on both APD and ERP in isolated canine atria at several physiologically relevant pacing rates. The data obtained demonstrate that ERP prolongation induced by vernakalant in non-remodeled isolated canine atria is primarily due to PRR and that this effect is strongly rate-dependent, largely manifesting at 500 and 300, but not at 1000 ms CLs (Fig. 4). It appears that vernakalant is an atrial-selective sodium channel blocker and that its atrial-selective ERP prolongation, at least in normal tissue, is due in large part to block of INa, although indirect effects on INa resulting from changes in AP morphology cannot be excluded. Of note, vernakalant has rapid unbinding kinetics from the sodium channel, a key feature of all atrial-selective sodium channel blockers.25 Note that several prominent IKur blockers, along with vernakalant, have been to shown to inhibit peak INa (such as AZD7009, AZD1305, AVE0118).5, 27, 29, 30 ISQ1 and TAEA also slow conduction velocity in atria but not in ventricles in vivo,31 indicating that they block INa selectively in atria. These observations suggest that the atrial selectivity of most of these purported IKur blockers to prolong ERP may be mediated predominantly by their ability to inhibit INa.

Potassium or sodium channel block? Which is more important for vernakalant’s anti-AF action?

Several large clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of vernakalant to terminate recent onset AF.1–4 Prolongation of atrial ERP by vernakalant is thought to be one of the mechanisms involved in conversion of AF to normal sinus rhythm. Since vernakalant-induced ERP prolongation is primarily due to block of INa (at least in non-remodeled canine atria), block of peak INa would appear to be the principal contributor to the anti-AF actions of vernakalant.

Effects of the drugs in remodeled atria

AF is commonly associated with pathophysiologic conditions that lead to electrical and structural remodeling of the atria and the effects of pharmacological agents may be different in this setting. Remodeled atria typically display a short APD with a triangulated AP morphology. Atrial remodeling caused by heart failure and hypertension can be associated with unchanged or even prolonged APD/ERP.32–34 In these pathologies, atrial APD and ERP are likely to abbreviate secondary to AF. In a ventricular tachypacing-induced canine heart failure model, the electrophysiological effects of ranolazine in atria are well preserved (Burashnikov et al unpublished observation). In tissues isolated from patients with chronic AF, clinically relevant concentrations of vernakalant (10 µM) caused a statistically significant prolongation of APD and ERP without significantly reducing Vmax at a frequency of 1 Hz.10 Under the same experimental conditions, vernakalant caused no significant change in APD, ERP, or Vmax in atrial tissues isolated from patients in sinus rhythm.10 This suggests that the potassium channel blocking properties of vernakalant might play a larger role in the electrically remodeled atrium than in the non-remodeled one at normal or slow heart rates. This mechanism might contribute to the prevention of AF recurrence post conversion by vernakalant.35 At faster heart rates, it is expected that the parameters determined by the use-dependent INa blocking effect of vernakalant would become more manifest. Because IKur density is reduced following acceleration of pacing rate36 and is also reduced in atrial cells isolated from patients with persistent AF,37, 38 the IKur blocking effects of vernakalant are expected to be diminished at rapid activation rates in remodeled atria. Ultimately, as vernakalant blocks multiple potassium channel currents including IKur, Ito, IKr and IKAch as well as blocking INa,5 the electrophysiologic actions of vernakalant in remodeled atrium will reflect a balance of effects on all target currents present in this condition. Studies in an atrial pacing model of persistent AF in goat support the preserved activity of vernakalant in the electrically remodeled atrium.39 In the human remodeled atria with persistent AF and in atrial tachypacing remodeled goat atria, ERP prolonging ability of dl-sotalol is reduced.40, 41 Depending on the underlying causes of atrial remodeling (heart failure, hypertension, ischemia, age, AF, and their various combinations), electrophysiology and pharmacologic response of the remodeled atria can differ significantly depending on a number of factors including action potential duration and morphology, diastolic interval, resting membrane potential and rate of atrial activation.

Study limitations

The absence of autonomic and hormone influences, which can significantly modulate cardiac electrophysiology and pharmacological response, are among the limitations of our in vitro investigation. In addition, the results of our study were obtained in “healthy” atria, whereas AF normally occurs in electrically and structurally remodeled atria. Atrial remodeling can significantly modulate the pharmacological response.

Conclusions

This is the first full-length paper reporting the detailed effect of vernakalant on isolated canine atrial electrophysiology, with the vernakalant-induced changes in APD and ERP directly compared. The results of our study indicate that the rate-dependent effect of vernakalant and ranolazine to prolong refractoriness in non-remodeled isolated canine left atria is due largely to use-dependent block of peak INa. In contrast, sotalol showed reverse rate-dependent effects on ERP, consistent with its IKr blocking profile.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported by a grant from Merck & Co., grant HL47678 (CA) from NHLBI, and Masons of New York State and Florida.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Antzelevitch received research support from Merck & Co.; Dr. Lynch is an employee of Merck & Co.; Dr. Pourrier is an employee of Cardiome Pharma Corp.; and Dr Gibson is an employee of AAKVSL Pharma Consulting, LLC.

References

- 1.Roy D, Pratt CM, Torp-Pedersen C, Wyse DG, Toft E, Juul-Moller S, Nielsen T, Rasmussen SL, Stiell IG, Coutu B, Ip JH, Pritchett EL, Camm AJ. Vernakalant hydrochloride for rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation. A phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation. 2008;117:1518–1525. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowey PR, Dorian P, Mitchell LB, Pratt CM, Roy D, Schwartz PJ, Sadowski J, Sobczyk D, Bochenek A, Toft E. Vernakalant hydrochloride for the rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:652–659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.870204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiell IG, Roos JS, Kavanagh KM, Dickinson G. A multicenter, open-label study of vernakalant for the conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Am Heart J. 2010;159:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camm AJ, Capucci A, Hohnloser SH, Torp-Pedersen C, van Gelder IC, Mangal B, Beatch G. A randomized active-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of vernakalant to amiodarone in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:131–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedida D. Vernakalant (RSD1235): a novel, atrial-selective antifibrillatory agent. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:519–532. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orth PM, Hesketh JC, Mak CK, Yang Y, Lin S, Beatch GN, Ezrin AM, Fedida D. RSD1235 blocks late I(Na) and suppresses early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes induced by class III agents. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorian P, Pinter A, Mangat I, Korley V, Cvitkovic SS, Beatch GN. The effect of vernakalant (RSD1235), an investigational antiarrhythmic agent, on atrial electrophysiology in humans. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:35–40. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3180547553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bechard J, Gibson JK, Killingsworth CR, Wheeler JJ, Schneidkraut MJ, Huang J, Ideker RE, McAfee DA. Vernakalant selectively prolongs atrial refractoriness with no effect on ventricular refractoriness or defibrillation threshold in pigs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57:302–307. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182073c94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bechard J, Pourrier M. Atrial selective effects of intravenously administrated vernakalant in conscious beagle dog. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58:49–55. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821b8608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wettwer E, Bormann S, Christ T, Dobrev D, Pourrier M, Gibson KJ, Fedida D, Ravens U. Effects of the novel antiarrhythmic agent vernakalant (RSD1235) on human atrial action potentials in chronic atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(Suppl):400–400. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burashnikov A, Mannava S, Antzelevitch C. Transmembrane action potential heterogeneity in the canine isolated arterially-perfused atrium: effect of IKr and Ito/IKur block. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H2393–H2400. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01242.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sicouri S, Glass A, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in canine pulmonary vein sleeve preparations. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Zygmunt AC, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C. Atrium-selective sodium channel block as a strategy for suppression of atrial fibrillation: differences in sodium channel inactivation between atria and ventricles and the role of ranolazine. Circulation. 2007;116:1449–1457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bode F, Kilborn M, Karasik P, Franz MR. The repolarization-excitability relationship in the human right atrium is unaffected by cycle length, recording site and prior arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:920–925. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courtemanche M, Ramirez RJ, Nattel S. Ionic targets for drug therapy and atrial fibrillation-induced electrical remodeling: insights from a mathematical model. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:477–489. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wettwer E, Hala O, Christ T, Heubach JF, Dobrev D, Knaut M, Varro A, Ravens U. Role of IKur in controlling action potential shape and contractility in the human atrium: influence of chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;110:2299–2306. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145155.60288.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Can inhibition of IKur promote atrial fibrillation? Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whalley DW, Wendt DJ, Grant AO. Basic concepts in cellular cardiac electrophysiology: Part II: Block of ion channels by antiarrhythmic drugs. PACE. 1995;18:1686–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1995.tb06990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carmeliet E. Electrophysiologic and voltage clamp analysis of the effects of sotalol on isolated cardiac muscle and Purkinje fibers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;232:817–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. New development in atrial antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:139–148. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe H, Watanabe I, Nakai T, Oshikawa N, Kunimoto S, Masaki R, Kojima T, Saito S, Ozawa Y, Kanmatuse K. Frequency-dependent electrophysiological effects of flecainide, nifekalant and d,l-sotalol on the human atrium. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:1–6. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford JW, Milnes JT. New drugs targeting the cardiac ultra-rapid delayed-rectifier current (IKur): rationale, pharmacology and evidence for potential therapeutic value. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:105–120. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181719b0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedida D, Orth PM, Chen JY, Lin S, Plouvier B, Jung G, Ezrin AM, Beatch GN. The mechanism of atrial antiarrhythmic action of RSD1235. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1227–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.50028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang ZG, Fermini B, Nattel S. Sustained depolarization-induced outward current in human atrial myocytes: Evidence for a novel delayed rectifier K+ current similar to Kv1.5 cloned channel currents. Circ Res. 1993;73:1061–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Atrial-selective sodium channel block for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:233–249. doi: 10.1517/14728210902997939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Sicouri S, Ferreiro M, Carlsson L, Antzelevitch C. Atrial-selective effects of chronic amiodarone in the management of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burashnikov A, Zygmunt AC, Di Diego JM, Linhardt G, Carlsson L, Antzelevitch C. AZD1305 exerts atrial-predominant electrophysiological actions and is effective in suppressing atrial fibrillation and preventing its re-induction in the dog. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;56:80–90. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e0bc6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogdan R, Goegelein H, Ruetten H. Effect of dronedarone on Na(+), Ca (2+) and HCN channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;383:347–356. doi: 10.1007/s00210-011-0599-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlsson L, Chartier D, Nattel S. Characterization of the in vivo and in vitro electrophysiological effects of the novel antiarrhythmic agent AZD7009 in atrial and ventricular tissue of the dog. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:123–132. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000196242.04384.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burashnikov A, Barajas-Martinez H, Hu D, Nof E, Blazek J, Antzelevitch C. The atrial-selective potassium channel blocker AVE0118 prolongs effective refractory period in canine atria by inhibiting sodium channels. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:S98. (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regan CP, Kiss L, Stump GL, McIntyre CJ, Beshore DC, Liverton NJ, Dinsmore CJ, Lynch JJ., Jr Atrial antifibrillatory effects of structurally distinct IKur blockers 3-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-6-methoxy-2-methyl-4-phenylisoquinolin--1(2H)-one and 2-phenyl-1,1-dipyridin-3-yl-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-ethanol in dogs with underlying heart failure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:322–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li D, Melnyk P, Feng J, Wang Z, Petrecca K, Shrier A, Nattel S. Effects of experimental heart failure on atrial cellular and ionic electrophysiology. Circulation. 2000;101:2631–2638. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuberger HR, Schotten U, Verheule S, Eijsbouts S, Blaauw Y, van HA, Allessie M. Development of a substrate of atrial fibrillation during chronic atrioventricular block in the goat. Circulation. 2005;111:30–37. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151517.43137.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kistler PM, Sanders P, Dodic M, Spence SJ, Samuel CS, Zhao C, Charles JA, Edwards GA, Kalman JM. Atrial electrical and structural abnormalities in an ovine model of chronic blood pressure elevation after prenatal corticosteroid exposure: implications for development of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:3045–3056. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torp-Pedersen C, Raev DH, Dickinson G, Butterfield NN, Mangal B, Beatch GN. A randomized placebo-controlled study of vernakalant (oral) for the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence post-cardioversion. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:637–643. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng J, Xu D, Wang Z, Nattel S. Ultrarapid delayed rectifier current inactivation in human atrial myocytes: properties and consequences. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1717–H1725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, McCarthy PM, Trimmer JS, Nerbonne JM. Outward K+ current densities and Kv1.5 expression are reduced in chronic human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 1997;80:772–781. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christ T, Wettwer E, Voigt N, Hala O, Radicke S, Matschke K, Varro A, Dobrev D, Ravens U. Pathology-specific effects of the IKur/Ito/IK,ACh blocker AVE0118 on ion channels in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beatch GN, Helmes M, Blaauw Y, Allessie MA. Acute reversal of electrical remodeling and cardioversion of persistent AF by a novel atrial-selective antiarrhythmic drug, RSD1235, in the goat. Circ. 2004;110 III-163 (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duytschaever M, Blaauw Y, Allessie M. Consequences of atrial electrical remodeling for the anti-arrhythmic action of class IC and class III drugs. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tse HF, Lau CP. Electrophysiologic actions of dl-sotalol in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2150–2155. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]